Sweatt v. Painter Petitioner's Reply Brief to Respondent's Brief in Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1948

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sweatt v. Painter Petitioner's Reply Brief to Respondent's Brief in Opposition to Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1948. c140489d-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/52d6a55a-5cc9-4bd6-8d5d-1a0200a18896/sweatt-v-painter-petitioners-reply-brief-to-respondents-brief-in-opposition-to-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

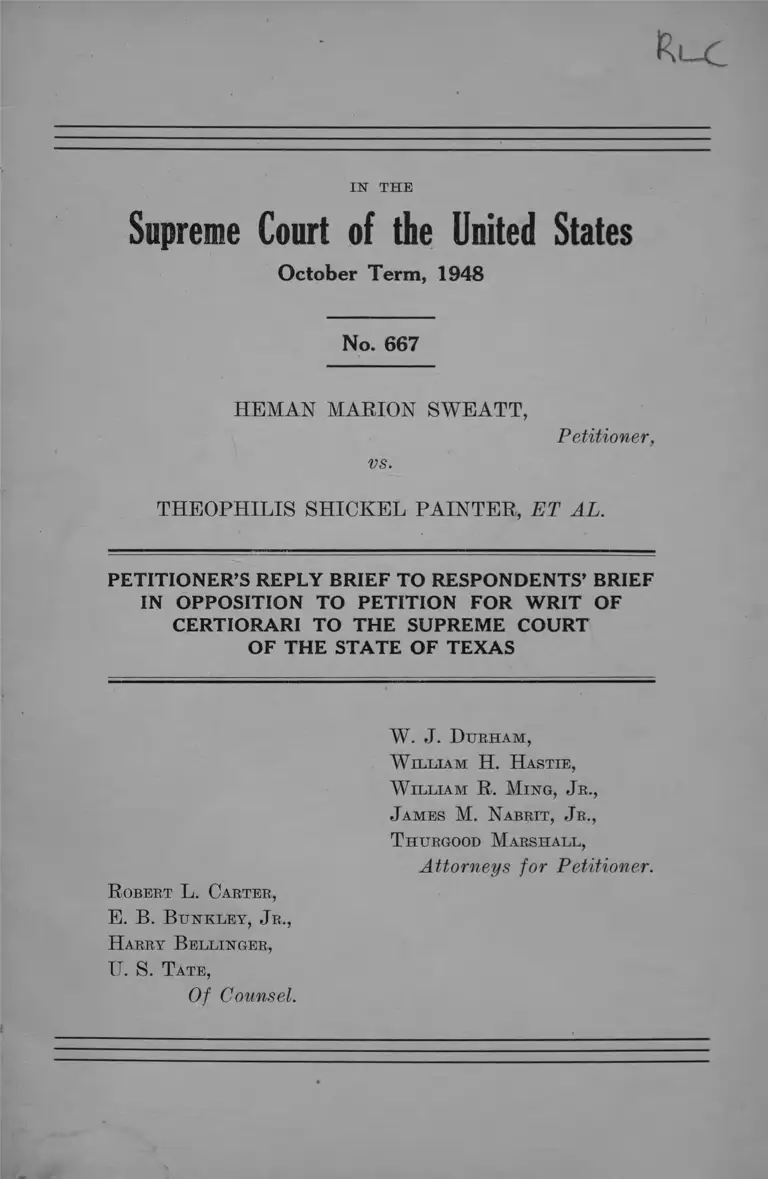

IN ' T H E

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1948

No. 667

HEMAN MARION SWEATT,

vs.

Petitioner,

THEOPHILIS SHICKEL PAINTER, ET AL.

PETITIONER’S REPLY BRIEF TO RESPONDENTS’ BRIEF

IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION FOR WRIT OF

CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE STATE OF TEXAS

W . J . D urham ,

W illiam H. H astie,

W illiam R . M ing , J r .,

J ames M. N abrit, J r.,

T hurgood M arshall,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

R obert L. Carter,

E . B . B u n kley , J r .,

H arry B ellinger,

U. S. T ate,

Of Counsel.

IN TH E

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1948

No. 667

H eman M arion S weatt,

Petitioner,

vs.

T heophilis S hickel P ainter, et al.

REPLY BRIEF FOR PETITIONER.

The brief for the respondents in opposition to the peti

tion for writ of certiorari filed herein is based upon two

main points. It is claimed that the “ separate but equal”

doctrine first advanced in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson,

163 U. S. 537, has not only been uncontroverted by later de

cisions of this Court, but is controlling in this case to the

extent of precluding the petitioner from challenging the

validity of the segregation statutes of the State of Texas

as applied to this case. This argument is followed by the

contention that the only issue to be determined is the

question of a comparison of the physical facilities of the

two law schools.

