Mississippi's Anti-Negro Voting Laws and Anti-NAACP Laws Challenged

Press Release

March 17, 1958

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Loose Pages. Mississippi's Anti-Negro Voting Laws and Anti-NAACP Laws Challenged, 1958. 01852469-bc92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/52c38cb5-04f1-47e6-a0e5-0df44592a399/mississippis-anti-negro-voting-laws-and-anti-naacp-laws-challenged. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

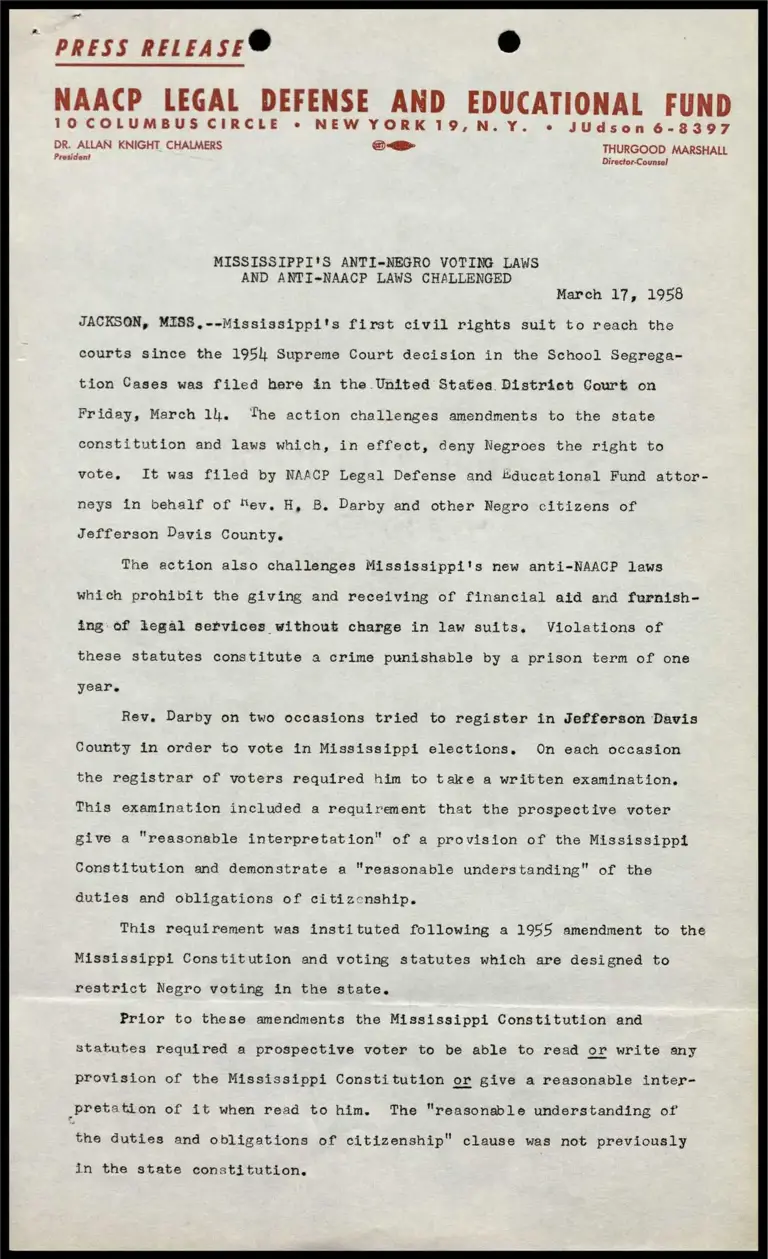

PRESS RELEASE® e

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

TO COLUMBUS CIRCLE + NEW YORK 19,N.Y. © JUdson 6-8397

DR. ALLAN KNIGHT CHALMERS oS THURGOOD MARSHALL President Director-Counsel

MISSISSIPPI'S ANTI-NEGRO VOTING LAWS

AND ANTI-NAACP LAWS CHALLENGED

March 17, 1958

JACKSON, MISS,--Mississippi'ts first civil rights suit to reach the

courts since the 195 Supreme Court decision in the School Segrega-

tion Cases was filed here in the United Statea District Court on

Friday, March 1). ‘The action challenges amendments to the state

constitution and laws which, in effect, deny Negroes the right to

vote, It was filed by NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund attor-

neys in behalf of “ev. H, 8. Darby and other Negro citizens of

Jefferson Davis County.

The action also challenges Mississippi's new anti-NAACP laws

which prohibit the giving and receiving of financial aid and furnish-

ing of legal services without charge in law suits, Violations of

these statutes constitute a crime punishable by a prison term of one

year.

Rev. Darby on two occasions tried to register in Jefferson Davis

County in order to vote in Mississippi elections. On each occasion

the registrar of voters required him to take a written examination,

This examination included a requirenent that the prospective voter

give a "reasonable interpretation" of a provision of the Mississippt

Constitution and demonstrate a "reasonable understanding" of the

duties and obligations of citizenship.

This requirement was instituted following a 1955 amendment to the

Mississippi Constitution and voting statutes which are designed to

restrict Negro voting in the state.

Prior to these amendments the Mississippi Constitution and

statutes required a prospective voter to be able to read or write any

provision of the Mississippi Constitution or give a reasonable inter-

_pretation of it when read to him. The "reasonable understanding of

the duties and obligations of citizenship" clause was not previously

in the state constitution.

-2=

On each occasion on which Rev. Darby sought to register, he was

denied the right on the ground that he had failed the examination,

Mississippi was one of the first deep-south states to enact legis-

lation aimed at cutting off NAACP Legal Defense Fund aid to southern

Negroes in civil rights litigation. These laws, enacted in February,

1956, make it a crime to receive or give legal services without charge

in a law suit or to accept financial assistance for the purpose of com-

mencing or prosecuting further any law suit,

Rev. Darby and his lawyers seek a federal court injunction enjoin-

ing Mississippi's Attorney General Joe T. Patterson from enforcing

these laws and enjoining the registrar of voters of Jefferson Davis

County from enforcing the amendments to the Mississippi Constitution

and statutes which are designed to restrict Negro voting.

Rev. Darby's Mississippi lawyer, R. Jess Brown of Vicksburg, has

sought the financial and legal aid of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

The Defense Fund is giving financial aid and furnishing legal counsel

to Rev. Darby.

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund attorneys in the case

are Thurgood Marshall and Constance Baker Motley of New York.

E30 he