University of Tennessee v. Elliott Brief for Petitioners

Public Court Documents

January 30, 1986

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. University of Tennessee v. Elliott Brief for Petitioners, 1986. 3685bed9-c59a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5406e212-f756-4c25-8d40-c471b68ce586/university-of-tennessee-v-elliott-brief-for-petitioners. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Copied!

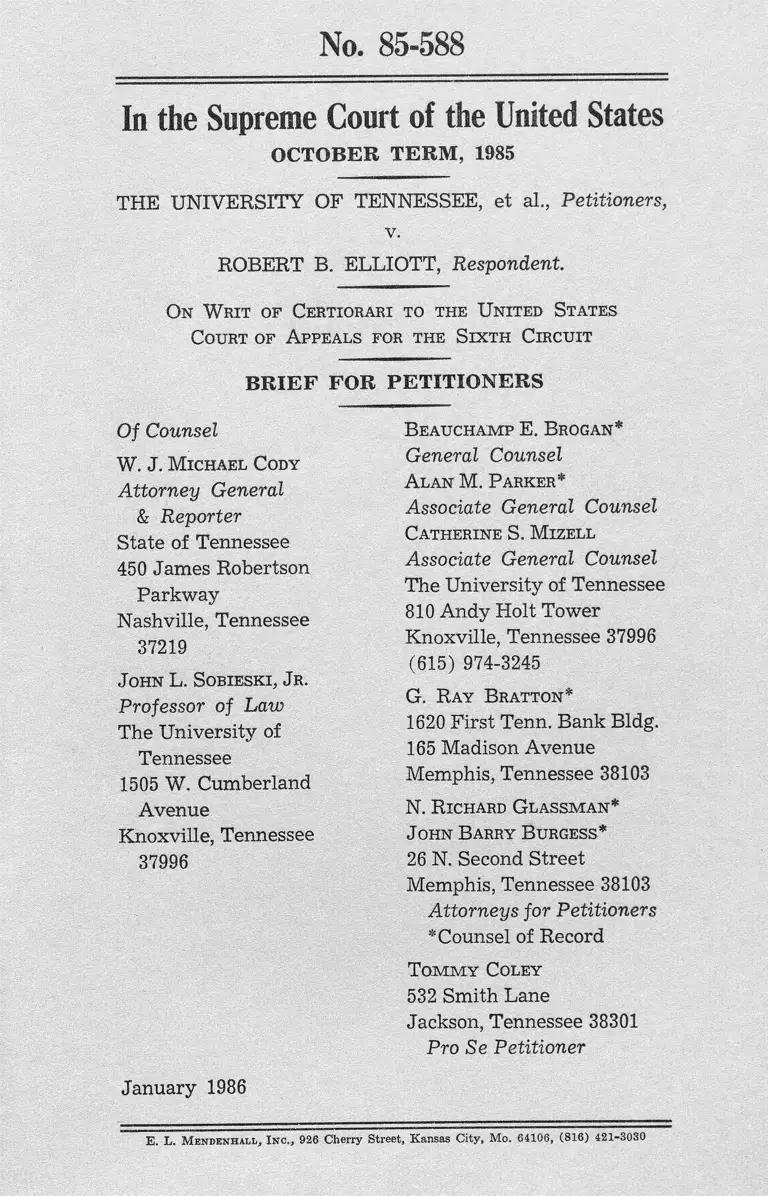

No. 85-588

In the Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM , 1985

THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE, et al., Petitioners,

v.

ROBERT B. ELLIOTT, Respondent.

O n W rit of Certiorari to the United States

Court of A ppeals for the S ixth Circuit

B R IE F FOR PETITIONERS

Of Counsel

W, J. M ichael Cody

Attorney General

& Reporter

State of Tennessee

450 James Robertson

Parkway

Nashville, Tennessee

37219

John L. Sobieski, Jr .

Professor of Law

The University of

Tennessee

1505 W. Cumberland

Avenue

Knoxville, Tennessee

37996

January 1986

B eauchamp E. Brogan*

General Counsel

A lan M. P arker*

Associate General Counsel

Catherine S. M izell

Associate General Counsel

The University of Tennessee

810 Andy Holt Tower

Knoxville, Tennessee 37996

(615) 974-3245

G. R ay B ratton*

1620 First Tenn. Bank Bldg.

165 Madison Avenue

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

N. R ichard G la ssm a n *

John B arry B urgess*

26 N. Second Street

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

Attorneys for Petitioners

* Counsel of Record

T o m m y Coley

532 Smith Lane

Jackson, Tennessee 38301

Pro Se Petitioner

E. L. M endenhall, I nc., 926 Cherry Street, Kansas City, Mo. 64106, (816) 421-8030

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether traditional principles of full faith and

credit apply in federal civil rights actions under the Re

construction statutes to issues fully and fairly litigated

before a state agency acting in a judicial capacity.

2. Whether traditional principles of full faith and

credit apply in Title VII actions to issues fully and fairly

litigated solely at the insistence of the aggrieved employee

before a state agency acting in a judicial capacity outside

the Title VII enforcement scheme.

n

TABLE OF CONTENTS

QUESTIONS PRESENTED .......................... ...... ....... . i

TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................. n

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .............................................. xv

OPINIONS BELOW .......................................... 1

JURISDICTION .................................................................... 2

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISION AND STATUTES

INVOLVED ........................................................ 2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE .......................... 2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ...................................... - 12

ARGUMENT

I. TRADITIONAL PRINCIPLES OF FULL

FAITH AND CREDIT APPLY IN FEDERAL

CIVIL RIGHTS ACTIONS UNDER THE RE

CONSTRUCTION STATUTES TO ISSUES

FULLY AND FAIRLY LITIGATED BEFORE

A STATE AGENCY ACTING IN A JUDI

CIAL CAPACITY .............................................. 16

A. This Court Has Consistently Held That

Civil Rights Actions Under The Recon

struction Statutes Are Not Categorically

Exempt From Traditional Principles Of

Full Faith And Credit.................................. 16

B. Traditional Principles Of Full Faith And

Credit Apply To The Final Judgment Of

A State Agency Acting In A Judicial

Capacity ......................................................... 22

1. This Court Has Never Recognized An

Artificial Distinction Between State

Agency Adjudications And State Court

in

Adjudications For Full Faith And

Credit Purposes ...................................... 22

2. Denial Of Full Faith And Credit To

The Final Agency Judgment In This

Case Would Seriously Undermine The

Integrity Of State Agency Adjudica

tions Conducted For The Purpose Of

Protecting Fourteenth Amendment

Due Process Interests ................ 27

II. TRADITIONAL PRINCIPLES OF FULL

FAITH AND CREDIT APPLY IN TITLE

VII ACTIONS TO ISSUES FULLY AND

FAIRLY LITIGATED SOLELY AT THE IN

SISTENCE OF THE AGGRIEVED EM

PLOYEE BEFORE A STATE AGENCY ACT

ING IN A JUDICIAL CAPACITY OUTSIDE

THE TITLE VII ENFORCEMENT SCHEME 31

A. Title VII Actions Are Not Categorically

Exempt From Traditional Principles Of

Full Faith And Credit _____ _________ _ 31

B. No Provision Of Title VII Required Re

spondent To Litigate The Issue Of Racial

Discrimination In The State Agency Pro

ceeding; Nor Does Any Provision Of Title

VII Specify The Effect Of The Final

Agency Judgment ................ ....................... 32

C. Full Faith And Credit Applies To Issues

Properly Before And Fully And Fairly

Adjudicated By A State Agency Acting In

A Judicial Capacity ........... ...... .......... ......... 35

D. The Issue Of Racial Discrimination Was

Fully And Fairly Litigated In The State

Proceeding .................... ......... - ................... 38

CONCLUSION ................................ -........ -.......................... 43

IV

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36 (1974) 30

Allen v. McCurry, 449 U.S. 90 (1980) ...................... passim

Baldwin v. Iowa State Traveling Men’s Ass’n, 283 U.S.

522 (1931) ....................................................................... 30

Board of Regents v. Roth, 408 U.S. 564 (1972) ........... 28

Bottini v. Sadore Management Corp., 764 F.2d 116

(2d Cir. 1985) ................................................................. 35

Bowen v. United States, 570 F.2d 1311 (7th Cir. 1978) 26

Buckhalter v. Pepsi-Cola General Bottlers, Inc., 768

F.2d 842 (7th Cir. 1985), petition for cert, filed ,.......

