McCleskey v. Zant Brief for Petitioner-Appellee

Public Court Documents

June 26, 1989

81 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McCleskey v. Zant Brief for Petitioner-Appellee, 1989. bef01e66-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/53144d57-0534-4db0-85c5-ea255bc3a9d6/mccleskey-v-zant-brief-for-petitioner-appellee. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

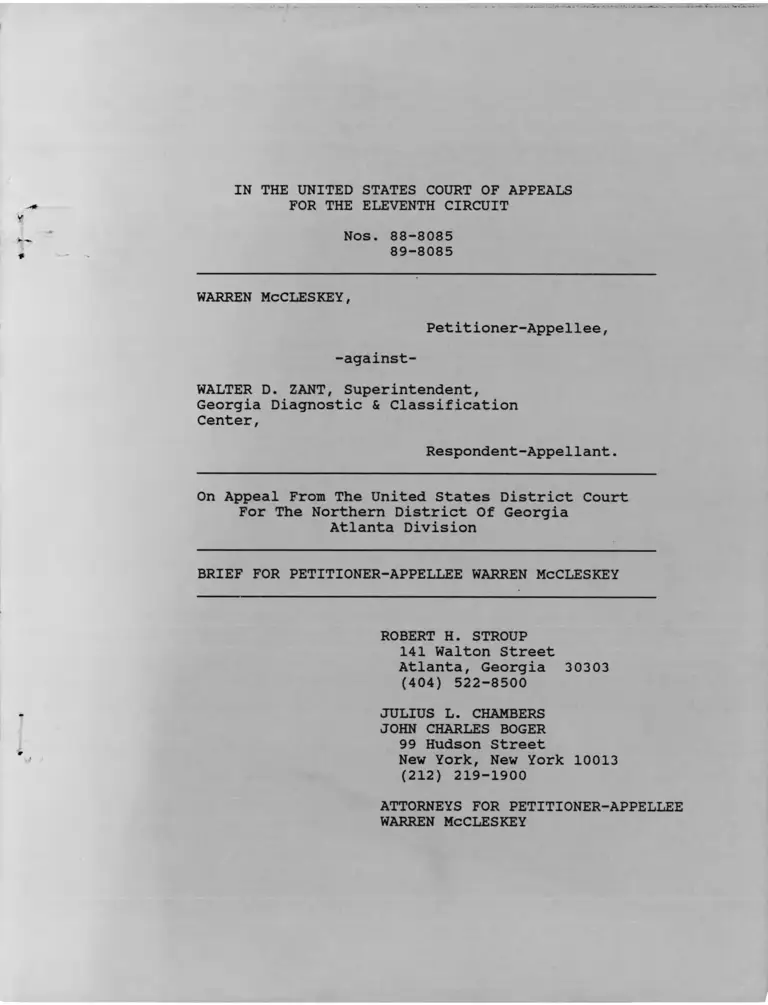

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 88-8085

89-8085

WARREN McCLESKEY,

Petitioner-Appellee,

-against-

WALTER D. ZANT, Superintendent,

Georgia Diagnostic & Classification

Center,

Respondent-Appellant.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Northern District Of Georgia

Atlanta Division

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER-APPELLEE WARREN McCLESKEY

ROBERT H. STROUP

141 Walton Street

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

(404) 522-8500

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

JOHN CHARLES BOGER

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

ATTORNEYS FOR PETITIONER-APPELLEE

WARREN McCLESKEY

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PARTIES

The parties interested in the outcome of this case are the

petitioner-appellee, Warren McCleskey; the trial attorney, John

Turner; the present attorneys for Mr. McCleskey, Robert H.

Stroup, Julius L. Chambers, and John Charles Boger; respondent-

appellant Walter D. Zant; the attorneys for respondent-appellant

Zant, William B. Hill, Jr., Susan V. Boleyn, and Mary Beth

Westmoreland; the trial judge, Hon. Sam McKenzie; and the

District Court judge, Hon. J. Owen Forrester. The victim was

Frank Schlatt.

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT

Petitioner-appellee McCleskey concurs in the request of

respondent-appellant Walter Zant for oral argument in this case,

though not in Warden Zant's reasons for seeking argument. Since

Zant's appeal is, in essence, a multi-faceted attack on the

factfindings of the District Court, and since the relevant

factual record is quite large, including the trial transcript,

the state habeas corpus transcript, the federal habeas corpus

transcript, several depositions, and numerous exhibits, the Court

may well be assisted by the opportunity to question counsel

orally.

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW.............. 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE..................................... 2

(i) Course Of Prior Proceedings........................... 2

(ii) Statement Of Facts................................... 2

I. The State's Allegations Of Abuse Of The Writ.... 3

A. The Defense Effort To Uncover Written Statements 4

1. The Efforts Of Trial Counsel............. 4

2. The Efforts Of Habeas Counsel............ 7

3. The Discovery Of Evans's Written Statement 9

B. The Defense Effort To Locate Massiah Witnesses 10

C. The Findings Of The District Court.......... 13

II. Mr. McCleskey's Claim Under Massiah v. United States 13

A. Background Evidence On the Massiah Claim..... 14

1. Of fie Evans's Testimony At Trial.......... 14

2. Evans's Testimony During State Habeas

Proceedings.............................. 16

B. The Twenty-One Page Statement................. 17

C. The July 8-9, 1987 Federal Hearing............ 19

1. The Testimony Of Prosecutor Russell Parker 19

2. The Testimony Of Police Officers Harris

And Jowers............................... 20

3. The Testimony Of Detective Sidney Dorsey.. 20

4. The Testimony Of Ulysses Worthy.... 22

5. Of fie Evans.............................. 25

D. The August 10, 1987 Federal Hearing.......... 25

1. The Testimony Of Ulysses Worthy.... 25

2. The Testimony Of Deputy Jailor Hamilton... 28

E. The Findings Of The District Court........... 29

III. The Harmless Error Issue......................... 3 0

Page

iii

Page

IV. Warden Zant's Rule 60(b) Motion.................. 33

A. The Issue Of Warden Zant's "Due Diligence"... 33

B. The Materiality Of Offie Evans's Testimony... 35

C. The Findings Of The District Court.......... 3 6

(iii) Statement Of The Standard Of Review................. 37

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT....................................... 38

ARGUMENT.................................................. 42

I. MR. McCLESKEY DID NOT ABUSE THE WRIT OF HABEAS

CORPUS BY FAILING TO UNCOVER THE MISCONDUCT OF

ATLANTA POLICE OFFICERS WHICH CAME TO LIGHT

ONLY IN 1987.................................... 42

A. Warden Zant's Claim Of Deliberate Abandonment... 44

B. Warden Zant's Suggestions Of Inexcusable Neglect. 48

II. THE DISTRICT COURT PROPERLY FOUND THAT ATLANTA

POLICE MISCONDUCT VIOLATED WARREN McCLESKEY'S SIXTH

AMENDMENT RIGHTS UNDER MASSIAH V. UNITED STATES.. 53

A. The District Court's Factual Findings Were Not

Clearly Erroneous Under Rule 52............ 53

B. The District Court Applied The Proper Legal

Standards To The Facts...................... 60

III. THE DISTRICT COURT CORRECTLY FOUND THAT THE

MASSIAH VIOLATION PROVEN IN MR. McCLESKEY' CASE

WAS NOT HARMLESS BEYOND A REASONABLE DOUBT...... 63

IV. THE DISTRICT COURT DID NOT ABUSE ITS DISCRETION

BY DENYING WARDEN ZANT'S RULE 60(b) MOTION FOR

RELIEF FROM JUDGMENT............................ 68

A. Zant,Failed To Show That The Evidence

Is "Newly Discovered"................... 68

B. Zant Failed To Exercise "Due Diligence".. 68

C. There Is No Likelihood That The Proffered

Evidence Would Produce A Different Result 70

CONCLUSION................................................ 72

iv

Cases:

♦Amadeo v. Zant, ___ U.S. ___, 100 L.Ed.2d

249 (1988) 38,42,43,44

♦Anderson v. City of Bessemer City, 470 U.S.

