Johnson Jr., v. Georgia Highway Express Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

November 30, 1972

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Johnson Jr., v. Georgia Highway Express Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1972. aa7d7220-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/52f72396-7b33-48ce-8978-e54f137fb694/johnson-jr-v-georgia-highway-express-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

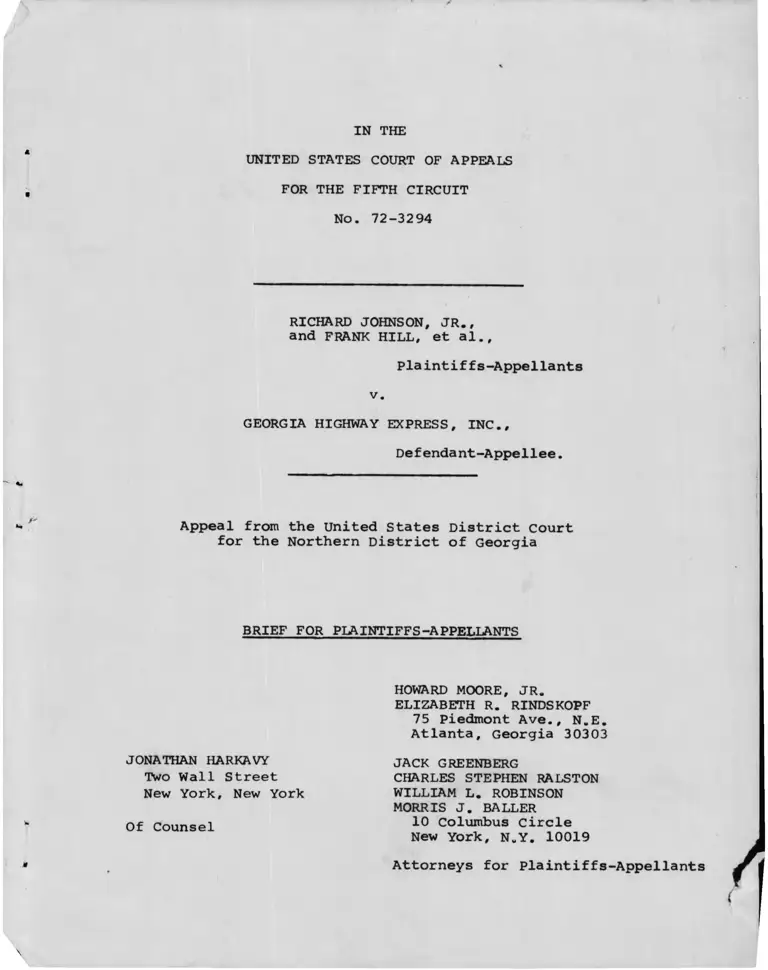

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 72-3294

RICHARD JOHNSON, JR., and FRANK HILL, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants

v.

GEORGIA HIGHWAY EXPRESS, INC.,

Defendant-Appellee.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Georgia

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

JONATHAN HARKAVY

Two Wall Street

New York, New York

Of Counsel

HOWARD MOORE, JR.

ELIZABETH R. RINDSKOPF 75 Piedmont Ave., N.E.Atlanta, Georgia 30303

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

MORRIS J. BALLER 10 Columbus Circle

New York, N.Y. 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellants

\

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 72-3294

RICHARD JOHNSON, JR. and FRANK HILL, et al.,

GEORGIA HIGHWAY EXPRESS, INC.,

Defendant-Appellee.

Appeal from the united states District court

for the Northern District of Georgia

The undersigned counsel for plaintiffs-appellants Johnson

and Hill, et al., in conformance with Local Rule 13(a),

certifies that the following listed parties have an interest

in the outcome of this case. These representations are made

in order that Judges of this Court may evaluate possible

disqualification or recusal:

1. Richard Johnson, Jr. and Frank Hill, plaintiffs.

2. The class of black employees of defendant Georgia

Highway Express, Inc., whom plaintiffs represent.

Plaintiffs-Appellants

v.

CERTIFICATE

Georgia Highway Express, Inc., defendant.3.

Page

Table of Authorities...................................ii

Statement of the Issue Presented For Review .......... v

Statement of the C a s e ...................................1

Statement of Facts.......................................5

A. The Substantive Litigation .................. 5

I n d e x

B . Evidence Pertaining to Plaintiffs'

Request for Attorney's Fees ................ 6

ARGUMENT.................................................H

I. THIS COURT HAS THE POWER TO REVIEW THE

AWARD OF ATTORNEY’S FEES BY THE COURT BELOW IN LIGHT OF PROPER PRINCIPLES GOVERN

ING SUCH AWARDS AND THE PURPOSE OF

TITLE VII.........................................12

A. This Court Can Review the Adequacy of theDistrict Court's Attorney's Fee Award . . . . 12

B . In Cases Arising Under Title VII. CounselFee Awards Must be Carefully Scrutinized

So That the Policy of That Act will be

Furthered.....................................15

1. The Purpose of the Attorney’s Fee Pro

vision of Title VII Is to Promote the

Effectiveness of Congressional Policy

Against Employment Discrimination .......... 15

2. Title VII Attorney's Fee Awards must be Sufficiently Generous to Act as a

Stimulus to Litigation...................... 18

3. To Fulfill the Congressional Policies.

Awards of Counsel Fees in Title VII CasesMust Not be Substantially Below Those

Granted for Other Types of Litigation . . . . 20

l

Page

II. THE AWARD OF COUNSEL FEES MADE IN THIS CASE WAS

NOT "REASONABLE" WITHIN THE MEANING OF

TITLE VII ...................................... 22

III. THE DISTRICT COURT'S ATTORNEY'S FEE AWARD

IS INCONSISTENT WITH GENERALLY ACCEPTED

PROFESSIONAL STANDARDS DEFINING REASONABLE

COMPENSATION FOR ATTORNEYS ..................... 28

CONCLUSION........................................... 35

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE ............................... 36

TABLE OF CASES:

B-M-G Investment Co. v. Continental/Moss Gordin,

Inc., 437 F.2d 892 (5th Cir. 1971) ................. 12

Bing v. Roadway Express, ___ F. Supp. ____

(N.D. Ga. 1972) .................................... 21

Boddie v. Connecticut, 401 U.S. 371 (1971)............ 24

Brotherhood of Railway Signalmen of America v.

Southern Railway Co., 380 F.2d 59 (4th Cir. 1967).... 28

Campbell v. Green, 112 F.2d 143 (5th Cir. 1940).... 12, 13

Clark v. American Marine Corp., 320 F. Supp. 709

(E.D. La• 1970), aff'd 437 F.2d 959

(5th Cir. 1971) ...................... 8, 16, 18, 21, 28

Cooper v. Allen, F.2d , 5 EPD f7952 (5th Cir.

1972) .............................................. 26

Culpepper v. Reynolds Metals Co., 421 F.2d 888

(5th Cir. 1970) -------------------------------- 11, 13

Electronics capital Corp. v. Shepherd, 439 F.2d 692

(5th Cir. 1971) .................................... 13

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) ......... 31

Hoffman v. Aetna Life Ins. Co., 411 F.2d 594

(5th Cir. 1969) .................................... 13

Jenkins v. United Gas Corp., 400 F.2d 28 (5th cir.

