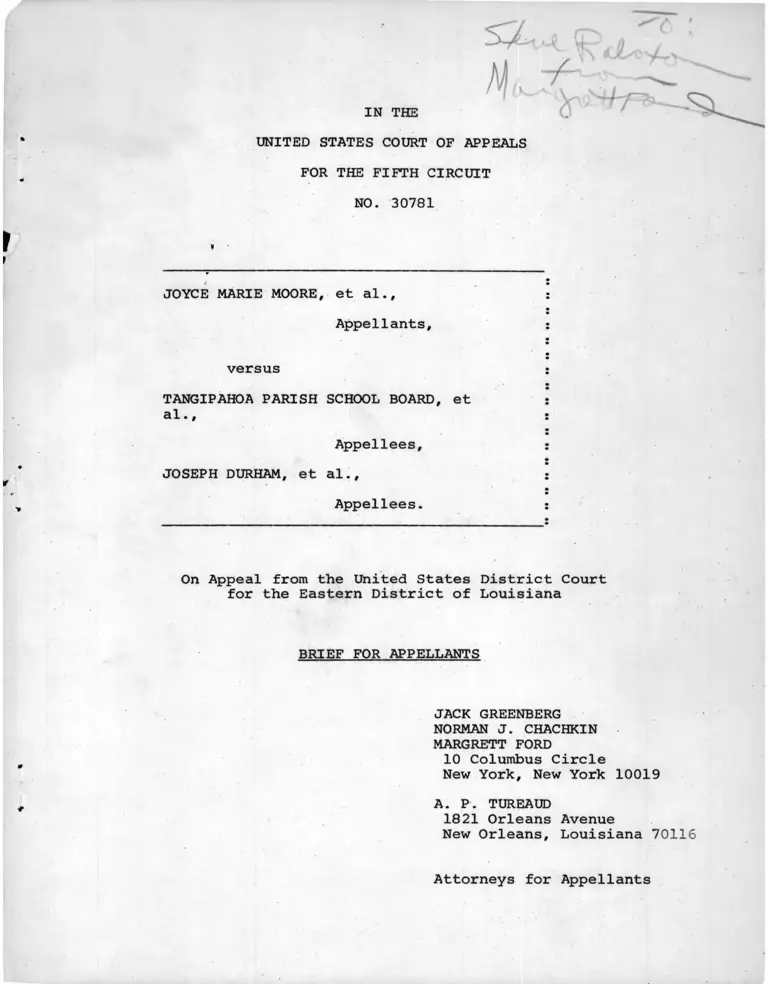

Moore v. Tangipahoa Parish School Board Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

February 10, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Moore v. Tangipahoa Parish School Board Brief for Appellants, 1971. 256981a2-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/53d3d683-cba2-4957-a4b2-d3da25fed662/moore-v-tangipahoa-parish-school-board-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 03, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

S2Ak

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 30781

JOYCE MARIE MOORE, et al.,

Appellants,

versus

TANGIPAHOA PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, et

al.,

Appellees,

JOSEPH DURHAM, et al.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Louisiana

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

JACK GREENBERG

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

MARGRETT FORD

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A. P. TUREAUD

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana 70116

Attorneys for Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.............................. i, ii

ISSUES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW....................... 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE............................. 2

STATEMENT OF FACTS................................ 9

ARGUMENT

I. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN DENYING PLAINTIFFS

MOTION :FOR FURTHER RELIEF WHERE THE BOARD

DEMOTED SEVEN (7) BLACK PRINCIPALS PRIOR TO

THE 1969-70 SCHOOL YEAR, WHILE HIRING SIX (6)

WHITE PRINCIPALS AND DEMOTING ONLY TWO (2)

WHITE PRINCIPALS AND WHERE SUCH DEMOTIONS

WERE MADE WITHOUT AN OBJECTIVE CRITERIA FOR

COMPARISON BETWEEN BLACK AND WHITE PRINCIPALS,

AND WHERE THE BOARD DEMOTED AND SUBSEQUENTLY

DISMISSED TWO (2) BLACK BAND DIRECTORS WHO

WERE EXPERIENCED IN THEIR FIELD WHILE HIRING

TWO (2) INEXPERIENCED WHITE BAND DIRECTORS

AND WHERE THE BOARD REFUSED TO EMPLOY QUA

LIFIED BLACK TEACHERS...................... 21

II. THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN APPROVING A

DESEGREGATION PLAN WHICH PROVIDED FOR

SEGREGATION OF SOME OF THE SCHOOLS AND

OR CLASSES BY SEX.......................... 27

CONCLUSION......................................... 28

TABLE OF CASES

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).... 4

Chambers v. Hendersonville City Board of

Education, 364 F. 2d 189 (4th Cir., 1966)..... 25, 26

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, 393 Fayette 2d 690 (5th Cir., 1968) 3,5

Dunn v. Livingston Parish School Board, No. 3197

(E.D. La. August 12, 1970)...................... 25

Franklin v. County School Board of Giles County,

360 F. 2d 325 (4th Cir., 1966).................. 26

Greene v. County Board of New Kent County, Virginia,

391 U.S. 430 (1968)............................. 2

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board, 417 F. 2d

801 (5th Cir., 1969)............................ 5,6

Hill v. Franklin County Board of Education, 390 F.

