Powell v. Wiman Opinion

Public Court Documents

February 24, 1961

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Powell v. Wiman Opinion, 1961. f3260975-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/52fcc4eb-36a7-49d0-bc81-8438a58c5fa2/powell-v-wiman-opinion. Accessed March 13, 2026.

Copied!

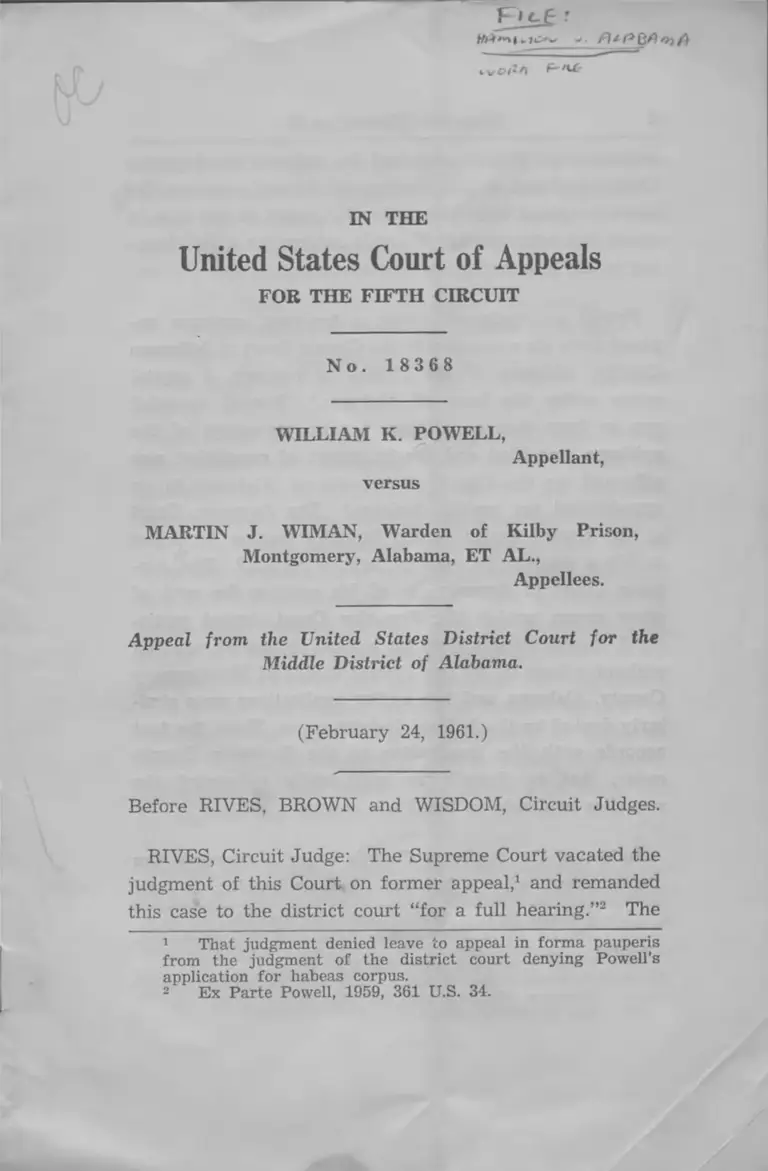

IN THE

F r c f f

United States Court of Appeals

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

N o . 1 8 3 6 8

WILLIAM K. POWELL,

Appellant,

versus

MARTIN J. WIMAN, Warden of Kilby Prison,

Montgomery, Alabama, ET AL.,

Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Middle District o f Alabama.

(February 24, 1961.)

Before RIVES, BROWN and WISDOM, Circuit Judges.

RIVES, Circuit Judge: The Supreme Court vacated the

judgment of this Court on former appeal,1 and remanded

this case to the district court “for a full hearing.”2 The

1 That judgment denied leave to appeal in forma pauperis

from the judgment of the district court denying Powell’s

application for habeas corpus.

2 E x Parte Powell, 1959, 361 U.S. 34.

2 Powell v. Wiman, et al.

district court at first construed the order of the Supreme

Court to direct a full hearing on Powell’s motion for

leave to appeal from the earlier judgment of the district

court, but later granted Powell’s motion for a full hear

ing on his application for habeas corpus.

