McCleskey v. Kemp Brief for Respondent

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McCleskey v. Kemp Brief for Respondent, 1985. e5bb5472-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/53ebbd52-ec9b-4cb3-838c-472a025983bf/mccleskey-v-kemp-brief-for-respondent. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

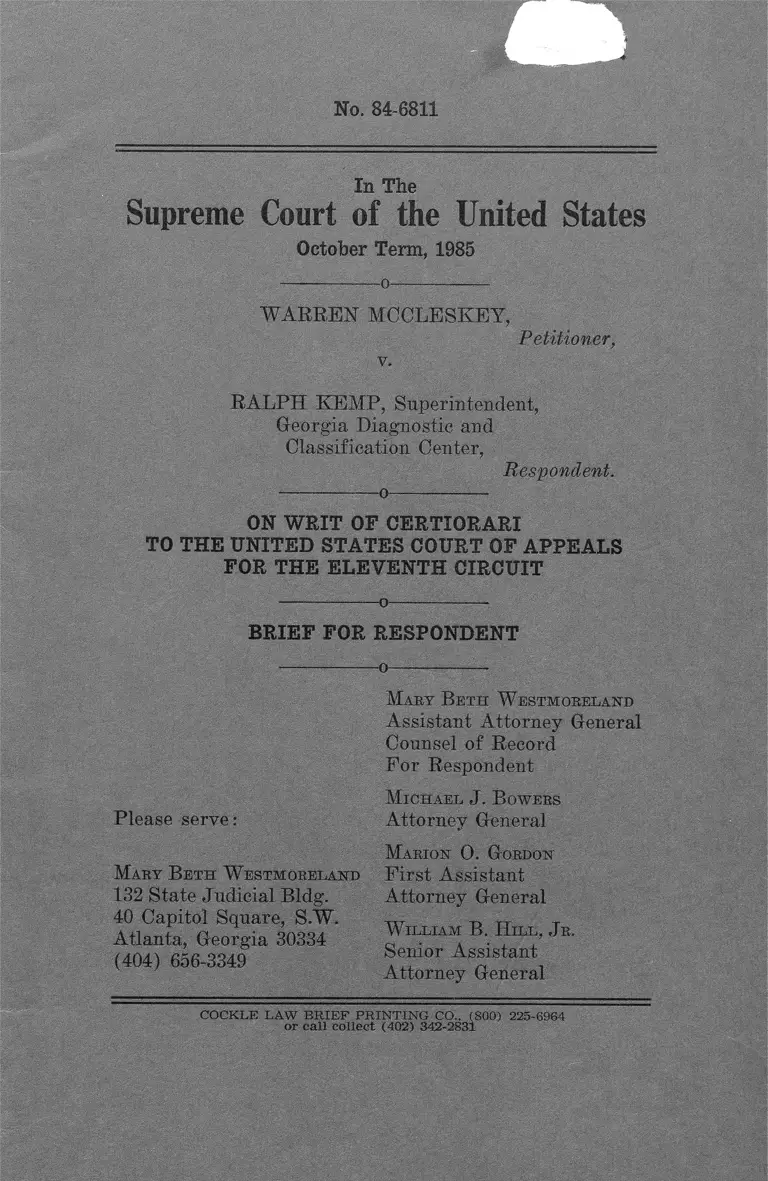

In The

Supreme Court o f the United States

October Term, 1985

------------------------------------- o — — — —

WARREN MCCLESKEY,

v.

Petitioner,

RALPH KEMP, Superintendent,

Georgia Diagnostic and

Classification Center,

Respondent.

o

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

------------------------------ o — — ------------

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT

Please serve:

Mart B eth W estmoreland

132 State Judicial Bldg.

40 Capitol Square, S.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30334

(404) 656-3349

•o-—-------------

Mary B eth W estmoreland

Assistant Attorney General

Counsel of Record

For Respondent

Michael J. B owers

Attorney General

Marion 0 . Gordon

First Assistant

Attorney General

W illiam B. H ill, Jr.

Senior Assistant

Attorney General

COCKLE LAW BRIEF PRINTING CO., (800) 225-6964

or call collect (402) 342-2831

1

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1.

Is the statistical analysis which was presented to the

district court inadequate to prove a constitutional viola

tion, both as a matter of fact and as a matter of law?

2.

Are the arbitrariness and capriciousness concerns of

Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972), removed when a

state properly follows a constitutional sentencing proce

dure?

3.

In order to establish a constitutional violation based

on allegations of discrimination, must a petitioner prove

intentional and purposeful discrimination?

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ......................................... i

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ................................... 1

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ............................ 5

ARGUMENT

I. STATISTICAL ANALYSES ARE INADE

QUATE AS A MATTER OF FACT AND LAW

TO PROVE DISCRIMINATION UNDER THE

FACTS OF THE INSTANT CASE..................... 7

II. THE STATISTICAL ANALYSES IN THE IN

STANT CASE ARE INSUFFICIENT TO

PROVE RACIAL DISCRIMINATION............... 16

III. THE ARBITRARINESS AND CAPRICIOUS

NESS CONCERNS OF FURMAN V. GEOR

GIA, 408 U.S. 238 (1972), ARE REMOVED

WHEN A STATE PROPERLY FOLLOWS A

CONSTITUTIONAL SENTENCING PROCE

DURE......................................................................... 23

TV. PROOF OF DISCRIMINATORY INTENT IS

REQUIRED TO ESTABLISH AN EQUAL

PROTECTION VIOLATION................................ 31

CONCLUSION .................................................................. 37

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page(s)

Cases Cited:

Bazemore v. Friday, — U.S. —, 106 S.Ct. 3000

(1986) ................................................ ...........................10,20

Britton v. Rogers, 631 F,2d 572 (5th Cir. 1980),

cert, denied, 451 U.S. 939 (1981) ............................... 8

Caldwell v. Mississippi, 472 U.S. —, 105 S.Ct. 2633

(1985) ........................................................................... 13

California v. Ramos, 463 U.S. 992 (1983) ...................... 28

Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482 (1977) .................. 32

Eastland v. Tennessee Valley Authority, 704 F.2d

613 (11th Cir. 1983) ...... 11

Eddings v. Oklahoma, 455 U.S. 104 (1982) .................. 13

Enmund v. Florida, 458 U.S. 782 (1982) ...................... 27

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v.

Datapoint Corporation, 570 F.2d 1264 (5th Cir.

1978) .............. ........... ..................................................... 10

Estelle v. Gamble, 429 U.S. 97 (1976) ............................ 24

Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972) ...........8, 24, 25,27,

28, 29, 30

Godfrey v. Georgia, 446 U.S. 420 (1980) ...................... 27

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960) ....... .......33, 35

Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153 (1976) .........25, 26, 27, 28, 29

Ingraham v. Wright, 430 U.S. 651 (1977) .................... 24

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977) ................ ,....................... 9

Johnson v. Uncle Ben’s Inc., 628 F.2d 419 (5th Cir.

1980) ............................................................................... 11

Lockett v. Ohio, 438 U.S. 586 (1978) ......................13, 26, 27

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page(s)

Louisiana ex rel. Francis v. Reswebef, 329 II.S.

459, rlfmg. denied, 330 U.S. 853 (1947) ...................... 24

Maxwell v. Bishop, 398 F.2d 138 (8th Cir. 1968),

remanded on other grounds, 398 U.S. 262 (1970) ..... 12

Mayor of Philadelphia v. Educational Equality

League, 415 U.S. 605 (1974) ....................................... 8

McCleskey v. Kemp, 753 F.2d 877 (11th Cir. 1985)

(en banc) ....................................................................... 4

McCleskey v. Zant, 580 F.Supp. 338 (N.D.Ga. 1984).....1, 2,

3, 4,17,18, 20, 23

McCorquodale v. Balkcom, 525 F.Supp. 408 (N.D.

