The State of Washington v. Muhammad Shabazz Farrakhan Brief in Opposition to Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 6, 2003

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. The State of Washington v. Muhammad Shabazz Farrakhan Brief in Opposition to Certiorari, 2003. 92ae3e67-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/52c8fc6a-1295-4500-b2bf-814a0f19bf3f/the-state-of-washington-v-muhammad-shabazz-farrakhan-brief-in-opposition-to-certiorari. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

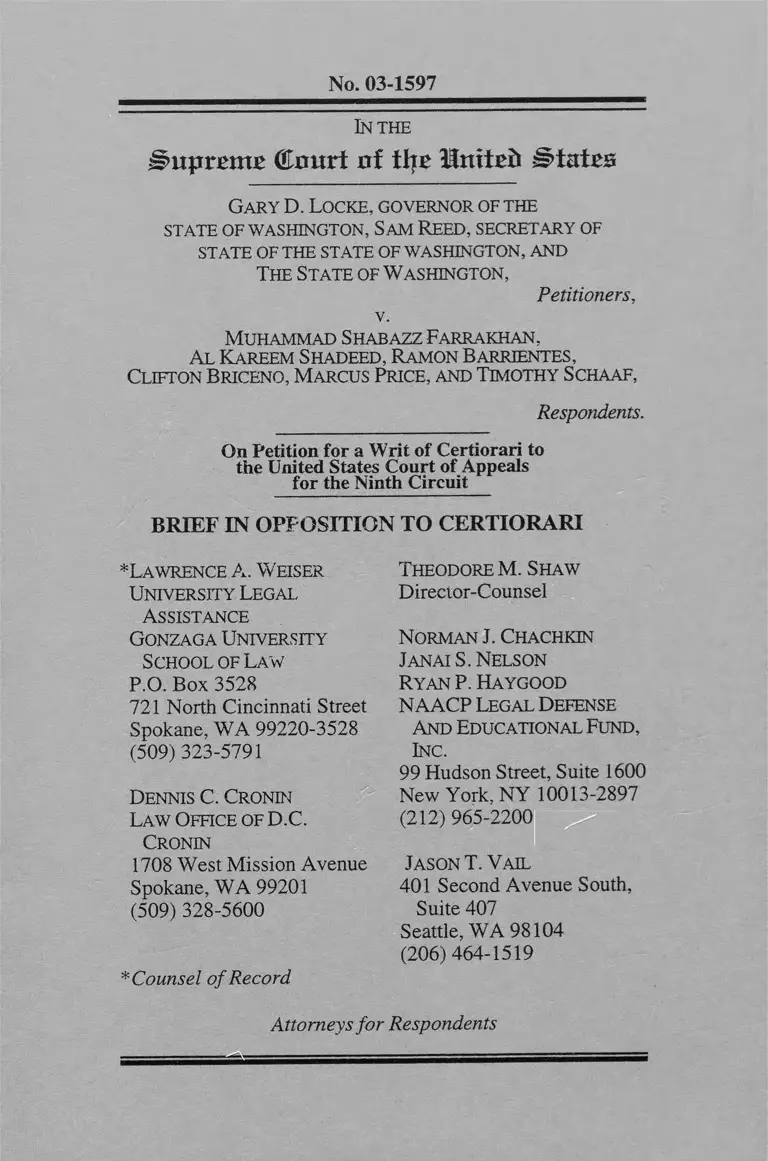

No. 03-1597

In THE

#upm n£ Court of tlje Untied s ta te s

Gary D. Locke, governor of the

STATE OF WASHINGTON, S AM REED, SECRETARY OF

STATE OF THE STATE OF WASHINGTON, AND

The State of Washington,

Muhammad ShabazzFarrakhan,

Al Kareem Shadeed, Ramon Barrjentes,

Clifton Briceno, Marcus Price, and Timothy Schaaf,

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

721 North Cincinnati Street NAACP Legal Defense

Spokane, WA 99220-3528 And Educational Fund,

Respondents.

On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to

the United States Court of Appeals

for the Ninth Circuit

^Lawrence A. Weiser

University Legal.

Assistance

Gonzaga University

School of Law

P.O. Box 3528

Theodore M. Shaw

Director-Counsel

Norman J. Chachkin

Janai S. Nelson

Ryan P. Haygood

Dennis C. Cronin

Law Office of D.C.

Cronin

1708 West Mission Avenue

(509) 323-5791 Inc.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013-2897

(212) 965-2200

Spokane, WA 99201

(509) 328-5600

Jason T. Vail

401 Second Avenue South,

Suite 407

Seattle, WA 98104

(206) 464-1519

* Counsel o f Record

Attorneys fo r Respondents

COUNTER-STATEMENT OF THE

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether § 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which

prohibits any voting qualification or prerequisite to voting that

results in the denial of voting rights on account of race, can be

applied to the Washington state laws that deny the right to vote

to persons convicted of a felony.

PARTIES TO THE PROCEEDING

The Petition for a Writ of Certiorari (“Pet.”) correctly

identifies the parties to the proceeding below. Respondents

wish to inform the Court that, while Respondent Muhammad

Shabazz Farrakhan has been referred to by that name

consistently throughout the course of these proceedings, his

name was not changed to Muhammad Shabazz Farrakhan

through formal legal proceedings. Mr. Farrakhan’s legal name

is Ernest Walker.

ii

Counter-Statement of the Question Presented...................... i

Parties to the Proceeding......................................................... ii

Table of Authorities..................................................................v

Counter-Statement of the Case ............ 1

A. Felon Disfranchisement In Washington S ta te .........1

B. Procedural H isto ry ....................................................... 1

REASONS FOR DENYING THE WRIT 6

Introduction ............................................................................ 6

I Certiorari Should Be Denied Because Petitioners

Failed To Raise Their Plain Statement

Argument At The Appellate Level 7

II Petitioners Overstate The Extent Of Any Circuit

Conflict; This Court Has Denied Certiorari

Where The Alleged Conflict Was More

Developed Than That Presented H e re ................... 9

III The Judgment Below Is Interlocutory And

Review At This Stage Would Be Premature . . . 11

iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

IV

IV The Court Below Decided Correctly That The

VRA Applies To Felon Disfranchisement Laws

And Further Review Is Unnecessary . . . . . . . . . 12

A. The Plain Meaning Of § 2 Is

Unambiguous On Its Face ...................... 13

B. Even Assuming The Plain Statement

Rule Applies, The Ninth Circuit Was

Correct In Holding That § 2 Covers

W ash in gton ’s Felon D isfran

chisement Laws .................................... 16

1. Covering Felon Disfranchisement

Under § 2 Does Not A lter

Impermissibly The Balance Between

Federal And State Pow ers..........................16

2. The Legislative History Of §§ 2 And

4 Demonstrates Congress’ Clear

Intent Not To Exclude Felon

Disfranchisement From The Reach

Of § 2 ..................................................... . . . . 1 8

C. Application Of § 2 Of The Voting Rights

Act To Washington’s Felon Disfran

chisement Scheme Is Entirely Consistent

With This Court's Ruling In Richardson

v. Ramirez ....................... 20

Conclusion............... 23

TABLE OF CONTENTS (continued)