2d 583 (6th Cir., 1968)................... 25

Jackson v. Wheatley School District No. 28 of

St. Francis County, Arkansas, No. 19,952

(8th Cir., August 11, 1970)..................... 25

McBeth v. Board of Education of Devalls Bluff

School District No. 1 Ark., 300 F. Supp.

1270 (1969)..................................... 26

Moore v. Tangipahoa Parish School Board,

No. 15556 (E.D. La., July 2, 1969).............. 25

Rolfe v. County Board of Education of Lincoln

County, Tennessee, 391 F. 2d 77

(6th Cir., 1968)................................ 25, 27

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

District, 419 F. 2d 1211 (5th Cir., 1969)....... 21, 22

23, 25

Smith v. Concordia Parish School Board,

No. 11, 577 (W.D. La. 1970)...................... 25

Smith v. Morrilton School District, No. 32,

365 F. 2d 770 (8th Cir., 1966).................. 24, 25

Steward v. Stanton Independent School District,

374 F. 2d 774 (5th Cir., 1967).................. 25

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

380 F. 2d 285 (5th Cir., en banc 1967),

cert, denied sub, nom. Caddo Parish School Board v.

United States, 389 U.S. 840 (1967).............. 2, 25

Wall v. Stanley County Board of Education,

387 F. 2d 275 (1967)............................ 25, 27

l i

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 30781

JOYCE MARIE MOORE, et al. , :

Appellants, :

versus :

TANGIPAHOA PARISH SCHOOL BOARD, et :

al.,

Appellees, :

JOSEPH DURHAM, et al., •

Appellees. :

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Louisiana

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

TSSITES PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

Whether the District Court erred in denying plaintiffs

Motion for Further Relief where the Record showed that:

1. The Board demoted seven (7) Black principals prior to

the 1969-70 school year, while hiring six (6) white principals

and demoting only two (2) white principals, and where such

demotions were made without an objective criteria for compans..

between Black and white principals;

-2-

2. The Board demoted and subsequently dismissed two (2)

Black band directors who were experienced in the field while

hiring two inexperienced white band directors;

3. The Board refused to offer re—employment to one (1)

tenured Black teacher and two (2) non-tenured Black teachers;

one who had taught in the system for eight (8) years and one

who had taught for three (3) years, all because of racial

reasons; and

4. The desegregation plan approved by the court provided

for segregation of some schools by sex.

Statement of the Case

This case was filed on May 3, 1965, by Negro school

children seeking to desegregate the public schools of Tangipahoa

Parish, Louisiana. In June, 1965, an order was entered requiring

that desegregation be commenced pursuant to freedom of choice

in the fall of that year.

After the decision of this court in United States v. Jefferson

County Board of Education,i/ plaintiffs filed a Motion for Further

Relief, and on July 12, 1967, the court entered with slight

modification the Jefferson model decree.

Following the decision in Green v. County School Board of

Now Kent county. Virginia. 391 U.S. 430 (1968), plaintiffs filed

1/ 372 F. 2d 836, Affirmed with modifications_on rehearing en

banc 380 F. 2d 385 Cert, den., sub npiri_Caddo Parish School

Board v- United States. 389 U.S. 840 (1967).

-3-

a second motion for further relief alleging that Freedom of

choice had failed to effect a unitary system, and that other

methods promised a speedier conversion, and requesting that

the Board be directed to prepare, for implementation during

the 1968-69 school year, a plan incorporating such other

methods. Relying on Davis v. Board of School Commissioners

of Mobile County. 393 F. 2d 690 (5th Cir. 1968), the motion

also prayed that defendants be directed to conduct a detailed

survey of the system and to file with the court and the plain

tiffs a report thereof.

On June 26, 1968 the district court conducted a hearing

and on June 28th entered an order directing defendants: (1) to

conduct a survey of the extent of desegregation and file a

report thereon with the court and plaintiffs no later than

July 15th; and (2) to file, within 10 days thereafter, a new

plan for the assignment of pupils and teachers for the 1968-69

school year. A further hearing was scheduled for August 14,

1968.

On July 25, 1968 the Board filed a joint plan for students

and faculty. For the students the plan provided that all freedom

of choice forms be honored and that additional Negro students be

assigned to formerly white schools up to eight (8) percent of the

present white school. For the faculty it assigned 10% faculty

of the opposite race across the board with all schools having at

least one member of the opposite race.

-4-

to

Plaintiffs objected/the plan in that it failed to satisfy

Brown v. Board of Education and Green. A hearing was held on

August 14, 1968, on the Board's proposed plan and objections

thereto. Prior to the hearing's commencement, the Board filed

an amended plan that eliminated the feature which would have

assigned additional Negroes to white schools up to 8% of their

enrollment and that reverted to pure free choice. Similarly it

retracted, as to teachers, the 10% "across the board" it had

previously proposed.

