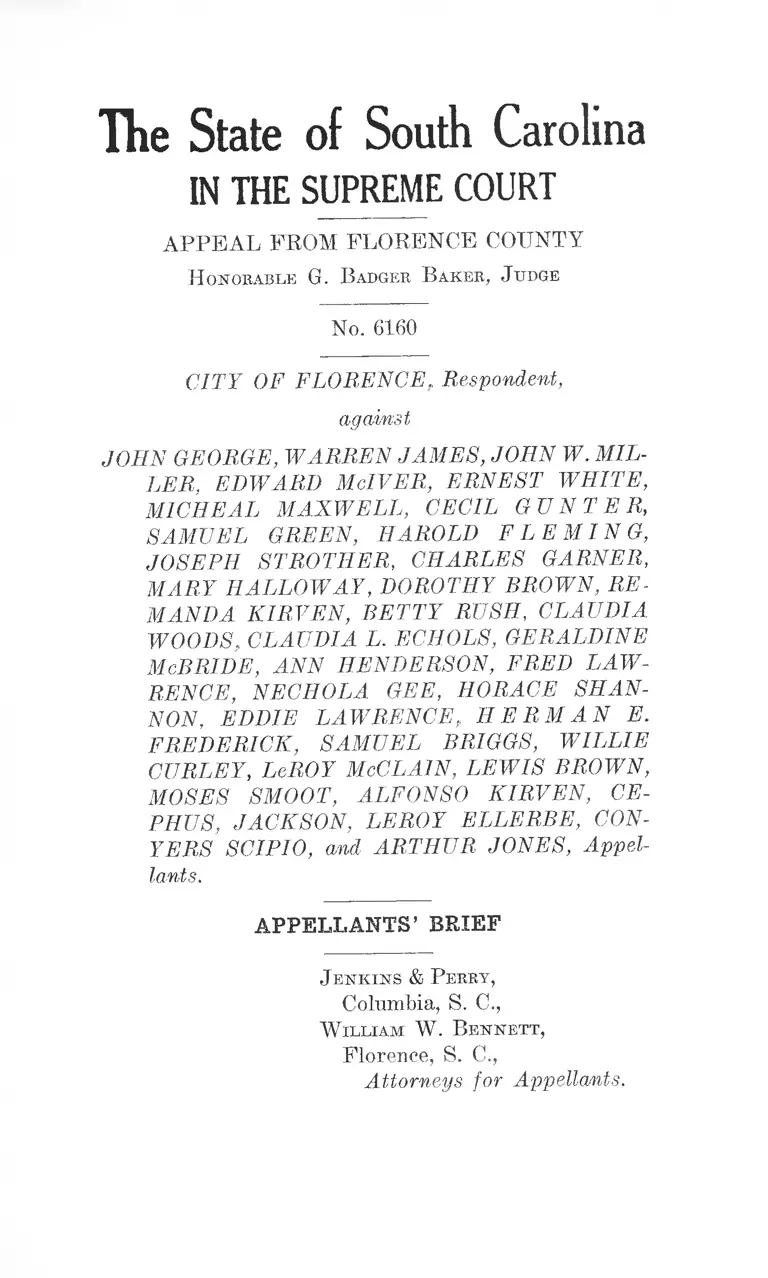

City of Florence v. George Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. City of Florence v. George Appellants' Brief, 1962. 8279bb35-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/52d9caec-dc0e-4805-a14f-d893fd6561e4/city-of-florence-v-george-appellants-brief. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

The State of South Carolina

IN THE SUPREME COURT

APPEAL FROM FLORENCE COUNTY

H onorable G. B adger B ak er , J udge

No. 6160

CITY OF FLORENCE., Respondent,

against

JOHN GEORGE, WARREN JAMES, JOHN W. MIL

LER, EDWARD McIVER, ERNEST WHITE,

MICIIEAL MAXWELL, CECIL G U N T E R ,

SAMUEL GREEN, HAROLD F L E M I N G ,

JOSEPH STROTHER, CHARLES GARNER,

MARY HALLOWAY, DOROTHY BROWN, RE-

MAN DA K1RVEN, BETTY RUSH, CLAUDIA

WOODS, CLAUDIA L. ECHOLS, GERALDINE

McBRIDE, ANN HENDERSON, FRED LAW

RENCE, NECHOLA GEE, HORACE SHAN

NON, EDDIE LAWRENCE, H E R M A N E.

FREDERICK, SAMUEL BRIGGS, WILLIE

CURLEY, LeROY McCLAIN, LEWIS BROWN,

MOSES SMOOT, ALFONSO KIRVEN, CE-

PFIUS, JACKSON, LEROY ELLERBE, CON

YERS SCIPIO, and ARTHUR JONES, Appel

lants.