Page

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Cases:

Adams v. Robertson,

520 U.S. 83 (1997)................................................... 8n-9n

Adickes v. S.H. Kress & Co.,

398 U.S. 144(1970)................................................... 7 ,8

Allen v. State Board o f Elections,

393 U.S. 544 (1969)....................................................... 18

Baker v. Pataki,

85 F.3d 919 (2d Cir. 1996)............................................. 9n

Brotherhood o f Locomotive Firemen & Enginemen

v. Bangor & Aroostook R.R. Co.,

389 U.S. 327(1967)................................................. 11-12

Bunting v. Mellen,

124 S. Ct. 1750(2004)................................................... 11

California v. Taylor,

353 U.S. 553 (1957)........................................................... 7

Caminetti v. United States,

242 U.S. 470(1917)....................................................... 14

Campos v. City o f Houston,

113 F.3d 544 (5th Cir. 1997) 14

VI

Chisom v. Roemer,

501 U.S. 380 (1991)................. ............ 16, 17, 18, 19, 21

Circuit City Stores, Inc. v. Adams,

532 U.S. 105 (2001).......................................... .. 18-19

City o f Rome v. United States,

446 U.S. 156(1980)..................... ................................. 16

City o f Springfield v. Kibbe,

480 U.S. 257 (1987)........................................................... 7

Connecticut National Bank v. Germain,

503 U.S. 249(1992).............................................. 14

Demarest v. Manspeaker,

498 U.S. 184(1991)............................................ 14

Durden v. California,

531 U.S. 1184(2001)..................................................... 11

Farrakhan v. Locke,

No. CS-96-76-RHW, 2000 U.S. Dist. LEXIS

22212 (E.D. Wash. Dec. 1, 2000), a ff d in part and

rev’d in part sub nom. Farrakhan v. Washington,

338 F.3d 1009 (9th Cir. 2 0 0 3 )....................... .. ..............3

Farrakhan v. Locke,

987 F. Supp. 1304 (E.D. Wash. 1997) ............. .. 2, 7n, 22

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

Cases (continued):

Cases (continued):

Farrakhan v. Washington,

359 F.3d 1116 (9th Cir. 2 0 0 4 )........................................ 6

Farrakhan v. Washington,

338 F.3d 1009 (9th Cir. 2003) . . 3, 4, 5, 9, 10, 11, 12, 22

France v. Pataki,

71 F.Supp. 2d 1317 (S.D.N.Y. 1999)..................... 14-15

Gregory v. Ashcroft,

501 U.S. 452 (1991)............................................... 15, 17n

Hilton v. South Carolina Public Railways Commission,

502 U.S. 197(1991)....................................................... 15

Holley v. City o f Roanoke,

162 F. Supp. 2d 1335 (M.D. Ala. 2001) ..................... 14

Hunter v. Underwood,

471 U.S. 222 (1985)................................... 20

Husty v. United States,

282 U.S. 694(1931) .................................... 8

International Brotherhood o f Teamsters v. United States,

431 U.S. 324(1977)................................................. 19-20

vii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

Johnson v.Bush,

353 F.3d 1287 (11th Cir. 2003), vacated, 2004 WL

1609101 (11th Cir. July 20, 2004) (No. 02-14469) . . . 10

Johnson v. DeSoto County Board o f Commissioners,

72 F.3d 1556 (11th Cir. 1 9 9 6 )..................... ................ 14

Lackey v. Texas,

514 U.S. 1045 (1995)...................................................... 11

Lawn v. United States,

335 U.S. 339(1958)........................................ 7

Lee v. Bankers Trust Co.,

166 F.3d 540 (2d Cir. 1999).......................................... 15

McCray v. New York,

461 U.S. 961 (1983)...................................... ................ 11

McNeil v. Legislative Apportionment Commission

o f New Jersey,

124 S. Ct. 1068 (2004)................................................... 10

Moskal v. United States,

498 U.S. 103 (1990)................................................... 18

Muntaqim v. Coombe,

366 F.3d 102 (2d Cir. 2004)............. .............. .. 9, 10

viii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

Cases (continued):

IX

Cases (continued):

New Rochelle Voter Defense Fund v. City o f

New Rochelle,

308 F. Supp. 2d 152 (S.D.N.Y. 2 0 0 3 ) .......................... 14

Nixon v. Kent County,

76 F.3d 1381 (6th Cir. 1996) ......................................... 14

Pennsylvania Department o f Corrections v. Yeskey,

524 U.S. 206 (1998)................................................... 8, 18

Ratzlaf v. United States,

510 U.S. 135 (1994)....................................................... 15

Reno v. Bossier Parish School Board,

520 U.S. 471 (1997)............................................... 17,20n

Richardson v. Ramirez,

418 U.S. 24 (1974)............................................. 20,21,22

Russello v. United States,

464 U.S. 16(1983)......................................................... 20

Salinas v. United States,

522 U.S. 52(1997)......................................................... 15

Schick v. Schmutz (In re Venture Mortgage Fund, L.P.),

282 F.3d 185 (2d Cir. 2002).................................... .. • • 14

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

X

Sedima, S.P.R.L. v. Imrex Co.,

473 U.S. 479 (1985)........................................................ 18

United States v. Ron Pair Enterprises, Inc.,

489 U.S. 235 (1989)............................................... .. 14

VMIv. United States,

508 U.S. 946(1993)........................................................ 12

Wesley v. Collins,

791 F.2d 1255 (6th Cir. 1 9 8 6 )............. ................... . 9, 22

Williams v. State Board o f Elections,

696 F. Supp. 1563 (N.D. 111. 1988) .......................... .. . 15

Constitutions, Statutes, and Rules:

U.S. Const, amend. XIV ............................................. 21

Wash. Const. Article VI, § 3 ................... ....................... .. 1

§ 2, Voting Rights Act of 1965,

42 U.S.C. § 1973 ........................................ .. passim

§ 4, Voting Rights Act of 1965,

42 U.S.C. § 1 9 7 3 b .......... ........................... ............ 18, 19

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

Cases (continued):

XI

Constitutions, Statutes, and Rules (continued):

§ 5, Voting rights Act of 1965,

42U.S.C. § 1973c ................... 19n

42U.S.C. § 1973gg-6(g) ..........................................................1

Wash. Rev. Code § 9.94A.637 ................................................. 1

Wash. Rev. Code § 9.94A.875 ................................................. 1

Wash. Rev. Code § 9.96.050 ................................................... 1

Wash. Rev. Code § 10.64.021 ................................................. 1

Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(b)(6)......................................................... 2

Other Authorities'.