1968) ............................................... 16

Jinks v. Mays, F.2d , 4 EPD f7922 (5th Cir.

1972) ............................................... 26

ii

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc.,

417 F.2d 1122 (5th Cir. 1969)..................... 2, 5

Lea v. Cone Mills Corp., F.2d , 5 EPD 17975

(4th Cir. 1972) .................................... 24

Lee v. Southern Home Sites Co., 444 F.2d 143

(5th Cir. 1971) ................................. 16, 18

Lindy Bros. Builders v. American Radiator &

Standard Corp., 1972 CCH Trade cases f73953

(E.D. Pa. 1972) 20

Miller v. Amusement Enterprises, Inc., 426 F.2d 539(5th Cir. 1970) ......................................18

Mills v. Electric Auto-Lite Co., 396 U.S. 375

(1970) ....... ...................................16, 17

NAACP v. Allen, 340 F. Supp. 703 (M.D. Ala. 1972) .... 16

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963) ................. 19

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 401

(1968)......................................... 16, 17, 18

Peters v. Missouri-Pacific Company, F. Supp.

3 EPD <1(8274 (E.D. Tex. 1971)......................... 21

Petete v. Consolidated Freightways, 313 F. Supp. 1271

(N.D. Tex. 1970) ................................... 19

Rosenfeld v. Black, 1972 CCH Sec. Law Reports

f93635 (S.D.N.Y. 1972) ........................... 20

Rosenfeld v. Southern Pacific Co., F. Supp. ,4 FEP Cases 72 (C.D. Cal. 1971) ...................... 22

Sanders v. Russell, 401 F.2d 241 (5th Cir. 1968) ..... 19

Sims v. Amos, 340 F. Supp. 691 (M.D. Ala. 1972)....... 16

Sullivan & Cromwell v. Hudson & Manhattan Corp.

et al., N.Y.S.2d (Spec. T. Part V 1970)___ 20

Trans World Airlines, Inc. v. Hughes, 312 F. Supp.

478 (S.D.N.Y. 1970), aff'd 449 F.2d 51 (2nd Cir.1971) .............................................. 20

Page

iii

United States v. Gray, 317 F. Supp. 871 (D.R.I. 1970).. 28United States v. Gray, 317 F. Supp. 871 (D.R.I. 1970).. 28

Weeks v. Southern Bell Telephone & Telegraph Co.,

Page

STATUTES:

28 U.S.C. § 1291 ...................................... 1

28 U.S.C. § 2106 ...................................... 12

28 U.S.C., Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,

Rule 52(a) .......................................... 26

Title VII, Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000e

et seq. and § 706(k) thereof, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k).. passim

OTHER AUTHORITIES:

ABA code of Professional Ethics and Disciplinary

Rule 2-106 .................. 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34

8 American Law Reports 2nd ............................ 30

EEOC* Legislative History of Titles VII and XI ofthe Civil Rights Act of 1964 ........................ 17

Georgia Bar Reproter, April 1972 .......................31

6 Georgia State Bar Journal, No. 1 (1969) ............. 31

6 Moore, Federal Practice f54.77 ...................... 12

Shepherd's Federal Citations, Nos. 61-2 and 62-3....... 30

IV

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUE

PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

Whether, in this Title VII action, the district court

erred in awarding an amount in counsel fees that was inadequate

as a matter of law?

v

IN TIIE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 72-3294

RICHARD JOHNSON, JR.,

and FRANK HILL, et al..

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

v.

GEORGIA HIGHWAY EXPRESS, INC.,

De f enda nt-Appe11ee.

Appeal from the united States District Court

for the Northern District of Georgia

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

Statement of the case

This is an appeal from an order of the United States

District Court for the Northern District of Georgia (Atlanta

Division) awarding plaintiffs, the appellants herein, attorney's

fees in the amount of $13,500 upon a submission of 659.5 hours

of billable time spent by plaintiffs' attorneys during more

than four years of successful litigation of this landmark

case. This court nas jurisdiction of the appeal pursuant to

28 U.S.C. § 1291.

This "across-the-board" action to remedy employment

discrimination made unlawful by Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq.. was filed February 27,

1968 by plaintiff Richard Johnson, Jr. (A. 8a-13a). On

June 24, 1968, the district court entered an order holding

that the action could not be maintained as a class action,

and upholding defendant's jury demand (A. 2a). plaintiff took

an interlocutory appeal, resulting in this Court's reversing

the district court on both issues. 417 F.2d 1122 (1969). 1/

On remand, the case proceeded to trial on the merits.

After a three-day trial (Jan. 31 - Feb. 3, 1972) the district

court entered a final order on March 2, 1972, finding a wide

variety of discriminatory practices by defendant and granting

broad class relief to plaintiffs (A. 44a-56a). In that order,

the court provided that "that Court shall entertain an appli

cation for an award of attorneys' fees and costs pursuant to

Section 706(k) of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964."

(A. 56a.)

Pursuant to this ruling, plaintiffs filed a "Motion

for Award of Attorneys' Fees" in the district court on May 1,

1972 (A. 57a-78a), requesting an award of $30,145.50. In

1/ on May 12, 1970, plaintiff Frank Hill filed a separate

Title VII class action against defendant (A. 24a-27a) which

was consolidated with the Johnson action (A. 45a). immediately

prior to the trial of these actions Johnson's individual claim

was settled with the understanding that no attorney's fees

would be awarded against defendant for work done solely on

behalf of Johnson's individual claim (A. 41a-43a).

2

support of their request plaintiffs submitted: (1) a schedule

of fees based on the affidavits of counsel as to their timeexclusive of trial time

spent on this matter, in all 659.5 hours/(A. 58a); (2) six

affidavits from the five attorneys employed by plaintiffs in

this action (A. 59a-78a); (3) three exhibits showing in

chronological order the daily time spent by three of the

plaintiffs' attorneys (A. 72a, 75a, 78a); and (4) a memorandum

of law in support of the motion.

On May 4, 1972 defendant, the appellee herein, filed its

"Response to Plaintiffs' Motion for Award of Attorneys' Fees"

("Response" herein). This pleading raised a number of issues,

including, inter alia, whether the number of hours claimed to

have been spent on the case was "unreasonable" or "excessive."

The Response did not specifically enumerate the alleged excess

hours.

On June 9, 1972 the district court held a hearing on the

issue of attorney's fees at which five witnesses testified

(A. 82a-162a) and several documents were received into evidence

(A. 164a-176a). in argument at the conclusion of this hearing,

counsel for the defendant conceded that it had . . no

objection to those [fees] that would be reasonable . . and

that such reasonable fees would be $50 per hour for Messrs.

Moore and Ralston and $35 per hour for the other attorneys

(A. 160a). The district court took the entire matter under

advisement.

3

On August 8, 1972 the district court filed its order in

this matter (A. 184a-187a) and made the following findings of

fact with respect to attorney's fees:

"1. A hearing on the matter of attorneys'

fees in the primary action in this case was held,

and evidence presented by both parties, on June 9,1972.

