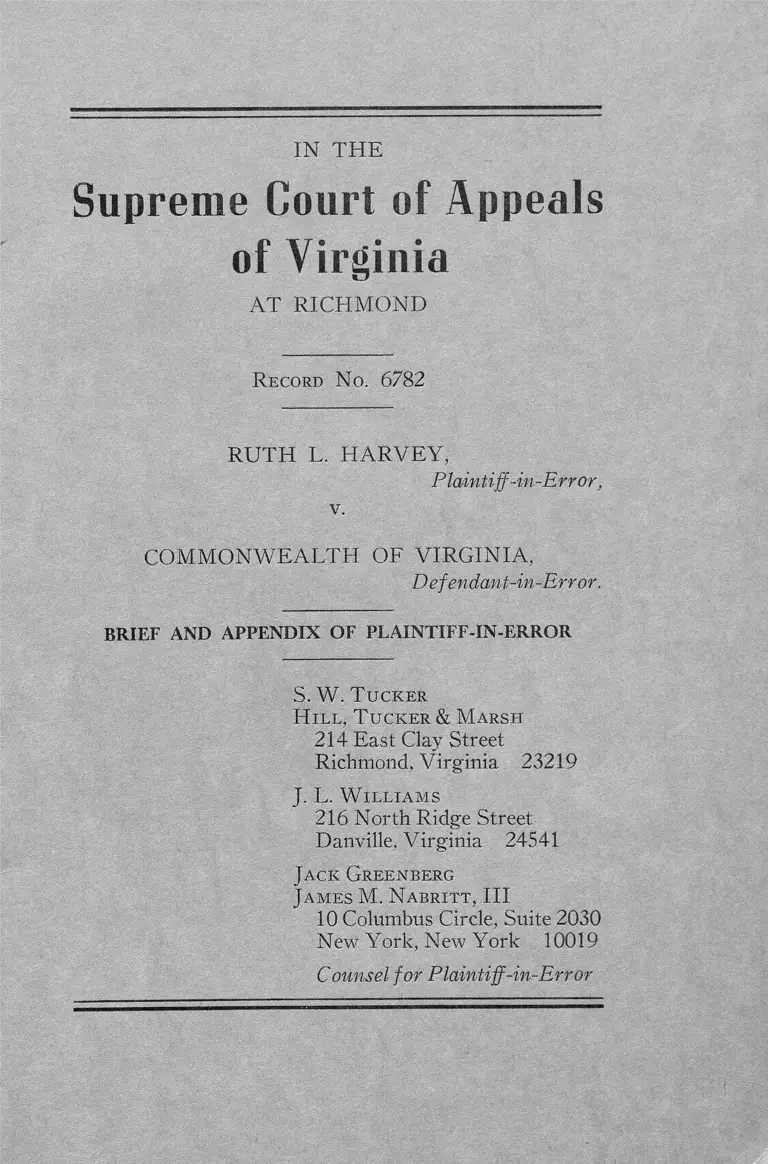

Harvey v. Commonwealth Brief and Appendix of Plaintiff-in-Error

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Harvey v. Commonwealth Brief and Appendix of Plaintiff-in-Error, 1967. 383d7a9b-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/53fef719-9b53-456a-aab1-70c7d0987e6a/harvey-v-commonwealth-brief-and-appendix-of-plaintiff-in-error. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

IN T H E

Supreme Court of Appeals

of Virginia

AT RICHMOND

R ecord N o. 6782

RUTH L. HARVEY,

Plaintiff-in-Err or.

v.

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA,

Defendant-in-Err or.