Brief for Appellees, Farrakhan v. Washington,

338 F.3d 1009 (9th Cir. 2003) (No. 01-35032).............5

Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, McNeil v. Legislative

Apportionment Commission o f New Jersey,

124 S. Ct. 1068 (2004) (No. 03-652)............................ 10

Petition for Rehearing and Petition for Rehearing

En Banc, Farrakhan v. Washington, 338 F.3d

1009 (9th Cir. 2003) (No. 01-35032)..................... 7n-8n

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

xii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (continued)

Page

Other Authorities (continued):

Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary (1 9 9 0 )___ 13n

Webster’s Third New International Dictionary (2002) . . 13n

1

This case concerns the scope of § 2 of the Voting Rights

Act of 1965 (“VRA” or “Voting Rights Act”), and whether §

2 provides a basis for Respondents to challenge Washington’s

felon disfranchisement scheme, which denies suffrage to

persons upon conviction of a felony.

A. Felon Disfranchisement In Washington State

Washington’s statutory scheme for felon disfranchisement

is rooted in Article VI, § 3 of the Washington Constitution,

App. 93a.1 The process for revocation of the offender’s right

to vote is administrative in nature; it is a collateral consequence

of “convicted felon” status, not a part of the adjudication of

guilt and sentencing of the offender. Upon the offender’s

conviction, notice is sent to the county auditor who revokes the

offender’s voter registration, if any. See Wash. Rev. Code §

10.64.021, App. 99a (convictions in state court); 42 U.S.C. §

1973gg-6(g) (convictions in federal court). Because loss of the

right to vote is based entirely upon the offender’s status as a

felon, the specific type or degree of the crime for which the

offender was convicted plays no role in the automatic

revocation of the right to vote. The offender may later seek to

reinstate the right to vote through a statutory process. See

Wash. Rev. Code § 9.94A.637, App. 94a (determinate

sentences); id. § 9.96.050, App. 97a (indeterminate sentences);

id. § 9.94A.875 (clemency and pardons board).

B. Procedural History

Respondents in this case are currently denied the right to

vote in Washington because they each were convicted of a

felony. Muhammad Shabazz Farrakhan (also known as Ernest

Walker, see supra p. ii), A1 Kareem Shadeed, and Marcus Price

COUNTER-STATEMENT OF THE CASE

1 Citations in this format are to the Appendix to the Petition for

a Writ of Certiorari.

2

are African-American; Clifton Briceno and Timothy Schaaf are

Native-American; and Ramon Barrientes is Hispanic-

American. None of the Respondents is currently eligible for

restoration of voting rights under Washington’s statutory

restoration procedure.

Respondents filed this action in the United States District

Court for the Eastern District of Washington, challenging

Washington’s felon disfranchisement scheme under the Voting

Rights Act and the First, Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, Ninth,

Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments to the United States

Constitution. Respondents argued that felon disfranchisement

denies racial minorities the right to vote on the basis of race and

has the effect of diluting racial minority voting strength.

Appellants moved to dismiss Respondents’ claims pursuant

to Fed. R. Civ. P. 12(b)(6). The district court sustained

Respondents’ claims of vote denial under the Voting Rights

Act but dismissed their vote dilution claim under the Act and

their Constitutional claims. Farrakhan v. Locke, 987 F. Supp.

1304, 1315 (E.D. Wash. 1997), App. 67a, 90a.

Respondents subsequently filed a motion for summary

judgment. Respondents presented evidence to support a

“totality o f circumstances” argument, as required by § 2 of the

Voting Rights Act when challenging the racial effects of a

voting practice, including the following: evidence of

disparities in the treatment of minorities in the criminal justice

system; a history of race discrimination in the state of

Washington; and the tenuous public policy rationale for felon

disfranchisement. Petitioners responded with a cross-motion

for summary judgment, arguing that felon disfranchisement is

constitutionally permissible, that the VRA was not intended to

prohibit felon disfranchisement, and that, even if the VRA

applied to felon disfranchisement, Respondents did not present

sufficient evidence to satisfy the totality of circumstances

analysis.

3

In its ruling on the cross-motions for summary judgment,

the district court found that “the [felon] disenfranchisement

provision clearly has a disproportionate impact on racial

minorities . . . Farrakhan v. Locke, No. CS-96-76-RHW,

2000 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 22212, at *9 (E.D. Wash. Dec. 1,

2000), App. 54a, 59a, a ff’d in part and rev ’d in part sub nom.

Farrakhan v. Washington, 338 F.3d 1009 (9th Cir. 2003), and

that Respondents’ “evidence of discrimination within the

criminal justice system.. . is compelling,” id. at *14, App. 62a.

Despite these findings, the district court found that this

evidence could not be considered within the VRA’s totality of

circumstances analysis because such evidence creates a “causal

chain [that] runs, if at all, to a factor outside of the challenged

voting mechanism.” Id. at *10, App. 59a. After disregarding

evidence of disparities within the criminal justice system, the

district court held that Respondents failed to provide evidence

satisfying the totality of circumstances analysis and granted

summary judgment in favor of Petitioners. Id. at *18, App.

64a.

Respondents appealed to the United States Court of

Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, arguing that the district court

erred in failing to consider disparities in Washington’s criminal

justice system in the context of the VRA’s totality of

circumstances analysis. The court of appeals agreed, holding

that the totality of circumstances analysis “requires the court to

consider the way in which the disenfranchisement law interacts

with racial bias in Washington’s criminal justice system to deny

minorities an equal opportunity to participate in the state’s

political process,” Farrakhan v. Washington, 338 F.3d 1009,

1014 (9th Cir. 2003), App. la, 9a. The court of appeals further

held that in determining whether Washington’s felon

disfranchisement provisions produce a discriminatory result, a

court must consider factors external to the challenged voting

mechanism as well as voting practices themselves. To do

otherwise, the court stated, would “effectively read an intent

4

requirement back into the VRA, in direct contradiction of the

clear command of the 1982 Amendments to Section 2 [of the

VRA].” Id., 338 F.3d at 1019, App. 19a. Because the district

court found that the Respondents’ evidence was “compelling,”

the court o f appeals posited that, “had the district court properly

interpreted the causation requirement under the totality of the

circumstances test instead of applying its novel ‘by itself

causation standard, the court might have reached a different

conclusion.” Id., 338 F.3d at 1020, App. 22a (footnote

omitted). Accordingly, the court of appeals reversed and

remanded the case to the district court to evaluate the record

evidence in light o f the correct analysis. Id., 338 F.3d at 1020,

App. 23a.