Ga. 1981), affirmed, 721 F.2d 1493 (11th Cir. 1983)... 13

McGautha v. California, 402 U.S. 183 (1971) .............. 12

Oyler v. Boles, 368 U.S. 448 (1962) .......................... 31

Personnel Administrator of Massachusetts v.

Feeney, 442 U.S. 256 (1979) ....................................... 33

Proffitt v. Florida, 428 U.S. 242 (1976) .......... ............ 26

Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273 (1982) ......... 17

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982) ............................ 33

Shaw v. Martin, 733 F.2d 304 (4th Cir. 1984) .............. 13

Smith v. Balkcom, 660 F.2d 584 (5th Cir. 1981), on

rehearing, 671 F.2d 858 (5th Cir. Unit B, 1982) ....... 13

Spinkellink v. Waimvright, 578 F.2d 582 (5th Cir.

1978) ............................................................................... 13

Stephens v. Kemp, — U.S. —, 104 S.Ct. 562 (1983) ... 28

Prop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86 (1958) ..............................14,24

Turner v. Murray, — U.S. —, 106 S.Ct. 1683 (1986) ... 14

United States v. Ironworkers Local 86, 443 F.2d

544 (9th Cir. 1971) ............... ....................................... 10

V

United States v. United States Gypsum- Co., 333

U.S. 364 (1948)__________________________________ 17

Valentino v. United States Postal Service, 674

F.2d 56 (D.C.Cir. 1982) .............. ............................... 11

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Hous

ing Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977)...........32, 33

Wade v. Mississippi Cooperative Extension Ser

vice, 528 F.2d 508 (5th Cir. 1976) .............................. 10

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976).................. 31, 32

Wayte v. United States, — U.S. —, 105 S.Ct. 1524

(1985) ............................................................................. 33

Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545 (1967) ........................ 31

Wither son v. Utah, 99 U.S. 130 (1878) .......................... 23

Wilkins v. University of Houston, 654 F.2d 388

(5th Cir. Unit A 1981) ................................................ 11

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510 (1968) ................ 14

Woodson v. North Carolina, 428 U.S. 280 (1976) ......... 26

Tick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886) .................... 31, 33

Other A uthorities :

Baldus & Cole, A Comparison of the Work of Thor-

sten Sellin and Isaac Ehrlich on the Deterrent

Effect of Capital Punishment, 85 Yale L. J. 170

(1975) ............................................................................ 15

Fisher, Multiple Regression in Legal Proceedings,

80 Colnm. L.Rev. 702 (1980) ....................................15, 20

A. Goldberger, Topics in Regression Analysis (1968) 15

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page(s)

VI

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page(s)

McCabe, The Interpretation of Regression Analy

sis Results in Sex and Race Discrimination

Problems, 34 Amer. Stat. 212 (1980) ......................... 16

Smith and Abram, Quantitative Analysis and Proof

of Employment Discrimination, 1981 U.I11. L.Rev.

33 (1981) ....................................................................... 15

G. Wesolowsky, Multiple Regression Analysis of

Variance (1976) ............................................................ 15

No. 84-6811

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1985

WARREN MCCLESKEY,

Petitioner,

RALPH KEMP, Superintendent,

Georgia Diagnostic and

Classification Center,

Respondent.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT

— — ------------ — o ----------------------------------

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

In addition to the statement of the case set forth by

the Petitioner, Respondent submits the following regard

ing the district court and circuit court proceedings:

Two different studies were conducted on the criminal

justice system in Georgia by Professors Baldus and Wood-

worth, that is, the Procedural Reform Study and the

Charging and Sentencing Study. See McCleskey v. Zant,

580 E.Supp. 338, 353 (N.D.Ga. 1984). The Petitioner pre

sented his case primarily through the testimony of Pro

fessor David C. Baldus and Dr. George Woodworth. Peti

tioner also presented testimony from Edward Gates as

1

2

well as an official from the State Board of Pardons and

Paroles. The state presented testimony from two expert

statisticians, Dr. Joseph Katz and Dr. Roger Buford.

The district court made the following specific factual

findings regarding the trustworthiness of the data base:

[T]he court is of the opinion that the data base has

substantial flaws and that the petitioner has failed to

establish by a preponderance of the evidence that it

is essentially trustworthy. As demonstrated above,

there are errors in coding the questionnaire for the

case sub judice. This fact alone will invalidate several

important premises of petitioner’s experts. Further,

there are large numbers of aggravating and mitigat

ing circumstances data about which is unknown. Also,

the researchers are without knowledge concerning the

decision made by prosecutors to advance cases to a

penalty trial in a significant number of instances. The

court’s purpose here is not to reiterate the deficien

cies but to mention several of its concerns. It is a

major premise of a statistical case that the data base

numerically mirrors reality. If it does not in substan

tial degree mirror reality, any inferences empirically

arrived at are untrustworthy.

McGleskey v. Zant, supra, 580 F.Supp. at 360 (emphasis

in original). (J.A. 144-5).

The district court found as fact that “ none of the

models utilised by the petitioner’s experts were sufficient

ly predictive to support an inference of discrimination.”

McCleskey v. Zant, supra at 361. (J.A. 149).

The district court also found problems in the data due

to the presence of multicollinearity. The district court

noted that a significant fact in the instant case is that

white victim cases tend to be more aggravated, that is

correlated with aggravating factors, while black victim

3

eases tend to be more mitigated, that is correlated with

mitigating factors. Every expert who testified, with the

exception of I)r. Berk, agreed that there was substantial

multicollinearity in the data. The district court found,

“ The presence of multi-colinearity substantially dimin

ishes the weight to be accorded to the circumstantial statis

tical evidence of racial d isp a rityM cC leskey v. Zant,

supra at 364. (J.A. 153). The court then found Petitioner

had failed to establish a prima facie case based either on

race of victim or race of defendant. Id.

Additionally, the district court found “ that any racial

variable is not determinant of tvho is going to receive the

death penalty, and, further, the court agrees that there is

no support for a proposition that race has any effect in

any single case.” McCleskey v. Zant, supra at 366 (empha

sis in original). (J.A. 157). “ The best models which

Baldus was able to devise which account to any significant

degree for the major non-racial variables, including

strength of the evidence, produce no statistically signifi

cant evidence that race plays a part in either of those de

cisions [by the prosecutor and jury] in the State of

Georgia.’ ’ McCleskey v. Zant, at 368 (emphasis in origi

nal). (J .A .159).

Finally, the district court found that the analyses did

not “ compare identical cases, and the method is incapable

of saying whether or not any factor had. a role in the de

cision to impose the death penalty in any particular case.”

McCleskey v. Zant at 372 (emphasis in original). (J.A.

168). “ To the extent that McCleskey contends that he was

denied either due process or equal protection of the law,

his methods fail to contribute anything of value to his

4

cause.” McCleskey v. Zant at 372 (emphasis in original).

(J.A. 169).

The court also found the Respondent presented direct

rebuttal evidence to Baldus’ theory that contradicted any

prima facie case of system-wide discrimination, if one had

been established. McCleskey v. Zant at 373.

In examining the issues, the Eleventh Circuit Court of

Appeals assumed, but did not decide, that the research

was valid because there was no need to reach the question

of the validity of the research due to the court’s legal

analysis. The court specifically complimented the district

court on its thorough anaylsis of the studies and the evi

dence. The Eleventh Circuit observed that the first study,

the Procedural Reform Study, revealed no race of de

fendant effects whatsoever and revealed unclear race of

victim effects. McCleskey v. Kemp, 753 F.2d 877, 887 (11th

Cir. 1985) (en banc). As to the Charging and Sentencing

Study, the court concluded, ‘ ‘ There was no suggestion that

a uniform institutional bias existed that adversely affected

defendants in white victim cases in all circumstances, or a

black defendant in all cases.” Id. Finally, the court con

cluded the following in relation to the data specifically re

lating to the county in which the Petitioner was convicted,

that is, Fulton County, Georgia:

Because there were only ten cases involving police

officer victims in Fulton County, statistical analysis

could not be utilized effectively. Baldus conceded that

it was difficult to draw any inference concerning the

overall race effect in these cases because there had

been only one death sentence. He concluded that based

on the data there was only a possibility that a racial

factor existed in McCleskey’s case.