On August 20, 1968, the district court filed an opinion

and order requiring assignments to be made based on the spring

choices but directing some supplemental procedures. The order

made clear, however, that the Board would have to devise changes

looking to the, 1969-70 school year.

A conference was held on October 10, 1968 with counsel for

all parties and on October 16, 1968, the Court entered an order

directing the defendants to submit to the court and serve upon

the plaintiffs:

1. A plan to be put into effect when classes commence

for the 1969-70 school year, calling for the assign-

ment of all students...by the adoption of geographic

attendance zones, or pairing of classes or both;

; *

!

2. A plan for the assignment of teachers, as well as

principals, assistant principals and supervisory

personnel on a non-discriminatory basis, based on

the plan for the assignment of students.

iI , '

■

-5-

Notice of appeal was filed by defendants on November 11,

1968. A stay pending appeal was granted April 2, 1969 and on

April 9th an order was entered adding this case for oral

argument on April 21, 1969.

This case was argued with some 38 other school cases,

Hall v. St. Helena Parish School Board. 417 F. 2d 801 (5th

Cir., 1969). This court required the submission and implemen

tation of desegregation plans other than "freedom of choice"

to convert the public schools of the respective districts into

unitary systems.

On June 7, 1969 the Board submitted a new desegregation

plan and on June 11, 1969 plaintiffs filed objections to the

new plan stating that the plan failed to comply with Davis v.

Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County, 393 F. 2d 1086

(5th Cir., 1969) .

A hearing was held on the new plan and the objections

thereto on June 17, 1969 and on July 2, 1969 the district court

entered an order which provided in part that:

A. All classroom assignments shall

be made on a racially non-discriminatory

basis and in such a manner that no class

is racially identifiable.

E. The principal of each of the schools

that will be closed shall be assigned

either as a principal to some other

school, or as an assistant principal

in a school that a member of the opposite

race is serving as principal, unless

it is determined in a particular instance

that this is not educationally feasible

-6-

for a valid reason not related to race.

Principals of all other schools shall

remain in charge of those schools unless

reassignment is required for some reason

other than race.

G. Principals, teachers, administrative

personnel, members of the professional

staff, athletic coaches, and other

persons in positions of responsibility

or authority shall not be assigned,

promoted, demoted or dismissed on a

racially discriminatory basis, nor in

any manner that makes a school racially

identifiable by the race of its staff.

Any personnel displaced as a result of

a school closing shall be assigned to

a similar position in some other school

on a racially non-discriminatory basis.

This shall not prevent the School Board

from failing to continue the employment

of any teacher who is not entitled to

tenure under state law, so long as its

decision is reached without racial dis

crimination of any kind.

P. With respect to Wards six and seven where

separate education for boys and girls has

been approved on a limited basis for 1969-

70 the school board shall report its plan

for the 1970-71 school year to the court,

opposing counsel, and the Educational

Resource Center on School Desegregation

no later than March 1, 1970.

The Board appealed from the District court's denial of

a Motion for New Trial from its July 2, 1969 order.

In spite of this court's order in Hall and the District

Court's order of July 2, 1969, the Board proceeded to coerce

and intimidate Black teachers into resigning their positions,

which resulted in plaintiffs filing a motion for an order

adjudging defendants in civil contempt of the district court's

order and for supplemental relief.

-7-

A hearing was held on the motion on August 22, 1969.

Although no formal order was signed the district court, in

making oral findings of fact and conclusions of law, denied

plaintiffs' motion for adjudication of contempt stating that

it could find no racial bias or discrimination. (Tr. Aug. 22,

1969; pp. 141-143).

On December 30, 1969, this court granted the defendants'

motion to dismiss the appeal taken from the District Court's

order of July 2, 1969.

Plaintiffs filed another motion for further relief on July

30, 1970, asking that the district court order the defendant

board to offer employment to Black teachers previously dismissed

by the Board; that the Board be required to reinstate a Black

principal, who had been principal for eight (8) years, and who

had been demoted to the level of classroom teacher and janitor;

and that the Board be ordered to eliminate segregated bus routes.

Hearings were had on plaintiffs' motion on August 11, 1970

and on August 24, 1970. The District Court entered an order

signed September 2, 1970, which granted relief as to the segre

gated classes and bus routes by race but denied relief as to

segregation of classes by sex and denied relief as to the re

instatement of the demoted Black principal and reinstatement

of the discharged Black teachers and reserved ruling on questions

relating to Black athletic coaches. On September 15, 1970,

plaintiffs appealed from the court’s decision of September 2,

1970.

-8-

On October 19, 1970, the District Court sua sp.onte ordered

another hearing on the matter on November 11, 1970 so that it

could take further evidence with respect to principals and

coaches referred to above. The hearing was held on November 11,

1970, with further evidence being presented.

On November 18, 1970, plaintiffs-appellants applied to this

court for an order holding the briefing schedule in abeyance

for 30 days because the District Court had not rendered a

decision on the issues placed before it on November 11, 1970.

