Delay v. Carling Brewing Company Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Delay v. Carling Brewing Company Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1976. 3ccd1c90-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/52813b2d-1e02-4a4a-8ecf-5b4b1e028bfe/delay-v-carling-brewing-company-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

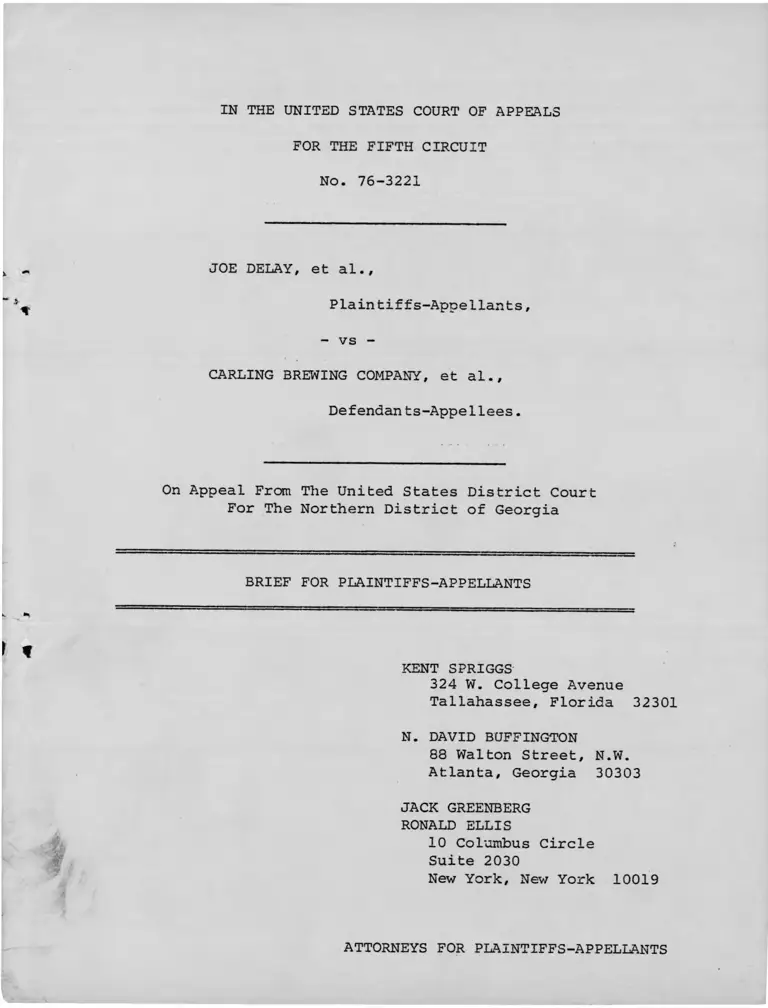

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 76-3221

JOE DELAY, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

- vs -

CARLING BREWING COMPANY, et al.,

Defendan ts-Appellees.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Northern District of Georgia

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

KENT SPRIGGS

324 W. College Avenue

Tallahassee, Florida 32301

N. DAVID BUFFINGTON

88 Walton Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

JACK GREENBERG

RONALD ELLIS

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 76-3221

JOE DELAY, et al.,

Plaint if f s-Appe Hants,

- vs -

CARLING BREWING COMPANY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

CIRTIFICATE REQUIRED BY FIFTH CIRCUIT

__________LOCAL RULE 13(a)___________

The undersigned, counsel of record for Plaintiffs-

Appellants, certifies that the following listed parties have

an interest in the outcome of this case. These representa

tions are made in order that Judges of this Court may

evaluate possible disqualification or recusal pursuant to

Local Rule 13(a).

1. Joe Delay and Walter Wilkins, both plaintiffs.

2. The class of black employees of Carling Brewing

Company who were employed at the company's Atlanta

Plant, whom the plaintiffs represent.

i

2

1

3. Carling Brewing Company, defendant.

4. Local 357, International Union of Brewery, Flour,

Cereal, Soft Drink and Distillery Workers of

America, AFL-CIO, now merged with the International

Brotherhood of Teamsters, Chauffeurs, Warehousemen

and Helpers of America, defendants.

ATTORNEY FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

V

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Certificate Required by Local Rule 13(a) ......... i

Table of Contents ................................ xii

Table of Authorities ............................. v

Statement of Issues Presented for Review ......... xi

r

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ................................. 1

STATEMENT OF FACTS ................................... 2

ARGUMENT ............................................. 4

THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN

GRANTING SUMMARY JUDGMENT

FOR DEFENDANTS BASED ON

SECTION 703(h) OF TITLE VII ......... 4

A. Neither the Language of

§703(h) nor the Legislative

History of Title VII Justif

ies the Interpretation of

the District Court .................. 5

A SENIORITY SYSTEM WHICH

' PERPETUATES THE EFFECTS OF

PRE-ACT DISCRIMINATION IS

I A LEGAL WRONG UNDER TITLE

VII ................................. 14

A. Seniority Rights are

Not Inviolable ...................... 14

B. Company Seniority, Like

Departmental Seniority, Can

Perpetuate Past Discrimina

tion and Thus be Illegal

Under Title VII ..................... 16

Page

iii

Page

C. Maintaining a Seniority System

Which Disadvantages Blacks Who Are

Identifiable Victims of Past

Racial Discrimination Is, Of Itself,

Present Discrimination As to Those

Individuals ...................... 20

D. Identifiable Victims of Pre-Act

Discrimination May Seek Redress

From a Seniority System Which Has

the Effect of Perpetuating That

Prior Discrimination ............. 23

E. The Closing of the Company's

Atlanta Plant, While Foreclosing

Certain Seniority Relief for

Plaintiffs, Has Eliminated

Equitable Objections Raised By Some

Courts ........................... 28

REGARDLESS OF THE RESULT OF

PLAINTIFFS' TITLE VII CLAIM, THE

DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN NOT GRANTING

RELIEF UNDER 42 U.S.C. §1981 ..... 30

CONCLUSION ...................................... 36

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

s

Cases:

Acha v. Beame, 531 F.2d 648 (2nd Cir. 1976) ___

Afro-American Patrolmens League v. Duck, 366

F. Supp..1095 (N.D. Ohio 1973), aff'd in

pertinent part, 503 F.2d 294 (6th Cir.

1974) ............................

22, 24, 25, 26

Page

22

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36

(1974) ..................................... 15, 31, 35

Allen v. City of Mobile, 331 F. Supp. 1134 (S.D.

Ala. 1971), aff'd per curiam, 466 F.2d 122

(5th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 412 U.S. 909

(1973) ..................................... 22

Alpha Portland Cement Co. v. Reese, 507 F.2d 607

'-(5th Cir. 1975) ...........................

Brady v. Bristol-Meyers Co., 459 F.2d 621 (8th

Cir. 1972) ...............................

Bridgeport Guardians, Inc. v. Members of Civil

Service Com'n, 497 F.2d 1113 (2nd Cir. 1974),

cert, denied, 421 U.S. 991 (1975) .......... 22

Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Co., 457 F.2d 1377

(4th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 982

(1972) ..................................... 30

Caldwell v. National Brewing Co., 443 F.2d 1044

(5th Cir. 1971), cert, denied, 405 U.S. 916

(1972) ..................................... 30

Chance v. Board of Examiners, 534 F.2d 993 (2nd

Cir. 1976) ................................. 24

Contractors Association of Eastern Pennsylvania

v. Secretary of Labor, 442 F.2d 159 (3rd Cir.

1971), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 854 (1971) ___ 33

v

Page

Dobbins v. Electrical Workers Local 212, 292

F. Supp. 413 (S.D. Ohio 1968), aff'd as later

modified, 472 F.2d 634 (6th Cir. 1973) ..... 21

EEOC v. Plumbers, Local Union No. 189, 311

F. Supp. 468 (S.D. Ohio 1970), vac1d on

other grounds, 438 F.2d 408 (6th Cir. 1971),

cert, denied 404 U.S. 832 (1971) ........... 21

Espinoza v. Farah Manufacturing Co., 414 U.S. 86

(1973) ..................................... 32

Evans v. United Air Lines, Inc., 534 F.2d 1247

(7th Cir. 1976), cert, granted, 45 U.S. L.W.

