Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

March 10, 1997

36 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Campaign to Save our Public Hospitals v. Giuliani Hardbacks. Appellants' Brief, 1997. 9a03b44a-6835-f011-8c4e-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/543e6be1-8551-4639-99f3-29415baadc04/appellants-brief. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

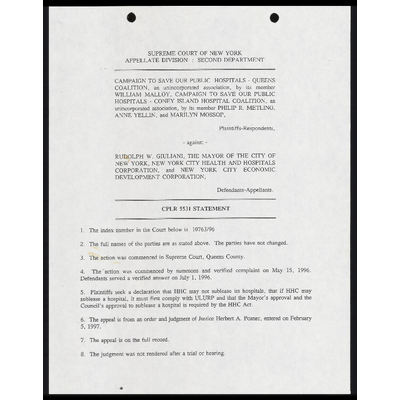

SUPREME COURT OF NEW YORK

APPELLATE DIVISION : SECOND DEPARTMENT

CAMPAIGN TO SAVE OUR PUBLIC HOSPITALS - QUEENS

COALITION, an unincorporated association, by its member

WILLIAM MALLOY, CAMPAIGN TO SAVE OUR PUBLIC

HOSPITALS - CONEY ISLAND HOSPITAL COALITION, an

unincorporated association, by its member PHILIP R. METLING,

ANNE YELLIN, and MARILYN MOSSOP,

Plaintiffs-Respondents :

- against -

RUDOLPH W. GIULIANI, THE MAYOR OF THE CITY OF

NEW YORK, NEW YORK CITY HEALTH AND HOSPITALS

CORPORATION, and NEW YORK CITY ECONOMIC

DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION,

Defendants-Appellants.

CPLR 5531 STATEMENT

1. The index number in the Court below is 10763/96

2. The full names of the parties are as stated above. The parties have not changed.

3. The action was commenced in Supreme Court, Queens County.

4. The action was commenced by summons and verified complaint on May 15, 1996.

Defendants served a verified answer on July 1, 1996. :

5. Plaintiffs seek a declaration that HHC may not sublease its hospitals, that if HHC may

sublease a hospital, it must first comply with ULURP and that the Mayor's approval and the

Council's approval to sublease a hospital is required by the HHC Act.

6. The appeal is from an order and judgment of Justice Herbert A. Posner, entered on February

5, 1997.

7. The appeal is on the full record.

8. The judgment was not rendered after a trial or hearing.

SUPREME COURT OF NEW YORK

APPELLATE DIVISION : SECOND DEPARTMENT

CAMPAIGN TO SAVE OUR PUBLIC HOSPITALS - QUEENS

COALITION, an unincorporated association, by its member

WILLIAM MALLOY, CAMPAIGN TO SAVE OUR PUBLIC

HOSPITALS - CONEY ISLAND HOSPITAL COALITION, an

unincorporated association, by its member PHILIP R. METLING,

ANNE YELLIN, and MARILYN MOSSOP,

Plaintiffs-Respondents,

- against -

RUDOLPH W. GIULIANI, THE MAYOR OF THE CITY OF

NEW YORK, NEW YORK CITY HEALTH AND HOSPITALS

CORPORATION, and NEW YORK CITY ECONOMIC

DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION,

Defendants-Appellants.

APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

The New York City Health and Hospitals Corporation ("HHC") has taken an important

step to adapt to the rapid changes currently sweeping the world of health care; it has approved

leasing one of its hospitals to a private company, PHS-NY. The sublease of Coney Island

Hospital is a privatization that will improve services for patients and increase the efficiency of

the institution, while maintaining access to health care for indigent uninsured people.

Under the sublease, PHS-NY has committed to a level of charity care greater than what

HHC provides today, to keep the hospital as a community based, acute care inpatient hospital

with a broad range of services, to improve the hospital’s physical plant immediately with a to

the outstanding debt associated with Coney Island Hospital, thereby freeing HHC borrowing

capacity for other HHC projects. HHC has retained significant oversight and enforcement

powers to ensure that the sublease obligations are carried out.

The lower court held that HHC was precluded from taking this step. It interpreted the

HHC Act as freezing the City’s health care facilities in the configuration they had during the

Lindsay Administration, barring any adaptation to current conditions, the needs of the patient

population and the state of the health care industry. Further, even if any changes could be made,

the lower court would revert to the days of the City’s Department of Hospitals and require the

Health and Hospitals Corporation to comply with the red tape that binds decision making ny Cli;

agencies.

This was wrong on both counts. The State Legislature has explicitly granted HHC the

authority to lease out its hospitals. Further, the Legislature created HHC as an independent

entity precisely in order that the City could act on health care issues without being subjected to

paralyzing layers of bureaucracy and review. The lower Court’s holding that HHC leases are

subject to the City’s Uniform Land Use Review Procedure and oboesval by the City Council is

therefore not only judicial legislation, it is contrary to the Legislature's stated intentions in

creating the Health and Hospitals Corporation.

By this appeal, defendants ("the City") seek to reverse the judgment of the Supreme

Court, Queens County (Posner, J.), entered February 5, 1997, which declared that (1) the HHC

Act precludes the lease of HHC hospitals, (2) HHC must follow the New York City Charter

Uniform Land Use Review Process, and (3) HHC leases have to be approved by the City

Council in addition to the Mayor.

Council v. Giuliani was litigated together with Campaign to Save Our Public Hospitals-

Queens Coalition v. Giuliani. The lower Court partially consolidated the two actions and issued

one consolidated opinion. The Court entered separate judgments with identical decretal

paragraphs. Accordingly, the City is submitting the same appellants’ brief in these two appeals

and, by separate motion, has requested that the appeals be consolidated for the purpose of

argument.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. The HHC Act authorizes HHC to sell, lease or sublease hospital facilities. Does this

specific grant of authority allow HHC to sublease Coney Island Hospital?

2. ULURP does not apply to HHC property and HHC was created for the purpose of

freeing the municipal hospital system from red tape and excessive review processes. Should

ULURP be nonetheless applied to this sublease of HHC’s leasehold?

3. The HHC Act provides that HHC leases must be consented to by the "Board of

Estimate." Does the City Council succeed to the Board’s power to consent to real property

transactions, when under the New York City Charter the Mayor succeeded to the Board of

Estimate in consenting to real property dispositions, the Council has no role in land use issues

outside of ULURP and all non-delegated powers reside with the Mayor?

STATEMENT OF FACTS

The health care environment in New York is changing rapidly and the New York City

Health and Hospitals Corporation ("HHC") has had to adapt along with it in order to continue

to provide health care services for poor New Yorkers. This appeal concerns one avenue of

-

change proposed by Mayor Giuliani and adopted after considerable review and debate by the

HHC Board of Directors: the privatization of Coney Island Hospital.

The Health Care Revolution and Privatization

HHC has been severely affected by the massive changes in the health care industry.

Trends including the cost controls imposed under managed care contracts, reduced governmental

reimbursement for charity care and the movement toward outpatient services have hurt HHC’s

ability to provide access to health care services for all, regardless of ability to pay. With the

City facing long term and significant financial constraints, HHC has found it Horessingly

difficult to make necessary physical improvements to antiquated facilities and to provide a full

range of quality health care services (Co 42-43; Ca 169).