Id. at 887 (emphasis in original).

5

Any further factual or procedural matters will be

discussed as necessary in the subsequent portion of the

brief.

•--------------- o----------------

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

Although the petition in the instant case lists five

questions presented, the main focus of this case is simply

one of whether there has been racial discrimination in the

application of the death penalty in Georgia and, in par

ticular, whether there was racial discrimination in the im

position of the death penalty upon the Petitioner. An

other way of looking at this issue is whether the Petitioner

was selectively prosecuted and sentenced to death based

on his race and that of the victim or whether Petitioner’s

sentence is disproportionate. Regardless of the standard

to be applied, an appropriate consideration is the intent

of the decision-makers in question. A review of the cases

of this Court dealing with death penalty statutes shows

that the general arbitrariness and capriciousness which

concerned the Court in 1972 is no longer a consideration

if a state follows a properly drawn statute and if the

jury’s discretion is properly channeled. Thus, the focus

in an Eighth Amendment analysis becomes a question of

whether the sentence in a given case is “ arbitrary” in the

sense of being an aberration. The evidence in the instant

case shows that the Georgia statutory scheme is function

ing as it was intended to function and that those cases

which are more severe are receiving stronger penalties

while the less severe cases are receiving lesser penalties.

There is no evidence to show that the Petitioner ’s sentence

6

in the instant ease was arbitrary or capricious and no evi

dence to show that either the prosecutor or the jury based

their decision on race.

In relation to an equal protection context, it has al

ways been recognized that intentional and purposeful dis

crimination must be established for a constitutional viola

tion to be proven. Although intent may be inferred from

circumstantial evidence, the circumstantial evidence must

be sufficient to establish a prima facie ease of discrimina

tion before intent will be inferred. Even if a prima facie

case is shown, the Petitioner would still have the ultimate

burden of proof after considering any rebuttal evidence.

In evaluating facts and circumstances of a given case,

the court must consider the totality of the circumstances

in determining whether the evidence is sufficient to find

intentional and purposeful discrimination. Although sta

tistics are a useful tool in many contexts, in the situation

presented involving the application of the death penalty,

there are simply too many unique factors relevant to each

individual ease to allow statistics to be an effective tool in

proving intentional discrimination. Furthermore, the Peti

tioner’s statistics in the instant case were found to be inval

id by the district court, which was the only court making

any factual findings in relation to those statistics. Thus,

the clearly erroneous standard should apply to those factu

al findings. Furthermore, when a plausible explanation is

offered, as it was in the instant case, that is, that white

victim cases are simply more aggravated and less miti

gated than black victim cases and that various factors

tainted the statistics utilized, statistics alone or a disparity

alone is clearly insufficient to justify an inference of dis

crimination. Furthermore, the statistics in question fail

7

to take into consideration significant factors. Thus, the

statistics in the instant case do not give rise to an infer

ence of discrimination.

When reviewing all of the evidence in the instant case,

it is clear that the findings of fact made by the district

court are not clearly erroneous and that the statistical

study in question should not be concluded to be valid so

as to raise any inference of discrimination. The Peti

tioner failed to make a prima facie showing of discrimina

tion and did not carry the ultimate burden of proof on the

factual question of intent. Furthermore, Petitioner simply

failed to show that his death sentence was arbitrary or

capricious or was the result of racial discrimination either

on the part of the prosecutor or on the part of the jury.

-------------------------------------o ---------------— -— —

ARGUMENT

I. STATISTICAL ANALYSES ARE INADE

QUATE AS A MATTER OF FACT AND LAW

TO PROVE DISCRIMINATION UNDER THE

FACTS OF THE INSTANT CASE.

Respondent submits that the type of statistical an

alyses utilized in the instant case are not appropriate in a

death penalty case when trying to evaluate the motivation

behind a prosecutor’s use of his discretion and the jury’s

subsequent exercise of discretion in determining whether

8

or not a death sentence should be imposed.1 Each death

penalty case is unique and even though statistics might be

useful in jury composition cases or Title VII employment

discrimination cases where there are a limited number of

factors that are permissibly considered, in the instant case

where the prosecutor has discretion to pursue a case

through the criminal justice system and can consider any

number of subjective factors and where a jury has com

plete discretion with regard to extending mercy, the sub

jective factors cannot be accounted for in a statistical

analysis such as that utilized by the Petitioner in the in

stant case. Thus, Respondent would submit that this

Court should completely reject the use of this type of sta

tistical analysis as inappropriate in this case.

Even in the cases that have utilized statistical analysis

in a context other than that present in the instant case, the

courts have acknowledged various concerns with these

analyses. This Court has recognized in another context,

‘ ‘ Statistical analyses have served and will continue to

serve an important role as one indirect indicator of racial

discrimination in access to service on governmental bod

ies, particularly where, as in the ease of jury service, the

duty to serve falls equally on all citizens.” Mayor of

Philadelphia v. Educational Equality League, 415 U.S.

Respondent submits that a claim of discrimination based

on race of victim is not cognizable under the circumstances of

the instant case. At least one circuit court has specifically re

jected statistical evidence based on the race of the victim, find

ing that the defendant lacked standing. Britton v. Rogers, 631

F.2d 572, 577 n.3 (5th Cir. 1980), cert, denied, 451 U.S. 939

(1981). Even those justices raising a question of possible racial

discrimination in Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972), seemed

to focus on race of the defendant and not race of the victim.

Thus, Respondent submits that the instant claim is not cognizable

due to the lack of standing.

9

605, 620 (1974) (emphasis added). In the instant case,

however, there is no such uniform “ duty” as in the jury

composition cases, as all citizens are certainly not equally

eligible for a death sentence, nor are even all perpetra

tors of homicides or murders equally eligible for a death

sentence.

A central case regarding the use of statistics by this

Court arises in International Brotherhood of Teamsters v.

United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977). Again, this was in the

context of a Title VII action and not in a ease such as the

instant one involving so many subjective factors. The

Court noted prior approval of the use of statistical proof

“ where it reached proportions comparable to those in this

case to establish a prima facie case of racial discrimination

in jury selection cases.” Id. at 339. The Court also noted

that statistics were equally competent to prove employ

ment discrimination, which once again is different from

the type of discrimination sought to be proved in the in

stant case. The Court specifically concluded, “ We caution

only that statistics are not irrefutable; they come in in

finite variety and like any other kind of evidence, they

may be rebutted. In short their usefulness depends on all

of the surrounding facts and circumstances.” Id. at 340.

Thus, it is imperative to examine all of the facts and cir

cumstances to determine whether the statistics in a given

case are even useful for conducting the particular analy

sis. In Teamsters, supra, the Court also had 40 specific

instances of discriminatory action to consider in addition

to the statistics and noted that even “ fine tuning of the

statistics could not have obscured the glaring absence of

minority line drivers.” Id. at 342 n.23. Thus, the Court

did not focus exclusively on the statistics.

10

Problems have also been noted revolving aronnd the

particular use of statistics in any given case, many of

which occur in the studies presented to the district court

in the case at bar. In Basemore v. Friday, — U.S. —, 106

S.Ct. 3000 (1986), the Court examined regression analyses

and concluded that “ the omission of variables from a re

gression analysis may render the analysis less probative

than it otherwise might be” while noting that this would

not generally make the analysis inadmissible. Id. at 3009.

The Court did go on to note that there could be some cases

in which the regression was so incomplete as to be inad

missible as irrelevant.