U.S.L.W......... (U.S. Dec. 23, 1985) (No. 85-6094) ....... 35

Chicago R.I. & P. Ry. v. Schendel, 270 U.S. 611 (1926)

........................................................................................... .13, 22

Delamater v. Schweiker, 721 F.2d 50 (2d Cir. 1983) 26

Elliott v. University of Tennessee, 766 F.2d 982 (6th

Cir. 1985) ....................................................................... 23,24

FTC v. Ruberoid Co., 343 U.S. 470 (1952) ...................... 28

Fourakre v. Perry, 667 S.W.2d 483 (Tenn. App. 1983) 20

Gear v. City of Des Moines, 514 F. Supp. 1218 (S.D.

Iowa 1981) ....................................................................... 23

Gulf Oil Corp. v. FPC, 563 F.2d 588 (3d Cir. 1977),

cert, denied, 434 U.S. 1062 (1978) .............................. 26

Heath v. John Morrell & Co., 768 F.2d 245 (8th Cir.

1985) ................................................................................... 35

International Wire v. Local 38, IBEW, 357 F.Supp. 1018

(N.D. Ohio 1972), affd, 475 F.2d 1078 (6th Cir.),

cert, denied, 414 U.S. 867 (1973) .... 26

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421 U.S.

454 (1975) 30

V

Jones v. Progress Lighting Corp., 595 F. Supp. 1031

(E.D. Pa. 1984) ................................... ............................ 35

Kremer v. Chemical Construction Corp., 456 U.S. 461

(1982) ........................................................................... passim

Magnolia Petroleum Co. v. Hunt, 320 U.S. 430 (1943)

.......................................................................................13, 22, 23

Marrese v. American Academy of Orthopaedic Sur

geons, .......U.S.......... , 105 S. Ct. 1327 (1985) ....15, 27, 36, 37

McCulloch Interstate Gas Corp. v. FPC, 536 F.2d 910

(10th Cir. 1976) .......................................... 26

McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792

(1973) ............................................................................... 41

Migra v. Warren City School District, 465 U.S. 75

(1984) ........... ...passim

Moore v. Bonner, 695 F.2d 799 (4th Cir. 1982) ............. 23

New York Gaslight Club, Inc. v. Carey, 447 U.S. 54

(1980) ............................................................................... 37

O’Connor v. Mazzullo, 536 F. Supp. 641 (S.D.N.Y.

1982) ............................................................................................. 23

O’Hara v. Board of Education, 590 F. Supp. 696 (D.N.J.

1984), aff’d mem., 760 F.2d 259 (3d Cir. 1985) ......... 35

Pacific Seafarers, Inc. v. Pacific Far East Line, Inc.,

404 F.2d 804 (D.C. Cir. 1968), cert, denied, 393 U.S.

1093 (1969) ......................... 26

Painters District Council No. 38 v. Edgewood Contract

ing Co., 416 F.2d 1081 (5th Cir. 1969) ................ 26

Parker v. National Corp. for Housing Partnerships, 619

F. Supp. 1061 (D.D.C. 1985) .. ....................................... 35

Patsy v. Board of Regents, 457 U.S. 496 (1982) .......... 21

Pettus v. American Airlines, Inc., 587 F.2d 627 (4th

Cir. 1978), cert, denied, 444 U.S. 883 (1979) ............... 26

Polsky v. Atkins, 197 Tenn. 201, 270 S.W.2d 497

(1954) 20

VI

Purcell Enterprises, Inc. v. State, 631 S.W.2d 401 (Tenn.

App. 1981) ......................................................................... 20

Reedy v. Florida, 605 F. Supp. 172 (N.D. Fla. 1985) 35

Riley v. New York Trust Co., 315 U.S. 343 (1942) .... 24

Snow v. Nevada Department of Prisons, 543 F. Supp.

752 (D. Nev. 1982) .................................................... .23,35

Steffen v. Housewright, 665 F.2d 245 (8th Cir. 1981) 23

Stone v. Powell, 428 U.S. 465 (1976) ................. ........ . 17

Texas Department of Community Affairs v. Burdine,

450 U.S. 248 (1981) ............. ............. ...... ............... ........ 41

Thomas v. Washington Gas Light Co., 448 U.S. 261

(1980) ............................... - ............. -............................13,22

United Farm Workers v. Arizona Agricultural Employ

ment Relations Board, 669 F.2d 1249 (9th Cir. 1982) 26

United States v. Karlen, 645 F.2d 635 (8th Cir. 1981) 26

United States v. Utah Construction & Mining Co., 384

U.S. 394 (1966) ............. ...... - ....... ......... -.... -.... -.... —.13, 25

Zanghi v. Incorporated Village of Old Brookville, 752

F.2d 42 (2d Cir. 1985) ........................ .................. ..... 23

Constitutional Provision

U.S. Const, art. IV, § 1 ........ .............................. ...... ....... 2, 12

Federal Statutes

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) (1982) ...... 2

28 U.S.C. § 1738 (1982) ...........................................................................................2,12,17

The Reconstruction Civil Rights Statutes, 42 U.S.C.

§§ 1981, 1983, 1985, 1986, 1988 (1982) ...................passim

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e et seq. (1982) .................. passim

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(b) (1982) ............................. 2,34

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 (c), (d) (1982) .................................... 2,33

VII

State Statutes

Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-5-102(3) (1985) ......................... .2,24

Tenn. Code Ann. §§ 4-5-301 through-323 (1985) .........2,4,

6, 29

Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-5-302 (1985) .................................. 6

Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-5-315 (1985) .................................. 10

Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-5-317 (1985) .................................. 10

Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-5-322 (1985) .................................. 11

Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-5-322(h) (1) (1985) .................7,15,36

Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-21-202 (1985)........................ .. ...... 33

Miscellaneous

1 K. Davis, Administrative Law Treatise (1983) ........... 29

Restatement (Second) of Judgments (1982) ............... 29

2 J. Cook & J. Sobieski, Civil Rights Actions (1985)

.... .................................................................................. ..... 30, 31

No. 85-588

In the Supreme Court of the United States

OCTOBER TERM, 1985

THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE, et al., Petitioners,

v.

ROBERT B. ELLIOTT, Respondent.

On W rit of Certiorari to the United States

Court of A ppeals for the S ixth Circuit

BRIEF FOR PETITIONERS

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Court of Appeals for the Sixth Cir

cuit is reported in 766 F.2d 982 (6th Cir. 1985). A copy

of the slip opinion and the judgment of the Court of Ap

peals appear in the Appendix to the Petition for Certiorari.

(P.A. 1-25; 183-184)1 The memorandum decision of the

United States District Court for the Western District of

Tennessee was not reported but appears in the Appendix

to the Petition for Certiorari. (P.A. 26-32) The judgment

of the District Court appears in the Joint Appendix. (J.A.

32) The final agency order in the contested case hearing

under the Tennessee Uniform Administrative Procedures

Act appears in the Appendix to the Petition for Certiorari.

(P.A. 33-35)

1. References to the Joint Appendix are cited as “ J.A.”

References to items reproduced in the Appendix to the Petition

for Certiorari are cited as “P.A.”

2

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals for the Sixth

Circuit was entered on July 9, 1985. The petition for a

writ of certiorari was filed on October 3, 1985, and granted

on December 2, 1985. This Court’s jurisdiction is invoked

under 28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) (1982).

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISION AND

STATUTES INVOLVED

The text of the following constitutional provision and

statutes relevant to the determination of this case are set

forth in appendices to this brief: U.S. Const, art. IV, § 1;

28 U.S.C. § 1738 (1982); 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(b), (c), (d)

(1982); Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-5-102(3) (1985); Tenn. Code

Ann. §§ 4-5-301 through -323 (1985).

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This is an action under the Reconstruction civil rights

statutes, 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1983, 1985, 1986, and 1988

(1982), and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42

U.S.C. § 2000e et seq. (1982), in which respondent, Robert

B. Elliott, alleges that petitioners2 have engaged in racial

discrimination against him. Petitioners seek application

of issue preclusion in this action on the ground that a

2. Petitioners are all defendants below—The University of

Tennessee, The University of Tennessee Institute of Agriculture,

The University of Tennessee Agricultural Extension Service,

University officials (M. Lloyd Downen, Willis W. Armistead,

Edward J. Boling, Haywood W. Luck, and Curtis Shearon), mem

bers of the Madison County Agricultural Extension Service Com

mittee (Billy Donnell, Arthur Johnson, Jr., Mrs. Neil Smith,

Jimmy Hopper, and Mrs. Robert Cathey), Murray Truck Lines,

Inc., Tom Korwin, and Tommy Coley.

