Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education Memorandum of James E. Swann

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education Memorandum of James E. Swann, 1970. 3ffe9fa8-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/53f6bf19-236f-4435-b312-6d7835e6e122/swann-v-charlotte-mecklenburg-board-of-education-memorandum-of-james-e-swann. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I

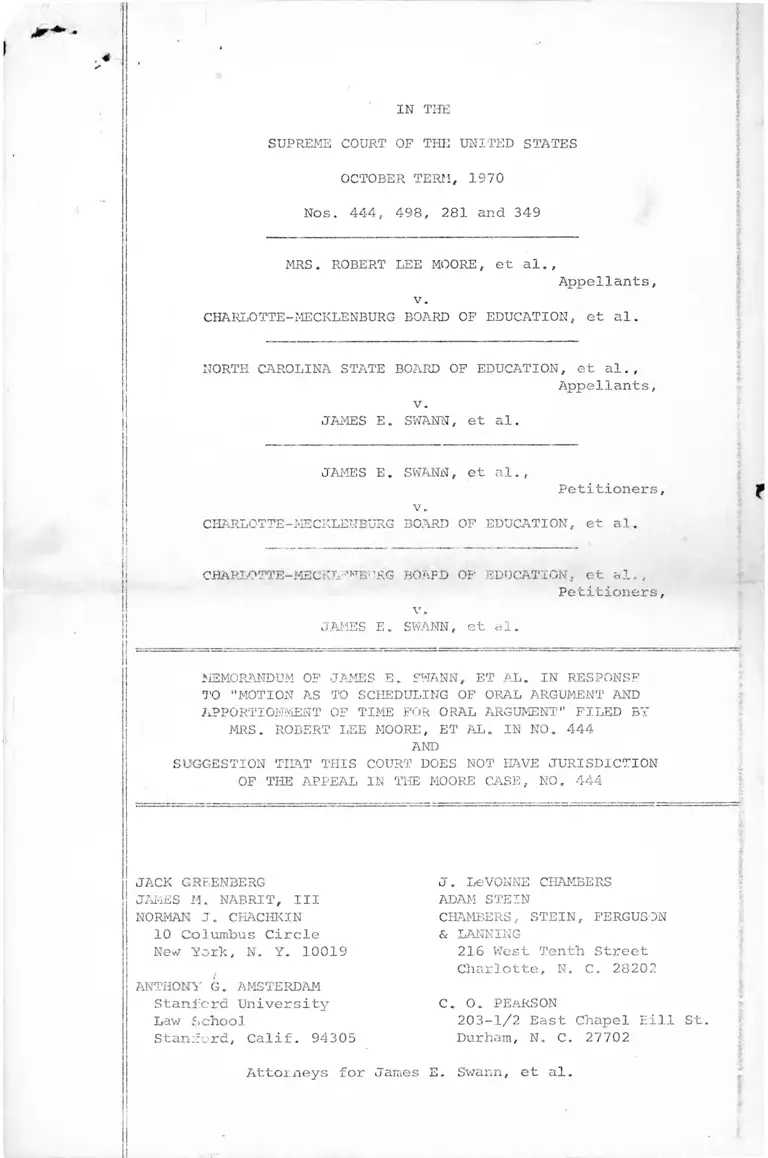

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1970

Nos. 444, 498, 281 and 349

MRS. ROBERT LEE MOORE, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

CHARLOTTE-MECKLENBURG BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.

NORTH CAROLINA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

JAMES E. SWANN, et al.

JAMES E. SWANN, et al.,

Petitioners, ^

v.

CHARLOTTE-MECKLENBURG BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.jI

CHA RLO TT E - ME C K L■ RG BOAFD OF EDUCATION, et al. ,

Petitioners,

v-JAMES E. SWANN, et al.i■

i

MEMORANDUM OF JAMES E. SWANN, ET AL. IN RESPONSE

TO "MOTION AS TO SCHEDULING OF ORAL ARGUMENT AND

APPORTIONMENT OF TIME FOR ORAL ARGUMENT" FILED BY

MRS. ROBERT LEE MOORE, ET AL. IN NO. 444

AND

SUGGESTION TILAT THIS COURT DOES NOT HAVE JURISDICTION

OF THE APPEAL IN THE MOORE CASE, NO. 444

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

I NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

Stanford University

Lav/ School

Stanford, Calif. 94305

J. LeVONNE CHAMBERS

AMAM STEIN

CHAMBERS, STEIN, FERGUSON

& BANNING

216 WTest Tenth Street

Charlotte, N. C. 28202

C. O. PEARSON

203-1/2 East Chapel Bill St.