Circuit courts have also utilized statistics but have

continually urged caution in their utilization even in jury

selection and Title VII cases. Also, the courts frequently

had other data on which to rely in addition to the statisti

cal analyses. See United States v. Ironworkers Local 86,

443 F.2d 544 (9th Cir. 1971); Wade v. Mississippi Coopera

tive Extension Service, 528 F.2d 508 (5th Cir. 1976). The

circuit courts have also recognized that statistical evidence

can be part of the rebuttal case itself. The Fifth Circuit

Court of Appeals examined a Title VII case in which the

statistics relied upon by the plaintiff actually formed the

very basis of the defendant’s rebuttal case, that is that

there was a showing that the statistics were not reliable.

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission v. Datapoint

Corporation, 570 F.2d 1264 (5th Cir. 1978). In that case,

the court noted “ while statistics are an appropriate

method of proving a prima facie case of racial discrimina

tion, such statistics must be relevant, material and mean

ingful, and not segmented and particularized and fash

ioned to obtain a desired conclusion.” Id. at 1269. See

11

also Johnson v. Uncle Ben’s Inc,, 628 F.2d 419 (5th Cir.

1980).

Circuit courts have also noted that due to the “ in

herently slippery nature of statistics” they are also sub

ject to misuse. See Wilkins v. University of Houston, 654

F.2d 388 (5th Cir. Unit A 1981). In particular, that court

focused on the fact that even though multiple regression

analysis was a sophisticated means of determining the

effects of factors on a particular variable, such an analy

sis was subject to misuse and should be employed with

great care. Id. at 402-3. Other courts have emphasized

that even though every conceivable factor did not have to

be considered in a statistical analysis, the minimum ob

jective qualifications had to be included in the analysis

(in an employment context). “ [W]hen the statistical evi

dence does not adequately account for ‘ the diverse and

specialized qualifications necessary for [the positions

in question],’ strong evidence of individual instances of

discrimination becomes vital . . . .” Valentino v. United

States Postal Service, 674 F.2d 56, 69 (D.C.Oir. 1982).

The Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals has examined

statistical analyses and noted that the probative value of

multiple regressions depends upon the inclusion of all

major variables likely to have a large effect on the de

pendant variable and also depends on the validity of the

assumptions that the remaining effects were not corre

lated with independent variables included in the analysis.

The court also specifically questioned the validity of step

wise regressions, such as those used in the instant pro

ceedings. Eastland v. Tennessee Valley Authority, 704

F.2d 613, 621 n .ll (11th Cir. 1983). The court emphasized

12

that a study had to begin with a decent theoretical idea of

what variables were likely to be important.

Thus, examining a statistical analysis depends in part

on the question of whether the analysis incorporated the

requisite variables and whether there is an appropriate

theoretical base for the incorporation of the variables. As

found by the district court in the instant case, none of the

models utilized by Professor Baldus necessarily reflected

the way the system acted and specifically did not include

important factors, such as credibility of the witnesses,

the likelihood of a jury verdict, and subjective factors

which could be appropriately considered by a prosecutor

and by a jury. Thus, the district court properly rejected

the statistical analyses in question.

More difficult problems arise with the attempted use

of statistics in death penalty cases. In 1968 problems were

found with the utilization of statistics, specifically pre

sented by Marvin Wolfgang. The circuit court concluded

that the study presented in that case was faulty for vari

ous reasons, including failing to take variables into account

and failing to show that the jury acted with racial dis

crimination. The court also emphasized that it was con

cerned in that case with the defendant’s sentencing out

come and only his case. The court concluded that the sta

tistical argument did nothing to destroy the integrity of

the trial. Maxwell v. Bishop, 398 F.2d 138 (8th Cir. 1968),

remanded on other grounds, 398 U.S. 262 (1970).

An additional factor in the death penalty situation

comes from the unique nature of the death sentence it

self and the capital sentencing system. In McGautha v.

California, 402 U.S. 183 (1971), the Court noted the diffi

13

culty in identifying beforehand those characteristics which

could be utilized by a sentencing authority in imposing

the death penalty and the complex nature of those fac

tors. Other circuit courts have rejected statistical an

alyses due to just such a reason. See Spinkellink v. Wain-

wright, 578 F.2d 582 (5th Cir. 1978); Smith v. Balkcom,

660 F.2d 584 (5th Cir. 1981), on rehearing, 671 F.2d 858

(5th Cir. Unit B, 1982); McCorquodale v. Balkcom, 525

F.Supp. 408 (N.D.Ga. 1981), affirmed, 721 F.2d 1493 (11th

Cir. 1983).

In cases upholding the constitutionality of various

death penalty schemes, the Court has recognized that it is

appropriate to allow a sentencer to consider every aspect

regarding the defendant and the crime in question in exer

cising the discretion as to whether to extend mercy or im

pose the death penalty. Thus, in Eddings v. Oklahoma,

455 U.S. 104 (1982) the Court noted that the rule set down

in Lockett v. Ohio, 438 U.S. 586 (1978) was a product of a

“ history reflecting the law’s effort to develop a system

of capital punishment at once consistent and principled

but also humane and sensible to the uniqueness of the indi

vidual.” Eddings, supra at 110.

Other factors that have been recognized by courts as

being appropriate in a death penalty case and in the prose

cutor’s discretion are the willingness of a defendant to

plead guilty, as well as the sufficiency of the evidence

available. Shaw v. Martin, 733 F.2d 304 (4th Cir. 1984).

As recently as 1986, this Court has acknowledged that in

a capital sentencing proceeding the jury must make a

“ highly subjective, ‘ unique, individualized judgment re

garding the penalty that a particular person deserves.’ ”

Caldwell v. Mississippi, 472 U.S. —, 105 S.Ct. 2633, 2645-6

14

n.7 (1985); Turner v. Murray, — U.S. —, 106 S.Ct. 1683

(1986). In this context, “ it is the jury that must make the

difficult, individualized judgment as to whether the de

fendant deserves the sentence of death.” Turner v. Mur

ray, supra 106 S.Ct. at 1687. This focuses on what has

long been recognized as one of the most important func

tions that a jury can perform, that is, “ to maintain a link

between contemporary community values and the penal

system—a link without which the determination of punish

ment could hardly reflect ‘ the evolving standards of de

cency that mark the progress of a maturing society.’ ”

Witherspoon v. Illinois, 391 U.S. 510, 519 n.15 (1968),

quoting, Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86,101 (1958).

Thus, the myriad of factors that are available for

consideration by a prosecutor in exercising his discretion

and by a jury in determining whether to extend mercy to

a given defendant simply makes the utilization of these

types of statistical analyses unworkable in a death penalty

context. It is simply impossible to quantify subjective

factors which are properly considered both by the prosecu

tor and by the jury in reaching these determinations. In

fact, the evidence in the instant case fails to take into ac

count these subjective factors, including the information

known to the decision-maker, the likelihood a jury would

return a verdict in a particular case, the possible credi

bility of individual witnesses, the availability of witnesses

at the time of trial, the actual sufficiency of the evidence

as determined by the prosecutor himself as well as num

erous other factors.

In addition to all the above, commentators have also

recognized that many of the factors present in the instant

case cause problems with utilizing statistical analyses.

15

Professor Baldus himself has noted that “ statistical so

phistication is no cure for flaws in model construction and

research design.” Baldus & Cole, A Comparison of the

Work of Thorsten Sellin and Isaac Ehrlich on the Deter

rent Effect of Capital Punishment, 85 Yale L. J. 170, 173

(1975). In that same article, Professor Baldus acknowl

edged that the deterrent effect of capital punishment was

just such a type of study that would he best suited by

simpler methods of study than statistical analysis. Id.

Other authors have questioned the validity of statistical

methods which include inappropriate variables in the analy

sis as well as those which fail to include necessary vari

ables. See Pinkelstein, The Judicial Reception of Multi

ple Regression Studies in Race and Sex Discrimination

Cases, 80 Colum. L.Rev. 737, 738 (1980). Other authors

have also agreed with the testimony of the experts in this

case regarding the problems presented by multieollinearity

as well as the problems in utilizing stepwise regressions.

