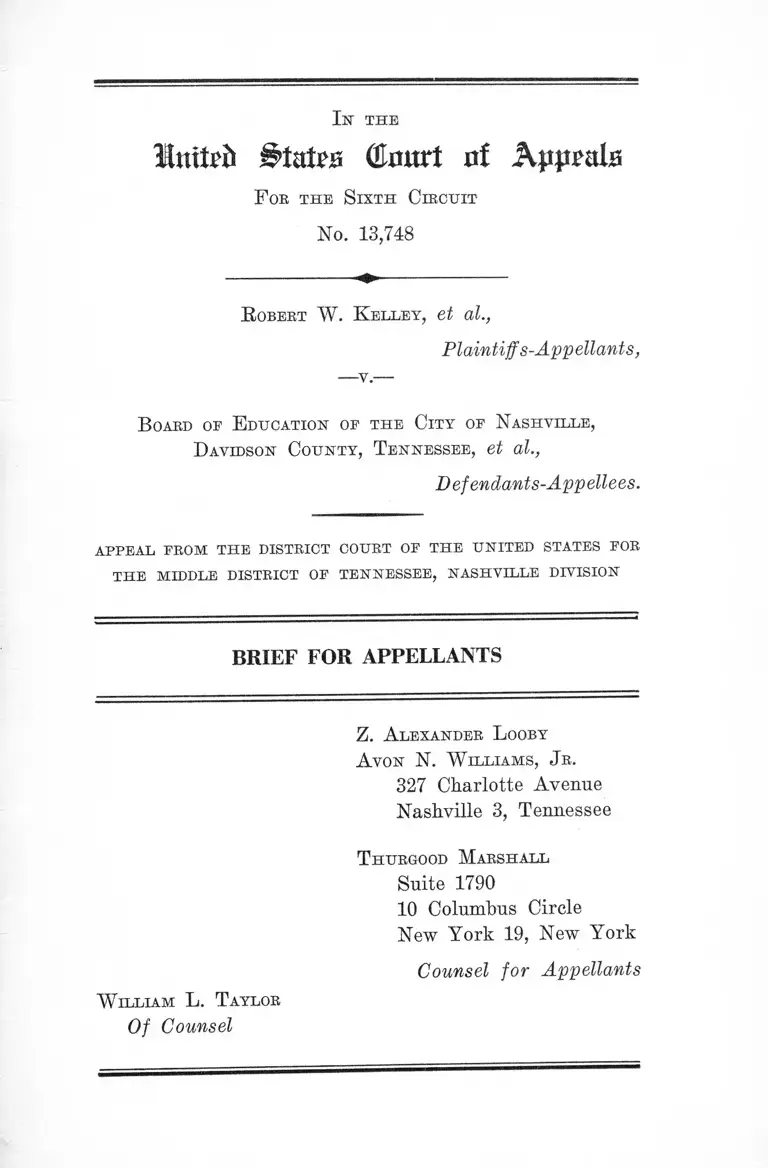

Kelley v. Metropolitan County Board of Education of Nashville and Davidson County, TN Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1958

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Kelley v. Metropolitan County Board of Education of Nashville and Davidson County, TN Brief for Appellants, 1958. dc5dbdce-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/52f98a3a-5d68-4f3e-86ed-87d7f31b567d/kelley-v-metropolitan-county-board-of-education-of-nashville-and-davidson-county-tn-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

I n THE

lutfrfc (ftmtrt of Appeals

F oe t h e S ix t h C ir c u it

No. 13,748

R o b er t W . K e l l e y , et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

B o ABD OF E D U C A T IO N OF T H E C lT Y OF N A S H V IL L E ,

D avidson C o u n t y , T e n n e s s e e , et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

A PPEA L FB O M T H E D ISTR IC T COU RT OF T H E U N IT E D STA TES FOB

T H E M ID D LE D ISTR IC T OF T E N N E S S E E , N A S H V IL L E D IV ISIO N

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Z. A l e x a n d e r L ooby

A von N . W il l ia m s , J b .

327 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville 3, Tennessee

T h u r g o o d M a r s h a l l

Suite 1790

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Counsel for Appellants

W il l ia m L. T aylor

Of Counsel

TABLE OF CONTENTS TO BRIEF

PAGE

Statement of Questions Involved ...... ............. ......... 1

Statement of Facts..................................................... 2

Argument ................. ....................-............................ 10

Belief ......................................................................- 21

T a b le of C a s e s :

Booker v. State of Tennessee Board of Education,

240 F. 2d 689 (6th Cir. 1957), cert, denied 353 U. S.

965 .......................................................................... 19

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483; 349 U. S.

294 ......... .............-....................................10,13,14,18, 20

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 139 F.

Supp. 468 (D. Kansas 1955)................................... 11

Clemons v. Board of Education of Hillsboro, 228 F.