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

J e n k in s & P erry ,

Columbia, S. C.,

W il lia m W . B e n n e t t ,

Florence, S. C.,

Attorneys for Appellants.

INDEX

P age

Questions Involved ................................................ 1

Statement .............................................................. 2

Argument:

Question I ....................................................... 2

Question II ..................................................... 8

Conclusion ............................................................... 10

QUESTIONS INVOLVED

I

Is Article 5, Section 47, Ordinances of the City of

Florence in violation of Article I, Sections 4 and 5,

Constitution of the State of South Carolina! (Excep

tion 3.)

II

Is Article 5, Section 47, Ordinances of the City of

Florence unconstitutional within the meaning of the

Constitution of the United States of America! (Ex

ception 4.)

2 SUPREME COURT____

City of Florence v. George et al.

STATEMENT

Appellants, numbering thirty-four (34) all Negroes,

were at the time of their arrest high school students.

They were arrested on March 4, 1960, charged with

violating Article 5, Section 47, Ordinances of the City

of Florence, in that they staged a parade upon the pub

lic streets of Florence without first obtaining a permit

therefor from the Chief of Police of that City.

Appellants were tried before City Recorder G. C.

McDonald, without a jury, on April 20, 1960. The Re

corder found all appellants guilty as charged and sen

tenced each to the payment of a fine of thirty ($30.00)

dollars or to serve thirty (30) days in jail.

Thereafter, an appeal of the Recorder’s findings,

judgment and sentence was argued before Honorable

G. Badger Baker, Resident Judge, Twelfth Judicial

Circuit. Judge Baker, on January 5, 1962, issued an

Order affirming the judgment of the Recorder’s Court.

Notice of Intention to Appeal to the Supreme Court

of South Carolina was timely served upon the City At

torney for Florence.

ARGUMENT

Question I

Is Article 5, Section 47, Ordinances of the City of

Florence in violation of Article I, Sections 4 and 5,

Constitution of the State of South Carolinaf (Excep

tion 3.)

Article 5, Section 47, Ordinances of the City of Flor

ence, for the violation of which appellants stand con

victed, is as follows:

“No funeral procession, or parade, excepting,

the forces of the United States Army or Navy, the

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Florence County

3

military forces of this State, and the forces of the

police and fire departments shall occupy, march or

proceed along any street except in accordance with

a permit issued by the chief of police and such

other regulations as are set forth in this Code

which may apply.

A funeral composed of a procession of vehicles

shall be identified as such by the display upon the

outside of each vehicle of a pennant of a type des

ignated by the traffic division of the police depart

ment.”

The record shows that appellants formed as a group

in Trinity Baptist Church and proceeded to walk east

on Darlington Street to Dargan Street, then south on

Dargan Street to the point of arrest, all in the City of

Florence (Tr. p. 103, ff. 410-412). Testimony showed

that various members of the group carried placards

containing slogans (Tr. p. 93, ff. 369-383). Over objec

tion of counsel for appellants, the Recorder refused to

allow testimony regarding the purpose and meaning

of the writing on the placards (Tr. p. 88, ff. 349-360;

p. 97, ff. 385-389).

“The right of the people by organization to co

operate in a common effort and by a public demon

stration or parade to attempt to influence public

opinion in a peaceable manner and for a lawful

purpose is regarded as among the fundamental

rights of citizens. Shields v. State (Wis. 1925), 204

N. W. 486, 40 A. L. R. 954; Chicago v. Trotter

(1891), 136 111. 430, 26 N. E. 359. Various Courts

have spoken of this right as existing immemori-

ally. Certainly it has been given official sanction

and recognition in the English Common law (see

Beatty v. Gillbanks (1882), L. R. 9 Q. B. Div.

(Eng.) 308), by a substantial number of the Su-

4 SUPREME COURT _

City of Florence v. George et al.

preme Courts of the several states (State ex rel.

Garrabad v. Dering (1893), 84 Wis. 585, 36 Am.

St. Rep. 948, 54 N. W. 1104; Anderson v. Welling

ton (1888), 40 Kans. 173, 19 Pac. 719; and State

v. Hughes (1875), 72 N. C. 25), and by the United

States Supreme Court (77. S. v. Cruishank, 92 U.

S. 542, 552, 23 L. Ed. 588; Hague v. Committee for

Industrial Organization, 307 U. S. 496, 513, 83 L.

Ed. 1425; Schneider v. Irvington, 308 U. S. 147,

84 L. Ed. 155; Thronhill v. Alabama,,, 310 U. S. 88,

84 L. Ed. 1093).”

In Anderson v. Wellington, 40 Kans. 173, 19 Pac.