See Fisher, Multiple Regression in Legal Proceedings, 80

Colum. L.Rev. 702 (1980); See also Gr. Wesolowsky, Multi

ple Regression Analysis of Variance (1976); A. Gold-

berger, Topics in Regression Analysis (1968).

Finally, certain authors have questioned the utilization

of statistical analyses even in employment discrimination

cases noting “ it may be impossible to gather data on many

of these differences in qualifications and preferences.

Consequently, there will likely be alternative explanations,

not captured by the statistical analysis, for observed dis

parities. . . . These alternative explanations must be taken

into consideration in assessing the strength of the in

ference to be drawn from the statistical evidence.” Smith

16

and Abram, Quantitative Analysis and Proof of Employ

ment Discrimination, 1981 TJ.I11. L.Rev. 33, 45 (1981).

Respondent submits that a consideration of the sta

tistical analysis in the instant case reflects that it simply

fails to comply with the appropriate conventions utilized

for this type of analysis in that it fails to include appropri

ate variables, fails to utilize interaction variables, fails

to specify a relevant model and has other fallacies, includ

ing multicollinearity which render the analysis nonpro-

bative at best. As noted by a statistician in an article re

garding race and sex discrimination and regression analy

sis :

It should be again emphasized that a statistical analy

sis provides only a limited part of the total picture that

must be presented to prove or disprove discrimina

tion. . . . “ No statistician or other scientist should

ever put himself/herself in a position of trying to

prove or disprove discrimination.”

McCabe, The Interpretation of Regression Analysis Re

sults in Sex and Race Discrimination Problems, 34 Amer.

Stat. 212, 215 (1980).

II. THE STATISTICAL ANALYSES IN THE IN

STANT CASE ARE INSUFFICIENT TO

PROVE RACIAL DISCRIMINATION.

As noted previously, courts and commentators have

expressed reservations about the use of statistics in at

tempting to prove discrimination. Respondent submits

that even if the Court concludes statistical analysis is ap

propriate in a death penalty context, the “ statistics” pre

sented to the district court are so flawed as to have no pro-

17

Native value and, thus, cannot satisfy the Petitioner’s bur

den of proof.2

Petitioner claims that the studies in question are the

product of carefully tailored questionaires resulting in the

collection of over 500 items of information on each case.

The Respondent has proven, and the district court found,

that the data bases are substantially flawed, inaccurate

and incomplete.

As noted previously, statistical analyses, particularly

multiple regressions, require accurate and complete data

to be valid. Neither was presented to the district court.

Design flaws were shown in the questionnaires utilized to

gather data. There were problems with the format of

critical items on the questionnaires, such that there was

an insufficient way to account for all factors in a given

case. “ An important limitation placed on the data base

was the fact that the questionnaire could not capture every

nuance of every case.” McCleshey v. Zant, supra at 356.

(J.A. 136).

Further, the sources of the information were notice

ably incomplete. Even though the Petitioner insisted that

2lt is clear that the findings by the district court in regard

to the question of intent and the evaluation of the statistical

analysis are subject to the clearly erroneous rule. In United

States v. United States Gypsum Co., 333 U.S. 364 (1948), the

Court acknowledged that the clearly erroneous rule set forth in

rule 52(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure applied to

factual findings. "A finding is 'clearly erroneous' when although

there is evidence to support it, the reviewing court on the en

tire evidence is left with the definite and firm conviction that a

mistake has been committed." Id. at 395. This principle has

been held to apply to factual findings regarding motivations

of parties in Title VII actions and it has been specifically held

that the question of intentional discrimination is a pure question

of fact. Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273, 287-8 (1982).

18

he relied on State sources, obviously those sources were not

designed to provide detailed information on each case. As

found by the district court, “ the information available to

the coders from the Parole Board files was very summary

in many respects.” McCleskey v. Zant, supra at 356. (J.A.

137). These summaries were brief and the police reports

from which the Parole Board summaries were prepared

were usually only two or three pages long. (F.H.T. 1343:

J.A. 137). As found by the district court:

Because of the incompleteness of the Parole Board

studies, the Charging and Sentencing Study contains

no information about what a prosecutor felt about the

credibility of any witnesses. R 1117. It was occasion

ally difficult to determine whether or not a co-perpe

trator testified in the case. One of the important

strength of the evidence variables coded was whether

or not the police report indicated clear guilt. As the

police reports were missing in 75% of the cases, the

coders treated the Parole Board summary as the po

lice report. R 493-94. Then, the coders were able to

obtain information based only upon their impressions

of the information contained in the file. R 349.

McCleskey v. Zant, supra at 357. (J.A. 137).

Furthermore, questionaires were shown to be mis

coded. It was also shown there were differences in judg

ment among the coders. (F.H.T. 387).

Respondent also established that there were numerous

inconsistencies between the coding for the Procedural Re

form Study and the Charging and Sentencing Study. (J.A.

77-80; S.E. 78; Respondent’s Exhibit 20A). These oc

curred in some variables generally considered to be im

portant in a sentencing determination.

19

A further problem with the data base is due to the

large number of unknowns. Although Petitioner claims to

have collected information on over 500 variables relating

to each case, the evidence showed that in the Charging and

Sentencing Study alone there are an average of at least 33

variables coded as unknown for each questionnaire. (J.A.

139). A review of Respondent’s Exhibits Nos. 17A and 18A

shows the extent to which unknowns pervade the so-called

complete data base. For example, in the Charging and

Sentencing Study there are 445 cases in which it was un

known if there was a plea bargain. (S.E. 73-74; J.A. 69-

74). Further complicating the data is the fact that Baldus

arbitrarily coded unknowns as if the information did not

exist without any knowledge as to whether the information

was known to the prosecutor or jury.

Even though attempts were made in the district court

to discount the unknowns, Petitioner did not succeed. In

fact the district court concluded the so-called “ worst case”

analysis failed to prove that the coding decisions on the

unknowns had no effect on the results. (J.A. 142). The

Respondent also introduced evidence that the correct sta

tistical technique would be to discard the cases with un

knowns in the variables being utilized in the analysis and

not utilize the cases in the analysis.3

The district court also concluded that no models of

fered by the Petitioner were sufficiently predictive as to

be probative. (J.A. 149). As noted previously, regres

sions must include relevant variables to be probative. See

3This is precisely the reason no independent model or re

gression analysis was presented by the Respondent. The data

base was simply too; flawed and eliminating cases with un

knowns reduced the sample size to the extent that a valid

analysis was futile.

Basemore v. Friday, supra. No model was used which,

accounted for several significant factors because the in

formation was not in the data base, i.e., credibility of wit

nesses, likelihood of a jury verdict, strength of the evi

dence, etc.4 Many of the small-scale regressions simply

include a given list of variables with no explanation given

for their inclusion. Even the large-scale 230-variable re

gression has deficiencies. “ It assumes that all of the in

formation available to the data-gathers was available to

each decision-maker in the system at the time that deci

sions were made.” McCleskey v. Zant, supra at 361. (J.A.

146). This is simply an unrealistic view of the criminal

justice system which fails to consider simple issues such

as the admissibility of evidence. Further the adjusted

r-squared, which measures what portion of the variance

in the dependent variable is accounted for by the inde

pendent variables in the model, even in the 230-variable

model, is only approximately .5. (J.A. 147). Petitioner

also fails to show the coefficients of all variables in the

regressions.

Major problems are also presented due to multi-

collinearity in the data. See Fisher, supra. (J.A. 105-111).

Multicollinearity will distort the regression coefficients

in an analysis. (J.A. 106). It was virtually admitted that

there is a high correlation between the race of the victim

variable and many other variables in the study. According

to the testimony of Respondent’s experts, this was not

accounted for by any analysis of Baldus or Woodworth.