2d 853 (6th Cir. 1956)...... ....................................... 19

Cooper v. Aaron,-----U. S. ——, 3 L. ed. 2d 5 (de

cided September 29, 1958) ............................ 10,13,16,19

Jackson v. Bawdon, 235 F. 2d 43 (5th Cir. 1956),

cert, denied 352 U. S. 925 ...................................... 10

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268 ................................... 13

McSwain v. County Board of Education, 138 F. Supp.

570 (E. D. Tenn. 1956) .......................................... 18

Mitchell v. Pollock, 1 Bace Bel. L. Bep. 1038 (W. D.

Ky. 1956); 2 Bace Bel. L. Bep. 305 (W. D. Ky.

1957) ....................................................................... 18

11

Pierce v. Board of Education of Cabell County,

(S. D. W. Va. 1956), unreported............-............... 18

Sliedd v. Board of Education of Logan County,

1 Race Eel. L. Rep. 521 (S. D. W. Ya. 1956) ...... 18

Shelley v. Ivraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 22............................ 13

Willis v. Walker, 136 F. Supp. 177 (W. D. Ky. 1955) 18

O t h e b A u t h o b it ie s :

Allport, The Nature of Prejudice (1954) ................. 15

Carmichael and James, The Louisville Story (1957) 14

Chein, Deutsch, Hyman and Jahoda, Ed., “Con

sistency and Inconsistency in Intergroup Rela

tions,” 5 Journal of Social Issues (1949) ............. 15

Clark, “Desegregation: An Appraisal of the Evi

dence,” 9 Journal of Social Issues (1953) ............. 14,15

Dean and Rosen, A Manual of Intergroup Relations

(1955) ......... ........................................................... 14,15

Kutner, Wilkens and Yarrow, “Verbal Attitudes and

Overt Behavior Involving Racial Prejudice,” 47

Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology

(1952) ........... 15

La Piere, “Attitudes v. Action,” 13 Social Forces

(1934) ....................... 15

Lee, “Attitudinal Multivalence in Culture and Per

sonality,” 60 American Journal of Sociology (1954-

55) ........... 15

IV Southern School News No. 11 (May 1958) .......... 14

Thompson, Ed., “Educational Desegregation, 1956,”

25 Journal of Negro Education (1956) ................. 14,15

Williams and Ryan, Schools in Transition (1954) .... 14,15

PAGE

TABLE OF CONTENTS TO APPENDIX

Docket Entries ................ la

Complaint................................................................... 4a

Answer ................ 14a

Supplemental Answer................................................ 32a

Transcript of Proceedings on November 13, 14, 1956 38a

P l a in t if f s ’ W it n e s s e s :

V. T. Thayer—

Direct ................................................... 39a

0. B. Hofstetter—

Direct ................................................... 44a

Memorandum Opinion of the Court.......................... 46a

Findings and Conclusions.................... .................... 57a

Judgment ................................................................... 65a

The Court’s Statement Delivered From the Bench .... 67a

O rder.......................................................................... 81a

Transcript of Testimony on January 28, 1958 .......... 82a

D e f e n d a n t s ’ W i t n e s s :

William H. Oliver'—-

Direct ................................................... 82a

Cross ..................................................... 84a

Opinion ...................................................................... 88a

O rder.......................................................................... 103a

Transcript of Proceedings on April 14, 1958 ............. 105a

I l l

PAGE

D e f e n d a n t s ’ W it n e s s e s :

William H. Oliver—

Direct ................................................... 107a

Cross ..................................................... 117a

Recalled by the Court.......................... 228a

Elmer Lee Pettit—

Direct ...... ........... -................................ 129a

Cross ..................................................... 134a

Redirect ................................................ 148a

Mary Brent—

Direct ................................................... 150a

Cross ..................................................... 156a

W. A. Bass—

Direct ................................................... 159a

Cross ..................................................... 163a

P l a in t if f s ’ W it n e s s e s :

Herman H. Long—

Direct ................................................... 171a

Cross ..................................................... 184a

Dr. Preston Valien—

Direct ................................................... 195a

Cross ..................................................... 201a

Mrs. Preston Valien—

Direct ................................................... 208a

Cross ........... 215a

Coyness L. Ennix—

Direct ................................................... 222a

Cross ..................................................... 224a

Redirect ............................................... 225a

Memorandum Opinion............................................... 236a

Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law................. 241a

Judgment ................................................................... 246a

iv

PAGE

I n t h e

HmtpJt Staten (Cmtrt of Appeals

F oe t h e S ix t h C ir c u it

No. 13,748

R obert W . K e l l e y , et al.,

Plaintiff s-Appellants,

--- Y.---

B oard o f E d u c a t io n o f t h e C it y o f N a s h v il l e ,

D avidson C o u n t y , T e n n e s s e e , e t a l.,

Defendants-Appellees.

A PPEA L FR O M T H E D ISTR IC T COU RT OF T H E U N IT E D STATES FOR

T H E M ID D LE D ISTR IC T OF T E N N E S S E E , N A S H V IL L E D IV ISIO N

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statem ent o f Q uestions Involved

I. May a Court in determining whether twelve years is

necessary to complete desegregation of a public school

system take into account community opposition as a

justification for the delay?

The Court below answered this question Yes.