For the first time, HHC is losing its traditional patient base. With the rise of managed

care and HMO'’s, individuals eligible for Medicaid benefits have become financially attractive

to private sector health care providers. Poor people who have a choice are turning away from

HHC hospitals and entering private hospitals (Co 42-43; Ca 169). A study by the Health

Systems Agency of New York City noted that between 1989 and 1992, 92% of new Medicaid

admissions were to voluntary hospitals (Co 530-31; Ca 527-28).

In light of the changing dynamics of health care, the Giuliani Administration proposed

that New York City investigate the possibility of selling or leasing hospitals (Co 42-43; Ca 169).

As part of a City-wide examination of possible asset privatizations undertaken by the City’s

Economic Development Corporation ("EDC"), the City engaged the firm of J.P. Morgan to

I Citations preceded by “Co” are to the Record on Appeal in the Council case. Citations

preceded by “Ca” are to the Record on Appeal in the Campaign case.

de

analyze several HHC hospitals and determine whether privatization was achievable in New York

City (Co 42-43; Ca 161).

In brief, the Report found that privatization of three hospitals: Coney Island Hospital,

Queens Hospital Center and Elmhurst Hospital Center, would improve the quality of health care

for patients and save HHC and the City substantial sums of money. The Report found that the

hospitals would likely do better outside of HHC because their financial and operating

performance were inferior to that of surrounding voluntary hospitals. For example, Coney Island

Hospital had a negative return of 7.33% while private hospitals in the same service oro

generated positive earnings of between 6.44% to 8.27% (Ca 177-78). In 1994, Coney Island

Hospital lost $11,743,000 before interest, depreciation and amortization, excluding the City

operating subsidy (Ca 180-82). Because of the negative cash flow, Coney Island Hospital was

unable to fund current capital projects or even fund normal maintenance and reconstruction.

Queens Hospital Center and Elmhurst Hospitals Center were in similar condition (Co 43; Ca

161).

The strict requirements for privatization

Offering Memoranda were circulated for both Coney Island Hospital and Queens Hospital

Center jointly with Elmhurst Hospital Center ("Queens Health Network"). No proposal

concerning the Queens Health Network ever reached the stage of consideration by the HHC

Board. Accordingly, this brief will describe only the Coney Island Hospital transaction.

The Offering Memorandum for Coney Island Hospital set rigorous conditions to ensure

that any private entity that subleased the hospital would continue to provide quality health care.

The requirements included provisions for indigent and charity care, continuation of all important

health care services, and a commitment to making a substantial capital investment in the hospital.

(Co 229-30, 531; Ca 528).

Regarding the indigent care obligation, the Offering Memorandum for Coney Island

Hospital explained (Co 107-08; Ca 87-88):

The City and HHC are committed to preserving and

improving the ability of all New Yorkers to access

quality care, including those who may not have the

financial resources to pay and who are not covered by

third party reimbursement (Medicare, Medicaid, Blue

Cross, private insurance, or a managed care plan). The

City and HHC expect any prospective purchaser of CIH

will develop and maintain clinics, community-based

programs, and other means of primary care access to

care for all residents, including the indigent, at levels

at least equal to the care already being received. . . .

Three entities expressed an interest in subleasing Coney Island Hospital but only one,

Primary Health Systems New York, Inc. ("PHS-NY"),? was willing to meet all the terms of the

Offering Memorandum (Co 48; Ca 28). PHS agreed to continue indigent care at the hospital

without a City subsidy, to satisfy all outstanding hospital debt and to operate the hospital

immediately once it received the necessary State approvals. PHS planned to improve Coney

Island Hospital by recruiting community doctors to increase the pool of physicians who admit

patients to the hospital, joining local networks, establishing up to five new community outpatient

2 PHS-NY was established by two key employees of a private hospital company, Primary Health

Systems, Inc ("PHS, Inc."). Public Health Law § § 2801-a(4)(e), 2801-a(9)(b) provide that a

for-profit corporation may be licensed to own and operate a hospital only if all of its

shareholders are individuals. PHS, Inc. has or may have in the future one or more corporate

shareholders. Therefore, PHS-NY will be able to apply for State approval to own and operate

Coney Island Hospital (Co 396; Ca 399). PHS-NY intends to enter into a management

agreement with PHS, Inc. for Coney Island Hospital. In this brief, defendants will refer to both

entities as "PHS".

facilities and expanding outreach programs in schools and senior centers. PHS also planned to

rehabilitate the hospital's physical plant by reducing the number of beds in a room from six to

a maximum of four and providing a bathroom, with shower for each patient room, upgrading the

heating, ventilation and air conditioning systems, and creating a computerized information system

that would be accessible throughout the hospital and in the offices of affiliated doctors (Co 536-

37; Ca 531b-c).

After months of negotiations, HHC and PHS agreed on the terms of the sublease and it

was submitted to the HHC Board for approval on October 24, 1996 (Co 393; Ca 396). | The

HHC Board approved the sublease on November 8, 1996 (Co 590; Ca 582). The parties

anticipate closing on the sublease after all State approvals have been obtained, a labor agreement

has been reached,’ PHS has obtained the necessary financing and the litigation challenging the

sublease has been satisfactorily resolved (Co 396-97; Ca 349-400).

3 The unions have brought unfair labor practice proceedings against the City before the New

York City Board of Collective Bargaining concerning the decision to privatize: E.g. DC 37 v.

Citv of New York, Docket No. BBB-1837-96.

4 The Campaign plaintiffs joined with three members of the HHC Board of Directors in Jones

v. The Citv of New York, N.Y. Co. Index No. 117768/96 (Gangel-Jacob, J .), to claim that the

HHC Board had insufficient information before approving the sublease of Coney Island Hospital

and that the sublease violated the laws and rules governing procurement. The Jones plaintiffs

first sought, but withdrew, an application for a temporary restraining order enjoining the HHC

Board vote approving the sublease. The City has moved for summary judgment in Jones and

plaintiffs have moved for partial summary judgment on the issue of whether the Board had

sufficient information before it approved the sublease. Neither motion has been decided and,

by order dated February 4, 1997, the Court temporarily struck the case from the calendar

pending resolution of this appeal.

A related proceeding, Commission on Public’s Health Systems v. HHC, N.Y.Co. Index

No0.103242/97 (Gangel-Jacob, J .), challenging the environmental review of the proposed sublease

was filed by various groups including the Campaign plaintiffs on February 27,1997.

the

The terms of the sublease of Coney Island Hospital

The. entire sublease is included in the Record at Co 401-470aa; Ca 404-473aa. The most

important terms are summarized here for the Court’s convenience:

Charity Care: For the life of the sublease, PHS will offer care without regard to ability to pay

up to a level 115% greater than the charity care expense currently carried by HHC at Coney

Island Hospital. Any available third party reimbursements (including reimbursement from the

State pools) will not be counted towards PHS’ charity care obligation. Further, the base figure

will be indexed to a medical inflation rate. The charity care obligation will be Ssrniodd by

PHS, Inc. If charity care expenses in a given year rise over the 115% level, HHC will

reimburse PHS for the excess expense for one year.” After that year and through every

subsequent year of the sublease, PHS will continue to offer up to 115% of HHC’s charity care

cost.