Various experiments conducted by Dr. Katz confirmed the

20

4Although the second study purports to include strength

of the evidence variables, there are such a high number of un

knowns that it cannot be considered to be effectively included

in any analysis.

21

correlation between aggravating factors and white victim

cases and mitigating factors with black victim, cases. See

F.H.T. 1472, et seq.; Respondent’s Exhibits 49-52. The

district court specifically found neither Woodworth or

Baldus had sufficiently accounted for multieollinearity in

any analysis.

Petitioner has asserted that there is an average twenty

point racial disparity in death sentencing rates which he

asserts should constitute a violation of the Eighth or Four

teenth Amendments. As noted previously, the statistical

analyses themselves have not been found to be valid by

any court making such a determination; thus, this analy

sis is questionable at best. Furthermore, focusing on the

so-called “ twenty percentage point” effect misconstrues

the nature of the study presented. The twenty percentage

point “ disparity” occurred in the so called “ mid-range”

of cases. This analysis attempted to exclude the most ag

gravated cases from its consideration as well as the most

mitigated cases. The analysis did not consider whether the

cases were actually eligible for a death sentence under state

law, but was a consideration of all cases in the study which

have been indicted either for murder or voluntary man

slaughter.

A primary problem shown with the utilization of this

“ mid-range” analysis is the fact that Petitioner failed to

prove that he was comparing similar cases in this analysis.

By virtue of the previously noted substantial variables

which were not included in the analysis, it can hardly be

determined that the cases were similar.

Further, this range of cases referred to by the Pe

titioner was constructed based on the index method uti

lized extensively by Professors Baldus and Woodworth.

22

Dr. Katz testified for the Respondent concerning this in

dex method and noted that an index is utilized to attempt

to rank different eases in an attempt to conclude that cer

tain cases had either more or less of a particular attribute.

(J.A. 87). The numbers utilized in the comparisons men

tioned above were derived from these indices and the num

bers would “ purport to represent the degree for a level of

aggravation and mitigation in each case for the purpose

of ranking these cases according to those numbers.” Id.

Dr. Katz noted that Professor Baldus had utilized re

gression analysis to develop the indices and had used a

predicted outcome to form the index for aggravation and

mitigation. Through a demonstration conducted by Dr.

Katz utilizing four sample regressions, it was shown that

the index method could be shaped to give different rank

ings from the same cases depending on what variables

might be included in a particular regression. Through the

demonstration. Dr. Katz showed that by including dif

ferent variables in the model, the actual values for the

index would change. “ [T]he purpose of this was to show

that at any stage, what is happening with the regression

in terms of the independent variables it has available to

it, is that it is trying to weigh the variables or assign co

efficients to the variables so that the predicted outcomes

for the life sentence cases will have zero values and the

predicted outcomes for the death sentence cases will have

one value, regardless of the independent variables that

it has to work with.” (J.A. 98-9). The examination of

this testimony as well as the exhibits in connection there

with shows that the index method itself is capable of mis

use and abuse and. depending on the particular regression

equation utilized, the index values can be different. No

23

adequate explanation was provided for the particular var

iables included in the regression analysis so as to justify

utilizing the index values. Thus, it was simply not shown

that the cases being compared to develop this “ mid-range”

were actually similar. See McGleskey v. Zant, supra at

375-6. (J.A. 175).

Additionally, the .06 figure referred to by the Petition

er does not represent a true disparity. The .06 so-called

“ disparity” does not reflect any particular comparison

of subgroups of cases. Further the .06 figure is a weight

which is subject to change when variables are added to

or subtracted from the model. (J.A. 233).

Regardless of the standard applied or the propriety

of utilizing statistics in the instant case, the above shows

that the data base is substantially flawed so as to be in

adequate for any statistical analysis. Any results of any

such analysis are thus fatally flawed and prove nothing

about the Georgia criminal justice system.

III. THE ARBITRARINESS AND CAPRICIOUS

NESS CONCERNS OF FURMAN V. GEORGIA,

403 U.S. 238 (1972), ARE REMOVED WHEN A

STATE PROPERLY FOLLOWS A CONSTITI-

TIONAL SENTENCING PROCEDURE.

Throughout the history of Eighth Abendment juris

prudence this Court has recognized, “ [d ifficulty would

attend the effort to define with exactness the extent of the

constitutional provision which provides that cruel and un

usual punishments shall not be inflicted . . . .” Wilkerson

v. Utah, 99 U.S. 130, 135-6 (1878). Furthermore, “ [t]he

cruelty against which the Constitution protects a con

victed man is cruelty inherent in the method of punish

24

ment, not the necessary suffering involved in any method

employed to extinguish life humanely.” Louisiana ex rel.

Francis v. Resweber, 329 U.S. 459, 464, rhng. denied, 330

U.S. 853 (1947). Members of the Court have not agreed

as to the extent of the applicability of the Eighth Amend

ment. In Trop v. Dulles, 356 U.S. 86 (1958), the Court de

termined that the question was whether the penalty under

examination in that case subjected the individual to a fate

“ forbidden by the principle of civilized treatment guaran

teed by the Eighth Amendment.” Id. at 99. The Court

also went on to note that the Eighth Amendment was not

a static concept but that the amendment “ must draw its

meaning from evolving standards of decency that mark

the progress of a maturing society. ’ ’ Id. at 101.

The Eighth Amendment embodies “ broad and idealis

tic concepts of dignity, civilized standards, humanity and

decency . . . .” Estelle v. Gamble, 429 U.S. 97 (1976). In

Ingraham v. Wright, 430 U.S. 651 (1977), the Court

acknowledged that the Eighth Amendment prohibition

against cruel and unusual punishment circumscribed the

criminal process in three ways: (1) it limits the particular

kind of punishment that can be imposed on those con

victed; (2) the amendment proscribes punishment that

would be grossly disproportionate to the severity of the

crime; (3) the provision imposes substantive limits on

what can be made criminal and punished as such.

Not until Furman v. Georgia, 408 U.S. 238 (1972), was

the Court squarely confronted with a claim that the death

penalty itself violated the Eighth Amendment. The hold

ing of the Court in that case was simply that the carrying

out of the death penalty in the cases before the Court con

stituted cruel and unusual punishment. Id. at 239.

25

In Gregg v. Georgia, 428 U.S. 153 (1976), this Court

specifically examined the Georgia death penalty scheme.

In so doing, the Court examined the history of the Eighth

Amendment and the opinion in Furman v. Georgia. The

Court noted that the Eighth Amendment was to he inter

preted in a flexible and dynamic manner and that the

Eighth Amendment was not a static concept. The Court

went on to note, however, that the Eighth Amendment

“ must be applied with an awareness of the limited role

played by courts.” Id. at 174. In upholding the Georgia

statute, the Court acknowledged that Furman established

that the death sentence could not be imposed by sentencing

proceedings “ that created a substantial risk that it would

be inflicted in an arbitrary and capricious manner.” Id. at

188. The Court compared the death sentences in Furman

as being cruel and unusual in the same way as being struck

by lightning would be cruel and unusual. The Court fur

ther noted that Furman mandated that where discretion

was afforded to a sentencing body, that discretion had to

be suitably directed and limited so as to minimize the risk

of wholly arbitrary and capricious action. Finally, the

Court acknowledged that in each stage of the death sen

tencing process an actor could make a decision which would

remove the defendant from consideration for the death

penalty. “ Nothing in any of our cases suggests that the

decision to afford an individual defendant mercy violates

the Constitution. Furman held only that in order to mini

mize the risk that the death penalty would be imposed on

a capriciously selected group of offenders, the decision

to impose it had to be guided by standards so that the

sentence authorized would focus on the particularized cir

cumstances of the crime and defendant.” Gregg, supra

26

at 199. The Court further emphasized that “ [t]he isolated

decision of a jury to afford mercy does not render uncon

stitutional a death sentence imposed upon defendants who

were sentenced under a system that does not create a sub

stantial risk of arbitrariness or caprice . . . . The propor

tionality review substantially eliminates the possibility

that a person will be sentenced to die by the action of an

aberrant jury.” Id. at 203. The Court finally found that

a jury could no longer wantonly and freakishly impose a

death sentence as it was always circumscribed by the

legislative guidelines.

