Affidavit in Support of Motion for Admission Pro Hac Vice

Public Court Documents

October 7, 1992

3 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Sheff v. O'Neill Hardbacks. Affidavit in Support of Motion for Admission Pro Hac Vice, 1992. 8dc0bb01-a346-f011-877a-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/54164d09-7075-4f00-b655-a00693a24f38/affidavit-in-support-of-motion-for-admission-pro-hac-vice. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

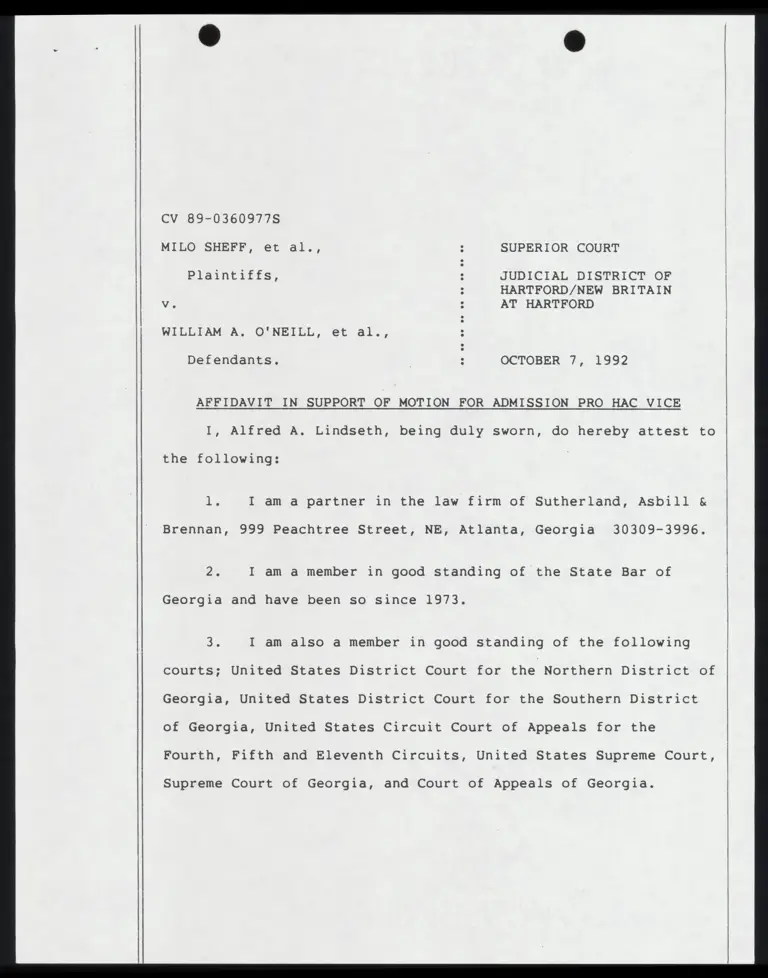

CV 89-03609717s

MILO SHEFF, et al,, SUPERIOR COURT

Plaintiffs, JUDICIAL DISTRICT OF

HARTFORD/NEW BRITAIN

Vv. AT HARTFORD

WILLIAM A. O'NEILL, et al.,

Defendants. OCTOBER 7, 1992

AFFIDAVIT IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR ADMISSION PRO HAC VICE

I, Alfred A. Lindseth, being duly sworn, do hereby attest to

the following:

: 4 I am a partner in the law firm of Sutherland, Asbill &

Brennan, 999 Peachtree Street, NE, Atlanta, Georgia 30309-3996.

2. I am a member in good standing of the State Bar of

Georgia and have been so since 1973.

3. I am also a member in good standing of the following

courts; United States District Court for the Northern District of

Georgia, United States District Court for the Southern District

of Georgia, United States Circuit Court of Appeals for the

Fourth, Fifth and Eleventh Circuits, United States Supreme Court,

Supreme Court of Georgia, and Court of Appeals of Georgia.

4, There are no grievances pending against me, nor have I

ever been reprimanded, suspended, placed on inactive status,

disbarred, or have I ever resigned from the practice of law.

The foregoing statements are true and accurate to the best

of my knowledge and belief.

Alfred/A. Lindseth, Affiant

Subscribed and sworn to befoye me this 7th day of October,

1992,

» R. Whelan

issioner of the Superior Court

Respectfully submitted in/support of the request for

admission in Pro Hac Vice on file in the above-captioned case.

FOR THE DEFENDANTS,

RICHARD BLUMENTHAL

ATTORNEY GENERAL

BY:

: 2

Jon R. Whelan - Juris No. 085112

Agsistant Attorney General

110 Sherman Street

/ Hartford, CT 06105

Tel: 566-7173

CERTIFICATION

This is to certify that on this 7th day of October, 1992 a

copy of the foregoing was mailed to the following counsel of

record:

John Brittain, Esq.

University of Connecticut

School of Law

65 Elizabeth Street

Hartford, CT 06105

Philip Tegeler, Esq.

Martha Stone, Esq.

Connecticut Civil

Liberties Union

32 Grand Street

Hartford, CP -06105

Ruben Franco, Esq.

Jenny Rivera, Esq.

Puerto Rican Legal Defense

and Education Fund

99 Hudson Street

14th Floor

New York, NY 10013

John A. Powell,

Helen Hershkoff, Esq.

Adam S. Cohen, Esq.

American Civil Liberties Union

132 West 43rd Street

New York, NY 10036

Esq.

wilfred Rodriguez, Esq.

Hispanic Advocacy Project

Neighborhood Legal Services

1229 Albany Avenue

Hartford, CT 06112

Wesley W. Horton, Esq.

Moller, Horton &

Fineberg, P.C.

90 Gillett Street

Hartford, CT 06105

Julius L. Chambers,

Marianne Lado, Esq.

Ronald Ellis, Esq.

NAACP Legal Defense Fund and

Education Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

Esq.

Ad

Johh R. Whelan

V4

po Attorney General