Durham, N. C. 27702

Attorneys for James E. Swann, et al.

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1970

Nos. 444, 498, 281 and 349

MRS. ROBERT LEE MOORE, et al..

Appellants,

v.

CHARLOTTE-MECKLENBURG BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al,

NORTH CAROLINA STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

JAMES E. SWANN, et al.

JAMES E. SWANN, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

CHARLOTTE-MECKLENBURG BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.

CHARLOTTE-MECKLENBURG BOARD OF EDUCATION, et al.,

Petitioners,

v.

JAMES E. SWANN, et al.

MEMORANDUM OF JAMES E. SWANN, ET AL. IN RESPONSE

TO "MOTION AS TO SCHEDULING OF ORAL ARGUMENT AND

APPORTIONMENT OF TIME FOR ORAL ARGUMENT" FILED BY

MRS. ROBERT LEE MOORE, ET AL. IN NO. 444

AND

SUGGESTION THAT THIS COURT DOES NOT HAVE JURISDICTION

OF THE APPEAL IN THE MOORE CASE, NO. 444

James E. Swann, (it al. , by their attorneys, respectfully

submit the following memorandum in response to the motion filed

by the appellants Moore, et al. in No. 444, requesting that this

Court consolidate for argument, cases Nos. 281, 349, 444 and 498,

and permit the appellants Moore, et al. to present argument first

and to be allotted time equal to that of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education and the original plaintiffs, Swann, et al.

We oppose the motion on the grounds that:

1. Moore v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

No. 444, O.T. 1970, is a feigned or collusive suit in which there

are no parties asserting adverse or antagonistic claims and there

is no "case or controversy" as required by Article III of the

Constitution.

2. Since the Moore case, No. 444, is not a truly adversary

proceeding, no party has called the Court's attention to the

fact that very probably this Court has no jurisdiction of the

direct appeal under 28 U.S.C. § 1253 because the case was not

required by any statute to be heard by a three-judge district

court.

3. The Moore case, No. 444, involves no substantial ques

tions, as revealed by Appellants' Brief in that casq which makes

an entirely inadmissible effort to collaterally attack the judg

ments of the single district judge and of the Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit in the case of Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenburg Board of Education, No. 281, O.T. 1970, by using as

a vehicle a suit in which the Negro plaintiffs Swann, et al. are

not even named as parties.

I.

Statement of the Case

Proceedings in Moore v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of

Education, No. 444, October Term, 1970.

Unlike the other three cases now pending here involving the

desegregation of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg public schools—

- 2 -

I

Nos. 281, 349 and 498--all of which began as original.actions in

the United States District Court, the Moore case began in a

North Carolina state court. Its beginning was unusual to say the

least. The complaint was filed in the Superior Court of

Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, and an ex parte restraining

order was immediately issued by Judge Frank W. Snepp at 10:16

p.m. on Sunday night, February 22, 1970. (See A. 3-8, complaint;

A. 19, restraining order; A. 31 with respect to filing on Sunday

1/night).

At tie time the Moore case was filed and the state court

injunction issued, the Swann case had been in litigation in the

United States District Court for the Western District of North

Carolina for nearly five years. The full history of the Swann

case is set forth in Petitioners' Brief in Swann, No. 281, O.T.

1970 on file in this Court. Two weeks before the filing of

Moore the district judge in the Swann case had issued a desegre

gation order requiring implementation of a plan to desegregate

the schools during the then current school semester. That order

of February 5, 1970, appears at 311 F. Sujyp. 205 (W.D. N.C.