The same time as the Court decided Gregg v. Georgia,

supra, it also decided Proffitt v. Florida, 428 U.S. 242

(1976). The Court again noted that the “ requirements

of Furman are satisfied when the sentencing authority’s

discretion is guided and channelled by requiring the ex

amination of specific factors that argue in favor of or

against the imposition of the death penalty, thus eliminat

ing total arbitrariness and capriciousness in its imposi

tion.” Id. at 258.

Subsequently, the Court actually criticized states for

restricting the discretion of the juries, thus, outlawing

statutes providing for mandatory death sentences upon

conviction of a capital offense. See Woodson v. North

Carolina, 428 U.S. 280 (1976). The Court has also pro

hibited death penalty procedures which restrict the con

sideration of mitigating circumstances, consistently em

phasizing that there must be an individualized considera

tion of both the offense and the offender before a death

sentence could be imposed. Thus, in Lockett v. Ohio, 438

U.S. 587 (1978), the plurality noted that the joint opinion

in Gregg, Proffitt and other cases concluded that in order

27

to comply with Furman the “ sentencing procedure should

not create a substantial risk that the death penalty was

inflicted in an arbitrary manner, only that the discretion

be directed and limited so that the sentence was imposed

in a more consistent and rational manner. . . . ” LocJcett,

supra at 597.

This Court has considered death penalty cases in an

Eighth Amendment context, but from a different perspec

tive than the arbitrary and capricious infliction of a pun

ishment as challenged in Furman. In Godfrey v. Georgia,

446 U.S. 420 (1980), the Court was concerned with a par

ticular provision of Georgia law and the question of

whether the Georgia Supreme Court had followed the

statute that was designed to avoid the arbitrariness and

capriciousness prohibited in Furman. This Court essen

tially concluded that the state courts had not followed

their own guidelines. This Court concluded that the death

sentence should appear to be and must be based on reason

rather than caprice and emotion. As the Georgia courts

had not followed the appropriate statutory procedures in

narrowing discretion in that case, the Court concluded

that the sentence was not permissible under the Eighth

Amendment. The Court did not deviate from its prior

holding in Gregg, supra, that by following a properly

tailored statute the concerns of Furman were met.

The Court considered the death penalty in an Eighth

Amendment context in Enmund v. Florida, 458 U.S. 782

(1982). The Court, however, did not consider the “ arbi

trary and capricious” aspect but focused on the question

of the disproportionality of the death penalty for En

mund’s own conduct in that case. Thus, the Court essen

28

tially concluded that the death penalty was disproportion

ate under the facts of that case.

In California v. Ramos, 463 U.S. 992, 999 (3983), the

Court noted that “ [i]n ensuring that the death penalty is

not meted out arbitrarily or capriciously, the Court’s prin

cipal concern has been more with the procedure by which

the State imposes the death sentence than with substantive

factors the State lays before the jury as a basis for im

posing death. . . . ” Thus, the Court again focused on the

state procedure in question and noted that excessively

vague sentencing standards could lead to the arbitrariness

and capriciousness that were condemned in Furman.

Further, in particular reference to the study in the

instant ease, Justice Powell observed:

No one has suggested that the study focused on this

case. A “ particularized” showing would require—

as I understand it—that there was intentional race

discrimination in indicting, trying and convicting [the

defendant], and presumably in the state appellate and

state collateral review that several times followed the

trial. . . . Surely, no contention can be made that the

entire Georgia judicial system, at all levels, operates

to discriminate in all cases. Arguments to this effect

may have been directed to the type of statutes ad

dressed in Furman. As our subsequent cases make

clear, such arguments cannot be taken seriously un

der statutes approved in Gregg.

Stephens v. Kemp, — IJ.S. — 104 S.Ct. 562 n.2 (1983)

(Powell, J., dissenting from the granting of a stay of exe

cution). Justice Powell went on to note “ claims based

merely on general statistics are likely to have little or no

merit under statutes such as that in Georgia.” Id.

29

Respondent submits that reviewing all of the Court’s

Eighth Amendment jurisprudence, particularly in the death

penalty context reflects that in order to establish a claim

of arbitrariness and capriciousness sufficient to violate

the cruel and unusual punishment provision of the Eighth

Amendment, it must be established that the state failed to

properly follow a sentencing procedure which was suffi

cient to narrow the discretion of the decision-makers. As

long as the state follows such a procedure, the arbitrari

ness and capriciousness which were the concern in Fur

man v. Georgia, supra, have been minimized sufficiently to

preclude a constitutional violation, particularly under the

Eighth Amendment. An Eighth Amendment violation

would result in the “ arbitrary and capricious” context,

only if the statutory procedure either was insufficient it

self or the appropriate procedures were not followed. Other

death penalty cases under the Eighth Amendment deal

with different aspects of the cruel and unusual punish

ment provision, such as disproportionality or excessive

sentences in a given case. That is simply not the focus

of the inquiry here. Under the circumstances of the in

stant case, the Petitioner has not even asserted that Geor

gia’s procedures themselves are unconstitutional, nor has

the Petitioner asserted that those procedures which were

approved in Gregg v. Georgia, supra, were not followed in

the instant ease. Thus, there can be no serious contention

that there is an Eighth Amendment violation under the

circumstances of this case. This is particularly true in

light of the testimony of Petitioner’s own expert that the

Georgia charging and sentencing system sorts cases on

rational grounds. (F.H.T. 1277; J.A. 154).

30

Insofar as the Petitioner would attempt to assert some

type of racial discrimination under the Eighth Amendment

provisions, there should be a requirement of a focus on

intent in order to make this sentence an “ aberrant” sen

tence so as to classify it as arbitrary and capricious. A

simple finding of disparate impact is insufficient to make

a finding of arbitrariness and capriciousness such as was

the concern in Furman, supra, particularly when a prop

erly drawn statute has been utilized and properly followed.

Only a showing of purposeful or intentional discrimina

tion can be sufficient to find a constitutional violation un

der these circumstances.

No Eighth Amendment violation can be shown in the

instant case as Petitioner ’s own witness testified that the

system acted in a rational manner. As shown by the

analyses conducted by Professor Baldus and Dr. Wood-

worth, the more aggravated cases were moved through the

charging and sentencing system and the most aggravated

cases generally received a death sentence. The more miti

gated cases on the other hand dropped out at various

stages in the system receiving lesser punishments. Thus,

this system does function in a rational fashion. Further

more, it has not been shown that the death sentence in the

instant case was arbitrary or capricious in any fashion.

The jury found beyond a reasonable doubt that there were

two statutory aggravating circumstances present. The

evidence also shows that the victim was shot twice, includ

ing once in the head at fairly close range. The evidence

tended to indicate that Petitioner hid and waited for the

police officer and shot him as the officer walked by. This

was an armed robbery by four individuals of a furniture

31

store in which several people were, in effect, held hostage

while the robbers completed their enterprise. It was thor

oughly planned and thought out prior to the robbery occur

ring. Furthermore, the Petitioner had prior convictions

for robbery before being brought to this trial. One of

Petitioner’s co-perpetrators testified against him at trial

and a statement of the Petitioner was introduced in which

he detailed the crime and even boasted about it. (J.A. 113-

115). Thus, under the factors in this case it is clear that

Petitioner’s sentence is not arbitrary or capricious and

there is clearly no Eighth Amendment violation.

IV. PROOF OF DISCRIMINATORY INTENT IS

REQUIRED TO ESTABLISH AN EQUAL

PROTECTION VIOLATION.