564 (1984) 38,39,43.54

Booker v. Wainwright, 764 F.2d 1371 (11th Cir. 1985) ... 45,48

Brady v. Maryland, 373 U.S. 83 (1963) 4

Brown v. Dugger, 831 F.2d 1547 (11th Cir. 1987) 66

Chapman v. California, 386 U.S. 18 (1967) ............. 65

Fay v Noia, 372 U.S. 391 (1963) ....................... 45,46

Freeman v. State of Georgia, 599 F.2d 65 (5th Cir. 1979) 44

Giglio v. United States, 405 U.S. 150 (1972) 41,63,64,65

Haley v. Estelle, 632 F.2d 1273 (5th Cir. 1980) ....... 48

♦Johnson v. Zerbst, 304 U.S. 458 (1938) 46

Kuhlmann v. Wilson, 477 U.S. 436 (1986) 62

Lightbourne v. Dugger, 829 F.2d 1012 (11th Cir. 1987) .. 61

Maine v. Moulton, 474 U.S. 159 (1985) 62

♦Massiah v. United States, 377 U.S. 201 (1964) passim

McCleskey v. State, 245 Ga. 108, 263 S.E.2d 146 (1980) . 6

Moore v. Kemp, 824 F.2d 847 (11th Cir. 1987) 47,48

Murray v. Carrier, 477 U.S. 478 (1986) ............... 44

Napper v. Georgia Television Co., 257 Ga. 156, 356 S.E.2d

640 (1987) ....................................... 9

Paprskar v. Estelle, 612 F.2d 1003 (5th Cir. 1980) .... 47

Potts v. Zant, 638 F.2d 727 (5th Cir. Unit B 1981) .. 40,45,46,47

Price v. Johnston, 334 U.S. 266 (1948) .............. 40,46

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

v

Ross v. Kemp, 785 F.2d 1467 (11th Cir. 1986) .......... 44

Sanders v. United States, 373 U.S. 1 (1963) .... 40,44,45,47,48

*Satterwhite v. Texas, ___ U.S. ___, 100 L.Ed.2d

284 (1988) 41,64,66

*Scutieri v. Paige, 808 F.2d 785 (11th Cir. 1987 ........ 42,68

Sockwell v. Maggio, 709 F.2d 341 (5th Cir. 1983) 48

United States v. Anderson, 574 F.2d 1347 (5th Cir. 1978) 64

♦United States v. Henry, 447 U.S. 264 (1980) 2,13,62

Walker v. Lockhart, 763 F.2d 942 (8th Cir. 1985) 48

Wong Doo v. United States, 265 U.S. 239 (1924) ........ 47

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. § 2241 ...................................... vii

28 U.S.C. § 2253 ...................................... vii

Rules;

Rule 52, Fed. R. Civ. P............................ 1,38,42,54

Rule 60(b), Fed. R. Civ. P...................... 32,33,35,37,68,

69,70,71

Rule 9(b), Rules Governing Section 2254 Cases........ .. 37,42

Other Authorities:

O.C.G.A. § 50-18-72(a) 9

Restatement of the Lav, 2d, Agency. § 16 .............. 61

Page

✓

vi

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

This is a habeas corpus case filed under 28 U.S.C.

It has been appealed to this Court under 28 U.S.C. § 2253.

vii

2241.

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

Nos. 88-8085

89-8085

WARREN McCLESKEY,

Petitioner-Appellee,

-against-

WALTER D. ZANT, Superintendent,

Georgia Diagnostic & Classification

Center,

Respondent-Appellant.

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Northern District Of Georgia

Atlanta Division

BRIEF FOR PETITIONER-APPELLEE WARREN McCLESKEY

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

1. Are the District Court's factual findings (i) that Mr.

McCleskey did not deliberately abandon his constitutional claim

under Massiah v. United States. 377 U.S. 201 (1964), (ii) that

his failure to have uncovered evidence of the Massiah violation

earlier was not a result of "inexcusable neglect," and (iii) that

he did not otherwise abuse the writ, clearly erroneous under Rule

52?

2. Are the District Court's factual findings concerning Mr.

McCleskey's Massiah claim, (i) that Atlanta police officers

arranged to have an informant moved into an adjacent cell, (ii)

that they instructed the informant to question McCleskey

surreptitiously, and (iii) that the informant actively

interrogated McCleskey on behalf of the police, clearly

erroneous?

3. Do the facts found by the District Court establish a

violation of Mr. McCleskey's Sixth Amendment rights under Massiah

v. United States and United States v. Henrv. 447 U.S. 264 (1980)?

4. On the present factual record, did the District Court

err in concluding that the Massiah violation was not harmless

beyond a reasonable doubt?

5. When a respondent, here Warden Walter Zant, moves to

reopen a final judgment under Rule 60(b) in order to submit

evidence that is not "newly discovered," when his own submissions

demonstrate that he has exercised no diligence in obtaining that

evidence earlier, and when the District Court has entered factual

findings that the proffered evidence would not likely affect the

judgment, is it an abuse of discretion for the District Court to

deny motion?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

(i) Course of Prior Proceedings

Mr. McCleskey accepts the general description of the prior

proceedings set forth by Warden Zant.

(ii) Statement of Facts

Four legal issues are presented by this appeal: (i) possible

abuse of the writ; (ii) the merits of Mr. McCleskey's Massiah

claim; (iii) whether the Massiah violation was harmless beyond a

reasonable doubt; and (iv) whether the District Court properly

2

denied Warden Zant's motion to reopen the judgment under Rule

60(b) .

Warden Zant's primary contention is that the principal

factfindings of the District Court were clearly erroneous on each

issue. To evaluate Zant's contentions, an extensive review of

the facts is necessary. Our statement will address: (i) the

circumstances under which the present Massiah claim first came to

the attention of Mr. McCleskey's counsel; (ii) the evidence of

the Massiah violation; (iii) a description of the evidence

presented to Mr. McCleskey's 1978 jury on the murder charge; and

(iv) the circumstances surrounding Warden Zant's motion to reopen

the District Court's judgment in 1988.

I. The State1s Allegations Of Abuse Of The Writ

At the heart of the Massiah claim presented by Mr. McCleskey

in his second federal petition, the District Court noted (R3-22-

15, 19), are two items of evidence: the testimony of jailor

Ulysses Worthy, "who was captain of the day watch at the Fulton

County Jail during the summer of 1978 when petitioner was being

held there awaiting his trial. . . ." (R3-22-15) ; and a 21-page

typewritten statement by Offie Evans — an informant and chief

witness against Mr. McCleskey — given to State authorities on

August 1, 1978. (See Rl-1, Exhibit E; Fed. Exh. 8). 1 To resolve

1 Each reference to an exhibit admitted into evidence by

the District Court during the July and August, 1987 federal

hearings will be indicated by the abbreviation "Fed. Exh."

followed by the exhibit number and, where relevant, the page number of the exhibit.

3

the issue of abuse of the writ, this Court must review when, and

under what circumstances, those two items came to the attention

of Mr. McCleskey's counsel.

A. The Defense Effort To Uncover Written Statements

1. The Efforts of Trial Counsel

Prior to Mr. McCleskey's trial in 1978, Assistant

District Attorney Russell Parker provided McCleskey's trial

attorney, John Turner, with access to most of his file (Fed. Exh.

3, 4-8) — except for certain grand jury minutes and, unknown to

Turner, the 21-page statement by Offie Evans at issue here (which

contained numerous verbatim statements and admissions ostensibly

made by Mr. McCleskey to Evans while both were incarcerated in

the Fulton County Jail in July of 1978.)

To assure himself that he had obtained all relevant

evidence, defense attorney Turner filed one or more pretrial

motions under Brady v. Maryland. 373 U.S. 83 (1963), seeking all

written or oral statements made by Mr. McCleskey to anyone, and

all exculpatory evidence.2

After conducting an in camera review, the trial court denied

2 Although the District Court held that the copies of

Turner's Brady motions proffered in Mr. McCleskey's federal

petition (see Rl-1, Exhibit M) had not been properly

authenticated, (R4- 73-81), Warden Zant conceded, and the

District Court found, "that a reguest was made for statements,

which is necessarily implied from the action of the trial

court."(Id. 78). Later during the federal hearing, copies of

Turner's Brady motions, which had been signed and received by the

District Attorney, were discovered in the District Attorney's

files. Warden Zant stipulated to these facts at the August 10th federal hearing. (R6-118).

4

Mr. Turner's motion, holding without elaboration that any

evidence withheld by prosecutor Parker was "not now subject to

discovery." (Fed. Ex. 5). The trial court's order contained

absolutely nothing to indicate that among the evidence withheld

was any written statement by Offie Evans. In fact, prosecutor

Parker later acknowledged that he never informed Turner about

the nature or content of the items submitted to the trial court

for in camera inspection. (Fed. Ex. 3, 15).3

At trial, during the State's cross-examination of Mr.

McCleskey, defense counsel Turner once again sought to determine

whether any statements implicating his client had been obtained

by the State:

MR. TURNER: Your Honor, I think that from the

direction of things from what Mr. Parker is saying it

appears that he must have some other statements from the

defendant. I asked for all written and oral statements in

my pre-trial motions. If he has something he hasn't

furnished me, I would object to getting into it now.

THE COURT: Well, he has a statement that was furnished

to the Court but it doesn't help your client.

MR. TURNER: I am not dealing with that part of it. Iam saying I asked him —

MR. PARKER: It's not exculpatory.