1970). On February 20, 1970, the district judge in Swann

requested that a three-judge court be convened to consider the

Swann plaintiffs' application for injunctive relief to restrain

jcertain state officials and the local school board from enforcing I

the North Carolina anti-bussing law (N.C. Gen. Stats, section

115-176.1) on the ground that it violated the Fourteenth Amend

ment. The Swann plaintiffs had also requested an injunction to

—

1/ Citations are to the Appendix in No. 444 "(A. )" unless

otherwise indicated as citations to the Appendix in No. 281 (A.

No. 281, p.___) .

3

stay another suit filed in the North Carolina scate court— Harris

v. self— by some of the same counsel representing the Moots

plaintiffs. The resident federal district judge on February 20

requested that this matter also be referred to the requested

three-judge court stating that the practical effect of the state

court injunctions obtained in Harris v. Self "may be to delay or

defeat compliance with the orders of this United States Crart"

(A. No. 281, pp. 845a-847a).

Against this background, the Moore complaint was filei late

on a Sunday night. The complaint was brought as a class artion

on behalf of parents and children of the district naming as

defendants only the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education and

the Superintendent of Schools. The complaint alleged that the

school system was already a racially unitary school system in

compliance with Brown v. Board of Education, but that the 5oard

and Superintendent were "under pressure of a Court directive --

about to implement" a plan under which pupils would be assigned

on the basis of their race and color. It was alleged that this

action the board was about to take under order of the federal

district court violated the rights of the Moore plaintiffsunder

the Fourteenth Amendment, the North Carolina Constitution, sec

tions 401(b) and 407(a) (2) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42

U.S.C. 2000c(b), and 42 U.S.C. 2000c-6(a)), and N.C. Gen. Stats,

section 115-17 6.1. The theory of the complaint was that tee

;

desegregation plan ordered by the federal district court violated;

the requirement of the Brown case that admission to public

schools be non-racial by taking race into consideration in

4

*

accomplishing desegregation of the schools. The Superior Court

«

of Mecklenburg County was asked to thus restrain the school

authorities in Charlotte-Mecklenburg from carrying out the deseg

regation plan ordered by the United States District Court on

February 5, 1970. The complaint prayed only for an order:

... restraining and enjoining the defendants from

instituting or implementing or putting into opera

tion or effect, or expending any public funds upon,

any plan or program under which the children named

above, or any children in the City of Charlotte

or Mecklenburg County are denied access to any

Charlotte-Mecklenburg public school because of

their race or color or are compelled to attend

any prescribed Charlotte-Mecklenburg public

school because of their race or color.

The complaint made no request for an injunction restraining the

enforcement of any statute, either state or federal.

As we have indicated, at 10:16 p.m. on Sunday, February 22,

Superior Court Judge Snepp issued an injunction in precisely the

terms requested by the Moore plaintiffs as quoted above (A. 19-

20) .

The school board reacted by deciding to obey the injunction

by Judge Snepp. Judge McMillan wrote that:

On Friday, February 27, 1970, the defendant

Board of Education had a meeting. Without any

inquiry of this court, the Board staff were

instructed to comply with the state court order

and to stop work on compliance with the order

previously entered by this Court (A. 31).

Also on February 27, the board filed a petition removing

5the Moore case to the federal district court. The removal peti- j

tion alleges that the case was removable because the federal

court "has original jurisdiction, in that rights or claims of

rights arising out of the Constitution and lews of the United

5

States, statutes of the United States and other rights are allegsd

in the complaint ..." (A. 21). Immediately and on the same date

— February 27, 1970---the Swann plaintiffs moved in that case for

an order adding the Moore plaintiffs, their attorneys, Messrs.

Booe and Blakeney, and Judge Snepp as defendants in the Swann

case, and for an order restraining them from taking any further

proceedings in the Moore case or taking any further steps to

frustrate the orders in the Swann case. The Swann plaintiffs

also moved for a temporary restraining order against these par

ties and the school board and that the school board be held in

civil contempt for its action in directing the school staff not

to carry out the district court's desegregation orders.

On February 28, all counsel were notified that a hearing

would be held in the federal district court on March 2 on

motions to set aside the effect of Judge Snepp1s order. Coun

sel for plaintiffs in the Moore case did not appear, but sent

word through secretaries by telephone that they were occupied

elsewhere" (A. 31).

