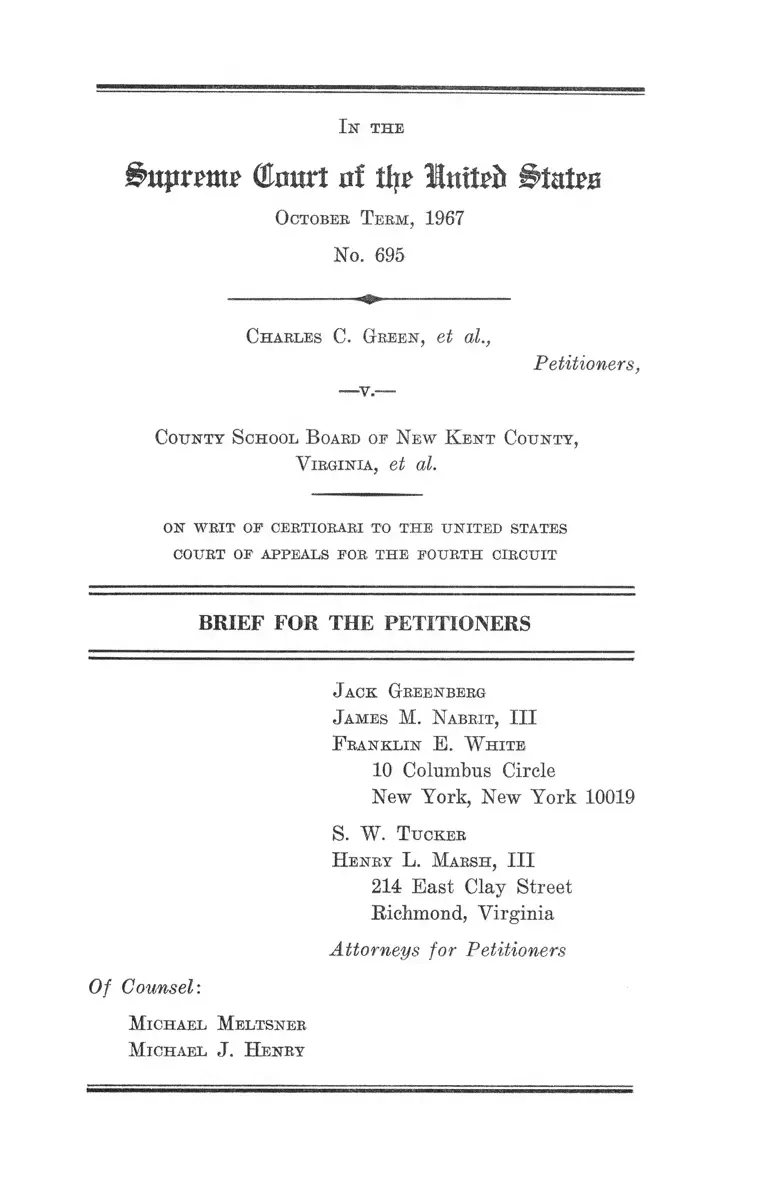

Green v. New Kent County, VA School Board Brief for the Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Green v. New Kent County, VA School Board Brief for the Petitioners, 1967. 8f941727-b49a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/538314d9-34d1-42bb-9707-1cd3a80bfea4/green-v-new-kent-county-va-school-board-brief-for-the-petitioners. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

I n t h e

B npnm x ( to r t of tfy? Imtrfr Stairs

O ctober T erm , 1967

No. 695

C harles C. Gr e e n , et al.,

Petitioners,

— v.—

C ounty S chool B oard of N ew K e n t C ounty ,

V irg in ia , et al.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE PETITIONERS

J ack Greenberg

J am es M. N abr.it , III

F r a n k l in E. W h it e

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

S. W. T u ck er

H en ry L. M a rsh , III

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia

Attorneys for Petitioners

Of Counsel:

M ic h a el M eltsn er

M ich a el J . H en ry

I N D E X

Citations to Opinions Below ........... 1

Jurisdiction ................................................................... 1

Question Presented ............................................... 2

Constitutional Provision Involved ............................... 2

Statement ....................................................................... 2

I. The Pleadings .................................................. 2

II. The Plan Adopted by the B oard..................... 4

III. The Evidence ... ...................... 5

IY. The District Court’s Decision.......................... 8

V. The Court of Appeals’ Opinion...................... 8

Summary of Argument...................... 11

A rg u m en t :

I. Introduction ...... ............................................... 13

II. A Freedom of Choice Plan Is Constitutionally

Unacceptable Where There Are Other Meth

ods, No More Difficult to Administer, Which

Would More Speedily Disestablish the Dual

System............................................................... 27

PAGE

11

PAGE

A. The Obligation of a School Board Under

Brown v. Board of Education Is to Dises

tablish the Dual School System and to

Achieve a Unitary, Non-raeial System ..... 28

1. The Fourth Circuit’s Adherence to

Briggs ..................................................... 28

2. Brown Contemplated Complete Reor

ganization ............................................... 30

3. Case and Statutory Law ..................... 32

4. Equitable Analogies ................. 38

5. Summary ............................................... 39

III. The Record Clearly Shows That a Freedom

of Choice Plan Was Not Likely to Disestab

lish, and Has Not Disestablished, the Dual

School System and That a Geographic Zone

Plan or Consolidation Would Immediately

Have Produced Substantial Desegregation .... 41

C o n c l u s io n .................. .......................... ........................................... 50

TABLE OF CASES

American Enka Corp. v. N. L. B. B., 119 F. 2d 60 (4th

Cir. 1941) ................................................................... 39

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U. S. 399 ............................... 42n

Board of Education of Oklahoma City Public Schools

v. Dowell, 372 F. 2d 158 (10th Cir. 1967) .............. 37

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 .................................... 30

I l l

Borders v. Rippy, 247 F. 2d 268, 271 (5th Cir., 1957) .. 28n

Boson v. Rippy, 285 F. 2d 43, 48 (5th Cir., 1960) ....... 28n

Bowman v. County School Board of Charles City

County, Va., 382 F. 2d 326 (4th Cir. 1967) .............. 9n

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, 382

U. S. 103 .......................................................... 18n, 27n, 30

Braxton v. Board of Public Instruction of Duval

County, Florida, No. 4598 (M. D. Fla.), January 24,

1967 ............................................................................ 49n

Briggs v. Elliot, 132 F. Supp. 776 (E. D. S. C. 1955) ..28, 33

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 IT. S. 483, 349 U. S.

294 .................................................4n, 13,15n, 21, 30, 31, 47

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U. S.

715 ......................... 42n

Calhoun v. Latimer, 377 U. S. 263 ............................ 30n

Carpenter v. Steel Co., 76 NLBB 670 (1948) .............. 39

Clark v. Board of Education, Little Rock School Dis

trict, 369 F. 2d 661 (8th Cir. 1966) ......................... 48n

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ....................................30, 31n

Coppedge v. Franklin County Board of Education,

273 F. Supp. 289 (E. D. N. C. 1967) ..................... 23n, 49n

Corbin v. County School Board of Loudon County,

Virginia, C. A. No. 2737, August 27, 1967 ............. 49n

Dove v. Parham, 282 F. 2d 256 (8th Cir. 1960) 15n

Evans v. Ennis, 281 F. 2d 385 (3rd Cir. 1960) .......... 37

Farley v. Turner, 281 F. 2d 131 (4th Cir.) ............... 16

Franklin v. County School Board of Giles County,

Va., 242 F. Supp. 371 (W. D. Va. 1965) reversed

360 F. 2d 325 (4th Cir. 1966) .................................... 17n

PAGE

IV

Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction of Dade County,

272 F. 2d 763 (5th Cir. 1959) .................................. 15n

Gilliam v. School Board of the City of Hopewell, Va.,

345 F. 2d 325 (4th Cir. 1965) remanded 382 U. S.

103 (1965) ................................................................. 17n

Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 683 ...... 30n, 42n, 43n

Green v. County School Board of the City of Roanoke,

304 F. 2d 118 (4th Cir. 1962) .................................... 17

Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, 377 TJ. S. 218 (1964) ................................ 27n, 30n

