Legal Defense Fund Defends Man Against Boycott Charge Before U.S. Supreme Court

Press Release

February 20, 1964

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Loose Pages. Legal Defense Fund Defends Man Against Boycott Charge Before U.S. Supreme Court, 1964. db19f5a7-bd92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/52879d71-1cf9-4e4a-91a2-221542aa24c7/legal-defense-fund-defends-man-against-boycott-charge-before-us-supreme-court. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

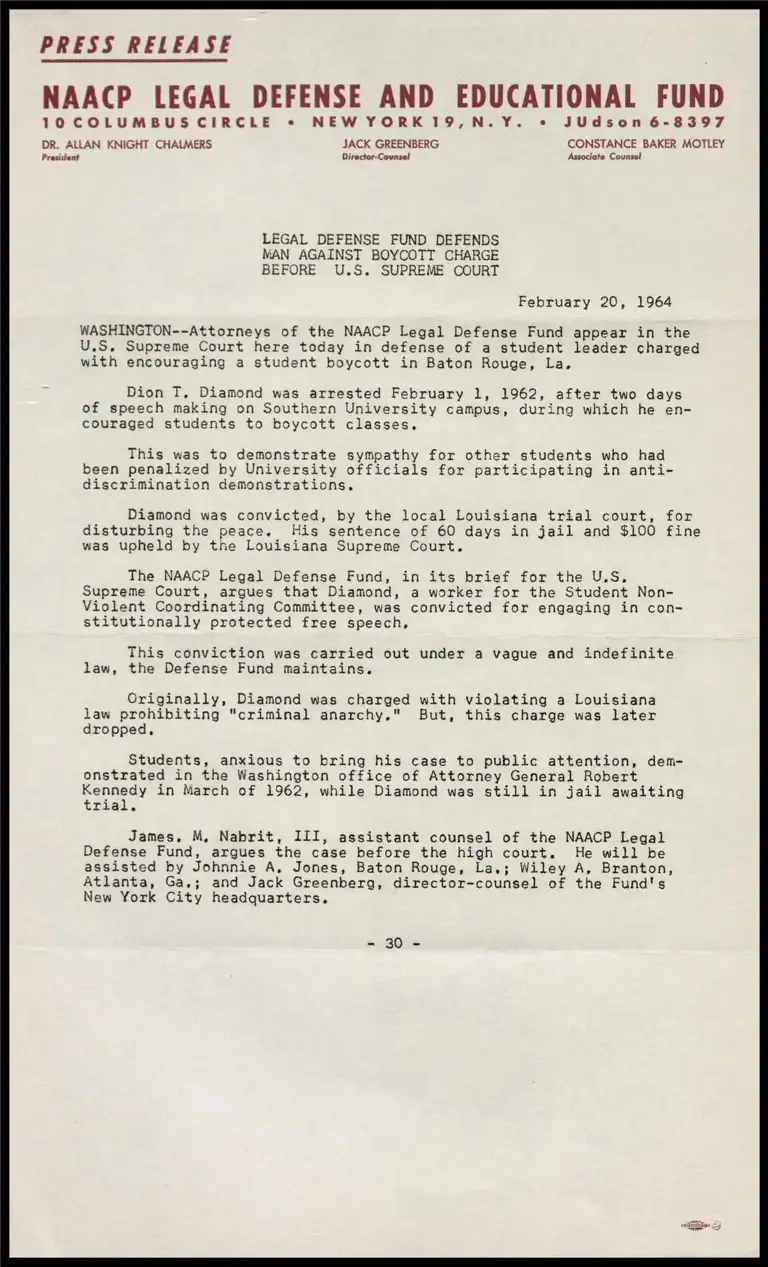

PRESS RELEASE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

TOCOLUMBUS CIRCLE + NEW YORKI19,N.Y. © JUdson 6-8397

DR. ALLAN KNIGHT CHALMERS JACK GREENBERG CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY

President Director-Counsel Associate Counsel

LEGAL DEFENSE FUND DEFENDS

MAN AGAINST BOYCOTT CHARGE

BEFORE U.S. SUPREME COURT

February 20, 1964

WASHINGTON--Attorneys of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund appear in the

U.S, Supreme Court here today in defense of a student leader charged

with encouraging a student boycott in Baton Rouge, La.

Dion T, Diamond was arrested February 1, 1962, after two days

of speech making on Southern University campus, during which he en-

couraged students to boycott classes.

This was to demonstrate sympathy for other students who had

been penalized by University officials for participating in anti-

discrimination demonstrations.

Diamond was convicted, by the local Louisiana trial court, for

disturbing the peace. His sentence of 60 days in jail and $100 fine

was upheld by the Louisiana Supreme Court.

The NAACP Legal Defense Fund, in its brief for the U.S,

Supreme Court, argues that Diamond, a worker for the Student Non-

Violent Coordinating Committee, was convicted for engaging in con-

stitutionally protected free speech,

This conviction was carried out under a vague and indefinite

law, the Defense Fund maintains.

Originally, Diamond was charged with violating a Louisiana

law prohibiting "criminal anarchy," But, this charge was later

dropped,

Students, anxious to bring his case to public attention, dem-

onstrated in the Washington office of Attorney General Robert

Kennedy in March of 1962, while Diamond was still in jail awaiting

trial.

James, M, Nabrit, III, assistant counsel of the NAACP Legal

Defense Fund, argues the case before the high court. He will be

assisted by Johnnie A, Jones, Baton Rouge, La,; Wiley A, Branton,

Atlanta, Ga,; and Jack Greenberg, director-counsel of the Fund's

New York City headquarters.

aaOue