THE COURT: You are not even entitled to this one.

MR. TURNER: I am entitled to all statements he made.

That is what the motion was filed about.

3 In a deposition taken by Mr. McCleskey's counsel during

state habeas proceedings, prosecutor Parker testified as follows:

"[T]he morning of the trial, as I recall, John Turner . . .

wanted to know what the matters were at that time that the judge

had made an in camera inspection of. Of course, I told him I

couldn't tell him; no sense in having an in camera inspection if I was going to do that." (Fed. Exh. 3, at 15).

5

THE COURT: This is not a statement of the defendant.

MR. TURNER: We are not talking about a statement of

the defendant.

THE COURT: I don't know that we are talking about any

written statement.

MR. TURNER: I am saying I filed for oral and written

statements. I asked for all statements of the defendant.

THE COURT: Let the record show I wrote you and made it

of record. It is not admissible and what he is doing is in

the Court's opinion proper.

(Rl-1, Exhibit 0, 830-832; see Fed. Ex. 6)(emphasis added)).

The trial court thus not only denied this second defense

request; it affirmatively, and inexplicably, stated, "I don't

know that we are talking about any written statement," (id. 831),

suggesting that no written statement existed at all.

On appeal to the Supreme Court of Georgia, Turner contended

that the State's refusal at trial to turn over Mr. McCleskey's

statements, contained in what Turner plainly believed to have

been an oral statement by Offie Evans to police, had violated Mr.

McCleskey's rights. The Georgia Supreme Court denied the claim

and upheld the State's position, explicitly stating in its

opinion that "[t]he evidence [the defense counsel] sought to

inspect was introduced to the ~iurv in its entirety." McCleskev v.

State, 245 Ga. 108, 263 S.E.2d 146, 150 (1980) (emphasis added).

Thus, trial counsel, although unaware of the 21-page

typewritten statement of Offie Evans, made at least three

separate attempts to obtain all relevant statements from the

State: not only were all denied, but the trial court and the

6

Georgia Supreme Court implied that no written statement existed

or that, if one did, it was introduced to the jury in its

entirety. As John Turner testified during state habeas

proceedings, "I was never given any indication that such a

statement existed." (St. Hab. Tr. 77).

2. The Efforts Of Habeas Counsel

Mr. McCleskey's present counsel, Robert Stroup, testified

that, from his review of the trial and appellate proceedings, he

drew the inference that no written statement of Offie Evans

existed, but only an "oral statement . . . introduced in its

entirety through Evans' testimony at trial." (Rl-7-2; Fed. Exh.

1; see also id., at 8; R4-45) . Nevertheless, Mr. Stroup sought

to review again the prosecutor's investigative file. During the

prosecutor's deposition, he obtained an agreement for production

of "the entire file" made available to defense counsel (Fed. Exh.

3, 4-6), unaware that any written document had been withheld from

trial counsel. (Rl-7- 8-9).

Subsequently the Assistant Attorney General handling the

case mailed to Mr. Stroup and the court reporter a large number

of documents, reciting in his transmittal letter that he was

"felnclosfinal ... a complete copy of the prosecutor's file

resulting from the criminal prosecution of Warren McCleskey in

Fulton County." (Fed. Exh. 7) (emphasis added). The 21-page

written statement of Offie Evans was not included. (Rl-7-3; Fed.

Ex. 2) . Relying on that representation, Mr. Stroup has since

testified, it did not occur to him that any written statement

7

existed. (Rl-7-10).

Prosecutor Parker did make one oblique reference to such an

item during his state habeas deposition. The exchange in

question began with a question by Mr. Stroup, obviously premised

on the assumption that Evans had given police only an oral

statement: "Okay. Now, I want to direct your attention to a

statement from Offie Evans that was introduced at Warren

McCleskey's trial." (Pet. Ex. 3, at 8). The prosecutor

responded, "Okay. When you referred to a statement, Offie Evans

gave his statement but it was not introduced at the trial. It

was part of that matter that was made in camera inspection by the

judge prior to trial." (Id.) Mr. Stroup immediately replied.

"All right. Let me make clear what my question was, then. Offie

Evans did in fact give testimony at the trial — let me rephrase

it. When did you learn that Offie Evans had testimony that you

might want to use at trial?" (Id.)

Mr. Stroup has subsequently averred that

Parker's comment, at page 8 of the deposition, ... was

not directly responsive to my question, and I thought

he misunderstood my question. I do not believe I

actually understood what he said in response to my

question, and I rephrased the question to make certain

that he understood me. When the deposition transcript

became available to me for review, I already had

[Assistant Attorney General] Nick Dumich's letter

reflecting his understanding that what we were dealing

with was a complete copy of the prosecutor's file. It

never occurred to me at this stage in the proceedings

that there was a written statement from Offie Evans

that the State had not produced.

(Rl-7, 9-10).

After reviewing the sequence of events, the District Court

8

found:

The statement was clearly important. It arguably has

favorable information. It wasn't turned over. I don't

think that there's anything — the only thing frankly

that clearly indicates that Mr. Stroup should have

known there was a statement is Russ Parker's one

comment in the habeas, and it is clear to me that Mr.

Stroup didn't understand what was told him.

The question gets to be maybe in a rereading of the

deposition maybe he should have seen it or that sort,

but I don't think that it would be proper to let this

case go forward with such suggestions [as] ... are

raised by that statement ... So I will allow the

statement to be admitted into evidence on the merits.

(Rl, 118-19). In its subsequent written order, the District

Court explicitly reaffirmed that "petitioner's counsel's failure

to discover Evans' written statement was not inexcusable

neglect." (R3-22-25).

3. The Discovery Of Evans's Written Statement

Offie Evans's 21-page statement first came to light in June

of 1987, following a fortuitous development on May 6, 1987, in

an unrelated Georgia case, Napper v. Georgia Television Co.. 257

Ga. 156, 356 S.E.2d 640 (1987), which appeared to hold, for the

first time, that police investigative files would be deemed

within the compass of the Georgia Open Records Act, O.C.G.A. §

50-18-72(a). Mr. Stroup immediately cited that then-recent

decision, still pending before the Georgia Supreme Court on

rehearing, in support of a request to the Atlanta Bureau of

Police Services for the police files in McCleskey's case. (Rl-7-

6) . Because of the pending rehearing, attorneys for the Atlanta

Bureau were reluctant to disclose the police file, but on June

9

10, 1987, they agreed to provide Mr. Stroup with one document—

which proved to be the 21-page statement made by Offie Evans.

(Rl-7-7). Mr. McCleskey subsequently made that document the

centerpiece of the Massiah claim included in his second federal

petition. (See Rl-9 & Exh. E).

B. The Defense Effort To Locate Massiah Witnesses

Mr. Stroup has acknowledged that, at the outset of Mr.

McCleskey's initial state habeas proceedings, he had an

unverified suspicion that Offie Evans may have been a police

informant. (R4-31). Although Stroup lacked hard evidence to

support his suspicion, in an abundance of caution, he pled a

Massiah v. United States claim in an amendment to Mr. McCleskey's

initial state habeas petition. (R4-36).

Mr. Stroup followed up his suspicions with extensive

investigations during state habeas corpus proceedings. He first

spoke with certain "Atlanta Bureau of Police Services officers"

who had been his clients in earlier Title VII litigation, and

obtained information from them on how best to pursue the

prospect of an informant relationship. (R4- 31-32) Following

their lead, Stroup spoke with "two people [at the Fulton County

Jail] who were specifically identified to me as people who might

have information." (R4-33).4 These jailors, however, proved to

4 Stroup elaborated his understanding that he "was

speaking to people at Fulton County Jail who were directly

involved with Offie Gene Evans. . . There was a gentleman named

Bobby Edwards who by that time had left the Fulton County

Sheriff's Department . . . He had by that time moved to Helen,

Georgia or thereabouts . . . and I was able to find him through a

10

have no information "regarding how Evans came to be assigned to

the jail cell that he was assigned to or of any conversations

with the . . . detectives regarding Offie Evans' assignment to

that jail cell." (R4-33).

Mr. Stroup did not conclude his investigation with these

jailor interviews. Instead, he specifically sought to uncover

evidence of a Massiah violation during the deposition of

prosecutor Parker. Mr. Stroup twice asked Parker about

relationships between Offie Evans and the State:

Q. [Mr. Stx*oup] : Okay. Were you aware at the time of

the trial of any understandings between Evans and any

Atlanta police department detectives regarding

favorable recommendation [sic] to be made on his

federal escape charge if he would cooperate with this

matter?

A. [Mr. Parker]: No, sir.

Q. Let me ask the question another way to make sure we

are clear. Are you today aware of any understanding

between any Atlanta police department detectives and

Offie Evans?