The record in this case presents to this Court for the

first time, the issue of the validity of state segregation stat

utes as applied to a Negro student seeking a legal educa

tion. The record in this case similarly presents for the

first time, expert testimony which established the unrea

sonableness of racial classifications as applied to graduate

and professional education.

2

I.

Under the theory advanced by the respondents, the states

can with impunity, use race alone as the basis for classifi

cation for governmental purposes. Respondents further

claim that such racial classifications cannot be challenged

under any circumstances. The theory also carries with it

the proposition that the effect of the enforced segregation

of one racial group of law students is not a factor to be

considered in deciding whether equal facilities are offered

within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment.1 If this

position is correct, then all state statutes enforcing racial

segregation in governmental functions are beyond challenge.

The right to be free from racial discrimination is one

of the most important guaranties of personal freedom which

our Constitution secures. This right cannot he protected

by the use of a formula which seeks to evade rather than

enforce equal protection. The petition for certiorari and

brief in support thereof shows that later decisions of this

Court have all but expressly overruled Plessy v. Ferguson

and have consistently repudiated the ratio decedendi on

which the separate but equal doctrine rests. Our position

in this case holds that the racial discrimination inherent in

the separate but equal doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson is in

the same position as was the doctrine of judicial fact of

Crowell v. Benson in the case of Estep v. United States

where Mr. Justice F rankfurter stated: “ In view of the

criticism which that doctrine as sponsored by Crowell v.

Benson, 285 U. S. 22, 76 L. ed. 598, 52 8. Ct. 285, brought

forth and of the attritions of that case through later de

1 “ Prior to the trial, the power of the State to classify, and the

reasonableness of the classification as applied in this case, had been

settled as a matter of law by this Court. Based thereon, evidence on

the point was properly limited by the trial court.” Point Three of

Respondents’ Brief, page 55.

3

cisions, one had supposed that the doctrine had earned a

deserved repose.” (337 U. S. 114, 142.)

On the other hand, respondents assert that the decisions

of later cases including the Gaines case, 305 U. S. 337, the

Sipuel case, 332 U. S. 631, and the Fisher case, 333 U. S. 147,

have reemphasized the separate but equal doctrine. The

validity of the segregation statutes of Missouri were not in

issue in the Gaines case. In the Sipuel-Fisher case, this

Court made it clear that the petition for certiorari in that

case “ did not present the issue where a state may not

satisfy the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment by establishing a separate law school for Negroes” .

The case was returned to the Oklahoma District Court

where the issue was clearly raised and evidence was pro

duced by experts, including recognized leaders in the field

of legal education from all sections of the country, who gave

their reasons why it is impossible for a Negro to obtain an

education in a separate law school equal to that available

in the regular law school. While this case was on appeal

to the Supreme Court of Oklahoma, Mrs. Fisher was ad

mitted to the law school of the University of Oklahoma and

the appeal was dismissed as being moot.2

Respondents in their brief in this Court for the first time

make an effort to show a basis for the racial classification

in this case. In the development of the third point of re

spondents’ brief, emphasis is placed upon such extraneous

matters as the “ Report of the State-Wide Survey of Pub

lic Opinion” of January 26, 1947. The inconclusiveness of

such matters is emphasized by the reaction of the student

body of the University of Texas as exemplified by recent

2 A certified copy of the transcript of record of the Retrial of this

case has been deposited with the Clerk of the Court.

4

articles appearing in the campus newspaper of the Uni

versity of Texas.3

II.

Point two of respondents’ brief raises the procedural

question brought about by their theory of the meaning of

the equal protection of the laws clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. This point is:

“ The fact question of whether Petitioner was

offered equal facilities is not properly before this

Court because Petitioner did not present it to the

Texas appellate courts for review. But assuming

the issue to be properly before the Court, there is

ample evidence to support the trial court’s findings

of fact and judgment.”

Petitioner filed his exceptions to the findings and judg

ment of the trial court (R. 441). On appeal to the Court

of Civil Appeals of Texas, petitioner included the follow

ing point:

“ The error of the Court in holding that the pro

posal of the State to establish a racially segregated

law school afforded the equality required by the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States and thus justi

3 A copy of the latest reaction to the admission of qualified Negroes

to the professional schools of the University of Texas is set forth in

the Appendix.

5

fied the denial of appellant’s petition for admission

to the law school of the University of Texas.” 4

This point was preserved in the motion for rehearing

in the Court of Civil Appeals (Points IV and VII, R. 462-

463); in application to Supreme Court of Texas for a writ

of error (Points IV and V, Respondents’ Brief, p. 107);

and in the motion for rehearing in the Supreme Court of

Texas (Points IV and V, R. 469).

