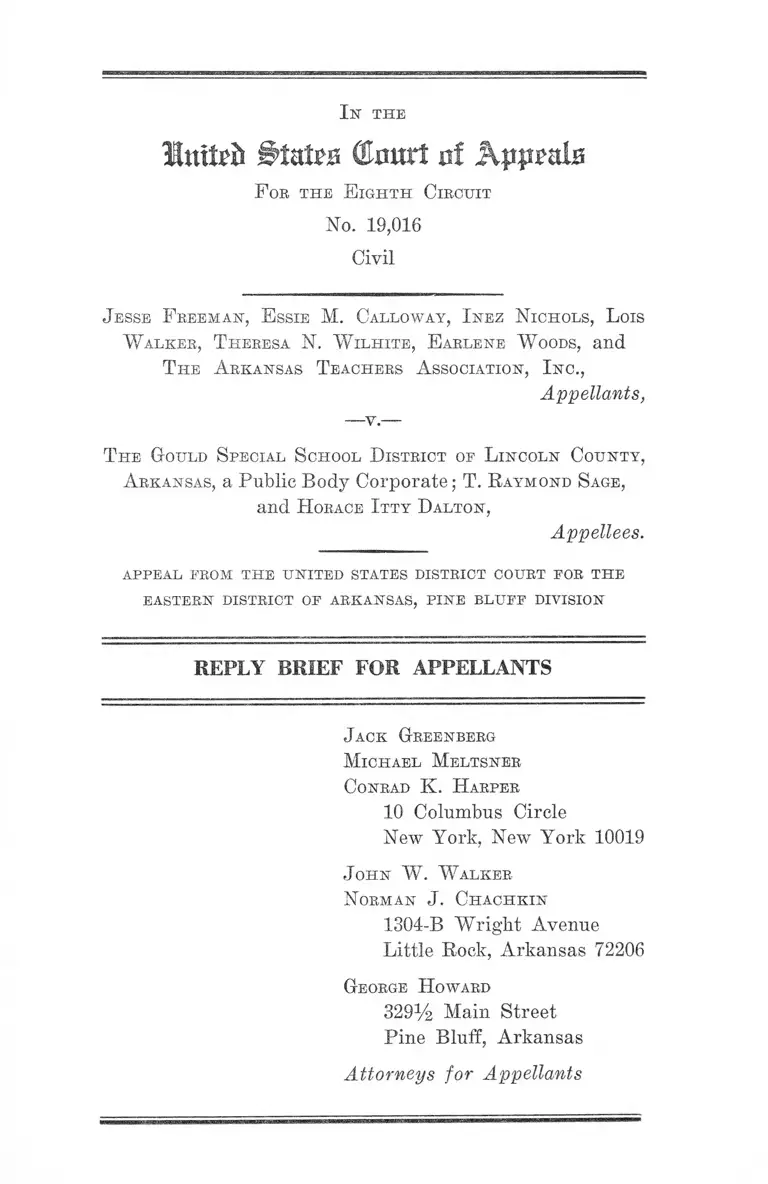

Freeman v. Gould Special School District Reply Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Freeman v. Gould Special School District Reply Brief for Appellants, 1969. 6b704872-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/531dd237-13e0-4706-95c6-8bc9d3c5e005/freeman-v-gould-special-school-district-reply-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

luttrii Court of KppmIs

F or t h e E ig h t h C ir c u it

No. 19,016

Civil

J esse F r e e m a n , E ssie M. Callow ay , I n e z N ic h o l s , L ois

W a lk er , T h er esa N . W il h it e , E a rlen e W oods, a n d

T h e A rk a n sa s T ea c h er s A ssociation , I n c .,

Appellants,

— v .—

T h e G ould S pe c ia l S chool D ist r ic t op L in c o l n C o u n t y ,

A rk a n sa s , a Public Body Corporate; T. R aymond S age,

a n d H orace I tty D a lto n ,

Appellees.

a p p e a l f r o m t h e u n i t e d s t a t e s d i s t r i c t c o u r t f o r t h e

E A ST E R N D IS T R IC T OF A R K A N SA S, P IN E B L U F F D IV ISIO N

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

J ack Green berg

M ic h a e l M e l t sn e r

C onrad K. H arper

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J o h n W . W a lk er

N orm an J . C h a c h k in

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas 72206

G eorge H oward

329% Main Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of Point to Be Argued ............................... 1

A r g u m e n t—

Appellants’ Rights to Due Process of Law Were

Violated by the Procedures of the Gould Special

School District in Not Reemploying Them ........ . 2

C o n c lu sio n ............................................................................... ........... 8