3321 (1976) ................................ 19

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., Inc.,

U.S. , 47 L.Ed 2d 444 (1976} ..........

2, 4, 6, 8, 14,

25, 29, 30

Ford Motor Co. v. Huffman, 345 U.S. 330

(1953) ..................................... 14, 15

Gresham v. Chambers, 501 F.2d 687 (2nd Cir.

(1974) ..................................... 34

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424

(1971) .....................................

A

7

Guerra v. Manchester Terminal Co., 498 F.2d

i 641 (5th Cir. 1974) ........................ 32

Harper v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore,

359 F. Supp 1187 (D. Md. 1973), aff'd sub

nom. Harper v. Kloster, 489 F.2d 1134 (4th

Cir. 1973) ................................. 22

Head v. Timken Roller Bearing Co., 486 F.2d 870

(6th Cir. 1973) ............................ 16, 30

Humphrey v. Moore, 375 U.S. 335 (1964) ........ 14

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421 U.S.

454 (1975) ................................. 30, 31

vi

Page

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409

(1968) 34

Local 189, United Paperxnakers and Paperworkers v. 7, 8, 13, 14,

United States, 416 F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969) 15, 16, 19,

cert, denied, 397 U.S. 919 (1970) .......... 21, 30

Loy v. City of Cleveland, 8FEP Cases 614 (N.D.

Ohio 1974) 22

Macklin v. Spector Freight Systems, Inc., 478

F .2d 979 (D.C. Cir. 1973) 34

Meadows v. Ford Motor Co., 510 F.2d 939 (6th Cir.

1975) , cert, denied (1976) ................. 2, 8, 29

Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535 (1974) 33

Nance v. Union Carbide Corporation, Consumer 21, 18

Products Division, 540 F.2d 718 (4th Cir.

1976) ......................................

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400

(1968) 15

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d

211 (5th Cir. 1974) 30

Posadas v. National City Bank, 296 U.S. 497

(1936) 33

Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 279 F. Supp. 505 7, 13, 15,

(E.D. Va. 1968) ............................ 19, 21

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791 (4th

Cir. 1971), cert, dismissed, 404 U.S. 1006

(1971) 13, 16

Rowe v. General Motors Corp., 457 F.2d 348 (5th

Cir. 1972) ................................. 7, 22

Sanders v. Dobbs Houses, Inc., 431 F.2d 1097

(5th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 401 U.S. 948

(1971) ..................................... 30, 34

vii

Page

«

i

Schaeffer v. Tannian, 394 F. Supp. 1136 (E.D.

Mich. 1975) ...........................

Silver v. New York Stock Exchange, 373 U.S. 341

(1963) ..................

Sullivan v. Little Hunting Park, Inc., 396 U.S.

229 (1969) ................................

Tillman v. Wheaton-Haven Rec. Ass'n, 410 U.S.

431 (1973) ................................

United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446 F.2d

652 (2nd Cir. 1971) .......................

United States v. Chesapeake & Ohio R. Co., 471

F.2d 582 (4th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 411

U.S. 939 (1973) ...........................

United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d 906

(5th Cir. 1973) ...........................

United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co., 451

F.2d 418 (5th Cir. 1971), cert, denied, 406

U.S. 906 (1972) ...........................

United States v. N.L. Industries, Inc., 479 F.2d

354 (8th Cir. 1973) ....................... .

United States v. Sheet Metal Workers, Local 36,

416 F.2d 123 (8th Cir. 1969) ...............

Vogler v. McCarty, Inc., 451 F.2d 1236 (5th Cir.

1971) ......................................

Washington v. Davis, _____U.S._____ 48 L.Ed 2d

597 (1976) .................................

Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works of International

Harvester Co., 427 F.2d 476 (7th Cir. 1970),

cert, denied, 400 U.S. 911 (1970) ..........

27

33

34

35

13, 20, 22

16

17

16, 19

16

21

15

32

34

viii

Page

Watkins v. Scott Paper Co., 530 F.2d 1159 (5th

Cir. 1976), cert, denied, _____U.S._____

(1976) ..................................... 5, 23, 24

Watkins v. United Steel Workers of America, Local

No. 2369, 516 F.2d 41 (5th Cir. 1975) ...... 19

Young v. International Telephone & Telegraph Co.,

438 F.2d 757 (3rd Cir. 1971) ............... 34

i

Statutes:

42 U.S.C. §1981 (Civil Rights Act of 1886) ..... 1, 30, 31, 32, 33

42 U.S.C. §1982 ............................... 34> 35

42 U.S.C. §§2000a et. seq. (Title II, Civil

Rights Act of 1964) ]_q

42 U.S.C. §2000a (e) 35

42 U.S.C. §§2000d et. seq. (Title VI, Civil

Rights Act of 1964) 10

42 U.S.C. §§2000e et. seq. (Title VII, Civil

•̂■i-Û ts Act of 1964) ......................... passim

42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(a) (Title VII, §703 (a) ..... 7, 15

t 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(c) (Title VII, §703 (c) ..... 7

42 U.S.C. §2000e-2 (h) (Title VII, §703 (h) ..... passim

42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(j) (Title VII, §703 (j) ..... 33

42 U.S.C. §§3601 et. seq. (Civil Rights Act of

(1968) 34

xx

Legislative Materials: paqe

110 Cong. Rec. 2726 (1964) 12

110 Cong. Rec. 2727 (1964) 12

110 Cong. Rec. 2728 (1964) 12

110 Cong. Rec. 7206 (1964) (Interpretative

Memorandum prepared by Department of

Justice .................................... Q> i3

110 Cong. Rec. 7212 (1964) (Clark-Case

Interpretative Memorandum .................. 8, 9, 13

110 Cong. Rec. 7215 (1964) (Clark-Kirksen

Responses) ................................. g/ 13

110 Cong. Rec. 11,930 (1964) 10

110 Cong. Rec. 12,723 (1964) 11

110 Cong. Rec. 12,813 (1964) 10

110 Cong. Rec. 13,650 (1964) 31

110 Cong. Rec. 14,511 (1964) 11

110 Cong. Rec. 15,896 (1964) 11

110 Cong. Rec. 15,998 (1964) 11

110 Cong. Rec. 16,002 (1964) 11

H.R. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1963) ..................................... 12

H.R. Rep. No. 92-238 (1971) ................... 31

S. Rep. No. 92-415 (1971) ..................... 31

Authority:

Cooper and Sobol, Seniority and Testing Under Fair

Employment Laws: A General Approach to

Objective Criteria of Hiring and Promotion, 82

HARV.L.REV. 1598 (1969) ..................... 10, 20, 28

x

STATEMENT OF ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

1. Whether the district court erred in dismissing

plaintiffs' Title VII claim.

2. Whether the district court erred in not granting

plaintiffs relief under 42 U.S.C. §1981.

xi

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This is an action brought in the United States District

Court, Northern District of Georgia, by Joe Delay ("Delay") and

Walter Wilkins ( Wilkins") as a class action to enforce the

provisions of 42 U.S.C. §1981 and Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §2000e et seg., against Carling Brewing

Company ("Carling") and Local 357, International Union of United

Brewery, Flour, Cereal, Soft Drink, and Distillery Workers of

America ("Local 357"). In their complaint, filed September 21,

1973, Delay and Wilkins sought injunctive and other appropriate

relief for themselves and the class. They alleged that Carling

discriminated against black workers in that layoffs and recalls

were determined by a collectively-bargained plant seniority sys

tem based on date of hire; thus, because blacks were

categorically excluded from employment by Carling prior to 1963,

a disproportionate number of blacks were laid off each year

because of the substantial seasonal fluctuation in Carling's

work force. (R. 4-7)*Carling filed its answer on November 30,

1973. (R. 26-30) Local 357's parent international union merged

with the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, et al.

("Teamsters"); District Judge Newell Edenfield allowed counsel

for Local 357 to withdraw because the Teamsters did not desire

to use the same counsel. (R. 32-34) After answering interroga

tories served upon it by plaintiffs (Interrogatories: R. 11-16;

* Citations to Record are in this form.