A. No, sir, I'm not aware of any.

(Fed. Exh. 3, 9-10).5

On cross-examination, prosecutor Parker broadened his

testimony:

Q. Do you have any knowledge that Mr. Evans was

working as an informant for the Atlanta Police or any

police authorities when he was placed in the Fulton

realtor who I know up in that area." (R4- 48-49).

5 Warden Zant clearly overlooked these questions when he

asserted that "the only question asked of Mr. Parker relating to

any type of Massiah claim was asked by the assistant attorney

general and Mr. Stroup simply failed to ask any questions

whatsoever concerning this issue." (Resp. Br. 31).

11

County Jail and when he overheard these conversations

of Mr. McCleskey?

A. I don't know of any instance that Of fie Evans had

worked for the Atlanta Police Department as an

informant prior to his overhearing conversations at the

Fulton County Jail.

(Fed. Exh. 3, 14-15). On redirect examination, Mr. Stroup once

again sought, without success, information from Parker on

possible deals with, or promises made to, Offie Evans. (See Fed.

Exh. 3, 18-20).

Mr. Stroup subseguently explained that he did not carry Mr.

McCleskey's Massiah claim forward into his initial federal

petition, because he had been unable factually to substantiate

it during state habeas proceedings:

... I looked at what we had been able to develop in

support of the claim factually in the state habeas

proceeding and made the judgment that we didn't have

the facts to support the claim and, therefore, did not

bring it into federal court.

(R4- 44).

As indicated above, when Mr. McCleskey filed his second

federal petition, he relied primarily upon Offie Evans's 21-page

statement to support his Massiah claim. (see Rl-1, 7-13).

Petitioner had not yet discovered Ulysses Worthy, who had

retired from the Fulton County Jail in 1979, and whose appearance

on July 9, 1987 , during the federal hearings, was the

serendipitous result of a massive, indiscriminate effort during

to subpoena everyone whose name was mentioned in any document

uncovered by counsel during the July 8-9th federal hearings. (R4-

21) .

12

C. The Findings Of The District Court

After receiving the documentary evidence and hearing live

testimony from Robert Stroup, Russell Parker, and the Atlanta

detectives, the District Court made comprehensive findings on the

issue of abuse, excerpted as follows:

Although petitioner did raise a Massiah claim in his

first state petition, that claim was dropped because it

was obvious that it could not succeed given the then-

known facts. At the time of his first federal

petition, petitioner was unaware of Evans' written

statement. . . This is not a case where petitioner has

reserved his proof or deliberately withheld his claim

for a second petition. . . . Here, petitioner did not

have Evans' statement or Worthy's testimony at the time

of his first federal petition; there is therefore no

inexcusable neglect unless "reasonably competent

counsel" would have discovered the evidence prior to

the first federal petition. This court [has] concluded

. . . that counsel's failure to discover Evans' written

statement was not inexcusable neglect. [R4-118-119].

The same is true of counsel's failure to discover

Worthy's testimony. . . [C]ounsel did conduct an

investigation of a possible Massiah claim prior to the

first federal petition, including interviewing "two or

three jailers." . . . The state has made no showing of

any reason that petitioner or his counsel should have

known to interview Worthy specifically with regard to

the Massiah claim.

(R3-22- 24-25).

II. Mr. McCleskev's Claim Under Massiah v. United States

Mr. McCleskey's constitutional claim under Massiah and Henry

is straightforward: that Offie Gene Evans, one of the principal

witnesses employed by the State at McCleskey's 1978 trial, "was

acting on behalf of the State as an informant in the Fulton

County Jail" when he secured a series of post-indictment

admissions from Mr. McCleskey (Rl-1-7), and that the State's use

of Evans's testimony, detailing those admissions, against Mr.

13

McCleskey at his trial violated his Sixth and Fourteenth

Amendment rights to the assistance of counsel in post-indictment

encounters with State authorities or their agents. (Id; see also

Rl-1- 7-13) .

The principal evidence of the Massiah violation was

presented during three days of federal habeas corpus hearings in

July and August of 1987. The cornerstones of McCleskey's case,

as indicated, were (i) the 21-page, typewritten statement, given

by Offie Evans to Fulton County prosecutor Russell Parker and two

Atlanta policemen on August 1, 1978, and (ii) the lxve testimony

of Ulysses Worthy.

The full significance of these two items, however, appears

only in light of background evidence that was developed during

Mr. McCleskey's 1978 trial and during state habeas corpus

proceedings. That background evidence will be set forth first,

before turning to the contents of the statement and Worthy's

testimony.

A. Background Evidence On The Massiah Claim

1. Offie Evans's Testimony At Trial

Although a number of witnesses at Mr. McCleskey's trial

testified that McCleskey had participated in an armed robbery of

the Dixie Furniture Store in Atlanta, Georgia, on May 13, 1978,

the State produce no witnesses to the shooting of Atlanta police

officer Frank Schlatt, which occurred as Schlatt entered the

furniture store in response to a silent alarm. The murder weapon

itself was never recovered.

14

To prove that Mr. McCleskey had personally committed the

homicide against Officer Schlatt, the State relied on partially

contradictory testimony about who had been carrying the murder

weapon.6 The State also relied on two witnesses, both of whom

claimed that McCleskey had confessed to them, after the crime,

that he had shot Officer Schlatt. One of the two witnesses was

the most likely alternative suspect in the shooting — Ben

Wright, McCleskey's co-defendant and a dominant actor in planning

and executing the armed robbery. (See Tr. T. 651-657).

Apart from Wright, the only witness offering direct

testimony that Mr. McCleskey had been the triggerman was Of fie

Gene Evans, who told the jury that McCleskey had admitted

committing the homicide during conversations in the Fulton County

Jail, where the two were in adjacent cells. Evans in fact gave

important testimony on three points: (i) he told the jury about

McCleskey's "confession" (Tr. T. 870-871; Fed. Exh. 4, 870-871);

(ii) he alleged that McCleskey had "said . . . he would have

tried to shoot his way out . . . if it had been a dozen" police

6 One of the four robbers, Mr. McCleskey's co-defendant Ben

Wright, and several other witnesses, testified that McCleskey may

have been carrying a pearl-handled, silver .38 pistol linked to

the homicide. (Tr. T. 649; 727). Yet on cross-examination, Ben

Wright admitted that he, not McCleskey, had personally been

carrying that weapon for several weeks prior to the crime. (Tr.

T. 682) .

Moreover, Ben Wright's girlfriend admitted that she had

informed police, on the day Wright was arrested, that Wright, not

McCleskey, had been carrying the .38 pistol the day of the

furniture store robbery. During trial, she attempted to change

that testimony, conforming her story to that of her boyfriend

Wright, and claiming that McCleskey had taken the .38 pistol on the morning of the crime. (Tr. T. 607; 631-634).

15

officers" (Tr. T. 871; Fed. Exh. 4, 871) ;7 and (iii) he single-

handedly clarified a glaring inconsistency in the identification

testimony of one of the State's principal witnesses, explaining

that Mr. McCleskey had acknowledged wearing makeup and a disguise

during the crime. (Tr. T. 301-303; 870-871; 876-879).

On both direct- and cross-examination, Offie Evans denied

that his testimony was being given in exchange for any promise or

other consideration from State officials. (Tr. T. 868-869; 882-

883) .

2. Evans's Testimony During State Habeas Proceedings

During the course of Mr. McCleskey's 1981 state habeas

proceedings, Offie Evans took the witness stand a second time.

Evans acknowledged that he had engaged in several interviews

with State officers prior to Mr. McCleskey's trial; the first,

with Atlanta police detectives Welcome Harris and Sidney Dorsey

(St. H. Tr. 117; Fed. Exh. 16, 117); and a second, with

prosecutor Russell Parker. (St. H. Tr. 118; Fed. Exh. 16, 118).8

7 This ostensible statement subsequently became a basis for

the prosecutor's argument to the jury that Mr. McCleskey had

acted with "malice." (See Tr. T. 974).

8 Offie Evans's testimony unmistakably confirms that there

were two separate interviews:

Q. All right. You talked with Detective Dorsey — it

was Dorsey, the Detective you talked to?

A. That's right.

Q. All right. And you talked with Detective Dorsey

first before you talked with Russell Parker from the

D.A.'s Office?

A. That's right.

16

In response to a question by the state habeas court, Evans

revealed that he had testified against Mr. McCleskey at trial in

exchange for a offer of assistance with criminal charges pending

against him in 1978:

THE COURT: Mr. Evans, let me ask you a question. At

the time that you testified in Mr. McCleskey's trial,

had you been promised anything in exchange for your

testimony?

THE WITNESS: No, I wasn't. I wasn't promised nothing

about — I wasn't promised nothing by the D.A. but the

Detective told me that he would — he said he was going

to do it himself, speak a word for me. That was what

the Detective told me.