"2. With respect to the question of attorneys'

fees in the primary action, I find that reasonable attorneys' fees, in the Atlanta, Georgia area, for

the job performed for the plaintiffs RICHARD JOHNSON,

JR. and FRANK HILL, are Thirteen Thousand Five Hundred

Dollars ($13,500.00). The above amount in this finding is based, generally, on sixty (60) man days of work

at Two Hundred Dollars ($200.00) per day, generally

considered to consist of from six (6) to seven (7)

productive hours, which amounts to Twelve Thousand

Dollars ($12,000.00), and three (3) trial days for

two attorneys at Two Hundred Fifty Dollars ($250.00) per trial day per attorney, or One Thousand Five

Hundred Dollars ($1,500.00)." (A. 184a.)

The district court made no conclusions of law with respect

to the attorney's fees issues under § 706(k) of Title VII.

The judgment of the district court on these issues is set forth

below in full:

"The Defendant GEORGIA HIGHWAY EXPRESS, INC.

shall pay to the Plaintiffs in the primary action

in the present case reasonable attorneys' fees in the amount of Thirteen Thousand Five Hundred Dollars

($13,500.00), based on what this Court has deter

mined is reasonable in this locality for the job

performed by legal counsel on behalf of the Plaintiffs.

Given the experience of counsel for the Plaintiffs

at the time these services were performed, the award

of this Court is based on sixty (60) man days at the

rate of Two Hundred Dollars ($200.00) per day, or

Twelve Thousand Dollars ($12,000.00), and three (3)

trial days for two (2) attorneys at the rate of

Two Hundred Fifty Dollars ($250.00) per day per

attorney, or One Thousand Five Hundred Dollars

($1,500.00).

4

"In making this award of reasonable attorneys'

fees to the Plaintiffs, I further note that I am

aware of the accomplishments of some of the

attorneys for the Plaintiffs. At the time when

some of these services were rendered, however, they

were rendered by attorneys who had been at the

bar for only a relatively few years, and there is

a relatively standard practice within the Atlanta,

Georgia community with respect to the age and

experience of attorneys and the compensation

involved therein." (A. 186a.)

Plaintiffs filed notice of appeal from this judgment on

September 6, 1972 (A. 188a). Defendant cross-appealed on

September 13, 1972 (A. 190a).

Statement of Facts

The documentary and testimonial evidence adduced on

the issue of attorney's fees is a memorial to the prodigious,

yet efficient, labors of five highly-skilled civil rights

attorneys in the successful litigation of a case which has

become a benchmark in the jurisprudence of Title VII.

A. The Substantive Litigation

This Court accurately described the original complaint

as an "across-the-board" attack on the whole range of racially

discriminatory employment practices of defendant Georgia

Highway Express, a large interstate trucking firm. 417 F.2d at

1124. The 1972 ruling of the district court on the merits sets

forth accurately and in detail the nature of those unlawful

practices (A. 44a-51a), sustaining plaintiffs' position with

respect to virtually every issue that was tried. The court below

5

thereupon entered a decree enjoining such practices and

ordering a variety of remedial measures to assure that they

would not be resumed or perpetuated (A. 51a-56a). Because of

the full treatment accorded the substantive issues in the

lower court's opinion, we find it unnecessary to describe

the primary litigation further here. Reference to the docket

sheets in the consolidated cases that were tried and decided

together will, however, indicate the massive effort necessary

to bring this matter to trial and successful conclusion (A.

la-7a, 19a-23a).

B. Evidence Pertaining to Plaintiffs' Request for Attorney's

Fees

Plaintiffs have requested $30,145.50 for time spent

(not including trial of the fees issue) vindicating plaintiffs'

rights and establishing important Title VII precedent as

follows (A. 58a):

303 hours x $50/hour = $15,150.00Howard Moore, Jr.

Charles S. Ralston

Gabrielle K. McDonald

Elizabeth R. Rindskopf

Morris J. Bailer

29 hours x $50/hour =

228 hours x $35/hour =

38 hours x $35/hour =

61.5 hours x $35/hour =

Trial Time of 3 days x $700/day

2/

TOTAL

1.450.00

7.980.00

1.330.00

2,135.50

$28,045.50

2.100.00

$30,145.50

2/ Mr. Ralston at $300/day and Mrs. Rindskopf and Mr. Bailer

at $200/day.

6

Plaintiffs' attorneys each submitted an affidavit supporting

the statement of time spent as shown in the foregoing itemi

zation (A. 59a-78a). These affidavits contained itemized

lists of time spent on various litigative steps, and in some

cases dates.

'The record made at the attorney's fee hearing not only

fully supports plaintiffs' request for attorney’s fees, but

also demonstrates a total lack of basis in fact for the

findings of fact of the district court.

Howard Moore, Jr., who has engaged in practice in the

Atlanta, Georgia community for a decade, testified that he is

a specialist in civil rights matters dealing with race and

has published articles on his specialty (A. 84a-86a). Mr.

Moore testified that until July 21, 1971 he spent 25 hours

on the Hill action and 278 hours on the Johnson class action.

His work on the latter covered the preparation, review and

drafting of the complaint and other pleadings, consideration

of defendant’s demand for a jury trial and motion to dismiss

the class action, the Interlocutory Appeal and extensive pre

trial discovery, including three sets of plaintiff's interro

gatories (with defendant's objections), two sets of defendant's

interrogatories and no fewer than three depositions (88a-93a).

On cross-examination the only question raised by defendant

about Mr. Moore's billable time related to one hour with

respect to the amended complaint (A. 94a-95a) and 25 hours with

respect to the drafting of plaintiffs' first interrogatories

7

(95a-97a). Apparently, defendant was content not to contest

specifically the remaining 252 hours of Mr. Moore's time, for

which Mr. Moore is requesting only $50 per hour.

Gabrielle Kirk McDonald testified as to her 2h years as

an attorney with the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund

3/("LDF" herein) in New York City and her extensive private

practice with her husband in Houston, Texas (A. 100a—103a).

Mrs. McDonald, who has been a member of the Bar for about six

years, is a specialist in Title VII litigation and maintains

an active docket of matters similar to the case at bar. During

the time she was associated with LDF, Mrs. McDonald handled

approximately 25-30 Title VII cases (A. 102a). Mrs. McDonald's

affidavit indicates that she spent a total of 228 hours on

the Johnson case, including 40 hours preparing for and success

fully arguing the Interlocutory Appeal (A. 67a—68a). Mrs.

McDonald testified that the Johnson case is ". . . probably

the most important case that I personally worked on as far as

precedent setting in the area of Title 7 [sic] . . . .

(A. 106a), and that this case of "tremendous importance"

presented extremely difficult issues of first impression which

were ultimately resolved in favor of plaintiffs and against an

effective nullification of Title VII (A. 107a). Mrs. McDonald

3/ Of course, the fact that much of plaintiffs' legal work

was performed by LDF staff attorneys can haye no bearing on

the attorney's fee question. Clark v. American Marine Corp.,

320 F. Supp. 709, 711 (E.D. La. 1970), aff'd per ̂ f x a m,437 f .2d 959 (5th Cir. 1971); Miller v. Amusement Enterprises,

Inc.. 426 F.2d 534, 538-539 (Sth ciF. 1970).

