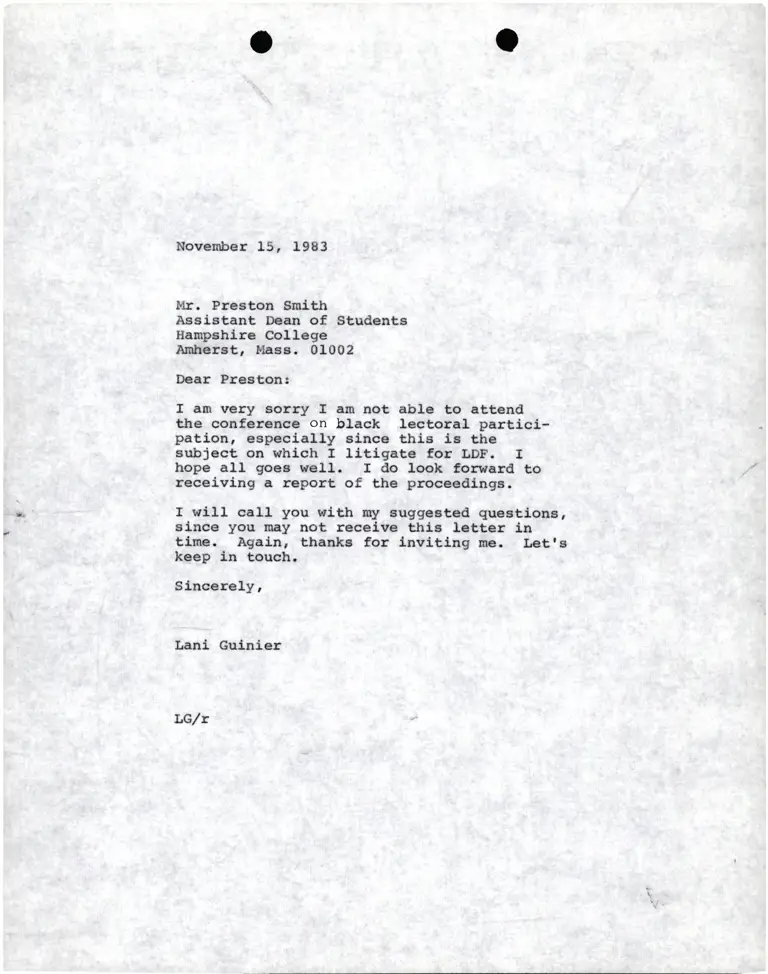

Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Preston Smith (Assistant Dean, Hampshire College)

Correspondence

November 15, 1983

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Preston Smith (Assistant Dean, Hampshire College), 1983. f6242be6-e492-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/52d48487-8d6c-4614-9dfb-9c5255c3294b/correspondence-from-lani-guinier-to-preston-smith-assistant-dean-hampshire-college. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Novcmber 15, 1983

!lr. Prceton Snlth

Asgigtant Doan of Students

Hanpahirc College

Anlrcrst, I{ass. 01002

Dcar Pregton:

I am very aorry I am not able to attend

the confCronee on black lcctoral partlcl-

patlon, eepccl.ally slnce thls le the

subJcct on whlch I lltlgatc for LDF. I

hope all goos well. I do look fomard to

recelvlng a report of the procecdlngs.

::-A ' I wtII call you wlttr Ey suggsstcd questlona,

n 8l.,nce you mty not rccelvc thle letter ln

tfunc. AgaLn, thankr for lnvltlng nc. Iotte' ksep tn touch.

Slncerely,

i

Lanl GuLnier

LG/r

oo