The court of appeals panel explicitly agreed with the district

court that the VRA covered felon disfranchisement laws:

As a preliminary matter, we agree with the district court

that Plaintiffs’ claim of vote denial is cognizable under

Section 2 o f the VRA. Felon disenfranchisement is a

voting qualification, and Section 2 is clear that any voting

qualification that denies citizens the right to vote in a

discriminatory manner violates the VRA. 42 U.S.C. §

1973. Indeed, the Supreme Court has made clear that states

cannot use felon disenfranchisement as a tool to

discriminate on the basis of race, see Hunter v. Underwood,

471 U.S. 222, 233, 105 S.Ct. 1916, 85 L.Ed.2d222 (1985)

(holding that where racial bias motivated its original

enactment, a facially neutral felon disenfranchisement law

violated the Equal Protection Clause), and Congress

specifically amended the VRA to ensure that, “in the

context of all the circumstances in the jurisdiction in

question,” any disparate racial impact of facially neutral

voting requirements did not result from racial

discrimination, Senate Report at 27; see also Chisom v.

Roemer, 501 U.S. at 394 & n. 21, 111 S.Ct. 2354.

5

Permitting a citizen, even a convicted felon, to

challenge felon disenfranchisement laws that result in either

the denial of the right to vote or vote dilution on account of

race animates the right that every citizen has of protection

against racially discriminatory voting practices. Although

states may deprive felons of the right to vote without

violating the Fourteenth Amendment, Richardson v.

Ramirez, 418 U.S. 24, 54-55, 94 S.Ct. 2655, 41 L.Ed.2d

551 (1974), when felon disenfranchisement results in denial

o f the right to vote or vote dilution on account o f race or

color. Section 2 affords disenfranchised felons the means to

seek redress.

338 F.3d at 1016, App. 13a-14a (footnote omitted).

The panel did not discuss the “plain statement” rule because

Petitioners did not rely upon it in their brief to the court of

appeals. The brief discussed the legislative history of the VRA,

which Petitioners said “clearly demonstrates that [the statute]

was never intended to extend the voting rights of convicted

felons.” Brief for Appellees, Farrakhan v. Washington, 338

F.3d 1009 (9th Cir. 2003) (No. 01-35032), at 13. Petitioners

added in a footnote that “[t]he same conclusion would follow

from the application of the ‘plain statement rule.’ Federal

courts apply the ‘plain statement rule’ as a rule of statutory

construction to limit the involvement of the federal courts in

traditional state matters absent clear Congressional intent to the

contrary___” Id. at 13 n.3. Petitioners did not discuss, in the

balance of that short footnote, the circumstances in which this

Court has applied the “plain statement rule,” i.e., when a statute

is ambiguous and unclear, see infra § IV.A., much less ask the

court of appeals to affirm the district court’s judgment in their

favor on these alternate grounds.

The court of appeals rejected Petitioners’ subsequent

petition for rehearing and rehearing en banc. Dissenting from

that action, Judge Kozinski wrote that “the district court’s

6

decision granting summary judgment was correct, even if for

the wrong reasons,” Farrakhan v. Washington, 359 F.3d 1116,

1119 (9th Cir. 2004), App. 37a. He argued that the

interpretation of the VRA supported by the majority conflicted

with recent decisions of this Court and the United States

Constitution. 359 F.3d at 1124, App. 46a-47a.

REASONS FOR DENYING THE WRIT

Introduction

The conflict between the decision below and a single

contrary appellate ruling with precedential weight does not

warrant this Court’s exercise of its discretionary certiorari

jurisdiction. Given the benefits of further litigation in the lower

courts and the absence of need for immediate review

(especially where the decision below correctly applies a

provision of federal law), this Court should deny the petition

and permit the case to be litigated to final judgment, at which

time both the necessity, if any, of deciding the federal question

and the full factual context for doing so will be clear. Because

the “plain statement” issue on which Petitioners centrally rely

before this Court, see Pet. at 17-20, was neither raised nor

discussed below, Petitioners’ claim of conflict among the

circuits is overstated.

Moreover, whatever conflict may exist is, at best, one of

theory because the decisions that have addressed the question

of the VRA’s application to felon disfranchisement laws have

not yet had any practical effect upon state law since they have

not yet resulted in final judgments. Thus, Petitioners now seek

interlocutory review of a federal question that might be

unnecessary if the case were permitted to proceed to final

judgment. Finally, the Ninth Circuit correctly decided that the

VRA applies to felon disenfranchisement laws — a decision

7

supported by the text, legislative history, and even the “plain

statement” analysis of the Voting Rights Act.

I

Certiorari Should Be Denied Because Petitioners

Failed To Raise Their Plain Statement Argument At

The Appellate Level.

This Court has ruled that it “will not decide questions not

raised or litigated in the lower courts.” City o f Springfield v.

Kibbe, 480 U.S 257, 259 (1987) (citing California v. Taylor,

353 U.S. 553, 556 n.2 (1957)); see also Adickes v. S.H. Kress

& Co., 398 U.S. 144,147 n.2 (1970) (“Where issues are neither

raised before nor considered by the Court of Appeals, this

Court will not ordinarily consider them.”); Lawn v. United

States, 355 U.S. 339, 362-63 n.16 (1958) (noting that “[o]nly

in exceptional cases will this Court review a question not raised

in the court below”).

Petitioners did not raise the “plain statement” argument

before the Ninth Circuit,2 3 either on direct appeal, see supra p.

5, or in their request for rehearing and rehearing en banc?

2 Petitioners raised the “plain statement” argument before the

district court, which held that the plain statement rule does not apply

to the VRA. Farrakhan v. Locke, 987 F. Supp. at 1308-09, App.

73a-74a.

3The issues Petitioners raised for en banc review were stated as

follows:

(1) “The panel decision conflicts with Salt River by allowing

this Voting Rights Act challenge to proceed on a record

demonstrating nothing more that statistical disparity^]” and

Consequently, as stated in the Petition, “the Ninth Circuit did

not discuss the application of the plain statement rule to the

Voting Rights Act.” Pet. at 9. Petitioners failed to inform this

Court, however, that they had not urged the court below to

uphold the grant of summary judgment in their favor on the

basis of the plain statement rule.