Powell is imprisoned under a ten-year sentence im

posed upon his conviction in the Circuit Court of Jefferson

County, Alabama, of the offense of robbery, a capital

crime under the laws of Alabama.3 Powell appealed

pro se from that conviction, but no transcript of the

evidence was filed and the judgment of conviction was

affirmed by the Court of Appeals of Alabama in an

unpublished per curiam decision.4 The Supreme Court

of the United States denied Powell’s motion for leave

to file a petition for writ of habeas corpus.5 * The Ala

bama Court of Appeals denied his petition for writ of

error coram nobis.® The Superior Court denied certio

rari.7 Powell’s application for habeas corpus was denied

without a hearing by the Circuit Court of Montgomery

County, Alabama, and two earlier applications were simi

larly denied by the federal district court. Thus, the fact

accords with the implication of the Supreme Court’s

order, that is, Powell has sufficiently exhausted the

remedies available in the State courts.8

Following the Supreme Court’s order of remand, the

district court, after a full and adequate hearing, entered

3 Alabama Code of 1940, Title 14, Section 415.

4 See E x Parte Powell, Ala. App. 1958, 102 So.2d 923,

925.

B Powell v. Burford, 1957, 355 U.S. 888.

« E x Parte Powell, Ala.App. 1958, 102 So. 2d 923.

7 Powell v. Alabama, 1958, 358 U.S. 850.

3 See 28 U.S.C.A. §2254.

Powell v. Wiman, et al. 3

a memorandum opinion finding adversely to Powell on

each of his many contentions, and denied his petition

for habeas corpus. From that judgment the present

appeal is prosecuted. Of the many contentions presented

on this appeal, it is necessary to consider only two:

I. Powell was not represented by counsel on

his. arraignment for the capital offense of robbery.

II. The State suppressed vital evidence upon

Powell’s trial.

As to the first contention, the district court found

that Powell was arraigned upon the indictment and

entered a plea of not guilty; that he was not then

represented by counsel; that on the same day and during

the same court appearance and shortly after Powell

entered a formal plea of not guilty, the court appointed

two attorneys to represent Powell; that, thereafter, the

prosecuting attorney agreed that the arraignment be

set aside if Powell’s court-appointed attorneys so re

quested ;̂ that Powell and his attorneys decided against

such action, and elected instead to conduct his trial on

the plea of not guilty without pleading “not guilty by

reason of insanity.” After carefully reading and study

ing the record and exhibits, we agree with those fact

findings of the district court.

While the present appeal has been pending, the Su

preme Court of Alabama has ruled upon another capital

case presenting much the same question of law that is

posed by those facts.9 In that case the defendant was

not represented by counsel at his arraignment and for

9 E x Parte Hamilton, Ala.. 1960, 122 So. 2d 602.

4 Powell v. Wiman, et al.

three days thereafter. Upon trial, he was convicted

and sentenced to death. The Supreme Court of Alabama,

upon a finding that the defendant was not prejudiced

by the late appointment of counsel, denied him leave

to file in the trial court an application for writ of error

coram nobis. On the 9th day of January 1961, the

Supreme Court of the United States granted „ certiorari

to review that decision. Hamilton v. Alabama, 1961,

No. 640.........U.S........... ,2 9 L.W.3203. We do not await the

decision of the Supreme Court in that case, and refrain

from expressing any view on the question of law, be-

cause the present case can and should be decided upon

Powell’s other contention to the effect that the State

suppressed vital evidence upon his trial. Consideration

of that issue requires a detailed examination of the facts,

as disclosed both by the transcript of the evidence upon

Powell’s trial for robbery, now made available to an

appellate court for the first time, and by the full hearing

on Powell’s petition for habeas corpus conducted by the

district court.