Continuation of Services: PHS will continue to provide in-patient and out-patient programs in

"all core service areas offered at Coney Island Hospital as of the day before the closing. The

core service areas include all services currently provided as a matter of course by a community

hospital including medicine, general surgery, pediatrics, ob/gyn, rehabilitation, psychiatry and

emergency medicine.

Capital Commitment: PHS will spend at least $25 million in the first five years of the sublease

on capital projects at Coney Island Hospital, in addition to assuming all routine maintenance

costs (estimated at $5 million per year).

5 The City has agreed to reimburse HHC for that one year payment (Ca 621).

3

Assumption of Bond Indebtedness: PHS will pay approximately $49 million for the sublease,

an amount. representing the outstanding HHC and City bonds associated with Coney Island

Hospital, thereby freeing HHC borrowing capacity for other capital projects.

Assumption of Liability: PHS will assume all liability for using and operating the hospital,

including malpractice liability, currently a $6 million per year expense to the City.

Monitoring of Compliance: HHC will have the right to audit PHS’s books and records.

Regarding the obligations for charity care and continuation of services, the parties agree to

arbitration by a health care expert, a special monitor, specific performance of service Sbiiziedl

and, in the event of a default on the charity care obligation, specific performance, damages and

termination of the lease. In addition, the hospital will have a community advisory board, which

will develop a grievance process and PHS will provide public report cards.

Public briefing

Senior HHC management officials regularly briefed all interested bodies regarding

privatization plans and distributed the Offering Memoranda once they were completed. Briefings

and reports were given to the HHC Board of Directors, representatives of the City Council, the

office of the Queens and Brooklyn Borough Presidents, and the hospitals’ Community Advisory

Boards (Co 44-45; Ca 25-26).

Early on in the process, the Queens Hospital Center Community Advisory Board sued

claiming that HHC was affording it insufficient participation in privatization planning. The claim

was dismissed, the Appellate Division, First Department, finding that "HHC had, to date,

undertaken reasonable, appropriate efforts to inform QHCCAB of the status of the privatization

planning efforts." Queens Hospital Center Community Advisory Board v. HHC, Index No.

12374/95 (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Co.), aff'd _A.D.2d _, 642 N.Y.S.2d 236 (Ist Dept. 1996), lv. app.

den., 88 N.Y.2d 814 (1996).

The briefing process continued after the Offering Memoranda had been completed. As

the President of HHC, Dr. Luis Marcos, explained in an affidavit submitted to the Court below,

at virtually every regularly scheduled meeting of the hospitals’ Community Advisory Boards

(“CAB”), an HHC representative provided updates or was available to answer questions on

privatization. In November, 1995, Maria Mitchell, then the HHC Chairperson, testified at a fact

finding hearing on privatization held by the Brooklyn Borough Présiden and the Coney A

Hospital CAB. In February and March, 1996, HHC organized focus group sessions to work out

proposals for monitoring access to health care by the indigent following privatization, with

members selected by the hospitals’ executive directors, Community Advisory Boards and the

local Community Boards (Co 45; Ca 25).

Once HHC had preliminarily agreed to negotiate a sublease with PHS, the President of

HHC signed a Letter of Intent with PHS setting out the terms that the sublease would include.

The Letter of Intent was widely distributed to the public, including the Brooklyn Borough

President’s Office and the Chair of the affected Community Board (Co 48; Ca 28).

As required by the HHC Act and New York City Charter § 556(m), HHC and the New

York City Department of Health held a joint public hearing on the proposed sublease of Coney

Island Hospital at the hospital on October 8, 1996. Before the hearing, an abstract of the terms

and conditions of the sublease was distributed to the public. The sublease was restructured as

a result of this public hearing to respond to requests for additional community representation on

the hospital’s community advisory board. (Co 399; Ca 402).

-10-

The HHC Board review

The HHC Board held two public sessions to consider the sublease. The Board discussed

at length the merits of privatization, the likely impact of the sublease on care for the poor and

uninsured, whether PHS was an appropriate company to take over Coney Island Hospital, PHS’

financial strength, the quality of medical care at PHS run hospitals in other cities, and how HHC

oversight of the hospital would work. The Board was briefed on every aspect of the sublease

including its terms (Co 398; Ca 401), HHC staff site visits to PHS hospitals in Cleveland (Co

481; Ca 484), the PHS capital program for Coney Island Hospital (Co 537; Ca 536c), and bond

counsel’s advice regarding the financing of the sublease (Co 510; Ca 510).

The Board also received a lengthy report on the health care and environmental impacts

of the sublease (Co 517; Ca 517). The consultants projected that under the sublease the poor

and uninsured would be more likely to receive health care services at Coney Island Hospital than

if HHC remained in control of the hospital (Co 565-66; Ca 556-57). The HHC Board approved

the sublease on November 8, 1996 (Co 589; Ca 582).

State review of the sublease

"Before PHS can take over Coney Island Hospital, the PHS proposal is subject to

extensive State regulatory review. The State must first determine whether to approve the

establishment of Coney Island Hospital under PHS management and control. This application

will be reviewed by DOH, the State Hospital Review and Planning Council and the Public Health

Council ("PHC"). These bodies will review whether PHS has offered a "substantially consistent

high level of care" at its hospitals in the past, whether Coney Island Hospital will have a

satisfactory financial plan and the resources to stay in operation, whether the principals of PHS

have the character and competence to operate a high quality hospital, and such other matters as

the PHC deems pertinent. Public Health Law § 2801-a[3]. PHS must also secure an operating

certificate from DOH pursuant to Public Health Law § 2805. PHS will have to show that the

hospital care is "fit and adequate" and that it will operate the hospital in accordance with law.

Public Health Law § 2805(2) (b).

The present litigation

The New York City Council initiated the present action in March 1996 and the Campaign

to Save Our Public Hospitals ("Campaign") filed suit in May (Co 51; Ca 63). Both laintiffs

sought a declaration that the City’s Uniform Land Use Review Procedure ("ULURP") applied

to leases of HHC property. The Council plaintiffs also sought a declaration that the Council and

the Mayor jointly succeeded to the Board of Estimates role in approving leases under the HHC

Act. Plaintiffs sought a permanent injunction barring the sublease of the hospitals until these

steps were complied with.°

After the sublease of Coney Island Hospital had been approved by the HHC Board, the

lower Court invited the parties to address the argument of whether it was ultra vires for HHC

to sublease a hospital under any circumstances (Co 599). Plaintiffs subsequently amended their

complaints to raise this claim as well (Co 605; Ca 830).

By order and judgment entered February 5, 1997, the lower Court granted plaintiffs

summary judgment and declared (1) that the HHC Act barred HHC from subleasing a hospital;

6 In addition, the Council plaintiffs argued that the sublease violated General City Law § 23(b),

which requires sale of the City’s real property to the highest bidder, and the Campaign plaintiffs

argued that information regarding use of City owned land was not presented to Community

Boards pursuant to Charter § 197-b. The lower Court did not find for plaintiffs on either claim,

which will not be addressed in this brief.

(2) that an HHC lease is subject to ULURP; and, (3) that both the City Council and the Mayor

must approve the lease of an HHC hospital under the HHC Act.