3

prior state adjudication, voluntarily invoked by respondent

under the Tennessee Uniform Administrative Procedures

Act for the purpose of defending his liberty and property

interests under the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment, is entitled to full faith and credit in federal

court.

A. Respondent’s Proposed Termination.

Respondent is employed as an Associate Extension

Agent with The University of Tennessee Agricultural Ex

tension Service. During 1981 respondent’s superiors ob

served what in their judgment were instances of inade

quate work performance and improper job behavior. Re

spondent’s immediate supervisor and the Dean of the

Agricultural Extension Service instituted the University’s

multi-step disciplinary process in an effort to improve

respondent’s performance and behavior. These efforts

were unsuccessful, however, and instances of inadequate

performance and improper behavior continued. (J.A. 21)

In December 1981, the University proposed to terminate

respondent’s employment.3 (J.A. 21-23)

In a letter dated December 18, 1981, the University

notified respondent of the disciplinary charges and his

right to a due process hearing prior to the proposed termi

nation. (J.A. 21-23) On December 22, 1981, in a written

response made by his attorney, respondent demanded a

3. The disciplinary charges included allegations of failure

to carry out specific work assignments in a timely and proper

manner; insubordination; engaging during University working

hours in a personal custom cabinet business; playing golf without

permission during working hours; making anonymous harassing

phone calls to a private citizen in violation of University work

rules; public verbal abuse of private citizens; unexcused ab

sences; and unauthorized use of official University telephone for

personal long distance calls. (P.A. 39-43)

4

formal, trial-type hearing under the contested case pro

visions of the Tennessee Uniform Administrative Proce

dures Act, Tenn, Code Ann. §§ 4-5-301 through -323 (1985),

to contest the disciplinary charges. Respondent also stated

that he intended to prove in the contested case hearing

that the University was guilty of racial harassment of

him. (Dist. Ct. Nr. 8, Exhibit M to Affidavit of M. Lloyd

Downen, filed Feb. 18, 1982)

B. Respondent’s District Court Complaint.

On January 5, 1982, before the due process hearing

was convened,4 and before the EEOC had taken any ac

tion on the discrimination charge he had filed in late De

cember 1981, respondent filed this federal court action

under the Reconstruction civil rights statutes and Title VII.

(J.A. 2-18) Respondent’s complaint sought to enjoin the

University from taking any employment action against

him, one million dollars in damages, and certification of a

class action.5 (J.A. 17-18)

Respondent’s complaint included allegations of racial

discrimination against him based on the same incidents

out of which the University’s disciplinary charges arose.

Respondent alleged that these incidents, and the disciplin

ary charges themselves, were acts of racial discrimination

and harassment against him by the University, University

officials, and the other petitioners.

On January 19, 1982, the district court entered ex parte

a temporary restraining order prohibiting the University

from taking any disciplinary action against respondent.

(Dist. Ct. Nr. 4) The University responded with a motion

4. The hearing was not convened because of the holiday

season.

5. The district court did not certify a class action.

5

to dissolve the temporary restraining order, to dismiss the

complaint, and for summary judgment, asserting that re

spondent did not meet the prerequisites for preliminary

injunctive relief nor the jurisdictional prerequisites for a

Title VII action. (J.A. 19-20) The district court, without

ruling on the University’s motion to dismiss and for sum

mary judgment, dissolved the temporary restraining order,

ruling that respondent was not entitled to preliminary in

junctive relief. (Dist. Ct. Nr. 12, Feb. 23, 1982)

C. Respondent’s Departure From The Available Fed

eral Forums To Invoke The State Due Process

Hearing.

Upon dissolution of the temporary restraining order,

respondent completely abandoned his Title VII and Re

construction civil rights claims. Respondent did not seek

a Title VII right-to-sue letter at that time or otherwise

press his claim within the Title VII enforcement scheme.

Nor did he in any way prosecute in federal court his claims

under the Reconstruction civil rights statutes. Respon

dent instead departed entirely from the available federal

forums to contest the disciplinary charges in a due process

hearing under the Tennessee Uniform Administrative Pro

cedures Act.

The due process hearing convened on April 26, 1982,6

well past the time when respondent could have requested

a Title VII right-to-sue letter. With various recesses, the

hearing continued intermittently until October 1982 for

a total of twenty-eight days of testimony and argument.

(P.A. 36-37)

6. The hearing was a public hearing held in Jackson,

Tennessee (over 300 miles from the University headquarters in

Knoxville) for the convenience of respondent and his multitude

of witnesses.

6

In compliance with Tenn. Code Ann. §§ 4-5-301 through

-323 (1985), the hearing was conducted with procedural

rights which in all respects were identical to those avail

able to civil trial litigants under the Tennessee and Fed

eral Rules of Civil Procedure. These trial-like procedural

rights included discovery in accordance with the Ten

nessee Rules of Civil Procedure; compulsory process to

discover and produce documents and witnesses for trial;

examination and cross-examination of witnesses; applica

tion of rules of evidence; and filing of pleadings, motions,

objections, briefs, proposed findings of fact and conclusions

of law, and proposed orders. In addition, under the pro

visions of Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-5-302 (1985), respondent

could have petitioned for disqualification of the Admin

istrative Law Judge for “ bias, prejudice, interest . . . or

for any cause for which a judge may be disqualified.”

Respondent did not petition for disqualification of the

Administrative Law Judge. Nor did he ever challenge the

procedural adequacy or fairness of the state proceedings.

To the contrary, he fully availed himself of the trial-like

procedural rights provided by the Administrative Proce

dures Act, as is demonstrated by the voluminous hearing

record. The transcript alone consists of 55 volumes, in

cluding 159 exhibits7 and 5,000 pages of testimony (P.A.

27) from 104 witnesses, 93 of whom were produced by

respondent. Over 100 witness and document subpoenas

were issued at respondent’s request. Respondent’s coun

sel filed briefs, supplemental briefs, and lengthy proposed

findings of fact and conclusions of law.

7. The vast majority of exhibits were entered by respon

dent. Some contained over 100 parts, including photographic

prints, slides, and even videotapes displayed in the open hearing.

7

D. Litigation Of The Issue Of Racial Discrimination

As An Affirmative Defense To The Disciplinary

Charges.

As the charging party in the due process hearing, the

University carried the same burden of persuasion as a

plaintiff in a civil trial. The University was required to

prove the disciplinary charges by a preponderance of the

evidence. Respondent had the right under Tenn. Code

Ann. § 4-5-322 (h) (1) (1985) to defend the charges on

the basis that the agency was acting “ [i]n violation of

constitutional or statutory provisions.” Availing himself

of this right, respondent defended on the ground that the

charges were racially motivated.

On the first day of the due process hearing, respondent

sought to file countercharges of racial discrimination to be

tried in the due process hearing. The Administrative Law

Judge refused to allow the filing of countercharges, ruling

that he was not empowered to dispose of respondent’s Re

construction civil rights or Title VII claims. The Ad

ministrative Law Judge further ruled, however, that he was

empowered to determine the issue of discrimination as an

affirmative defense to the disciplinary charges. (P.A.

44-45, 171)

Respondent fully pursued this affirmative defense

and introduced voluminous evidence as to the allegations

of individual racial discrimination included in his federal

court complaint. Through direct or cross-examination of

all 104 witnesses, respondent’s counsel sought to establish

the discriminatory intent of all parties named as defen

dants in the federal court complaint with respect to the

allegations of individual discrimination alleged in the com

plaint.

8

E. Findings Of The Administrative Law Judge.

In a lengthy order including extensive findings of

fact and conclusions of law, the Administrative Law Judge

found that the University had sustained its burden of

persuasion on four charges of improper job behavior.8

With respect to the other disciplinary charges, the Ad

ministrative Law Judge found that the University either

failed to sustain its burden of persuasion or had not pro

vided proper supervision of respondent’s work performance.

(P.A. 166-170)

The Administrative Law Judge made extensive find

ings on respondent’s affirmative defense that the dis

ciplinary charges were racially motivated. Addressing first

the appropriate burden of persuasion with respect to the

affirmative defense, the Administrative Law Judge ruled

that

[sjince this is not a civil rights case under Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 as amended, 42 U.S.C.