Hamm v. County School Board of Arlington County,

264 F. 2d 945 (4th Cir. 1960) ......... ........................ 16n

Harrison v. Day, 200 Va. 439, 106 S. E. 2d 636 .......... 16n

James v. Almond, 170 F. Supp. 331 (E. D. Va. 1959) .. 16n

Jeffers v. Whitley, 309 F. 2d 621 (4th Cir., 1962) ....... 28n

Kelley v. Altheimer Arkansas Public School District,

378 F. 2d 483 (8th Cir., 1967) ......................... .......36, 46n

Kelley v. Board of Education of the City of Nashville,

270 F. 2d 209 (6th Cir., 1959) .............................. 28n, 33n

Kemp v. Beasley, 352 F. 2d 14 (8th Cir. 1965) .......... 36

Kemp v. Beasley, — - F. 2d ----- , No. 19017 (8th

Cir. Jan. 9, 1968) ............................................. 37n, 43n, 44

Lane v. Wilson, 307 U. S. 268 ...................................... 46n

Louisiana v. United States, 380 IT. S. 145 ..................38, 47

Manning v. Board of Public Instruction of Hillsboro

County, 277 F. 2d 370 (5th Cir., 1960)

PAGE

15n

V

Marsh v. County School Board of Roanoke County,

Va., 305 F. 2d 94 (4th Cir., 1962) ............................. 17

Mason v. Jessamine County Board of Education, 8

Race Eel. L. Rep. 530 (E. D. Ky. 1963) .................. 49n

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of the City of

Jackson, Term., 380 F. 2d 955 (6th Cir. 1967) cert.

granted, No. 740 ( 0. T. 1967) ................................ 13, 33n

Moses v. Washington Parish School Board, ----- F.

Supp.----- (E. D. La. Oct. 19, 1967) ............ .14n, 19, 49n

N. A. A. C. P. v. Patty, 159 F. Supp. 503 ..................... 16n

N. L. R. B. v. Newport News Shipbuilding and Dry

Dock Co., 308 U. S. 241 ........................................... 39

Northcross v. Board of Education of the City of Mem

phis, 302 F. 2d 818 (6th Cir., 1962) ......................... 15n

Norwegian Nitrogen Products Co. y. United States,

288 U. S. 294 .............. ............................................... 32n

Pettaivay v. County School Board of Surry County,

Va., 230 F. Supp. 480 (E. D. Ya. 1964), modified

and remanded, 339 F. 2d 486 (4th Cir.) .................. 17n

Porter v. Warner Holding Co., 328 IT. S. 395 .......... 38

Raney v. The Board of Education of the Gould School

District, 381 F. 2d 252 (8th Cir. 1967), cert, granted,

No. 805 ..................................................................... 13, 36n

Reitman v. Midkey, 18 L. ed. 831 ................................ 42n

Robinson v. Florida, 378 U. S. 153 ............................. 42n

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U. S. 198 ....................... ........... 30n, 48n

Schine Chain Theatres v. United States, 334 U. S. 110 38

School Board of City of Charlottesville v. Allen, 263

F. 2d 295 (4th Cir. 1959)

PAGE

16n

v i

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 348 F. 2d 729 (5th Cir. 1965) .......................... 35n

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dis

trict, 355 F. 2d 865 (5th Cir. 1966) ..................... 18n, 35n

Skidmore v. Swift & Co., 323 U. S. 134 ..................... 32n

Sperry Gyroscope Co. Inc. v. NLRB, 129 F. 2d 922,

931-932 (2d Cir. 1942) ............................................... 39

Swann v. Charlotte Mecklenburg Board of Education,

369 F. 2d 29 (4th Cir. 1966) .................................... 30n

United States v. American Trucking Associations,

Inc., 310 U. S. 534 ...................................................... 32n

United States v. Crescent Amusement Co., 323 U. S.

173 .............................................................................. 38

United States v. County School Board of Prince

George County, Va., 221 F. Supp. 93, 105 (E. D.

Va. 1963) ..................................................................... 17n

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Educa

tion, 372 F. 2d 836, ail’d with modifications on re

hearing en banc, 380 F. 2d 385, cert, denied sub nom.

Caddo Parish School Board v. United States, 389

U. S. 840, 19 L. ed. 103 (1967) ..............4n, 9 ,18n, 33, 46n

United States v. Standard Oil Co., 221 U. S. 1 .......... 38

Vick v. Board of Education of Obion County, 205 F.

Supp. 436 (W. D. Tenn. 1962) ................................. 28n

PAGE

Watson v. Memphis, 373 U. S. 526 27n

VU

STATUTES

Code of Va., 1950 (1964 Replacement Vol.)

§22.232.1.....................................................................6 ,16n

§22.232.6 ................................................................. 6

§22.232.20 ................................................................ 6

45 C. F. R, Part 181 ........................................ .......... 22, 32n

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 241 .........................3, 32n

28 U. S. C. §1331 .................... 3n

28 U. S. C. §1343 ......................... 3n

42 U. S. C. §1981 .......................................................... 3n

42 U. S. C. §1983 .......................................................... 3n

42 U. S. C. §2000-c ...................................................... 32n

42 U. S. C. §2000-d ....... 32n

OTHER AUTHORITIES

PAGE

Black, The Supreme Court, 1966 Term—Foreword:

“State Action,” Equal Protection and California’s

Proposition 14, 81 Harv. L. Rev. 69 (1967) ........... . 42n

Campbell, Cunningham and McPhee, The Organisa

tion and Control of American Schools, 1965 ...... 13n, 14n

Conant, The American High School Today (1959) .... 44

Dunn, Title VI, The Guidelines and School Desegre

gation in the South, 53 Va. L. Rev. 42 (1967) ...... 30n, 32n

Equality of Educational Opportunity: A Report of

the Office of Education of the United States Depart

ment of Health, Education and W elfare................. 21n

Meador, The Constitution and the Assignment of

Pupils to Public Schools, 45 Ya. L. Rev. 517 (1959) 14

Mizell, The South Has Genuflected and Held on to

Tokenism, Southern Education Report, Vol. 3, No.

6 .................................................................................. 23n

Note, The Courts, HEW and Southern School Deseg

regation, 77 Yale L. J. 321 (1967) ......................... 32n

Racial Isolation in the Public Schools, Volume I:

A Report of the United States Commission on Civil

Rights 1967 ................................ 27n

Revised Statement of Policies for School Desegrega

tion Plans Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 .......... 22

Southern School Desegregation, 1966-67, a Report

of the U. S. Commission on Civil Rights, July,

1967 ........................................................ ..15n, 24n, 26,48n

Survey of School Desegregation in the Southern and

Border States, 1965-1966, U. S. Commission on Civil

Rights, February, 1966 ...... ..........................16n, 18n, 24n

U. S. Bureau of the Census. U. S. Census of Popula

tion: 1960 General Population Characteristics, Vir

ginia. Final Report PC (1)-48B 5n

I n the

i>ttprem£ ©curt nf the States

October T e e m , 1967

No. 695

C harles C. Gr e e n , et al.,

—v.—

Petitioner.*'

County S chool B oard of N ew K e n t County ,

V irg in ia , et al.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE PETITIONERS

Citations to Opinions Below

The District Court filed memorandum opinions on May-

17, 1966 and June 28, 1966. Both, unreported, are reprinted

appendix at pp. 47-48a and 53-61a. The June 12, 1967 Court

of Appeals opinions, reprinted appendix pp. 63-89a, are

reported at 382 F. 2d 326 and 338.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered

June 12, 1967, appendix p. 90a. Mr. Justice Black, on

September 8, 1967, extended time for filing the petition for

2

writ of certiorari until October 10, 1967 (91a). The petition

for certiorari was filed October 9, 1967 and was granted

December 11, 1967 (92a). The jurisdiction of this Court

is invoked under 28 U. S. C. Section 1254(1).

Question Presented

Whether—13 years after Brown v. Board of Education—

a school board discharges its obligation to conduct a unitary

non-racial school system, by adopting a freedom of choice

desegregation plan, where the evidence shows that such plan

is not likely to disestablish the dual system and where

there are other methods, no more difficult to administer,

which would immediately produce substantial desegrega

tion.