BRIEF AND APPENDIX OF PLAINTIFF-IN-ERROR

S. W . T u ck er

H il l , T u c k e r & M arsh

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

J. L. W il l ia m s

216 North Ridge Street

Danville, Virginia 24541

J ack Greenberg

J a m es M. N a b r it t , III

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Plaintiff-in-Err or

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

S ta tem en t Of T h e M ateria l P roceedings I n T h e L ower

Court ............. -................- ............................... -........................ -............. 1

S t a t e m e n t O f T h e F a c t s ................................................................... 2

T h e A s sig n m en ts O f E rror ............................................................... 5

T h e Q u estio n s P r e s e n t e d ................................................................... 6

A r g u m en t ........................ 6

I. Petitioner Was Denied Due Process Of Law In Viola

tion Of The Fourteenth Amendment.......... .... ............... 6

II. There Was No Willful Purpose Of Deceiving The Court

Or Any Other Misconduct Constituting Contempt----- 12

Co n c lu sio n ............................................................................... 13

A ppe n d ix

I. Letter from Commonwealth’s Attorney.......................App. 1

II. Excerpts from Transcript, pp. 1, 2, 7 and 8 ...............App. 2

III. Excerpts from Transcript, pp. 10, 212 & 213...........App. 6

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases

Baines, et al. v. City of Danville (Section II) , 337 F. 2d 579

(4th Cir. 1964, remand affirmed 384 U.S. 890, 16 L. ed 2d

996, 86 S.Ct. 1915 (1966) ...................................................... 2

Brown, R. Jess, In the Matter of, 346 F. 2d 903 (5th Cir. 1965) 12

Cooke v. United States, 267 U.S. 517, 45 S.Ct. 390, 67 L. ed

767 (1925) ................................................................................ 7

Gault, In re, 387 U.S. 1, 18 L. ed 2d 527 87 S. Ct.

Page

. . . 11

Higgenbotham v. Commonwealth, 206 Va. 291, 142 S.E. 2d

746 (1965) ................................................................................ 10

Holt, L. W., et al. v. Commonwealth of Virginia, 381 U.S. 131,

14 L. ed 2d 290, 85 S.Ct. 1375 (1965) ................................. 6

Oliver, In re, 333 U.S. 257, 68 S.Ct. 499, 92 L. ed. 682 (1948) 7

Ruffalo, John, Jr., Petitioner, In the Matter o f,.....U.S........., 36

U.S. Law Week 4284 (No. 73 October Term 1967) ......... 10

Sacher v. United States, 343 U.S. 1, 96 L. ed 1341, 72 S.Ct.

451 (1952) ............................................................ ................ . 11

Thomas, et al. v. City of Danville, 207 Va. 656, 152 S.E. 2d 265 3

Wise v. Commonwealth, 97 Va. 779, 34 S.E. 453 (1899) ......... 10

Other Authorities

Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended, Section 18.1-292 ............... 10

17 C.J.S. 66, Section 25(b) Contempt, By Attorney................... 13

IN T H E

Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

AT RICHMOND

R ecord N o. 6782

RUTH L. HARVEY,

v.

Plaintiff -in-Err or,

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA,

Defendant-in-Error.

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFF-IN-ERROR

STATEMENT OF THE MATERIAL PROCEEDINGS

IN THE LOWER COURT

Insofar as the petitioner knew, or had reason to know,

that any charge or accusation against her was pending,

the proceedings in the lower court consisted only of a

colloquy in open court on December 20, 1966 (R. 17,

18) which began with this remark by the Court:

“Miss Harvey, the Court is of the belief that you’ve

deceived the court here about Leonard Holt” ;

included these further remarks by the court:

2

“You misled the court about representing him. * * *

And after hearing the witness, Mr. Womack, testify

about it, I ’m satisfied you were not frank with the

court about it” ;

and, but for the petitioner’s subsequent notation of an

appeal, concluded with this remark by the court:

“I don’t think you were frank with the court. The

court feels you are in contempt of court and fines

you $25.00.”

Exceptions to the action of the court were filed with

the clerk on January 9, 1967 and noted by the court in

its order entered February 20,1967.

STATEMENT OF FACTS

I

Leonard Winston Holt, Esquire, was one of the per

sons who had been the subjects of more than 371 arrests

made in June, July, August and September of 1963 for

alleged violations of the temporary injunction and re

straining order of the Corporation Court of the City of

Danville entered in the case of City of Danville v. Law

rence George Campbell, et al. Prosecution of these cases

was delayed by reason of their removal to the United

States District Court for the Western District of Vir

ginia (see Baines, et al. v. City of Danville (Section II),

337 F. 2d 579 (4th Cir. 1964), remand affirmed 384 U.S.

890,16Led. 2d996, 86S.Ct. 1915 (1966)).