OPINION BELOW

The Court found that HHC could not privatize its hospitals. The Court agreed that the

HHC Act authorized HHC to sublease its hospitals to a private hospital company but concluded

that the law could not mean what it says (Co 637; Ca 861):

HHC, by contracting with PHS-NY by means of a

99 year sublease, to have PHS-NY take over the

operation of CIH, is shirking its own statutorily

imposed responsibility, without the Legislature's

approval. Although the HHC Act concededly allows

for provision of health and medical services “by

agreement or lease with any person firm or private

or public corporation or association, through and in

the health facilities of [HHC] and to make rules and

regulations governing admissions and health and

medical services” (McKinney’s Uncons Laws § 7385

[8]), such allowance may not be construed to permit

the incongruous result that HHC can delegate or

shift all of its responsibilities to a non-public entity

as a means of “furthering its corporate purposes.”

(McKinney's Uncons Law § 7385 [8]). Moreover,

that reading would frustrate the purposes and

obligations of the HHC to the people of the City....

Instead, based on press reports that Mayor Giuliani supported privatization because he

believed that municipally owned hospitals will not long survive, the Court concluded that HHC

was trying to eliminate all of its hospitals and put itself out of existence (Co 638-39; Ca 862-63):

The evidence presented on these motions makes it

clear that defendants seek to privatize all the HHC

hospitals. It is also obvious that the “turning over”

of CIH to a non-public corporation, is the first step

towards defendants’ ultimate goal of disengaging the

City from the municipal hospital system and placing

municipal hospital services in the hands of an

13-

outsider or the private sector. At the least,

defendants seek to “downsize” HHC and minimize

its role (and therefore the City’s role), for an

examination of the sublease terms reveals such

limited retained control by HHC as to raise the

question of whether HHC's continued existence

could be justified if such subleasing is repeated in

connection with the other HHC hospitals.

The Court concluded that by subleasing Coney Island Hospital HHC was abandoning its

mission, rather than trying to fulfill its mission by a creative response to rapid changes in the

health care environment (Co 639; Ca 863):

The history of the creation of HHC is instructive.

HHC was borne out of the City’s need to salvage a

hospital system that was floundering. If HHC

likewise is confronted with a system nearly

drowning in red ink, defendants’ response cannot be

simply to jump ship. They must go back to the

Legislature, and seek an amendment or repeal of the

HHC Act, or devise some other plan for managing

the crisis.

In dicta rendered unnecessary by its conclusion that privatization was barred, the Court

also found that HHC leases are subject to ULURP. Ignoring the fact that HHC was only

subleasing its own leasehold, not the City’s fee, the Court found that HHC is subject to ULURP

(Co 634; Ca 858):

E1

Defendants alternatively contend ULURP is

inapplicable because the sublease of CIH is not the

subject of any disposition by the City, but instead,

a disposition by HHC. They argue that under

traditional notions of property law, a lessee is free

to exercise possession and control over the property

as against the world, including the landlord.

According to defendants, HHC is legally allowed to

sublease, and to require it to undergo ULURP

review would render its leasehold less significant.

Charter § 197-c, however, is not restricted to

-14-

dispositions by the City, but instead, is applicable to

any dispositions of the real property of the City.

Even though the HHC Act, as State law, should pre-empt ULURP’s applicability and

even though ULURP did not exist when the HHC Act was adopted in 1967, the Court also found

a State intention to subject HHC to ULURP (Co 634; Ca 858): "[I]t is the HHC Act itself

which grants a check on HHC’s authority to dispose of real property, albeit via the Board of

Estimate, now a nonexistent body."

The Court also concluded that the Mayor and the City Council jointly succeeded to the

Board of Estimate’s role of consenting to HHC leases under the HHC Act. The Court reasoned

that the Board of Estimate might have weighed both the business terms of a lease and its land

use effects in exercising its HHC Act powers (Co 629; Ca 853). Then, the Court explained, that

since the Council succeeded to the Board's land use powers under ULURP, the Council and the

Mayor jointly succeed to the Board of Estimate’s approval role under the HHC Act (Co 630; Ca

854).

-15-

POINT ONE

. THE HHC ACT AUTHORIZES THE SUBLEASE OF CONEY

ISLAND HOSPITAL TO A PRIVATE COMPANY.

The powers of the Health and Hospitals Corporation are established by the New York

City Health and Hospitals Corporation Act ("HHC Act"), which created HHC. Unconsol. Laws

§§ 7381 et seq. The HHC Act was written with the express intention of allowing HHC

flexibility to structure the delivery of medical services to the poor and uninsured. The

Legislature gave HHC broad powers to carry out its mandate, including explicit authorization

to sell, lease or sublease hospitals to private companies. Accordingly, the lower Court’s

declaration that the sublease of Coney Island Hospital was ultra vires is both directly contrary

to the language of the governing statute and to its spirit.

The HHC Act explicitly grants HHC the authority to sublease its hospitals to a private

company in section 7385. HHC is given broad powers under section 7385 [6] to sublease

hospitals:

The corporation shall have the following powers in

addition to those specifically conferred elsewhere in

this act:

[6] to dispose of by ...lease or sublease, real ...

property, including but not limited to a health

facility, or any interest therein for its corporate

purposes .

7 Unconsol. Law § 7385 [6] states in its entirety that HHC has the power: “To acquire, by

purchase, gift, devise, lease or sublease, and to accept jurisdiction over and to hold and own,

and dispose of by sale, lease or sublease, real or personal property, including but not limited to

a health facility, or any interest therein for its corporate purposes; provided, however, that no

health facility or other real property acquired or constructed by the corporation shall be sold,

leased or otherwise transferred by the corporation without public hearing by the corporation after

twenty days public notice and without the consent of the board of estimate of the city;”

<16-

HHC is also given the power under section 7385[8] to enter into leases with private entities:

[8] to provide health and medical services for the

public [by] ... lease with any person, firm or private

or public corporation or association through and in

the health facilities of the corporation ...

The plain meaning of the words chosen by the Legislature leaves no room for doubt:

HHC is directly authorized to carry out its mission of ensuring New Yorkers have access to high

”» [3

quality health care, by “leas[ing] or subleas[ing]” “a health facility.” Unconsol. Laws

§ 7385[6]. HHC is authorized to sublease its hospitals to any type of entity without limitation,

including a for profit corporation, as long as HHC determines that the lease will further HHC’s

purpose of making good quality health care available for those who need it. The statute nowhere

requires that HHC only enter into leases with certain classes of health care providers, for

example governmental or not-for-profit corporations. Instead, in authorizing HHC to enter into

leases for the provision of health services, the Legislature broadly authorized HHC to "lease with

any person, firm, or private or public corporation ...." Thus, the Legislature authorized HHC

to sublease its health facilities, such as Coney Island Hospital, to a private company, such as

PHS.

The words of the HHC Act are unambiguous. Indeed, even the lower Court agreed that

the plain meaning of the statutory language authorized HHC to sublease Coney Island Hospital

to PHS, although it rejected this outcome as "incongruous" (Co 636; Ca 860). This was error.

A Court lacks the authority to rewrite a statute when its terms are clear. See, e.g., Lad v.

Grayly, 83 N.Y.2d 537, 545-46 (1994) (If statutory language is unambiguous, courts must give

effect to the plain meaning of the statute); Matter of State v Ford Motor Co., 74 N.Y.2d 495,

500 (1989) (same).

7.