BY MR. STROUP: Q. The Detective told you that he

would speak a word for you?

A. Yeah.

Q. That was Detective Dorsey?

A. Yeah.

(St. H. Tr. 122; Fed. Exh. 16, 122).

B. The Twenty-One Page Statement

The 21-page statement of Offie Evans, annexed by Mr.

McCleskey to his second federal petition, purports to be an

account of (i) short snippets of conversations, overheard by

Offie Evans, between McCleskey and a co-defendant, Bernard

Dupree, and (ii) a long series of direct conversations between

Evans and McCleskey, initiated on July 9, 1978, while all those

involved were incarcerated in adjacent cells at the Fulton

County Jail. (See Fed. Exh. 8; see also Rl-1, Exhibit E).

(St. H. Tr. 119; Fed. Exh. 16, 119).

17

The typewritten statement reveals that, once in an adjacent

cell, Evans disguised his name, falsely claimed a close

relationship with McCleskey's co-defendant Ben Wright, lied about

his own near-involvement in the crime, spoke to McCleskey about

details of the crime which had not been made public and which

were known only to Atlanta police and to the participants,9

established himself with McCleskey as a reliable "insider," and

then began systematically to press McCleskey for information

about the crime.10

9 For example, Evans accurately suggested that he knew that

McCleskey and other co-defendants had told police that co

defendant Ben Wright was the likely triggerperson (Fed. Exh. 8,

at 4) although this fact had not been made public in July of 1978.

10 In his typewritten statement to prosecutor Russell

Parker, Evans frankly confessed to his duplicity in dealing with

Mr. McCleskey:

"I told Warren McClesky [sic] 'I got a nephew man, he in a

world of trouble . . . ' McClesky asked me 'What is his name.1 I

told him 'Ben Wright.' McCleskey said 'You Beens' [sic] uncle.' I

said 'Yeah.' He said 'What's your name?' I told him that my name

was Charles." (Fed. Exh. 8, at 3). After Evans falsely assured

McCleskey that he "used to stick up with Ben," and that "Ben told

me that you shot the man yourself," ( id. at 4), Evans began to

pry open the story of the crime. "I said man 'just what's

happened over there?" (Id.)

Even after McCleskey told him some details of the crime,

Evans continued his surreptitious interrogation: "And then I

asked McClesky what kind of evidence did they have on him." ( Id.

at 6) . In a subsequent conversation, Evans sought to learn the

location of the missing murder weapon: "Then I said, 'They ain't

got no guns or nothing man?"' (Id. at 7). When Bernard Dupree,

Mr. McCleskey's co-defendant, overheard the conversations between

Evans and McCleskey from his cell upstairs and became

apprehensive, Evans worked to allay Dupree's suspicions, "talking

to Dupree about Reidsville [and] just about ma[king] Dupree know me himself." (Id. at 9).

18

C. The July 8-9. 1987 Federal Hearing

1. The Testimony of Prosecutor Russell Parker

During the federal hearing on July 8 and 9, 1987, Russell

Parker and three Atlanta police officers assigned to the Schlatt

homicide case in 1978 gave testimony concerning the Massiah

claim. Russell Parker testified that he met with Offie Evans, in

the presence of Atlanta police officers, on two occasions, first

at the Fulton County Jail on July 12th, 1978, and then again on

August 1, 1978, when the 21-page statement was transcribed. (R4-

140-141). However, Parker insisted: (i) that Offie Evans had

told them everything eventually reflected in the 21-page,

typewritten statement during the initial, July 12th interview

(R4-152) ; (ii) that he had not engaged in conversations with

Of fie Evans prior to July 12th (R4-140) ; and (iii) that he had

not asked Evans on July 12th, or prior thereto, to serve as an

informant. (R4- 166-167).

Russell Parker's testimony seems largely borne out by his

contemporaneous notes of the July 12th meeting, which include

several notations consistent with key portions of the

typewritten statement Evans gave a month later. (See Fed. Exh.

9) •

Russell Parker testified emphatically that he had neither

met nor even heard of Evans prior to their July 12th meeting.

(R4-142; R5- 85-86; R6-109). Indeed, Parker apparently conducted

an informal investigation into Evans's background after their

July 12th meeting. Written notes by Parker, dated July 25, 1978,

19

reflect that Parker heard from several independent sources—

among them Federal Corrections official Frank Kennebrough and FBI

agent David Kelsey — that Evans was "a good informant," whose

evidence was "reliable." (Fed. Exh. Ex. 10; see also R6- 81-82).

Another federal correctional official, E.W. Geouge, described

Offie Evans as "[a] professional snitch" whose word, however, had

to be "take[n] with a grain of salt." (Id.)

2. The Testimony Of Police Officers Harris and Jowers

Two other police officers who had investigated the

McCleskey case, Welcome Harris and W. K. Jowers, testified that

they likewise had not known Evans prior to July 12, 1978. (R4-

200) . Officer Jowers, who was not present at the July 12th

meeting with Evans, testified that he never came into contact

with Offie Evans during the McCleskey investigation. (R5- 35-36).

Both Harris and Jowers testified that they had never met

privately with Offie Evans or asked him to serve as an informant

against Warren McCleskey, and that they had never directed Evans

to seek admissions from McCleskey. (R6- 98-99, 102-102)

3. The Testimony of Detective Sidney Dorsey

The third police officer on the case, Sidney Dorsey, told a

different story. Dorsey acknowledged that he had previously

known Evans (R5-49) , and that he was aware that Evans had

previously served as an informant. (R5-53). Indeed, Dorsey

himself had personally used Evans as am informant in other cases.

(Id.) Detective Dorsey testified that

20

Q. ... [H]e was the person over the years that

would provide occasionally useful information

to the department?

A. He has — he has — he has on occasions that

I can recall been cooperative with me.

Q. Right. And so when he called you'd come see

him because it might well be the prospect of

some information?

A. Yeah, yeah. I'd see him or hear from him

from time to time. ... [H]e was the kind of

person that if he called me I'd go see him.

(R5- 53, 52).

Despite this pre-existing special relationship with Offie

Evans, Detective Dorsey professed a total lack of memory

concerning his dealings with Evans during the Schlatt

investigation:

Q. Okay ... [Evans] found himself in the Fulton County

Jail in July of 1978. Did you go see him at any point

in July?

A. Counselor, I do not recall going to see Offie Evans at

the Fulton County Jail during that time or any time.

Q. Do you remember any meetings that might have been held

between Mr. Evans and yourself and Detective Harris and

Russell Parker at the jail?

A. Counselor, in all honesty, I do not.

* * * *

A. I'm not suggesting that the meeting didn't take place,

nor am I suggesting that I wasn't there. I just don't

recall being there and for some reason no one else

remembers my being there either.

(R5- 57-58, 59-60).

As the excerpt above reveals, Detective Dorsey was unwilling

to deny categorically during the July and August, 1987 hearings

21

that he had met with Evans during the Schlatt investigation. On

the contrary, he acknowledged that he "probably did" meet with

Evans (R5-60) , that it was "very possible" he had done so. (R5-

66). He simply could not remember.

Detective Dorsey did clearly remember, however, that he had

not shared knowledge of his special relationship with Evans

widely, not even with the other Atlanta police officers on the

Schlatt case. (R5-55; 61-62). Officers Harris and Jowers

confirmed that they had not known of Detective Dorsey's prior

informant relationship with Offie Evans. (R4-200; R5- 35-38).

Moreover, all of the other participants testified that their

recollections concerning Officer Dorsey's role in the Schlatt

investigation were very hazy, at best. Russell Parker testified

that he had no recollection of Detective Dorsey's role at all

(R4-131; R6-113), and more specifically, he did not remember

Dorsey's presence at the July 12, 1978 meeting, even though his

own notes indicate that Dorsey attended that meeting. (R4-131;

R6-113; Fed. Exh 9, at 4).

Detective Harris likewise testified that he had only a

"vague recollection" at most of Detective Dorsey's involvement in

the investigation. (R4-206; id. 195; R6-107). Detective Dorsey

explained that "generally we all sort of worked on our own.

There was very seldom, if any, orders ever given." (R5 -48-49).

4. The Testimony Of Ulysses Worthy

Late in the afternoon of the second day of the federal

hearing in July of 1987, Ulysses Worthy answered one of many

22

subpoenas that had been served by Mr. McCleskey's counsel on a

wide variety of state, county, and municipal officers during the

course of the two-day hearing. After a momentary interview with

counsel for Mr. McCleskey and Warden Zant (R6- 50-52; R6- 118-

119), Worthy took the stand.