Meanwhile these cases were dropped from, the Corpora

tion Court’s active docket and were in such inactive

status on November 21, 1966 when this Court heard

3

arguments on an appeal from said injunction as made

perpetual ( Thomas, et al. v. City of Danville, 207 Va.

656, 152 S.E. 2d 265).

These prosecutions for violations of the temporary in

junction and restraining order were not mentioned when

the docket was called and criminal cases were regularly

set for trial or continued at the first day of the November

1966 Term of the Corporation Court, i.e. on November

6, 1966. It then was, and had been, the practice of said

Corporation Court that pending criminal cases not set

for trial at the November Term stood continued to the

January Term next following, the December Terms be

ing reserved for civil cases. However, on or subsequent

to November 11, 1966, the Honorable A. M. Aiken noti

fied counsel that these cases would be tried in December

1966; and by letter of December 7, copy of which is

herewith exhibited as Appendix No. 1, the Attorney for

the Commonwealth notified the petitioner and her as

sociate of the date (December 13, 14, 15, 16 or 19) on

which each of the 371 cases would be tried.

Of all of the lawyers who in 1963 were engaged in the

defense of persons arrested for participating in the racial

protest demonstrations, only two were practicing in Dan

ville in 1966; namely, Ruth L. Harvey (petitioner herein)

and J. L. Williams, Esquire. Unaided, except by her secre

tary, the petitioner undertook the task of locating and giv

ing appropriate notice to the several defendants, a great

number of whom for varying reasons were then far re

moved from. Danville. The court’s recognition of the diffi

culties involved in this undertaking was expressed during

a conference in chambers on December 13, 1966 which is

recorded in a duly certified transcript of the testimony

and incidents of the trial of Irwin Christopher Bethel

4

and others,1 a copy of pages 1, 2, 7 and 8 of which is

herewith exhibited as Appendix No. 2.

The court and all concerned counsel had initially as

sumed that all of the persons charged with violations of

the injunction were and would be represented by Mr.

Williams and Miss Harvey.

II

Upon departing from Danville in 1963, Mr. Holt in

dicated to the petitioner that she was to handle his case

(R. 18). On December 7, 1966 when the cases were set

for trial, the petitioner’s information was that Mr. Holt

was in Washington, D. C. Thereafter, some person at

his house in Washington, D. C. had told the petitioner (R.

10) and/or the petitioner’s secretary (R. 17, 18) that

Mr. Holt would be in court on December 20. Accordingly,

on December 15, when the clerk called “Leonard Winston

Holt,” the petitioner indicated to the court that Mr.

Holt would be there on December 20 and was understood

by the court as representing that she was “expecting him

here the 20th” (R. 6). It was then agreed that evidence

against him. would be heard at the same time as the

evidence against the others with whom he had allegedly

participated in a demonstration, in order to serve the

“possibility that later on . . . they may stipulate that the

evidence that had been heard on this occasion can be used

with reference to his matter” (R. 7).

On the following day (December 16) and when both

Mr. Williams and the petitioner were in court, one Walter

1 Petitions for writs of error in these cases have been pending

since June 20, 1967.

5

Link was permitted to enter a plea of guilty to a charge of

violating the injunction on June IS, 1963 and to do so

without advice or assistance of counsel, although he quite

clearly seemed to have expected that the advice and serv

ices of a lawyer would have been available to him. Upon

his disavowal of any sense of contrition,2 Walter Link

was sentenced identically as other participants who were

not leaders had been sentenced ; i.e., ten days on the City

Farm, eight days suspended, and a fine of twenty dollars

(R. 7,8).

Having had no contact with L. W. Holt, Esquire, for

three years, except through members of his family (R.

17, 18) and, hence, being unsure of their authority to

“stipulate anything as far as Mr. Holt is concerned”

(R. 10), the petitioner and Mr. Williams, on December

20, simply declined to represent L. W. Holt at his trial

then scheduled. However, when the court ruled that the

petitioner would not be released from her earlier entry

of appearance for L. W. Holt (R. 16) she and Mr.