Answers and Attachments: R. 35-352), Carling moved for summary

judgment on February 15, 1974. (R. 353) On June 25, 1974,

Judge Edenfield entered an order denying Carling's motion for

summary judgment. (R. 551-554) The order was based primarily

on Watkins v. United Steel Workers of America, Local 2369. 369

F. Supp. 1221 (E.D. La. 1974). (R. 553, 554) On February 25,

1975, Carling moved for reconsideration of its previous motion.

(R. 555) On March 12, 1975, Judge Edenfield entered an order

staying further proceedings pending the Fifth Circuit's decision

in Watkins, supra. (R. 566-567) On July 31, 1975, following

the Fifth Circuit decision, Judge Edenfield entered an order dis

solving the stay and inviting the parties to file new briefs in

light of the decision. (R. 570-571) Following the filing of

the called-for briefs, on December 22, 1975, Judge Edenfield

entered an order staying further proceedings pending the Supreme

Court's decision in Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.. 495

F.2d 398 (5th Cir. 1974), cert, granted. 420 U.S. 989 (1975).

(R. 599-602) On April 7, 1976, plaintiffs filed a motion to dis

solve the stay because the Supreme Court had decided Bowman.

supra. (R. 603) On July 30, 1976, Judge Edenfield entered an

order granting Carling's motion for summary judgment. (R. 616-

621) It is from this order that plaintiffs have appealed.

(R. 623)

STATEMENT OF FACTS

Carling engaged in a systematically discriminatory program

2

of refusing to hire blacks until approximately 1963. (R. 551)

Delay sought employment at Carling in 1960. (R. 519) Wilkins

sought employment at Carling in 1963. (R. 548) During Congress

ional deliberation on the Civil Rights Act of 1964, but prior to

its enactment (July 2, 1964) and its effective date (July 2,

1965), Delay and Wilkins were hired by Carling. (R. 521,549,

respectively) The collective bargaining agreement between

Carling and Local 357 provided for layoffs and recalls on the

basis of a plant-wide seniority system. (R. 552) Due to the

seasonal nature of the brewery business, many of Carling's employ

ees were laid off for up to six months of each year. (R. 520,549,

552) Because of the late date at which Carling began to hire

blacks, the practical result of the last hired-first fired

seniority system was that all black employees were laid off four

to six months each year. (R. 552) This caused not only a large

direct economic effect on the black workers, but also resulted in

the black workers being ineligible for pension and health

benefits and vacation leave. (R. 549-552) Delay filed a charge

of discrimination with the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission on April 22, 1969. (R. 37) The financial effect of

the layoffs was so great that Delay was forced to resign in

July, 1969. (R. 520) Carling decided to close its Atlanta

brewery, and, as it curtailed its operations, it terminated all

of its remaining black employees in 1972. (R. 549) Carling

closed its brewery in 1974. (R. 563) Delay received his right-to-

sue letter dated July 11, 1973 from the Equal Employment Opportunity-

Commission (R. 8), and, together with Wilkins, filed the instant

action on September 21, 1973 (R. 4).

3

ARGUMENT

THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN

GRANTING SUMMARY JUDGMENT

FOR THE DEFENDANTS BASED ON

SECTION 703 (h) OF TITLE VII

The district court's order in the instant case resulted

from an improper extention of the Supreme Court's decision

i-n Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co,. _____ U.S. ,

47 L.Ed 2d 444 (1976). In Franks, the Court stated clearly

in the beginning of its opinion what that case was concerned

with:

This case presents the question

whether identifiable applicants

who were denied employment

because of race after the

effective date and in violation

of Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§2000e

et seq. [42 U.S.C.S. §§2000e et

seq.], may be awarded seniority

status retroactive to the dates

of their employment applications

(footnote omitted). 47 L.Ed 2d

at 453.

It is thus quite clear that Franks was not this case. The

Court was faced with denials of employment after the

effective date of Title VII. Here the denials occurred prior

to the effective date of Title VII. Yet, the district court

presumed to extract from that decision a controlling

principle for a situation which was not before the Court and

4

which the Court had no need to decide.

The fallacy in the district court's approach is self-

evident. The court began by stating that the Supreme Court

noted a difference between pre-Title VII and post-Title VII

1/

discrimination in hiring. From there, it concluded that,

while the latter formed a basis for relief, the former did

not. There, however, is no logical nexus between the

premise (different situation) and the conclusion (opposite

result). Indeed this Court has declined to make a similar

inference. Watkins v. United Steel Workers of America, Local

No.2369, 516 F.2d 41 (5th Cir. 1975). As the discussion,

infra, makes clear, it is the similarity between the two

situations, and not the difference, which is determinative

of the result.

A. Neither the Language of §703(h) nor the Legislative

History of Title VII Justifies the Interpretation of

the District Court.

The district court interpreted Section 703(h) as grant

ing an exemption for plant seniority:

If §703(h) means anything at all,

it must mean that plant seniority

rights acquired prior to the

passage of the Act are not to be

,l/"This court agrees with the defendant that the Supreme

Court opinion in Franks makes a distinction between pre-

and post-Act discrimination as it relates to vested

seniority rights." (R. 620)

_ 5 _

divested in order to correct the

effects of unfortunate, but not

illegal, past discrimination.

(R. 620).

The court purported to draw support from the legislative

history of Title VII. An analysis of section 703(h) itself

and Title VII history in general, however, does not sustain

2/

this contention by the district court.

Section 703(h), 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(h), provides in

pertinent part:

Notwithstanding any other provision

of this title, it shall not be

unlawful employment practice for an

employer to apply different stand

ards of compensation, or different

terms, conditions, or privileges of

employment pursuant to a bona fide

seniority or merit system. . . .

2/ Cf.. Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., supra, where

the Supreme Court said about §703(h):

[I]t is apparent that the thrust of

the section is directed toward

defining what is and what is not an

illegal discriminatory practice in

instances in which the post-Act

operation of a seniority system is

challenged as perpetuating the

effects of discrimination occurring

prior to the effective date of the

Act. 47 L.Ed 2d at 460.

No exemption for plant seniority is noted. That, of course,

would presume to answer the question of "what is not an

illegal discriminatory practice," namely, the use of plant

seniority.

6

Stated simply the clause means that an employer may utilize

a "bona fide seniority or merit system" without being

guilty of an unlawful employment practice. Neither this

section nor any other part of Title VII defines what is

meant by the phrase "bona fide" seniority system. The

courts, however, have generally agreed that "one characteris

tic of a bona fide seniority system must be lack of discrim

ination." Quarles v. Philip Morris. Inc.. 279 F.Supp. 505,

517 (E.D. Va. 1968); Local 189. United Papermaker & Paper-

workers v. United States.416 F.2d 980, 987 (5th Cir. 1969),

cert, denied. 397 U.S. 919 (1970).

This interpretation of §733 (h) is consistent with the

broad prohibitory language of §§703 (a), (c), 42 U.S.C.

§§2000e-2(a), (c). These provisions generally define unlaw

ful employment practices by employers and unions#

respectively. By their terms they would appear to prohibit

any discriminatory employment practice unless it is

3/

specifically authorized elsewhere.

3/ See, e«g., Local 189, United Papermaker^and Paperworkers

v. United States, 416 F.2d 980; (5th Cir. 1969), cert.

denied, 397 U.S. 919 (1970) (hereinafter "Local 189") Rowe

v. General Motors Corp.. 457 F.2d 348, (5th Cir. 1972);

Griggs v. Duke Power Co.. 401 U.S. 424 (1971).

7

The legislative history of Title VII provides no basis

for altering this construction of §703(h), i.e. that a dis

criminatory seniority system is not protected. See Franks

v . Bowman Transportation Co.. supra. At best the history

of the title is confusing and contradictory as regards

seniority rights. Much of the controversy centers around

several documents inserted into the Congressional record

by Senator Clark, the floor manager of the equal employment

title. The three documents are an Interpretative Memorandum

PreP^red by the Department of Justice, 110 Cong. Rec. 7206-

07, "Clark-Case Interpretative Memorandum," 110 Cong. Rec.

4/ Local 189, supra (legislative history is "singularly uninstructive on seniority rights").