This Court granted the motion to and including December 20,

1970.

Because the District Court still had not ruled on the

issues placed before it on November 11, 1970, plaintiffs found

it necessary to reguest another order to hold the briefing

schedule in abeyance for 30 days on December 17, 1970. Chief

Judge Brown granted the motion to and including January 10,

1971. On January 6, 1971, plaintiffs again requested that

the briefing schedule be held in abeyance because of the District

Court's failure to rule. Plaintiffs were given until February 1,

1971 to submit Briefs. Because plaintiffs had not received the

District Court's decision of January 25, 1971, plaintiffs on

January 28, 1971 filed an additional motion to hold the briefing

schedule in abeyance until 15 days after the District court's

decision. Plaintiffs received the District Court's decision of

January 25, 1971 on February 1, 1971 and filed a notice of appeal

and a motion to consolidate the two appeals on February 2, 1971.

-9-

The district court's decision of January 25, 1971, denied

plaintiffs' motion for further relief as to the principal,

assistant principals and band directors, but granted relief

as to coaches and assistant coaches.

This appeal and the previous appeal are from the district

court's failure to grant relief as to the demotion or firing of

principals, assistant principals, band directors, teachers, and

as to classrooms segregated by sex.

Statement of the Facts

Prior to the integration of schools there were thirteen (13)

Black principals and no assistant Black principals. There were

twenty (20) white principals and four (4) assistant white prin

cipals. After the integration of schools there are ten (10)

Black principals and two (2) assistant Black principals. There

are now twenty two (22) white principals and six (6) white

assistants.

Of the Black principals that remained seven (7) received

a demotion, with a cut in salary. Of this seven, four (4) were

reduced to the level of classroom teacher; one of whom was

demoted from high school principal to junior high school principal;

one of whom was demoted from high school principal to elementary

principal and one demoted from junior high school to elementary

school .-2/

_2/ Defendants answer to interrogatories of August, 1970.

-10-

Since the 1968-69 school year two (2) black band directors

were reduced to assistant band directors and subsequently

released by the defendant school board.

Only two (2) white assistant principals were reduced to

the level of classroom teacher and no white band directors

were dismissed, demoted or reduced to the level of classroom

teacher.

There were numerous Black teachers dismissed, prior to

the 1969-70 and 1970-71 school years. At the hearing before

the district court on August 22, 1969, one of the issues placed

before the court was that of the dismissal of Black teachers

and the Board's practice of intimidating Black teachers into

resigning. The court found that there was no racial bias or

discrimination on the part of the School Board against these

Black teachers.-2/ At the August 11, 1970 hearing, plaintiffs

again attempted to raise the issue with reference to the 1969

discriminatory dismissal and/or intimidation of these Black

teachers because there was some question in the mind of counsel

for plaintiffs^/as to whether or not the court had ordered the

Board to offer employment to some of these dismissed teachers .-̂ /

3/ Tr. August 22, 1969, pp. 141-143.

4/ Atty. A. P. Tureaud. As a result of this misunderstanding,

the court ordered a transcript of the August 22, 1961 hearing.

However, the Transcript of August 22, 1969 hearing did not

indicate that the court had ordered the Board to offer

employment to these teachers.

5/ Tr. August 11, 1970, pp. 25-29.

-11-

The Court refused to entertain the question of the dismissal

of these teachers in that it had heard testimony as to them m

August of 1969. The court did entertain testimony as to three

teachers that were released after the 1969-70 school term, they

were Mrs. Gloria Duplessis, Mrs. Mary Walker and Mr. Joseph

Richardson. The two black band directors that were released

were Mr. Edward Duplessis and Mr. Dennis Epps.

As previously stated, prior to the integration of schools

there were thirteen (13) Black principals. As of the 1969-70

school year, seven (7) of these Black principals had been demote^

with a reduction in salary.

Prior to the District Court's order of July 2, 1969, the

defendant board had maintained three (3) schools segregated by

sex; two (2) elementary and one (1) jr. high school. After

the court ordered integration plan, spearation by sex was allowed

to extend to the high school level in some wards.

The Black principal most severly affected by the discrimina

tory practices of the Board was Mr. Fred McCoy, who had been an

elementary school principal of a Black school for eight (8) years,

but was demoted to the level of classroom teacher in July, 1969.

The Board attempted tojustify demoting McCoy by stating that

that he was not certified as a principal under state certification

standards. McCoy, however, testified without contradiction that

there was an agreement between him and the former superintendent,

Dewitt Sauls, that he would be appointed principal if he would

accumulate six hours per year towards his Master's in Administratio

-12-

the one certification requirement he lacked - McCoy testified

that he did attend graduate school at night, on Saturdays and

during the summer in order to live up to his part of the agree

ment. He stated that he has acquired 20 hours, of the 36

6/required, towards Tiis Masters in Administration.