Appellants contend that it should be answered

No.

II. Does a provision in a plan for public school desegre

gation sanctioning the transfer of students from

schools where they constitute a racial minority, or

2

from schools which previously served only members

of the other race, violate the equal protection clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution?

The Court below answered this question No.

Appellants contend that it should be answered

Yes.

III. Where a school board has failed to show that delay

is necessary for the solution of any particular prob

lem, and in fact has not even identified any specific

administrative obstacle to be overcome, may a court

approve a twelve-year plan for public school desegre

gation ?

The Court below answered this question Yes.

Appellants contend that it should be answered

No.

Statem ent o f Facts

Plaintiffs-appellants, Negro children who attend various

public elementary, junior high, and high schools in Nash

ville, Tennessee, and their parents, brought this action on

September 23, 1955 on behalf of themselves and those simi

larly situated, against the Board of Education of the

City of Nashville and its members, the Superintendent of

Schools for Nashville, and several public school principals,

seeking a declaratory judgment that the laws of Tennessee

requiring segregation of white and Negro children in public

educational facilities were unconstitutional, and an injunc

tion restraining defendants-appellees from refusing to

admit appellants to specified public schools, solely because

of their race (App. 4-12). Appellants’ complaint was

amended subsequently to add as parties plaintiff two

white children, and their parents, who had been denied

3

admission to schools operated on a segregated basis for

Negroes (App. 57).

Appellees answered, admitting that appellants had been

denied admission to the schools closest to their homes to

which they had applied, solely on the basis of race and that

laws requiring racial segregation were invalid (App. 14-

24, 38). Appellees alleged, however, that they intended

in good faith to implement the decision of the Supreme

Court in the School Segregation Cases, that a committee

had been appointed for the purpose of studying the prob

lems of implementation, that it had made two progress

reports, but that more time was needed to formulate a

plan (App. 17-24). Upon these representations, the Court

granted appellees’ motion for a continuance of the case

until the October 1956 term (App. 47).

When the case was called at the October 1956 term, the

Board of Education moved to postpone it until after the

meeting of the 1957 legislature of Tennessee, on the as

sumption that the legislature might pass laws relevant to

the issues of the case. This motion was denied (App. 69).

On November 13, 1956, appellees submitted to the Court

a plan embodying the following provisions: abolition of

“compulsory segregation” in Grade One of the elementary

schools beginning September, 1957; the establishment of

a zoning system for Grade One based on residence and

without reference to race; the establishment of a transfer

system allowing the transfer of white and Negro students

who would otherwise be required to attend schools pre

viously serving only members of the other race and allow

ing the transfer of any student from a school where the

majority of the students are of a different race; setting

December 31, 1957 as the date for a further recommenda

tion by the Board of Education’s Instruction Committee as

to the time and number of grades to be included in the nest

step to abolish segregation (App. 47-48).

4

After hearing on November 13, 1956, the court below

held that the plan presented by appellees was adequate,

amending it only to require that the Board of Education

submit by December 31, 1957 a report setting forth a com

plete plan to abolish segregation in the remaining grades

of the city school system, including a time schedule. The

Court retained jurisdiction but withheld the issuance of

an injunction pending the filing of the new plan (App. 52-

56).

On August 30, 1957, the Board of Education filed a

motion for leave to file a supplemental answer and counter

claim, alleging that Chapter 11, Public Acts of Tennessee

for 1957, authorized the establishment of separate schools

for white and Negro children whose parents elect that

such children attend schools with members of their own

race, that petitions had been received from parents urging

the establishment of such separate schools, and seeking a

declaration of its right to operate separate schools in light

of the prior judgment of the Court (App. 67-72). After

argument, during which the Board sought to sustain the

validity of Chapter 11, the Court ruled the statute uncon

stitutional and denied the Board’s motion for leave to file

a supplemental answer and counterclaim (App. 73-81).

On December 6, 1957, the Board filed with the Court a

document described as “a complete plan to abolish segre

gation in all grades of the City School System” which con

templated the establishment of a system substantially the

same as that authorized by Chapter 11, which the Court

had previously ruled unconstitutional. By the terms of

the plan, an annual census was to be conducted to deter

mine which parents desired their children to attend schools

with members of their own race exclusively and which

parents desired that their children attend schools with

members of another race. On the basis of this poll three

5

types of schools were to be operated: schools for Negro

students whose parents preferred that their children at

tend segregated schools, schools for white students whose

parents preferred that their children attend segregated

schools, and schools for students whose parents preferred

that they attend integrated schools (App. 90, 97-98).

On January 20, 1958, the Board filed a motion to dismiss

this case on the ground that the Tennessee Pupil Assign

ment Act, Chapter 13, Public Acts of 1957, approved a

year earlier, provided an adequate administrative remedy

which must be exhausted before the rights of appellants

to transfer to different schools could be judicially deter

mined (App. 91). After hearing on January 28, 1958, the

court: (1) denied the motion to dismiss, finding that the

Board of Education was committed to a policy of continu

ance of compulsory segregation and that the remedy pro

vided by the Pupil Assignment Act was not adequate, and

(2) disapproved the Board’s plan of December 6, 1957,

holding that, like Chapter 11, it failed to meet the test of

constitutionality because it would give the sanction of law

to a continuation of compulsory segregation in public edu

cation (App. 88-101). The Court, however, again with

held the issuance of an injunction, and allowed the Board

until April 7, 1958 to file another plan to eliminate racial

discrimination in its school system (App. 103-104).