8

requested the rate of $35 per hour for her time on this

case although her normal billing rate is $50 per hour and

the minimum fee in her locality for such work is $40 per

hour (A. 109a). On cross-examination defendant did not contest

188 of the hours spent by Mrs. McDonald on the case, but

only the 40 hours she spent preparing for and arguing the

appeal to this Court (A. 114a-117a).

David cashdan (spelled "Cashton" throughout the transcript)

was a lawyer with the EEOC in Washington, D.C. for over five

years and is now a partner in a Washington, D.C. law firm

(A. 122a-123a). Mr. cashdan indicated that he had extensive

and detailed experience in the development of Title VII law

while with EEOC during the Act's early years (A. 125a-127a).

Mr. Cashdan testified as to the development of Title VII

jurisprudence and was offered as an expert witness on behalf

iof plaintiffs. He was familiar with Johnson in part because

the EEOC filed a brief amicus curiae in the interlocutory

appeal. He characterized the issues on that appeal " . . . both

as difficult . . . and very important to the work in Title 7"

(A. 130a), and rightly termed this court's decision therein

the "focal point" of class action law under Title VII (A. 130a-

131a). Mr. cashdan testified at length about the nature of

the issues litigated in this matter and further stated that

he found the attorney's fee affidavit submitted by plaintiffs

to be within the "realm of reason" (A. 134a) .

9

Michael Doyle testified on plaintiffs’ behalf that

he is a partner in the firm of Alston, Miller and Gaines in

Atlanta, Georgia and has practiced for over a decade, principally

in the area of civil litigation (A, 144a-145a). He testified

that the rates charged by lawyers in the Atlanta area vary

"from $35.00 an hour, even lower than that, depending on the

matter and the lawyer, and to, I am certain, a hundred dollars

an hour or in excess thereof." (A. 148a.) Mr. Doyle testified

that a charge of $50 an hour would be reasonable for an

experienced lawyer handling a case involving federal issues

and a federal trial with an appeal (A. 149a). on cross-

examination defendant did not question the conclusions drawn

by Mr. Doyle. Mr. Doyle further testified on redirect

examination that the law firm employed by plaintiffs enjoys

a good reputation in the Atlanta community (A. 152a).

It is important to reiterate that aside from defendant's

attempt to contest the participation of Legal Defense Fund

attorneys in this matter (the subject matter of defendant's

cross-appeal), the only hours actually put into issue by

defendant's responsive pleadings and testimonial and documentary

evidence amount to 40 hours of Mrs. McDonald's time with

respect to the interlocutory appeal and 26 hours of Mr. Moore's

time with respect to plaintiffs' first interrogatories and

amended complaint.

10

argument

rhis court, as part of its obligation ". . . to make sure

that Title VII works . . . " should ensure that in no way is

nullified the will of Congress that racial discrimination in

employment shall be eliminated from the united States. The

importance of this appeal is that it poses the question of

whether, taking account of practical realities, that will is

to be served or undermined. in this case the district court's

award of attorney's fees fails to meet any measure of

reasonableness, much less serve the purposes which Congress

intended such an award to serve. Plaintiffs respectfully

contend that if this Court sustains this factually unsupported

award of less than $20 per hour to attorneys of high repute

and experience in civil rights matters for successful work

done in this landmark case, its ruling will have a chilling

effect on the exercise of Title VII rights and will thereby

tend to foster the erosion, through neglect, of the vigilance

which Congress intended the private bar to exercise in defense

of Title VII rights.

and nri ^ 5t h ^ ir.̂ ToTo^5 Metals Company. 421 F.2d 888, 891

11

I

THIS COURT HAS THE POWER TO REVIEW

THE AWARD OF ATTORNEY'S FEES BY

THE COURT BELOW IN LIGHT OF PROPER

PRINCIPLES GOVERNING SUCH AWARDS AND

THE PURPOSES OF TITLE VII

In this part of our brief we will discuss two propositions:

that this Court generally has the power to review attorney's

fee awards, and that there are particular standards to be

applied in Title VII cases. Part II will demonstrate that the

award made below does not meet those standards.

A. This Court can Review the Adequacy of the District Court's

Attorney's Fee Award"

This Court has held generally that the determination of

what is a reasonable attorney's fee is a proper function of

an appellate court. B-M-G investment Co. v. Continental/Moss

Gordin, Inc., 437 F.2d 892, 893 (5th Cir. 1971); Campbell v. -----------

Green, 112 F.2d 143, 144 (5th Cir. 1940). Thus, in B-M-G

Investment Co., supra, this Court observed that although it

was cognizant of the role of trial court discretion in the

matter of awarding attorney's fees:

5/ This rule must, of course, be distinguished from the rule

that trial courts ordinarily have broad discretion whether or not to award attorney's fees against a party (except in cases

such as the instant one where the fees are a part of an effective

remedy or serve the ends of established policy). See generally

6 Moore, Federal Practice f54.77. The power of this Court to

determine the reasonableness of such fees and make awards

derives from its inherent equitable powers and from 28 U.S.C.

§ 2106.

12

"However, appellate courts, as trial courts,

are themselves experts as to the reasonableness

of attorneys' fees, and may, in the interest

of justice, fix the fees of counsel albeit in

disagreement on the evidence with the views of the trial court." 437 F.2d 892 at 893.(Emphasis added.)

See also, Campbell v. Green, supra at 144. under this "active"

review standard, this Court therefore can review the adequacy

of a district court's attorney's fee award based on its own

, , 6/knowledge and experience as well as on the facts of record.

In several recent cases, the Court has appealed to prefer

an "abuse of discretion" standard of review. e .£., Culpepper v.

Reynolds Metals Co.. 422 F.2d 1078, 1081 (5th Cir. 1970);

Electronics capital Corp. v. Shepherd. 439 F.2d 692 (5th cir.

1971); and especially Weeks v. Southern Bell Telephone &

Telegraph Co., ____ F.2d ____, 5 EPD f7956 (5th cir. No. 72-

1075, September 7, 1972). Nevertheless, we do not read Weeks

or the other cases as contrary to the proposition that this

Court can and should consider attorney's fee awards with an

informed and careful review. Despite Weeks' language stressing

6/ Electronics Capital Corp. v. Shepherd, 439 F.2d 692 (5th Cir. 1971) is not contrary to the settled rule allowing review

despite some inconsistent language in the per curiam opinion.

The Shepherd court apparently examined the record at length and

independently concurred with the district court. Moreover, the

court relied on Hoffman v. Aetna Life Ins. Co., 411 F.2d 594

(5th Cir. 1969) as authority for an "abuse of discretion" rule even though Hoffman stands on its own footing as a bankruptcy

case involving such special considerations as statutory standards for fees and a limited fund from which fees are granted.

13

the discretion which may be exercised by the district court,

this Court in fact closely examined the bases and reasons for

Judge Bell's award. It noted:

Judge Bell reviewed the many factors

that are properly taken into consideration

in determining a reasonable attorney's fee.

* * * *

Judge Bell thoroughly discussed the bases

for his award of attorney's fees to Mrs.

Roberts. He weighed the result obtained,

the time expended by Mrs. Roberts . . .

