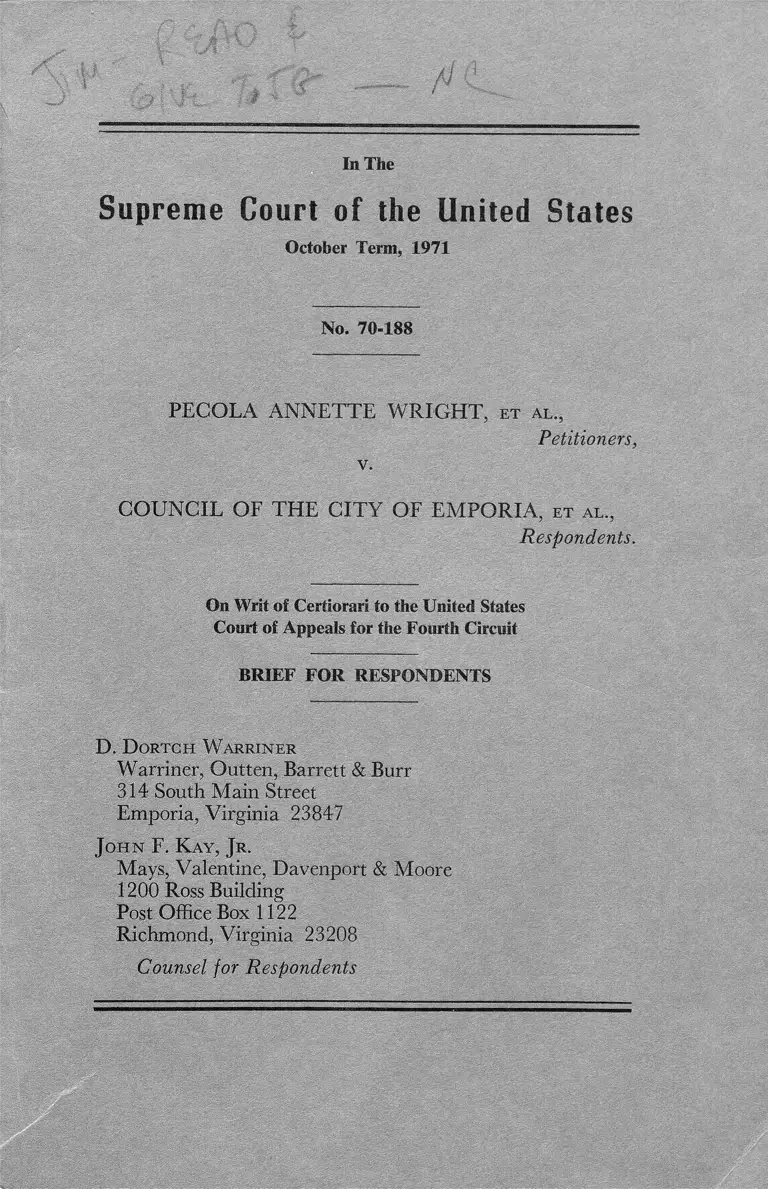

Wright v. Council of the City of Emporia Brief for Respondents

Public Court Documents

October 4, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wright v. Council of the City of Emporia Brief for Respondents, 1971. 078b0e91-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5446ed1e-3f33-4f04-aa0a-cf89aae62065/wright-v-council-of-the-city-of-emporia-brief-for-respondents. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1971

No. 70-188

PECOLA ANNETTE W RIGHT, e t al .

Petitioners,

v.

COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF EMPORIA, e t a l .

Respondents,

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

D . D o rtch W a rriner

Warriner, Outten, Barrett & Burr

314 South Main Street

Emporia, Virginia 23847

J o h n F. K ay, J r .