Williams, as counsel for the defendant Holt, then stipu

lated that the testimony previously heard would be con

sidered as evidence against Holt; and thereupon he was

convicted of violating the injunction (R. 16, 17).

THE ASSIGNMENTS OF ERROR

1. The court erred and violated the Fourteenth

Amendment requirements of due process by not giving

2 The expectation of the Court that some show of penitence might

be made by some of the defendants had been demonstrated at the

above-mentioned December 13-14 trial of Irving Christopher Bethel

and others, a copy of pages 10, 212 and 213 of the transcript of

which is herewith exhibited as Appendix No. 3.

6

the respondent notice of a charge or citation against her

and a fair opportunity, with such charge or citation in

mind, to cross-examine the witness on whose testimony

the court relied and to present evidence in her own de

fense.

2. The court erred in finding that the respondent had

a willful purpose of deceiving the court.

3. The court erred in finding that there was mis

conduct reflecting improperly on the dignity of the court

or misconduct embarrassing the court or otherwise tend

ing to obstruct, prevent or embarrass the due administra

tion of justice.

THE QUESTIONS PRESENTED

I

Whether Appellant Could Be Punished Summarily?

II

Whether Appellant Could Be Punished At All ?

ARGUMENT

I

Petitioner Was Denied Due Process Of Law In Violation Of

The Fourteenth Amendment

The first assignment of error is to the denial of notice

of a charge or citation and a fair opportunity to be heard.

In this regard the petitioner’s case is singularly similar

to L. W. Holt, et al. v. Commonwealth of Virginia, 381

U.S. 131, 14 L. Ed. 2d 290, 85 S. Ct. 1375 (1965) where,

as here, “it [was] not charged that petitioners . . . dis

7

obeyed any valid court order, talked loudly, acted boister

ously, or attempted to prevent the judge or any other of

ficer of the court from carrying on his court duties” (381

U.S.at 136).

The case of In re Oliver, 333 U.S. 257, 68 S. Ct. 499,

92 L. Ed. 682 (1948), clearly articulates the Fourteenth

Amendment due process right asserted in the first ex

ception (R. 3). In reversing the Michigan court’s denial

of habeas corpus sought on behalf of a witness who was

summarily charged with, convicted of, and jailed for, an

alleged contempt of court, the Supreme Court held—

. , that failure to afford the petitioner a reasonable

opportunity to defend himself against the charge of

false and evasive swearing was a denial of due

process of law. A person’s right to reasonable notice

of a charge against him., and an opportunity to be

heard in his defense—a right to his day in court—

are basic in our system of jurisprudence ; and these

rights include, as a minimum, a right to examine the

witnesses against him, to offer testimony, and to be

represented by counsel.” (333 U.S., at 273)

Refering to its earlier decision in Cooke v. United States,

267 U.S. 517, 45 S. Ct. 390, 67 L. ed 767 (1925), the

Court said

“. . . that knowledge acquired from the testimony of

others, or even from the confession of the accused,

would not justify conviction without a trial in which

there was an opportunity or defense.” (333 U.S., at

275)

“Except for a narrowly limited category of contempts,

due process of law as explained in the Cooke case

8

requires that one charged with contempt of court be

advised of the charges against him, have a reason

able opportunity to meet them by way of defense or

explanation, have the right to be represented by

counsel, and have a chance to testify and call other

witnesses in his behalf, either by way of defense or

explanation. The narrow exception to these due

process requirements includes only charges of mis

conduct, in open court, in the presence of the judge,

which disturbs the court’s business, where all of the

essential elements of the misconduct are under the

eye of the court, are actually observed by the court,

and where immediate punishment is essential to pre

vent ‘demoralization of the court’s authority * * *

before the public.’ If some essential elements of

the offense are not personally observed by the judge,

so that he must depend upon statements made by

others for his knowledge about these essential ele

ments, due process requires, according to the Cooke

case, that the accused be accorded notice and a fair

hearing as above set out.” (333 U.S. at 275-6)

For the particulars of the supposed deception in the

instant case, we have this statement by the Court:

“You misled the Court about representing him.”