On March 2, 1970, the school board filed a pleading with

the district court asserting that the order of Judge Snepp con

flicted with the district court orders and placed the board in a

dilemma, that the constitutionality of the North Carolina anti

bussing lav and certain provisions of the Civil Rights Act cf

1964 was involved, and requested a three-judge court to pass on

the case. On the same day, March ^, the Moore plaintiffs al̂ >o

filed a motion in the district court seeking an injunction. This

motion asserted that the school board might be deemed authorized

- 6 -

to implement the desegregation plan ordered by the district court

under a proviso in the North Carolina anti-bussing law which

states that school boards may assign a pupil outside his attend

ance zone "for any other reason which the board of education in

its sole discretion deems sufficient. " The Moore plaintiffs

prayed for an order enjoining the board from enforcing this pro

viso on the ground that the proviso "as thus applied and imple

mented is unconstitutional," and asked for the convening of a

statutory three-judge court. There was no request that the com

plaint be amended..

On March 6, the district court entered an order (A. 31-33)

which ruled that the order of Judge Snepp was "suspended and held

in abeyance and of no force and effect pending the final determi

nation by a three-judge court or by the Supreme Court of the

issues which will be presented to the three-judge court on March

24, 1970" (A. 32), and that the Moore case be referred to the

three-judge court which was scheduled to hear the Swann case on

March 24. Subsequently, the district judge formally requested a

three-judge court for the Moore case (A. 38) and such a court was

designated (A. 39).

On March 23, the school board filed an answer admitting all

of the allegations of the complaint. On March 23, the Moore,

plaintiffs served several requests for aclmissions on the school

board. The school board answered this request by admitting all

the matters requested by the Moore plaintiffs on the same day,

March 23, 1970. The various pleadings filed in the Moore case

were not served on the Swann plaintiffs.

- 7 -

When the case was heard by the three-judge court both

parties to the Moore case argued to the three-judge court that

the North Carolina anti-bussing law was valid and that the orders

of the single district judge in Swann should be set aside. The

hearing was consolidated with argument in the Swann case. On

April 29, 1970, the three-judge court filed its decision (A. 44-

62) now reported at 312 F. Supp. 503 (W.D. N.C. 1970). The court

held that the anti-bussing law was unconstitutional in violation

of the Fourteenth Amendment and the Supremacy Clause, in an

opinion written to cover both the Swann and Moore cases. Subse

quently, the final judgment of the three-judge court--also

entered in both the Swann and Moore cases— declared two sentences

in the anti-bussing law unconstitutional and provided that "all

parties" were enjoined "from enforcing, or seeking the enforce

ment of, the foregoing portion of the statute."

Three notices of appeal were filed from this final judgment

of June 22, 1970: an appeal by the Moore plaintiffs docketed

here as No. 444, an appeal by the North Carolina State Board of

Education (a party in the Swann case) docketed here as No. 498,

and an appeal by the Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education

which was never docketed in this Court. However, the Charlotte-

Mecklenburg board has taken two actions in this Court: (1) as

appellee in Moore the board has urged that this Court grant

review of the case; (2) the board has also made a motion seeking

to join in the appeal of the North Carolina State Board of

!

Education in No. 498.

8

The Moore Ca.se Involves No Adversary Parties

and Thus Presents No Case or Controversy.

The jurisdiction of this Court is restricted to cases and

controversies within the meaning of Article III of the Constitu

tion. Muskrat v. United States, 219 U.S. 346 (1911). In addi

II.

tion, this Court has developed a number of rules limiting its

consideration of constitutional contentions brought here for

decision. See, e.g., Ashwander v. Tennessee Valley Authority,

297 U.S. 288, 341, 346 (1936) (concurring opinion). One of the

principal requisites for constitutional adjudication is that there

be adverse claims— "an honest and actual antagonistic assertion

of rights by one individual against another." Chicago & G.T.R.C.

v. Weliman, 143 U.S. 339, 344, 345 (1892). The leading cases

involving the requirement of adversity are collected in Poe v.