Constitutional Provision Involved

This case involves Section I of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

Statement

Petitioners seek review of the constitutional adequacy

of a freedom of choice desegregation plan adopted by

defendant School Board and approved by the Court below

en banc, Judges Sobeloff and Winter disagreeing with the

majority opinion.

I. The Pleadings

Petitioners, Negro parents and children of New Kent

County, Virginia, filed on March 15, 1965, in the United

States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia,

3

a class action seeking injunctive relief against the main

tenance of separate schools for the races. The complaint

named as defendants the County School Board, its indi

vidual members, and the Superintendent of Schools.1

The defendants filed, on April 5, 1965, a Motion to Dis

miss the complaint on the sole ground that it failed to state

a claim upon which relief could be granted (13a). In an

order entered on May 5, 1965, the district court deferred

ruling on the motion and directed the defendants to file

an answer by June 1, 1965 (14a). Defendants answered as

serting that plaintiffs were permitted under existing policy

(the pupil placement law) to attend the school of their

choice without regard to race, subject only to limitations

of space and denied that the court had jurisdiction to grant

any of the relief prayed (21-22a).

Thereafter, to comply with Title VI of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 241, and regulations of the United

States Department of Health, Education and Welfare, the

New Kent County School Board, on August 2,1965, adopted

a freedom of choice desegregation plan (to be placed into

effect in the 1966-67 school year) and on May 10, 1966 filed

copies thereof with the District Court.

1 The action was filed pursuant to 28 U. S. C. §1331 and §1343,

and 42 TJ. S. C. §1981 and §1983. The complaint alleged that

(7-8a) :

Notwithstanding the holding and admonitions in Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) and 349 U. S. 294

(1955), the defendant school hoard maintains and operates a

biracial school system. . . .

[that the defendants] ha[d] not devoted efforts toward initiat

ing non-segregation in the public school system, [and had failed

to make] a reasonable start to effectuate a transition to a

racially non-discriminatox-y school system as under paramount

law it [was] their duty to do.

4

II. The Plan A dopted by the Board

The plan provides essentially for “permissive transfers”

for 10 of the 12 grades. Only students eligible to enter

grades one and eight are required to exercise a choice of

schools. It provides further that “any student in grades

other than grades one and eight for whom a choice is not ob

tained will be assigned to the school he is now attending.” 2

It states that no choice will be denied other than for over

crowding in which case students living nearest the school

chosen will be given preference (34-4-Oa).

2 By failing to require, at least in its initial year, that every stu

dent make a choice, the plan permits some students to be assigned

under the former dual assignment system until approximately 1973.

Under the plan students entering other than grades one or eight

who do not exercise a choice are assigned to the school they are

then attending. Thus, a student, who began school in fall, 1965,

one year before the plan went into effect and was therefore assigned

to a school previously maintained for his race would, unless he

affirmatively exercised a choice to go elsewhere, be reassigned there

for the remainder of his elementary school years. Similarly, stu

dents who entered high school prior to 1966-67 under the old dual

assignment system, would, unless they took affirmative action to

transfer elsewhere, be reassigned to that school until graduation.

The plan, then, permits some students (those who began at a school

before it went into effect) to be reassigned for as long as up to

seven years (in the case of a first grader) to schools to which they

originally had been assigned on the basis of race. It need hardly

be said that such a plan—one which fails immediately to abolish

continued racial assignments or reassignments—may not stand

under Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 and 349 U. S.

294. The Fifth Circuit has rejected plans having that effect. See

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 372 F. 2d

836, 890-891, aff’d with modifications on rehearing en banc, 380 F.

2d 385, cert, denied sub nom. Caddo Parish School Board v. United

States, 389 U. S. 840, 19 L. Ed. 2d 103. We point this out only to

fully describe the workings of the plan. For overturning the deci

sion below7 on this ground would be insufficient to protect petitioners’

rights. As v7e more fully develop later wrhat is objectionable about

this plan is its employment of free choice assignment provisions to

perpetuate segregation in an area, -where, because of the lack of

residential segregation, it could not otherwise result.

5

III. The Evidence

New Kent is a rural county in Eastern Virginia, east

of the City of Richmond. There is no residential segrega

tion; both races are diffused generally throughout the

county3 (cf. PX “A” and “B” ; see also the opinion of

Judge Sobeloff at pp. 72a, 23a).4 5 There are only two public

schools in the county: New Kent, the formerly all-white

combined elementary and high school, and George W.

Watkins, an all-Negro combined elementary and high school.

Students f During the 1964-1965 school year some 1291

students (approximately 739 Negroes, 552 whites) were

enrolled in the school system. There were no attendance

zones. Each school served the entire county. Eleven Negro

buses canvassed the entire county to deliver 710 of the

740 Negro pupils to Watkins, located in the western half

of the county. Ten buses transported almost all of the

550 white pupils to New Kent in the eastern half (see PX

“A” and “B” and 24a, no. 4).

As the following table6 indicates, the Negro school was

more overcrowded and had a substantially higher pupil-

teacher ratio, and larger class sizes than the white school:

3 The Census reports show that the Negro population was sub

stantially the same in each of the four magisterial districts in New

Kent County: Black Creek—479, Cumberland—637, St. Peters—

633, and Weir Creek—565. See U. S. Bureau of the Census. V. 8.

Census of Population: 1960 General Population Characteristics,

Virginia. Pinal Report PC(1)-48B.

4 The prefix “PX” refers to plaintiffs’ exhibits. Exhibits “A” and

“B” show the bus routes for each of the two county schools. Because

of the difficulty in doing so, they have not been reproduced in the

appendix. Each exhibit shows the routes travelled by the various

buses bringing children to that particular school. Each school is

served by buses that traverse all areas of the county.

5 The information that follows was obtained from defendants’ an

swers to plaintiffs’ interrogatories (23-33a).

6 The data was compiled from 23-33a, in particular nos. 1-c, 1-f,

1-g, and 4.

6

Name of School

.Pupil-

Teacher

Eatio

Average

Class

Size

Overcrowding

Variance

From

Capacity

(Elem.

Grades

Number

Buses

Average

Pupils

Per Bus

New Kent

(white) 1-12 ....... 22 21 + 37 (9%) 10 54.8

George W. Watkins

(Negro) 1-12 .... 28 26 + 118 (28%) 11 64.5

From 1956 through the 1965-66 school year, school assign

ments of New Kent pupils were governed by the Virginia

Pupil Placement Act, §22-232.1 et seq. Code of Virginia,

1950 (1964 Replacement Volume), repealed by Acts of

Assembly, 1966, c. 590, under which any pupil could request

assignment to any school in the county; children making no

request were assigned to the school previously maintained

for their race.7 The free choice plan the Board adopted

in August, 1965 was not placed into effect until the 1966-

1967 school year by which time it had been approved by the

district court.

Despite their rights under the pupil placement procedure,

up to and including the 1964-1965 school year no Negro

pupil ever sought admission to New Kent and no white

7 Section 22-232.20 provided in p a r t:

“ . . . any child who wishes to attend a school other than the

school which he attended the previous year shall not be eligible

for placement in a particular school unless application is made

therefor . . . ”

Section 22-232.6 provided:

“After December 29, 1956, each school child who has heretofore

attended a public school and who has not moved from the

county, city or town in which he resided while attending such

school shall attend the same school which he last attended until

graduation therefrom unless enrolled for good cause shown, in

a different school by the Pupil Placement Board.”

7

pupil ever sought admission to Watkins (25a, no. 7). Al

though, as the following table shows, some Negro students

have since chosen to attend New Kent, no white pupil has

ever attended Watkins:

Student Body by Race8

Year N ew K ent Watkins

White Negro Other White Negro Other

1964-65 ...... .... 552 0 0 0 739 0

1965-66 .......... 555 35 0 0 691 0

1966-67 ...... .... 517 111 0 0 628 0

1967-68 ......____ 519 115 10 0 621 0

Thus, as late as 13 years after the decision in Brown,

85% of the Negro students in the county attend school only

with other Negroes.