The occasion of the supposed deception is not as im

mediately apparent. However, the court did indicate that

the testimony of Mr. Womack supported its conclusion

that the petitioner had misled the court about representing

L. W. Holt. That testimony indicated that, prior to De

cember 20, the petitioner had acknowledged to Womack

that she represented Holt (R. 12) ; therefore it corrobo

rated her earlier statements to the court to that effect.

9

After hearing Mr. Womack’s testimony, the court ruled

that it could not release the petitioner from the repre

sentation of Mr. Leonard Holt. The court did not appoint

petitioner as counsel to defend Holt; it considered that

the petitioner had in fact accepted that responsibility and

had not thereafter been relieved. The conclusion of the

court on which the contempt conviction is based was that

the petitioner did mislead the court on December 20 when

she disavowed her authority and duty to represent Leon

ard Winston Holt.

It seems that such disavowal was made during the con

ference in chambers referred to on page 9 of the printed

record and was first stated in open court by the City

Attorney. In any event, nothing on the subject was stated

in open court by the respondent or her associate before

the court’s question which appears at the top of page 10

of the printed record, viz:

“* * * Now, Miss Harvey and Mr. Williams, you

told me several days ago here in Court that you

did represent Leonard Holt. Why is it now you say

you do not?”

The conclusion that the December 20 disavowal con

stituted the alleged contempt may be debatable. But the

reliance of the trial judge upon statements made by some

other person for some essential element of the alleged of

fense is beyond dispute.

“The Court: Miss Harvey, the Court is of the belief

that you’ve deceived the Court here about Leonard

Holt.

* * *

10

“And after hearing the witness, Mr. Womack, tes

tify about it, I’m satisfied you were not frank with

the Court about it.” (R. 17, 18)

Here the judge became “satisfied” after hearing a wit

ness testify in another proceeding. In Higgenbothlam v.

Commonwealth, 206 Va. 291, 142 S.E. 2d 746 (1965),

the judge “upon reflection” concluded that an attorney’s

conduct had been contumacious. In neither case was there

an open threat to the orderly procedure of the court or

flagrant defiance of the person and presence of the judge

before the public, threatening demoralization of the

court’s authority. As in the cited case, so here, “the judge

should have had a rule specifying the alleged contempt

uous acts served on the defendant, to be followed by a

full hearing in the matter, instead of exercising his dis

cretionary summary power under Code § 18.1-292.” At

the very least the plaintiff-in-error was entitled to an op

portunity to make an explanation as was done (and, on

appeal held satisfactory) in Wise v. Commonwealth, 97

Va. 779, 34SE453 (1899).

The April 8, 1968 opinion of the Supreme Court In the

Matter of John Ruffalo, Jr., Petitioner, ..... U.S.........

36 U.S. Law Week 4284 (No. 73 October Term, 1967)

accents these arguments. Reviewing a disbarment order

of the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Cir

cuit, the Court, speaking through Mr. Justice Douglas,

noted:

“ [T]he charge (No. 13) for which petitioner stands

disbarred was not in the original charges made

against him. It was only after both he and Orlando

had testified that this additional charge was added.

11

Thereafter, no additional evidence against petitioner

relating to charge No. 13 was taken. Rather, counsel

for the county bar association said:

‘We will stipulate that as far as we are con

cerned, the only facts that we will introduce in

support of Specification No. 13 are the state

ments that Mr. Ruffalo has made here in open

court and the testimony of Mike Orlando from

the witness stand. Those are the only facts we

have to support this Specification No. 13.'

* * *

“ [Petitioner had no notice that his employment of

Orlando would be considered a disbarment offense

until after both he and Orlando had testified at length

on all the material facts pertaining to this phase of

the case. As Judge Edwards, dissenting below, said,

‘Such procedural violation of due process would

never pass muster in any normal civil or criminal

litigation.’ 370 F. 2d, at 462.

“These are adversary proceedings of a quasi-criminal

nature. Cf. In re Gault, 387 U.S. 1, 33. The charge

must be known before the proceedings commence.

They become a trap when, after they are underway,

the charges are amended on the basis of testimony of

the accused. He can then be given no opportunity to

expunge the earlier statements and start afresh.