Mays, Valentine, Davenport & Moore

1200 Ross Building

Post Office Box 1122

Richmond, Virginia 23208

Counsel for Respondents

Question Presented .......................................................................... 1

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions I nvolved............... 2

Statement ...................................................................... 3

Transition of Emporia from Town to C ity .................................. 3

The Contract with Greensville County.......................................... 4

Emporia’s Decision to Operate Own School System ................. 5

Quality of Unitary System to be Operated by Emporia Superior

to That of County...................................................................... 10

Decision of the District C o u rt.......................................... 16

(a) Proposed System ............................................................... 16

(b) Reasons for Emporia’s Decision .................................... 17

(c) Effect on County ............... ....................... ....................... 18

Decision of Court of Appeals............................................. 20

Summary of Argument .................................................................... 21

Argument

I. The Law Of Virginia Vests The Power And The Duty

Upon The City Of Emporia To Operate And Maintain A

Public School System................................................ 23

A. Counties and Cities of Virginia Are Independent of

Each Other ........................................................................ 23

B. Emporia Became A City Pursuant to Long Existing

State Law ........... 24

C. Cities in Virginia Have the Right and Duty to Operate

and Maintain Own School Systems.................................. 25

II. Operation By The City Of Its Own School System Would

Violate No Constitutional Rights Of Petitioners .................. 28

A. Petitioners’ Rights ............................................................ 28

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

i

B. Proposed Action of the C ity .............................................. 32

C. Petitioners’ Rights Will Not Be Violated By the Pro

posed Action of the C ity .................................................... 33

D. Proposed Action of City Meets Any Constitutional Test

to Which It May Be Fairly Subjected............................. 43

C o n c l u sio n .................................................................... ...................................... 50

Br ief A ppe n d ix ...............................................................................................A pp. 1

Page

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S. 19, 24 L.Ed.2d

19 (1969) .............................................................................29, 30, 45

Aytch v. Mitchell, 320 F. Supp. 1372 (E.D. Ark. 1971) ................ 39

Bowman v. County School Board of New Kent County, 391 U.S.

430 (1968) ......................................................................................... 4

Brown v. Board of Eduation, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) (Brown I) ..29, 41

Brown v. Board of Educ., 349 U.S. 294 (1955) (Brown II) ....... 49

Burleson v. County Bd. of Election Com’rs., 308 F. Supp. 352

(E.D. Ark. 1970) ......... 39

City of Richmond v. County Bd., 199 Va. 679 (1958) .................... 23

Colonial Heights v. Chesterfield, 196 Va. 155 (1954) ................... 24

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ................................................ 31

Deal v. Cincinnati Board of Educ., 369 F.2d 55 (6th Cir. 1966),

cert, denied, 389 U.S. 847 (1967) ................................................ 41

Classman Construction Company v. United States, 421 F.2d 212

(4th Cir. 1970) ...................... 36

ii

Green v. School Bd. of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968)

4, 29, 30, 31, 46, 49

Haney v. County Bd. of Educ., 410 F.2d 920 (8th Cir. 1969) ....... 40

Jenkins v. Township of Morris School Dist., ..... A.2d ..... (N.J.

1971) ................................................................................................. 39

Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., No. 30154 (5th Cir., June 29,

1971) ................................................................................................. 37

Murray v. Roanoke, 192 Va. 321 (1951) .......................................... 23

Palmer v. Thompson, 403 U.S. 217, 29 L.Ed.2d 438 (1971) ....... 49

School Board v. School Board, 197 Va. 845 (1956) ........................ 26

Spencer v. Kugler, 326 F. Supp. 1235 (D.C.N.J. 1971) ................ 40

Stout v. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ., 448 F.2d 403 (5th Cir.

1971) ................................................................................................. 38

Supervisors v. Saltville Land Co., 99 Va. 640 (1901) ................. 24

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402 U.S. 1

(1971) ..................................29, 30, 31, 34, 37, 38, 41, 45, 48, 50

United States v. Scotland Neck City Board of Education, 442

F.2d 575 (4th Cir. 1971) ................................................ ....21, 23, 48

Page

Constitution

Constitution of United States:

Fourteenth Amendment ............................................................22, 28

Constitution of Virginia:

Article V III, § 5 .............................................................................. 2

Article V III, § 7 .............................................................................. 2

Section 133 .................................................................................. 2, 25

Codes

Code of Virginia, 1950, as amended:

Title 15.1, ch. 22 24

§ 15.1-982 .................................................. ...................................... 2, 3

§ 15.1-987 through 15.1-1010 ........................................................ 2

§ 15.1-1005 ........................ 24

§ 22-30 .................... 2

§ 22-34 ......... 3

§ 22-43 ............................................................................................... 2

§ 22-93 ............ .............................................................................. 2, 26

§ 22-97 ......................................... ......................................... ........2, 26