On Sunday night, September 25, 1955, Mr. L. O. Brown

closed his ice cream store in Birmingham, Alabama, at

a late hour. He and his wife, with about $25.00 in

currency from the day’s receipts, arrived home after

11:00 P.M. As their automobile stopped at their garage

and Mrs. Brown started to get out, a man with a pistol

approached the driver’s side and ordered Brown to have

his wife get back in the car; Mrs. Brown, of course,

complied. Brown later identified that man as one James

Hatt, and it is now established without dispute that the

robber was James Hatt. Brown offered Hatt the money

Powell v. Wiman, et al. 5

which was in a cloth sack on the seat beside him, but

Hatt at that time declined and ordered him instead to

drive out of town. Hatt got in the back seat and held

the pistol on Brown, directing him where to drive, first

16 or 17 miles down the Highway toward Montgomery,

then turning off on a road that led from the Montgomery

Highway to the Atlanta Highway, then turning off down

a little-traveled dirt road for about a hundred yards,

where Hatt ordered Brown to stop and turn off his lights.

Hatt took the sack of money and searched the automobile

for more, but without success. He then took the auto

mobile keys, made Brown let the air out of the tires,

ordered him to get back in the car and shut the door,

and, according to Brown’s testimony on Powell’s criminal

trial: “He said I am going to watch and if you open

that door the light will come on, and made some state

ment as to how he could shoot, he had been shooting

squirrels since he was a boy. And he said after a car

stops in the highway and I have gotten in it and gone

you can do what you want to.”

The Browns stayed in their automobile for a “good

while,” but neither saw nor heard a car stop on the near

by highway. Finally, they got out, walked to the high

way, found a telephone, and reported the robbery. The

Browns did not see Powell at the scene of the crime.

The next scene is at a tourist home in Leeds, Alabama,

on the night of September 30, 1955, five days after the

robbery. There B. M. Dinkin, a Deputy Sheriff of

Jefferson County, and John Pledger, Chief of Police of

Leeds, arrested Hatt. In the room with Hatt was the

appellant, William K. Powell. Under the mattress of

the bed the officers found a pistol with a shoulder

holster, some cartridges, a “slapjack,” a pair of rubber

gloves, and a mask. Upon Powell’s criminal trial, Hatt

admitted that these articles belonged to him.

Powell and Hatt were taken to police headquarters in

Leeds, where they were questioned jointly by Officers

Pledger and Dinkin and by the Mayor of Leeds. Hatt

admitted having committed the armed robbery, but

Powell has made no confession either then or at any

subsequent time. Upon their arrival in Birmingham,

Hatt was taken to the office of the prosecuting attorney,

where he gave a detailed written statement. In due

course, Hatt and Powell were separately indicted for

the offense of the armed robbery of L. O. Brown.

Powell was tried on January 25 and 26, 1956 on his

plea of not guilty, and, as has been stated, was con

victed and sentenced to ten years imprisonment. Hatt

pleaded guilty on December 14, 1956 to the lesser of

fense of larceny from the person, and, on the recom

mendation of the prosecuting attorney, was sentenced

to five years imprisonment.10

10 The inference is inescapable that Hatt received favorable

consideration because of his testimony against Powell. The

State prosecuting attorney testified in the habeas corpus

hearing before the district court:

“Q. Now, is it your testimony that Hatt did or did not

receive lighter treatment in Birmingham because of his

testimony against Powell?

“A. I—I— I recommended to the court that he be imprisoned

in the penitentiary for a term of five years.

“Q. And what did the court do; did he follow your recom

mendation ?

“A. Yes.”

6 Powell v. Wiman, et al.

Powell v. Wiman, et al. 7

An Alabama statute provides that:

Ҥ307. Testimony of accom plices; must be

corroborated to authorize conviction o f fe lon y .—

A conviction of felony cannot be had on the

testimony of an accomplice, unless corroborated

by other evidence tending to connect the defend

ant with the commission of the offense; and such

corroborative evidence, if it merely shows the

commission of the offense or the circumstances

thereof, is not sufficient.”11

Corroborative evidence to the testimony of Hatt “tend

ing to connect the defendant with the commission of the

offense” consisted of testimony of Powell’s association

with Hatt both before and after the robbery and Mr.

Brown’s testimony that Powell had been employed by

him for about six weeks during the Summer of 1955.

Clearly, Powell could not have been convicted without

Hatt’s testimony. Powell’s conviction or acquittal really

turned upon whether Hatt was a credible witness.