Sec. 2Q00e, et seq., nor under 42 U.S.C. Sec. 1983, in

order to successfully defend [sic] charges of race

discrimination, employee must prove by a preponder

ance of the evidence that the disciplinary actions taken

8. Specifically, the Administrative Law Judge found (1)

that respondent was guilty of playing golf without permission

during working hours and in violation of University policy; (2)

that respondent falsely made written, public accusations that a

private livestock judge refused to make judging decisions in

favor of black 4-H youths, the contrary facts being publicly

available to respondent; and that respondent’s public, profane

epithets in front of the livestock judge and false accusation “ were

unjustified and not protected freedom of speech under the con

stitution, and evidenced traits undesirable in an AES employee” ;

(3) that respondent’s conduct in front of the private livestock

judge constituted disorderly conduct and abusive language in

violation of University rules; and (4) that respondent made nu

merous personal long distance calls from a University business

phone in violation of University rules. (P.A. 177-178)

9

against him were because of his race, and that his

supervisors only used the charges of improper job

behavior and inadequate job performance as a pretext

to propose his termination because he is black. Thus,

in his defense, Elliott had the same burden of proving

pretext as contained in McDonnell Douglas Corp. v.

Greene, 411 U.S. 792 (1973) and Texas Department

of Community Affairs v. Burdine, 101 S.Ct. 1089

(1981).

(P.A. 171)

After a thorough review of the evidence, the Ad

ministrative Law Judge made the following ultimate find

ing on respondent’s affirmative defense to the disciplinary

charges:

An overall and thorough review of the entire

evidence of record leads me to believe that employer’s

action in bringing the charges against employee, re

sulting in these proceedings were based on what it,

through its administrative officers and supervisors per

ceived as improper and/or inadequate behavior and

inadequate job performance rather than racial dis

crimination. I therefore conclude that employee has

failed in his burden of proof to the claim of racial

discrimination as a defense to the charges against

him.

(P.A. 177)

Despite finding that the University’s proposal to termi

nate respondent was for valid disciplinary reasons and was

not racially motivated, the Administrative Law Judge or

dered that respondent be given another chance to improve

his job behavior. The Administrative Law Judge ordered,

therefore, that respondent not be terminated but instead

10

transferred to the same position in another county under

new supervisors. (P.A. 180-181)

F. Appeal Of The Findings To The Agency Head.

Pursuant to Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-5-317 (1985), both

respondent and the University petitioned the Administra

tive Law Judge to reconsider his initial order. The Uni

versity challenged the decision not to terminate respon

dent. Respondent, on the other hand, challenged the

decision to transfer him and urged once again that the

disciplinary charges were racially motivated. The Ad

ministrative Law Judge denied both petitions, and respon

dent then appealed to the Agency Head under the pro

visions of Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-5-315 (1985). The Agency

Head affirmed the findings of the Administrative Law

Judge and made the following independent finding on

the issue of racial discrimination:

I am also convinced from my review of the record

that the action of the Extension Service in proposing

the termination of employee’s services was not moti

vated by employee’s race but by a desire to terminate

employee for what the Extension Service sincerely

believed to be inadequate job performance and inade

quate job behaviour.

(P.A. 34) The Agency Head also affirmed the Adminis

trative Law Judge’s conclusion that respondent be trans

ferred to another county on the ground that the proof

“was not sufficient under the circumstances to warrant

dismissal.” (P.A. 34) Respondent’s employment was never

interrupted during the state proceedings and continues

today.

11

G. Respondent’s Return To Federal Court After The

Final Agency Judgment.

Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-5-322 (1985) provides that the

only available method of judicial review of a final agency

order is by the filing of a petition for review in state

chancery court within sixty days of the order. Respon

dent did not file a timely petition for judicial review.

Instead, two months after his transfer had taken place,

and eighty-four days after the final agency judgment had

been entered, respondent returned to federal district court

in late October 1983. (P.A. 29) Eighteen months had

passed from the time respondent had departed from the

available federal forums to press the issue of racial dis

crimination in the due process hearing.

Upon returning to the district court, respondent did

not seek de novo review of the issue of racial discrimina

tion. Instead, consistent with his earlier departure from

the federal forums, respondent filed a motion simply seek

ing review of the merits of the final agency judgment

on the basis of the voluminous record of the state pro

ceedings. (J.A. 24-30) Respondent never filed a Title

VII right-to-sue letter in the district court or otherwise

requested a de novo review of his Title VII or Recon

struction civil rights claims in the district court.

H. The Decisions Below.

On May 12, 1984, the district court granted summary

judgment in favor of all defendants, holding that it lacked

jurisdiction to review the merits of the final agency order

and that res judicata precluded relitigation of the issue

of racial discrimination fully and fairly adjudicated in

the due process hearing. (P.A. 26-32)

12

Respondent appealed to the Court of Appeals for

the Sixth Circuit and for the first time contended that

he was entitled to de novo review of the issue of racial

discrimination under Title VII and the Reconstruction

statutes. The Sixth Circuit reversed the district court

and held that, in the absence of state court review, no

issue adjudicated by a state administrative agency is ever

entitled to preclusive effect in a subsequent employment

discrimination action under Title VII or the Reconstruction

statutes. (P.A. 1-25)

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Although no provision of the Reconstruction civil

rights statutes, Title VII, or any other federal law

required him to do so, respondent purposefully de

parted from the available federal forums and fully litigated

the issue of racial discrimination in a state agency adju

dication conducted for the purpose of protecting his Four

teenth Amendment liberty and property interests. The

final agency judgment is entitled to preclusive effect in

Tennessee state courts and thus is also entitled, under

the full faith and credit clause, U.S. Const, art. IV, § 1,

and statute, 28 U.S.C. § 1738 (1982), to preclusive effect

in respondent’s subsequent federal court action under the

Reconstruction statutes and Title VII.

This Court’s decisions in Allen v. McCurry, 449 U.S.

90 (1980), and Migra v. Warren City School District, 465

U.S. 75 (1984), demonstrate a firm commitment to tradi

tional principles of full faith and credit in civil rights

actions and unequivocally establish that the Reconstruc

tion statutes do not repeal the mandate of full faith and

credit. Emphatically rejecting the notion that state ad

judication of a federal right cannot be trusted, the

13

Allen and Migra decisions clearly articulate the full faith

and credit analysis required of federal courts: Whether

the prior state adjudication is entitled to preclusive effect

in the courts of the state in which it was rendered and,

if so, whether the party against whom preclusion is as

serted had a full and fair opportunity to litigate in the

state forum. The Sixth Circuit failed to apply the full

faith and credit analysis prescribed by Allen and Migra

and denied issue preclusion in this case even though the

prior adjudication unquestionably is entitled to preclusive

effect in Tennessee courts and even though the federal

district court itself found that respondent had received

full procedural due process in the state proceeding.

Decisions of this Court not only establish that there

is no exception to traditional principles of full faith and

credit for Reconstruction civil rights actions, but also

that there is no exception to the full faith and credit due

an adjudication of issues by a state agency acting in a

judicial capacity. See Thomas v. Washington Gas Light

Co., 448 U.S. 261 (1980); Magnolia Petroleum Co. v.

Hunt, 320 U.S. 430 (1943); Chicago R.I. & P. Ry. v.

Schendel, 270 U.S. 611 (1926); see also Kremer v. Chemical

Construction Corp., 456 U.S. 461, 485 n.26 (1982); United

States v. Utah Construction & Mining Co., 384 U.S. 394, 422

(1966) (traditional rules of issue preclusion apply to de

cisions by agencies acting in a judicial capacity). Indeed,

the very purpose of full faith and credit—to place national

sanction behind state laws of preclusion—can be accom

plished only if the effect of a state judgment, whether

rendered by a court or by an agency acting in a judicial

capacity, is determined according to the rules of preclu

sion of the state in which it was rendered.

14

Distrust of a state agency adjudication is completely

unwarranted when the adjudication is provided by state

law for the express purpose of protecting an individual’s

constitutional and statutory rights against arbitrary state

action. When the state proceeding, voluntarily invoked,

provides all the procedural safeguards of a federal court

proceeding, the policy considerations supporting rules of

preclusion as well as concerns of comity and federalism

demand that federal courts apply full faith and credit

to the final agency judgment.

This Court’s commitment to traditional principles of

full faith and credit extends to Title VII actions as well

as actions under the Reconstruction statutes. In Kremer

v. Chemical Construction Corp., 456 U.S. 461 (1982), this

Court squarely held that Title VII does not expressly

repeal the mandate of full faith and credit. This Court

also held in Kremer that Title VII does not impliedly

repeal the full faith and credit due a state court judgment

in a subsequent Title VII action.