On April 7, 1958, the Board filed with the Court a plan

contemplating the abolition of “compulsory segregation”

in Glrade Two in September, 1958 and in one additional

grade a year thereafter until completion, and retaining the

zoning and transfer provisions contained in the plan first

approved by the Court (App. 236-237).

After hearing, the Court on July 17, 1958 entered an

order approving the Board’s plan in its entirety, denying

appellants’ prayer for injunctive relief and retaining juris

6

diction during the period of transition (App. 246). The

Court found that the witnesses for appellees, “based upon

their years of experience in education and upon their in

timate knowledge of conditions in Nashville, sincerely be

lieve” that a sudden transition would “engender admin

istrative problems” of great magnitude; that the appellees

were actuated by a belief that the twelve-year plan was

necessary to minimize the effect of community opposition

to integration; that the appellants’ witnesses had no direct

connection with the Nashville public schools (except for

one witness who was a member of the School Board) and

that they disagreed among themselves as to the best plan

for desegregation; that it is not the province of the Court

to operate the public schools and that the judgment of the

Board had been sustained by a clear preponderance of

the evidence (App. 236-240). Notice of appeal to this

Court was filed by appellants on August 15,1958.

Nashville’s public school system consists of some forty-

six schools with a total enrollment of 27,595, of whom

10,322 are Negro students (App. 58). The enrollment in

the first grade of the school system is approximately 3400,

of whom 1400 are Negro students (App. 58-59). Because

of residential segregation, only 115 of the 1400 Negro

students in the first grade were eligible to attend schools

previously attended only by white students, under a zoning

system based upon residence (App. 86-87). Only 55 of the

2000 white students in the first grade were eligible to

attend schools previously attended only by Negro students

(App. 82). All 55 of the white students sought and were

granted transfers and 105 of the 115 Negro students were

granted transfers (App. 83). Several parents of the 105

sought re-transfers to enable their children to attend in

tegrated schools, but these applications were denied by

the Superintendent because he felt that the children did

not want to be re-transferred and that the parents had

7

been influenced by others and did not have good reasons

for seeking re-transfer (App. 84-86). Thus, because of the

pattern of residential segregation, only a small percentage

of the school population will be affected by the plan for

desegregation (App. 86-87).

At the hearing on April 14, 1958, all of appellees’ wit

nesses—W. H. Oliver, Superintendent of Schools for Nash

ville, Elmer Lee Petit, acting chairman of the School

Board, Mary Brent, principal of a Nashville elementary

school, and W. A. Bass, former Superintendent of Schools

—testified that a major reason for their support of the

twelve-year plan was their belief that a majority of the

citizens of Nashville were strongly opposed to desegrega

tion and that the twelve-year plan was the one most in

accord with the wishes of the majority and would engender

the least community opposition (App. 112-116, 132-133,

155-156, 165-166). Appellees’witnesses expressed the belief

that only a gradual plan of the twelve-year variety would

allow smooth adjustments to be made in the educational

process.

The school principal testified that there had been some

disturbances outside her school at the beginning of the

1957 term, that there had been unusual absenteeism during

the first month of school, that she had been the victim of

abusive phone calls, that many parents personally regis

tered to her their protests against desegregation, that some

parents had refused to join the PTA because Grade One

had been desegregated and that there had been a couple

of incidents involving discrimination by older children

against Negro first-graders (App. 152-153). In spite of

this, she testified that little tension was felt within the

school itself and that the education of both white and

Negro first-graders had progressed satisfactorily (App.

153, 158) but felt that this might not be the case with older

8

children who were conscious of race differences (App. 158-

159).

The Superintendent of Schools added that the twelve-

year plan would make possible a more homogeneous group

ing of students, in that if large numbers of students were

involved in a speedier plan for desegregation, students of

different backgrounds and levels of achievement might

be placed in the same classes (App. 115). He conceded,

however, that homogeneity was not “exactly” a racial

matter and that the problem of achieving homogeneous

groupings had existed for a long time and would con

tinue to exist irrespective of desegregation (App. 118-119,

124-125).

The former Superintendent of Schools indicated that he

favored the twelve-year plan because, based on his past

experience, he anticipated that the attitudes of teachers

might cause some difficulty (App. 161-162).

These were the only matters mentioned by appellees’

witnesses. None of appellees’ witnesses identified any

specific administrative problem to be solved; nor was any

attempt made to demonstrate that the delay entailed in

the twelve-year program was necessary for the solution

of any particular problem.