Instead of applying the statutory language, the lower Court held that HHC is powerless

to make the changes necessary to ensure continuity of medical services for the poor if those

changes include subleasing hospitals to a private company. The lower Court fundamentally

misconceived HHC’s responsibilities. HHC cannot simply let itself "drown in red ink" (Co 639;

Ca 863); it must exercise its powers to adapt to the times as necessary to ensure continued access

to health care, especially for the poor people who depend on HHC. Indeed, if the economics

of health care demand, HHC may close entire hospitals, see Unconsol. Laws §7387[4]; Bryan

v. Koch. 627 F.2d 612 (2d Cir. 1980), aff’g 492 F.Supp. 212 (S.D.N.Y.) (upholding Sodas

of Sydenham Hospital); Jackson v. HHC, 419 F. Supp. 809 (S.D.N.Y. 1976) (upholding closing

of Morrisania Hospital). As the Court explained in Jackson, HHC “must have the discretion to

determine in what manner its services are to be dispensed.”

HHC subleased Coney Island Hospital because it believed PHS would be able to keep the

hospital afloat and available for poor people in need of medical care. At the same time, HHC

put strict limits on how far the profit motive could go; the sublessee must provide charity care

for the poor and uninsured and continue all important medical services. Under the sublease, the

Coney Island Hospital patient population will benefit from the improvements private sector

operation will bring to the hospital, while continuing to receive medical care without regard to

ability to pay. This was a decision that was within HHC’s authority under the literal terms of

the law and in light of the purpose of the HHC Act.

In creating the New York City Heath and Hospitals Corporation as a public benefit

corporation, in place of a traditional ‘government agency, the Legislature intended that HHC

13-

would have the flexibility to change as the times demanded. The Legislature intended above all

that HHC should not be locked into any particular method of health care delivery:

A system permitting legal, financial and managerial

flexibility is required for the provision and delivery

of high quality, dignified and comprehensive care

and treatment for the ill and infirm, particularly to

those who can least afford such services.

Unconsolidated Laws § 7382. The Legislature was concerned that a rigid adherence to particular

forms of delivering health care would end up hurting patients: "A myriad of complex and often

deleterious constraints and restrictions place a harmful burden on the delivery of such dniinia

treatment." Unconsol. Laws § 7382. Therefore, it instructed HHC to be flexible in pursuit of

efficient methods of providing health care: "Procedures inherent in the administration of health

and medical services as heretofore established obstruct and impair efficient operation of health

and medical services." Id. Thus, by entering into the sublease of Coney Island Hospital, HHC

is doing precisely what the Legislature intended it should do: taking the steps necessary to

provide better health care for New Yorkers, particularly the most vulnerable.

HHC had ample basis for its decision that the sublease would be the best way of carrying

out its mission. Current economic realities leave no assurance that particular services will

continue to be offered at Coney Island Hospital. HHC does not have an unlimited budget to

provide service on demand at all its facilities. Rather, it must -- while honoring its commitment

to the indigent and effectuating its overall mission -- allocate its resources wisely. To that end,

HHC has adjusted staffing levels, shifted the availability of services from one facility to another,

modified hours of service and indeed, where appropriate, closed entire programs or facilities.

-19-

See, e.g., Brvan v. Koch, 627 F.2d 612 (2d Cir 1980); Jackson v. HHC, 419 F.Supp. 809

(S.D.N.Y..1976).

HHC approved the sublease of Coney Island Hospital ("CIH") after its health care

consultant projected that if the hospital remained in HHC’s hands, there would be increased

pressure to reduce the range and availability of services for the poor and uninsured. (Co 565-

66; Ca 556-57):

With a limited ability to upgrade and modernize the facility

through capital investments, CIH is likely to find its base of

insured patients eroding against the growing competition in the

marketplace -- particularly for Medicare and Medicaid patients...

Given the decline in revenues CIH expects to collect in the period

ending in the year 2000 under HHC management, some

combination of reductions in the range of services, or the capacity

to deliver services, or both would be likely to occur. Under these

circumstances maintaining the level of access for the indigent

uninsured population would be an ongoing challenge to HHC.

On the other hand, by entering into the sublease with PHS, HHC arranged a guarantee

that the uninsured seeking care at Coney Island Hospital would be able to obtain medical services

valued at up to 115% of HHC'’s current charity care costs at the hospital. The 115% figure will

be calculated net of a medical inflation factor, and net of third party reimbursements.

Independent consultants who analyzed the sublease for HHC projected that the sublease’s charity

care obligation would be ample to meet demand well into the foreseeable future, even assuming

a 21% increase in indigent uninsured patients. (Co 553; Ca 562). In addition, PHS will invest

a minimum of $25 million in the hospital’s physical plant and is obligated to maintain in-patient

and out-patient programs in all "core service" areas offered at CIH as of the day before the

-20-

closing on the sublease.® HHC retained important oversight powers both explicitly in the

sublease and under the law as landlord.

The benefits of the sublease are not limited to Coney Island Hospital; they extend to the

system as a whole. Because of the sublease, approximately $17 million in HHC borrowing

capacity will be freed to be used for capital needs at other HHC facilities. In addition, HHC

will benefit from PHS’ assumption of the hospital's operating costs (including malpractice

liability), which will free HHC funds to strengthen the rest of the system (Co 400; Ca 403).

Thus, by arranging the PHS sublease, HHC has guaranteed a level and amount of services for

the poor and uninsured that HHC on its own could never make.

In sum, the proposed sublease is an innovative instrument for assuring that HHC's

mission of providing health care services to the indigent will be fulfilled in the future. There

is no magic in government being in "the hospital business," in the words of the lower Court.

HHC properly decided that in this instance, government would not be better at the "business"

side of hospitals. HHC has taken advantage of the private sector to ensure that the poor people

who depend on Coney Island Hospital will receive high quality health care in the years to come.

That determination was well within the powers expressly granted HHC by the HHC Act and,

therefore, should not have been second guessed by the Court below.

8 The sublease permits PHS to change the medical services if there is a radical change in the

practice of medicine, such as a vaccine that eliminates a disease. It provides that disputes over

changes in core services should be submitted to an arbitrator (Co 399; Ca 402). The lower

Court was strangely troubled by the provision for arbitration (Co 638; Ca 862). It is the public

policy of this State to encourage the use of alternative dispute mechanisms, especially arbitration.

See, e.g., Matter of 166 Mamaroneck Ave. Corp. v. 151 East Post Road Corp., 78 N.Y.2d 88,

93 (1991).

-21-

POINT TWO

ULURP DOES NOT APPLY TO THE SUBLEASE OF CONEY

ISLAND HOSPITAL.

The New York City Charter entabiithes a lengthy review process that the City must

follow when it wants to make changes in certain categories of land use: the Uniform Land Use

Review Process ("ULURP"), Charter § 197-c. ULURP is inapplicable to the case at bar because

HHC’s sublease of Coney Island Hospital does not fall within the scope of the statute and

because the Legislature intended that HHC would act without being enmeshed in City red tape.

The sublease does not fall under ULURP because HHC’s lease is not City property

ULURP does not create a general law applicable to all changes in land use. Instead, it

is of limited scope and only applies to the instances defined in the statute’s first subsection.