Faculty. Teachers’contracts are for one year only. Until

the 1966-67 school year, the Board adhered to a policy of

assigning only white teachers to New Kent and only Negro

teachers to Watkins. Despite the declarations of the Board,

its policy has remained essentially unchanged as the fol

lowing table shows:

F aculty Composition by Race8 9

N ew K ent Watkins

W hite Negro White Negro

1964- 65 ______ 26 0 0 26

1965- 66 ______ 26 0 0 27

1966- 67 ______ 28.4 .4 0 27

1967- 68 ______ 28 .2 1 29.8

8 The record in this ease, like the records in all school desegrega

tion cases, is necessarily stale by the time it reaches this Court. In

this case the 1964-65 school year was the last year for which the

record supplied desegregation statistics. Information regarding stu

dent and faculty desegregation during the 1965-66, 1966-67 and

1967-68 school years was obtained from official documents, available

for public inspection, maintained by the United States Department

of Health, Education and Welfare. Certified copies thereof and an

accompanying affidavit have been filed with this Court and served

upon opposing counsel.

9 This information is taken from the HEW documents referred

to in Note 8, supra, and from number 1-f on 24a. Principals, li

brarians and other non-teaching personnel are not included.

8

In sum, during the current year, 1967-68, faculty in

tegration consists of the assignment of one full-time white

(of a total of 30.8 teachers) to Watkins and one part-time

(the equivalent of one day each week) Negro teacher to

New Kent. All the full-time teachers at that school are

still white.

IV. The D istrict Court’s Decision

On May 4, 1966, the case was tried before the District

Judge, Hon. John D. Butzner, Jr., who, on May 17, 1966,

entered a memorandum opinion and order: (a) denying

defendants’ motion to dismiss, and (b) deferring approval

of the plan pending the filing by the defendants of “an

amendment to the plan [which would provide] for em

ployment and assignment of staff on a non-racial basis”

(47-49a).

The Board filed on June 6, 1966, a supplement to its

plan dealing with school faculties (50a). On June 10, 1966,

plaintiffs filed exceptions to the supplement contending

(a) that the supplement failed to provide sufficiently for

faculty and staff desegregation, and (b) that plaintiffs

would continue to be denied constitutional rights under

the freedom of choice plan and that the defendants should

be required to assign students pursuant to geographic

attendance areas (52a).

On June 28, 1966, the district court entered a memo

randum opinion and an order approving the freedom of

choice plan as amended (53-62a).

V. The Court of A ppeals’ Opinion

On appeal to the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Cir

cuit petitioners contended that in view of the cireum-

9

stances in the county, the freedom of choice plan adopted

by the defendants was the method least likely to accomplish

desegregation and that the district court erred in ap

proving it.

On June 12, 1967, the Court, en banc, affirmed the dis

trict court’s approval of the freedom of choice assign

ment provisions of the plan, but remanded the case for

entry of an order regarding faculty “which is much more

specific and more comprehensive” and which would in

corporate in addition to a “minimal objective time table,”

some of the faculty provisions of the decree entered by

the Fifth Circuit in United States v. Jefferson County

Board of Education, supra (70-71a).

Judges Sobeloff and Winter concurred specially with

respect to the remand on the teacher issue but disagreed

on other aspects. Said Judge Sobeloff (71-72a) :10

I think that the District Court should be directed not

only to incorporate an objective time table in the

School Board’s plans for faculty desegregation, but

also to set up procedures for periodically evaluating

the effectiveness of the Boards’ “freedom-of-choice”

plans in the elimination of other features of a segre

gated school system.

# # * * #

. . . Since the Board’s “Freedom-of-choice” plan has

now been in effect for two years as to grades 1, 2,

8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 and one year as to all other grades,

10 This case was decided together with a companion case Bowman

v. County School Board of Charles City County, Virginia, No.

10793, for which no review is sought. While the opinion discussed

herein was rendered in the Charles City ease, it was expressly made

applicable to Neiv Kent (64a); similarly Judge Sobeloff stated that

his opinion in Charles City applied to New Kent (p. 71a). The

opinion in the Charles City case is at 65-89a.

1 0

clearly this court’s remand should embrace an order

requiring an evaluation of the success of the plan’s

operation over that time span, not only as to faculty

but as to pupil integration as well (73a).

While they did not hold, as petitioners had urged, that the

peculiar conditions in the county made freedom of choice

constitutionally unacceptable as a tool for desegregation

they recognized that it was utilized to maintain segregation

(76-77a):

As it is, the plans manifestly perpetuate discrimina

tion. In view of the situation found in New Kent

County, where there is no residential segregation, the

elimination of the dual school system and the establish

ment of a “unitary, non-racial system” could he readily

achieved with a minimum of administrative difficulty

by means of geographic zoning—simply by assigning

students living in the eastern half of the county to

the New Kent School and those living in the western

half of the county to the Watkins School. Although a

geographical formula is not universally appropriate,

it is evident that here the Board, by separately busing

Negro children across the entire county to the “Negro”

school, and the white children to the “white” school, is

deliberately maintaining a segregated system which

would vanish with non-racial geographic zoning. The

conditions in this county represent a classical case for

this expedient. (Emphasis added.)

While the majority implied that freedom of choice was

acceptable regardless of result, Judges Sobeloff and Winter

stated the test thus (79a):

1 1

“Freedom of choice” is not a sacred talisman; it is only

a means to a constitutionally required end—the aboli

tion of the system of segregation and its effects. If

the means prove effective, it is acceptable, but if it

fails to undo segregation, other means must be used

to achieve this end.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Brown condemned not only compulsory racial assign

ments of public school children, but required “a transition

to a racially non-diseriminatory system.” That goal is not

achieved if some schools are still maintained or identifiable

as being for Negroes and others for whites. It cannot be

achieved until the racial identification of schools, con

sciously imposed by the state during the era of enforced

segregation, has been erased. The specific direction in

Brown II and general equitable principles require that

school districts formerly segregated by law, employ af

firmative action to achieve this end.

If the time for deliberate speed has indeed ended, as this

Court has said (Note 38, infra), lower courts must now

fashion decrees which, consistent with educational and

equitable principles, will speedily and effectively disestab

lish the dual system thereby achieving the unitary non-

racial system mandated by the Constitution. That was not

done here.

Freedom of choice desegregation plans typically leave the

dual system undisturbed. The overwhelming majority of

school districts in Brown-affected states have adopted

such plans (Note 18, infra) and available statistics demon

1 2

strate that they have not disestablished the dual system

(infra, pp. 26-27). At best, such plans leave one segment,

the Negro segment, intact (Ibid.). Yet, most, but not all,

lower courts have not responded to the obvious: such plans

are not only wasteful and inefficient, but by nature are in

capable of effectuating that transition.

Lengthy related experience under the Virginia Pupil

Placement Law demonstrated that plans under which stu

dents assign themselves were not likely to disestablish the

dual system in New Kent County. Petitioners, moreover,

furnished uncontradicted evidence that another method,

more feasible to administer would immediately disestab

lish the dual system. Nonetheless, the Board failed to offer

any reasons justifying delay in achieving a unitary non-

racial system. There was no suggestion that administra

tive difficulties would preclude the division of the county

into two school attendance areas or the assignment of

elementary school pupils to one school and high school

students to the other.

Where alternative means of immediate accomplish

ment of a unitary non-racial school system are so readily

available, judicial approval of free choice is constitution

ally impermissible.

13

A R G U M E N T

I.

Introduction

The question here is whether in the late sixties, a full

generation of public school children after Brown v. Board

of Education,11 school boards may employ so-called free

dom of choice desegregation plans which perpetuate ra

cially identifiable schools, where other methods, equally or

more feasible to administer, will more speedily disestab

lish the dual systems.

Other plans or programs, similarly ineffective where

adopted, are under review in Monroe v. Board of Com

missioners of the City of Jackson, Term., No. 740, and

Raney v. The Board of Education of the Gould School

District, No. 805.12 The controversies in all three cases

concern the precise point at which a school board has ful

filled its obligations under Brown; and all three present

for determination the question whether school districts for

merly segregated by law must employ affirmative action

to erase state-imposed racial identification of their schools.

The most marked and widespread innovation in school

administration in southern and border states in the last

fifty years has been the change in pupil assignment method

in the years since Brown,13 from geographic attendance

11 347 U. S. 483 (Brown I ) ; 349 U. S. 294 (Brown II).