5/ The Department of Justice Memorandum states in pertinent part:

Title VII would have no effect on seniority rights existing at the time it takes effect,

if/ for example, a collective bargaining con

tract provides that in the event of layoffs,

those who were hired last must be laid off

first, such a provision would not be affected

in the least by Title VII. This would be

true even in the case where owing to dis

crimination prior to the effective date of

the title, white workers had more seniority

than Negores. Title VII is directed at

discrimination based on race, color, religion,

sex or national origin. It is perfectly clear

that when a worker is laid off or denied a

chance for promotion because under established

seniority rules he is low man on the totem

pole he is not being discriminated against

because of his race. 110 Cong. Rec. 7207.

8

7212-15, and a set of prepared answers by Senator Clark to6/

questions suggested by Senator Dirksen, 110 Cong. Rec.1/7215-17.

6/ The "Clark-Case Memorandum," states that:

Title VII would have no effect on established

seniority rights. Its effect is prospective

and not retrospective. Thus, for example,

if a business has been discriminating in the

past and as a result has an all-white working

force, when the title comes into effect the

employer's obligation would be simply to

fill future vacancies on a nondiscriminatory

basis. He would not be obliged — or indeed,

permitted — to fire whites in order to hire

Negores, or to prefer Negores for future

vacancies, or, once Negroes are hired to

give them special seniority rights at the

expense of the white workers hired earlier.

(However, where waiting lists for employment or training are, prior to the effective

date of the title, maintained on a discrimina

tory basis, the use of such lists after the

title takes effect may be held an unlawful

subterfuge to accomplish discrimination.)

110 Cong. Rec. 7213.

7/ Two of the prepared responses are pertinent to the ques

tion here.

Question. Would the same situation prevail in respect to

promotions when that management function is governed

by a labor contract calling for promotions on the

basis of seniority? What of dismissals? Normally,

labor contracts call for 'last hired, first fired.'

If the last hired are Negores, is the employer dis

criminating if his contract requires that they be

first fired and the remaining employees are white?

Answer. Seniority rights are in no way affected

by the bill. If under a 'last hired, first fired'

agreement a Negro happens to be the 'last hired,' he

can still be 'first fired' as long as it is done

because of his status as 'last hired' and not because

of his race. 110 Cong. Rec. 7217.

* * *

_ 9

There are numerous reasons why these statements do not

properly reflect the meaning of Title VII as enacted.^/

The most critical defect in relying on these statements is

that they were made before the present Title VII was drafted

and more particularly, the specific language of Section 703(h),

relating to seniority, was drafted. Some weeks after these

statements were inserted in the Congressional Record, a sub

stitute "Dirksen—Mansfield" bill, authoredtya bipartisan

leadership group, was introduced on May 26, 1964 as a sub

stitute for the original bill. (110 Cong. Rec. 11930-36).

This substitute bill replaced the Clark bill in its entirety

2/and modified it substantially. It was this substitute,

containing §703(h), 110 Cong. Rec. 12,813 (1964), which was

"Question. If an employer is directed to abolish

his employment list because of seniority discrimination,

what happens to seniority?

Answer: The bill is not retroactive, and it will

not require an employer to change existing seriority lists."

8/ See Cooper and Sobol, Seniority and Testing Under Fair

Employment Laws: A general Approach to Objective Criteria of

Hiring and Promotion. 82 Harv. L. Rev. 1598, 1611-1614.

9/ The Senatorial deadlock that produced the substitute was

not to any significant extent over seniority. The proscrip

tions on employment discrimination contained in the Title VII

bill were merely one part of an historic omnibus bill which

also had controversial titles prohibiting, inter alia, dis

crimination in public accommodations (Title II, see 42 U.S.C.

§§2000a et seq.) and in federally-assisted programs including

public and private schools (Title VI, see 42 U.S.C. §§2000d

et seq.). Even limiting the analysis to Title VII provisions,

the critical issue was not over seniority but whether EEOC

should have any enforcement powers and if so of what nature

("cease-and-desist" or right to sue in federal court). See,

e.g., 110 Cong. Rec. 12,721-22 (1964) (remarks of Senator Humphrey).

10

subsequently enacted. 110 Cong. Rec. 14,511 (1964). The

statements introduced by Senator Clark were thus interpretive

of a bill that did not pass and not of Title VII or of §703(h)

as enacted. It is therefore appropriate to rely on the

specific language of §703(h) rather than on these earlier

legislative statements.

In explaining the addition of §703(h), Senator Humphrey

commented that "[t]he change does not narrow application of

the title, but merely clarifies its present intent and effect,"

110 cong. Rec. 12,723 (1964). No further explanation of the

new section was made in the Senate. In the House, Rep. Celler,

the bill's House Manager, explained the changes made by the

substitute bill. He noted as a significant modification the

provision of §703(h) permitting non-discriminatory ability

10/tests.— 110 Cong. Rec. 15,896. He made no mention of its

"bona fide seniority system" language. id. This failure to

note the seniority language as significant has added import

when the House's previous concern over the effects on seniority

is considered. A dissenting minority of the House Judiciary

10/ After final passage of Title VII, Rep. McCullough, "who

had much to do with the passage and also the preparation of

the civil rights bill," 110 Cong. Rec. 15,998 (1964) (remarks

of Sen. Dirksen), prepared a comparative analysis of the

original House-passed bill and the final Senate version. That

analysis notes that the House version lacked any §703(h) pro

vision, but describes the Senate-added section solely as

authorizing the use of professionally developed ability tests, 110 Cong. Rec. 16,002 (1964).

11

Committee, which reported the bill out with favorable recom

mendation, argued that the bill would destroy all seniority

l1/systems.— The bill's proponents did not refute these

statements. An amendment to exempt from Title VII's pros

cription all employment practices based on a seniority

system was defeated on the House Floor. 110 Cong. Rec.

2727-2728 (1964).

To ascribe to §703(h) an exemption for seniority systems

would be to accept the premise that House leaders, who had

specifically rejected such an exemption, did not consider

such a change significant and therefore found no reason to

comment thereon.

The viability of the Clark materials is further suspect

because, taken literally, they would immunize all established

11/ The minority protested that,

If the proposed legislation is enacted, the

President of the United States and his appointees -

particularly the Attorney General - would be granted

the power to seriously impair . . . the seniority

rights of employees in corporate and other employment

[and] the seniority rights of labor union members

within their locals and in their apprenticeship

program.

The provisions of this act grant the power to

destroy union seniority . . . . with the full statu

tory powers granted by this bill, the extent of

actions which would be taken to destroy the seniority

system is unknown and unknowable. H. Rep. No. 914,

88th Cong. 1st Sess. 64-66, 71-72 (emphasis supplied).

See also, 110 Cong. Rec. 2726 (1964) (remarks of

Rep. Dodwy).

12

seniority rights. Courts have unanimously rejected this notion

13/as inconsistent with the true Congressional purpose. Any

interpretation which shields a system having discriminatory

effects is similarly at odds with Congressional intent.

The construction given §703(h) by the district court

provides such a shield, for it would immunize a seniority sys

tem, no matter how discriminatory its effect unless there is

12/

12/ See, e,g., the following statements:

"Title VII would have no effect on seniority

rights existing at the time it takes effect."

Department of Justice Interpretative Memorandum,

110 Cong. Rec. 7207 (1964).

"Title VII would have no effect on establish

ed seniority rights. Its effect is prospective

and not retrospective." Clark-Case Interpretative

Memorandum, 110 Cong. Rec. 7213 (1964).

"Answer: The bill is not retroactive, and it

will not require an employer to change existing sen

iority lists." Clark-Dirksen responses, 110 Cong.

Rec. 7217 (1964).

12/ See, e.q., Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc. 279 F.

Supp. 505, 515-8 (E.D. Va. 1968) ("It is also

apparent that Congress did not intend to freeze an

entire generation of Negro employees into discrim

inatory patterns that existed before the Act");

Local 189, United Papermakers and Paperworkers v.

United States, supra. 416 F.2d at 988, 966; Robinson

v. LoriHard Corp.. 444 F.2d 791 (4th Cir. 1971);

cert, dismissed , 404 U.S. 1006 (1971); United States

v. Bethlehem Steel Corp.. 446 F.2d 652 (2nd Cir. 1971).