As in the cited case, so here: “The absence of fair notice

as to the reach of the . . . procedure and the precise na

ture of the charges deprived petitioner of procedural due

process.” As was well said by Mr. Justice Frankfurter,

dissenting in Sachet v. United States, 343 U.S. 1, 23, 36,

96 L. Ed 1341, 72 S.Ct. 451 (1952),

12

“Summary punishment of contempt is concededly an

exception to the requirements of Due Process. Ne

cessity dictates the departure. Necessity must bound

its limits.”

II

There Was No Willful Purpose Of Deceiving The Court Or

Any Other Misconduct Constituting Contempt

We assume no one would contend that the plaintiff-in

error’s earlier entry of appearance for Leonard W. Holt

was not made in good faith. The record indicates that

she was and had been relying on representations made

by persons at his Washington, D. C. address to her and/

or to her secretary that he would appear for trial. At some

subsequent time she learned that her messages had not

in fact been received by Holt and that the promise that

he would appear did not emanate from. him. Unpleasant

experiences of other civil rights lawyers suggested that

hers was an awkward situation. See, e.g., In the Matter

of R. Jess Brown, 346 F. 2d 903 (5th Cir. 1965).

On the other hand, however, the December 16 pro

ceedings in the case of Walter Link had served to demon

strate that the court did not indulge and take at face

value the assumption that the petitioner and Mr. Williams

represented all of the people who had been charged with

violating the injunction. In his explanation for not repre

senting L. W. Holt, Mr. Williams said that Mr. Holt

did not tell them “very definitely” to represent him, that

they were representing all of the people who had been

in touch, but that Mr. Holt did not so qualify (R. 10).

Later the petitioner said: “At the time Mr. Holt left

13

here . . . that was three years ago, he indicated that I

was to handle the case” (R. 18). Understandably the two

lawyers had different impressions as to what authority

in 1963 Holt gave to one in the absence of the other.

However, neither of them, showed an unwillingness to

defend Holt; they merely supposed that they were then

without authority (as in the case of Walter Link they

had felt themselves to be without authority) and, hence,

that they “could not stipulate anything as far as Mr, Holt

was concerned” (R. 10). Once the court had resolved

the question of authority, they defended him as they had

defended the others.

The general rule, as stated in 17 C.J.S. 66, Contempt

§ 25 (b) By Attorney, is :

“Misconduct by an attorney which reflects improper

ly on the dignity or authority of the court, or which

obstructs or tends to obstruct, prevent, or embarrass

the due administration of justice, constitutes con

tempt.”

Nothing in the conduct of the petitioner merits condemna

tion under this test. The trial of Leonard Winston Holt

was in no way obstructed. There was no interference

with any of the proceedings of the court.

CONCLUSION

There clearly was no necessity for summary punish

ment. Regard for procedural process would have afforded

opportunity for inquiry, explanation and understanding.

The petitioner’s doubt of her authority to represent Holt

required resolution but, under the circumstances, did not

14

merit censure. The judgment of conviction should be

reversed and the prosecution dismissed.

Respectfully submitted,

S. W. T u ck er

Of Counsel

S. W. T ucker

H il l , T u ck er & M arsh

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

J. L. W il l ia m s

216 North Ridge Street

Danville, Virginia 24541

J ack Greenberg

J a m es M. N a b r it , I I I

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Plaintiff-in-Error

A P P E N D I X

App. 1

Appendix No. 1

EUGENE A. LINK

ATTORNEY & COUNSELLOR AT LAW

D A N V ILLE, V IR G IN IA

M A SO N IC B U IL D IN G

December 7,1966

Miss Ruth Harvey, Attorney

453 South Main Street

Danville, Virginia

Dear Miss Harvey:

Re: Cases involving violation of

restraining order and temporary

injunction.

We have set down for trial all cases listed on Mr.

Tucker’s docket involving the following violations:

Cases 1 through 57 set for December 13, 1966.

Cases 58 through 134 set for December 14,1966.

Cases 135 through 231 set for December 15, 1966.

Cases 232 through 333 set for December 16, 1966.

Cases 334 through 371 set for December 19, 1966.