12 All three cases will be argued together. See 36 U. S. L. W. 3286

(U. S. Jan. 15,1968).

13 See generally, Campbell, Cunningham and MePhee, The Or

ganization and Control of American Schools, 1965. (“As a conse

quence of [Brown v. Board of Education, supra], the question of at

tendance areas has become one of the most significant issues in

American education of this Century” (at 136).)

14

zones to so-called “free choice.” Prior to Brown, systems

in the north and south, with rare exception, assigned pupils

by zone lines around each school.14

Under an attendance zone system, unless a transfer is

granted for some special reason, students living in the zone

of the school serving their grade would attend that school.

Prior to the relatively recent controversy concerning seg

regation in large urban systems, assignment by geographic

attendance zones was viewed as the soundest method of

pupil assignment. This was not without good reason; for

placing children in the school nearest their home would

often eliminate the need for transportation, encourage the

use of schools as community centers and generally facili

tate planning for expanding school populations.15

In states where separate systems were required by law,

this method was implemented by drawing around each

white school attendance zones for whites in the area, and

around each Negro school zones for Negroes. In many

14 “In the days before the impact of the Brown decision began to

be felt, pupils were assigned to the school (corresponding, of course

to the color of the pupils’ skin) nearest their homes; once the school

zones and maps had been drawn up, nothing remained but to in

form the community of the structure of the zone boundaries.” Ven-

trees Moses v. Washington Parish School Board,----- P. Supp.____

(slip op. 15-16) (E. D. La. 1967), discussed infra, p. 19. See also

Meador, The Constitution and the Assignment of Pupils to Public

School, 45 Ya. L. Rev. 517 (1959), “until now the matter has been

handled rather routinely almost everywhere by marking off' geo

graphical attendance areas for the various buildings. In the South,

however, coupled with this method has been the factor of race.”

15 Campbell, Cunningham and MePhee, supra, Note 13 at 133-

144.

By showing that zone assignment was the norm prior to Brown,

we intend merely to indicate the background against which free

choice was developed. We do not suggest that the use of zones is

always the most desirable method of pupil assignment.

15

areas, as in the ease before the Court where the entire

county was a zone, lines overlapped because there was no

residential segregation. Thus, in most southern school dis

tricts, school assignment was largely a function of three

factors: race, proximity and convenience.

After Brown, southern school boards were faced with

the problem of “effectuating a transition to a racially non-

discriminatory system” (Brown II at 301). The easiest

method, administratively, was to convert the dual attend

ance zones into single attendance zones, without regard

to race, so that assignment of all students would depend

only on proximity and convenience.16 With rare exception,

however, southern school boards, when finally forced to

begin desegregation, rejected this relatively simple method

in favor of the complex and discriminatory procedures of

pupil placement laws and, when those were invalidated,17

switched to what has in practice worked the same way—

so-called free choice.18

16 Indeed, it was to this method that this Court alluded in Brown

I I when it stated “ [t] o that end, the courts may consider problems

related to administration, arising from . . . revision of school dis

tricts and attendance areas into compact units to achieve a system

of determining admission to the public schools on a non-racial basis”

(349 U. S. at 300-301).

17 For cases invalidating or disapproving such laws, see North-

cross v. Board of Education of the City of Memphis, 302 F. 2d 818

(6th Cir., 1962); Gibson v. Board of Public Instruction of Dade

County, 272 F. 2d 763 (5th Cir., 1959); Manning v. Board of

Public Instruction of Hillsboro County, 277 F. 2d 370 (5th Cir.,

1960) ; Dove v. Parham, 282 F. 2d 256 (8th Cir., 1960).

18 According to the Civil Rights Commission, the vast majority of

school districts in the south use freedom of choice plans. See

Southern School Desegregation, 1966-67, A Report of the U. S.

Commission on Civil Rights, July, 1967. The report states, at pp

45-46:

Free choice plans are favored overwhelmingly by the 1,787

school districts desegregating under voluntary plans. All such

16

In Virginia, the freedom of choice concept was resorted

to after the state’s “massive resistance” 19 measures had

failed.20 The Pupil Placement Board, first created by legis

lation approved September 29, 195621 placed no Negro child

in any white school until after the June 28. 1960 decision in

Farley v. Turner, 281 F. 2d 131 (4th Cir.). During the

next two years, 1960-61 and 1961-62, that board conducted

individual hearings in the cases of those Negro children

and their families who, having protested against assign

ments to Negro schools and having had the fact of such

districts in Alabama, Mississippi, and South Carolina, without

exception, and. 83% of such districts in Georgia have adopted

free choice plans. . ..

The great majority of districts under court order also are

employing “freedom of choice.”

See also Survey of School Desegregation in the Southern and

Border States, 1965-1966, United States Commission on Civil

Rights, February, 1966, at p. 47.

19 In National Association for the Advancement of Colored Peo

ple v. Patty, 159 F. Supp. 503, 511, Judge Soper discusses the

legislative history of the massive resistance program.

20 The State statute requiring the closing of any public school

wherein both white and Negro children might otherwise be enrolled

was invalidated on January 19, 1959 in Harrison v. Day, 200 Va.

439,106 S. E. 2d 636. See also, James v. Almond, 170 F. Supp. 331

(E. D. Va. 1959) (three-judge court); but not until after one or

more schools had been closed in Norfolk (see James v. Almond, 170

F. Supp. 331) (E. D. Va. 1959), in Charlottesville (see School

Board of City of Charlottesville v. Allen, 263 F. 2d 295 (4th Cir.

1959)) and in Warren County (see Governor’s proclamation re

ported in 3 Race Rel. L. Rep. 972); and the threat of closed schools

had effectively deterred desegregation in Arlington County (see

Hamm v. County School Board of Arlington County, 264 F. 2d 945,

946 (4th Cir. I960)).

21 Chapter 70, Acts of Assembly, 1956, Extra Session, codified as

§22-232.1 et seq. of the Code of' Virginia 1950, 1964 Repl. Vol.

(repealed by Acts 1966, c. 590).

17

protest publicized in the local newspaper, were subjected

to tests and other criteria not required of white children.

The unconstitutionality of such discriminatory practices

was declared in Green v. School Board of the City of

Roanoke, 304 F. 2d 118 (4th Cir. 1962) and Marsh v. County

School Board of Roanoke County, 305 F. 2d 94 (4th Cir.

1962). Thereafter,22 the timely applications for the assign

ment of Negro children to named schools attended by their

white neighbors were routinely granted23 except in a few

communities where boundaries for school attendance zones

have been drawn around racially segregated residential

areas.24

Under so-called free choice students are allowed to at

tend the school of their choice. Most often they are per

mitted to choose any school in the system. In some areas,

they are permitted to choose only either the previously

all-Negro or previously all-white school in a limited geo

graphic area. Not only are. such plans more difficult to

administer (choice forms have to- be processed and stand

ards developed for passing on them, with provision for

22 See United States v. County School Board of Prince George

County, Va., 221 F. Supp. 93, i05 (E. D. Va. 1963), viz.: “The

Pupil Placement Board suggested in oral argument that this suit

is premature because recently the Board has adopted a policy of

assigning Negro applicants to schools attended by white children

without, regard to academic achievement or residence requirements

different from those required of white children.” (Emphasis

added.)

23 See, e.g., Pettaway v. County School Board of Surry County,

Virginia, 230 F. Supp. 480 (E. D. Va. 1964), modified and re

manded, 339 F. 2d 486 (4th Cir.); Franklin v. County School

Board of Giles County, Virginia, 242 F. Supp. 371 (W. D. Va.

1965) reversed 360 F. 2d 325 (4th Cir. 1966).

24 See, e.g., Gilliam v. School Board of the City of Hopewell,

Virginia, 345 F. 2d 325 (4th Cir. 1965), remanded 382 IT. S 103

(1965).

18

notice of the right to choose and for dealing with students

who fail to exercise a choice),25 they are, in addition,—as

experience demonstrates (infra pp. 25-27)—far less likely

to disestablish the dual system.

25 Section II of the decree appended by the United States Court

of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, to its recent decision in United

States v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 372 F. 2d 836, aff’d

with modification on rehearing en banc, 380 F. 2d 385, cert, denied

sub nom. Caddo Parish School Board v. United States, 389 U. S.