[expert testimony and affidavits]. Additionally,

Judge Bell considered the decision of Judge

Rubin in Clark v. American Marine Corporation

[citation omitted] I . He considered the

briefs filed in the Fifth Circuit, the record, the difficulty of the appeal, the efforts on

remand and the contingency of an attorney's fee

award.

Judge Bell . . . was fully aware of the

importance of the Weeks case.

5 EPD f7956 at pp. 6544-6545. Thus, this Court in Weeks

concluded that no abuse of discretion had been shown only

after assuring itself that the proper factors had been fully

considered by the district court and that the court’s opinion

adequately articulated the bases for the award in terms of

7/those factors.

7/ Plaintiffs believe the dissenting opinion of Judge Wisdom

Tn Weeks more properly states the law than does the majority

opinion. However, even accepting the majority's view, our

point is that Weeks does not preclude careful appellate scrutiny

here; and that in fact Weeks does not dispose of the issue as

to the adequacy of the award. See n. 14 infra.

14

The order appealed from here differs dramatically from

the Weeks award as characterized in this Court's opinion. The

District Judge here made only the sketchiest findings of fact

in handing down the award of $13,500 (A. 184a). He entered

no conclusions of law in this respect (A. 184a-5a). And in justi

fying the award, he adduced only vague, general reasons (A. 186a)

There is no indication at all that the court below considered

most of the factors referred to in the Weeks opinion, or other

factors, discussed below, that should properly have been

considered. it is one thing to review cautiously a carefully

articulated and justified basis for an award as "within

discretion.” it would be entirely different to rubber-stamp

an award that is on its face inadequate; that is, as will be

shown, contrary to both usual standards and public policy, and

that is so sparsely rationalized that this Court can only guess

at the trial judge's factual and legal conclusions. This

appeal presents the latter situation, and calls for careful

V*

scrutiny, particularly in light of the special policy considera

tions that attach to a Title VII action.

B . In Cases Arising Under Title VII, Counsel Fee Awards

Must be Carefully Scrutinized so that the Policy of that Act will be Furthered

1. The Purpose of the Attorney's Fee Provision of

Title VII Is to Promote the Effectuation of Congressional Policy-Against Employment

Discrimination.

The primary consideration in reviewing an award of fees

pursuant to Title VII is that the award must reflect its status

15

as part of the effective remedy for enforcing the Act. This

guideline has been adhered to by numerous district courts in

this circuit and has been affirmed by this Court on several

occasions. E.^., Clark v. American Marine Corp., supra y see,

Lee v. Southern Home Sites Co., supra, and Sims v. Amos, 340

F. Supp. 691, 694 (M.D. Ala. 1972). ("Indeed, under such

circumstances, the award loses much of its discretionary

character and becomes a part of the effective remedy a court

shall fashion to encourage public minded suits and to carry

Congressional policies.") Accord, NAACP v. Allen, 340 F. Supp.

703, 709 (M.D. Ala. 1972). The guideline has its genesis in

two Supreme Court decisions, in which it was held that attorney's

fees can be based on the broad principle of effectuating

Congressional policy and encouraging public interest suits—

irrespective of the good or bad faith of defendants (the

traditional touchstone of such an award in equity). Mills v.

Electric Auto-Lite Co., 396 U.S. 375 (1970); Newman v. Piggie

Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400 (1968).

It is clear that Congress intended that attorney's fees

are to be awarded as part of the effective remedies available

to the courts as a means of fostering enforcement of Title VII

by private litigants. Enforcement of rights derived from

Title VII is committed principally to the victims of discrimi-

8/

nation forbidden by the Act. Congress manifested its

8/ 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(a)- (k). See Jenkins v. United Gas

Corp., 400 F.2d 28, 32 (5th Cir. 196871

16

solicitude for Title VII beneficiaries acting as private

attorneys general in several ways (see § 706(e), 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-5(e)), most importantly by providing in § 706(k),

42 U.S.C, § 2000e—5(k), that plaintiffs should receive an

award of "reasonable" attorney's fees as part of the costs

9/allowed to them. Congress perceived that the availability

of truly reasonable awards which encourage vigorous effec

tuation of Title VII rights by the private sector, on behalf

of litigants and classes who would not, ordinarily, be able to

hire an attorney by their own means.

Of all the Title VII cases to date in this Court, the

present case best illustrates the import of the "private

attorney general" concept, and plaintiffs' attorneys should be

compensated with due regard to that principle. The action of

the individual plaintiffs resulted in the district court's

broad class ruling which will benefit many persons. Not only

did plaintiffs perform a private function in vindicating the

rights of many of their co-workers who were victimized by

racial discrimination, but more importantly, they performed

the public function of furthering the Congressional mandate

embodied in Title VII by procuring relief beneficial to the

broad public. Thus, they acted within the purposes set forth

as bases for generous compensation in Mills v. Electric Auto-

_Litje, supra, and Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, Inc.

9/ See generally, EEOC, Legislative History of Titles VII and

XI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. ("Legislative History" herein), especially pp. 3004-3007.

17

2• Title y n Attorney's Fee Awards must be

Sufficiently Generous to Act as a Stimulus to Litigation

As the Supreme court held in interpreting the identical

attorney's fee provision of Title II of the civil Rights Act

of 1964, the award must properly effectuate the purpose of the

Civil Rights Act. Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises. Inc..

390 U.S. at 401. in particular, the award must "encourage

individuals injured by racial discrimination to seek judicial

relief under [Title VII]," id. at 402; accord. Miller v.

Amusement Enterprises, Inc.. 426 F.2d 539 (5th Cir. 1970).

This Court has already recognized that, in order "to

ensure that individual litigants are willing to act as private

attorneys general to effectuate the proper purposes" of

eights laws, it has an obligation to make an award which

will further foster the enforcement of those laws by plaintiffs.

Lee v. Southern Home Sites Co., 444 F.2d 143, 148 (1971);

accord. Clark American Marine Corp.. supra. Stated another way,

the award must be generous enough so as not to deter the

vindication of Title VII rights by private attorneys general.

The minimal award allowed below runs head on into these

principles. Far from encouraging the private vindication of

personal rights and public policy, it stands as a threatening

obstacle to such efforts. we ask this Court, as lawyers

who have practiced at the bar, to consider the likelihood

that aggrieved victims of discrimination will be able to

secure effective legal representation on terms of (i) a wholly

18

contingent fee which is (ii) payable only after many years

of litigation, involving (iii) complex, novel, and technical

federal questions, and then (iv) at rates substantially below

those for which attorneys are compensated on a non-contingent

basis for routine civil matters such as domestic, probate or

contract practice. If the award below stands, it can only

signal potential Title VII advocates that they may represent

plaintiffs with the certain expectation of having to make

large financial sacrifices, even if they ultimately prevail.

Few members of the private bar may be expected tohearken to

such a forbidding call.

It cannot be over-emphasized that Title VII cannot work

and its promise will be broken if the private bar is forced

to shun Title VII cases or treat them cavalierly simply because

Title VII work would force its practitioners into bankruptcy.