T able of Ca s e s :

Alpert v. Bd. of Governors of City Hospital of Fulton,

286 App. Div. 542, 145 N.T.S. 2d 534 (1955) ........ . 2,5

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) .... 2, 6, 7

Hanifan v. United States, 354 F.2d 358 (Ct. Cl. 1965) ..1, 3, 4

Johnson v. City of Ripon, 259 Wis. 84, 47 N.W. 2d 328

(1951) .......... ................................................. ..... ........ 1,5

Johnson v. Wert, 225 Ark. 91, 275 S.W. 2d 274 (1955) .. 2, 7

Morgan v. United States, 304 U.S. 1 (1937) .......... 2, 3, 5, 7

Osborne v. Bullitt County Board of Education, 415

S.W. 2d 607 (Ky. 1967) .................................. .......2,6,7

Raney v. Board of Education, 381. F.2d 252 (8th Cir.

1967), cert, granted, 389 U.S. 1034 (No. 805, 1967

Term) ............... ..................... ....................... .......... . 2, 7

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 (1960) ...... ................ 2,6

State ex rel. Steele v. Board of Education of Fairfield,

252 Ala. 254, 40 So. 2d 689 (1949) ........................ 2, 3, 5

11

S t a t u t e :

PAGE

Ark. Stat. Ann. § 80-1304 .................-.......................... 7

O t h e r A u t h o r it y :

Developments in the Law—Academic Freedom, 81

TIarv. L. Rev. 1045 (1968) ...............-....................... 7

I n t h e

Imtpft Btntm (Hamt uf Appeals

F oe t h e E ig h t h C ir c u it

No. 19,016

Civil

J esse F r e e m a n , E ssie M. C allow ay , I n e z N ic h o l s , L ois

W a l k e r , T h eresa N. W il h it e , E a rlen e W oods, a n d

T h e A rk a n sa s T ea c h er s A ssociation , I n c .,

Appellants,

— v.—

T h e G ould S pe c ia l S chool D ist r ic t of L in c o l n C o u n t y ,

A rk a n sa s , a Public Body Corporate; T. R a y m o n d S age,

and H orace I tty D a lto n ,

Appellees.

A P P E A L FRO M T H E U N IT E D STA TES D IST R IC T COU RT FO R T H E

E A ST E R N D IST R IC T OP A R K A N SA S, P IN E B L U F F D IV ISIO N

REPLY BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF POINT TO BE ARGUED

Appellants’ Rights to Due Process of Law Were Vio

lated by the Procedures of the Gould Special School

District in Not Reemploying Them.

Hanifan v. United States, 354 F.2d 358 (Ct, Cl.

1965);

Johnson v. City of Ripon, 259 Wis. 84, 47 N.W.

2d 328 (1951);

2

Morgan v. United States, 304 U.S. 1 (1937);

Osborne v. Bullitt County Board of Education,

415 S.W. 2d 607 (Ky. 1967);

Alpert v. Board of Governors of City Hospital

of Fulton, 286 App. Div. 542, 145 N.Y.S. 2d

534 (1955);

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 IJ.8. 483

(1954) ;

Johnson v. Wert, 225 Ark. 91, 275 S.W. 2d 274

(1955) ;

Raney v. Board of Education, 381 F.2d 352 (8th

Cir. 1967) cert, granted 389 1T.S. 1034 (No.

805, 1967 Term) ;

Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 379 (1960);

State ex rel. Steele v. Board of Education of

Fairfield, 252 Ala. 254, 40 So. 2d 689 (1949).

ARGUMENT

Appellants’ Rights to Due Process of Law Were Vio

lated by the Procedures of the Gould Special School

District in Not Reemploying Them.

In attempting to sustain the actions of the school board

in not rehiring appellant teachers, appellees make two prin

cipal arguments: (a) appellees claim that unless appellants

were engaged in protected constitutional activities, appel

lants were not entitled at the time of their discharge to due

process of law under the Fourteenth Amendment (Appel

lees’ Brief, pp. 15-21) ; and (b) assuming arguendo appel

lants’ rights to procedural due process, that such rights

were not violated (Appellees’ Brief, pp. 22-25). The fol

lowing reply brief is a short rejoinder to these arguments.1

1 Appellees have presented a statement of facts somewhat dif

ferent from that contained in appellants’ brief at pp. 4-21, 27-30, 32.

3

We submit appellees have totally misconceived the nature

of procedural due process and failed to recognize that the

Constitution forbids arbitrary or capricious governmental

action in removing teachers from their positions. Princi

ples forbidding arbitrary action by public bodies are well

illustrated by Morgan v. United States, 304 U.S. 1 (1937),

where an order of the Secretary of Agriculture fixing maxi

mum rates chargeable by stockyard markets was set aside.