840, 19 L. Ed. 2d 103, shows the complexity of such plans. That

Court had previously described such plans as a “haphazard basis”

for the administration of schools. Singleton v. Jackson Municipal

Separate School District, 355 F. 2d 865, 871 (5th Cir. 1966).

Under such plans generally, and under the plan in this case,

school officials are required to mail (or deliver by way of the

students) letters to the parents informing them of their rights to

choose within a designated period, compile and analyze the forms

returned, grant and deny choices, notify students of the action

taken and assign students failing to choose to the schools nearest

their homes. Virtually each step of the procedure, from the initial

letter to the assignment of students failing to choose, provides an

opportunity for individuals hostile to desegregation to forestall its

progress, either by deliberate mis-performance or non-performance.

The Civil Eights Commission has reported on non-compliance by

school authorities with their desegregation plans:

In Webster County, Mississippi, school officials assigned on a

racial basis about 200 white and Negro students wThose freedom

of choice forms had not been returned to the school office, even

though the desegregation plan stated that it was mandatory

for parents to exercise a choice and that assignments would be

based on that choice [footnote omitted]. In McCarty, Missouri

after the school board had distributed freedom of choice forms

and students had filled out and returned the forms, the board

ignored them.

Survey of School Desegregation in the Southern and Border States,

1965-1966, at p. 47. Given the other shortcomings of free choice

plans, there is serious doubt whether the constitutional duty to effect

a non-racial system is satisfied by the promulgation of rules so sus

ceptible of manipulation by hostile school officials. As Judge So-

beloff has observed:

A procedure which might well succeed under sympathetic ad

ministration could prove woefully inadequate in an antagonis

tic environment.

Bradley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, 345 F. 2d 310

(4th Cir. 1965) (concurring in part and dissenting in part).

19

Only recently a district court, in what has proved to be

the most important judicial scrutiny of free choice plans,

observed (Moses v. Washington Parish School Board, ——

F. Supp. —— (E. D. La., October 19, 1967):

Free choice systems, as every southern school official

knows, greatly complicate the task of pupil assign

ment in the system and add a tremendous workload

to the already overburdened school officials (----- F.

Supp. ----- ; Slip Op. 15).

If this Court must pick a method of assigning stu

dents to schools within a particular school district,

barring very unusual circumstances, we could imagine

no method more inappropriate, more unreasonable,

more needlessly wasteful in every respect, than the

so-called “free-choice” system. (Emphasis added.)

(Id. at 21)

* # * # ^

Under a “free-choice” system, the school board can

not know or estimate the number of students who will

want to attend any school, or the identity of those

who will eventually get their choice. Consequently,

the board cannot make plans for the transportation of

students to schools, plan curricula, or even plan such

things as lunch allotments and schedules; moreover,

since in no case except by purest coincidence will an

appropriate distribution of students result, and each

school will have either more or less than the number

it is designed to efficiently handle, many students at

the end of the free-choice period have to be reassigned

to schools other than those of their choice—this time

on a strict geographical-proximity basis, see the Jeffer

2 0

son County decree, thus burdening the board, in the

middle of what should be a period of firming up the

system and making final adjustments, with the awe

some task of determining which students will have to

be transferred and which schools will receive them.

Until that final task is completed, neither the board

nor any of the students can be sure of which school

they will be attending; and many students will in the

end be denied the very “free choice” the system is

supposed to provide them. (Id. at 21-22)

Although the court never explicitly answers its own ques

tion—why was the Washington .Parish Board willing to

undergo the uncertainty and unreasonable burdens imposed

by such a system (slip. op. at 21-22)—it ordered the aban

donment of free choice and, in its place the institution of

a geographical zoning plan.26

Under free choice plans, the extent of actual desegre

gation varies directly with the number of students seek

26 As we more fully develop infra pp. 23-25, we think the answer

obvious: that the Washington Parish Board, and indeed most

boards, adopted free choice knowing and intending that it would

result in fewer Negro students in white schools and, conversely,

fewer (if any at all) white students in Negro schools, than would

otherwise result under a rational non-racial system of pupil assign

ment.

To be sure, a free choice plan might make some sense, as Judge

Heebe recognized, in the context of grade by grade desegregation

and where all grades in a given building had not yet been reached

(Id. at 18-19). In such circumstances, it might indeed have been

easier to assign by “choices” rather than have to draw new zones for

each building each time a new grade level was reached under the

plan. But, as Judge Heebe pointed out, “the usefulness of such

plans logically ended with the end of the desegregation process

[when the plan reached all grades]” (Ibid.). Thus, even conceding

some interim usefulness for free choice, in some other situation, it

was entirely out of place in New Kent County which desegregated

all grades at the time the plan was approved and which had but two

schools.

2 1

ing, and actually being permitted to transfer to schools

previously maintained for the other race. It should have

been obvious, however, that white students—in view of

general notions of Negro inferiority and that far too often

Negro schools are vastly inferior to those furnished whites27

—would not transfer to formerly Negro schools; and, in

deed, very few have.28 Thus, from the beginning the burden

of disestablishing the dual system under free choice was

thrust upon the Negro children and their parents, despite

this Court’s admonition in Brown II (349 IT. S. 294, 299)

that “school authorities had the primary responsibility.”

That is what happened in this case. Although the majority

stated that (66a):

The burden of extracting individual pupils from dis

criminatory, racial assignments may not be cast upon

the pupils or their parents [and that] it is the duty

27 Watkins, the Negro school in New Kent County was more over

crowded and had substantially larger class sizes and teacher-pupil

ratios than did the white school. (See p. 6, supra.)

The Negro schools in the South compare unfavorably to white

schools in other important respects. In Equality of Educational

Opportunity, a report prepared by the Office of Education of the

United States Department of Health Education and Welfare pur

suant to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Commissioner states, con

cerning Negro schools in the Metropolitan South (at p. 206) :

The average white attends a secondary school that, compared

to the average Negro is more likely to have a gymnasium, a

foreign language laboratory with sound ecpiipment, a cafeteria,

a physics laboratory, a room used only for typing instruction,

an athletic field, a chemistry laboratory, a biology laboratory,

at least three movie projectors.

Essentially the same was said of Negro schools in the non-metropoli

tan South (Id. at 210-211). I t is not surprising, therefore, quite

apart from race, that white students have unanimously refrained

from choosing Negro schools.

28 “During the past school year, as in previous years, white stu

dents rarely chose to attend Negro schools.” Southern School De

segregation, 1966-67 at p. 142, United States v. Jefferson County

Board of Education, supra, 372 F. 2d at 889.

2 2

of the school boards to eliminate the discrimination

which inheres in such a system [,]

the very plan the court approved did just that. To be sure

each pupil was given the unrestricted right to attend any

school in the system. But, as previously noticed, desegre

gation never occurs except by transfers by Negroes to

the white schools. Thus, the freedom of choice plan ap

proved below, like all other such plans, placed the burden

of achieving a single system ujjon Negro citizens.

The fundamental premise of Brown I was that segrega

tion in public education had very deep and long term

effects. It was not surprising, therefore, that individuals

reared in that system and schooled in the ways of sub

servience (by segregation, not only in schools, but in every

other conceivable aspect of human existence) when asked

to “make a choice,” chose, by inaction, that their children

remain in the Negro schools. In its Revised Statement of

Policies for School Desegregation Plans Under Title VI

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (hereinafter referred to as

Revised Guidelines), the Department of Health, Education

and Welfare states (45 C.F.R. Part 181.54):

A free choice plan tends to place the burden of

desegregation on Negro or other minority group stu

dents and their parents. Even when school authorities

undertake good faith efforts to assure its fair opera

tion, the very nature of a free choice plan and the

effect of longstanding community attitudes often tend

to preclude or inhibit the exercise of a truly free choice

by or for minority group students. (Emphasis added.)