Mr. Worthy testified that he had been the captain of the day

watch at the Fulton County Jail in 1978. (R5-146) . He recalled

that Offie Evans was in custody during that time. (R5-147). He

also recalled a meeting, which took place in his presence at the

Fulton County Jail, between several Atlanta police officers and

Offie Evans. (R5-147-149).

During this meeting,11 Detective Sidney Dorsey and Offie

Evans discussed the murder of Officer Schlatt (R5-148), and

Worthy recalled that Detective Dorsey (or perhaps some other

"officer on the case") requested Evans "to engage in

conversations with somebody . . . in a nearby cell." (R5- 148-

149) . Mr. Worthy testified that the targeted inmate was Warren

McCleskey, who was being held in isolation awaiting trial

following his indictment for murder and armed robbery. Mr.

Worthy confirmed, upon further questioning, that an Atlanta

police officer "asked Mr. Evans to engage in conversations with

McCleskey who was being held in the jail." (R5-150).

Worthy testified that, as captain of the day watch, he had

occasionally received other requests from Atlanta police

11 Mr. Worthy indicated that the detectives "were out

several times" to meet with Offie Evans. (R5-151).

23

/

officers, which he would honor, to place one inmate in a cell

next to another so that police could obtain information on

pending criminal cases. (R5-152). In the McCleskey case, Worthy

specifically recalled that "[t]he officer on the case," made such

a request to him. (R5-153). In response to the police officer's

request, Offie Evans was moved from another part of the Fulton

County Jail to a cell directly adjacent to Warren McCleskey's

cell:

Q. [By the State]: Mr. Worthy, let me see if I

understand this. Are you saying that someone

asked you to specifically place Offie Evans

in a specific location in the Fulton County

Jail so he could overhear conversations with

Warren McCleskey?

A. Yes, ma'am.

(R5-153). As Mr. Worthy later explained to the District Court:

Judge, may I clarify that? . . . in this

particular case this particular person was

already incarcerated. They just asked that

he be moved near where the other gentleman

was.

(R5-155).12

12 Mr. Worthy's account of an initial meeting between

Detective Dorsey and Offie Evans, followed by Evans' move to a

cell next to McCleskey, followed by Evans' extensive

conversations with Mr. McCleskey, culminating in Evans' meeting

with Parker and Atlanta police officers, helps to explain one

major puzzle about the basic structure and content of Evans' 21-

page written statement. Although Evans was arrested and taken to

the Fulton County Jail on July 3, 1978 (R5- 101-17), his written

statement is absolutely silent concerning any contact with

McCleskey during the four-day period between July 3rd and July

8th. Only beginning on the 8th of July does Evans' statement

first begin to report any conversations between McCleskey and his

partner Bernard Dupree. (Pet. 8, at 1). Not until July 9th does

Evans report that he first introduced himself to McCleskey,

claiming that he was Ben Wright's uncle "Charles." (Pet. 8, at 3) .

24

5. Offie Evans

During the July 8-9, 1987, hearing, counsel for Mr.

McCleskey submitted both an oral report and affidavits to the

Court (RlSupp.-35- Aff't of Bryan A. Stevenson and Aff't of T.

Delaney Bell, both dated July 7, 1987), detailing their efforts

to locate Offie Evans — who had been recently released from

state prison, who was on probation to the Fulton County

Probation Office, who had been seen by two family members, but

who had declined to make himself available to Mr. McCleskey or

his counsel. Evans did not appear, and thus he did not testify.

(R4- 17-21).

D. The August 10, 1987 Federal Hearing

At the close of the July 8-9, 1987 federal hearing, the

District Court allowed Warden Zant a month's recess in order to

locate any further witnesses he might wish to call to rebut Mr.

McCleskey's evidence. (R5- 163-166).

1. The Testimony Of Ulysses Worthy

At the adjourned hearing on August 10th, Warden Zant re

called Ulysses Worthy. Mr. Worthy's August testimony accorded in

most fundamental respects with his July 9th account.13 Worthy

agreed, after some initial confusing testimony concerning Carter

Hamilton (a deputy jailor), that "an officer on the case ... made

13 On cross-examination, Mr. Worthy expressly reconfirmed

every important feature of his July 9, 1987 testimony, point-by

point. (R6- 25-35).

25

[a] request for [Evans] to be moved," (R6-50).14 In response to

questioning from the District Court, Worthy specifically

confirmed the following facts about the role of the Atlanta

police officers:

THE COURT: But you're satisfied that those three

things happened, that they asked to

have him put next to McCleskey, that

they asked him to overhear McCleskey, and

that they asked him to question McCleskey.

THE WITNESS: I was asked can — to be placed

near McCleskey's cell, I was asked.

THE COURT: And you're satisfied that Evans was

asked to overhear McCleskey talk about

this case?

THE WITNESS: Yes, sir.

THE COURT: And that he was asked to kind of try

to draw him out a little bit about it?

THE WITNESS: Get some information from him.

(R6- 64-65; accord. R6- 26-28).

It is only on two related points — exactly when Evans' move

was requested, and the number of (and participants in) various

meetings — that Worthy's August 10th testimony varies from his

July 9th testimony. Worthy's most noteworthy change was his

suggestion that the police request to move Evans did not come

until the close of the July 12, 1978, meeting between Evans,

Russell Parker, and Atlanta police officers. (R6- 16-19; id. 36-

38) . Worthy attempted on August 10th to explain that his

14 Worthy specifically testified that he did not consider

the jailor, Fulton County Deputy Sheriff Carter Hamilton, to have

been "an officer on the case." (R6-49, 65).

26

earlier testimony on this point had been misunderstood, and that

his first and only meeting with investigators had been the July

12, 1978, meeting attended by Russell Parker. (R6- 15-17; id.

36-37).

Yet on cross-examination, Worthy acknowledged that his

earlier, July 9th testimony made distinct references to (i) an

initial meeting, attended by Detective Dorsey, Offie Evans, and

Worthy (R5- 148), and (ii) a "subsequent meeting" with Mr. Evans

which occurred on a "later occasion" when "those detectives ...

came back out." (R5-151) . In his July 9th testimony, Worthy

testified that it was only at this "later" meeting that Russell

Parker was present. (Id.). Indeed, Worthy had not been able to

recall on July 9th whether Detective Dorsey had attended this

second meeting, although Worthy testified unequivocally that

Dorsey had been present at the first meeting. (Id.).

Moreover, Mr. Worthy was unable on cross-examination to

explain how Offie Evans could have; (i) overheard conversations

between McCleskey and Dupree on July 8-11, 1978; (ii) engaged in

extensive conversations with McCleskey on July 9-10, 1978; and

(iii) received a written note from McCleskey (which he passed

directly to Russell Parker during their July 12, 1978 meeting),

if Evans had been moved to a nearby cell only after July 12th.

(R6 -40-44). Nor could Worthy explain why Atlanta investigators

would have sought on July 12, 1978, to move Offie Evans to a

cell next to Warren McCleskey if Evans had already been in that

cell for at least four days prior to July 12th, gathering the

27

very fruits offered by Evans on July 12th. (R6- 39-44).

Mr. Worthy acknowledged that, at the time of the initial

federal hearing on July 9, 1987, he did not know the lawyers for

the parties, and that he knew nothing about the legal issues in

the McCleskey case or what other witnesses had said in their

testimony. (R6- 52-53). Between his first and his second court

appearances, however, Mr. Worthy had read a newspaper article

about the first hearing (R6- 55-56) and had met twice with

counsel for Warden Zant to discuss his earlier testimony. (R6-

53-54).

2. The Testimony Of Deputy Jailor Hamilton

At the August 10th hearing, in addition to re-calling

Ulysses Worthy, Warden Zant also re-called the Atlanta prosecutor

and police, who reiterated their denials of involvement with

Of fie Evans as an informant. Zant also called Carter Hamilton,

who had been a floor deputy at the Fulton County Jail in 1978.

(R4-176). Hamilton testified that he did not recall anyone

coming to the jail to speak with Offie Evans about the Schlatt

case until July 12, 1978, when he sat in on the meeting among

Evans, prosecutor Parker, and Atlanta police officers. (R6-68).

Deputy Hamilton testified that he had no knowledge of Evans

ever being moved while in jail. (R6-68). Although Hamilton was

present throughout the July 12, 1978 meeting between Evans,

Russell Parker and the Atlanta police officers, he heard no

requests during that meeting for Evans to be moved, or for Evans

to engage in conversations with Mr. McCleskey. (R6- 69-72).

28

/

On cross-examination, Deputy Hamilton admitted that he could

not say affirmatively whether Evans might have been held in

another part of the Fulton County Jail prior to July 8, 1978.

There were some 700 to 900 prisoners being held in July of 1978;

they were held on two separate floors in three different wings.