Ullman, 367 U.S. 497, 505-507 (1961). Mr. Justice Frankfurter's

opinion in Poe states:

This principle was given early application and

has been recurringly enforced in the Court's

refusal to entertain cases which disclosed a want

of a truly adversary contest, of a collision of

actively asserted and differing claims. See,

e.g., Cleveland v. Chamberlain (US) 1 Black 419,

17 L ed 93; American Wood-Paper Co. v. Heft (US)

8 Wall 333, 19 L ed 378. Such cases may not be

"collusive" in the derogatory sense of Lord v.

Veazie (US) 8 How. 251, 12 L ed 1067— in the

sense of merely colorable disputes got up to

secure an advantageous ruling from the Court.

See South Spring Hill Gold Min. Co. v. Amador

Medean Gold Min. Co. 145 US 300, 301, 36 L ed 712,

12 S Ct 921. The Corrt has found unfit for adjudi

cation any cause that "is not in any real sense

adversary," that "does not assume the 'honest and

' actual antagonistic assertion of rights' to be

adjudicated— a safeguard essential to the integ

rity of the judicial process, and one which we

have held to be indispensable to adjudication

- 9 -

of constitutional questions by this Court."

United States v. Johnson, 319 U.S. 302, 303,

87 L ed 1413, 141:5, 63 S Ct 1075.

(367 U.S. at 505.)

It is entirely plain that there are no adverse claims being

asserted in the Moore case. Both the Moore appellants and the

appellees (the school board and school superintendent) have

argued at every stage of the proceeding that the court-ordered

desegregation plan was not constitutionally required, that it

conflicted with the state anti-bussing law, and that the latter

act was a valid exercise of state power. No party in the Moore

case argues any other viewpoint. Furthermore, it is obvious

that the parties are cooperating with each other. In Moore,

not only does the answer admit every allegation of the complaint,

but the school board responded to the Moore plaintiffs' Request

)| for Admissions bv admitting every fact asserted on the same day! i

the Request for Admissions was filed. The Moore plaintiffs now

join the school board in arguing against the decisions of the

single district judge and the Fourth Circuit in the Swann case,

even though they have never participated in Swann. It is

entirely plain that the parties to the Moore case assert no

adverse and antagonistic claims. This lack of adversity is

underlined if one contemplates the problem of determining which

partv obtained relief in the Moore case— who won? See our dis-

I| cussion of this in Part III, infra.

This Court should apply the rule that it "will not pass upon

the constitutionality of legislation in a suit which is not adver-

l

sary ... or in which there is no actual antagonistic assertion

- 10 -

L

of rights ... . " Congress of Industrial Organizations .v.

McAdorv. 325 U.S. 475 (1945), and cases cited. Application of

such a rule is all the more appropriate in this case since all

substantive claims that might appropriately be presented in

Moore are before this Court in the appeal filed by the North

Carolina State Board of Education, No. 498, where the parties

do have adverse interests.

/

11

Ill

This Cou3.~t Does Not Have Jurisdiction Of

The Mooro Case On Direct Appeal Under 28

U.S.C. § 1253 Because The Case Was Not

Required To Be Heard By A Three-Judge

District Court.

Although we have some serious doubts about the matter, for

the purposes of this discussion only we assume that the district

court had federal jurisdiction over the Moore case and that the

matter was properly removed to that court from the state court.

We believe that the jurisdiction of the single-judge district

court presents substantial arguable questions; they will not be

argued in the Moore case because as we have noted above there

are no adverse interests represented. The issues are discussed

_2yin the footnote below.