Where, as here, an issue has not been decided by the court

of appeals, certiorari review of that issue is routinely denied.

See, e.g., Pa. D ep’t o f Corrs. v. Yes key, 524 U.S. 206, 212

(1998) (declining to address whether application o f the ADA to

state prisons is a constitutional exercise of Congress’ power

under the Commerce Clause or § 5 of the Fourteenth

Amendment because the issue was not addressed by the lower

courts); Adickes, 398 U.S. at 147 n.2 (1970) (declining to hear

petitioner’s challenge to the Civil Rights Cases because an

“examination of the record showfed] that petitioner never

raised any issue concerning the 1875 statute before the Court of

Appeals”); Hasty v. United States, 282 U.S. at 701-02 (“[W]e

do not consider [the rulings on the evidence], since they were

not assigned as error on the appeal to the Court of Appeals, and

it does not appear that they were presented or passed upon

there.”). The absence of any mention of the plain statement

rule in the issues on appeal and Petitioners’ failure to avail

themselves of every opportunity to raise this issue in the court

of appeals as a basis for affirmance militate strongly in favor of

denying certiorari.4

(2) “The panel decision similarly conflicts with the decision of

the Sixth Circuit in Wesley v. Collins, which concluded that

statistical disparity in felon disfranchisement does not establish a

violation of the Voting Rights Act.”

Petition for Rehearing and Petition for Rehearing En Banc,

Farrakhan v. Washington, 338 F.3d 1009 (No. 01-35032), at 3.

4 This Court used similar reasoning in Adams v. Robertson, 520

U.S. 83 (1997) in dismissing the case, holding that certiorari was

9

Petitioners Overstate The Extent Of Any Circuit

Conflict; This Court Has Denied Certiorari Where

The Alleged Conflict Was More Developed Than

That Presented Here.

Only three courts of appeals have issued opinions of

precedential effect concerning the VRA’s application to felon

disfranchisement laws.5 See Farrakhan v. Washington, 338

F.3d 1009 (9th Cir. 2003), App. la; Muntaqim v. Coomhe, 366

F.3d 102 (2d Cir. 2004); Wesley v. Collins, 791 F.2d 1255 (6th

Cir. 1986). Only two of those opinions squarely confront the

question whether the Voting Rights Act applies to felon

disfranchisement: Muntaqim, 366 F.3d at 115 (holding that the

VRA does not apply to felon disfranchisement); Farrakhan,

338 F.3d at 1016, App. 13a-14a (holding the reverse). As the

Second Circuit observed in Muntaqim, the Sixth and Eleventh

Circuits have assumed without expressly deciding that the

Voting Rights Act applies to felon disfranchisement.

Muntaqim, 366 F.3d at 112 & n.12 {citing Wesley, 791 F.2d at

II

improvidently granted since the federal constitutional argument was

never presented to the state supreme court. Id. at 85. (The Court

explicitly noted that it would reach this result whether it considered

the requirement that the argument be fairly presented to the state

court to be jurisdictional or to be prudential in nature. Id. at 90.)

Although the petitioners in Adams devoted two pages of their brief

in the state court to the discussion of a case relevant to the

constitutional argument, this Court found the discussion “unrelated”

and “insufficient” to meet the requirement. Id. at 88.

5 “Because the ten members of the Court who decided Baker

split evenly on its disposition, the opinions in that case have no

precedential effect, and the decision of the District Court was left

undisturbed.” Muntaqim v. Coombe, 366 F.3d 102, 107-08 (2d Cir.

2004) (discussing Baker v. Pataki, 85 F.3d 919, 921 n.2 (2d Cir.

1996)).

10

1259-61; Johnson v. Bush, 353 F.3d 1287, 1303-04 (11th Cir.

2003)). The Eleventh Circuit panel opinion has since been

vacated by the grant of rehearing en banc, Johnson v. Bush,

2004 WL 1609101 (11th Cir. July 20, 2004) (No. 02-14469).

Further, of the two courts of appeals that have squarely

decided whether the VRA applies to felon disfranchisement

laws, only the Second Circuit in Muntaqim has applied the

“plain statement” rule, 366 F.3d at 104 (applying “plain

statement” rule on the grounds that construing the Voting

Rights Act to cover felon disfranchisement would alter the

balance of power between the federal and state governments),

making it the only court of appeals to adopt this approach. The

Ninth Circuit below, in deciding this question, referred to the

plain language of the VRA, holding that “[f]elon

disfranchisement is a voting qualification, and Section 2 is

clear that any voting qualification that denies citizens the right

to vote in a discriminatory manner violates the VRA.”

Farrakhan, 338 F.3d at 1016, App. 13a (citation omitted)

(emphasis in original). Thus, while the Second Circuit and the

court below ultimately reached different results, their rationales

are not directly in conflict to an extent that warrants this

Court’s intervention in this developing area of the law.

This Court has denied petitions for writs of certiorari in

similar situations, even where the conflict among the courts

was more fully developed. Recently, for example, in McNeil v.

Legislative Apportionment Comm’n ofN .J., 124 S. Ct. 1068

(2004), this Court denied certiorari despite the existence of a

split between the Sixth, Seventh, Ninth, and Eleventh Circuits,

and a panel of the Fifth Circuit, all of which had held that

influence-dilution claims were not cognizable under the Voting

Rights Act, and the First Circuit and a different panel of the

Fifth Circuit, which held that such claims were viable. See

Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, McNeil v. Legislative

Apportionment Comm ’n ofN.J. (No. 03-652), at 9-10.

11

Denying certiorari in this context allows this Court to delay

its review of an important matter of statutory interpretation

until the issue matures through study and is further developed

by lower courts. E.g., Durden v. California, 531 U.S. 1184

(2001) (Souter, J., dissenting from denial of certiorari)

(“[R]ulings by other courts . . . would be valuable to us in any

examination of the issue we might ultimately give it.”); Lackey

v. Texas, 514 U.S. 1045 (1995) (Stevens, J., respecting denial

of certiorari) (observing that denial of certiorari gives state and

federal courts the opportunity to study the issue further); see

also McCray v. New York, 461 U.S. 961, 963 (1983) (Opinion

of Stevens, J., joined by Blackmun & Powell, JJ., respecting

the denial of certiorari) (“In my judgment it is a sound exercise

of discretion for the Court to allow the various States to serve

as laboratories in which the issue receives further study before

it is addressed by this Court.”); cf. Bunting v. Mellen, 124 S. Ct.

1750,1752 (2004) (opinion of Stevens, Ginsburg & Breyer, JJ.)

(suggesting that certiorari was properly denied where apparent

conflict could be explained by factual differences between the

case at bar and facts in “conflicting” cases).