(R6-73) . Had Of fie Evans been held on the second floor or in a

different part of the Fulton County Jail between his initial

incarceration on July 3, 1978 and July 8, 1978, — or if a

movement had occurred during a different shift than the one

Deputy Hamilton worked — he admitted that he would have had no

knowledge of it. (R6- 72-76). Hamilton also acknowledged that he

had no specific memory of when Offie Evans first was placed in

the first-floor cell next to Mr. McCleskey. (R6-75).

E. The Findings Of The District Court

The District Court, after summarizing the testimony and the

documentary evidence (R3-22- 15-18, 19-21) and analyzing the

discrepancies in Worthy's testimony (R3-22- 16-18), found the

following:

After carefully considering the substance of Worthy's

testimony, his demeanor, and the other relevant

evidence in this case, the court concludes that it

cannot reject Worth's testimony about the fact of a

request to move Offie Evans. The fact that someone, at

some point, requested his permission to move Evans is

the one fact from which Worthy never wavered in his two

days of direct and cross-examination. The State has

introduced no affirmative evidence that Worthy is

either lying or mistaken. The lack of corroboration by

other witnesses is not surprising; the other witnesses,

like Assistant District Attorney Parker, had no reason

to know of a request to move Evans or, like Detective

Dorsey, had an obvious interest in concealing any such

arrangement. Worthy, by contrast, had no apparent

29

interest or bias that would explain any conscious

deception. Worthy's testimony that he was asked to

move Evans is further bolstered by Evans' [state

habeas corpus] testimony that he talked to Detective

Dorsey before he talked to Assistant District Attorney

Parker and by Evans' apparent knowledge of details of

the robbery and homicide known only to the police and

the perpetrators.

* * * *

[T]he court concludes that petitioner has established

by a preponderance of the evidence the following

sequence of events: Evans was not originally in the

cell adjoining McCleskey's; prior to July 9, 1978, he

was moved, pursuant to a request approved by Worthy, to

the adjoining cell for the purpose of gathering

incriminating information; Evans was probably coached

in how to approach McCleskey and given critical facts

unknown to the general public; Evans engaged McCleskey

in conversation and eavesdropped on McCleskey's

conversations with DuPree [McCleskey's co-defendant];

and Evans reported what he had heard between July 9 and

July 12, 1978 to Assistant District Attorney Parker on

July 12.

(R3-22- 21-22, 23; accord. RlSupp.-40- 9-10). In a subsequent

paragraph, the District Court summarized the likely motivation

for the scheme:

Unfortunately, one or more of those investigating

Officer Schlatt's murder stepped out of line.

Determined to avenge his death the investigator(s)

violated clearly-established case law, however

artificial or ill-conceived it might have appeared. In

so doing, the investigator(s) ignored the rule of law

that Officer Schlatt gave his life in protecting and

thereby tainted the prosecution of his killer.

(R3-22-31).

Ill. The Harmless Error Issue

Mr. McCleskey was tried by the Fulton County Superior Court

on one count of murder, and two counts of armed robbery. (Tr. T.

987). As indicated above, the State's evidence that McCleskey

30

was the actual perpetrator of the Schlatt homicide was limited to

some conflicting evidence on who was carrying the murder weapon,

the allegations of McCleskey's co-defendant Ben Wright, and the

testimony of Offie Evans. (See pages 14-16 supra).

At the close of the guilt phase, the Superior Court

instructed the jury on theories of malice murder (Tr. T. 998-999)

and of felony murder. (Tr. T. 999-1000). In its charge on malice

murder, the trial court instructed the jury that "a person

commits murder when he unlawfully and with malice aforethought,

either express or implied, causes the death of another human

being." (Tr. T. 1000). In its charge on felony murder, the trial

court informed the jury that "[t]he homicide is committed in the

perpetration of a felony when it is committed by the accused

while he is engaged in the performance of an act required for the

full execution of such a felony." (Tr. T. 1000) (emphasis added),

and that the jury should convict "if you believe and find beyond

a reasonable doubt that the homicide alleged in this indictment

was caused by the defendant while he, the said accused, was in

the commission of an armed robbery . . . ." (Id.).15

15 The court had earlier charged the jury, in a general

section, on the doctrine of "parties to a crime," as follows:

That statute says that every person concerned in the

commission of a crime is a party thereto and may be

charged with and convicted of commission of the crime,

and then it has several subsections. It says that a

person is concerned in the commission of a crime only

if he directly commits the crime, intentionally aides

or abets in the commission of the crime, or

intentionally advises, encourages, hires, counsels or

procures another to commit the crime.

31

During its deliberations, the jury sought further

instructions on the issue of malice murder. The Superior Court

repeated its instructions. (Tr. T. 1007-1009). Ten minutes

later, the jury returned, finding Mr. McCleskey guilty of malice

murder and two counts of armed robbery. (Tr. T. 1010).

During federal habeas proceedings, after determining that

Offie Evans' testimony was the product of unconstitutional

Massiah violations, the District Court addressed the possible

harmlessness of the violation. The court concluded that Offie

Evans' "testimony about petitioner's incriminating statements was

critical to the state's case" (R3-22-30):

There were no witnesses to the shooting and the murder

weapon was never found. The bulk of the state's case

against the petitioner was three pronged: (1) evidence

that petitioner carried a particular gun on the day of

the robbery that most likely fired the fatal bullets;

(2) testimony by co-defendant Ben Wright that

petitioner pulled the trigger; and (3) Evans' testimony

about petitioner's incriminating statements. As

petitioner points out, the evidence on petitioner's

possession of the gun in question was conflicting and

the testimony of Ben Wright was obviously impeachable.

. . .[T]he chronological placement of Evans testimony

[as rebuttal evidence] does not dilute its impact—

"merely" impeaching the statement "I didn't do it" with

the testimony "He told me he did do it" is the

functional equivalent of case in chief evidence of

guilt. . . . Because the court cannot say, beyond a

reasonable doubt, that the jury would have convicted

petitioner without Evans' testimony about petitioner's

incriminating statements, petitioner's conviction for

the murder of Officer Schlatt must be reversed pending

a new trial.

(R3-22- 29-31).

(Tr. T. 994).

32

IV. Warden Zant's Rule 60(b) Motion

In April of 1988, while this case was pending on appeal,

Warden Zant moved this Court to remand the case to the District

Court or to supplement the record, based upon the availability of

Of fie Evans, who had then been recently re-jailed on further

charges. After responsive papers were filed, the Court, on May

2, 1988, granted leave for Warden Zant to file a motion to reopen

the judgment in the District Court, pursuant to Rule 60(b).

Warden Zant filed such a motion on May 6, 1988. (RISupp.-

31). After receiving responsive papers (RISupp.-32), the

District Court found that Warden Zant had "fail[ed] to satisfy

the requirements for the relief sought. There is neither a

showing of due diligence nor a showing as to what Offie Evans

would say.” (RISupp.-34-1). Instead of dismissing the motion,

however, the District Court granted Warden Zant six weeks to

conduct additional discovery. (RISupp.-34-2).

A. The Issue Of Warden Zant's "Due Diligence”

During that discovery period, Warden Zant acknowledged, in

responses to written interrogatories: (i) that neither he nor

anyone under his direction ever sought to locate Offie Evans at

any point during or after the 1987 federal hearings (RISupp.-35-

Resp. Answer To First Interrog.-1-2) ; (ii) that he never

indicated, either to the District Court or to counsel for Mr.

McCleskey, his desire to call Offie Evans as a witness in 1987

33

(id. at 2)?16 and (iii) that he never attempted to follow up the

direct leads to Evans' whereabouts that had been revealed by Mr.

McCleskey's counsel during the initial July 8-9, 1987 hearing.

(Id.).17

Counsel for Mr. McCleskey also discovered, and presented the

District Court, documentary evidence that Offie Evans's

deposition had been taken in another case in October of 1981,

that the deposition had addressed the issue of Evans's contacts

with Atlanta police while in jail in 1978, and that Warden Zant's

present counsel had been aware of that deposition — indeed, had

offered it in another federal habeas case in 1985 — and had

obviously chosen not to offer it during Mr. McCleskey's 1987

16 The District Court specifically instructed Warden Zant,

during the one-month interval between the initial July, 1987

federal hearing and the August 10, 1987 rebuttal hearing, to

provide formal notice to Mr. McCleskey of any witnesses Zant

might call during the August 10th hearing. (R5-168). In neither

of two letters, dated July 24 and July 29, 1987, did counsel for

Warden Zant express any desire to call Offie Evans, nor did he

seek additional time or assistance to locate Evans.

17 During that hearing, counsel for Mr. McCleskey detailed,

in affidavits proffered to Warden Zant's counsel, the efforts

they had made to locate Offie Evans in May and June of 1987, just

prior to the hearing. (See R4-17; RlSupp.-35, Aff'ts of Bryon A.