719, the court said:

“The right of the people * * * by organization

to cooperate in a common effort and by a public

demonstration or parade, to influence public opin

ion and impress their strength upon the public

mind, and to march upon the public streets of the

cities * * * with * * * banners * * * is too firmly

established and has been too often exercised to be

now questioned, or to be made the basis of an ordi

nance forbidding same # * *"

The Supreme Court of Michigan, In re Frazee, 63

Mich. 396, 30 N. W. 72, construing an ordinance pro

hibiting parades upon the public streets without first

obtaining consent of the mayer or council of the city,

held the ordinance unreasonable and invalid in that it

suppressed what was perfectly lawful conduct and left

the power of permitting or restraining processions to

unregulated official discretion. (Italics added.)

In re Frazee was cited with approval by this Court

in Schloss Poster Advertising Co. v. City of Bock Hill,

190 S. C. 92, 2 S. E. (2d) 392, a case dealing with an

ordinance prohibiting the erection of a billboard fac-

SUPREME COURT 5

Appeal from Florence County

ing on any public street without first obtaining a per

mit to do so from the city council. Mr. Justice Fish-

burne, speaking for an unanimous Court, said:

“It seems to us clear upon authority and reason

that if an ordinance is passed by a municipal cor

poration, which upon its face restricts the right or

dominion which the individual might otherwise

exercise over his property without question, not

according to any general or unifoi'm rule, but so

as to make the due enjoyment of his own depend

upon the arbitrary will of the governing authori

ties of the town or city, it is unconstitutional and

void, because it fails to furnish a uniform rule of

action and leaves the right of property subject to

the despotic will of city authorities who may exer

cise it so as to give exclusive profits or privileges

to particular persons. (Citing cases.)”

It is respectfully submitted that this ordinance is

null and void as violative of Article I, Sections 4 and

5, Constitution of the State of South Carolina1 in the

following particulars:

It makes peaceful enjoyment of the right to freedom

of speech and assembly by appellants and others de

siring to use the public streets of the City of Florence

contingent upon the uncontrolled will or whim of the

Chief of Police, vesting in said official the absolute

power to issue or to deny permission to exercise said

1 Article I, Section 4: “The General Assembly shall make no

law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free

exercise thereof, or abridging the freedom of speech or of the

press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble and to

petition the Government or any department thereof for a redress

of grievances.

Article I, Section 5: “The privileges and immunities of citizens

of this State and of the United States under this Constitution

shall not be abridged, nor shall any person be deprived of life,

liberty or property without due process of law, nor shall any per

son be denied the equal protection of the laws.”

6 SUPREME COURT

City of Florence v. George et al.

right. This power is made the more absolute in that

there is provided no right to a hearing or appeal from

a decision on the part of the Police Chief granting or

denying an application for a permit. Being forced to

first obtain a permit before the right can be exercised

places a prior restraint upon appellants in their en

joyment of rights to freedom of speech and assembly.

It is vague, indefinite and uncertain, setting forth no

standard by which the Chief of Police is to be governed

in deciding who shall be granted or denied a permit.

City of Darlington v. Stanley, . . . . S. C. (2d) . .. .,

122 S. E. (2d) 207, is readily distinguishable from the

instant case. The Darlington ordinance 2 as found by

this Court, is patterned after the ordinance under at

tack in Cox v. New Hampshire, 312 U. S. 569, 85 L. Ed.

1049 and in Poulos v. New Hampshire, 345 U. S. 395,

2 “Whereas, the City Council of the City of Darlington deems

it necessary for the preservation of the health, welfare and pro

tection of the citizens of the City of Darlington, also for the

preservation of the peace and dignity of said citizens, as well as

to maintain law and order, to prohibit parades and processions

within the corporate limits of the City of Darlington, without

applicants desiring to stage said parades or processions having

first applied for and secured a special permit from the City Coun

cil of the City of Darlington to use the public streets and side-

2 3 walks for said parades and processions as hereinafter provided.

“Now, therefore, be it ordered and ordained by the City Coun

cil of the City of Darlington in council assembled and by author

ity thereof:

“Section 1. That on and after the adoption and ratification of

this Ordinance, it shall be unlawful for any person or persons,

firms or organizations to stage any parade or procession in any

of the streets or in any other public places within the corporate

limits of the City of Darlington without first having applied for

and secured a special permit from the City Council to do so, ex

cepting funeral processions, the armed forces of the U. S. Army

or Navy, the military forces of this State and the force of the

police and fire departments of the City of Darlington.

“Section 2. Such application shall contain the following in

formation: the time of such proposed parade or procession, the

streets to be used, the number of persons or vehicles to be engaged

2 4 and the purpose of such parade or procession; and, upon receipt

of such application, the Mayor or City Council shall, in its dis

cretion, issue such permit subject to the public convenience and

public welfare.”

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Florence County

7

73 S. Ct. 760; and the decision of this Court in Stanley

is based upon the reasoning of Cox and Poulos.