The Honorable A. M. Aiken, Judge, has notified me

that only the cases involving the temporary injunction

will be tried in December. I have therefore set out above,

the cases according to the docket, to be tried according to

the above dates.

I am giving you this information so that you will be in

position to notify your clients and have them in Court on

the dates scheduled.

App. 2

Yours very truly,

/ s / E u g e n e A. L in k

Eugene A. Link, Attorney for the

Commonwealth, for the City of

Danville, Virginia.

EAL :dml

cc: Mr. Jerry L. Williams, Attorney

216 North Ridge Street

Danville, Virginia

EXCERPTS FROM TRANSCRIPT

Appendix No. 2

[t r . P. 1]

VIRGINIA:

IN THE CORPORATION COURT OF DANVILLE,

COMMONWEALTH OF VIRGINIA )

)

V. )

)

IRVIN CHRISTOPHER BETHEL, )

LENDBURY BRADSHAW, )

HARRISON BROWN, JR., )

JAMES COBB, JR., )

JOHN ROLAND COLEMAN, )

LAWRENCE COLEMAN, )

ELLIS NEWTON DODSON, )

WILLIAM HAYWOOD INGRAM )

ROBERT JAMES LEWIS, )

MARGIE MABIN, )

HILDRETH GLENNELL McGHEE, )

ARCHIE LEE PETTY, )

HARVEY LEWIS POTEAT, )

LUVINIA PRITCHETT, )

App. 3

JIMMY RAY HAIRSTON.

WILLIAM HOWARD SCOTT,

PERCY WALTERS,

GEORGE ALBERT WATKINS

JAMES EDWARD W HIPPLE

VERNICE SMITH, and

RALPH FRANK WALTERS,

MELVIN WARNER,

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

The following constitutes a transcript of all of the oral

testimony and other incidents of trial in the above-styled

cause, before the Honorable A. M. Aiken, Judge of the

Corporation Court of the City of Danville, on December

13th and 14th 1966, wherein each of the above-named

defendants was tried on a charge of Violation of Tempo

rary Injunction and Restraining Order, and which was

electronically recorded.

[tr . p . 2]

PRESEN T:

Eugene A. Link, Esq.,

Danville, Virginia,

James A. H. Ferguson, Esq.,

Danville, Virginia,

For the Commonwealth

Ruth L. Harvey, Esq.,

Danville, Virginia,

J. L. Williams, Esq.,

Danville, Virginia,

S. W. Tucker, Esq.,

Emporia, Virginia,

For the Defendants.

App. 4

Each of the Defendants in person, with the exception of

Jimmy Ray Hairston.

* * *

[t r . p p . 7-8]

C h a m bers

* * * that a little. We have these cases set the 13th, that’s

today, the 14th, 15th, 16th and the 19th. We have them

set for those days.

Mr. Lin k : I think we ought to go on through the

rest of them, and, of course, see if they get here. Some

of them are on here two or three times. There are other

people who are not on here. I notice too, Judge, these

cases are not set on the docket according- to . . . ap

parently the arrest date and not according to the offense

date. So most of the relative dates we were going to try

these cases, I believe was 1 through 57 on the 13th.

J udge A ik e n : They are the ones set for today.

M r . L i n k : Then I found out now, I’ve got twelve

cases that were in this other group from 69 through 134

that should have been on the 13th because that was the

offense date rather than the arrest date. And Mr. Tucker

has them listed on his docket. He’s got them listed on

the arrest date.

M r . T. F. T u c k e r : Well, that’s the only date we had.

That’s the only way we could do it because at the time

we issued . . . if you’ll look at the papers, there was

nothing on there that we could tell or foresee that the

offense date would play such an important part in sched

uling these cases.

App. 5

Miss H arvey : And I might say, of course, Mr. Link

had a rather difficult time getting these cases together

and so that as soon as we could get his list for the sched

uling of the dates it was very difficult for us to notify

all of these people.

J udge A i k e n : I can see tha t. I th ink there are some

difficulties on both sides.

M iss H arvey: He had difficulties and through him

getting the dates late to us, then it threw us late trying to

get word to the people.

Mr. L in k : Yes, I had a whole lot of trouble.