Beyond that, by making the Negro’s exercise of choice the

critical factor upon which the conversion depended, school

23

authorities virtually insured its failure. Every community

pressure militates against the affirmative choice by Negro

parents of white schools.29 Moreover, intimidation of Ne

groes, a weapon well-known throughout the south, could

equally be employed to deter them from seeking transfers

to white schools. At best, school officials must have rea

soned, only a few hardy souls would venture from the

more comfortable atmosphere of the Negro school, with

their all-Negro faculties and staff.30 Those that “dared,”

would soon be taught their place.31

29 Compare the following (M. Hayes Mizell, The South Has Gen

uflected and Held on to Tokenism, Southern Education Report, Vol.

3, No. 6 (January/February, 1968), at p. 19) :

Freedom of choice . . . has not brought significant school deseg

regation . . . simply because it is a policy which has proved too

fragile to withstand the political and social forces of Southern

life. The advocates of freedom of choice assumed that school

desegregation would somehow be insulated from these forces

while, in reality, it was central to them.

In embracing the freedom of choice plan Southern school

systems understood, even if HEW did not, that man’s choices

are not made within a vacuum, but rather they are influenced

by the sum of his history and culture.

30 “Negro students who choose white schools are, as we know from

many cases, only Negroes of exceptional initiative and fortitude.”

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education, supra, 372

F. 2d at 889.

31 A good example is Coppedge v. Franklin County Board of

Education, 273 F. Supp. 289 (E. D. N. C. 1967), appeal pending.

The Court found that there was marked hostility to desegregation

in Franklin County, that Negroes had been subjected to violence,

intimidation and reprisals, and that each successive year under the

freedom of choice plan it had approved earlier had resulted in

fewer requests by Negroes for reassignment to formerly all-white

schools. Concluding that (Id. at 296) :

Community attitudes and pressures . . . have effectively inhib

ited the exercise of free choice of schools by Negro pupils and

their parents

the Court directed that the defendants

prepare and submit to the Court, on or before October 15th,

1967, a plan for the assignment, at the earliest practicable date,

24

Nor were they mistaken. Tlie Civil Eights Commission,

in its most recent reports on school desegregation in

Brown-affected states, reports exhaustively of the violence,

threats of violence and economic reprisals to which Ne

groes have been and are subjected to deter them from

placing their children in white schools.32 That specific

of all students upon the basis of a unitary system of non-racial

geographic attendance zones, or a plan for the consolidation of

grades, or schools, or both (Id. at 299-300).

32 Southern School Desegregation, 1966-67 at pp. 45-69; Survey

of School Desegregation in the Southern and Border States, 1965-

66, at pp. 55-66. To relate but a few of the numerous instances of

intimidation upon which the Commission reported: the 1966-67

study quotes the parents of a 12 year old boy in Clay County,

Mississippi as saying (at p. 48) :

white folks told some colored to tell us that if the child went

[tO' a white school] he wouldn’t come back alive or wouldn’t

come back like he went.

In Edgecombe County, North Carolina, the home of a. Negro couple

whose son and daughter were attending the formerly all-white

school was struck by gunfire (50). In Dooly County, Georgia, the

father of a 14 year old boy, who had filled out his own form and

attended the formerly white school, reported that “that Monday

night the man [owner] came and said ‘I want my damn house by

Saturday’ ” (52).

The Commission made the following findings, in its 1966-67 re

port (atp . 88):

6. Freedom of choice plans, which have tended to perpetu

ate racially identifiable schools in the Southern and Border

States, require affirmative action by both Negro and white

parents and pupils before such disestablishment can be

achieved. There are a number of factors which have prevented

such affirmative action by substantial numbers of parents and

pupils of both races:

(a) Fear of retaliation and hostility from the white com

munity . . .

(b) [V]iolence, threats of violence and economic reprisal by

white persons, [and the] harassment of Negro children by

white classmates . . .

(c) [improper influence by public officials].

(footnote continued on following page)

25

episodes do not occur to particular individuals hardly pre

vents them from learning of them and acting on that knowl

edge.

With rare exception, then, school officials adopted, and

the lower courts condoned, free choice knowing that it

would produce fewer Negro students in white schools, and

less injury to white sensibilities than under the geographic

attendance zone method. Their expectations were justified.

Meaningful desegregation has not resulted from the use of

free choice. Even when Negroes have transferred, how

ever, desegregation has been a one-way street—a few

Negroes moving into the white schools, but no whites trans

ferring to Negro schools. In most districts, therefore, as

here, the vast majority of Negro pupils continue to attend

school only with Negroes.

Although the proportion of Negroes in all-Negro schools

has declined since Brown, more Negro children are now

attending such schools than in 1954.83 Indeed, during the

1966-67 school year, a full 12 years after Brown, more

than 90% of the almost 3 million Negro pupils in the 11

Southern states still attended schools which were over

95% Negro and 83.1% were in schools which were 100%

Negro.* 34 And, in the case before the Court, 85% of the

Negro pupils in New Kent County still attend schools with

(dj Poverty. . . . Some Negro parents are embarrassed to

permit their children to attend such schools without suitable

clothing. In some districts special fees are assessed for courses

which are available only in the white schools ;

(e) Improvements . . . have been instituted in all-Negro

schools . . . in a manner that tends to discourage Negroes from

selecting white schools.

:,s Southern School Desegregation, 1966-67, at p. 8.

Id. at 103.

26

only Negroes. “This June, the vast majority of Negro

children in the South who entered the first grade in 1955,

the year after the Brown decision, were graduated from

high school without ever attending a single class with a

single white student.” 33 Thus, as the Fifth Circuit has

said, “ [f]or all but a handful of Negro members of the

High School Class of 1966, this right [to equal educational

opportunities with white children in a racially non-dis-

criminatory public school system] has been ‘of such stuff

as dreams are made on.’ ” 35 36

In its most recent report, the Civil Eights Commission

states (Southern School Desegregation, 1966-67, at p. 3 ) :

. . . the slow pace of integration in the Southern and

border states was attributable in large measure to the

fact that most school districts in the South had adopted

so-called “free choice plans” as the principal method

of desegregation . . .

The review of desegregation under freedom of choice

plans contained in this report, and that presented in

last year’s Commission’s survey of southern school de

segregation, shows that the freedom of choice plan is

inadequate in the great majority of cases as an in

strument for disestablishing a dual school system. Such

plans have not resulted in desegregation of Negro

schools and therefore perpetuate one-half of the dual

school system virtually intact (Id, at 94).

* # # # *

35 Id. at 90-91.

36 United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education, supra,

372 F. 2d 836 at 845.

27

Freedom of choice plans . . . [have] failed to dis

establish the dual school systems in the Southern and

border states . . . [Id. at 3].37

II.

A Freedom of Choice Plan Is Constitutionally Unac

ceptable Where There Are Other Methods, No More

Difficult to Administer, Which Would More Speedily

Disestablish the Dual System.

The duty of a school board under Brown, in the late

sixties is to adopt that plan which will most speedily ac

complish the effective desegregation of the system. By

now, the time for “deliberate speed” has long run out.38 We

concede that a court should not enforce its will where

37 HEW has apparently reached the same conclusion. According

to the Director of its Office of Civil Rights, F. Peter Libassi, “ [free

dom of choice] . . . often doesn’t finish the job. of eliminating the

dual school system. We had to follow the freedom of choice plan

to prove its ineffectiveness, and this was the year that it did prove

its ineffectiveness, so that now we’re ready to move into the next

phase.” N. Y. Times, Sep.t. 24, 1967, at p. 57. And, in the Palm

Beach Post-Times of Oct. 8, 1967 at p. B-7, he was reported to have

said, “you can’t eliminate the dual system by free choice.”

In an earlier report, Facial Isolation in the Public Schools, the

Civil Rights Commission observed (at p. 69) that, “ . . . the degree

of school segregation in these free-choice systems remains high,” and

concluded that (ibid,.) : “only limited school desegregation has been

achieved under free choice plans in Southern and Border city school

systems.”

38 Almost two years ago this Court stated, “more than a decade

has passed since we directed desegregation of public school facilities

with all deliberate speed. . . . Delays in desegregating school systems

are no longer tolerable.” Bradley v. School Board of The City of

Richmond, 382 U. S. 103, 105. “There has been entirely too much

deliberation and not enough speed . . . ” Griffin v. County School

Board of Prince Edward County, 377 U. S. 218, 229. “The time for

more ‘deliberate speed’ has run out . . . ” Id. at 234. Cf. Watson

v. Memphis, 373 U. S. 526, 533.