McCoy also testified, without contradiction, that he had

not completed his Masters because he was required to spend five

(5) hours per day at his school during the summer vacation months,

and that he had asked the superintendent to relieve him of his

summer responsibilities so that he could attend school,—^ but

that he was required to sit at the school and supervise the

j anitor.

Marion Hendry, who is the Supervisor of Instruction, but

who has worked in the capacity of Supervisor of Personnel for the

past year and a half, testified that when he got the job of

Supervisor in 1967, the system had quite a few principals th-

did not hold a Masters degree in the Negro schools. The overall

situation was that most of the white principals had the Masters

degree and that a good number of the Negro principals did not.

However he went on to testify as follows:

Q. Now, if you had a vacancy at this time, based on your

knowledgeof Mr. McCoy, would you hire him as a prin

cipal?

A. No.

Q . Why not?

6/ Tr. Aug. 11, 1970, pp. 105-108; 126-130.

7/ Tr. August 11, 1970, pp. 128-129.

-13-

A. I just would feel like that he w a s -- he was not

certified where we would have people holding a degree,

I feel like would have been certified.

Q. Do you think he would handle the disciplinary situation

in the schools today as a principal?

A. Well, of course, that would be my belief, in some of

the larger schools, I'd have to say he couldn't handle

it.

Q. Do you think he could handle it in the smaller schools?

A. Depends on the circumstances that would arise from it,

Mr. Simpson.

Q. Did he have any disciplinary problems at Midway after

you became supervisor

A. Not any that I can remember, no.-8/

Accordingly, it was admitted that McCoy did not have any

disciplinary problems while he was principal at Midway Elementary

School.

Indeed, after testifying that he did not believe that McCoy

was capable of handling the situation at a large school, Hendry

was asked (Tr. August 11, 1970, p. 70):

Q. Mr. Hendry, you indicated that you didn't think Mr.

McCoy was capable of handling a larger high school?

A. I did.

Q. Larger school?

A. I did.

Q. Do you have any Black principals of large high schools

in the parish?

A. No we do not.

Q. Do you have any Black principals at large schools?

A. No, sir.

8/ Tr. August 11, 1970, pp. 76-77.

-14-

McCoy testified, without contradiction that there were

six (6) vacancies for principals in the parish since his demotion

in July 1969 and that none of his positions were offered to him

in spite of the fact that he had eight (8) years experience as

a principal, and that all six vacancies were filled by members

of the white race.-3/ McCoy testified that he suffered a cut in

salary in the amount of $3,029.80 annually.

In addition to the demotion of McCoy to the level of class

room teacher, the Board demoted the following Black principals

in the following way:

1. Robert Warford from Assistant Principal to classroom

teacher, with a reduction in salary of $116.67 per

month;

2. Bernice Smith from teaching elementary principal to

classroom teacher with a reduction in salary of $57.15

per month;

3. Nelson Cyprian from teaching elementary principal to

classroom teacher with a reduction in salary of $65.73

per month;

4. Manley Younglbood from High School principal to Jr. hith

school principal;

5. C. B. Temple from High School principal to elementary

principal with reduction in salary of $47.39 per month;

and

6. Joe Brumfield from Jr. High School principal to elementary

principal with a reduction in salary of $27.28 per month._

9/ Tr. August 11, 1970, p. 121-122

10/ Tr. August 11, 1970, p. 120

11/ Answer to interrogatories by defendants in August, 1970.

-15-

While the Board has demoted seven Black principals and

assistant principals, it has demoted only two (2) white assista

principals, one with only a reduction of $7.40 per month in

salary.

When integration took place, two Black band directors at

previously Black schools, Edward Duplessis and Dennis Epps,

were demoted to assistant band directors and subsequently were

dismissed by the Board. Prior to dismissal Duplessis suffered

a cut in monthly salary of $49.07 and Epps suffered a cut in

salary of $50.00 per month. At the same time, no white band

directors, on the other hand, were demoted or dismissed,

resulting in there being no Black band directors in the system.

Indeed, after the demotion of Epps and Duplessis the Board

hired a band director and an assistant band director, both of

whom were white, without offering the positions to Epps or

Duplessis.

Hendry, Supervisor of Instruction, succinctly stated

that there was no reason why the job was not offered to

Epps (Tr. August 24, 1970, pp. 16-17):

Q. Have you recently hired a new band director

for the parish?

A. Yes, we hired a band director.

Q. What school was he assigned?

12/A. Kentwood High School.—

12/ Kentwood was a formerly all white school.

-16-

Q. How long has he been in the Tangipahoa Parish

School System?

A. This is his first year.

Q. The first year in the system?

A . Right.

Q. Therefore, he has not been a coach, I mean a band

director in the parish prior to this?

A. No.

Q. Did you offer this job to Mr. Epps?

A . No.

Q. Did you — is there any particular reasons why you

did not offer him a job as band director?

A . No.

Hendry also testified that when the assistant band director

was hired, the position was not offered to Epps. (Tr. August 24,

1970, p. 17). There was also testimony to the effect that Epps

had passed the National Teachers Exam, whereas the newly hired

band director had not (Tr. Aug. 24, 1970, p. 36).