Stevenson and T. Delaney Bell). Those affidavits reveal that, at

various times during May and June of 1987, Mr. Stevenson and/or

Mr. Bell had spoken with Offie Evans's sisters, who reported that

Evans was in and out of the two homes every few days.

Assistant District Attorney Parker was questioned under

oath, during the July 8th hearing, about Offie Evans's whereabouts. He responded:

"I understand he's just gotten out of jail, You Honor, but I do

not know where he is. I assume he's in the Atlanta area

somewhere. . . I could probably find him. I have spent enough

time with him." (R4-174) (emphasis added).

34

proceedings. (RISupp.-38-2, 18-19).

B. The Materiality Of Offie Evans's Testimony

During the discovery period, on July 13, 1988, Warden Zant

took the deposition of Offie Evans. That deposition was

thereafter submitted to the District Court in support of Warden

Zant's Rule 60(b) motion. (RISupp.-37).18 During his deposition,

Evans denied ever having been moved while in the Fulton County

Jail in 1978, or ever having been asked to serve as an informant

against Warren McCleskey. (RISupp.-37- 15-21).

Evans' deposition testimony contained a number of internal

contradictions, as well as contradictions with his own former

testimony and the testimony of other officers. For example,

Evans testified that he began speaking with McCleskey on July 3,

1978, the first day he was incarcerated, while the two were in

adjacent cells. (RISupp.-37-15, 54). In 21-page typewritten

statement to Russell Parker, however, Evans states that he did

not begin speaking with McCleskey until five days after his

incarceration, on July 9th. (Fed. Exh. 8). During his July 13th

deposition, Evans denied ever meeting with Russell Parker prior

to August 1, 1987 (RISupp.-37-21); Parker and other witnesses

testified that the two met on July 12, 1978.

Evans also maintained during his 1988 deposition that

Detective Dorsey had never promised to "speak a word for him" in

18 Although the court subsequently contacted counsel for

both parties, inquiring whether either sought an evidentiary

hearing on the Rule 60(b) motion, Warden Zant did not request an

opportunity to present Evans' live testimony.

35

exchange for his testimony against Mr. McCleskey (RISupp.-37-92).

His sworn testimony in state habeas corpus proceedings in 1981

was directly to the contrary. Evans denied that he had ever

served as an informant prior to 1978, and specifically denied any

prior acquaintance with Detective Dorsey. (RISupp.-37-46, 75).

This testimony contradicted Dorsey's testimony during the 1987

federal hearings, as well as the information about Evans's

informant activities which Russell Parker obtained from the FBI

and from Federal Corrections officials. Evans also denied that

he had spoken with Russell Parker in 1988 prior to his

deposition. (RISupp.-37-33) . Warden Zant's 1988 Answers to

Interrogatories revealed that Offie Evans had participated in a

telephone conversation with Russell Parker after his re

incarceration in the spring of 1988. (RISupp.-35-Resp. Answer to

First Interrog. at 3).19

C. The Findings Of The District Court

In its order denying Rule 60(b) relief, the District Court

found that "Evans' testimony is not truly newly discovered but

rather is merely newly produced. . . The fact that the essential

substance of this testimony was in a previous deposition filed in

the public records and known to respondent's counsel also

indicates it is not newly discovered." (RISupp.-40-6).

Turning to the issue of due diligence, the District Court

19 A review of 19 inconsistencies and contradictions in

Offie Evans's deposition is set forth at pages 8 through 17 of

Petitioner's Brief In Response To Respondent's Supplement To Rule

60(b) Motion. (RISupp.-38).

36

found that "respondent made no efforts to locate Evans during the

summer of 1987." (RISupp.-40-8). "[T]he Atlanta Bureau of Police

Services has enjoyed a special relationship with Mr. Evans over

the years, and . . . if the department had been looking for him,

Mr. Evans might have made himself available" to Warden Zant.

(Id.-7). The court concluded that "petitioner's efforts did not

relieve respondent of any obligation to utilize his own resources

to locate Evans. Movant has not demonstrated the due diligence

prong of the 60(b)(2) standard." (Id.).

Finally, addressing the impact of Evans's testimony, the

District Court found that

[i]t is unlikely Evans' testimony would produce a

different result. The credibility or believability

problems with his testimony are evident. He has a

strong motivation for saying he was not an informant,

not only because of recriminations from his

associates, but also in order to stay in favor with the

police and prosecutors who have used him to testify in

the past. The numerous contradictions within his

deposition also lead the court to the conclusion that

his testimony would not be believable.

(Id. at 9). The court closed its analysis by noting that it had

already credited the word of Ulysses Worthy against the sworn

testimony of Atlanta law enforcement personnel: "Evans testimony

is not likely to change the credibility of Worthy's testimony or

the fact that petitioner showed by a preponderance of the

evidence that a Massiah violation occurred. (Id. at 10).

(iii) Statement of the Standard of Review

Mr. McCleskey agrees with Warden Zant that the appropriate

standard to be applied to the Rule 9(b) issue and the Rule 60(b)

37

issue on this appeal is whether the District Court abused its

discretion. Mr. McCleskey's constitutional claim under Massiah

v. United States presents mixed questions of fact and law. The

ultimate legal questions presented by that claim should be

independently reviewed by this Court.

Under Rule 52 of the Fed. R. Civ. P. , the District Court's

factual findings on all issues — Zant's Rule 9(b) allegations,

the merits of the Massiah claim, harmless error, and Rule 60(b)

— should not be disturbed unless they are clearly erroneous.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The gravamen of Warden Zant's appeal is that this Court

should overturn virtually every major fact found by the District

Court. Zant's appeal should be denied, since the District

Court's factual findings are not "clearly erroneous."

The governing standard, Rule 52 of the Fed. R. Civ. P. does

not permit this Court independently to reweigh the extensive

factual record. "'Where there are two permissible views of the

evidence, the factfinder's choice between them cannot be clearly

erroneous.'" Amadeo v. Zant. U.S. , 100 L.Ed.2d 249, 262

(1988), citing Anderson v. Bessemer City. 470 U.S. 564, 574

(1984). Only if Zant could demonstrate that only one view of the

evidence exists would his appeal have merit.

Zant's burden is insurmountable on this record. The

District Court heard extensive live testimony and carefully

sifted hundreds of pages of documentary evidence before reaching

its decision. The lower court's judgment, embodied in two

38

thorough opinions, expressly considers the alternative views of

the evidence and clarifies, with great care, the court's choices

among them.

The Massiah claim plainly turns on the District Court's

credibility assessment of three key witnesses, two of whom

testified before the court — jailor Ulysses Worthy and Detective

Sidney Dorsey — and one of whom — Of fie Evans — appeared via

two hearing transcripts and an 100-page deposition. The Supreme

Court has stressed that "[w]hen findings are based on

determinations regarding the credibility of witnesses, Rule 52(a)

demands even greater deference to the trial court's findings; for

only the trial judge can be aware of the variations in demeanor

and tone of voice that bear so heavily on the listener's

understanding of and belief in what is said." Anderson v. City

of Bessemer City. 470 U.S. 574, 575 (1985).

The District Court's factual determinations are not only

defensible; they are by far the most plausible reading of the

evidence. The various threads of Offie Evans's testimony — his

admission during state habeas proceedings about a jailhouse

meeting with Detective Dorsey, his remarkably unguarded 21-page

statement to Atlanta law enforcement personnel (during which he

brags repeatedly about the extensive web of lies by which he

gradually won Warren McCleskey's confidence) — were tied tightly

together by Ulysses Worthy's unrehearsed account of the jailhouse

meeting at which Atlanta police officers recruited Offie Evans to

serve as an active informant. This testimony meshes into a

39

coherent fabric of deceit and constitutional misconduct,

concealed for nearly a decade.

The District Court*s basic conclusions thus find consistent

support in the record; they are fully supported and not "clearly

erroneous."

Warden Zant's additional contentions also founder on the

District Court's factfindings. Although Zant argues that Mr.

McCleskey "deliberately abandoned" his Massiah claim, the

District Court found that the essential facts had been concealed

from McCleskey during his initial state habeas proceedings. The

court properly held that an applicant may not be held

"deliberately" to have abandoned a constitutional claim when the

supporting facts were not reasonably available to him. See e.q..

Potts v. Zant. 638 F. 2d 727, 741-743 (5th Cir. Unit B 1981);

accord: Price v. Johnston. 334 U.S. 266 (1948).

Zant also argues that Mr. McCleskey should have discovered

the evidence hidden by State authorities. Zant's position

ignores basic equitable principles: a court should not permit a

party seeking equity to take advantage of his own misconduct.

Sanders v. United States. 373 U.S. 1, 17-18 (1963). The State