In Alabama, “when a party places a witness on the

stand, he thereby vouches for his credibility.”12 The

State called Hatt as a witness against Powell after Hatt

had pleaded not guilty by reason of insanity. Powell’s

court-appointed attorneys, conscientious, able and dili

gent, but very inexperienced—this was their first jury

trial—attempted repeatedly to bring out Hatt’s mental

condition on cross-examination. To this, the prosecution

vigorously objected.

11 Code of Alabama 1940, Title 15, §307.

12 Equitable Life Assurance Society of U.S. v. Welch, Ala.,

1940, 195 So. 554, 559. See also, Oates v. Glover, Ala.,

1934, 154 So. 786, 787; Jones v. State, Ala., 1897, 22 So.

566; 3 Wigmore on Evidence, §898, pp. 386, et seq.

8 Powell v. Wiman, et al.

“Q. James, have you ever received mental treat

ment?

“A. Yes, sir.

“MR. DEASON [the prosecutor]: Wait a minute,

we object to that, immaterial, incompetent

and illegal.

“MR. COLLINS [Defense]: I think it is.

“THE COURT: Yes, I will sustain it in that form.

“MR. DEASON: Yes, sir.

“MR. COLLINS: You sustain the objection, sir?

“THE COURT: Yes.

“Q................ are you also indicted for this crime?

“A. Yes.

“Q. How did you plead to that charge?

“A. Not guitly by reason of insanity.

“MR. COLLINS: Your honor, I would like to

inquire if they plan to go into his past

psychiatric treatment.

“MR. DEASON: We object to that, this man is

not on trial, just a witness.

“THE COURT: I sustain.

“MR. COLLINS: It is not material to his credi

bility, is that right, sir?

“THE COURT: Just ask your question.

“Q. Do you feel that you are mentally capable

of telling the truth in this case?

“MR. DEASON: Don’t answer that. We ob

ject to that, if the Court please.

“THE COURT: Yes, sustain.

“MR. COLLINS: James, have you had a psy

chiatric examination since you were arrested

for this crime?

“MR. DEASON: Object, don’t answer.”

Powell v. Wiman, et al. 9

The State doggedly and successfully opposed every

effort of the neophyte lawyers to cross examine the

witness as to his insanity. And we might not criticize

the State for so doing if it had not then had further

information, not available to the defendant or his at

torneys, which adversely reflected on Hatt’s sanity.

The State prosecutor had received a letter dated

October 12, 1955, from a Michigan attorney and had

other information to the effect that Hatt had been

confined in mental institutions in three different

states.13 Hatt’s mental condition was a crucial issue.

Evidence of Hatt’s insanity, if not sufficient to establish

his incompetence as a witness, would have gone to the

weight and credibility of his testimony.14 The success

ful effort of the State prosecuting attorney to keep

from the jury what he knew to be substantial evidence

of Hatt’s insanity is not consistent with the high

standard applicable to state prosecuting attorneys, as

well as to United States Attorneys:

“The United States Attorney is the represen

tative not of an ordinary party to a controversy,

but of a sovereignty whose obligation to govern

impartially is as compelling as its obligation to

govern at all; and whose interest, therefore, in a

criminal prosecution is not that it shall win a

case, but that justice shall be done. As such,

he is in a peculiar and very definite sense the

servant of the law, the twofold aim of which is

13 That there was a real question as to H att’s mental con

dition is shown by the fact that the month after Powell’s

conviction Hatt was sent to the Alabama Insane Hospital

for an examination.

14 Redwine v. State, Ala., 1952, 61 So.2d 724, 727; Garrett

v. State, Ala., 1958, 105 So. 2d 541, 547; Hutcherson v. State,

Ala.App., 1958, 108 So. 2d 177, 178.

10 Powell v. Wiman, et al.

that guilt shall not escape or innocence suffer.

He may prosecute with earnestness and vigor—

indeed, he should do so. But, while he may

strike hard blows, he is not at liberty to strike

foul ones. It is as much his duty to refrain

from improper methods calculated to produce

a wrongful conviction as it is to use every

legitimate means to bring about a just one.”15

The evidence goes further, and shows that the State

prosecuting attorney permitted Hatt to testify without

correction to material facts directly contrary to the

written statement which the attorney had previously

taken from Hatt.