Mauldin v. New York Citv Transit Authority, 64 A.D.2d 114, 117 (2d Dept. 1978): "[T]he

applicability of [Charter § 197-c] is necessarily limited to the 11 paragraphs of subdivision a

thereof."

The subdivision that the lower Court found relevant in the case at bar is only applicable

to the sale, lease or exchange of City property. The provision applies ULURP to:

Sale, lease (other than the lease of office space),

exchange or other disposition of the real property of

the city....

N.Y.C. Charter § 197-c [a](10). Thus, when a claim is made under this section of ULURP, the

first question must be whether the "real property of the City" has been sold, leased or

exchanged.

Coney Island Hospital was once the real property of the City. But when HHC was

created, the City split the property into two legal parts. The City retained ownership of the fee

_22-

and gave HHC a long term lease on the former City hospital (Co 135; Ca 119). Therefore,

today there. are two separate legally cognizable real property holdings at Coney Island Hospital.

One, the fee, is held by the City and the other, the leasehold, is held by HHC.

The sublease of Coney Island Hospital to PHS is a transfer of HHC’s property -- the

HHC leasehold -- to PHS. The sublease does not concern the City’s property at Coney Island

Hospital -- the fee. The fee will not be sold, leased, exchanged or affected in any way.

Therefore, by its own terms ULURP does not apply to the transaction.

The lower Court declared without explanation that the sublease of Coney Island Hospital

is a transfer of the City’s property (Co 634; Ca 858). If the Court had applied property law to

the transaction, it would not have confused the physical piece of land (i.e. the buildings and

grounds of Coney Island Hospital) with the estate in property law that is being subleased.

It is well settled that ULURP’s use of real property terms should be interpreted by

applying the law of real property. Indeed, this Court has regularly turned to traditional property

law to determine whether a type of property interest acquired or disposed of by the City is one

that is covered by ULURP. Compare Matter of Davis v. Dinkins, 206 A.D.2d 365, 366-67 (2d

Dept. 1994), lv. app. den. 85 N.Y.2d 804 (1995) (applying real property law to find traditionally

essential terms of a lease not present); with Matter of Dodgertown Homeowners Assoc. Inc.

v. City of New York, 96-11382, _ A.D.2d __ (2d Dept. 1997), mot. lv. app. pending (applying

real property law to find lease where parties agreed on "surrender of absolute possession and

control of property to another party for an agreed-upon rental "}.

A leasehold interest is real property in and of itself, alienable apart from the fee. See,

e.g., Rowe v. Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Co., Inc., 46 N.Y.2d 62, 69 (1978) (law disfavors

limits on right to sublease as restriction on alienation of property); Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea

Co.. Inc. v. State, 22 N.Y.2d 75, 84 (1968) (leasehold is subject to condemnation award apart

from the fee); Restatement, Second, Property (Landlord and Tenant) § 15.1 (tenant’s interest in

property is freely transferable). See generally Mann Theatres Corp. v. Mid-Island Shopping

Plaza, Co., 94 A.D.2d 466, 470 (2d Dept. 1983), aff'd for reasons stated below, 62 N.Y.2d 930

(1984) ("[I]n the absence of statute or an express restriction in a lease, a tenant has the

unrestricted right to ... sublet.").

The existence of lessees’ property interest in their leaseholds pervades commercial and

residential transactions in this State. Commercial tenants regularly exercise their right to sublet

their property, see generally Oppenheimer & Co. Inc. v. Oppenheim, 86 N.Y.2d 685 (1995)

(discussing plan to sublease 33rd floor of One New York Plaza), and residential tenants sublease

even rent regulated apartments. See Perlbinder v. New York City Conciliation and Appeals

Board, 67 N.Y.2d 697 (1986). The City certainly recognizes the existence of leaseholds as

property; it has negotiated subleases for office space with tenants. See generally Maidgold

Assoc. v. Citv of New York, 64 N.Y.2d 1124 (1985). Indeed, research has found no reported

case holding, as did the Court below, that a leasehold is the fee owner’s, not the tenant's,

property.’

® The HHC Act requires that the City approve the leasing transaction, an approval that may be

analogized to the right commonly reserved by a landlord to consent to a sublease. Such rights

of approval by the landlord do not change the fact that the tenant has a property interest,

separate from the fee, in the property. See generally Restatement Second, Property § 15.2

(lease may require landlord’s approval to sublet). The City’s approval of the sublease is

exercised by the Mayor, consistent with the provisions of New York City Charter § 384. See

Point Three, infra.

24-

As a matter of real property law, the sublease of Coney Island Hospital is a disposition

of HHC’s property. Therefore, Charter § 197-c [a] (10), which regulates only dispositions of

the "property of the City", is inapplicable to the transaction.

The HHC Act preempts application of ULURP to HHC properties

Even if the literal terms of ULURP were applicable to the sublease, however, it would

be inconsistent with the State law that created HHC to subject HHC leasing transactions to the

ULURP Shivers As the Court of Appeals has held, ULURP does not govern transactions within

the scope of Charter section 197-c [a], if an overriding state interest requires ignoring its

strictures. Matter of Waybro Corp. v. Board of Estimate, 67 N.Y.2d 349 (1986).

In Waybro, the City transferred its property to the Urban Development Corporation

("UDC") as part of the 42nd Street Redevelopment Project. The Court of Appeals found that

in creating UDC, the Legislature intended that UDC acquire property without complying with

local real property review laws. Thus, even though the City’s decision to transfer property to

UDC fell within the terms of ULURP and the 42nd Street Redevelopment Project indisputably

is an important land use project, the Court held that the City should not follow the ULURP

process before it disposed of its property. The Court found in the UDC Act a legislative

intention to override ULURP, which the Court characterized as an "impenetrable layer of red

tape." Id. at 350.

HHC is a State law entity and ULURP is a local law. Where compliance with local law

is inconsistent with State law, the State law must take precedence pursuant to Municipal Home

Rule Law § 10(5). That section expressly prohibits a locality from enacting "local laws which

impair the powers of any other public corporation,” such as HHC. See General Construction

25.

Law § § 65, 66 (A "public corporation” includes HHC as a "public benefit corporation"). And,

there can be no doubt that imposition of ULURP’s requirements would indeed "impair" HHC'’s

powers as granted by the HHC Act.

While the HHC Act could not directly address the question of whether HHC should be

subject to ULURP because ULURP did not exist when the Act was written, the Legislature did

have a great deal to say about its intention that HHC should be freed from the City laws and

regulations that had made it difficult for the Department of Hospitals to act decisively. The

Legislature stated in the Act’s Declaration of Purpose that it was creating HHC to free polis

from City laws and regulations, which the Legislature characterized as a "myriad of complex and

often deleterious constraints and restrictions [that] place a harmful burden on the delivery of . . .

care and treatment." Unconsol. Laws § 7382. The Legislature found that City procedures

"obstruct and impair efficient operation of health and medical resources." It created HHC as

a public benefit corporation of the State, rather than a City agency, so that HHC could be "a

system permitting legal, financial and managerial flexibility." Unconsolidated Laws § 7382.

It would be directly contrary to this clearly stated legislative intent to find that HHC, having

been granted the power to sublease its facilities, is nevertheless subject to the City’s complex and

time consuming land use review procedures.