Full faith and credit is equally mandated with re

spect to the Title VII action in this case. No provision of

Title VII can be construed as an express or implied repeal

of the full faith and credit due the final agency judgment

in this case. Nothing in Title VII required respondent

to invoke the state proceedings or to litigate the issue

of racial discrimination there. The only state proceedings

which must be invoked under Title VII are those estab

lished by state law to remedy employment discrimination.

Respondent, however, invoked a state statutory proceeding

provided for the protection of his liberty and property in

terests under the Fourteenth Amendment. No provision of

Title VII repeals the full faith and credit owing a state

15

agency adjudication voluntarily invoked by a state em

ployee outside the Title VII enforcement scheme.

There is no question that the issue of racial discrim

ination was properly before and wholly within the com

petence of the state tribunal voluntarily invoked by re

spondent. Under state law, respondent was entitled to

show that the University’s proposed termination of his

employment would be “ [i]n violation of constitutional or

statutory provisions.” Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-5-322(h) (1)

(1985). Respondent in fact defended on the ground that

the University’s actions were racially motivated, and pur

suant to the requirements of state law, voluminous evi

dence of alleged racial discrimination was admitted in

support of respondent’s affirmative defense to the disci

plinary charges. The fact that the state tribunal was not

empowered to determine respondent’s Title VII claim in

no way detracts from the full faith and credit due the

findings made within the conceded competence of the

tribunal to adjudicate respondent’s affirmative defense.

As this Court recently reaffirmed in Marrese v.

American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, ....... U.S.

......., 105 S. Ct. 1327 (1985), absent an exception to the

statutory command of full faith and credit, state law de

termines the issue preclusion effect of a state judgment

even with respect to claims within the exclusive jurisdic

tion of the federal courts.

There can be no doubt in this case that respondent

had every opportunity to and did litigate the issue of

racial discrimination fully and fairly in the state proceed

ings. The state proceedings were conducted in virtually

the same manner as a trial in state or federal court. Re

spondent was represented by counsel at every stage of

the proceedings and exercised the full array of procedural

16

rights available to him under state law. Indeed, respon

dent has never challenged in any state or federal proceed

ing below the adequacy or fairness of the procedures under

which his due process hearing was conducted. Denial of

full faith and credit to the state proceedings in this case

would not only undermine the integrity of those proceed

ings but also needlessly burden the federal court with

duplicative litigation. Respondent is fairly bound by his

chosen forum’s state law that one full and fair opportunity

to litigate an issue is enough.

ARGUMENT

I. TRADITIONAL PRINCIPLES OF FULL FAITH

AND CREDIT APPLY IN FEDERAL CIVIL

RIGHTS ACTIONS UNDER THE RECONSTRUC

TION STATUTES TO ISSUES FULLY AND

FAIRLY LITIGATED BEFORE A STATE

AGENCY ACTING IN A JUDICIAL CAPACITY.

A. This Court Has Consistently Held That Civil

Rights Actions Under The Reconstruction

Statutes Are Not Categorically Exempt From

Traditional Principles Of Full Faith And

Credit.

In Allen v. McCurry, 449 U.S. 90 (1980), this Court

endorsed the virtually unanimous view of the courts of

appeals that traditional principles of full faith and credit

are applicable in civil rights actions under the Reconstruc

tion statutes. If any case presented an especially appeal

ing situation for creating an exception to full faith and

credit, it was Allen. McCurry, the federal plaintiff in an

action under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 (1982), did not select the state

17

forum; he was, rather, a defendant in a state criminal pro

ceeding. The state’s interest in obtaining a conviction was

acute—McCurry was not only dealing in heroin, he shot

and seriously wounded two undercover police officers who

had gone to McCurry’s home to attempt a purchase. More

over, as a result of this Court’s decision in Stone v. Powell,

428 U.S. 465 (1976), McCurry’s § 1983 action was his only

avenue of access to a federal trial forum for litigation of

his federal constitutional claim.

Nonetheless, in Allen, this Court squarely held that

nothing in the language or legislative history of § 1983

suggests any congressional intent to contravene tradi

tional principles of issue preclusion or to repeal the

express statutory requirements of the full faith and

credit statute, 28 U.S.C. § 1738 (1982). In so holding, this

Court categorically rejected the notion that every person is

entitled to one unencumbered opportunity to litigate a

federal right in a federal district court:

[Njothing in the language or legislative history of

§ 1983 proves any congressional intent to deny binding

effect to a state-court judgment or decision when the

state court, acting within its proper jurisdiction, has

given the parties a full and fair opportunity to litigate

federal claims, and thereby has shown itself willing

and able to protect federal rights. . . . There is, in

short, no reason to believe that Congress intended to

provide a person claiming a federal right an unre

stricted opportunity to relitigate an issue already de

cided in state court simply because the issue arose in

a state proceeding in which he would rather not have

been engaged at all.

18

The only other conceivable basis for finding a uni

versal right to litigate a federal claim in a federal

district court is hardly a legal basis at all, but rather

a general distrust of the capacity of the state courts

to render correct decisions on constitutional issues.

It is ironic that Stone v. Powell provided the occasion

for the expression of such an attitude in the present

litigation, in view of this Court’s emphatic reaffirma

tion in that case of the constitutional obligation of

the state courts to uphold federal law, and its expres

sion of confidence in their ability to do so.

449 U.S. at 103-05.

The commitment to traditional principles of full faith

and credit in civil rights actions which this Court first

expressed in Allen was reaffirmed in Migra v. Warren

City School District, 465 U.S. 75 (1984). In Migra, this

Court unanimously agreed that a state court judgment is

entitled at least to as much claim preclusion effect in a

subsequent federal civil rights action under § 1983

as it would have in the courts of the state in which it

was rendered. Justice Blackmun, who dissented in Allen,

delivered the opinion of the Court. He readily acknowl

edged that the heart of the opinion in Allen—namely, that

state courts are as obligated and able to uphold federal

rights as federal courts—applies with just as much force

to claim preclusion as issue preclusion:

It is difficult to see how the policy concerns un

derlying § 1983 would justify a distinction between

the issue preclusive and claim preclusive effects of

state-court judgments. The argument that state-

court judgments should have less preclusive effect in

§ 1983 suits than in other federal suits is based on

Congress’ expressed concern over the adequacy of

19

state courts as protectors of federal rights. . . . Allen

recognized that the enactment of § 1983 was moti

vated partially out of such concern, . . . but Allen

nevertheless held that § 1983 did not open the way

to relitigation of an issue that had been determined

in a state criminal proceeding. Any distrust of state

courts that would justify a limitation on the preclusive

effect of state judgments in § 1983 suits would pre

sumably apply equally to issues that actually were

decided in a state court as well as to those that could

have been. If § 1983 created an exception to the gen

eral preclusive effect accorded to state-court judg

ments, such an exception would seem to require sim

ilar treatment of both issue preclusion and claim pre

clusion. Having rejected in Allen the view that state-

court judgments have no issue preclusive effect in

§ 1983 suits, we must reject the view that § 1983 pre

vents the judgment in petitioner’s state-court pro

ceeding from creating a claim preclusion bar in this

case.

465 U.S. at 83-84.

Thus, Allen and Migra clearly delineate the relevant

analysis with regard to the preclusive effect of a state

adjudication in a subsequent federal civil rights action

under the Reconstruction statutes. The relevant analysis

is unmistakably one of full faith and credit. As this Court

emphasized in Allen, a departure from traditional prin

ciples of full faith and credit can be justified only if plainly

intended by Congress. In Allen and Migra, however, this

Court found nothing in the language or legislative history

of § 1983 to suggest any congressional intent to contravene

traditional principles of preclusion or to repeal the express

statutory requirements of the full faith and credit statute.

20

A prior state adjudication is entitled to preclusive

effect in a subsequent federal civil rights action, there

fore, as long as the adjudication would preclude relitiga

tion of the claim or issue in the courts of the state in

which it was rendered. To this extent, the preclusive ef

fect of a prior state adjudication is defined as a matter

of state law. Federal law acts as a restraint only to the

extent of ensuring that the state proceedings afford the

party against whom preclusion is asserted a full and fair

opportunity to litigate. See Allen, 449 U.S. 90, 95 (1980).

Although ignored by the Sixth Circuit, the full faith

and credit analysis prescribed by this Court in Allen and

Migra requires that respondent be precluded from reliti

gating the issue of racial discrimination in his federal

court action under the Reconstruction civil rights statutes.