Mr. Edward Duplessis did not testify at the hearing nor

was his demotion discussed, but the board in cross-examining

Mr. Epps and on direct to Mr. C. B. Temple, (his former

principal at the all Black high school) attempted to prove

that Mr. Epps was responsible for a student demonstration at

the s c h o o l A t no time was it stated that Epps led the

13/ Tr. August 24, 1970, pp. 149-150; 153-154.

students in the demonstration, and as a matter of fact

meetings took place between Mr. Temple, Mr. Hendry and Mr.

Epps and nothing resulted from these meetings. Indeed,

Epps' former principal (C. B. Temple) stated that after

nothing was done about their meetings, he just forgot about

it'lA/ Thus, not only was there nothing to show that Epps

was dismissed or demoted as a result of the student demonstra-

tion, but he was transferred to another school at the end of

that school year and was allowed to teach for 1\ years after

the incident occurred. The Board made no attempts to prove

that Epps' performance was unsatisfactory for the 1969-70

school year.

There were numerous Black teachers dismissed. However,

only two testified at the August 24, 1970 hearing. In addition,

a school board official was cross-examined about a third one.

Mrs. Gloria Duplessis testified that she had taught in

the school system for eight years, seven of these years in

Black schools, including Dillon High School, and one in an

integrated, former all-white school, and was dismissed after

the one year at the former all-white school. She testified

that for the first four months at the former all-white school,

Chesbrough, she had absolutely no duties to perform and that

14/ Tr. August 24, 1970, p. 153.

-18-

at her other assignment. Spring Creek, she had students sent

to her class (rather than having been brought by the classroom

teacher) in 30 minute intervals. Mrs. Duplessis further

testified that at no time was she observed by a supervisor at

these two schools.iS/firs. Duplessis explained that for dis-

plinary purposes it would have been better for her if the

classroom teacher would have accompanied the students.

The Board attempted to prove that Mrs. Duplessis' per

formance at Dillon was unsatisfactory. However, Mr. Temple,

the former principal at the former Dillon High School testi

fied that he was quite pleased with Mrs. Duplessis' work,

but that he had on occasions been displeased because of her

absence due to illness. Here again, the Board did not put

Mrs. Duplessis' principal for the 1969-70 school year on the

stand to testify as to her performance.-1̂ /

Very much like Mr. McCoy, Mrs. Duplessis had an agree

ment with Mr. Dewitt Sauls, the former superintendent, that

she would be allowed to teach in the parish with a temporary

teacher's certificate while she worked for her B.A. degree.

This she did, and she testified that she only needed 12 hours

for her B.A. degree 12/

15/ Tr. August 24, 1970, pp. 98-107.

16/ Tr. August 24, 1970, pp. 150-152; 154-155

17/ Tr. August 24, 1970, pp. 101-102.

-19-

The Board also released Mrs. Mary Walker, who had

taught in the system for three years; two years at the former

Dillon High School, formerly an all Black school, and seven

months at Ponchatoula High School (seven months due to

maternity leave) .A^The principal at Ponchatoula, formerly

an all white school, testified that Mrs. Walker was incompetent

because she did not keep her students quiet in her study

period, but also testified that he had never sat in on any

of her academic classes in order to determine her competency

in those classes .A^/There were no complaints about Mrs. Walker

for the two years while she was assigned to the Black Dillon

High School.

On cross-examination a school board official testified

concerning the third Black teacher, Mr. Joseph Richardson to

the effect that he was required to take the National Teachers

examination because he had taught one year in the system prior

to entering the military service for two years and had resume

his teaching position in the parish upon his release.AO/rhis

meant that at that time he entered his fourth year of credit

for teaching. Board officials had previously testified that

teachers who had acquired tenure were not required to take the

exam. However, in Mr. Richardson's case he was required to

take the exam because he had not acquired tenure although given

18/ Tr. August 24, 1970, pp. 94-97.

19/ Tr. August 24, 1970, pp. 136-143

20/ Tr. August 24, 1970, pp. 21-23.

-20-

credit for time served in the military services.

Evidence demonstrated that the Board made no pretext

of setting up objective criteria for demoting principals,

band directors and dismissing teachers.-^

21/ Tr. August 24, 1970, pp. 9-10

-21-

Argument

I

THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN DENYING PLAINTIFFS'

MOTION FOR FURTHER RELIEF WHERE THE BOARD DEMOTED

SEVEN (7) BLACK PRINCIPALS PRIOR TO THE 1969-70

SCHOOL YEAR, WHILE HIRING SIX (6) WHITE PRINCIPALS

AND DEMOTING ONLY TWO (2) WHITE PRINCIPALS AND

WHERE SUCH DEMOTIONS WERE MADE WITHOUT AN OBJECTIVE

CRITERIA FOR COMPARISON BETWEEN BLACK AND WHITE

PRINCIPALS, AND WHERE THE BOARD DEMOTED AND

SUBSEQUENTLY DISMISSED TWO (2) BLACK BAND DIRECTORS

WHO WERE EXPERIENCED IN THEIR FIELD WHILE HIRING

TWO (2) INEXPERIENCED WHITE BAND DIRECTORS AND

WHERE THE BOARD REFUSED TO EMPLOY QUALIFIED BLACK

TEACHERS .