Upon cross-examination by Powell’s counsel, Hatt

testified:

“Q. (BY MR. COLLINS:) Now, Jam es, I

believe you said you came to Leeds, Ala

bama, with the defendant, you weren’t

exactly certain when, Friday, Saturday or

Sunday, is that right?

“A. I can’t say when.

“Q. But, you remember going to Leeds, Ala

bama, with the defendant?

“A. Yes.

“Q. But, you don’t know whether it was Sun

day or two days before then or two days

after that?

“A. Well, it was before Sunday.

“Q. It was before Sunday?

“A. Yes.

“Q. Probably Saturday?

“A. Saturday or Friday or somewhere.

15 Berger v. United States, 1935, 295 U.S. 78, 88.

Powell v. Wiman, et al. 11

“Q. Where did you go then, where did you

stay, you probably located yourself some

place?

“A. In the rooming house.

“Q. You went to the rooming house?

“A. Yes.

“Q. Friday or Saturday with the defendant

Powell?

“A. Yes.

“Q. And you didn’t know what time, you didn’t

know whether it was day or night?

“A. No, I don’t remember what it was.

“Q. And then you and the defendant, you

stated, went out and drove by Mr. Brown’s

house, is that correct?

“A. Yes, the Sunday before the robbery I

believe it was.

“Q. After you had been in town a couple of

(sic) three days?

“A. Yes.”

The State did not disclose that it had strong reason

to believe that testimony to be untrue. Yet the State

then had in its possession a written statement from

Hatt that on the Friday and Saturday before he robbed

L. O. Brown on Sunday he had committed two other

armed robberies, the one on Friday in Tampa, Florida,16

18 H att’s statement described the Tampa robbery as follows:

“Q. Did you pull any robberies in Tampa before you left?

“A. Yes.

“Q. Where?

“A. We got $6 off a taxi-cab driver.

“Q. Where was that?

“A. In Tampa. I am pretty sure it was in Tampa.

“Q. Do you know what part of the city that was?

“A. No, I don’t even know that city.

“Q. Do you remember when that was with reference to the

present time, how many days ago?

“A. Week ago last Friday. Today is Friday, isn’t it?

“Q. Yes.

12 Powell v. Wiman, et al.

and the other on Saturday in Montgomery, Alabama.17

According to Hatt’s statement, he met Powell for the

“A. Week ago today.

‘‘Q. You got $6 from him?

“A. Yes.

“Q. How did you get the money?

“A. Well, Bill, he took me— he told me to go to such and

such a corner where he knew— he knew that town, and

I didn’t, and he said he would he there waiting for me,

so, I got a cab and told him to take me to that corner,

and I was pretty tight right then. I couldn’t hardly

walk straight. I called the bartender, and had the

bartender call, and the cab came, and I got there, and

he was there only just a minute, and once I pulled the

gun on him—

“Q. Where was Bill when you pulled the gun on him?

“A. He was parked right behind us about 15 yards, I guess,

parked in a car.

“Q. After you pulled this gun on the taxi-cab driver and

got the money from him, where did you go?

“A. We headed— Bill went and picked up his clothes and

headed out of town. We headed out of town.”

17 H att’s statement described the Montgomery robbery as

follows:

“Q. Where was that?

“A. Montgomery, I believe.

“Q. What did you get there?

“A. $12.

“Q. Who did you rob there?

“A. Cab driver.

“Q. When was that?

"A. Saturday night, I believe it was.

“Q. That was the night before you came into Birmingham?

“A. Yes, sir.

“Q. Where was he when you got the money?

“A. Well, we— he said, ‘get a cab.’

”Q. Who said that?

“A. Bill Powell.

“Q. All right.

“A. He said— I used his suitcase, mostly to make it look

like I was traveling on a bus and was a veteran going

to the Veterans Hospital, and he drove out there and

picked out a place back off the road a little ways, and

I took him— I told him to take me to the Veterans

Hospital, and when he turned around the corner to take

me to the hospital, I told him to drive straight around

into a little grove like. There was trees around, kind

of like a city dump.