13

some separate post-Act discriminatory practice. The court

thus felt that it could not modify vested seniority rights

unless there was some "underlying legal wrong" occurring after

the Act. This interpretation ignores the fact that a

seniority system, as applied, can be impermissibly discriminatory

A SENIORITY SYSTEM WHICH PERPETUATES THE

EFFECTS OF PRE-ACT DISCRIMINATION IS A

LEGAL WRONG UNDER TITLE VII_____________

A. Seniority Rights are not Inviolable.

Seniority has developed into crucial determinant of employ

ment opportunities in American industry. Indeed, seniority

serves a salutory purpose in employer-employee relationship.

Its objectivity and ease of application make it a particularly

appealing instrument for making decisions. The security it

affords causes courts to pause in addressing possible changes,

15/

changes that might upset the expectations of employees. It must

be remembered, however, that seniority rights are not sacrosanct.

They are not vested property rights, but may be altered in

appropriate circumstances. Humphrey v. Moore. 375 U.S. 335, 345-

50 (1954); Ford Motor Co. v. Huffman. 345 U.S. 330, 337-39 (1953)

14/

14/ This construction in effect means that the seniority system

cannot of itself by discriminatory. This reasoning, of course,

would have to be based on a distinction between plant seniority

and job, or departmental, seniority since the latter have been

found to be discriminatory because of their perpetuating effect.

Local 189, supra. This dictinction is logically unsupportable.

See infra paces 16 et seq.

15/ See generally Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., supra.

14

Seniority rights are particularly susceptible when strict

adherence would contravene a strong public policy.— ^

Congress has determined that equality in employment

is an important public policy and the eradication of dis

crimination should be given the "highest priority."

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver, 415 U.S. 36 (1974); Newman v.

Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S. 400 (1968). Consistent

with this directive, courts have determined that seniority

schemes may not stand when the important rights guaranteed by

Title VII are thereby denied:

Adequate protection of Negro rights under

Title VII may necessitate, as in the

instant case, some adjustment of the rights

of white employees. The court must be free

to deal equitably with conflicting interests

of white employees in order to shape remedies

that will most effectively protect and re

dress the rights of the Negro victims of

discrimination. Vogler v. McCarty, Inc.,

451 F.2d 1236 (5th Cir. 1971)

The seniority scheme is not immune from modification because

17,/it was established before the Act. Local 189, supra.

16/ See e.g., Ford Motor Co. v. Huffman, supra. In this

case, a collective bargaining agreement gave seniority credit

to veterans for periods spent in military service prior to

initial employment.

17/ "It is also apparent that Congress did not intend to

freeze an entire generation of Negro employees into discrimin

atory-patterns that existed before the act." Quarles v.

Philip Morris, Inc., 279 F.Supp. 505, 517 (E.D. Va. 1968)

15

The line of cases dealing with departmental or job

seniority has adhered to this interpretation. The fact that

the departmental scheme had been established prior to Title

VII did not shield such systems from review.

18/

B. Company Seniority, Like Departmental Seniority,

Can Perpetuate Past Discrimination and Thus be

Illegal Under Title VII.

It is extremely important that the import of the

"departmental seniority cases" be clearly understood. These

decisions substituting plant or tool employment seniority

for job or departmental seniority were not based on the notion

that plant seniority is per se valid. Rather, they are

grounded in the realization that, on the facts of those cases,

job or departmental seniority perpetuated the effects of the

past discrimination while plant seniority did not:

As we have indicated, we do not hold that

'mill seniority' is per se required under

Title VII. But we do hold that, where, as

here, 'job seniority' operates to continue

the effects of past discrimination, it

must be replaced by some other, non-dis-

criminatory, system, and that mill seniority

is an appropriate system in this case.

(emphasis added) United States v. Local 189,

United Papermakers & Paperworkers, 282 F.

Supp. 39, 45 (E.D. La. 1968), aff'd, 416

F.2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied

397 U.S. 919 (1970)

18/ See e.g., Local 189, United Papermakers & Paperworkers v.

United States, supra; United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co.,

451 F.2d 418 (5th Cir. 1971); Robinson v. Lorillard Corp~ 444

F.2d 791 (4th Cir. 1971) cert, dismissed 404 U.S. 1006 (1971);

United States v, Chesapeake & Ohio R. Co., 471 F.2d 582 (4th

Cir. 1973), cert. denied 411 U.S. 939 (1973); United States v.

N. L. Industries, Inc., 479 F.2d 354 8th Cir. 1973); Head v.

Timken Roller Bearing Co., 486 F.2d 870 (6th Cir. 1973).

16

In the departmental seniority cases," the companies hired

blacks prior to the Act, but assigned them to segregated

departments, or jobs. The use of department seniority as the

determinant after the Act disadvantaged blacks who had no

seniority in the better paying white departments - and thus

would be relegated to the bottom of the line. Since, however,

both blacks and whites had generally entered the plant on a

non-discriminatory basis (i.e. discrimination in hiring was

not the barrier), plant seniority served as a neutral standard

for work allocation.

The reasoning of these cases is compelling. It would

be unfair to blacks, and of course illegal, to allocate work

on the basis of length in service on jobs from which blacks

had been excluded. The logic applies a fortiori to the totally

segregated plant. In such a case, the black worker has not

been allowed to accumulate any seniority, plant or depart

mental. The use of plant seniority avails him not. Some

other, non-discriminatory employment practice must be employed

or the seniority system somehow altered. As this Court stated

in United States v. Georgia Power Co., 474 F.2d 906 (5th Cir.

1973) :

If the present seniority system in fact

operates to lock in the effects of past

discrimination, it is subject to judicial alteration under Title VII.

There is no reason to exempt a plant seniority system from

this rule. The Fourth Circuit agrees with the foregoing

- 17

reasoning. Nance v. Union Carbide Corp., Consumer Products

Division, 540 F.2d 718 (1976). In Nance, an employee's

"company service" was his period of employment less layoffs.

The female plaintiff did not have enough "company service"

to withstand a layoff in 1970. The plaintiff alleged that

the layoff "resulted from an improper deduction in her

company service record" because of "sex-discriminatory lay

offs in the pre-Act period of her employment." 540 F.2d at

19/728.— xn holding that the plaintiff was entitled to have

her "company service status adjusted" to remove the adverse

effects of any pre-Act discriminatory layoffs, the Court

stated:

Such a system obviously gave the male employee

a preferred opportunity to protect his 'company

service' over the female employee. This more

extensive opportunity in bidding for vacancies

during layoffs on the part of male employees

was a discrimination against female employees

and because that discrimination was carried over

in the operation of the post-Act Seniority system

it tainted such post-Act system. (Emphasis added).

540 F.2d at 729.

The Court thus recognized that the seniority system in ques

tion was not bona fide since it had its genesis in racial

19/ "Plaintiff's claim is that the defendant, by following

a discriminatory practice of limiting female employment to

certain job classifications, narrowed the opportunity of its

female employees to bid on an equal basis with male employees

for job vacancies in the plant, thereby causing a female em

ployee to suffer generally more layoff time than a comparably

qualified male employee." Id. at 728.

-18-

[or sex] discrimination. — ^ 540 F.2d at 729; Quarles v

Philip Morris, Inc., supra.

It must be remembered that seniority, be it depart

mental or plant, is but an employment practicei— -̂ It should be

treated accordingly:

When an employer or union has discriminated

in the past and when its present policies

renew or exaggerate discriminatory effects,

those policies must yield, unless there is

an overriding legitimate, non-racial business

purpose. Local 189, supra, 416 F.2d at 989.

This requirement of "business necessity" means more than mere

business purpose:

the "business necessity" doctrine must [do] ...

more than ... serve legitimate management func

tions. Otherwise, all but the most blatantly

discriminatory plans would be excused even if

they perpetuated the effects of past discrimina

tion ....

Necessity connotes an inestimable demand. To be

preserved, [a present employment practice] ....

must not only directly foster safety and effi

ciency of a plant, but also be essential to

those goals..... If the legitimate ends of

safety and efficiency can be served by a reason

ably available alternative system with less dis

criminatory effects, then the present policies

may not be continued.