For these reasons, the instant case is not “certworthy” and

Petitioners’ request for review should be denied.

I ll

The Judgment Below Is Interlocutory And Review

At This Stage Would Be Premature.

The Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals “remand[ed] this claim

. . . for further proceedings [and] any requisite factual findings

following an appropriate evidentiary hearing.” Farrakhan v.

Washington, 338 F.3d at 1020, App. 23a. The interlocutory

nature of the court of appeals’ ruling weighs against present

review by this court. Bhd. o f Locomotive Firemen &

Enginemen v. Bangor & Aroostook R.R. Co., 389 U.S. 327,328

12

(1967) (per curiam) (“[B]ecause the Court of Appeals

remanded the case, it is not yet ripe for review by this Court.”);

see also VMI v. United States, 508 U.S. 946 (1993) (Scalia, I.,

concurring) (“We generally await final judgment in the lower

courts before exercising our certiorari jurisdiction.”).

As stated above, the Ninth Circuit never addressed the

merits of the § 2 claim in this case; it merely held that the

district court erred in excluding evidence of discrimination in

Washington’s criminal process from consideration in the

“totality of the circumstances” inquiry on summary judgment:

“We recognize [that Plaintiffs’ § 2 claim] is a difficult issue

and that it requires a searching inquiry into all factors that bear

on Plaintiffs’ claim. We, however, express no opinion on the

merits of Plaintiffs’ claim and leave that determination to the

district court in the first instance.” Farrakhan v. Washington,

338 F.3d at 1020, App. 23a. Whether the VRA can apply at all

to felon disfranchisement statutes should not be decided on a

limited record that does not reflect the ultimate practical effect

its application in Washington. Given the limited record before

this Court, and the limited number of decisions on point, this

Court should decline review of this issue in order to allow it to

develop fully through further lower court consideration.

IV

The Court Below Decided Correctly That The VRA

Applies To Felon Disfranchisement Laws And

Further Review Is Unnecessary.

The Ninth Circuit’s holding that a felon disfranchisement

challenge is cognizable under § 2 of the VRA is legally sound

and comports with the rules of statutory construction articulated

by this Court.

13

A. The Plain Meaning Of § 2 Is Unambiguous On Its

Face.

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act expressly prohibits any

“voting qualification or prerequisite to voting” that is applied

“in a manner which results in a denial or abridgement of the

right . . . to vote on account of race or color . . . .” 42 U.S.C.

§ 1973(a). As a matter of strict textual interpretation, it is

indisputable that felon disfranchisement laws fall within the

purview of § 2 as a voting “qualification” or “prerequisite.” Id.

The ordinary meaning of the key terms in the provision —

“voting qualification or prerequisite,” “any citizen” and “on

account of race or color” — supports this reading of the

statute.6 None of these terms or phrases is elusive or confusing

6 For example, the dictionary definition of “qualification” is “a

condition or standard that must be complied with (as for the

attainment of a privilege).” See WEBSTER’S NINTH NEW

Collegiate Dictionary 963 (1990). Felon disfranchisement laws,

which condition voting on being free of a felony conviction, are a

“qualification” to voting as that term is defined. Similarly, the

dictionary definition of “prerequisite” is “something that is

necessary to an end or to the carrying out of a function.” Id. at 929.

The requirement that a person not be convicted of or under state

custody for a felony in order to vote is clearly a “prerequisite” to

voting. Moreover, as citizens of the United States, Respondents

clearly have standing under § 2, which prohibits the abridgement of

“the right of any citizen . . . to vote on account of race or color,” 42

U.S.C. § 1973(a) (emphasis added). Indeed, persons with felony

convictions fall under the definition “any citizen” within the

meaning of the statute as they never cease to be citizens during any

stages of state custody, including incarceration. Finally, felon

disfranchisement laws, like any other voting qualification or

prerequisite, might result in the denial of the right to vote “on

account,” for the sake, by reason, or because of race or color. See

Webster’s Third New International Dictionary 13 (2002)

(defining the term “on account o f’).

14

in their meaning; nor are they subject to multiple reasonable

interpretations.

As is well articulated by this Court, in interpreting the

scope of a statute, courts must first discern the statute’s plain

meaning. See, e.g., Conn. N a t’l Bank v. Germain, 503 U.S.

249, 253-54 (1992); Demarest v. Manspeaker, 498 U.S. 184,

187 (1991). If the statute’s meaning is unambiguous, as is the

language o f § 2, the court should apply the law according to its

terms. United States v. Ron Pair Enters., Inc., 489 U.S. 235,

241 (1989) (holding that where “the statute's language is plain,

‘the sole function of the courts is to enforce it according to its

terms.’”) (quoting Caminetti v. United States, 242 U.S. 470,

485 (1917)). Indeed, federal courts routinely interpret § 2 on

the basis of its plain meaning. See, e.g., Campos v. City o f

Houston, 113 F.3d 544, 548 (5th Cir. 1997) (relying on the

“plain language of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act” to

demonstrate that the provision applies only to citizens); Nixon

v. Kent County, 76 F.3d 1381,1386-87 (6th Cir. 1996) (finding

that “[njothing in the clear, unambiguous language of § 2

allows or even recognizes the application of the Voting Rights

Act to coalitions . . . .”); Johnson v. DeSoto County Bd. o f

Comm’rs, 72 F.3d 1556, 1563 (11th Cir. 1996) (holding that

the “plain language of § 2 . . . requires a showing of

discriminatory results” even where there is discriminatory

intent); New Rochelle Voter Def. Fund v. City o f New Rochelle,

308 F. Supp. 2d 152, 158 (S.D.N.Y. 2003) (“Our discussion

begins, as it must, with the consideration of the plain meaning

of [Section 2 of the VRA].”); Holley v. City o f Roanoke, 162 F.

Supp. 2d 1335, 1340 (M.D. Ala. 2001) (“A plain reading of

[Section 2 of the VRA] clearly demonstrates its applicability

only to those systems in which officials are chosen through an

election.”); France v. Pataki, 71 F. Supp. 2d 317, 326

(S.D.N.Y. 1999) (“The plain language of the Voting Rights Act

makes it clear that it is only concerned with the voting practices

15

of citizens.”); Williams v. State Bd. o f Elections, 696 F. Supp.

1563, 1568-69 (N.D. 111. 1988) (holding that “[b]y its very

terms, the [Voting Rights] Act extends only to mechanisms

involved in the election of representatives” and not the

appointment of judges).

The legislative history of an unambiguous statute is not

considered by the court for purposes of interpreting the

meaning of the statute. SeeRatzlafv. United States, 510 U.S.