—Appellants’ witnesses were a psychologist and two sociol

ogists, all of whom held or had held college teaching posi

tions and had done research, writing and consultative work

in the field of race relations and desegregation (App. 171a. ~-

175?t 19 -̂196 ̂ 208̂ 20̂ .). Appellants’ fourth witness was

the lone Negro member of the Nashville Board of Educa

tion (App. 222 .̂ "

A

These witnesses testified that actual experience with de

segregation in several localities demonstrated that delay

increases rather than decreases community antagonism

9

( 4 p - 177-178, 197-200, 210-211). They stated that delay

creates doubts and resistance in the public mind (App. 177:<

178); and further confusion is engendered by singling out

particular grades for desegregation and breaking up fam

ily units (App. 198-199). Conversely, in communities

where desegregation was accomplished rapidly, tensions

were minimized (Aipp. 178,' 210-211). Expressed attitudes

against desegregation did not manifest themselves in ac-

f l ®*ttion (Ap-p. 211) and the apprehensions of teachers that de

segregated classes could not be taught successfully proved

unwarranted (App. 174).

Two of appellants--- witnesses contended that desegrega-

tion should take place immediately (App. 210, 243), while

two others suggested that it could be accomplished by

functional units in a two or three-stage plan (App. 206,'

,-223). All of appellant-& ̂witnesses, however, opposed the

twelve year program (Afpp-. 177-178, 197-200, 210, 222j and

none stated a belief that desegregation could not prac

ticably be put into effect immediately.

Appellants contend that the Court below erred in approv

ing a twelve-year plan on the ground that it was necessary

to minimize community hostility; in holding that a transfer

provision in that plan based upon racial criteria does not

violate the Fourteenth Amendment; in approving delay

where appellees had not sustained their burden of showing

that it was necessary to overcome legitimate administrative

problems, and in fact had not even identified any specific

administrative obstacle; and in refusing to issue an in

junction requiring immediate desegregation of the public

schools of Nashville.

1 0

A R G U M E N T

I. May a Court in determ ining w hether twelve years is

necessary to com plete desegregation o f a public

school system take into account com m unity opposi

tion as a justification for the delay?

The Court below answered this question Yes.

A ppellants contend that it should be answered No.

In Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294, the

Supreme Court in formulating a decree to effectuate its

prior decision that racial segregation in the public schools

is a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment, said at page

300:

Courts of equity may properly take into account the

public interest in the elimination of such obstacles in

a systematic and effective manner. But it should go

without saying that the vitality of these constitutional

principles cannot be allowed to yield simply because

of disagreement with them.

This pronouncement was interpreted almost uniformly

as prohibiting the consideration of community opposition

to desegregation as a justification for delay. See, e.g.,

Jackson v. Rawdon, 235 F. 2d 93 (5th Cir. 1956), cert,

denied 352 U. S. 925. Any lingering doubts on this score

were put to rest in Cooper v. Aaron, —— U. S .----- , 3 L. ed.

2d 5, 10 (decided September 29, 1958); where the Supreme

Court, in rejecting an appeal by the Little Rock School

Board which urged suspension of its plan for desegregation

because violence had occurred, specifically ruled that hos

tility to racial desegregation is not a relevant factor in

determining whether justification exists for not requiring

immediate nonsegregated education.

1 1

Yet the appellees here frankly conceded that community

hostility to desegregation was a major factor in devising

the time schedule (App. 112-116, 132-133, 155-156, 165-166),

and the Court below took specific cognizance of this fact

as a basis for approving the plan (App. 237-238). This,

appellant submits, is reversible error.

II. D oes a provision in a plan for public school desegre

gation sanctioning the transfer o f students from

schools where they constitute a racial m inority, or

from schools w hich previously served only m em bers

o f the other race, violate the equal protection clause

o f the Fourteenth A m endm ent to the U nited States

Constitution?

T he Court below answered this question No.

Appellants contend that it should be answered

Yes.

The Court below here has approved a provision sanc

tioning the use by public officials of racial criteria in the

assignment of children to schools (App. 53-55, 236).

In Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 139 F. Supp.

468 (D. Kansas 1955), the Board of Education of Topeka

submitted a plan with a provision similar to the one here

in question, which permitted children entering school to

elect whether they would attend schools near their homes

or in another district. The District Court held that this

provision did not comply with the Supreme Court’s man

date. The Court, however, did not condemn the whole

plan, because the transfer provision was to be of only a

year’s duration.

The transfer provision in the Brown case was held

wanting even though, unlike the provision in the instant

case, it made no specific reference to race.

1 2

The Court below in this case itself condemned a plan

which contemplated the establishment of a system of

segregated and integrated schools based upon parents’

preferences. In this connection, the Court said (App. 99-

100) :

Another objectionable feature to the plan is that

it does not offer in any realistic sense an alternative

or choice to the members of the minority race. To

hold out to them the right to attend schools with

members of the white race if the members of that race

consent is plainly such a dilution of the right itself

as to rob it of meaning or substance. The right of

negroes to attend the public schools without discrim

ination upon the ground of race cannot be made to

depend upon the consent of the members of the ma

jority race.