Watkins v. Scott Paper Co., 530 F.2d 1159, 1168 (5th Cir. 1976),

quoting United States v. Jacksonville Terminal Co., 451 F.2d

418, 451 (5th Cir. 1971), cert denied, 406 U.S. 906 (1972 ).

20/ See, also, Evans v.~ United Airlines, Inc., 534 F.2d 1247

(7th Cir. 1976), cert granted, 45 U.S. L.W. 3321 (1976)

(continuous time-in-service, i.e., company service, is dis

criminatory if interruption in employment is caused by discriminatory discharge)

5_1/ Industry custom and the usually impartial application of

seniority schemes have dictated that seniority be the determining

factor in many instances. Other criteria, such as a strict merit system, may also be utilized.

-19-

See also United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446 F.2d

at 662. In the instant case, the defendants have failed

to meet this burden. This is not surprising in view of the

fact that the blacks involved have demonstrated an ability

to do the job. There is no indication that running the plant

with more senior employees amounts to a "business necessity."

There is no evidence that certain employees, or groups of

employees, who were retained when the black employees were

laid off were indispensable or possessed special skills. In

sum, there is no possible business necessity— ^ for a strict

preference for longer term employees to the disadvantage of

black employees as in this case.

C. Maintaining a Seniority System Which Disadvantages

Blacks Who Are Identifiable Victims of Past Racial

Discrimination Is, Of Itself, Present Discrimination As to Those Individuals.

The district court predicated its decision, in part, on

its view that there was no "legal wrong" against plaintiffs

after the Act:

Those who were discriminated against prior

to the passage of the Act can point to no

'underlying legal wrong' on which to base

their seniority claim; they seek merely to

restructure vested seniority right estab

lished prior to the effective date of the Act.(R. 620)

2_2/ ̂ The use of seniority is not for the benefit of employer.

It is basically^the product of unions' desire to provide

their members with some degree of security. See generallv Cooper and Sobol at 1 6 0 4 - 1 6 0 7 . ------------~

-20-

This view is erroneous for it ignores the essence of plain-

tiffs claim, namely, that the "underlying legal wrong" is

the seniority system which perpetuates the prior discrimina

tion and insures that they will not advance beyond the

position they were in before the Act:

When an employer adopts a system that neces

sarily carries forward the incidents of

discrimination into the present, his practice

constitutes on-going discrimination, unless

the incidents are limited to thosethat safety and efficiency require.

(emphasis added) Local 189, 416 F.2d at 994.

The mere fact that the system was established prior to the

Act will not protect it. If that were the case, a departmen

tal system would be similarly immune. In fact, courts have

looked to the post-Act effects of the prior discrimination

in modifying systems which were facially neutral and which,

absent the pre-Act discrimination, would be acceptable em

ployment practices. Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., supra.

Nance v. Union Carbide Corp., Consumer Products Division, supra.

The above reasoning conforms to judicial precedents

which have nullified employment preferences based on length

of service where blacks were prevented from accumulating the

relevant seniority. Thus, where craft unions have had a

history of excluding blacks, they may not use seniority in

granting preference for hiring hall referrals. United States

v. Sheet Metal Workers, Local 36, 416 F.2d 123 (8th Cir. 1969)—

23/ See, also, Dobbins v. Electrical Workers Local 212, 292

F. Supp. 413 Ts .dT Ohio 1968), aff'd as later modified, 472 F.2d

634 (6th Cir. 1973); EEOC v. Plumbers, Local Union No. 189,

311 F. Supp. 468 (S.D~ Ohio 1970) , vac'd on other grounds 438

F.2d 408 (6th Cir. 1971), cert denied, 404 U.S. 832 (1971)

-21-

Similarly, courts have forbidden the use of seniority as a

factor in promotions in cases where the employer had in the

past, discriminated in hiring on the basis of race. Rowe v .

General Motors Corp., 457 F.2d 348 (5th Cir. 1972).24/ The

common thread in these cases and in the "departmental

seniority" cases is that facially neutral seniority systems

are illegal in themselves under Title VII because they perpe

tuate practices that would lock blacks into inferior positions

in the employment s e t t i n g . i n the departmental setting,

24/ See, also Allen v. City of Mobile, 331 F.Supp. 1134,

IT42-43 (S.D. Ala. 1971), aff'd per curiam 466 F.2d (5th Cir.

1972), cert, denied 412 U.S. 909 1973. Afro-American Patrol

men's League v. Duck, 366 F. Supp. 1095, 1102 (N.D. Ohio, 1973),

aff'd in pertinent part 503 F.2d 294 (6th Cir. 1964); Harper

v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 359 F.Supp. 1187,

1203-1204 (D. Md. 1973), aff'd sub nom Harper v. Kloster 486

F.2d 1134 (4th Cir. 1973); hoy v. City of Cleveland, 8 FEP

Cases 614 (N.D. Ohio 1974); see also, Bridgeport Guardians,

Inc. v. Members of Civil Service Com'n, 497 F.2d 1113. 1115 (2nd Cir. 1974).

25/ It should be noted that the question of pre-Act discri

mination was broached by the Second Circuit in explaining its

decision in United States v. Bethlehem Steel Coro".. 446 F.2d 625 (1971) : * -------------------------------

[B]ethlehem's seniority list rankings resulted

from pre-1965 discrimination that was lawful,

however, reprehensible it may have been. Never

theless, we ordered the seniority ranking to

be changed, according to plant-wide rather than

departmental seniority, (footnote omitted).

Acha v. Beame, 531 F.2d 648, 652 (1976).

-22-

the black employee was hindered in bidding across department

lines by the effects of post-Act operation of the system.

Just as the past segregation in departments constantly asserted

itself in post-Act bidding, so too, the complete refusal to

hire in the past constantly reasserted itself whenever there

was a rollback or layoff.

D. Identifiable Victims of Pre-Act Discrimination

May Seek Redress From a Serniority System Which has

the Effect of Perpetuating That Prior Discrimination.

This Court's decision in Watkins v. United Steel

Workers of America, Local No. 2369, 516 F.2d 41 (1975) is

the starting point for the instant case:

We specifically do not decide the right of a

laid-off employee who could show that, but for

the discriminatory refusal to hire him at an

earlier time than the date of his actual em

ployment, or but for his failure to obtain

earlier employment because of exclusion of

minority employees from the work force, he

would have sufficient seniority to insulate him

against layoff. 416 F.2d at 45.

The court focused on the distinction between preferential

modification and remedial modification of seniority rankings

and held that blacks not otherwise personally discriminated

against could not seek seniority relief that would protect them

-23-

from lay-offs.— ^ The Court held that plant seniority was

acceptable on the facts of that particular case:

We hold, therefore, that the use of total

employment seniority to determine the order

of layoff of employees in this case does

not violate Title VII of the CivilRights

Act of 1964. (emphasis added)516 F .2d at 52

The instant case supplies the ingredient that was missing in

Watkins, i.e., identifiable victims of discrimination at the

hands of the employer.

The Second Circuit has recently decided that such

victims are indeed entitled to relief. Acha v. Beame, 531

F.2d 648 (1976).——/ In Acha, New York City had discriminated

26/ The court repeatedly referred to this distinction in denying relief in that case:

Inasmuch as none of plaintiffs have suffered

individual discrimination at the hands of the

Company, however, there is no past discrimina

tion toward them which the current maintenance

of the layoff system could possibly peroetuate. 516 F .2d at 47.

And again:

[T]here was an express intent [in Title VII] to

preserve_contractual rights of seniority as be

tween whites and persons who had not suffered

any effects of discrimination. 516 F.2d at 48

And finally:

Plaintiffs, who have never suffered discrimina

tion at the hands of the Company, are in no

better position to complain of the recall system

than are the white workers who were hired con

temporaneously with them. 516 F.2d at 48

27/ See, also, Chance v. Board of Examiners, 534 F.2d 648 (2nd Cir. 1976). — —

- 2 4 -

in the hiring of women to positions on the city police force.