§ 22-100.1 ..... ...................... ............................................................. 2

§ 22-100.2 ............................................................................. ............ 3

§ 22-100.3 ............................... 2

Code of Virginia, 1919:

§ 786 ................................................................................................ 26

Acts

Acts of Virginia:

Acts of Assembly, 1891-1892, ch. 595 ............................................ 24

Other Authorities

G. Adrian, State and Local Governments, 249 (2d ed. 1967) ....... 38

C. Bain, “A Body Incorporate”—The Evolution of City-County

Separation in Virginia, ix, 23, 27, 35 (1967) ............................ 38

Developments in the Law—Equal Protection, 82 Harv, L. Rev.

1065 (1969) .............................................................................. ..45, 49

Page

iv

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1971

No. 70-188

PECOLA ANNETTE W RIGHT, e t a l„

Petitioners,

v.

COUNCIL OF THE CITY OF EMPORIA, e t a l .,

Respondents.

On Writ of Certiorari to the United States

Conrt of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENTS

QUESTION PRESENTED

Respondents believe that the question presented is:

Was the Court of Appeals correct in deciding that the

constitutionally protected rights of petitioners would not

be violated if the City of Emporia, an independent

political subdivision of the Commonwealth of Virginia,

operates a unitary school system separate from that of

the County of Greensville.

Petitioners’ statement of the question presented (PB 2 1)

1 The following designations will be used in this brief:

PB—Petitioners’ brief

RA—Appendix to this brief of respondents

SA—Appendix to petitioners’ supplemental brief in support of

petition for writ of certiorari

2

is misleading, inaccurate and not clear. It is misleading in

that it ignores that the City of Emporia is an independent

political subdivision for all governmental purposes—it is not

just a school district.

It is inaccurate in stating that “the changed boundaries

result in less desegregation” for two reasons. First, no boun

daries have been changed, as such—rather, a “town” be

came a “city” under long-standing state transition statutes

and no boundaries were changed. Second, operation of a

separate school system by the City would not result in “less

desegregation” in either the County or the City.

It is not clear what petitioners mean in stating that “for

merly the absence of such boundaries was instrumental in

promotion segregation.”

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

1. Va. Const. Art. IX, § 133, which was in effect until

July 1, 1971, is set forth at RA 1, and Va. Const., Art.

V III, § 5(a) and § 7, which became effective July 1, 1971,

are set forth at RA 2.

2. Va. Code Ann. §§ 15.1-978 through 15.1-1010 (1950),

which relate to the transition of towns to cities in the Com

monwealth of Virginia. Va. Code Ann. § 15.1-982 (1950),

as in effect on July 31, 1967, is set forth in part at RA 2.

3. Va. Code Ann. § 22-93, is set forth at RA 3 and

§ 22-97, is set forth at RA 3, et seq.

4. The following sections of the Virginia Code, which are

set forth in the appendix to petitioners’ brief, were amended,

effective July 1, 1971, and are set forth, as amended at RA

2, 3, 7 respectively: §§ 22-30, 22-43, 22-100.1 and 22-100.3.

3

5. Va. Code Ann. §§ 22-34 and 22-100.2, set forth in the

appendix to petitioners’ brief, were repealed effective July 1,

1971.

STATEMENT

Transition of Emporia from Town to City

On September 1, 1969, Greensville County had a public

school population of 2,616 children of whom 728 were white

and 1,888 were Negro. On the same date, the City of Em

poria had a public school population of 1,123 of whom 543

were white and 580 were Negro (304a) ,2 Four school build

ings—three elementary and one high—are physically lo

cated in Greensville County. Three school buildings—two

elementary and one high—are physically located in the City

(294a).

Prior to July 31, 1967, Emporia was an incorporated town

and, as such, was a part of Greensville County, Virginia. On

July 31, 1967, the Town of Emporia became an independent

city of the second class pursuant to the provisions of the Code

of Virginia.3 The evidence is uncontradicted that the moti

vating factor behind the transition was the desire of Em

poria’s elected officials to have Emporia receive the benefits

of the state sales tax that had been recently enacted and to

eliminate other economic inequities (123a, 124a). There has

been no charge by petitioners that the decision to become a

city was in any way motivated by the school desegregation

situation. There has been no finding by the District Court to

impugn the motives or purposes of the City in effecting this

transition.