135,147-48(1994) (courts will “not resort to legislative history

to cloud a statutory text that is clear.”); Schick v. Schmutz (In re

Venture Mortgage Fund, L.P.), 282 F.3d 185, 188 (2d Cir.

2002) (‘“Legislative history and other tools of interpretation

may be relied upon only if the terms of the statute are

ambiguous.’”) (quoting Lee v. Bankers Trust Co., 166 F.3d

540, 544 (2d Cir. 1999)).

Moreover, even if a statute is subject to a construction that

alters the balance between federal and state powers, only where

the statute is ambiguous must courts find a plain statement

from Congress that this result was specifically intended before

adopting that construction. See, e.g., Salinas v. United States,

522 U.S. 52,60(1997); Gregory v. Ashcroft, 501 U.S. 452,470

(1991); see also Hilton v. S.C. Pub. Rys. Comm’n, 502 U.S.

197, 206 (1991) (the plain statement rule applies only to

ambiguous statutes).

Petitioners ignore entirely the plain meaning of § 2, which

on its face clearly encompasses any voting disqualification,

including one based on a felony conviction. Instead, the State

asks this Court to disregard well-settled canons of statutory

interpretation, which require an analysis of § 2 ’ s plain meaning,

and to apply the plain statement rule, which the court below

appropriately did not reach. The State relies on general

principles o f federalism and the legislative history of the VRA

as a whole — avoiding the specific text and legislative history

of §2 — to argue that the plain statement rule applies. Id.

16

This blatant misapplication of the clear tenets o f statutory

construction should not be countenanced by this Court. Indeed,

not only has this Court never elected to apply the plain

statement rule to the VRA, it affirmatively declined to apply it

to Section 2, prior to the 1982 amendments to the statute. See

City o f Rome v. United States, 446 U.S. 156, 178-80 (1980);

see also Chisom v. Roemer, 501 U.S. 380, 412 (1991) (Scalia,

J., dissenting) (“[W]e tacitly rejected a ‘plain statement’ rule as

applied to the unamended § 2 in City o f Rome v. United States

---- ”) . And, as Petitioners concede, “Congress did not change

the scope of the coverage of the VRA in 1982. Chisom v.

Roemer, 501 U.S. 380, 384 (1980 [sic: 1991]).” Pet. at 20.

B. Even Assuming The Plain Statement Rule Applies,

The Ninth Circuit Was Correct In Holding That § 2

Covers Washington’s Felon Disfranchisement Laws.

Following its own well-settled precedent of applying the

plain meaning of statutes where it is evident, this Court cannot

reach the plain statement rule in this case. However, assuming

that the plain statement rule applies,7 the Ninth Circuit was

correct in applying § 2 to Washington’s felon disfranchisement

statutes.

1. Covering Felon Disfranchisement Under

§ 2 Does Not Alter Impermissibly The

Balance Between Federal And State

Powers.

As noted above, if a statute is ambiguous and the proffered

statutory interpretation alters the balance of federal and state

powers, the Court must find a plain statement from Congress

7 Should this Court determine that the plain statement rule

applies, it should permit the court below to conduct the analysis in

the first instance.

17

that it intended this result. Assuming, arguendo, that § 2 is

ambiguous, reading § 2 to cover felon disfranchisement statutes

does not impermissibly alter the balance between state and

federal powers and, indeed, requires no further shift in the

balance of state and federal powers than that already sanctioned

by Congress and this Court.

Congress and this Court have made clear that the VRA was

enacted specifically for the purpose of enforcing and extending

the protections of the Reconstruction Amendments. See, e.g.,

Reno v. Bossier Parish Sch. Bd., 520 U.S. 471, 482 (1997).

Furthermore, it is well settled that these Reconstruction

Amendments permissibly shift the balance o f federal and state

powers to remedy racial discrimination. By extension, the

Voting Rights Act enjoys the same latitude shared by these

amendments.

In Chisom v. Roemer, which was handed down the same

day that the Court applied the plain statement rule in

determining the application of the Age Discrimination and

Employment Act to mandatory retirement laws enacted under

the Commerce Clause,8 this Court did not apply the plain

statement rule. The omission of the plain statement rule from

the Court’s analysis in Chisom, a § 2 case, implies that the

plain statement rule does not apply to legislation enforcing the

Civil War Amendments despite their interference with state

powers. Indeed, in his dissent in Chisom, Justice Scalia

acknowledged that the plain statement rule should not apply in

Section 2 cases. Chisom, 501 U.S. at 412 (“I am content to

dispense with the ‘plain statement’ rule in the present

cases . . . .”) (citation omitted).

Gregory v. Ashcroft, 501 U.S. at 470.

18

2. The Legislative History Of §§ 2 And 4

Demonstrates Congress’ Clear Intent Not

To Exclude Felon Disfranchisement

From The Reach Of § 2.

There is simply no evidence to suggest that Congress

intended to exclude felon disfranchisement from § 2’s reach.

Nothing in the text or legislative history of § 2 provides an

exception for felon disfranchisement (or any other voting

practices that may result in discrimination on account of race).

See Chisom, 501 U.S. at 392 (“Section 2 protects] the right to

vote, and it d[oes] so without making any distinctions . . . .”).

For the same reason that § 2’s plain meaning precludes

application o f the plain statement rule, see supra pp. 13-16,

Respondents submit that the text of the statute itself is evidence

of Congress’ intent that § 2 extend to all voting practices,

including voting qualifications based on a felony conviction.

Indeed, Congress intended § 2 to have nationwide coverage and

to be construed broadly to include all qualifications,

prerequisites, standards, practices or procedures that had the

purpose or the effect of discriminating on account of race. See,

e.g., Allen v. State Bd. o f Elections, 393 U.S. 544, 565-66

(1969) ( “The [Voting Rights] Act gives a broad interpretation

to the right to vote . . . .”).

Moreover, rules of statutory construction do not require

Congress to provide a “laundry list” o f statutory application.

Moskal v. United States, 498 U.S. 103, 111 (1990) (applying

plain meaning of statute, rejecting the contention that “every

permissible application of a statute [must] be expressly referred

to in its legislative history”); see also Pa. Dept, o f Corrs. v.

Yeskey, 524 U.S. at 212 (1998) (“[T]he fact that a statute can be

‘applied in situations not expressly anticipated by Congress

does not demonstrate ambiguity. It demonstrates breadth.’”)