This reasoning also constitutes a fatal objection to the

transfer provision here in question. The sanction of trans

fers from desegregated schools on grounds of the racial

composition of the school or its previous racial designa

tion clearly impinges on the right to a nonsegregated edu

cation. In authorizing one group of children to transfer

from desegregated schools in their neighborhoods because

of their racial attitudes (or those of their parents), the

right of another group to attend these desegregated schools

is clearly made to depend on the consent of the first. The

operation of this transfer provision already has resulted

in continued segregation in schools which otherwise would

have been desegregated (App. 82-83).

Appellees cannot under the guise of extending “free

dom of choice” to one group so restrict it for another.

This is especially true where the provision authorizes the

consideration of race as a factor in the assignment of

children to public schools. The “optional” character of

13

such provisions does not save them from condemnation.

Cf. Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483; where

the Supreme Court struck down a Kansas statute which

permitted but did not require the maintenance of segre

gated public schools, along with other statutes which were

mandatory. Nor is it any answer to say that Negro

children may also avail themselves of the transfer pro

vision, for “ [e]qual protection of the laws is not achieved

through indiscriminate imposition of inequalities.” Shelley

v. Kramer, 334 U. S. 1, 22.

The prohibitions of the Constitution extend to sophisti

cated as well as to simple-minded modes of discrimination.

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268, 275; and the “rights of

children not to be discriminated against in school admission

on grounds of race or color” cannot be nullified “through

evasive schemes for segregation whether attempted ‘in

geniously or ingenuously.’ ” Cooper v. Aaron, ----- - U. S.

----- , 3 L. ed. 2d 5, 16.

III. W here a school board has fa iled to show that delay

is necessary for the solu tion o f any particular

problem , and in fact has not even identified any

specific adm inistrative obstacle to be overcom e,

m ay a Court approve a twelve-year plan for public

school desegregation?

The Court below answered this question Yes.

Appellants contend that it should be answered

No.

A. The Twelve-Year Plan.

Appellants submit that the racial transfer provision

cannot be allowed to stand and that the sanctioning of

delay because of community hostility by the Court below,

14

was in itself error sufficient to require reversal.1 * * IV But the

error in approving appellees’ twelve-year plan was even

more far-reaching.

In Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294, the

Supreme Court recognized that good faith compliance

1 Even if consideration of community hostility were permissible, there

is no warrant for the assumption made by the court below that a twelve-year

plan was a good method for overcoming such antagonism. Actual experience

in desegregation indicates that the contrary is true.

Desegregation has been accomplished successfully over a relatively short

span of time in Louisville, Kansas City, St. Louis, Washington, D. C., Wilming

ton and Baltimore. On the other hand, court approval of a drawn out plan

in Little Bock apparently did nothing to foster community acceptance. School

officials in some of the former communities have clearly stated the compelling-

reasons that led them to decide against a protracted plan and their satisfac-

tioiTwith the results of the plans adopted. Carmichael and James, The Louis

ville Story, especially 83 (1957) :

“Experience elsewhere indicated that a partial or geographic change par

ticularly might lead to mushrooming opposition. Desegregating a grade

at a time or several grades at a time obviously would increase social con

fusion by having some children in a single family attend mixed schools

while others remained in segregated schools. Administrative difficulties,

too, obviously would be compounded by any partial program. And we

decided that universality of participation by the entire school staff from

the very beginning would greatly increase the chances of success.”

IV Southern School News No. 11, p. 3 (May 1958). [Washington, D. C. School

Board President Tobriner:

“I thank goodness that we were smart enough or shall I say lucky

enough to avoid the gradualism in integration which so many people

urged upon us.”]

The testimony of appellants’ witnesses (App. 177-178, 197-200, 210-211)

and leading race relations authorities further document these conclusions. Ex

amination of actual instances of desegregation reveals that segmentalized de

segregation, including progressive desegregation by grades, does not allay

anxieties or doubts, or assure greater community acceptance of desegregation.

Clark, “Desegregation: An Appraisal of the Evidence,” 9 Journal of Social

Issues 1-68, especially 45-46 (1953) ; Dean and Rosen, A Manual of Inter

group Relations 57-105, especially 70 (1955) ; Thompson, Ed., “Educational

Desegregation, 1956,” 25 Journal of Negro Education (1956) ; Williams and

Byan, Schools in Transition 241-244 (1954).

Bather, such methods appear to mobilize the resistance of those white

persons immediately affected, since they feel themselves arbitrarily selected as

an “experimental” group. The remainder of the community then observes con

flict rather than peaceful adjustment; anxieties are increased and resistance

15

might “call for elimination of a variety of obstacles in

making the transition to school systems operated in ac

cordance with the constitutional principles set forth in

our May 17,1954 decision.” District courts were authorized

to consider “problems related to administration, arising

from the physical condition of the school plant, the school

transportation system, personnel, revision of school dis

tricts and attendance areas into compact units to achieve

a system of determining admission to the public schools

on a nonracial basis, and revision of local laws and regula

tions which may be necessary in solving the foregoing

problems.” 349 U. S. at 300, 301.