The issue in this case was properly raised and has been

preserved throughout this litigation. Petitioner, believing

that this is a question of great public importance, has made

every effort to present as complete a record as is legally

possible. Respondents’ brief demonstrates an unwillingness

to have these issues determined.

Conclusion.

Access to public education is vital to our democratic way

of life. Legal education is training for service to the state.

Implicit in the meaning of democracy, is that its rights and

obligations apply to all citizens without regard to race,

color, creed or national origin. The petition for certiorari

and brief in support thereof and respondents’ brief in op

position thereto, when read together establish the over

whelming importance and significance of the issues raised

in this case.

4 Rule 418— Rules Civil Procedure of Texas provides that: “ Such

points will be sufficient if they direct the attention of the Court to the

error relied upon.”

6

W herefore, it is respectfu lly submitted that the peti

tion fo r w rit o f certiorari .to rev iew the judgm ent o f the

court below , should be granted.

R obert L. Carter,

E . B . B e r k l e y , J r.,

H arry B ellinger,

U. S. T ate,

Of Counsel.

W . J. D u rham ,

W illiam H . H astie,

W illiam R, M ing , J r .,

J ames M. N abrit, J r .,

T hurgood M arshall,

Attorneys for Petitioner.

7

Appendix.

D aily T exan— September 18, 1949

M ask B atterson—

STUDENT BAENETT GLADLY WELCOMED

There hasn’t been much said about it one way or the

other, but a big step toward putting an end to one of Texas’s

most vicious evils is being taken in Galveston this week.

About the same time students here at the University

start moving into classrooms, a 23-year-old man from

Austin will go to his first classes at the medical branch at

Galveston. His previous grades will compare favorably

with those of any other student at the school, he will study

just as hard as anyone else there this fall, and on the whole

he would probably be a good example of an average medical

student, except for one thing.

Herman Barnett, the student, is a Negro.

It ’s true that he will be there only on a temporary basis,

but the fact remains that Barnett is the first of his race to

finally make it into the same Texas classrooms as his fellow

citizens. And no matter how he got there, it’s a big step

in a state abounding in superstition on the subject of races.

Later, non-segregation in education is going to spread

until Negroes go to school here on Forty Acres.

And still later, Negroes will enter Texas high schools

and grammar schools.

This won’t come about by any sudden enveloping feeling

of liberalism on the part of Texans as a whole, bin will

evolve simply through financial necessity. Texas can’t

8

afford to maintain equal and separate institutions for its

Negro population, and eventually it will have to drop the

barriers.

What’s more, there won’t he any riots. On the contrary,

we think that when the time comes, students who don’t

already see it will realize that capability doesn’t depend

on skin color, and discover that Negroes will hit the honor

rolls in the same ratio as the white students.

They’ll learn to sit down at the same tables with Negroes

over at the Commons, and one day they’ll use the same

knives and forks that fed fellow Negro students the day

before.

In spite of what they’ve been taught by superstitious

parents, they’ll find out that all of this won’t contaminate

them, and that Negroes are humans, with the same indi

vidual faults oi; merits that humans bear.

Higher institutions of learning are the logical places

for segregation to begin its wilting process. Students are

supposed to be on the whole of a higher mental caliber, and

whether they really are or not, the fact remains that they

at least have more of a chance to sharpen their reasoning

processes enough to whittle down discrimination based on a

medieval-like their subconscious.

In spite of what a lot of the more fiery brand of liberals

seem to think, many white people simply can’t help having

the feelings they have on the subject of race. They have

been raised to believe in their superiority, and even when

their reasoning protests against it, they still have a hard

time getting things straight in their subconscious.

e don't believe many people are purposely vicious in

their attitudes, but it amounts to the same thing as far as

the Negro is concerned. All of this is what makes it a

9

problem that will take time, patience, and a working abun

dance of common sense to solve.

The Galveston branch is lucky in getting a student like

Barnett, just as his race is fortunate in having a representa

tive of his caliber. Barnett is an honor graduate from

Samuel Huston College, and he was an Air Corps officer

during the war.

He was one of thirty-five Negroes who asked admittance

to the University graduate school, the dental school at

Houston, and the Galveston medical branch last fall. At the

time, they were denied admittance.

Until someone shows us differently, we think that

Barnett will come out all right at the Isle branch.

Lawyeks Press, I nc., 165 William St„ N. Y. C. 7 ; ’Phone: BEekman 3-2300