This court is already well aware of the hardships civil rights

10/lawyers face in their communities. By adding potential

bankruptcy as a consideration in taking on such work this

Court would effectively nullify the role congress sought

for the private Title VII litigant. If the role of the

private litigant is effectively destroyed then enforcement of

Title VII rights will, contrary to the mandate of Congress,

be committed exclusively to the mercy of those who hold the

purse strings of the EEOC and those who have responsibility

for Title VII enforcement in the Department of Justice. Such

10/ E.-2.** Sanders v. Russell, 401 F.2d 241 (5th Cir. 1968);

and see NAACP v. Button. 371 U.S. 415, 443 (1963); Petete v.

Consolidated Freightways, 313 F. Supp. 1271 (N„D. Tex. 1970).

19

a restriction of effective Title VII enforcement to govern

mental agencies alone would flatly contravene the entire

scheme of Title VII.

3. To Fulfill the. Congressional Policies, Awards of

Counsel Fees In Title VII cases Must Not be

Substantially Below Those Granted for Other Types

of Litigation

In judging the adequacy of the award made by the district

court here, this Court should consider the generous awards which

have been accorded to prevailing parties in other forms of

civil litigation, and should not let stand a fee which would

constitute a discrimination against civil rights cases. For

example, in Lindy Bros. Builders v. American Radiator &

Standard Sanitary Corp., 1972 CCH Trade cases f73953 (E.D.

Pa. 1972), plaintiffs' counsel were awarded $1,374,655 (in

addition to $802,707 they collected out of the class recovery)

— or $215 per hour of work. See also Trans World Airlines,

Inc, v. Hughes, 312 F.Supp. 478, 485 (S.D.N.Y. 1970), aff1d

449 F.2d 51, 79 (2nd Cir. 1971) ($7,500,000 plus disburse

ments, or $128 per hour). Outside the realm of antitrust

cases, see Sullivan & Cromwell v. Hudson & Manhattan Corp.,

et al., N.Y.S. 2d (Spec. T. Part V 1970) [N.Y.

Law Journal, May 13, 1970, pp. 17-18], awarding $3,750,000

plus costs in a corporate reorganization case; and Rosenfeld

v. Black, 1972 CCH Sec. Law Reports J[93635 (S.D.N.Y. 1972),

allowing counsel fees of $250,000 in a shareholders' derivative

action, in part in reliance on the fact that "he made the law."

Apparently, the generosity of civil courts has few limits when

it comes to ordinary civil litigation not involving human rights.

It would be anomolous for this Court, or any other court, to

20

accord less significance to the vindication of human rights

than to the achievement of corporate ends.

The majority of recent considered attorney's fee decisions

in Title VII actions have indeed adhered to this principle

and awarded fees based on reasonable rates. For example, in

Clark v. American Marine Corp.. supra, the leading case on

attorney's fees in this circuit, the district court awarded,

and this Court upheld on appeal, the sum of $20,000 for 580

hours of billable time. The rate of compensation there was

$35 per hour. in Bing v. Roadway Express, Inc.. ____ F. Supp.

_____ (N.D. Ga. 1972), on remand from 444 F.2d 678 (5th Cir.

1971), the district court ultimately made an award of $22,500

for 650 claimed hours. The rate of compensation in that case

was, therefore, $35 per hour. In Peters v. Missouri Pacific

Company, ____ F. Supp. _____, 3 EPD 1(8274 (E.D. Tex. 1971),

on appeal No. ________, the district court awarded a lump sum

fee of $44,000 plus six percent interest. As noted in plaintiff's

post-trial brief, the claimed time was 490 hours and the effec

tive rate of compensation is, therefore, around $90 per hour.

Even in Weeks v. Southern Bell Telephone & Telegraph Co., which

was not a class action and did not involve any trial work by

the compensated attorney, this Court sustained an award of more

than $25 an hour for time claimed by a single practitioner.

Moreover, the Weeks court indicated that the work could have

been done there in substantially less time than claimed; thus,

the effective rate of pay is substantially in excess of the $25

21

rate. Outside this circuit, plaintiffs would note in particular

Rosenfeld v. Southern Pacific Co., ____ F. Supp. , 4 FEP

Cases 72 (C.D. cal. 1971) (award of $30,000 based on rate of

about $74 per hour).

II

THE AWARD OF COUNSEL FEES MADE

IN THIS CASE WAS NOT "REASONABLE"

WITHIN THE MEANING OF TITLE VII

In Part I of this brief we have demonstrated that this

Court has the power to review the counsel fee award entered

below. Moreover, in making that review, this Court must

carefully scrutinize the award to ensure that it complies

with special standards applicable to Title VII cases, viz.,

does the award further Congressional policy by being suffi

cient to encourage the vigorous enforcement of Title VII and

was it arrived at based on rates comparable to those applicable

in regular commercial litigation?

In order to judge the adequacy of the award it is first

necessary to analyze it in light of the undisputed record made

herein. First, it is evident that the district court's findings

and judgment are simply not supported by the evidence. Both

parties agreed as to the reasonableness of hourly charges:

$50 and $35 per hour, standard rates prevailing in the Atlanta

area for federal civil actions. The court's figures demonstrate

that the rate used was significantly less than that.

22

The court used a figure of 60 hypothetical working days

for the entire litigation of this case from its inception,

with the exception of the three days in court. At 6 or 7

hours per day this amounts to from 360 to 420 hours (the lack

of basis for reduction of the claimed hours will be discussed

below). it awarded $12,000 so that the rate charged was

at the most $33.33 and as little as $28.57 per hour. The

highest amount was too small even if it were assumed that all

work was done by the less experienced attorneys and therefore

billable at $35/hour. Of course, the evidence showed that

experienced counsel, whose services were admittedly billable

at $50/hour, did approximately one-half of the work in the

case.

As we have shown, the purpose of Title VII and the role

of attorney's fees in achieving its mandate require awards

based on rates no less than these applicable to normal

litigation. The district court apparently failed to give

any consideration to the Congressional intent implicit in

§ 706(k) when it made so meager an award in this case of so

widespread import. In the face of such plain policy con

siderations the district court's award fails to compensate

adequately the five attorneys who achieved such great success

in this litigation; therefore, the award must be set aside as

being contrary to the mandate of Congress. This Court, among

all the courts in this nation, has always stood for enforcement

of a plainly apparent Congressional mandate that discrimination

23

must end. What plaintiffs seek here is not merely an award

of money— it is a rule which will give judicial life to

11/that mandate.

Second, the district court's computation of the number of

hours necessary to litigate this complicated and important case

has no support in the record and indeed is contradicted by it.

As noted above, the court allowed a total of no more than

420 and perhaps as little as 360 hours. No reason is given

for the disallowance of from 239.5 to 299.5 of the 659.5 hours

claimed. Indeed, opposing counsel disputed only 66 of those

12/

hours.

11/ The district court's award would also, if upheld by this

Court, contravene more fundamental and less explicit policies.

First, this inadequate award would be inconsistent with the

notion that access to the courts for the vindication of human

rights must not be made to depend on the wealth of the person

seeking access. Ihe true loser in the case of an inadequate

award is not the attorney or even the profession— it is the

potential litigant who will find it increasingly difficult to

hire attorneys to vindicate his rights. Since a wealthy

potential litigant would be able to hire an attorney to assure

his rights, it is clear that the destruction of the incentive

for private attorneys to take on Title VII cases would result in a discrimination against disadvantaged potential litigants

who could not afford to hire an attorney. Such a form of discrimination in access to the courts has been condemned in civil as well as criminal cases as unconstitutional and should

not be sanctioned here. Boddie v. Connecticut, 401 U.S. 371

(1971).