2/ The removal petition was apparently intended to invoke 28

U.S.C. §1441 permitting removal of actions of which the district

courts have original jurisdiction. Under §1441 removal may be had

only where the plaintiff states a claim over which the district

court would have jurisdiction. The complaint in the Moore case

does not state a claim within the "federal question" jurisdiction

of the district court (28 U.S.C. §1331) because there is no allega

tion that the matter in controversy exceeds the sun; or value of

$10,000. Further there has been no finding or proof of the juris

dictional amount. (And of course the plaintiffs may not aggregate |

their claims for purpose of making up the amount.) There is no

jurisdiction under any provisions such as diversity, Admiralty,

Bankruptcy etc. (28 U.S.C. §1332,§1333,§1334). Original juris

diction might also be invoked under "civil rights" jurisdiction

28 U.S.C. §1343(3) but the Moore complaint fails to make out such

a claim. Although the Moore plaintiffs do assert in their complaint

that the school board is violating their Fourteenth Amendment j

rights, there is probably no sufficient allegation that the board I

is depriving the j/laintiffs of rights "under color of State law,

statute, ordinance, regulation, custom or usage.” There is no

sufficient color of state law allegation because the Moore complaint

specifically alleges that the school board was acting under the

compulsion of the federal court orders rather than under any state;

lav/. I

There is a possibility that the case might have been properly

removable under the civil rights removal statute, 28 U.S.C. §1443VU} .

That provision permits removal of actions commenced in a state

court "For any act under color of authority derived from any law j

providing for equal rights, or for refusing to do any act on the j

ground that it would be inconsistent witli such law." It might

have been asserted in the removal petition that the board was

being sued for obeying a federal court order issued in a case

12

This Court has jurisdiction over direct appeals from orders

granting or denying an injunction "in any civil action, suit or

proceeding required by any Act of Congress to be heard and deter

mined by a district court of three judges." 28 U.S.C. §1253.

Under Section 1253 a direct appeal is permissible only where

a three-judge court is required and not merely where three-judges

actually decide a case. Phillips v. United States, 312 U.S. 246

(1941); Swift & Co. v. Wickham, 382 U.S. Ill (1965).

A three-judge court was not required in the Moore case

by either 28 U.S.C. Section 2281 or 2282. With respect to Section

2282 it is plain that the complaint did not seek any injunction

against "any Act of Congress for repugnance to the Constitution

of the United States." On the contrary the complaint asserted

that the only federal statute mentioned — the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 — supported the plaintiffs' claims. This Court's

decision in Kennedy v. Mendoza-Martinez, 372 U.S. 144 (1963) makes

it plain that a three-judge court is required only where an in

junction against a federal statute is sought. It is not enough

that rhe validity of a federal law or policy be merely implicated

in the case if there is no real request for an injunction against

the federal statute. Thus it is immaterial for jurisdictional

purposes that the school board has argued (A. 26-30) that the

district court desegregation order in the Swann case can be

upheld only if the provisions of the 1964 Civil Rights Act are

declared unconstitutional. The point is that neither party ever

sought any such injunction. Both parties attacked the district

court's desegregation order relying on the state and federal

statutes.

2 / cont'd.

brought under "a law providing for equal rights" — i.e., 42 U.S.

C. §1983 is the basis for Swann — and thus the case was removable

under §1443(2).

13 -

The school board's answer sought no injunction but merely

dismissal of the case. The board's application for an injunctive

order (A. 26) does; not indicate who it is that the board seeks

to enjoin. The district court interpreted it as a request that

the state court restraining order be dissolved. Even if it is

construed as a request for an injunction against the Moore

plaintiffs seeking to enforce the anti-busing act it would not

be the basis for a three-judge court because Moore, et al., are

not state officers, and thus the third requisite stated above is

not met.

The requisites for a three-judge court are not met by the

relief ultimately granted by the district court. That court in

dicated in its opinion that it would grant only a declaratory

judgment (A. 61) and would deny injunctive relief. Later that

portion of the opinion was withdrawn after the Court exchanged

correspondence with all counsel seeking their views with respect

to whether a direct appeal could be taken from the declaratory

judgment. This Court has settled that the declaration alone

does not support a direct appeal. Rockefeller v. Catholic

Medical Center, 397 U.S. 820 (1970) and Mitchell v. Donovan,

39C U.S. 427 (1970). The Court below finally entered a general

injunction stating merely that "All parties are hereby enjoined

from enforcing, or seeking the enforcement of, the foregoing

portion of the statute." (A. 65). This order was entered to I

apply to both Moore and Swann. As applied to Moore it is ob

viously an order against the Moore plaintiffs, who are not state

officers, and thus the order does not require a three-judge court.