The Court of Appeals pointed out:

2 References are to the Single Appendix filed herein.

3 Va. Code Ann. § 15.1-982 (RA 2)

4

At the time city status was attained Greensville

County was operating public schools under a freedom

of choice plan approved by the district court, and

Green v. County School Board of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968), invalidating freedom of choice

unless it “worked,” could not have been anticipated by

Emporia, and indeed, was not envisioned by this court.

Bowman v. County School Board of Charles City Coun

ty, 382 F. 2d 326 (4th Cir. 1967). The record does not

suggest that Emporia chose to become a city in order

to prevent or diminish integration. Instead, the motiva

tion appears to have been an unfair allocation of tax

revenues by county officials (314a).

The Contract With Greensville County

On April 10, 1968, the City and County entered into an

agreement pursuant to which the County was to provide

specified services, including schools, for the people of Em

poria for a period of four years (32a). It provided for earlier

termination under certain circumstances. As evidenced by

minutes of the County Board of Supervisors, this contract

was entered into by the City under the threat of expulsion

by the County of the City children from the County schools

at mid-term (31a). The District Court stated:

Only when served with an “ultimatum” in March of

1968, to the effect that city students would be denied

access to county schools unless the city and county came

to some agreement, was the contract of April 10, 1968,

entered into (305a).

Further, the contract was entered into only after the City

School Board had fully explored the feasibility of operating

its own system immediately upon transition and after negoti

ations toward establishing a joint school system with the

County had failed (227a, et seq.). As found by the District

Court:

5

Ever since Emporia became a city, consideration has

been given to the establishment of a separate city system

(305a).

The City School Board determined that for practical rea

sons it was impossible to establish its own system at that time

(227a).

The District Court also found that the City’s second choice

“was some form of joint operating arrangement with the

county, but this the county would not assent to” (305a). The

minutes of the County Board of Supervisors make this clear

(30a).

Petitioners state that instead of filing suit against the

County to establish the City’s equity in the school property

in 1967, the City “negotiated for preferred contractual terms

(see 230a)” (PB 5). It is obvious that had the City chosen

to file suit at that time the County would have refused to

permit City students to attend the County schools during the

pendency of that suit. Therefore, as a practical matter, that

choice was not available to the City. Further, the record is

clear that “preferred contractual terms” were not obtained

by the City—on the contrary, the County’s terms were forced

upon the City (230a-233a).

The contract of April 10, 1968 terminated after the 1970-

71 school year as the District Court recognized it would

(296a). Were it not for this proceeding, the City of Emporia

would be free to operate its own system during the current

school year. Actually, it would be obligated so to do under

the law of the Commonwealth of Virginia.

Emporia’s Decision to Operate Own School System

During the 1968-69 school year, the County operated

under a freedom-of-choice plan which had been approved

by the District Court. On June 25, 1969, the District Court

6

enjoined the County to disestablish the existing dual school

system and to replace it with a racially unitary system. Sub

sequently, a plan was approved which required the assign

ment of all pupils in the system as follows (295a) :

School Grades

Greensville County High

Junior High (Wyatt)

Zion Elementary

Belfield Elementary

Moton Elementary (now Hicksford)

Emporia Elementary

Greensville County Training

10, 11, 12

8, 9

7

5, 6

4 ,5

1 ,2 ,3

Special Education

Under this plan, an Emporia child who begins in the

first grade of the Greensville system is required to attend six

different schools—possibly seven—during the course of his

elementary and secondary education. In grades 1-3 and in

grades 10-12, he would attend schools located in the City;

in the remaining grades, he would be required to go outside

the City of his residence to attend schools located in the

County.

After the order of June 25, 1969 was entered by the Dis

trict Court, the bi-racial (125a) City School Board de

termined to operate its own schools for 1969-70. It planned

a racially unitary system in which all elementary school chil

dren—black and white—would be assigned to one school and

all high school children—black and white—would be as

signed to another school (129a). The City system would

have been approximately 52% black and 48% white. The

County system would then have been approximately 72%’

black and 28% white. The combined system is approxi

mately 66% black and 34% white (304a, 316a).