12/ Forty of these hours were spent by Mrs. McDonald in

preparation for and arguing successfully the interlocutory appeal, and there is not even a suggestion in the facts that

Mrs. McDonald padded her time. As for the other 26 hours, there

is a contention that the identity between the interrogatories in

this case and another is evidence of excessive use of time.

Aside from the fact that 26 out of 659 hours is de minimis, it

can hardly be said that defendant has proved that the 26 hours

were not necessary to the case.

24

Thus, unlike the case in Weekst supra, where this Court

was skeptical of 585 hours spent only after trial of an

individual action, there is no suggestion here of any "padding"

wof time. Furthermore, there is no evidence of substantial

and unnecessary duplication in this case. Cf. Lea v. cone

Mills Corp., ____ F.2d ____, 5 EPD f797 5 (4th Cir. 1972). During

the four years of this litigation only five attorneys worked

on this matter. Mrs. McDonald worked principally on the legal

issues raised by the interlocutory appeal. Only when the

original lead attorney, Howard Moore, Jr., had to drop out

of the case did the other attorneys take part in the litigation.

Thus, instead of duplication, plaintiffs' attorneys efficiently

allocated their resources.

The district court's order makes only one other factual

point which is easily disposed of. The court says that

notwithstanding the accomplishments of plaintiffs' attorneys,

at the time such attorneys rendered their services they were

inexperienced. This "finding" is simply not true as a matter

of fact. At the time of trial Mr. Ralston had been a practicing

attorney for nearly eight years, Mrs. Rindskopf had been a

practicing attorney for nearly four years, and Mr. Bailer had

13/ we note that, although a greater amount was affirmed

there for less time spent, that award was For the appeal and

settlement of an individual claim. Here, plaintiffs won an

equally difficult appeal, and also a class action trial.

25

been a practicing attorney for over one year. Of plaintiffs'

other attorneys, Mr. Moore had over six years' experience

when he commenced this litigation, and Mrs. McDonald had

been in practice two years as a Title VII specialist when

she prosecuted the appeal herein. In light of their years

at the bar and their intensive and extensive experience in

civil rights actions these attorneys can hardly be characterized

as fresh out of law school or inexperienced, particularly in

this field.

In sum, there is no basis in fact for any of the findings

and judgments of the district court.

Plaintiffs further submit that the findings of the

district court fail to provide this Court with a sufficient

basis for a review of the district court's judgment. Plaintiffs

assert that this Court must, in the absence of detailed

findings such as in Weeks, supra, set aside the award of the

district court and either make one of its own on the basis

of this complete record, or remand with directions to enter

a more generous award based on articulated and reviewable

findings and standards. This Court has recently held that

where the district court's discretion in awarding attorney's

fees is limited by public policy considerations the district

court must "articulate specific and justifiable reasons" for

its determination. Cooper v. Allen, F.2d , 5 EPD

f 7952 (5th Cir„ 1972). Cf. Jinks v. Mays, F„2d

4 EPD f7922 (5th Cir. 1972) (impossibility of review without

findings); and Rule 52(a), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

26

This case is one in which the discretion of the district

court must be exercised within limits of supervening policy

as discussed in part I above. Congressional policy, to be

vindicated, requires that counsel fees in Title VII cases

be awarded generously. This is particularly so in a case such

as the present one, where the efforts of counsel for private

plaintiffs resulted in a seminal decision that has resulted

in making Title VII a truly effective remedy for the effective

vindication of rights. Because counsel established, in this

case, the right to seek broad class relief to the benefit of the

entire black community, they have acted as "private attorneys-

general" in the fullest sense of the term. Their efforts, and

hence those of other attorneys handling other litigation of

great public importance, must be encouraged.

Because the district court clearly did not exercise

its discretion in light of these policies, its decision

must be reversed.

27

Ill.

THE DISTRICT COURT'S ATTORNEY'S FEE AWARD

IS INCONSISTENT WITH GENERALLY ACCEPTED

PROFESSIONAL STANDARDS DEFINING REASONABLE COMPENSATION FOR ATTORNEYS.

As shown above, the award of only $13,500 as attorney's

fees violates the spirit and public policy of Title VII's

provision for "reasonable" awards to prevailing plaintiffs.

That award also violates standards generally accepted by the

legal profession as defining the factors relevant to deter

minations of reasonable counsel fees.

The Title VII attorney's fee provision, 42 U.S.C. §2000e

-5(x), does not by its terms set out any standards governing

the award of fees, other than that such an award be "reasonable".

In this circumstance, other professionally accepted enumerations

of the standards applicable to civil litigation generally

should be considered. Indeed, a number of courts in Title VII

and other public-interest actions have explicitly weighed and

applied those standards. E.g., Clark v, American Marine Corp.,

supra; Brotherhood of Railway Signalmen of America v. Southern

Railway Co., 380 F.2d 59,69 (4th Cir. 1967)(Railway Labor Act);

United States v. Gray, 317 F.Supp. 871 (D.R.I. 1970) (Title II).

These generally accepted and applicable standards are

set out in the ABA Code of Professional Responsibility, Ethical

Consideration 2-18 (1961), enforced according to Disciplinary

Rule 2-106 [hereinafter "DR-2-106"].

14/Application of these various factors to this case clearly

14 / We omit discussion of those factors which are clearly not

pertinent to this matter. 28

shows that the award below would be substantially less than a

reasonable fee, even for ordinary civil litigation of like

nature.

DB-2-106(B)(1). Time and Labor Required.

The time and labor required to win this case amounted to

659.5 hours (p. 6, supra). Defendant's Response questioned the

15/general reasonableness of the time spent (A. 79a-81a). At the

level of particularity, defendant only contested 66 of these

16/hours (pp. 7-9, supra). But defendant presented no evidence

that the same services should reasonably have been performed

in less time. On the contrary, plaintiff's expert witness,

Mr. Cashdan (who had substantial experience in preparing and

presenting many of the same issues (A. 123a-127a)) testified

without rebuttal or impeachment on cross-examination that the

time spent was in his view reasonable (A. 134a). Thus, there

H Defendant pointed particularly to the fact that its own

counsel had billed it for only 135 3/4 hours up to December 31,

1971 (A. 80a). That argument ignores several pertinent factors:

(1) Time-consuming final trial preparations for the January 31,

1972 trial and time spent at trial and on post-trial pleadings are

omitted from defendant's compilation (2) Preparation of a plain

tiff's case obviously requires more time than a defendant's case

- particularly where the client is not a corporation but an un

lettered individual and where (as in Title VII) the pertinent facts are for the most part within defendant's exclusive possession (A. 146a-147a). (3) Differences in amount of preparation may be

reflected in the results both on appeal and on remand.

16 / As to these hours, see n.12, supra. Even if they are wholly

excluded, 593.5 hours remain. The district court did not find

that these hours had not been spent.

29

is no evidence anywhere in the record to support the district

court's characterization of the number of hours that was

"reasonable". On these facts, this Court should not uphold the

district court award based on only 60 man-days of six to seven

17/hours each (A. 186a).