“Q. Close to the Veterans Hospital?

“A. Yes, back of it.

“Q. That was last Saturday night?

“A. Yes.

Powell v. Wiman, et al. 13

first time in Tampa just before the Tampa robbery, and

Powell was an accomplice in the Tampa robbery and

in the Montgomery robbery. Hatt’s statement as to

Powell’s participation in those robberies was, of

course, hearsay as against Powell, and would not in

any event have been admissible against Powell on his

prosecution for the robbery of L. O. Brown. However,

when Hatt testified that he had been with Powell at

Leeds, Alabama, on Friday or Saturday, or for two or

three days before the robbery of L. O. Brown on Sunday

the State had good reason to believe that that testimony

was false, and it could not allow it to go uncorrected.

Further, the State knew that Hatt’s admissions con

trary to his testimony were admissions of two armed

robberies which the jury could well have believed to

have a bearing on Hatt’s credibility. Indeed, Hatt’s

admissions in the statement as to his activities earlier

in the week preceding his robbery of L. O. Brown re

flected on his credibility to the n’th degree. According

to his statement in the possession of the State prosecut

ing attorney, Hatt admitted the possession of three

pistols which he had stolen from a gun store in West

Palm Beach, Florida, “a week ago last Tuesday.” He

“Q. Then, when you got out there and stopped, what did

you do?

“A. I told him to strip his clothes off so I could have time

to walk away.

“Q. Did he undress?

“A. He took all but his shoes.

“Q. What did you do with his clothes?

“A. Buried them across the city on the other side of town.

“Q. Do you know about where you buried them?

“A. I don’t know whether it is— there is a state prison you

go by, and I don’t know whether it was on this side or

that side.

“Q. Who was with you when you buried the clothes?

“A. Bill Powell. He covered them up.”

14 Powell v. Wiman, et al.

further admitted that on Wednesday he had held up a

bartender and a woman customer in West Palm Beach

and got $33.00 from them. Hatt stated that no one was

with him on either of those occasions. According to

Hatt’s statement, he had forced the bartender whom he

had robbed to drive him in the bartender’s car about

75 miles on the highway toward Tampa where he “let

him out on the highway to hitch hike back, and I took

the car on a ways further and dropped it off.” At

Tampa, according to the statement, Hatt met Powell,

whom he said he had never seen before.

To summarize, Hatt’s statement, in the possession of

the State’s attorney, admitted that during the week

preceding the robbery of L. O. Brown, Hatt had com

mitted a burglary, and armed robbery, a kidnapping, and

the theft of an automobile before meeting Powell, and

and had committed two other armed robberies with

the claimed assistance of Powell.

While the State was willing to vouch for Hatt’s

credibility, it is extremely doubtful whether the jury

would have agreed if it had been furnished this evi

dence which remained in the exclusive possession of

the State. Not only did the State fail to disclose that

Hatt’s statement contradicted Hatt in a most material

part of his testimony, and reflected on, if it did not

indeed destroy, his credibility, but it affirmatively

represented to the jury that Hatt had told in the

statement the same story that he told on the witness

stand.

Powell v. Wiman, et al. 15

“Q. (BY MR. DEASON:) Now, he has asked

you if you talked to anybody in the solici

tor’s office. I wil ask you if on the 30th

day of September, 1955, if you didn’t make

a complete statement about your activity

in this robbery down at the solicitor’s

office, is that correct?

“A. Yes.

“Q. You remember me down there?

“A. No.

“Q. Asking you certain questions and a man

writing them down?

“A. I can’t say for sure.

“Q. Well, you remember making a statement

down at the solicitor’s office, is that cor

rect?

“A. I remember telling my story.

“Q. In other words, you remember telling your

story the same day you were arrested,

that is correct, isn’t it?

“A. I can’t say for sure whether it was the

same day or not.

“Q. Immediately after, shortly after.

“A. Yes, sir.

“Q. And did you tell the same story then that

you are telling on the witness stand?

“A. Yes.”

Thus the State actually bolstered Hatt’s testimony by

reference to this statement, while keeping the contents

of the statement to itself.