But the District Courts were directed to require “a

prompt and reasonable start toward full compliance” and

to take such action as was necessary to bring about the

end of racial segregation in the public schools “with all

deliberate speed.” Ibid. Time might be allowable, the

Court held, but “ [t]he burden rests upon the defendants

to establish that such time is necessary in the public in

terest and is consistent with good faith compliance at the

earliest practicable date.” (Emphasis added.) Ibid.

stiffens. This reaction may become self-perpetuating. Moreover, an extended

time schedule may be interpreted by the community as indicative of hesitancy

about ending segregation or of an intention to evade compliance. Here again,

delay may foster resistance rather than acceptance. See authorities cited above.

Adoption of a segmentalized plan often is predicated upon the erroneous

assumption that changes in attitude must precede desegregation. Experience

indicates that public acceptance often follows, rather than precedes, the enforce

ment of non-segregation and that the resistance anticipated is often much

greater than that actually encountered when desegregation occurs. Allport,

The Nature of Prejudice (1954) ; Chein, Deutseh, Hyman and Jahoda, Ed.,

“Consistency and Inconsistency in Intergroup Relations,” 5 Journal of Social

Issues 1-63 (1949); Kutner, Wilkens and Yarrow, “Verbal Attitudes and Overt

Behavior Involving Racial Prejudice,” 47 Journal of Abnormal and Social

Psychology 649-652 (1952) ; La Piere, “Attitudes v. Action,” 13 Social Forces

230-237 (1934) ; Lee, “Attitudinal Multivalenee in Culture and Personality,”

60 American Journal of Sociology 294-299 (1954-55); and see other authorities

cited above.

Thus actual experience establishes that delay, far from facilitating a change

in community attitudes, often serves to impede it.

16

These principles were reaffirmed in Cooper v. Aaron,

-----U. S .------ , 3 L. ed. 2d 5, 10-11. There the Court said

at 10-11:

Of course, in many locations, obedience to the duty of

desegregation would require the immediate general

admission of Negro children, otherwise qualified as

students for their appropriate classes, at particular

schools. On the other hand, a District Court, after

analysis of the relevant factors (which, of course, ex

cludes hostility to racial desegregation), might con

clude that justification existed for not requiring the

present nonsegregated admission of all qualified Negro

children. In such circumstances, however, the courts

should scrutinize the program of the school authori

ties to make sure that they had developed arrange

ments pointed toward the earliest practicable comple

tion of desegregation, and had taken appropriate steps

to put their program into effective operation. It was

made plain that delay in any guise in order to deny

the constitutional rights of Negro children could not

be countenanced, and that only a prompt start, dili

gently and earnestly pursued, to eliminate racial seg

regation from the public schools could constitute good

faith compliance. (Emphasis added.)

In the instant case, appellees made no attempt to show

that twelve years was the “earliest practicable date” for

completion of desegregation, nor did the Court below find

that such a showing had been made. Note was made of the

sincerity of the appellees despite the fact that on Febru

ary 18, 1958, the Court had found that the Board was com

mitted to a policy of continued segregation (App. 94).

This finding was based upon the fact that appellees had

sought delay at every stage of the litigation and had put

forward schemes designed solely to evade compliance with

17

desegregation.2 Even if these circumstances are not deemed

to reflect upon the good faith of the appellees, good faith

alone is not sufficient to sustain their plan.

Appellees have not suggested the existence of any ad

ministrative obstacle within the limited category author

ized by the Supreme Court for consideration. The Super

intendent testified that a homogeneous grouping of students

was a desirable educational goal and that if large numbers

of students were involved in a speedier plan for desegre

gation, students of different backgrounds and levels of

achievement might be placed in the same classes (App. 115).

But he admitted that homogeneity was not precisely a

racial matter and that it was a continuing problem (App.

118-119, 124-125). In fact, by his own testimony, large

numbers of students would not be involved in immediate

desegregation (App. 87). And in any case, no suggestion

was made that twelve years would permit the taking of any

specific step to solve the problem.3 The former Superin

2 When this suit was first brought in 1955, the Board sought and obtained

a continuance on the ground that it needed further time for study (App. 47).

When the ease was called at the October 1956 term, the Board moved unsuccess

fully to postpone it until after the meeting of the 1957 Tennessee legislature

(App. 69). The Board then submitted a plan which provided only for desegre

gation of Grade One, did not provide any date certain for the submission of a

complete plan to abolish segregation, and embodied the racial transfer system

previously discussed (App. 47-48, 53). Next, the Board sought a declaratory

judgment to sustain the validity of a statute which authorized the maintenance

of segregated schools in accordance with the wishes of parents (App. 73).

When this plea was rejected the Board resubmitted it in substantially the same

form as a “complete plan to abolish segregation” (App. 90, 97-98). Then, the

Board sought to dismiss the action entirely, because of an alleged failure by

appellants to exhaust administrative remedies (App. 91). These pleas having

failed, the Board, under mandate to produce a plan, submitted the twelve-year

program now in controversy.