(quoting Sedima, S.P.R.L. v. Imrex Co., 473 U.S. 479, 499

(1985)); Circuit City Stores, Inc. v. Adams, 532 U.S. 105, 119

19

(2001); see also Chisom, 501 U.S. at 396 (breadth of statutory

language [“elect representatives of their choice”], absence of

statutory language expressly excluding judges from coverage of

section, and lack of any statements in legislative history

regarding exclusion of judicial elections, together foreclose any

interpretation of statute as not applying to judicial elections)

(emphasis added).

To the extent that Congress expressly refers to felon

disfranchisement in the text and legislative history of the VRA

at all, the statutory language and legislative history demonstrate

that when Congress intends to exclude felon disfranchisement

from the coverage of the Act, it does so plainly. Specifically,

§ 4 of the Voting Rights Act,9 in which Congress explicitly

excluded felon disenfranchisement laws from the definition of

“tests or devices,” cannot be read also to exclude felon

disfranchisement from the reach of § 2. The exclusion of felon

disenfranchisement under § 4 does not authorize states to use

felon disfranchisement as a mechanism to discriminate in

voting. Such a result would be antithetical to the purposes of

the Voting Rights Act that have been identified both in its

legislative history and by this Court. Rather, the exception

under § 4 allows states to adopt and implement felon

disfranchisement laws only so long as these laws are not

applied in a manner that is intentionally discriminatory or that

results in discrimination, in which case the laws would fall

within the purview of §2.

There is no canon of statutory construction that would

support exporting the legislative intent behind one statutory

provision to another. See, e.g., In t’l Bhd. o f Teamsters v.

9 Section 4(a) and 4(b) of the VRA, 42 U.S.C. §§ 1973b(a), (b),

establish criteria to identify jurisdictions within which literacy tests

and other devices that had been used as prerequisites to voting may

be suspended, and that also are subject to the preclearance

requirements of § 5 of the Act, 42 U.S.C. § 1973c.

20

United States, 431 U.S. 324, 354n.39 (1977) (holding that the

legislative history of a statutory provision not at bar is “entitled

to little if any weight”); see also Russello v. United States, 464

U.S. 16, 23 (1983) (“We refrain from concluding here that the

differing language in the two subsections has the same meaning

in each. We would not presume to ascribe this difference to a

simple mistake in draftsmanship.”). Sections 2 and 4 are each

substantively unique and neither their texts nor their legislative

histories are interchangeable.10

C. Application Of § 2 Of The Voting Rights Act To

Washington State's Felon Disfranchisement Scheme

Is Entirely Consistent With This Court's Ruling In

Richardson v. Ramirez.

Respondents’ VRA challenge to Washington’s felon

disfranchisement scheme is neither precluded by, nor

inconsistent with, this Court’s decision in Richardson v.

Ramirez, 418 U.S. 24 (1974). Richardson did not hold that

felon disfranchisement laws could not be challenged under

other provisions of federal and state law that do not directly

conflict with § 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment o f the United

States Constitution. Instead, this Court left open the possibility

for alternative challenges to felon disfranchisement, especially

where there is evidence of discrimination. See generally

Hunter v. Underwood, 471 U.S. 222 (1985).

10As noted supra note 9, § 4 establishes criteria for identifying

jurisdictions subject to the preclearance requirement of § 5. Those

criteria have nothing to do with § 2. This Court has “consistently

understood these sections [§§ 2 and 5] to combat different evils and,

accordingly, to impose very different duties upon the States, see

Holder v. Hall, 512 U.S. 874, 883 (1994) (plurality opinion) (noting

how the two sections ‘differ in structure, purpose, and

application’) . ” Reno v. Bossier Parish Sch. Bd., 520 U.S. at

477.

21

In Richardson, this Court examined the particular question

of whether the Equal Protection Clause of § 1 of the Fourteenth

Amendment prohibited California’s felon disfranchisement

scheme in light of § 2 of the same Amendment, which appeared

to sanction such laws. Richardson, 418 U.S. at 27. This Court

held that § 2 of the Fourteenth Amendment permits states to

exclude convicted felons from the franchise, notwithstanding

§ l ’s requirement that “[n]o state shall. . . deny to any person

within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” U.S.

Const, amend. XIV, § 1. See Richardson, 418 U.S. at 54.

However, in Hunter, nearly a decade after deciding Richardson,

this Court found that Alabama enacted its felon

disfranchisement provision with discriminatory intent and,

therefore, in violation of the Equal Protection Clause. The

Court held that § 2’s authorization of state disfranchisement

laws did not permit purposeful discrimination. Hunter, 471

U.S. at 233. Thus, Richardson is not the last word on

constitutional challenges to felon disfranchisement provisions.

Moreover, Richardson did not address the issue raised in

this case: whether the Voting Rights Act can be used to

challenge a state’s felon disfranchisement laws that result in the

denial o f the right to vote on account of race or color.

Accordingly, Richardson does not and, as a matter of stare

decisis, cannot close the door on Respondents’ challenge to

Washington’s felon disfranchisement laws.

Indeed, the VRA challenge to felon disfranchisement laws

is substantively different than the challenge brought in

Richardson because it seeks to address racially discriminatory

criminal disfranchisement. Although in Richardson this Court

held that states may deprive felons of the right to vote without

necessarily violating the Fourteenth Amendment, Richardson,

418 U.S. at 54-55, “when felon disenfranchisement results in

denial o f the right to vote or vote dilution on account o f race or

color, Section 2 affords disenfranchised felons the means to

22

seek redress.” Farrakhan v. Washington, 338 F.3d at 1016,

App. 14a; see also Wesley v. Collins, 791 F.2d at 1259-61

(assuming without deciding that § 2 applied to Tennessee’s

felon disfranchisement statute before holding that the statute

did not violate the VRA).

This is precisely what Respondents here seek to

demonstrate— that Washington State ’ s felon disfranchisement

scheme constitutes an improper race-based vote denial in

violation of § 2. This claim is simply not inconsistent with nor

foreclosed by Richardson.

23

Conclusion

For the foregoing reasons, the petition for a writ of

certiorari should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

* Lawrence A. Weiser

University Legal

Assistance

Gonzaga University

School of Law

P.O. Box 3528

721 North Cincinnati Street

Spokane, WA 99220-3528

(509) 323-5791

Dennis C. Cronin

Law Office of D.C.

Cronin

1708 West Mission Avenue

Spokane, WA 99201

(509) 328-5600

* Counsel o f Record

Theodore M. Shaw

Director-Counsel

Norman J. Chachkin

Janai S. Nelson

Ryan P. Haygood

NAACP Legal Defense

And Educational Fund,

Inc.

99 Hudson Street, Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013-2897

(212) 965-2200

Jason T. Vail

401 Second Avenue South,

Suite 407

Seattle, WA 98104

(206) 464-1519

Attorneys fo r Respondents