Hatt’s full written statement was first disclosed over

the objection of the State in response to a subpoena

duces tecum issued by the district court in the present

16 Powell v. Wiman, et al.

hearing. As we have heretofore stated, it does not

appear that the Alabama Court of Appeals has had an

opportunity to examine the transcript of evidence in

Powell’s criminal trial. We make these remarks in

justice to that Honorable Court. In the course of its

opinion on Powell’s application for leave to file a writ

of error coram nobis, the Alabama Court of Appeals

said: “We are as zealous as anyone that our peniten

tiaries should confine no one who is innocent.”18 We

know that that is true. Nothing said in this opinion is

meant to reflect upon the Court of Appeals of Alabama.

That Court has had before it practically none of the

evidence now before this Court.

It nonetheless remains true that, as reluctant as a

federal court is to interfere with or upset the judg

ment of a state court, we cannot allow the present

judgment of conviction to stand. Whether or not any

one of the instances which we have recited in which the

State failed to disclose or suppressed evidence going

to Hatt’s credibility would suffice by itself, the totality

of all of them, under the circumstances of this case,

leaves no doubt that Powell’s trial was attended by

such fundamental unfairness as to amount to a denial

of due process of law.

“ . . . it is established that a conviction

obtained through use of false evidence, known

to be such by representatives of the State,

must fall under the Fourteenth Amendment

. . . . The same result obtains when the State,

18 E x Parte Powell, Ala.App., 1958, 102 So.2d 923, 927.

Incidentally, we are not passing on the guilt or innocence

of Powell, but simply on whether his trial met the standards

of due process.

Powell v. Wiman, et al. 17

although not soliciting false evidence, allows

it to go uncorrected when it appears . . . .

“The principle that a State may not know

ingly use false evidence, including false testi

mony, to obtain a tainted conviction, implicit in

any concept of ordered liberty, does not cease

to apply merely because the false testimony

goes only to the credibility of the witness. The

jury’s estimate of the truthfulness and relia

bility of a given witness may well be deter

minative of guilt or innocence, and it is upon

such subtle factors as the possible interest of

the witness in testifying falsely that a defend

ant’s life or liberty may depend . . . .”19

Powell has now been imprisoned for more than five

years. With good time and other allowances, his

sentence will probably expire within less than another

year. The Court’s duty upon a habeas corpus hearing

is to “dispose of the matter as law and justice require.”

28 U.S.C.A. §2243; cf. 28 U.S.C.A. §4106. From the

present record, without more, it would appear that

Powell’s discharge will best serve the ends of justice.

A derhold v. O’Neill, 5 Cir., 1933, 66 F.2d 85; R eid v.

Sanford, N.D. Ga., 1941, 42 F.Supp. 300, 303, 304; 39

C.J.S. Habeas Corpus, Section 102, p. 690, n. 92.

This opinion has, however, gone beyond the findings

of the district court, and even beyond the briefs of

counsel, in elaborating upon the State’s suppression of,

and failure to disclose, vital evidence upon Powell’s

trial. Further, it is still not entirely clear whether

19 Napue v. Illinois, 1959, 360 U.S. 264, 269.

18 Powell v. Wiman, et al.

the State disclosed any evidence to Powell’s counsel

before he was tried and convicted, which is, of course

not shown by the transcript of evidence in his trial.

Under such circumstances, we accord the State an

opportunity to request a further hearing in the district

court, and to make such showing of additional evidence

from which the district court may determine whether

such further hearing is warranted. The district court

will, of course, require that the State act promptly. If

the district court grants any further hearing, then, so

far as is consistent with the rights of the State and of

Powell to introduce all relevant evidence, the district

court will expedite such hearing and the entry of a

final judgment. The judgment of the district court is

reversed and the cause remanded for further proceed

ings consistent with this opinion.

Adm. Office, U.S. Courts— E. S. Upton Printing Co., New Orleans, La.

REVERSED AND REMANDED.

• EDWARD W. WADSWORTH

S. Court of Appeals,Fifth Circuit

'(M YVL^C'L^-------

■ty

New Orleans, Louisiana FEB 2 *