DR-2-106(B)(1). Novelty and Difficulty of Issues.

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express is a landmark case with

respect to two vitally important issues under Title VII. The

interlocutory appeal alone has been cited in at least 36 reported

decisions and is covered by a recent American Law Reports article.

See Shepherd's Federal Citations, Nos. 61-2 and 62-3; 8 ALR 2nd.

461. At the same time when most of this case was prepared the

the jurisprudence of Title VII was hardly existent, much less

developed. Johnson, however, established two important ground

rules for Title VII actions;(i) there is no right to a jury trial

and (ii) a plaintiff can mount an across-the-board attach on an

employer's employment practices without first proving he is en

titled to relief. The establishment of these principles was

most difficult due to meager legislative history, a tabula rasa

jurisprudence, and the inherent difficulty in assessing the

practical implications of and policy consideration in the questions

17/ The fact that much of the plaintiffs' time was spent liti

gating novel procedural issues designed to avoid adjudication

raised by defendant, and found by this Court to be meritless,

should obviously not work to defendant's advantage here.

30

°f right to jury trial and scope of the class action. Plaintiffs'

witnesses testified without contradiction as to the difficulty

and importance of the issues decided by the interlocutory appeal.

(A. 106a-107a, 131a-132a).

Like Griggs v. Duke Power Co.. 401 U.S. 424 (1971), which

took only a day and a half to try but has had a profound effect

on Title VII jurisprudence, the importance of Johnson far trans

cends the confines of the case itself and the time spent winning

it. The district court took no cognizance of this important

factor. Cf. Weeks v. Southern Bell Telephone Co., supra, 5 EPD

at p. 6545 (majority opinion) and pp. 6545-6546 (dissenting

opinion).

DR-2-106(B)(2). Preclusion from Other Employment

Mr. Moore, Mrs. McDonald and Mrs. Rindskopf, the private

Pra°Litioners whospent the bulk of the time on this case, were'

obviously precluded from other employment by the demands of this

lengthy and sometimes intense litigation. They are each civil

rights lawyers of wide repute, whose time is in demand.

DR-2-106 (B) (3) . Prevailing Local Fees.

There does not appear to be a schedule of rates and charges

specifically applicable to civil rights cases in Atlanta. Never

theless, the record shows that $50 per hour is considered reason

able and by no means a maximum charge for an experienced attorney

handling federal litigation (A.149a), with somewhat lesser rates

13'appropriate for inexperienced attorneys (Id.) Defendant's counsel

ill7 The most recent minimum fee schedules in the Atlanta area were withdrawn several months ago because they did not accurately reflect the inflation in hourly rates. Cf. Georgia Bar Reporter.

1972. Even the old schedule was $35 for experienced prac

titioners and $25 for less experienced lawyers. 6 Georgia State Bar Journal. No. 1, p. 13 (1969). -------------

apparently agreed (A. 160a).

DR-2-106(B)(4). Amount involved and Result Obtained

The case cannot be fairly characterized in terms of

the amount involved and the monetary results. Plaintiffs

asked for and ultimately received broad class relief from

racial discrimination (which injunctive relief will greatly

increase income opportunities for class members). The

victory for plaintiffs was a clear-cut and virtually total one

both in the nationally important interlocutory appeal and

after full trial. More importantly, plaintiffs vindicated

their rights in such a way as to blaze the trail for other

victims of racial discrimination. These factors were also

omitted from the district court’s determination of the fee

award.

DR-2-106 (B) (6). Nature and Length of Professional

Relationship

Unlike the defendant in this case which has a retainer

arrangement with its lawyers (A. 80a), plaintiffs simply

turned to attorneys of wide repute in civil rights matters

with no thought or need for an on-going professional relation

ship. Thus, the total compensation to plaintiffs' attorneys

for this matter must come from an award by the courts under

§ 706(k) and not from a retainer or a promise of future legal

business.

32

The testimony reflects the good reputation enjoyed by

plaintiffs' principal counsel, the firm of Moore, Alexander

& Rindskopf (A. 152a). Beyond that undisputed evidence,

however, this Court can and should take judicial notice of

the myriad of successful and important civil rights cases

in this circuit in which counsel have appeared. The conduct

and results of this case, and others in which plaintiffs'

counsel have appeared before this court, attest to the fact

that their abilities were equal to the rigorous demands of

this litigation.

As to the experience of counsel, all plaintiffs' attorneys

have spent most of their careers in civil rights litigation,

much of it under Title VII. indeed, the district court noted

these "accomplishments," but counter-balanced them against the

fact that at the time these services were rendered counsel

had relatively short experience (A. 186a). This finding of

the district court that plaintiffs' attorneys were not entitled

to full rates because of their inexperience must be evaluated

in light of the evident expertise of even plaintiffs' younger

attorneys in the rather specialized Title VII field. Experience

with the statute weighs heavily here. plaintiffs retained able

and experienced Title VII practitioners and the court below

erred in failing to consider that fact when determining which

end of the Atlanta fee scale to apply the efforts of these

lawyers.

DR-2-106 (B)(7). Experience, Reputation, and Ability

of Counsel

33

Plaintiffs have a contingent fee arrangement with their

attorneys (A. 62a, 65a) . -phis is typically the pattern in

civil rights cases in which impecunious victims of racial or

other discrimination are seeking to vindicate their rights.

Moreover, because of the nature of class action litigation

under Title VII, the contingency is one that may be realized

only after years (here almost five) of litigation and sub

stantial outlay of litigation costs. The court below failed

to consider this factor in any way. in light of the results

obtained and the broad import of this case, the amount requested

by plaintiffs— $30,145.50— is a bargain price for 659.5 hours

spent on a contingent basis by experienced and busy attorneys.

In sum, the award below did not even meet accepted

standards of the legal profession as to adequacy of compen

sation. In proper light of professionally accepted factors,

the award was unreasonably low— even apart from the special

public interest vindicated by this proceeding.

DR-2-106(B)(8). Contingency of the Fee

>

34

CONCLUSION

For the reasons set forth above, this Court should

reverse the judgment of the court below and should direct

that court to award plaintiffs attorney's fees in the

amount of $30,145.50, as plaintiffs requested below.

In the alternative, this Court should reverse and remand

for an award of more adequate attorney's fees based on

consideration of the appropriate policies and standards

as set forth above.

Respectfully submitted,

t , L -

j T ^ U - C C V - - C J -

HOWARD MOORE, JR.

ELIZABETH R. RINDSKOPF

75 Piedmont Ave., N.E. Atlanta, Georgia 30303

JACK GREENBERG

CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

MORRIS J. BALLER10 Columbus Circle

New York, N.Y. 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-

Appellants

JONATHAN HARKAVY Two Wall Street

New York, N.Y.

Of Counsel

3 5

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that I have served copies of

Appellants Brief in this matter by depositing the same

in the United States mail, air mail, postage prepaid,

addressed to counsel for appellees:

John W. Wilcox, Jr., Esq. Thomas M. Kuna, Esq.Suite 2620

Equitable Building

100 Peachtree St., N.W. Atlanta, Georgia 30303.

Done this 30th day of November, 1972.

Attorney

36