Further, the Legislature displayed an intention to override local land use review processes

by creating a special abbreviated process for review of dispositions of HHC property. The HHC

Act creates a stripped down procedure compared to the lengthy ULURP process. Instead of a

process spanning months of public reviews and hearings by Community Boards, Borough

Presidents, the City Planning Commission and the City Council, the HHC Act provides that

-26-

certain dispositions (including the sublease in the case at bar) should be reviewed at one public

hearing and. then consented to by the "Board of Estimate." Unconsolidated Laws § 7385(6).%°

The City may not subject HHC decision making to more public hearings and a significantly

longer review process without State authorization.

POINT THREE

THE MAYOR IS THE SUCCESSOR TO THE BOARD OF

ESTIMATE’S ROLE IN APPROVING DISPOSITIONS OF

HHC PROPERTY UNDER THE HHC ACT.

The HHC Act requires that the "Board of Estimate" consent to HHC dispositions of real

property. Unconsol. Laws.§ 7385(6)."" The Board of Estimate was declared unconstitutional

in Morris v. Board of Estimate, 489 U.S. 688 (1989), but the State has not yet amended many

of its laws, including the HHC Act, to eliminate references to the Board of Estimate’s consent

power. However, all the parties agree, and the lower Court held, that the reference to the Board

of Estimate in the HHC Act should be interpreted to require that the City consent to HHC’s

dispositions of property (Co 628; Ca 852). See New York Public Interest Research Group v.

Dinkins, 83 N.Y.2d 377, 385 (1994) (statutory repeals by implication are "not favored in the

law"): Friends of Van Vorhees Park, Inc. v. City of New York, Sup. Ct., N.Y. Co., Index No.

10 The Mayor succeeded to this approval authority under the HHC Act. See Point Three, infra.

I The relevant portion of the law provides:

no health facility or other real property . . . shall be

sold, leased or otherwise transferred by the

corporation without public hearing by the

corporation after twenty days public notice and

without the consent of the board of estimate of the

city;

27.

=

134520/93 (Huff, J.), aff'd, 216 A.D.2d 259 (1st Dept. 1995) (upholding Mayor’s exercise of

approval power for disposition of park land that State law conferred on the Board of Estimate).

The City body that succeeded to the Board of Estimate’s role in consenting to HHC

property dispositions is the Mayor. It is inconsistent with both the Council’s role under New

York City Charter and the nature of the HHC Act to find that the City Council has assumed any

part of the Board of Estimate’s consent authority over HHC leases. The Charter explicitly

transferred general consent authority over real property transactions from the Board of Estimate

to the Mayor, not to the Mayor jointly with the Council. The Council has succeeded to a partion

of the Board of Estimate’s role in reviewing land use decision making, but only to the decision

making that falls under ULURP. The Charter allocates to the Mayor all decision making

concerning property that takes place outside of ULURP. Finally, the HHC Act was intended

to streamline HHC decision making, an intention that would be thwarted by requiring Mayoral

and Council consent to HHC real property dispositions when the HHC Act provides for City

consent by only one, not two, bodies or officers of City government.

In allocating the authority to consent to HHC real property transactions to the Board of

Estimate, the State Legislature followed the City Charter’s allocation to the Board of the

analogous authority to consent to the City’s own real property transactions. Charter § 384(a),

in effect at the time the HHC Act was adopted, provided:

Disposal of property of the city. a. No property of

the city may be sold, leased, exchanged or otherwise

disposed of except with the approval of the board of

estimate and as may be provided by law unless such

power is expressly vested by law in another agency.

(emphasis added).

228-

The Mayor has succeeded to this authority to consent to real property transactions. When

the Charter was revised in 1989 to eliminate the Board of Estimate, the office of Mayor was

substituted for the office of the Board of Estimate in Charter § 384(a):

Disposal of property of the city. a. No real property of

the city may be sold, leased, exchanged or otherwise

disposed of except with the approval of the mayor and as

may be provided by law unless such power is expressly

vested by law in another agency.

(emphasis added). Thus, in reviewing HHC leasing transactions, the Mayor would perform the

identical function he or she performs in regard to the disposition of City property.

The Mayor's exercise of the consent power under the HHC Act is consistent with the

Charter’s general guideline regarding changes required by elimination of the Board of Estimate.

The Charter provides that functions formerly allocated to the Board of Estimate under other laws

should be given to the officer or body that exercises the comparable power under the Charter

itself. Charter § 1152(e), adopted by the voters in 1989, provides that:

the powers and responsibilities of the board of estimate,

set forth in any state or local law, that are not otherwise

devolved by the terms of such law, upon another body,

agency or officer shall devolve upon the body, agency or

officer of the city charged with comparable and related

powers and responsibilities under this charter . . . .

Application of this devolution provision is straightforward in the case at bar. Since the

Legislature gave the consent authority to the Board of Estimate when the Board had that power

under Charter § 384(a), and since the Mayor has succeeded to the consent authority under the

revised Charter § 384(a), the consent authority in HHC Act § 7385(6) devolves upon the Mayor.

See Tribeca Community Assoc.. Inc. v. UDC, Sup. Ct,. N.Y. Co., Index No. 29355/92

(Lippman, J.) at page 31 (" [T]he City Council does not have authority to approve the terms and

£20.

conditions of sales, leases or other dispositions . . . ."), aff'd, 200 A.D.2d 536 (1st Dept. 1994),

lv. app. den. 84 N.Y.2d 805 (1994).

The lower Court nevertheless held that the Council has the authority to review the Coney

Island Hospital sublease because HHC lease transactions are subject to land use review under

ULURP. This was mistaken because ULURP does not apply to the sublease of HHC’s Coney

Island Hospital lease and the Legislature never intended to subject HHC to complex City land

use review laws. See Point Two, supra. Indeed, the Legislature could not have intended that

the Board of Estimate’s consent power under the HHC Act be the same power as the Board of

Estimate’s land use review power under ULURP because ULURP did not even exist when the

HHC Act was adopted.

After ULURP became part of the City Charter in 1977, the Board of Estimate exercised

its HHC Act consent authority and deemed that authority to be separate and apart from its

ULURP decision making. In 1985 HHC subleased a portion of Bellevue Hospital to Enzo

Biochem, Inc., a biotechnology firm. In order to allow Enzo Biochem to run a manufacturing

business on the site two Board of Estimate actions were necessary: first, the area had to be

rezoned; second, the Board had to consent to the HHC sublease of the property to Enzo

Biochem. The rezoning involved a change by the City in its zoning text and was for that reason

subject to ULURP (Co 360-63; Ca 357-60). The Board of Estimate approved the rezoning,

exercising its ULURP powers.'”? Months later, the Board approved the terms of the HHC

12. The Board of Estimate resolution regarding the zoning change stated (Co 372; Ca 369):

"Resolved, By the Board of Estimate, pursuant to the provisions of Section 200 of the New York

City Charter, that the resolution of the City Planning Commission . .. reading as follows:

(continued...)

=30-

a

sublease. Significantly, the Board specifically noted that in granting consent to the HHC

sublease it was acting under the HHC Act, not pursuant to the Board's ULURP authority under

former section 197-c(-) to approve the land use impacts of property dispositions.” Indeed, the

ULURP process -- which included review by community boards and the City Planning

Commission -- addition to the Board of Estimate, was not followed in connection with the

approval of the lease to Enzo Biochem.