It is well recognized that “ [a] statute otherwise neu

tral on its face, must not be applied so as to invidiously

discriminate on the basis of race.” Washington v. Davis,

426 U.S. 229, 241 (1976), citing Yiek Wo v. Hopkins, 118

U.S. 356, 369 (1886). This Court has consistently recog

nized, however, that in order to establish a claim of dis

crimination under the Equal Protection Clause, there must

be proof that the challenged action was the product of dis

criminatory intent. See Washington v. Davis, supra.

In 1962, the Court examined what was essentially an

allegation of selective prosecution and recognized, “ the

conscious exercise of some selectivity in enforcement is not

in itself a federal constitutional violation.” Oyler v. Boles,

368 U.S. 448, 456 (1962). In cases finding an equal pro

tection violation, it is consistently recognized that the bur

den is on the petitioner to prove purposeful discrimination

under the facts of the case. See Whitus v. Georgia, 385

32

U.S. 545 (1967). The Court specifically has recognized

that the standard applicable to Title YII cases does not

apply to equal protection challenges. “We have never held

that the constitutional standard for adjudicating claims of

invidious racial discrimination is identical to standards

applicable under Title VII. . . .” Washington v. Davis,

supra, 426 U.S. at 239. The Court went on in that case to

note that the critical purpose of the equal protection clause

was the “prevention of official conduct discriminating on

the basis of race.” Id. The Court emphasized that the

cases had not embraced the proposition that an official

action would be held to be unconstitutional solely because

it had a racially disproportionate impact without regard

to whether the facts showed a racially discriminatory pur

pose. It was acknowledged that disproportionate impact

might not be irrelevant and that an invidious purpose

could be inferred from the totality of the relevant facts,

including impact, but “ [djisproportionate impact . . .

is not the sole touchtone of an invidious racial discrimina

tion forbidden by the Constitution. Standing alone it does

not trigger the rule [cit.] that racial classes are to be sub

jected to the strictest scrutiny. . . .” Id. at 242.

Again in Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482, 493

(1977), the Court held that “an official act is not uncon

stitutional solely because it has a racially disproportionate

impact.” (emphasis in original). Further, “ [pjroof of

racially discriminatory intent or purpose is required to

show a violation of the Equal Protection Clause.” Village

of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Develop

ment Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 265 (1977). In Washington v.

Davis the Court held that the petitioner was not required

to prove that the decision rests solely on racially discrim

inatory purposes, but that the issue did demand a “ sensi

tive inquiry into such circumstantial and direct evidence

of intent as may be available.” Id; Village of Arlington

Heights, supra. “Absent a pattern as stark as that in

Gomillion5 or Yick Wo, impact alone is not determinative,

(footnote omitted) and the court must look to other evi

dence.” Id. at 266. “ In many cases to recognize the lim

ited probative value of disproportionate impact is merely

to acknowledge the ‘heterogeneity’ of the Nation’s popu

lation.” Id. at 266 n.15.

The Court also acknowledged that the Fourteenth

Amendment guarantees equal laws, not necessarily equal

results. Whereas impact may be an important starting

point, it is purposeful discrimination that offends the Con

stitution. Personnel Administrator of Massachusetts v.

Feeney, 442 U.S. 256, 273-4 (1979). A discriminatory pur

pose “ implies more than intent as volition or intent as

awareness of the consequences. . . . It implies that the

decision makers selected or reaffirmed a particular course

of action at least in part because of not merely in spite

of its adverse effects on the identified group.” Id. at 279;

see also Wayte v. United States, — U.S. —, 105 S.Ct. 1524,

1532 (1985). The Court reemphasized its position in Rog

ers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982), in which the Court rec

ognized “the invidious quality of a law claimed to be ra

cially discriminatory must ultimately be traced to a racially

discriminatory purpose,” and acknowledged that a showing

of discriminatory intent was required in all types of equal

protection eases which asserted racial discrimination.

5Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960).

34

Thus, it is clear from all of the above that a discrim

inatory purpose, requiring more than simply an awareness

of the consequences, must be established in order to make

out a prima facie showing of discrimination under the

Equal Protection Clause, regardless of the type of equal

protection claim that is raised. The burden is on the in

dividual alleging this discriminatory selection to prove the

existence of the purposeful discrimination and this includes

the initial burden of establishing a prima facie case as

well as the ultimate burden of proof.

In relation to the question of an Equal Protection vi

olation, Petitioner has also failed to show intentional or

purposeful discrimination. The Petitioner presented evi

dence to the district court by way of the deposition of

the district attorney of Fulton County, Lewis Slaton.

Throughout his deposition, Mr. Slaton testified that the

important facts utilized by his office in determining wheth

er to proceed with a case either to indictment, to a jury

trial or to a sentencing trial, would be the strength of the

evidence and the likelihood of a jury verdict as well as

other facts. Mr. Slaton observed that in a given case there

could exist the possibility of suppression of evidence ob

tained pursuant to an alleged illegal search warrant which

would also affect the prosecutor’s decision. (Slaton Dep. at

18). In determining whether to plea bargain to a lesser of

fense, Mr. Slaton testified that his office would consider

how strong the case was, how the witnesses would hold up

under cross-examination, what scientific evidence was avail

able, the reasons for the crime, the mental condition of the

parties, prior record of the defendant and the likelihood of

what the jury might do. Id. at 30. As to proceeding to a

death penalty trial, Mr. Slaton testified that first of all the

question was whether the case fell within the ambit of the

statute and then he examined the atrociousness of the

crime, the strength of the evidence and the possibility of

what the jury might do as well as other factors. Id. at 31.

He also specifically noted that his office did not seek the

death penalty very often, for one reason because the juries

in Fulton County were not disposed to impose the death

penalty. Id. at 32. He also specifically testified he did

not recall ever seeking a death penalty in a case simply

because the community felt it should be done and did not

recall any case in which race was a factor in determining

whether to seek a death penalty. Id. at 78.

This is a case in which the Petitioner has in effect by

statistics alone sought to prove intentional discrimination.

Although Petitioner has alleged anecdotal evidence was

submitted, in fact, little, if any, was presented to the dis

trict court outside the deposition of Lewis Slaton and one

witness who gave the composition of Petitioner’s trial

jury. As noted previously, Respondent submits that sta

tistics are not appropriate in this type of analysis and the

Petitioner’s statistics in this case are simply invalid; how

ever, regardless of that fact any disparity noted is simply

not of the nature of such a gross disparity as to compel an

inference of discrimination, unlike earlier cases before the

court. See e.g., Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364TT.S. 339 (1960).

Absent the ‘ ‘ inexorable zero” or a gross disparity similar

to that, this type of evidence under the unique circumstanc

es of a death penalty situation should not be sufficient to

find an inference of discrimination, particularly when both

lower courts have found that no intentional discrimination

was proven. Thus, Respondent submits that regardless of

36

the standard utilized, Petitioner has failed to meet this

burden of proof.

Regardless of the standard used for determining when

a prima facie case has been established, it is clear where

the ultimate burden of proof lies. Under the circumstances

of the instant case, it is clear that the ultimate burden of

proof rested with the Petitioner and he simply failed to

meet his burden of proof either to establish a prima facie

case of discriminatory purpose or to carry the ultimate

burden of proof by a preponderance of the evidence.

— --------------- — o ------------------------- -

37

CONCLUSION

For all of the above and foregoing reasons, the con

victions and sentences of the Petitioner should be affirmed

and this Court should affirm the decision of the Eleventh

Circuit Court of Appeals.

Respectfully submitted,

Mary B eth W estmoreland

Assistant Attorney General

Counsel of Record for Respondent

M ichael J. B owers

Attorney General

Marion 0 . Gordon

First Assistant Attorney General

W illiam B. H ill, Jr.

Senior Assistant Attorney General

Mary B eth W estmoreland

132 State Judicial Building

40 Capitol Square, S. W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30334

(404) 656-3349