In the Cox case the Court held the ordinance defined

as having a limited objective, that the licensing au

thority had the limited duty of considering questions

only of time, place and manner; that the licensing au

thority did not have the arbitrary power or unfettered

discretion to refuse the permit. When the New Hamp

shire statute is examined with these factors in mind,

it is apparent that it conforms to what the Court laid

down as the crucial test. First, because of the limited

questions which the licensing authority can consider,

it becomes apparent that they may not deny the per

mit altogether. Secondly, the fixing of time and place

was not an unwarranted restriction on the right of as

sembly but was designed with a reasonable purpose in

mind; namely, the giving to public authorities a notice

sufficiently far in advance so as to afford it opportu

nity for proper policing. Thirdly, the statute did not

vest arbitrary power in the licensing authority but

prescribed a definite standard to guide the issuance of

the license; namely consideration only of time, place,

and manner.

The holding in Poulos, involving the identical ordi

nance as was construed in Cox, was reached on the

basis of the decision in favor of constitutionality as

laid down in Cox. “By its construction of the ordinance

the state left to the licensing officials no discretion as

to granting permits, no power to discriminate, no con

trol over speech. There is therefore no place for nar

rowly drawn regulatory requirements or authority.

The ordinance merely calls for the adjustment of the

unrestrained exercise of religion with the reasonable

comfort and convenience of the whole city.” Poulos v.

New Hampshire, supra, at page 766.

8 SUPREME COURT

City of Florence v. George et al.

Question II

Is Article 5, Section 47, ordinances of the City of

Florence unconstitutional within the meowing of the

Constitution of the United States of America? (Excep

tion 4.)

The rights of freedom of speech and assembly,

granted to the people by the First Amendment to the

United States Constitution, are embodied in the due

process and equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth

Amendment. The Florence ordinance under which ap

pellants were convicted is unconstitutional in that, on

its face and in its application, it denys appellants the

guarantees of the Federal Constitution. The unconsti

tutionality lies in the fact that it makes the peaceful

enjoyment of the use of the public streets contingent

upon the uncontrolled will or whim of the Police Chief

of Florence, in whom is invested absolute power, with

out setting forth any standard to govern, and without

any right of hearing or appeal, to grant or deny a per

mit to use the said streets, and places a prior restraint

upon appellants in the exercise of rights of freedom

of assembly and speech.

In Poulos v. State of New Hampshire, supra. Note

11, page 766, even though reaching a contrary conclu

sion based upon a different ordinance, the following

language is quoted:

“In considering a required permit in Hague v.

C. I. 0., 307 U. S. 496, at page 502, 59 S. Ct. 954,

at page 958, 83 L. Ed.

“Mr. Justice Roberts, in considering an ordi

nance that gave the Director of Public Safety dis

cretion as to issue of park permits, wrote:

SUPREME COURT

Appeal from Florence County

9

“Wherever the title of streets and parks may

rest, they have immemorially been held in trust

for the use of the public and, time out of mind,

have been used for purposes of assembly, com

municating thoughts between citizens, and dis

cussing public questions. Such use of the streets

and public places has, from ancient times, been

a part of the privileges, immunities, rights, and

liberties of citizens. The privilege of a citizen

of the United States to use the streets and parks

for communication of views on national ques

tions may be regulated in the interest of all; it

is not absolute, but relative, and must be ex

ercised in subordination to the general comfort

and convenience, and in consonance with peace

and good order; but it must not, in the guise of

regulation, be abridged or denied.” 307 U. S. at

pages 515-516, 59 S. Ct. at page 964, 83 L. Ed.

1423.”

Again from Poulos: “See * * * Kunz v. People of

State of New York, 340 U. S. 290, 293-294, 71 S. Ct.

312, 314-315, 95 L. Ed. 280; Saia v. People of State of

New York, 334 U. S. 558, 562, 68 S. Ct. 1148, 1150, 92

L. Ed. 1574. In these cases, the ordinances were held

invalid, not because they regulated the use of the parks

for meeting and instruction, but because they left com

plete discretion to refuse the use in the hands of offi

cials. ‘The right to be heard is placed in the uncon

trolled discretion of the Chief of Police.’ 334 U. S. at

page 560, 68 S. Ct. at page 1150, 92 L. Ed. 1574. ‘(W)e

have consistently condemned licensing systems which

vest in an administrative official discretion to grant or

withhold a permit upon broad criteria unrelated to

proper regulation of public places.’ 340 U. S. at page

294, 71 S. Ct. at page 315, 95 L. Ed. 280.”

10 SUPREME COURT

City of Florence v. George et al.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons herein stated, the judgment of the

Court of General Sessions of Florence County, which

affirmed the judgment of the City Recorder of Flor

ence, should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

J e n k in s & P erry ,

Columbia, S. C.,

W il l ia m W . B e n n e t t ,

Florence, S. C.,

Attorneys for Appellants.

39