J udge A i k e n : I realize that there are difficulties on

both sides and I want to be as fair as I can with both

sides. I want to be as lenient as we can, reasonably, with

these people that are on the bonds, Mrs. Hughes and

some of the others here. I want to give them every rea

sonable opportunity to get the defendants here that they

are tied up on.

J udge A i k e n : Jerry, have you any idea how long it

would take you to get the out-of-town clients here, like

those who live in Washington and New York, and one

of them in Iowa?

Mr. W il l ia m s : Yes, sir. Well, we could see how the

court is going to run say after the 28th, the 29th or some

where. I think that would give us plenty of time to get

them all here.

J udge A i k e n : It ought not to take that long to

H* H1

* * *

App. 6

Appendix No. 3

[tr . p . 10]

C ham bers

* * * would be a duplication of evidence if we don’t try

them on the 10th and the 13th and the 15 th. We’ll be try

ing them in groups.

J udge A ik e n : Well, I think we can try some of them

out there today and get rid of them.

M r . L in k : But you’ve got to go back and summons

everybody that you summoned this morning, or practically

everybody, in order to come back with the 10th again.

And the same would happen with the 13th too. And I

don’t know about these other cases, how many that are

missing on the 14th.

J udge A ik e n : How much time are we going to need

to try these out-of-town people ? Are they going to plead

guilty? They are not going to plead guilty? Well, then

it might take some time. What are these out here today

going to do? Are they going to plead guilty? They’re not

going to express any penitence or any regrets for violating

the Court’s orders ?

Miss H arvey : Well, the way you put it, Judge.

M r . W il l ia m s : They’re going to do all that. They’re

going to express all of that. But I mean we have to go

through with the . . . Of course, it’s a point that we . . .

M r . S. W . T u c k e r : W e w ant to try one case.

M r . W il l ia m s : . . . will make it the trial, won’t we?

J udge A ik e n : You want to try one case ?

App.7

* * *

[ t k . pp . 212-213]

F ERGUSO N---ARGU M E N T

* * * in any manner or apologized to this Court. And I’ll

say one further thing and I ’ll sit down. Courts since

there have been courts in this world prior to the birth of

Christ have always had powers to summarily punish for

the disobedience of his orders. As long as there has been

a history of law and order in this world, Courts have had

that power. It’s historic, and without it a Court could not

enforce its decrees. If people could with impunity . . . for

example, if you ordered me to do a certain thing and I

could flaunt that completely without any of your powers

to punish me for the wilful disobedience of some order,

you might as well not be sitting on the bench. And by

“you” I mean in the person of you any Judge in this land.

We must live under rules and regulations and without

them we live in a law of the jungle. And I see no apolo

getic countenance on any of these individuals or any

comment from anybody that “We’re sorry for what we

did,” or “we apologize if we made a mistake.” And for

that reason I certainly have no recommendations of len

iency involved in these individuals who caused open riots

in our community in 1963.

J udge A ik e n : All right. We’ve got to wind this matter

up. The Court is considerably disappointed about these

defendants. As Mr. Ferguson pointed out, not a single

defendant has expressed any regret for disobeying the

Court’s orders. Not a single lawyer representing these

defendants has expressed any regret about it that I re

call. They are not willing to say that they were mistaken

App. 8

and misguided in doing what they did, and maybe they

don’t think so. I don’t know. I am disappointed too in

the attitude of some of the leaders of this movement,

especially the ministers. Now I don’t think it ought to

be held against Reverend McGhee that he started to pray

out there. That’s all right. What I am disappointed in

about Reverend McGhee is that I know that he is an in

telligent man and he is a minister; and the Court thinks

that he ought to have been advising the people that he

was leading there that night to obey the Court’s order

rather than leading them in demonstrations But this

Court is not going to be very hard on Reverend McGhee.

The Court feels that it is its duty to uphold the dignity and

self-respect of this Court. And when this Court makes

an order, it’s got to be obeyed and anybody who violates

it has got to pay some penalty for it even though it may

be small.

Whereupon the Court found each of the following de

fendants guilty of violating the Court’s injunction as of

June the 10th, 1963 and fines and sentences to confine

ment were imposed as * * *

* * *