Because of a downturn in the economy, the city was forced to

lay off a large number of officers. The lay-off affected

women more adversely than men because so many had been re

cently hired. The Court held that, as to identifiable victims

of prior discriminations, constructive seniority back to the

date a female would have been hired, absent discrimination,

28/was an appropriate remedy. The court rejected a claim that

the relief sought was an illegal preference, noting that it was

simply a remedial device within the power of a district court

when applied to persons who had actually been discriminated

against. 42 U.S.C. §2000e—5 (g). 531 F.2d 656. As the Court

correctly noted the seniority scheme as to these individuals

was discriminatory.— ^

28/ "If a female police officer can show that, except for

her sex, she would have been hired early enough to accumulate

sufficient seniority to withstand the current layoffs, then

her layoff violates section 703(a)(1) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C.

§2000e-2(a)(1), since it is based on sexual discrimination."

531 F.2d at 654. A plaintiff would be entitled to relief upon such a showing.

29/ The court realized that the discrimination in this type

oF case was even more pervasive than in the "departmental

seniority" case:

Plaintiffs here were not merely relegated to

inferior jobs, but were denied employment

altogether for discriminatory reasons.531 F.2d at 655.

-25-

The facts in Acha are analogous to those in the instant

case since the discriminatory hiring practices pre-dated

Title VII's applicability to local government entities.— ^

The decision clearly puts the situation in perspective:

[W]e believe that the relief plaintiffs seek

would prevent the perpetuation of the effects of past discrimination as to them.

(Emphasis added) 531 F.2d at 655.

There, as here, the operation of the seniority system was an

3JV pointed out by Chief Judge Kaufman's concurring opinion

in Acha, the layoffs applied in New York City to officers hired

after March, 1969. 531 F.2d at 657. Since Title VII became

applicable to local governments in 1972, any plaintiff who could

prove she had sufficient seniority to withstand layoff would

have to prove she would have been hired prior to March, 1969

and, of course, prior to 1972. In other words, she would have

to show discrimination prior to the effective date of the Act.

Judge Kaufman indicated further that the showing would even

encompass discrimination before Title VII was first enacted:

If so, relief should be available to an

individual who proves she took the 1964

examination for "policewoman," achieved

a score on that examination that, were

she a man, would have assured her employ

ment, but nevertheless was not appointed

until 1970 . . . . 531 F.2d at 657.

-26-

illegal employment practice when applied to identifiable

31/victims of past discrimination.—

The special context in which this case arises, i.e.,

seasonal work force variations, presents a particularly

appropriate situation for the proposed relief. In the lay

off cases cited above, much of the immediate problem results

from a general trend in the economy. In the instant case,

the past effects would be firmly entrenched even in a good

economy. Thus, the plaintiffs have had no opportunity to

overcome, through the passage of time, the disadvantage

32/occasioned by their prior exclusion from the work force.— ■

In effect, the employer was able to maintain a segregated

work force for approximately six months out of each year.

31/ The instant case is even more compelling since we are not

dealing with police officers where experience, rightly or

wrongly acquired, is arguably a business requirement. Where,

as here, experience will have a marginal effect, if any, on job

performance, seniority is a suspect basis for allocation of

work. See, Schaefer v. Tannian, 394 F. Supp. 1136, 1149

(E.D. Mich. 1975) (The Court raised the question, but stated

that there had been no showing of business necessity in any case).

32/ One effect of the continual lay-offs has been the inability

of black workers to participate in pension and health benefits

(R. 523, 524), as per the Collective Bargaining Agreement:

[Employment for pension] purposes shall be

deemed to be continuous so long as the

employee's seniority has not be interrupted

and so long as he has not been laid off for

six (6) months or longer at any one time.

-27-

The employer had what amounted to two classes of employees,

regular and supplemental, and the parallels between this

case and the "promotion-referral" cases become more evident.

E. The Closing of the Company's Atlanta Plant, While

Foreclosing Certain Seniority Relief for Plaintiffs,

Has Eliminated Equitable Objections Raised by Some Courts.

Defendant's plant in Atlanta is now closed. Conse

quently, there is no longer an existing seniority system to

be affected by any relief that plaintiffs may be granted in

this case.— ■' The issue now centers around plaintiffs' claims

for monetary relief based on the discriminatory lay-offs.

It is evident that one of the major obstacles faced

in Constructive seniority" cases is an equitable concern for

the expectations of white employees in the work force.— / Two

major points are usually stressed: first, that constructive

seniority for black employees defeats the expectations— / of

white employees:

33/ This development, of course, affects remedy, but does

not diminish defendant's inability for its illegal practice.

34/ See, e.g., Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., Inc.

u*s* ____/ 47 L. Ed. 2d 444, 471-482 (1976). (Separate opinions

of Chief Justice Burger and Justice Powerll, concurring in part

and dissenting in part); Meadows v. Ford Motor Co.. 510 F.2d 939

(1975), cert, denied (1976); Cooper and Sobol, supra, at 1604- 1607. — --

35/ Whether these expectations are legitimate is debatable.

It is possible that no job would have been available for some

incumbents if blacks had been hired in the first instance. See

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., Inc., supra, U.S. at~

_______t 47 L.Ed. 2d at 468, Cooper and Sobol, supra, at 1605.

-28-

[A seniority system] is justified among workers

by the concept that the older workers in point of

service have earned their retention of jobs by the length of prior service for the particular

employer. Meadows v. Ford Motor Co., 510 F.2d at 949.

Secondly, it is noted that the imposition of seniority relief

loses much of its deterrent effect because it does not impact

36/on the employer.

First, a retroactive grant of competitive-type

seniority usually does not directly affect the

employer at all. It causes only a rearrangement

of employees along the seniority ladder without

any resulting increase in cost. Thus, Title VII's

'primary objective' of eradicating discrimination

is not served at all for the employer is not de

terred from the practice. Franks v. Bowman

Transportation Co., Inc., ____ U.S. ____, 47 L.Ed.2d

at 475 (1976) (opinion of Justice Powell).

These equitable considerations are worth noting in the overall

context if only to point out that, even given these concerns,

constructive seniority is available as a remedy. Franks v.

Bowman Transportation Co., Inc., supra.; Meadows v. Ford Motor

Co., supra.

The relief now sought in the instant case is less per

vasive because of the plant closing. Competitive-type seniority

is not possible now. Some benefit-type seniority and backpay,

however, are available. The burden will fall solely on the dis

criminating employer:

36/ The Supreme Court makes a clear distinction between the

concept of "benefit-type" and "competitive-type" seniority,

the former determining pension rights, length of vacation and

similar company benefits, the latter determining an employee's

preferential rights against other employees. This argument, of

course, would not apply to benefit-type seniority since it, in

fact, places the burden directly on the employer.

-29-

As noted above, the granting of backpay and

benefit-type seniority furthers the pro

phylactic and make-whole objectives of the

statute without penalizing other workers.

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., Inc.,

____ U.S. at _____, 47 L.Ed. 2d at 475

(1976) (Opinion of Justice Powell).

REGARDLESS OF THE RESULT OF PLAINTIFFS'

TITLE VII CLAIM, THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED

IN NOT GRANTING RELIEF UNDER 42 U.S.C. §1981

Plaintiffs' complaint alleged a cause of action under

42 U.S.C. §1981. While the district court made no mention

of that section in granting the motion for summary judgment

(R 616-621), it apparently assumed that a seniority system

held immune under Title VII is also exempt under §1981. Such

a construction emasculates the remedial possibilities under

37/§1981— and ignores the relationship between the two statu

tory provisions.

Section 1981 assures black persons the same right

"to make and enforce contracts" as white citizens. This pro

scription against racial discrimination in contracts includes

a prohibition against racial discrimination in employment.— ^

37/ See, Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Co., 457 F.2d 1377

(4th Cir. 1972), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 982 (1972) (back pay

ordered for 1961 to 1962 under Section 1981); Also, cf.

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 494 F.2d 211

(5th Cir. 1974); Head v. Timken Roller Bearing Co., 486 F.2d

870 (6th Cir. 197311 ‘

38/ See e.g. Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421

U.S. 454 (1975); Sanders v. Dobbs Houses, Inc. 431 F.2d 1097,

1101 (5th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 401 U.S. 948 (1971) ;

Caldwell v. National Brewing Co., 443 F.2d 1044, 1045

(5th Cir. 1971), cert, denied 405 U.S. 916 (1972).