2 8

alternative methods are not likely to produce dissimilar

results—that much discretion should still be the province

of the school board. We submit, however, that a court may

not—at this late date, in the absence of persuasive evidence

showing the need for delay—permit the use of any plan

other than that which will most speedily and effectively

disestablish the dual system. Put another way, at this point,

that method must be mandated which will do the job more

quickly and effectively.

A. The Obligation of a School B oard Under B rown v.

B oard of Education Is to Disestablish the Dual

School System and to Achieve a Unitary, Non-racial

System .

1. The Fourth Circuit’s Adherence to Briggs.

At bottom, this controversy concerns the precise point

at which a school board has fulfilled its obligations under

Brown I and II. When free choice plans initially were con

ceived, courts generally adhered—mistakenly, we submit—

to the belief that it was sufficient, to permit each student an

unrestricted free choice of schools. It was said that “de

segregation” did not mean “integration” and that the

availability of a free choice of schools, unencumbered by

violence and other restrictions, was sufficient quite apart

from whether any integration actually resulted. (The doc

trine probably had its genesis in the now famous dictum

of Judge Parker in Briggs v. Elliot, 132 F. Supp. 776, 777

(E. I). S. C. 1955), “The Constitution . . . does not require

integration. It merely forbids segregation.” 39) Despite

39 See generally Jeffers v. Whitley, 309 F. 2d 621, 629 (4th Cir.

1962); Borders v. Bippy, 247 F. 2d 268, 271 (5th Cir. 1957); Boson

v. Bippy, 285 F. 2d 43, 48 (5th Cir. 1960); Vick v. Board of Edu

cation of Obion County, 205 F. Supp. 436 (W. D. Tenn. 1962);

Kelley v. Board of Education of the City of Nashville, 270 F. 2d

209,229 (6th Cir. 1959).

29

its protestations, the majority below manifested much of

this thinking (66-67a, 68a):

Employed as descriptive of a system of permissive

transfers out of segregated schools in which the initial

assignments are both involuntary and dictated by racial

criteria [freedom of choice], is an illusion and an op

pression which is constitutionally impermissible . . .

Employed as descriptive of a system in which each

pupil, or his parents, must annually" exercise an un

inhibited choice, and the choices govern the assign

ments, it is a very different thing.

* * * # #

Since the plaintiffs here concede that their annual

choice is unrestricted and unencumbered, we find in its

existence no denial of any constitutional right not to be

subjected to racial discrimination. [Emphasis added.]

At no point in its ojhnion did the majority meet the

essence of petitioners’ claim—that in view of related ex

perience under the pupil placement law, there was no good

reason to believe that free choice would, in fact, desegre

gate the system and that the district court should have

mandated the use of geographic zones which, on the evidence

before it, would produce greater desegregation. The opin

ion, in true Briggs form, neither states nor implies a re

quirement that the plan actually “work.” The most it can be

read to say is that while Negroes rightfully may complain

if extraneous circumstances inhibit the making of a “truly 40

40 Contrary to the court’s statement, the plan did not require

that “each pupil or his parents must annually exercise [a] choice.”

See Note 2, supra.

30

free choice,” they have no basis to complain and the Con

stitution is satisfied if no such circumstances are shown.41

2 . B ro w n C o n tem p la ted C om ple te R eo rg an iza tio n ,

The notion that the making available of an ostensibly

unrestricted choice satisfies the Constitution, quite apart

from whether significant numbers of white students choose

Negro schools or Negro students white schools, is funda

mentally inconsistent with Brown I and II, Bolling v.

Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497, Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, Brad

ley v. School Board of the City of Richmond, 382 II. S. 103

and other decisions of this Court.42 Brown, in our view,

condemned not only compulsory racial assignments but

also, more generally, the maintenance of a dual public

school system based on race—where some schools are

maintained or identifiable as being for Negroes and others

for whites. It presupposed major reorganization of the

educational systems in affected states. The direction in

Brown II, to the district courts demonstrates the thorough

41 This is not an overharsh reading of the opinion. Only recently

a writer observed:

The Fourth is apparently the only circuit of the three that

continues to cling to the doctrine of Briggs v. Elliot, and em

braces freedom of choice as a final answer to school desegrega

tion in the absence of intimidation and harassment.

See Dunn, Title VI, The Guidelines and School Desegregation in

the South, 53 Va. L. Rev. 42, 72 (1967). Judge Sobeloff perceived

this and exhorted the majority to “move out from under the in

cubus of the Briggs v. Elliot dictum and take [a] stand beside the

Fifth and Eighth Circuits” (89a). Cf. Swann v. Charlotte Meck

lenburg Board of Education, 369 F. 2d 29 (4th Cir. 1966) where

essentially the same philosophy—that a desegregation plan need not

result in actual integration—was expressed in a case involving geo

graphic zones.

42 See Rogers v. Paul, 382 U. S. 198; Calhoun v. Latimer, 377

U. S. 263; Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, 377 U. S. 218; Goss v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 683.

31

ness of the reorganization envisaged. They were held to

consider:

problems related to administration, arising from the

physical condition of the school plant, the school trans

portation system, personnel, revision of school districts

and attendance areas into compact units to achieve a

system of determining admission to the public schools

on a non-racial basis, and revision of local laws and

regulations which may be necessary in solving the

foregoing problems (349 U. S. at 300-301).43 *

If a “racially non-discriminatory system” could be

achieved with Negro and white students continuing as be

fore to attend schools designated for their race, none of the

quoted language was necessary. It would have been suffi

cient merely to say “compulsory racial assignments shall

cease.” But the Court did not stop there. It ordered, rather,

a pervasive reorganization which would transform the sys

tem into one that was “unitary and non-racial,” one, in other

words, in wdiieh schools would no longer be identifiable as

being for Negroes or whites.

That students have been permitted to choose a school

does not destroy its racial identification if it previously

was designated for one race, continues to serve students of,

and is staffed solely by, teachers of that race. The only

way the racial identification of a school—consciously im

posed by the state during the era of enforced segregation

—can be erased is by having it serve students of botli races,

through teachers of both races. Only when racial identifica

tion of schools has thus been eliminated will the dual sys

tem have been disestablished.

43 Much the same was implied in Cooper v. Aaron, supra, at 358

U. S. 7: “state authorities were thus duty bound to devote every

effort toward initiating desegregation . . . ”

32

3. Case and Statutory Law.

Decisional and statutory44 law support this reading of

Brown. Only two—the Fourth and the Sixth45—of the six

44 Dissatisfied with the snail’s pace of southern school desegrega

tion (caused mainly by the early approval by the lower courts of

pupil placement laws and, when they were invalidated as admin

istered, by judicial acceptance of free choice), Congress enacted

Titles IV (42 U. S. C. 2000-c et seq.) and VI (42 U. S. C. 2000-d

et seq. (1964)) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Pursuant to Title VI, the Department of Health, Education and

Welfare adopted a series of “Guidelines,” for school districts de

segregating pursuant to Brown. In its most recent—the Revised

Guidelines, dated December, 1966—the Department has taken the

position that desegregation plans must work—result in actual in

tegration. Under these Guidelines, the Commissioner has the power,

where the results under a free choice plan continue to be unsatis

factory, to require, as a precondition to the making available of

further federal funds, that the school system adopt a different type

of desegregation plan. Revised Guidelines, 45 CFR 181.54. Al

though administrative regulations propounded under Title VI of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964 are not binding on courts determining

private rights under the Fourteenth Amendment, nonetheless they

are entitled to great weight in the formulation by the judiciary

of constitutional standards. See Skidmore v. Swift & Co., 323

U. S. 134, 137, 139-140; United States v. American Trucking

Associations, Inc., 310 U. S. 534; Norwegian Nitrogen Products Co.

v. United States, 288 U. S. 294; United States v. Jefferson County

Board of Education, supra, 380 F. 2d at 390.

That HEW accepts free choice plans as establishing the eligibility

of a district for federal aid does not, of course, mean that such

plans are constitutional. The available evidence indicates that

HEW has approved such plans, despite the massive evidence of

their inability to disestablish the dual system, only because they