The Morgan court reasoned that procedures provided by

the Secretary for challenging administrative orders were

insufficient under the Due Process Clause. The court held

that: “The right to a hearing embraces not only the right

to present evidence but also a reasonable opportunity to

know the claims of the opposing party and to meet them.”

304 U.S. at 18. See also State ex rel. Steele v. Board of

Education of Fairfield, 252 Ala. 254, 40 So. 2d 689 (1949),

where due process principles were applied to the discharge

of a tenured teacher.

It is undisputed that Principal Dalton, appellants’ chief

accuser, was not present at either of the board hearings

granted after appellants were not rehired (R. 85, 223, 250).

Dalton also testified that he did not give any of appellants

advance notice of his adverse recommendations (R. 111).

Notwithstanding these facts, appellees seek to defend the

Board’s actions by stating that “Dalton had mentioned his

complaints to appellants at faculty meetings prior to his

recommendation and the Board’s action (R. 39)” (Brief for

Appellees, p. 23). A reading of the record at page 39, cited

by appellees, shows, however, that the essence of Dalton’s

vague testimony is this: “when I call my faculty meetings,

I just didn’t specify the person, see. I talked to the whole

group” (R. 39).

Appellants do not propose to reargue the facts at length but we do

urge the Court to examine the entire record in resolving factual

issues.

4

Appellees further assert, dehors the record, “Appellants

never requested an opportunity to confront and cross-

examine Principal Dalton at a hearing” (Brief for Appel

lees, p. 23). This is not true. At the second hoard hearing,

appellants’ counsel, Mr. Walker, specifically requested that

Mr. Dalton he present but this request was denied. Present

at the second board hearing when this request was made

were, among others, Robert V. Light, counsel for appellees;

members of the school board; appellants; and George

Howard, counsel for appellants. Appellees’ failure to pro

duce Dalton at any board hearing is analogous to the illegal

failure of the Civil Service Commission under its regula

tions to produce the chief accusers of a discharged civil

servant at a Commission hearing. Hanifan v. United States,

354 F. 2d 358 (Ct. Cl. 1965).

Appellees also seek to defend the absence of Dalton at

the board hearings by noting Dalton’s deposition was taken

by appellants between the first and second hearings. (Brief

for Appellees, p. 23). This view, however, ignores the

crucial fact that the charges against appellants were differ

ent at each board hearing and at trial (R. 219-220, 222, 233-

235). Thus in no real sense could the deposition of Dalton

be held to have given appellants adequate notice of all

reasons for the board’s continued refusal to rehire them.

Appellees seek to sweep this problem under the rug by

admitting “appellants were questioned about different inci

dents at varying stages of the proceedings” but denying

that such questioning constituted different sets of charges

(Brief for Appellees, p. 23). In view of the fact that appel

lees’ case, such as it is, consists largely of alleged instances

of appellants’ misconduct (see Brief for Appellants, pp.

11-21, p. 32 n. 8), we are unable to perceive any rational

basis upon which to subscribe to appellees’ distinction be

tween “charges” and “incidents”. Appellees’ distinction

5

does, however, demonstrate the true nature of the board’s

actions: Having dismissed appellants without prior notice

to them, the board was acting in the words of State ex rel.

Steele v. Board of Education of Fairfield, supra, 252 Ala.

at 261, 40 So. 2d at 695, as “complainant, prosecutor and

judge” in seeking any basis upon which to ratify its earlier

decision not to reemploy appellants, or, as appellees put

it, these “were newly discovered incidents which the Board

deemed probative of the truth of the principal’s charges of

incompetency and non-cooperation” (Brief for Appellees,

P- 23)

Appellees suggest, moreover, that discharge of a non-

tenured teacher who engaged in no constitutionally pro

tected activity, is affected by no due process requirements

(Brief for Appellees, p. 12, 19). It must not be forgotten

in this context, however, that appellants’ contracts were

terminated without notice or a hearing (R. 218, 222, 224).

Courts have found, in the analogous situation of a public

hospital’s removal of qualified physicians from its medical

staff without notice or a hearing, that such procedures vio

late due procss. Johnson v. City of Ripon, 259 Wis. 84, 47

N.W. 2d 328 (1951); Alpert v. Bd. of Governors of City

Hospital of Fulton, 286 App. Div. 542, 145 N.Y.S. 2d 534

(1955).