First, Tennessee law provides that an adjudication by a

state agency acting in a judicial capacity is entitled to

preclusive effect in Tennessee courts. See Polsky v. A t

kins, 197 Tenn. 201, 270 S.W.2d 497 (1954); Fourakre

v. Perry, 667 S.W.2d 483 (Tenn. App. 1983); Purcell En

terprises, Inc. v. State, 631 S.W.2d 401 (Tenn. App. 1981).

Second, there can be no doubt that respondent was afforded

a full and fair opportunity to litigate the issue of racial

discrimination. Respondent’s due process hearing was con

ducted with complete trial rights including discovery, wit

ness and document subpoenas, representation by counsel,

examination and cross-examination of witnesses, and filing

of pleadings, motions, objections, briefs, proposed findings

of fact and conclusions of law, and proposed orders. The

transcript portion of the hearing record alone is volumi

nous—55 volumes with over 5,000 pages of testimony from

104 witnesses, not to mention 159 exhibits. Respondent

called ninety-three witnesses. The issue of discrimination

hardly could have been litigated more fully in either state

21

or federal court. In fact, the district court made the follow

ing specific finding concerning respondent’s full and fair

opportunity to litigate in the due process hearing:

Plaintiff makes no claim of denial of procedural

due process. Nor can he in light of the long exhaus

tive evidentiary hearing in which plaintiff presented

more than ninety witnesses, and cross-examined some

of the agency’s witnesses for more than thirty hours

each. Plaintiff clearly has received full protection

in this due process hearing, as required in Board of

Regents v. Roth, 408 U.S. 564 (1972), and Perry v.

Sindermann, 408 U.S. 593 (1972).

(P.A. 31)

Indeed, this case unquestionably presents the most

appealing circumstance of all for applying traditional prin

ciples of full faith and credit in a civil rights action un

der the Reconstruction statutes. As a result of this Court’s

opinion in Patsy v. Board of Regents, 457 U.S. 496 (1982)

(exhaustion of state administrative remedies not required

in actions under § 1983), the decision to litigate the

charge of racial discrimination in the state proceed

ing rested solely with respondent. Although respon

dent could have avoided any state action on his Reconstruc

tion civil rights claim simply by litigating it in fed

eral court in the first place, he deliberately and vol

untarily invoked the state forum and vigorously liti

gated the issue of racial discrimination there as an affirma

tive defense to his proposed termination. In a searching

review of the evidence revealed in lengthy findings of

fact, the Administrative Law Judge found, however, that

respondent’s proposed termination was for valid discipli

nary reasons and was not racially motivated. This finding

was affirmed on appeal to the Agency Head. Judicial

22

review of the adverse finding was available, but respon

dent did not avail himself of the opportunity.

The findings of the state agency adjudication in this

case are entitled to preclusive effect in Tennessee courts

under Tennessee rules of preclusion. Respondent should

not be permitted now to flout state law and litigate the

issues yet again in a federal forum. To do so would

contravene all of the policy considerations justifying tradi

tional principles of preclusion and their adoption as na

tional policy through principles of full faith and credit.

B. Traditional Principles Of Full Faith And Credit

Apply To The Final Judgment Of A State

Agency Acting In A Judicial Capacity.

1. This Court Has Never Recognized An Arti

ficial Distinction Between State Agency

Adjudications And State Court Adjudica

tions For Full Faith And Credit Purposes.

This Court has never deviated from the principle that

state agency adjudications are entitled to the same issue

preclusion effect in other courts as they enjoy in the courts

of the rendering jurisdiction. Thomas v. Washington Gas

Light Co., 448 U.S. 261 (1980); Magnolia Petroleum Co. v.

Hunt, 320 U.S. 430 (1943); Chicago R.I. & P. Ry. v. Schen-

del, 270 U.S. 611 (1926). Justice Stevens’ statement on be

half of the plurality in Thomas could hardly have been more

explicit: “To be sure, . . . the factfindings of state admin

istrative tribunals are entitled to the same res judicata

effect in the second State as findings by a court.” 448

U.S. at 281. In the concurring and dissenting opinions

in Thomas, not a single member of this Court expressed

any disagreement with this statement of well-established

law. The Sixth Circuit’s ruling that full faith and credit

23

“does not require federal courts to defer to the unreviewed

findings of state administrative agencies,” Elliott v. Univer

sity of Tennessee, 766 F.2d 982, 990 (6th Cir. 1985), is

simply a refusal to recognize what this Court has already

recognized for at least six decades.9

Both the full faith and credit clause of the Constitu

tion, article IV, § 1, and the federal full faith and credit

statute, 28 U.S.C. § 1738 (1982), require that state “ [a]cts,

records and judicial proceedings” be given the same full

faith and credit as they enjoy in the courts of the render

ing state. As this Court stressed in Magnolia Petroleum

Co. v. Hunt, 320 U.S. 430 (1943),

[wjhether the proceeding before . . . [a state agency

acting in a judicial capacity is] regarded as a “judi

cial proceeding” , or its award is a “record” within

the meaning of the full faith and credit clause and

the Act of Congress, the result is the same. For ju

dicial proceedings and records of the state are both

required to have “such faith and credit given to them

in every court within the United States as they have

by law or usage in the courts of the State from which

they are taken.”

Id. at 443.

Under this nation’s federal scheme of government,

a state is free to exercise its judicial power through its

courts or, if it sees fit, through its executive and adminis

9. The decision of the Sixth Circuit refusing to give full

faith and credit to the state agency adjudication is inconsistent

with the weight of ■post-Allen lower court authority. See Zanghi

v. Incorporated Village of Old Brookville, 752 F.2d 42 (2d Cir.

1985); Steffen v. Housewright, 665 F,2d 245 (8th Cir. 1981); Snow

v. Nevada Dep’t of Prisons, 543 F. Supp. 752 (D. Nev. 1982);

O’Connor v. Mazzullo, 536 F. Supp. 641 (S.D.N.Y. 1982); Gear

v. City of Des Moines, 514 F. Supp. 1218 (S.D. Iowa 1981). But

see Moore v. Bonner, 695 F.2d 799 (4th Cir. 1982).

24

trative agencies. The judgments of such agencies, acting

judicially, are entitled to the same preclusive effect as

they enjoy in the state’s courts because the proceedings

are in fact “judicial proceedings” of the state within the

meaning of the full faith and credit clause and statute.

The very purpose of the full faith and credit clause and

statute is to put national sanction behind state policies

with respect to the effect of a judgment. See Riley v.

New York Trust Co., 315 U.S. 343, 349 (1942). That pur

pose can be fully realized only if the force and effect

of a judgment, whether rendered by a court or by a state

agency acting in a judicial capacity, is determined accord

ing to the law of the state of rendition. The decision

of the Sixth Circuit denies full faith and credit to the

very decisions of Tennessee courts holding that state

agency adjudications are entitled to preclusive effect in

Tennessee courts.

The State of Tennessee has empowered its agencies

to act in a judicial capacity to adjudicate contested cases

in which a person’s legal rights are required by constitu

tional or statutory provision to be determined prior to

proposed agency action. See Tenn. Code Ann. §

4-5-102(3) (1985). The Sixth Circuit concluded, however,

that “state determination of issues relevant to constitu

tional adjudication is not an adequate substitute for full

access to federal court.” Elliott, 766 F,2d at 992. There

is no support for this conclusion in decisions of this

Court. Allen and Migra unequivocally laid to rest any

notion that every person is entitled to one unencumbered

opportunity to litigate a federal right in federal court

“regardless of the legal posture in which the federal claim

arises.” Allen, 449 U.S. at 103.

Indeed, Allen and Migra are vivid illustrations of this

Court’s confidence in the ability of the states to vindicate

25

federal rights. When, as here, an agency adjudication

is provided by state law for the express purpose of protect

ing an individual's constitutional and statutory rights prior

to agency action, there is absolutely no reason to distrust

the adjudication. Moreover, according full faith and credit

to the state agency adjudication in this case in no way

undermines full access to federal court. The decision

to litigate the issue of racial discrimination in the state

proceeding rested solely with respondent. If respondent

wanted full access to federal court, it was his for the

taking.

This Court has recognized previously that principles

of issue preclusion apply to adjudications by agencies us

ing procedural formalities approximating those of courts.

In United States v. Utah Construction & Mining Co., 384

U.S. 394 (1966), this Court explicitly rejected the notion

that principles of issue preclusion do not apply to agency

adjudications:

When an administrative agency is acting in a judicial

capacity and resolves disputed issues of fact properly

before it which the parties have had an adequate

opportunity to litigate, the courts have not hesitated

to apply res judicata to enforce repose.