3 I t was not contended that the achievement levels of Negro students were

uniformly below those of white students. Such a statement would have no

basis in fact (App. 189-190). I f made, it would constitute an additional in

dictment of segregated schools and would hardly suggest that a solution was

to be found in perpetuating segregation and depriving all children now in the

schools of their rights to a nonsegregated education.

18

tendent of Schools indicated that it was his belief, based

on experience, that reconciling the attitudes of some teach

ers to desegregation might prove difficult. No evidence

was offered to demonstrate that delay would solve this

putative problem and no specific measures were proposed

to remedy it.

None of these matters were within the “problems relat

ing to administration” listed by the Supreme Court as

affording possible grounds for not requiring immediate

desegregation. Brown v. Board of Education, supra, at

300, 301. No attempt was made by appellees to connect

these matters to their twelve-year plan or to put forward a

specific program for utilizing time to resolve them. The

twelve year program was predicated solely upon commu

nity hostility. If this is removed as a consideration, there

is nothing in the record which indicates that desegregation

“at the earliest practicable date” cannot occur immediately.

Lower federal courts, while conceding the good faith of

the school boards involved, have rejected twelve year plans

identical to the one here offered, Mitchell v. Pollock, 1 Race

Eel. L. Rep. 1038 (W. D. Ky. 1956); Pierce v. Board of

Education of Cabell County (S. D. W. Ya. 1956), unre

ported ; and have ordered desegregation of school systems

either immediately or within one year. Willis v. Walker,

136 F. Supp. 177 (W. D. Ky. 1955); McSwain v. County

Board of Education, 138 F. Supp. 570 (E. D. Tenn. 1956);

Shedd v. Board of Education of Logan County, 1 Race Rel.

L. Rep. 521 (S. D. W. Va. 1956); Mitchell v. Pollock, 2 Race

Rel. L. Rep. 305 (W. D. Ky. 1957); Pierce v. Board of Edu

cation of Cabell County, supra. In the Pollock case, the

Court, noting that the school board had acted in good faith,

that the twelve year plan was presented after thorough

consideration and that some advances toward desegrega

tion had been made, still rejected the plan, subsequently

19

refused to accept a four-year plan and, finding that the

only justification for delay was community opposition,

ordered that all schools be desegregated at the next se

mester.

This Court has refused to accept generalized and un

substantiated pleas for delay even when made in good

faith, has ruled that factors like overcrowding in white

schools provide no excuse for the refusal to admit quali

fied Negro applicants, and has held that a trial court has

no discretion to continue the deprivation of basic human

rights by denying an injunction. Clemons v. Board of

Education of Hillsboro, 228 F. 2d 853 (6th Cir. 1956);

Booker v. State of Tennessee Board of Education, 240 F.

2d 689 (6th Cir. 1957), cert, denied 353 U. S. 965.

B. The C onstitu tional R ights o f A ppellan ts.

The Court below contended that approval of the twelve-

year plan did not involve a denial, but merely a postpone

ment of the constitutional rights of appellants and those

similarly situated. When a similar assertion was made on

September 11, 1958 in oral argument by counsel for the

school board in Cooper v. Aaron, this colloquy ensued:

The Chief Justice: But if we stop that program,

we are denying this same right to approximately 40

percent of the children of your community, aren’t we!

Mr. Butler: We take the position that you are not

denying the right. You are delaying the fulfillment of

a constitutional right which you have said they have,

but not the denial of the right as a class action, which

this is.

The Chief Justice: Well, this decision, the Brown

decision, was in 1954. This is 1958. Two years and a

half will bring it up almost to 1961. Now if all those

children are denied the right to go to the elementary

2 0

schools, aren’t they being denied permanently and

finally a right to get equal protection under the laws

during their primary grade years! (Tr. 49)

Nothing more graphically illustrates the injustice of

this plan and its failure to meet minimum constitutional

standards than the fact that under it, all of the appellants

and every Negro child who was in a Nashville public school

prior to September, 1957, will forever be denied the right

to an unsegregated education.4 Perhaps it is conceivable

that in some case a strong enough showing of administra

tive problems could be made to justify denying to a whole

generation of school children their constitutional rights

to attend unsegregated public schools. No such showing

has been made here.

i Appellees sought to minimize the injury caused to appellants by delay

by demonstrating the physical equality of white and Negro schools (App. 19).

Of course, this contention, even if true, does not mitigate the harm caused by

segregation. Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483. But even this claim

was refuted by the evidence (App. 197-198, 228-229).

2 1

RELIEF

For the reasons hereinabove indicated, it is respect

fu lly subm itted that the judgm ent o f the Court below

should be reversed and rem anded w ith directions to

issue an in ju nction restraining appellees from refusing

to adm it appellants and all those sim ilarly situated to

unsegregated public schools in Septem ber, 1 9 5 9 .

Respectfully submitted,

Z. A l e x a n d e r L ooby

A v on N. W il l ia m s , J r .

327 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville 3, Tennessee

T h u b g o o d M a r s h a l l

Suite 1790

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Counsel for Appellants

W il l ia m L . T aylor

Of Counsel