Petitioners repeatedly refer to the fact that it was the

“desegregation” decree of June 25, 1969 that caused the

7

City to decide to operate its own system (e.g. PB 8, 9, 11,

13). They argue that the separate system “was conceived in

response to, and represents a determined effort to evade, the

desegregation decree of the district court” (PB 48); that the

timing of the city’s decision “strongly suggests racial motiva

tion” (PB 52); and that “the claims of the city to a continu

ing and long-standing desire to free itself from county domi

nation which prevented attainment of educational quality,

are far outweighed by its unexplained failure to take any

action until integration was to occur, [and] its awareness

that a separate system would contain a more palatable racial

mix which might prevent white flight * * *” (PB 54).4

Throughout their brief, petitioners attempt to convey

the impression that the City was satisfied with the system

being operated by the County until the “pairing plan” re

quired by the Order of June 25, 1969 was put into effect

(e.g. PB 5, 13). The record is clear that while the City wras

satisfied with the assignment plan in effect prior to that

order (freedom of choice), it was not satisfied with the con

4 Petitioners state on pages 8 and 9 of their brief that the City offered

to accept county students into the city system on a tuition basis. They

neglect to state that the City included in the assignment plan it sub

mitted to the Court in December 1969 a provision that no students

would be accepted from outside the City until approval was obtained

from the District Court (224a, 225a). This action was taken after the

hearing on the preliminary injunction in August 1969 when the Dis

trict Court expressed some concern about the City’s plan to accept in

its system students residing in the County on a tuition, no transporta

tion basis. While the City intended to accept such students on a “first

come, first served” basis without regard to race, it recognized that this

plan had apparently cast doubt upon the good faith intention of the

City to operate a unitary system composed of approximately an equal

number of white and Negro students. Therefore, while it believed such

doubt to be unjustified, it decided to affirmatively incorporate in its

plan that it would accept no students from another school district

without first obtaining approval of the District Court (225a). The

District Court so found (296a).

8

tractual arrangement under which it had no control over

the system nor was it satisfied with the system itself.5

The District Court accurately stated Emporia’s principal

reason for its decision to operate its own system to be:

Emporia’s position, reduced to its utmost simplic

ity, was to the effect that the city leaders had come to

the conclusion that the county officials, and in particular

the board of supervisors, lacked the inclination to make

the court-ordered unitary plan work. The city’s evidence

was to the effect that increased transportation expendi

tures would have to be made under the existing plan,

and other additional costs would have to be incurred in

order to_ preserve quality in the unitary system. The

city’s evidence, uncontradicted, was to the effect that

the board of supervisors, in their opinion, would not be

willing to provide the necessary funds (305a, 306a).

The testimony of the Chairman of the City School Board

with respect to the reasons for which the City decided to

operate its own schools is found on pages 236a through 242a

of the appendix. In summary, the reasons behind the de

cision were that, in the opinion of the City, the County was

not able to operate a unitary school system successfully, that

the County would not be willing to expend the necessary

funds to make a success of a unitary school system, that the

City was willing to do so, that a successful public school

system was a necessary part of the future well being of the

In support of their claim that the City was satisfied with the

County system, petitioners refer the Court to pages 163a and 235a.

At page 163a, Mr. Lee, the mayor of the City testified:

“We have never been happy with the system. . . .”

At page 235a, Mr. Lankford, chairman of the City School Board

testified that he thought the County had operated a reasonably effec

tive system but that the City did not plan to renew the contract.

At page 147a, Mr. Lankford testified:

I personally, and I think my School Board since we were formed

two years ago, have never been happy [with the County system].”

9

community, and that Emporia must control its own system

in order to accomplish these ends.6

Additionally, that the frequent transfers from building to

building required under the plan was a source of primary

concern is illustrated by the following colloquy between the

District Judge and the Chairman of the City School Board:

The Court: What you are really saying, Mr. Lank

ford, everybody has been at you, the Council (sic) and

myself and I don’t mean to, but I want to get it straight.

What you are really saying is that the reason that pre

cipitated this, and the primary reason, is the fact that

your children and all the children have got to transfer

schools more frequently than they have in the past and

you consider that to be bad?

The Witness: I consider that to be bad, yes, sir, and

the—

The Court: I am certainly in accord with you that it

is not the best thing, but that is really the reason, is it

not?