The order cannot reasonably be construed as an injunction against»

the school board in the Moore case, forthe board could not obtain ;i

an injunction against itself and the Moore plaintiffs never

sought any such order against the school board. One party must

15

have won the Moore case. Apparently the prevailing party in

Moore was the school board. Of course the board was simultaneous

ly enjoined in the Swann case at the behest of Swann et al. and

directed to carry out the desegregation order without regard to

the anti-busing law. (The difficulty in ascertaining who — if *

anyone — won the Moore case nicely underlines the point we have

made about lack of adverse parties.)

Finally the Moore plaintiffs'application for an injunctive

order filed in the district court on March 2, 1970 (A. 23-25) does

not meet the requisites for a three-judge court. This motion

is a rather curious document. In its first four paragraphs it

asserts that the state anti-busing law (N.C.Gen.Stat. §115-176,1)

'

provides that no pupils shall be excluded from or assigned to

any school on a racial basis; that this law is in harmony with

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) and 349 U.S.294

(1955); that the statute also contains a proviso authorizing a

school board to make assignments of pupils "in its sole discretion*;

and that the school board was planning to implement a desegregation

plan under which pupils will be assigned on the basis of race. Tht

fifth paragraph states:

;

"5. That it may be deemed that in such

actions, the defendants are authorized

and supported by the aforesaid proviso

in the aforesaid statute, which permits

them to assign and reassign school children

in their ‘sole discretion1; that in such

respect and in such application,however,

the said proviso conflicts with the united

States Constitution and specifically with

the previsions of the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution, as interpreted and ruled !

by the supreme Court of the United States in

the case of Brown v. Board of Education, re

ferred to above, 347 U.S. 483 and 349 U.S. 294.

(A.24).

16

It is entirely obvious upon examining this pleading that

the Moore plaintiffs' motion for injunctive relief against a

portion of the statute which the Moore plaintiffs rely upon in

their complaint is merely a forum shopping device in an effort

to get the case away from the resident district judge —

Judge McMillan — and before other judges. This is entirely

obvious on the face of the pleading and is confirmed by the

fact that the attorneys for the Moore plaintiffs made motions

seeking to get Judge McMillan recused or removed from the three

judge case. (See Appendix No. 281, docket sheets page 10,1a.)

The device is really transparent because the claim that the

proviso in the anti-busing law should be enjoined is not pressed

any further in the case. The only question presented by the

Appellant's Brief in this Court is that the board should have

Judge Snepp's state court injunction against the school board

j restored. And, of course that injunction was not against the

anti-busing law, but in purported reliance upon it.

However,., the court need not decide whether a transparent

forum shopping device such as the Moore motion for an injunction

against a portion of the anti-busing law would justify a three-

judge court if it stated a case requiring three judges. This

I motion does notrequir three judges because of the fourth and

fifth requisites listed above. The motion doesnot urge that the

proviso giving the board discretion to assign pupils is unconsti-

_3_/tutional, but only that the use of the statute will violate the

3/ An argument that the statutory provision giving boards

discretion to assign pupils was unconstitutional on its face

(and not in its use) would not be sufficiently substantial tc

require a three-judge court. Ex parte Poresky,290 U.S. 30(1933).

17

Brown case. Thus no three—~iudge court is required, under Ex Parte

Bransford, 310 U.S. 354, 361 (1940). It is also clear that the

motion complains only of local Charlotte—Mecklenburg use of

the discretion giving law and not of any statewide policy of

the statute. Thus no three-judge court is required under Griffin

v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, 377 U.S. 218,

227-228 (1964) .

I

18

IV.

The Moore Case Involves no Substantial Questions.

An examination of Appellants' Brief will reveal that the

Moore case presents no substantial questions. The greater por

tion of the brief consists of an effort to mount a collateral

attach on the decision of the Fourth Circuit and the single dis

trict judge ordering desegregation of the public schools. It is

entirely inappropriate and inadmissible that a state court pro

ceeding can be used to review the decision of a federal district

court as the Moore plaintiffs attempted. Bush v. Orleans Parish

School Board, 188 F. Supp. 916, 925 (E.D. La. I960), affirmed, 36

U.S. 569 (1961). They never attempted to intervene in the Swann

case in the district court or to file an amicus curiae brief.