384 U.S. at 422. Applying this principle to the facts of

Utah, this Court concluded:

[T]he Board was acting in a judicial capacity . . .,

the factual disputes resolved were clearly relevant

to issues properly before it, and both parties had a

full and fair opportunity to argue their version of

the facts and an opportunity to seek court review

of any adverse findings. There is, therefore, neither

need nor justification for a second evidentiary hearing

on these matters already resolved as between these

two parties.

26

Id. This Court’s recognition that principles of issue pre

clusion are applicable to agency adjudications has been ex

tensively followed in the courts of appeals10 and was noted

recently by this Court in Kremer v. Chemical Construction

Corp., 456 U.S. 461, 485 n.26 (1982).

In this case, petitioners seek application of issue

preclusion11 to bar respondent’s attempt to relitigate

10. See, e.g., Pacific Seafarers, Inc. v. Pacific Far East

Line, Inc., 404 F.2d 804 (D.C. Cir. 1968), cert, denied, 393 U.S.

1093 (1969); Delamater v. Schweiker, 721 F.2d 50 (2d Cir.

1983); Gulf Oil Corp. v. FPC, 563 F.2d 588 (3d Cir. 1977), cert,

denied, 434 U.S. 1062 (1978); Pettus v. American Airlines, Inc.,

587 F.2d 627 (4th Cir. 1978), cert, denied, 444 U.S. 883 (1979);

Painters Dist. Council No. 38 v. Edgewood Contracting Co., 416

F.2d 1081 (5th Cir. 1969); International Wire v. Local 38, IBEW,

357 F. Supp. 1018 (N.D. Ohio 1972), affd, 475 F.2d 1078 (6th

Cir.), cert, denied, 414 U.S. 867 (1973); Bowen v. United States,

570 F.2d 1311 (7th Cir. 1978); United States v. Karlen, 645 F.2d

635 (8th Cir. 1981); United Farm Workers v. Arizona Agricul

tural Employment Relations Board, 669 F.2d 1249 (9th Cir. 1982);

McCulloch Interstate Gas Corp. v. FPC, 536 F.2d 910 (10th Cir.

1976).

Of particular significance here is the holding of the Ninth

Circuit in the United Farm Workers case that state agency adju

dications are entitled to full faith and credit in other states:

It is settled that if an administrative agency acts in a

judicial capacity, its judgments are entitled to recognition

and enforcement pursuant to the full faith and credit clause.

United States v. Utah Construction & Mining Co., 384 U.S.

394, 421-22, 86 S.Ct. 1545, 1559-1560, 16 L.Ed.2d 642

(1966). . . . The ultimate question in full faith and credit

analysis is one of res judicata. Thus, decisions of the courts

or administrative agencies of one state are entitled to the

same res judicata effect in all other states as they enjoy in

the state of rendition.

669 F.2d at 1255.

11. In Migra v. Warren City School District, 465 U.S. 75

(1983), this Court defined the terms “issue preclusion” and

“ claim preclusion” as follows:

Issue preclusion refers to the effect of a judgment in fore

closing relitigation of a matter that has been litigated and

decided. . . . This effect also is referred to as direct or

collateral estoppel. Claim preclusion refers to the effect

(C on tin u ed on fo llo w in g p a ge)

27

the very same issues fully and fairly litigated before

a state agency acting in a judicial capacity and with

the same procedural formalities as a federal or state

court. The fact that the Administrative Law Judge in

this case was not empowered to dispose of respondent’s

claims under the Reconstruction statutes in no way bars

application of full faith and credit to the issues actually

litigated and decided in the state proceeding. See Marrese

v. American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, ____ U.S.

....... , 105 S. Ct. 1327 (1985). The due process hearing con

ducted in this case was unquestionably a judicial proceed

ing of the State of Tennessee. The final agency judgment

with respect to issues actually litigated in the proceeding

is entitled, therefore, to the same full faith and credit

which it enjoys in Tennessee courts.

2. Denial Of Full Faith And Credit To The

Final Agency Judgment In This Case Would

Seriously Undermine The Integrity Of State

Agency Adjudications Conducted For The

Purpose Of Protecting Fourteenth Amend

ment Due Process Interests.

During the past fifty years, administrative agencies

at both the federal and state level have become essen-

Footnote continued—

of a judgment in foreclosing litigation of a matter that never

has been litigated, because of a determination that it should

have been advanced in an earlier suit. Claim preclusion

therefore encompasses the law of merger and bar.

Id. at 77 n.l.

Petitioners seek issue preclusion—not claim preclusion—in

this case and seek such preclusion without regard to which party

prevails in the prior adjudication. If, for example, respondent

had prevailed on the issue of racial discrimination, petitioners

maintain that the adjudication would bar petitioners from re

litigating that issue in a subsequent federal court action under

the Reconstruction statutes.

28

tially a fourth branch of government without which the

legislative, executive, and judicial branches could not func

tion adequately. In particular, the adjudicatory role of

administrative agencies has increased dramatically. As

Justice Jackson once stated: “The rise of administra

tive bodies probably has been the most significant legal

trend of the last century and perhaps more values today

are affected by their decisions than by those of all the

courts, review of administrative decisions apart.” FTC

v. Ruberoid Co., 343 U.S. 470, 487 (1952).

A significant increase in state agency adjudications

in recent years is particularly pronounced in the area

of public employment. In Board of Regents v. Roth, 408

U.S. 564, 569-70 (1972), this Court ruled that “ [w]hen

protected . . . [Fourteenth Amendment] interests are im

plicated, the right to some kind of prior hearing is para

mount.” Thus, any proposed action by state agencies

which threatens or even potentially threatens an employ

ee’s constitutionally protected liberty and property inter

ests triggers the requirement of an adjudication to protect

those interests. In Tennessee and thirty-one other juris

dictions which have adopted the Uniform Law Commis

sioners’ Model Administrative Procedures Act,12 an em-

12. See Ala. Code § 41-22-12 et seq. (1982); Ark. Stat.

Ann. § 5-709 (1976); Conn. Gen. Stat. Ann. § 4-177 (West Supp.

1985); Del. Code Ann. tit. 29, § 10121 et seq. (1983); D.C. Code

Ann. § 1-1509 (1981); Fla. Stat. Ann. § 120-57 (West 1982);

Ga. Code Ann. § 50-13-13 (1981); Hawaii Rev. Stat. § 91-9

(1976); Idaho Code § 67-5209 (1980); 111. Rev. Stat. ch. 27,

§ 1010 (1981); Iowa Code Ann. § 17A.12 (West 1978); La. Rev.

Stat. Ann. § 49:955 (West Supp. 1985); Me. Rev. Stat. Ann.

tit. 5, § 9051 et seq. (1979); Md. State Gov’t Code Ann. § 10-201

et seq. (1984); Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. § 24-24.271 et seq. (1981);

Mo. Ann. Stat. § 536.070 (Vernon Supp. 1985); Mont. Code Ann.

§ 2-4-601 et seq. (1979); Neb. Rev. Stat. § 84-913 et seq. (1981);

Nev. Rev. Stat. § 233B.121 et seq. (1981); N.H. Rev. Stat. Ann.

§ 541-A:16 (Supp. 1985); N.Y. Administrative Procedure Act

(C on tin u ed on fo llo w in g p a ge)

29

ployee is entitled to an adjudication virtually identical

to a civil trial in state or federal court. See Tenn. Code

Ann. §§ 4-5-301 through -323 (1985). Virtually every

judgment resulting from these formal adjudications could

be the subject of a collateral attack in federal court. When

an employee chooses, as respondent did in this case, to

invoke the trial-like proceedings of a state agency adjudica

tion to defend his liberty and property interests, the issues

fully litigated and decided there must be afforded full

faith and credit in federal courts in order to preserve

the integrity of the state adjudicatory process. Denial

of full faith and credit to the final state agency judgment

would render the process futile and seriously undermine

the role of state agency adjudication in resolving disputes

between public employers and employees.

The policies justifying preclusion—judicial economy,

reliance on adjudication, avoiding inconsistent results, re

lieving the parties of the cost and vexation of multiple

litigation—-as well as the policies of comity and federalism

supporting full faith and credit, are equally applicable

to agency adjudications and court adjudications. See gen

erally K. Davis, Administrative Law Treatise § 21:2

(1983); Restatement (Second) of Judgments § 83 (1982).