The Witness: That is the basic reason that we wish

to operate our city school (152a, 153a).

The Mayor of the City testified that the order of the Dis

trict Court did cause the City “to try and act with haste”

(121a). However, the concern of the City was that its chil

dren would attend six different schools from the first grade

through high school, that the City was paying more than its

6 At the time of the hearings in the District Court on August 8, 1969

and December 18, 1969, the contract of April 10, 1968 was in effect.

The evidence was that the County completely controlled the operation

of that system and that the City had no control over the school budget,

over the selection of the school board, over the curriculum, over the

hiring of teachers, over the salaries to be paid to teachers, or over any

other matter relating to the operation of the schools (158a, 159a,

242a). At the present time, the contract now having terminated, the

situation is the same.

10

fair share of the cost of the County School System which cost

would be increased by the increased transportation required,

that such money could be applied to provide a better school

program for city children—black and white—if all its ele

mentary students were educated in one school and all its high

school children were educated in another school (121a

122a). V

_ Therefore, it is true—and freely conceded—that the as

signment plan which was ordered by the District Court on

June 25, 1969 precipitated the decision of the City to accel

erate the time it would operate its own system. However, it is

equally true—and here emphasized—that it was not the

integration aspects of the plan that precipitated the decision.7

Quality of Unitary System to be Operated by Emporia

Superior to that of County

On August 1, 1969, the petitioners filed a supplemental

complaint in, and added the School Board and Council of

the City of Emporia as parties defendant to, the action pend

ing in the District Court. Until that time, the action was an

“ordinary” desegregation suit to which the County school

authorities were the only parties defendant. By the supple

mental complaint petitioners sought to enjoin the City from

operating its own school system and on August 8, 1969 the

7 The Chairman of the City School Board testified:

Q. Now, at the present time I believe you testified that the

ratio is approximately 60-40 in the county? A. Yes, sir to my

knowledge that is about right. 5 1

Q. And if the city formed the city school system your testi

mony is it would be approximately 50-50? A. Approximately.

Q. In the city? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Is this a matter of great moment to the City of Emporia?

A. No, sir.

Q. Is that the motivating influence of the City of [Emporial

A. No, sir (152a). r

11

District Court entered an order temporarily enjoining the

City from so doing (195a). The City decided not to appeal

the order granting the temporary injunction but rather to

follow the course of presenting the City’s case in an orderly

manner to the District Court at a hearing on whether the

injunction should be made permanent (186a, 187a). The

earliest date that the District Court could assign for such a

hearing was December 18, 1969 (188a).

The City then proceeded to prepare itself to be in a

position to put its system in effect just as soon as it was per

mitted to do so. It employed Dr. H. I. Willett, who had been

superintendent of the Richmond, Virginia, public school sys

tem for 22 years and who was then associated with Virginia

Commonwealth University, to design a budget specially

tailored to meet the needs and problems of the unitary sys

tem which Emporia proposed to operate (252a, 259a, 261a,

262a) ,8 Dr. Willett’s budget, which was adopted by the City

School Board and the City Council (200a, 287a) , is included

in the Appendix beginning at page 202a. The budget mes

sage is particularly significant (206a-215a).

The City also employed Dr. Neil H. Tracey, Professor of

Education at the University of North Carolina,9 to evaluate

the present system as it was being operated by the County of

Greensville, to compare it with the system proposed by the

8 On at least two occasions in their brief (PB 19, 50), petitioners

refer to the fact that the proposed budget was not prepared until after

the temporary injunction had been entered “and the City had gained

a better idea what evidence might best serve its cause” (PB 50).

Obviously, a budget would not have been prepared by the City prior

to its decision to operate its own system and that decision was not

made until a short time before the temporary injunction was entered.

9 Dr. Tracey was erroneously referred to in the opinion of the Dis-

strict Court as being from Columbia University and in the transcript

of the proceedings of December 18, 1969 (266a, et seq.) as being from

the University of New York.

12

City of Emporia, and to testify at the hearing on whether

the injunction against the City should be made permanent.10

At that hearing on December 18, 1969, Dr. Tracey testified

that the assignment plan ordered by the District Court for

Greensville County has an adverse effect from, an educational

standpoint (272a-274a). In summary, Dr. Tracey’s conclu

sions were based on the following factors:

1. Funds which could otherwise be applied to educational

purposes must be applied to the expenses of providing trans

portation (274a).