- The Council has succeeded to those land use powers the Board of Estimate exercised

under ULURP, but ULURP is not a general grant of authority over all real rok

transactions. There are land use powers that fall outside of ULURP, as this Court has

recognized in holding that ULURP applies only to the specific transactions listed in section 197-

cla]. See Davis v. Dinkins, supra, 206 A.D.2d at 368; Mauldin v. New York City Transit

12 2 (...continued)

Resolved, By the City Planning Commission, pursuant to Section 197-c and 200

of the New York City Charter that the Zoning Resolution of the City of New

York, . . . is further amended . . . by establishing within an existing R8 District,

a C2-5 District. . . .

be and hereby is approved.

13 The Board of Estimate resolution approving the HHC sublease stated (Co 310; Ca 342):

“Resolved, that the Board of Estimate, pursuant to McKin. Unconsolidated Laws, Section

7385.6 concurs in the determination [by HHC] to enter into a lease agreement with Enzo

Biochem... 2."

Plaintiffs argued below that the Board of Estimate heard testimony regarding potential land use

impacts of the Enzo Biochem transaction while it debated the exercise of its HHC Act consent

authority (Co 323-34; Ca 710-826). The Board could have considered such matters pursuant to

its Charter § 384(a) consent authority or pursuant to its non-ULURP authority over land use

matters in general. The Board's ultimate approval of the sublease, however, was expressly

based on the HHC Act and not on ULURP.

31-

Authority, supra, 64 A.D.2d at 114. The Charter gave the Council no source of land use review

authority other than the powers given in ULURP. Instead, the Charter specifically provides that

the Council may only exercise its land use powers by following the process laid out in ULURP

itself. See Charter §§ 28[a]; 384[b][5].

The general power to exercise judgment and discretion with respect to real property

outside the scope of ULURP resides in the Mayor. The Charter provides that all residual, i.e.

unallocated, powers of the City reside in the Mayor: "The Mayor, subject to this charter, shall

exercise all the powers vested in the City, except as otherwise provided by law." hi § 8.

Accordingly, the Mayor is not only the proper successor to the Board of Estimate under the

HHC Act by virtue of the powers he possesses under Charter § 384(b), but to the extent that

exercise of "consent" under HHC Act might implicate land use concerns that fall outside the

scope of ULURP, the Mayor is also the appropriate successor to the Board by reasons of

Charter § 8.

Moreover, the sublease of Coney Island Hospital does not raise land use concerns; the

use of the site as a hospital will not change. Plaintiffs’ objections to the sublease have nothing

to do with land use; rather their arguments concern whether HHC should privatize, whether PHS

will do a good job in running Coney Island Hospital and whether the poor and uninsured will

be harmed by the sublease. These are important questions regarding health care policy. They

do not concern land use planning.

Recognizing this, plaintiffs did not cite only the Council's land use powers under ULURP

to the Court below. Instead, they argued that Council approval should be read into the HHC

Act in order to balance the Mayor’s authority over HHC decision making. The City Council

32.

has made the same argument to the Legislature over the years by proposing several bills to

amend the HHC Act to give it greater authority over HHC, including the authority to consent

to HHC real property dispositions under the HHC Act. The State Legislature has not seen fit

to act upon those proposals.’ Having failed to convince the State lawmakers to rewrite the

HHC Act, plaintiffs now seek to amend the statute through this litigation instead.

‘The State Legislature gave the Mayor the responsibility to take the lead in setting hospital

health care policy. The HHC Act recognizes the primacy of the Mayor in the oversight of

HHC, by, among other things, requiring HHC to "deliver health and medical service 5 the

public in accordance with policies and plans" of Mayoral appointees'> -- not those of the Board

of Estimate or City Council which, after all, existed at the time of the Act’s adoption.

14 A 11048 was introduced on behalf of the Council in June 1996 and A. 8396 was introduced

in February 1996. Relevant parts of the bills and memorandum in support are in the Record at

(Co 312-21; Ca 344-55). Similarly, the Mayor and the Council at one time engaged in

negotiations over the terms of a bill that would reallocate the powers referred to the Board of

Estimate under a number of State laws. As part of the negotiations, the Mayor agreed to a

proposed bill giving the Council a role in approving HHC property transactions under the HHC

Act. The negotiations collapsed and the Legislature never enacted the proposed bill into law (Co

326,.362; Ca 359). :

15 Unconsol.Laws § 7386(7) provides that HHC

shall exercise its powers to provide and deliver

health and medical services to the public in

accordance with policies and plans of the

administration with respect to the provision and

delivery of such services . . . .

The term "administration" as defined, in section 7383(2), is "the health services administration

of the city of New York." The agency was abolished by Local Law No. 25 of 1977, which

established the Department of Health and the Department of Mental Health, Mental Retardation

and Alcoholism Services to exercise its functions. Each of those agencies is headed by a

commissioner appointed by the Mayor.

The State Legislature did expressly give the Council a role in HHC policy making. The

Council must designate five of the fifteen Mayoral appointees to the HHC Board. Unconsol.

Laws § 7384(1)." The lower Court erred in second guessing the Legislature to find that the

Council should have additional powers in overseeing HHC because it has land use powers under

ULURP.

The sublease of Coney Island Hospital to PHS has been the subject of extensive

discussion, review and public hearings, as required by law. The sublease has been debated by

members of the public at public hearing, pursuant to Unconsol. Laws § 7385[6] and the Neb

York City Charter § 556(m). It has been studied by the HHC Board pursuant to the State

Environmental Quality Review Act. The members of the HHC Board of Directors exercised

their responsibilities under the HHC Act by thoroughly exploring the medical, financial, and

legal issues related to PHS in a series of public sessions. The Mayor too will review the

sublease and make an independent determination pursuant to Unconsol. Laws § 7385][6]

regarding whether to approve its terms. Finally, pursuant to Public Health Law § § 2801, 2805,

the State Department of Health and the Public Health Council will perform an independent

analysis of the application by PHS for permission to manage Coney Island Hospital.

In sum, State law provides that a serious decision such as the sublease of Coney Island

Hospital be thoroughly aired before the public and studied by many governmental agencies. But

not every body of government has jurisdiction over every action taken by government. The

16 The HHC Act provides that the Council designates and the Mayor appoints five Board

members, the Mayor designates and appoints five Board members, five Board members are ex

officio City officials, and the Chief Executive Officer is chosen by the fifteen other Board

members. Unconsol. Laws § 7384 [1].

“34

State has granted the Council no authority to review an HHC determination to sublease one of

its hospitals, beyond the Council’s role in designating a number of members of the HHC Board.

The lower Court erred in expanding the Council’s role beyond that provided by State law.

Dated:

CONCLUSION

THE ORDER AND JUDGMENT APPEALED FROM SHOULD

BE REVERSED AND SUMMARY JUDGMENT SHOULD BE

GRANTED DEFENDANTS.

New York, New York

March 10, 1997

PAUL A. CROTTY

Corporation Counsel of the City d New Yak

Attorney for Defendants

100 Church Street

New York, New York 10007

(212) 788-1024

JEFFREY D. FRIEDLANDER,

DAVID KARNOVSKY,

DANIEL TURBOW,

ELIZABETH DVORKIN,

of Counsel

-35-