The court below, in its order of July 2, 1969, tracked

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District, 419

F.2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1969), and ordered:

Sec. I (E). The principal of each of the schools

that will be closed shall be assigned either as a

principal to some other school, or as an assistant

principal in a school that a member of the opposite

race is serving as principal, unless it is deter

mined in a particular instance that this is not

educationally feasible for a valid reason not

related to race....

Sec. I (G). Principals, teachers, administrative

personnel, members of the professional staff,

athletic coaches, and other persons in positions

of responsibility or authority shall not be

assigned, promoted, demoted or dismissed on a

racially discriminatory basis, nor in any manner

that makes a school racially identifiable by the

race of its staff. Any personnel displaced as a

result of a school closing shall be assigned to

a similar position in some other school on a

racially nondiscriminatory basis. This shall not

prevent the school board from failing to continue

the employment of any teacher who is not entitled

to tenure under state law, so long as its decision

is reached without racial discrimination of any

kind.

-22-

Contrary to the Fifth circuit's order in Singleton,

supra, and this Court's order of July 2, 1969, the School Board

proceeded to demote and dismiss Black principals and Black

teachers. In less than ten days of this Court's order, the

Board reduced Fred McCoy, Jr., former principal at all-Black

Midway Elementary School, to the level of classroom teacher.

The Board’s justification for this demotion was that it

did not feel that Mr. McCoy was capable of handling the

administration of an integrated school, while at the same time

admitting that there were no Black principals at any of the

high schools in the parish. It was also admitted that new

white principals have been hired by the Board since the demotion

of Mr. McCoy and that Mr. McCoy was not offered a position

as principal although he has had experience as a principal

for eight years and the persons that were hired had far less

experience.

The Board attempted to justify its position by stating

that Mr. McCoy was not certified as a principal, but Mr. McCoy

testified without contradiction that there was an agreement

between him and the former superintendent, Dewitt Sauls, that

he would be appointed principal if he would accumulate six

hours per year towards his Masters in Administration. Mr. McCoy

testified that he did attend school at night, on Saturdays

and during the summer in order to live up to his part of

the agreement. He stated that he has acquired 20 hours

towards his Masters in Administration.

-23-

One of the Singleton requirements in the case of demotions

is that no vacancy may be filled through recruitment of a

person of a race, color, or national origin different from

that of the individual dismissed or demoted, until each

displaced staff member who is qualified has had an opportunity

to fill the vacancy and has failed to accept an offer to do so.

Clearly, there have been vacancies in principalships and

assistant principalships since McCoy was demoted, most of which

have been filled by whites.

It is also clear that as long as Mr. McCoy was qualified

to take the position, no white persons could be hired even if

they were somewhat more qualified than Mr. McCoy. That

Mr. McCoy was qualified to fill these openings is evident

from the fact that he had been appointed by the school district

to the position of principal for the previous eight years.

In an attempt to show some concrete standard on which

it based its demotions, the school board has pointed to the

fact that Mr. McCoy has not yet attained his Master's degree.

However, this is a classic instance of using standards ex

post facto to justify an otherwise inexplicable action. At

no time prior to his demotion was Mr. McCoy informed a

Master's degree was a necessary requirement for his position.

In fact, at the time of his demotion, numerous principals

throughout the parish system possessed only a Bachelor's

degree (Aug. 24 Transcript p. 44, Aug. 11 Transcript p. 76,

Record Chart showing degrees).

-25-

In view of the court-ordered plan for the Tangipahoa

Parish School system, the school district was obligated to

appraise the demoted principals and teachers qualifications

on a nonracial basis. Moore v. Tangipahoa Parish School Board,

No. 15556 (E.D. La., July 2, 1969); Singleton v._Jackson

Municipal Separate School District, 419 F.2d 1211, 1217, 1218

(5th Cir., en banc, 1969); United States v. Jefferson County

Board of Education, 380 F.2d 385, 394 (5th Cir., en banc, 1967);

Steward v. Stanton Independent School District, 375 F.2d 774

(5th Cir. 1967) (per curiam); Chambers v. Hendersonville City

Board of Education, 364 F.2d 189 (4th Cir. 1966); Rolfe__v.

County Board of Education of Lincoln County, Tennessee, 391

F.2d 77 (6th Cir. 1968); Smith v. Morrilton School District

No. 32, 365 F.2d 770 (8th Cir. 1966); Smith v. Concordia

Parish School Board, No. 11,577 (W.D. La. 1970), and Dunn v.

Livingston Parish School Board, No. 3197 (E.D. La., August 12,

1970).

Moreover, when it became necessary to discharge or demote

principals or teachers because of the integration of schools,

the Board was required to compare their qualifications with all

of the teachers in the system and not just at their school.