30

Nothing in Title VII restricts the remedy a court may fashion

to enforce or restore these rights. The Supreme Court has

continued to reject the assertion that §1981 is somehow limited

by Title VII :IV

. . . (L)egislative enactments in this area

have long evinced a general intent to accord

parallel or overlapping remedies against

discrimination 7/ . . . (T)he legislative

history of Title VII manifests a congressional

intent to allow an individual to pursue inde

pendently his rights under both Title VII and

other applicable state and federal statutes.

The clear inference is that Title VII was

designed to supplement, rather than supplant,

existing laws and institutions relating to

employment discrimination.

77 See, e.g. 42 U.S.C. Section 1981 (Civil

Rights Act of 1966); 42 U.S.C. Section 1983

Civil Rights Act of 1871) .

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36, 47-49 (1974).

The Court's decision in Alexander endorses both clear legis

lative history and principles settled in the lower courts.

In 1964 and 1972 Congress rejected amendments that would have

made Title VII the exclusive remedy for employment discrimina

tion. 110 Cong. Rec. 13650-52 (1964); H.R. Rep. No. 92-238

at p. 79 (1971); S. Rep. No. 92-415 at P. 24 (1971). Congress

thus intended that §1981 offer a separate and independent remedy

from that of Title VII.

39/ See, also Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421

U.S. at 461 (1975)1

We generally conclude, therefore, that the

remedies available under Title VII and

§1981, although related, and although

directed to most of the same ends, are

separate, distinct and independent.

31

Consistent with the independence of the two provisions,

courts have held that differing results occur depending on

which statutory scheme is utilized. The Supreme Court, for

example, in Washington v. Davis, ____ U.S. _____, 48 L.Ed.2d

597 (1976) held that the standard for adjudicating claims

under 1981 is not the same as the standard under Title VII.

The Courts of Appeals have similarly recognized differences.

In Guerra v. Manchester Terminal Co., 498 F.2d 641 (5th Cir.

1974) this Court held that, although Title VII does not pro

hibit discrimination based on alienage,— ^ §1981 does.— '/

40/ See Espinoza v. Farah Manufacturing Co., 414 U.S. 86 (1973)

41/ The Court in Guerra noted that §1981 expresses

"a humane and remedial policy," and stated, "Congress intended

Title VII to be an important, but not the only, weapon in the

arsenal against employment discrimination." 498 F.2d at 650.

It justified holding that §1981 prohibits some forms of employ

ment discrimination that Title VII does not touch by reasoning

that in reconciling the two statutes, the goal must be:

to mitigate the harshness to those accused of employ

ment discrimination resulting from what one source

has characterized as "multiple jeopardy," [footnote

omitted] while preserving and protecting for those

complaining of discriminatory employment practices

the full panoply of remedies guaranteed them by the federal laws."46/

46/ We emphasize that though Title VII, §1981,

and Section 8 of the NLRA may overlap in the

area of employment discrimination, their in

fluence must not be exaggerated. They are

separate, independent statutes. The procedures

under them vary; the available remedies may

differ significantly, and, as the case at bar

illustrates, conduct creating liability under

one may not create liability under another.

498 F.2d at 658.

-32-

The Court in Alpha Portland Cement Co. v. Reese, 507 F.2d

607 (5th Cir. 1975), ruled that §1981 might authorize class

42/

The reasoning in theserelief where Title VII did not.'

cases applies equally to any exemption in Title VII that

43/might be occassioned by §703(h)—

To hold that the broad, unqualified language of §1981

is limited by Title VII would require finding that the later

statute repealed or superseded the earlier one, at least in

regard to seniority issues. Such repeals by implication are

not favored. Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535 (1974) (enactment

of Title VII did not repeal remedial provisions of existing law.— ^

42/ The court in Reese rejected a policy argument against

extension of §1981 remedies beyond the reach of Title VII, stating:

Accepting [the employer's] proposition arguendo,

the policy choice is one already made by Congress

in creating Title VII as a remedy supplemental to

and separate from that existent under §1981.

507 F.2d at 609 (footnote omitted).

43/ See, e.g. Contractors Association of Eastern Pennsylvania v .

Secretary of Labor, 442 F.2d 159, 172 (3rd Cir. 1971) cert, denied

404 U.S. 854 (1971) (§703(j) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(j),

companion section to §703(h), cannot limit remedies based on laws other than Title VII).

4 4 / See also Posades v. National City Bank, 296 U.S. 4 9 7 , 503

TT9'36) ("the intention of the legislature to repeal must be clear

and manifest"). Silver v. New York Stock Exchanqe, 373 U.S.341 (1963) “—

-33-

The notion that Title VII repealed pre-existing remedies

under §1981 has been rejected in this Circuit:

So, too, the equal employment provisions

of the same Civil Rights Act of 1964 do

not supersede the provisions of §1981,

which had its origins in the very same

section of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 as did §1982. . . .

Furthermore, occurrences within the Congress culminating in the passage of Title VII

strongly support the conclusion that it was

not intended to supercede existing remedies.

Sanders v. Dobbs Houses, Inc., 431 F.2d

1097, 1100 (1970) cert, denied 401 U.S. 948 (1971). ------

Other circuit court decisions have expoused this position,— ^

thus acceting to the mandate of the Supreme Court not to read

the civil rights legislation of the 1960's as narrowing the

relief available under the more general post-Civil Rights War

acts* Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409, 416 n. 20

(1968) ("the Civil Rights Act of 1968 [42 U.S.C. §§3601 et seq.]

does not mention 42 U.S.C. §1982, and we cannot assume that

Congress intended to effect any change, either substantive or

procedural, in the prior statute"); Sullivan v. Little Hunting

Park, Inc., 396 U.S. 229, 237-238 (1969) (Title II of Civil

45/ See e.g. Gresham v. Chambers, 501 F.ed 687 (2nd Cir. 1974);

Young v. International Telephone & Telegraph Co., 438 F.2d 757

(3rd Cir. 1971); Brady v. Bristol Myers Co., 459 F.2d 621 (8th Cir.

1972); Macklin v. Spector Freight Systems, Inc., 478 F.2d 979

(D.C. Cir. 1973); Waters v. Wisconsin Steel Works of International

Harvester Co., 427 F.2d 476 (7th Cir. 1970) cert, denied 400 U.S.911 (1970). ---- ------

34

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§2000a et seq., does not

supersede provisions of 42 U.S.C. §1982; cf. Tillman v.

Wheaton-Haven Rec. Ass'n., 410 U.S. 431 (1973).

Prior to 1963, the defendant systematically excluded

blacks from its work force. (R. 545-546) . This policy

clearly violated §1981. To subscribe to the theory that

exemption of a seniority system under Title VII would some

how protect that system from review under §1981 is to insulate

blatant discrimination from redress. The district court was

concerned with the absence of an "underlying legal wrong."

Surely, this reasoning would not apply to §1981 since there

was a legal wrong under §1981, the discriminatory refusal

to hire. The seniority system certainly perpetuates the

effect of this discriminatory practice. Any other construc

tion would be adverse to the Congressional intent to place

the "highest priority" on the fight against discrimination.

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver, supra., and would be logically

46/ 47/inconsistent.— ' There is no difference in kind between

46/ It has already been noted that to deny relief in the

instant case, while granting it in departmental seniority

cases, would create the anomalous result of rewarding an

employer for the thoroughness of his discrimination. The

following example indicates a serious flaw in this approach.

Consider employer A. Prior to the effective date of Title II,

A fires all black employees. When Title VII comes into effect,

he hires workers in a non-discriminatory manner and uses com

pany seniority as the basis for employment decisions. In spite

of the prior overt act of discrimination, the same reasoning

that would protect th employer in the instant case, would

protect him in the hypothetical case. The syllogism would run thus

35

Respectfully submitted,

Kent Spriggs

324 N. College Avenue

Tallahassee, Florida 32301

N. David Buffington

88 Walton Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

Jack Greenberg

Ronald L. Ellis

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs Appellants

37