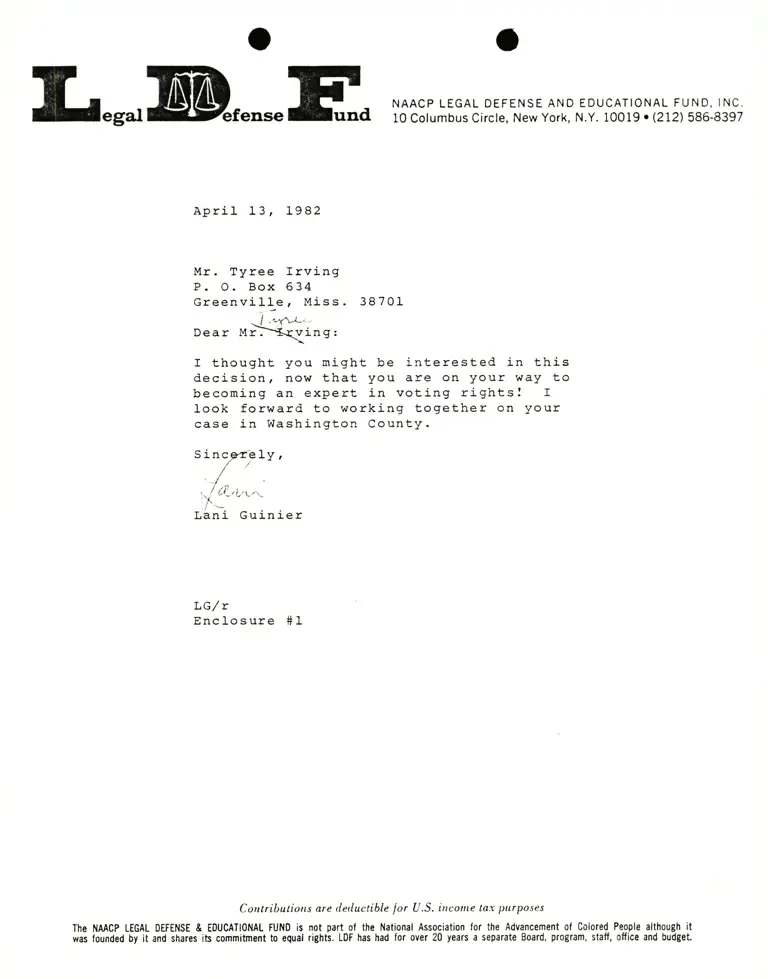

Letter from Lani Guinier to Tyree Irving RE: Recent Court Decision

Correspondence

April 13, 1982

1 page

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Letter from Lani Guinier to Tyree Irving RE: Recent Court Decision, 1982. cef79d23-e492-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/52e54494-55ab-40a4-9449-a9a2dc34cbda/letter-from-lani-guinier-to-tyree-irving-re-recent-court-decision. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Lesa,E&, H" NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

10 Columbus Circle, New York, N.Y. 10019 . (212) 586-8397

The

wits

April 13, L982

Mr. Tyree Irving

P. O. Box 634

Greenvill", Miss. 38701

- / -.rrr., .

Dear ur)-tr-qving:\ \

I thought you uright be interested in this

decision, now that you are on your way to

becoming an expert in voting rightsl I

look forward to working together on your

case in Washington County.

Slnc/yt'eLy ,

/' ./

. /rl.;.,^

i\l - - e - \

Lani Guinier

LG/ r

Enclosure #I

Contributiorts are deductible lor U.S. inconte ta:c purposes

tiAACP LEGAL 0EFEIISE & EDUCATIoNAL FUNo is not part of the l{ational Association for the Advancement of Colored People although it

founded by it and shares ib commitment to equal rights. LOF has had for over 20 years a separate Board, program, staff, office and budgel