Hill v. Franklin County Board of Education, 390 F.2d 583

(6th Cir. 1968); Wall v. Stanley County Board of Education,

378 F.2d 275 (1967); Jackson v. Wheatley School District No.---

of St. Francis County, Arkansas, No. 19,952 (8th Cir., Aug. 11,

1970); Rolfe v. County Board of Education of Lincoln County,— Term

-24-

Further, this is the only criteria used by the Board.

It neglects other relevant factors that should have been

considered, such as Mr. McCoy’s eight years of experience

and his fine record devoid of disciplinary problems (Aug. 11

Transcript p. 77). See Smith v. Morrilton School District

NO. 32, 365 F.2d 770 (8th Cir. 1966).

Finally, by requiring a Master's degree of all

principals, the school system is penalizing Black personnel

for the Board's own prior unconstitutional segregated school

policy. under the previous dual system, Black principals

were not required to hold a Master's degree while in general

white principals were (Aug. 11, 1970, Tr. 76-77). By now

requiring all Black principals to hold a Master's degree without

allowing a reasonable time for them to meet the new standard,

the Board effectively discriminates against Black personnel.

indeed the Board stated that "there can be no question

but what the educational background of the Negro teachers

and principal; their ability to control classroom and school

situation which arise is not as good as a class, as the white

teachers."^ However, the District Court in its September 2,

1970 order found no pattern of racial discrimination by the

Board against Black teachers.

22/ Memorandum Brief submitted to District Court by Defendants

on October 8, 1970, p. 1-

-26-

391 F.2d 77 (1968); McBeth v. Board of Education of Devalls

Bluff School District No. 1, Ark., 300 F. Supp. 1270 (1969),

and Franklin v. County School Board of Giles County, 360 F.2d

325 (4th Cir. 1966). Thus, the court in Chambers v.

Hendersonville City Board of Education, supra, stated that

'•Negro school teachers, as a class, were entitled to an order

requiring the school board, which decreased number of positions

open to Negro teachers from 24 to 8, to set up definite objective

standards for employment and retention of teachers and to apply

them to all teachers alike in a manner compatible with require

ments of due process and equal protection.

in this case the Tangipahoa Parish School Board has made

no pretext of setting up an objective criteria for demoting

principals, band directors and dismissing teachers. Indeed

the Board official testified that the Board did not feel that

the demoted principal was capable of handling an integrated

school. Obviously no other criteria was used in demoting

Black principals, since only two white assistant principals

were demoted while no white principal was demoted. As a matter

of fact, the Board made no effort to prove that they compared

the qualifications of the demoted and dismissed Black teachers

and principals with others in the system and found them inferior

prior to their demotion or dismissal.

The Board's actions in demoting Black principals and

band directors and dismissing Black teachers while retaining

-27-

whites would lead one to believe that these Black teachers

and principals were hired to teach only in Black schools and

not in white schools. Employment of Black teachers, not as

teachers in the entire school system, but as teachers in Black

schools only is repugnant to the Fourteenth Amendment. Wall

v, Stanley County Board of Education, 378 F.2d 275 (1967).

At no time prior to the demotions did the Defendant-

Appellees develop or require the development of non-racial

objective criteria to be used in selecting the staff members

to be demoted, and no objective criteria were used in fact

prior to the demotions. Where there is a history of racial

discrimination in the school system the burden of showing non

discrimination in relation to teacher employment is on the School

Board, Rolfe v. County Board of Education of Lincoln County,

Tennessee, 391 F.2d 77 (6th Cir. 1968).

II

THE DISTRICT COURT ERRED IN APPROVING

A DESEGREGATION PLAN WHICH PROVIDED FOR

SEGREGATION OF SOME OF THE SCHOOLS AND/

OR CLASSES BY SEX.

In its September 2, 1970 order the District Court

allowed the School Board to continue segregating some of its

schools and classes by sex, stating that at present there is

no evidence of a pattern of racial discrimination resulting

from this sex separation.

Prior to the desegregation order which integrated the

schools, two elementary schools and one junior high school

-28-

were segregated by sex. However, after the court ordered

the schools desegregated, separation by sex was extended to

the high school level. This would leave one to believe that

such extension was for the purpose of separating Black boys

from white girls and white boys from Black girls, and such

action violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons stated, the decree of the District

Court as far as it denies relief to Black principals, teachers,

band directors and segregation of students by sex should be

reversed by this Court.

Respectfully submitted,

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

MARGRETT FORD

10 Columbus circle

New York, New York 10019

A. P. TUREAUD

1821 Orleans Ave.

New Orleans, Louisiana

Attorneys for Appellants

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that I have this 10th day of February,

1971, mailed a copy of the foregoing Brief for Appellants

-29-

to counsel for appellees and intervenors by placing same in

the United States mail, postage prepaid, addressed as follows

Joseph H. Simpson, Esq-

Assistant District Attorney

21st Judicial District

Amite, Louisiana 70422

John D. Kopfler, Esq.

P.0. Box 1209

Hammond, Louisiana.