In this particular case, these policy considerations are

acutely implicated in view of respondent’s voluntary sub

mission of the issue of racial discrimination for adjudica

tion in the state agency, the protracted and costly nature

Footnote continued—

§ 301 et seq. (McKinney 1984) ; N.C. Gen. Stat. § 150A-23 et seq.

(1983); Okla. Stat. Ann. tit. 75, § 310 (West 1976); Or. Rev. Stat.

§ 183.413 et seq. (1985); R.I. Gen. Laws § 42-35-9 (1984); S.D.

Comp. Laws Ann. § 1-26-16 et seq. (1980); Vt. Stat. Ann. tit. 3,

§ 809 (1972); Wash. Rev. Code Ann. § 34.04.090 et seq. (1965);

W.Va. Code § 29A-5-1 et seq. (1980); Wis. Stat. Ann. § 227.07

(West 1982); Wyo. Stat. § 16-3-107 (1982).

30

of the adjudication, and the state’s interest in pre

serving the integrity of its contested case adjudications.

As this Court stated in Baldwin v. Iowa State Traveling

Men’s Ass’n, 283 U.S. 522, 525-26 (1931):

Public policy dictates that there be an end of liti

gation; that those who have contested an issue shall

be bound by the result of the contest and that matters

once tried shall be considered forever settled as be

tween the parties. We see no reason why this doc

trine should not apply in every case where one vol

untarily appears, presents his case and is fully heard,

and why he should not, in the absence of fraud, be

thereafter concluded by the judgment of the tribunal

to which he has submitted his cause.

The public policies embodied in traditional principles of

full faith and credit dictate that this litigation come to

an end and that respondent be precluded from relitigating

issues he voluntarily submitted for full adjudication in

the state agency.13

13. According full faith and credit to state agency adjudi

cations in subsequent civil rights actions under the Reconstruc

tion statutes is in no way dependent upon resolution of the

Title VII question also presented in this case. The contrary

opinion of the Sixth Circuit completely ignores this Court’s re

peated admonitions that the Reconstruction statutes and Title

VII provide separate, distinct, and independent avenues of

relief for alleged employment discrimination. See, e.g., Johnson

v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421 U.S. 454 (1975); Alexander

v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36 (1974).

The Reconstruction statutes and Title VII differ markedly

in terms of coverage, preconditions to a federal court action,

applicable limitations period, and relief available upon proof

of a violation. See generally 2 J. Cook & J. Sobieski, Civil Rights

Actions HIT 4.09, 5.04, 7.04 (1985). Moreover, the Reconstruction

statutes are certainly not restricted to claims of alleged employ

ment discrimination. Yet, only in the area of employment dis

crimination can any argument be made for identical full faith

and credit treatment under the Reconstruction statutes and Title

(C on tin u ed on fo llo w in g p age)

31

II. TRADITIONAL PRINCIPLES OF FULL FAITH

AND CREDIT APPLY IN TITLE VII ACTIONS

TO ISSUES FULLY AND FAIRLY LITIGATED

SOLELY AT THE INSISTENCE OF THE AG

GRIEVED EMPLOYEE BEFORE A STATE

AGENCY ACTING IN A JUDICIAL CAPACITY

OUTSIDE THE TITLE VII ENFORCEMENT

SCHEME.

A. Title VII Actions Are Not Categorically Ex

empt From Traditional Principles Of Full

Faith And Credit.

In Kremer v. Chemical Construction Corp., 456 U.S.

461 (1982), this Court held that traditional principles of

full faith and credit apply to state court judgments in

subsequent Title VII actions. After a careful review of

the language and legislative history of Title VII, this Court

expressly rejected the notion that Congress intended to

create an absolute right to relitigate in federal court issues

resolved by a state court. On the contrary, finding that

Congress did not intend that Title VII supersede the prin

ciples of comity and repose embodied in the full faith

and credit statute, this Court concluded that full faith

and credit applies to a state court judgment affirming,

without de novo review, the findings of a Title VII state

deferral agency.

Footnote continued—

VII. To do so would lead to the anomalous result that different

claims arising under the Reconstruction statutes-—conceivably

involving the very same factual context—would be subject to

radically different preclusion effect, notwithstanding the absence

of any indication in the Reconstruction statutes that such a dis

tinction should be made. Id. at H 5.04.

32

B. No Provision Of Title VII Required Respon

dent To Litigate The Issue Of Racial Discrim

ination In The State Agency Proceeding; Nor

Does Any Provision Of Title VII Specify The

Effect Of The Final Agency Judgment.

A principal teaching of this Court’s decision in Kremer,

as well as Allen and Migra, is that an exception to full

faith and credit “will not be recognized unless a later

statute contains an express or implied partial repeal.”

Kremer, 456 U.S. at 468. Because there can be no claim

that Title VII expressly repeals the full faith and credit

statute, any repeal must be implied. As stressed in Allen,

Migra, and Kremer, however, repeals by implication are

not favored. See Kremer, 456 U.S. at 468. Indeed, in

Kremer this Court recognized only two well-established

categories of repeal by implication: (1) where the pro

visions of two acts are in irreconcilable conflict; and (2)

where a later act covers the entire subject of an earlier

one and clearly is intended as a substitute. See id.

Considering the relationship between Title VII and

the full faith and credit statute with respect to a state

court judgment, this Court emphasized in Kremer that

“ [n]o provision of Title VII requires claimants to pursue

in state court an unfavorable state administrative action,

nor does the Act specify the weight a federal court should

afford a final judgment by a state court if such a remedy

is sought.” Kremer, 456 U.S. at 469. Finding no clear

and manifest incompatability, therefore, between Title

VII and the full faith and credit statute, this Court con

cluded that nothing in the language or operation of Title

VII impliedly repeals the statutory mandate of full faith

and credit.

33

This case presents an even more compelling circum

stance than Kremer for finding no repeal by implication

of the statutory command of full faith and credit. Nothing

in Title VII obligated respondent to litigate the issue

of racial discrimination in the state forum. Respon

dent did not invoke the state proceedings pursuant to

a state antidiscrimination law.14 Rather, exercising his

right as a public employee to defend his liberty and prop

erty interests under the Fourteenth Amendment, respon

dent invoked a due process hearing under the Tennessee

Uniform Administrative Procedures Act to challenge his

proposed termination. Once invoked, the Act required

the University to afford respondent a formal, trial-like

hearing. Respondent fully litigated the issue of racial

discrimination in the due process hearing as an affirmative

defense to the disciplinary charges against him. Respon

dent thus made a critical choice to litigate the issue of

racial discrimination outside the Title VII enforcement

scheme. Nothing in Title VII or any other provision of

law required him to do so.

Moreover, nothing in Title VII purports to specify

the effect a federal court should afford the final agency

judgment in this case. Title VII only specifies that the

EEOC must afford “substantial weight” to the findings

of state agencies which are charged with the enforcement

14. Title VII requires deferral only to those state agencies

which by state law are empowered “ to grant or seek relief from”

the alleged unlawful employment practice. See 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-5(c), (d) (1982). In Tennessee, the required deferral

agency is the Tennessee Human Rights Commission, which is

authorized by the provisions of Tenn. Code Ann. § 4-21-202

(1985) to enforce the state’s law against employment discrimina

tion.

34

of state antidiscrimination laws.15 This provision could

be construed, therefore, as an implied repeal of the full

faith and credit statute only as it applies to determinations

by Title VII deferral agencies. See Kremer, 456 U.S. at

470 n.7. No provision of Title VII prescribes the effect

of a state agency adjudication voluntarily invoked by an

aggrieved employee outside the Title VII enforcement

scheme, and thus nothing in Title VII can be construed as

an implied repeal of the full faith and credit due such an

adjudication.

As established earlier with respect to respondent’s

action under the Reconstruction statutes, see pp. 22 to

30 supra, full faith and credit applies to prior state judi

cial proceedings whether conducted by a state court or

by a state agency acting in a judicial capacity. This

Court’s decision in Kremer unquestionably establishes that

federal courts must apply full faith and credit principles

in Title VII actions unless Title VII itself impliedly repeals

the statutory command. Because nothing in Title VII re

quired respondent to invoke the state proceeding con

ducted in this case or to litigate the issue of racial dis

crimination there, and because nothing in Title VII spec

ifies the effect of the resulting judgment, nothing in the

language or operation of Title VII can in any way be

viewed in this case as an express or implied repeal of

the statutory mandate of full faith and credit. Nothing

15. The provision of Title VII requiring the EEOC to give