Instead, they attempted to obstruct the district court order by

obtaining a late-Sunday-night ex parte injunction. These dis

reputable tactics merit strong condemnation. The power of the

dis trict court to protect itself against: such tactics is

undoubted. Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 187 F. Supp. 42

(E.D. La. 1960), affirmed, 365 U.S. 569 (1961); Thomason v.

Cooper, 254 F.2d 808 (8th Cir„ 1958); Meredith v. Fair, 328 F.2d

586 (5th Cir. 1952; en banc); 1A Moore's Federal Practice, 2319-

2320, 2614-2616; 28 U.S.C. § 2283.

The effort to relitigate Judge McMillan's desegregation

orders in the Mcore case is all the more inappropriate inasmuch

as the Negro plaintiffs who obtained the Swann desegregation

order after five years of litigation were not even named as par

ties to the Moore case, and could not participate in making the

record.

19

Finally, the decision of the three-judge court holding the

anti-bussing law unconstitutional is firmly grounded in this

Court's decisions. The case is plainly controlled by Green v.

County School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968), for

the reasons stated in the opinion below. The anti-bussing act

disables school boards from performing their affirmative duty to

dismantle dual systems and desegregate the schools. The Moore

plaintiffs' argument that it violates the Brown decision to con

sider race or utilize race in devising a desegregation plan is

obviously designed to prevent the dismantling of existing dual

systems. A board rendered "blind" to the race of its pupils is

disabled from dismantling a dual segregated system and accomplish

ing desegregation. The district court found that fifty-five

percent of the public school pupils in North Carolina ride school

buses every day and that busing was extensive in Charlotte (A.

No. 281, pp. 1198a-1220a). The attempt to forbid the use of

these extensive transportation facilities in any circumstances

to accomplish the desegregation of the schools is simply in the

teeth of the Brown and Green cases. The appeal presents no sub

stantial question and should be dismissed under the doctrine of

Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U.S. 31 (1962).

20

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, it is suggested that this Court

lacks jurisdiction over the Moore case and that the Motion to

Consolidate that case for argument with the other cases involv

ing Charlotte-Mecklenburg and allot additional time for argument

by Moore> et al. should be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, N. Y. 10019

J. LeVONNE CHAMBERS

ADAM STEIN

CHAMBERS, STEIN, FERGUSON & LANNING

216 West Tenth Street

Charlotte, N. C. 28202

C. O. PEARSON

203-1/2 East Chapel Hill St.

Durham, North Carolina 27702

ANTHONY G. AMSTERDAM

Stanford University

Law School

Stanford, Calif. 94305

Attorneys for James E. Swann, et al.

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that I have this 1st day of October,

1970, served copies of the foregoing Memorandum of James E.

Swann, et al. on attorneys for all parties named >>erein, by

21

United States mail, air mail special delivery, postage prepaid,

addressed to the following:

Whiteford S. Blakeney, Esq.

North Carolina National Bank

Building

Charlotte, N. C.

William H. Booe, Esq.

Law Building

Charlotte, N. C.

William J. Waggoner, Esq.

Weinstein, Waggoner, Sturges,

Odom and Bigger

1100 Barringer Office Tower

428 North Tryon Street

Charlotte, N. C. 28202

Benjamin S. Horack, Esq.

Ervin, Horack and McCartha

806 East Trade Street

Charlotte, N. C.

Hon. Robert B. Morgan

Attorney General of North

Carolina

Justice Building

Post Office Box 629

Raleigh, N. C. 27602

Hon. Ralph Moody

Deputy Attorney General

Justice Building

Post Office Box 629

Raleigh, N. C. 27602

Hon. Andrew A. Vanore, Jr.

Assistant Attorney General

Justice Building

Post Office Box 629

Raleigh, N. C. 27602

Hon. Erwin N. Griswold

Soli.citor General of the U. S.

Department of Justice

Washington, D. C. 20530

James M. Nabrit, III

Attorney for James E. Swann, et ah