Appellees assert that the charges against appellants are

sufficient to sustain the board’s actions (Brief for Appel

lees, p. 21, and n. 3). This assertion overlooks the require

ments of due process, particularly the requirement of

specificity of alleged misbehavior. Putting aside for the

moment the issue that appellants met different charges at

each stage of the proceedings, it is clear that none of the

charges against them was sufficiently specific.2 Remark

2 The charges are set out in Brief for Appellants, pp. 11-21, p. 32,

n. 8.

6

ably similar charges were made against a teacher in Osborne

v. Bullitt County Board of Education, 415 S.W. 2d 607

(Ky. 1967). The Osborne charges set out in the margin3

were held “to be too vague and indefinite to furnish the

appellant with sufficient information upon which he could

base a defense,” 415 S.W. 2d at 610. The court further

held, on the basis of a state statute and due process, that

dismissal of a teacher so charged, who also had a contract,

was invalid.

Given the disapproving words of the Supreme Court as

to the unconfined latitude permitted school authorities by

Arkansas law in not reemploying teachers, Shelton v.

Tucker, 364 U.S. 479, 485-86 (1960), the opportunity for

capricously not reemploying appellants was present and,

3 415 S.W. 2d at 608:

“1. Insubordination based upon fact that you refuse to co

operate with the principal of your school in the conduct of

the school and the orders issued by him and your conduct

toward him has been such that it is disruptive of the

progress of the school.

“2. You have distributed alleged copies of confidential records

from files of the school that have because of your so doing

has violated instruction of your superiors in office and

created prejudices against the manner in which the school

has been conducted (sic).

“3. You have failed to properly instruct the pupils in the sub

jects taught by you and do not have proper attention from

or control over your pupils.

“4. You have installed in your room, where you teach, a punch

ing bag, without necessary permission to do so and without

permission have moved basketball basket from where they

were located (sic) to other places.

“5. Your suggestion as to conduct of P.T.A. has been such as

would cause same to be discredited if followed out.

“6. Your conduct in connection with teaching has not been for

best interest of the school.

“7. In threatening to file suit against the principal of the

school and statements included in the copies of confidential

reports distributed by you (sic).”

as the facts of this case show, well used.4 An irony of the

instant case is that since Ark. Stat. Ann. § 80-1304 author

izes the non-reemployment of teachers for any reason or

without reason (Johnson v. Wert, 225 Ark. 91, 275 S.W. 2d

274 (1955)), appellees argue the board’s hearings—with all

their infirmities—exceeded the requirements of due process

(Brief for Appellees, pp. 22-25). If § 80-1304 had explicitly

authorized non-reemployment merely because a principal

personally disliked a teacher, there would be little difficulty

in successfully challenging the statute as unconstitutionally

broad, cf. Osborne v. Bullitt County Board of Education,

supra, 415 S.W. 2d at 610. But § 80-1304 authorizes entirety

arbitrary discharges and this record, showing Principal

Dalton’s incompetence and the school board’s utter reliance

upon him and upon different “reasons” for appellants’ dis

charges at every turn, demonstrates that appellees have not

hesitated to be, in fact, entirely arbitrary.

In the broadest sense this case presents the issue whether

the academic freedom of teachers to be unpopular with

their principal is safeguarded by due process of law. See

Developments in the Law—Academic Freedom, 81 Harv. L.

Rev. 1045, esp. 1077-84 (1968). Appellees suggest that ap

pellants as non-tenure teachers, received adequate, indeed

exceptional, due process (Brief for Appellees, pp. 22-25).

We submit, however, that our original brief and the fore

going argument demonstrate such a host of constitutional

infirmities that the district court’s judgment cannot stand.

4 Appellees make much of the fact that appellants purportedly

were discharged on non-racial grounds (Brief for Appellees, p. 18).

But the instant case has not arisen in a vacuum. Many years after

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), and only

shortly before appellants were not rehired, the school district con

tinued to operate all-white and all-Negro schools. Haney v. Board

of Education, 381 F.2d 252, 256 (8th Cir. 1967), cert, granted, 389

U.S. 1034 (No. 805, 1967 Term).

8

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, and the reasons contained in

the appellants’ original brief, appellants submit that the

judgment of the district court should be reversed or in the

alternative, that the district court’s judgment should be

vacated and the cause remanded for additional findings of

fact.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G reen berg

M ic h a e l M e l t sn e r

C onrad K. H arper

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

J o h n W . W a lk er

N orm an J . C h a c h k in

1304-B Wright Avenue

Little Rock, Arkansas 72206

G eorge H oward

329*4 Main Street

Pine Bluff, Arkansas

Attorneys for Appellants

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C .«^ p s»219