2. Time that is required to transport the pupils serves no

useful educational purpose (274a).

3. Educational resources including teachers, text materials,

library materials and other instructional materials must be

divided among the buildings in which the various grades are

taught. With respect to the elementary grades, this results

in curtailing the resources available to the pupils housed in

each building. Since most children have an achievement

range of about double the number of years of their grade

designation, the curtailment of the educational resources re

sults in the curtailment of the range of instructional and in

10 On page 19 of their brief, petitioners state that Dr. Tracey “testi

fied that it was his ‘understanding’ that he was not serving the City in

‘any attempt to resegregate or to avoid desegregation’ (269a).” Dr.

Tracey’s testimony on this point was: [questions by Mr. Kay].

Q. Now, sir, at the time that you were approached to accept

this assignment, did you place any conditions on your acceptance?

And if so, what were they? A. Yes, I placed this basic condi

tion on acceptance of any such assignment, that the intent of the

people involved, the Emporia people in this instance, should be

specifically not related to any attempt to resegregate or to avoid

desegregation or to avoid integration.

Q. And, if you had ascertained that this was the intent, what

was your understanding with the City? A. My understanding

was that I would riot serve in this capacity, at all (269a).

13

dependent educational opportunities available to the pupils

(272a, 273a).

Furthermore, Dr. Tracey testified that the effect of his

toric segregation of the races is not eliminated purely by a

proportionate mixing of the races. In his opinion, special

educational opportunities must be afforded to solve these

problems (269, 270a). Dr. Tracey testified that an exami

nation of the Greensville County System indicated that the

extra effort required to provide these opportunities was not

being made (271a, 272a, 274a). On the other hand, an

examination of the system proposed by Dr. Willett, which

had been adopted to the extent possible by the City, indi

cated that it would make the necessary effort (275 a, et seq.).

In this connection, Dr. Tracey studied the budget message

and budget (275a) prepared for the City School Board by

Dr. H. I. Willett.

Petitioners state that Dr. Tracey compared the educa

tional programs of the County with those proposed by the

City “without reference to the racial composition of the two

systems” (PB 19). In support of that statement, they quote

fragments of answers of Dr. Tracey to two different questions

(PB 20). Neither the questions nor the answers cited by

petitioners support the conclusion that Dr. Tracey’s compari

sons were made “without reference to the racial composition”

of the systems (269a, 270a). Dr. Tracey’s entire testimony

was directed to the point that special educational effort must

be exerted to eliminate the effects of segregation (270a)11

11 On direct examination, Dr. Tracey testified:

Q. Is a special effort required by locality and school officials

to provide such a system, in your opinion?

A. Yes, special effort. There are two kinds of high level sup

port and a particular orientation on the part of the public and

the school officials to meet each child in this way (271a).

Dr. Tracey went on to testify why the County was not providing this

support and why the proposed program of the City would.

14

and to his study of the existing and proposed systems to as

certain which was more likely to provide that effort. In his

study, Dr. Tracey examined “the organizational pattern and

effects on that organizational pattern of the separate or pos

sible separate school systems for Emporia” (269a). Such

study necessarily involved a consideration of the racial compo

sition of the two systems. Dr. Tracey did testify that “no

particular pattern of mixing has in and of itself, has any

desirable effect” (270a). He also testified that he knew of

no study that would indicate whether an increase in the ratio

of Negro to white children from 60-40 to 70-30 would have

any effect on the educational process (281a).

In summary, the City has committed itself to assign all

elementary pupils in the City to one school building and all

high school pupils to one school building; to assign faculty

on a completely integrated basis; to rename the former Em

poria Elementary School the R. R. Moton Elementary

School; to accept no students from other school divisions or

districts until approval is obtained from the District Court

(224a, 225a).12 Further, it has committed itself insofar as

12 The following resolution was adopted by the City School Board

and filed as the plan under which it proposed to operate if permitted

to do so (Ex E-F, Flearing of December 18, 1969, 224a) :

_ Mr. Lankford introduced the following Resolution, which after con

siderable discussion by the Board, was unanimously adopted:

If permitted by the United States District Court to operate

its own school system, the School Board of the City of Emporia

will do so according to the following plan:

1. Assignment of pupils and faculty shall be made on a com

pletely racially integrated basis resulting in a racially unitary

system. All pupils of the same grade in the system shall be as

signed to the same school, with the possible exception of those

pupils assigned to a special education program which program

will be conducted on a racially integrated basis. It is contem

plated that all grades, kindergarten through the sixth grade, shall

be located and conducted in one building (the former Emporia

Elementary School to be renamed R. R. Moton Elementary

School) and all grades, seventh through twelfth, shall be located

15

possible to operate a quality system designed to meet the

problems that naturally occur in the transition from a basic

ally segregated system to a massively integrated one.

The City system would contain 580 Negro children and

543 white children—a ratio of 52% Negro to 48% white.

The County system would contain 1,888 Negro children

and 728 white children—a ratio of 72% Negro to 28%

white. The combined systems contained 2,477 Negro chil

dren and 1,282 white children—a ratio of 66% Negro to

34% white (304a).

Petitioners introduced no evidence in this case indicating

any dissatisfaction on their part with the City’s plan to oper

ate its unitary school system.13

Its evidence at the hearing on August 8, 1969 upon the

motion for a temporary injunction was restricted to testimony

from the superintendent of schools, the mayor of the City,

and the chairman of the City School Board together with

exhibits introduced through those witnesses. At the hearing

on December 18, 1969 to determine whether the injunction

should be made permanent, it was stipulated that the evi

dence introduced at the August hearing could be considered

and conducted in one building (the former Greensville County

High School to be renamed Emporia High School).

2. The schools will sponsor and support a full range of extra

curricular activities and all activities conducted by or in the

public school system will be on a racially integrated basis.

3. Any bus transportation that is provided will be on a racially

integrated basis.

4. No students will be accepted from other school divisions or

districts until approval is first obtained from the United States

District Court.

13 The record does not disclose the residence of the petitioners at

the times pertinent to the issues here involved—thus, it is not known

whether they all resided in the County, whether they all resided in the

City, or whether some resided in City and some in the County.

16

as received in the December hearing (Transcript of proceed

ings, 12/18/69, p. 3). Petitioners introduced no additional

evidence.

Decision of the District Court

On page 17 of their brief, petitioners quote at length from

the opinion of the District Court delivered from the bench

on August 8, 1969 at the hearing on the temporary injunc

tion.

There can be no doubt that the District Court’s impression

of this case at the time of that hearing changed drastically

after hearing the evidence presented by the City on Decem

ber 18, 1969. During the hearing on December 18, the Dis

trict Judge stated:

f think the matter now is in a different posture and

less difficult in the calmness of December than it was

(240a).

* * *

* * * j sajc} before, this is a much—a more dif

ferent situation than it was in August (248a).

Therefore, it is the findings made by the District Court

after the evidence was fully developed that are controlling.

Certainly, they supercede any conflicting findings made after

the expedited and peremptory hearing on the temporary

injunction. It is to the later findings we now turn.

(a ) P roposed Sy s t e m

With respect to the system Emporia desires to operate, the

District Court found:

The city clearly contemplates a superior quality edu

cational program. It is anticipated that the cost will be

such as to require higher tax payments by city residents.

17

A kindergarten program, ungraded primary levels,

health services, adult education, and a low pupil-teacher

ratio are included in the plan, defendants’ Ex. E-G

at 7, 8 (297a).

* * *

The Court does find as a fact that the desire of the

city leaders, coupled with their obvious leadership abil

ity, is and will be an important facet in the successful

operation of any court-ordered plan (306a).

* * *

This Court is satisfied that the city, if permitted, will operate

its own system on a unitary basis (307a).

(b ) R e a so n s for E m po r ia ’s D e c isio n

W ith respect to the reasons behind the desire of Emporia

to operate its own system, the District Court found:

The motives of the city officials are, of course, mixed.

Ever since Emporia became a city consideration has

been given to the establishment of a separate city sys

tem (305a).

•3£ ‘Jf

Emporia’s position, reduced to its utmost simplicity,

was to the effect that the city leaders had come to the

conclusion that the county officials, and in particular

the board of supervisors, lacked the inclination to make

the court-ordered unitary plan work. The city’s evidence

was to the effect that increased transportation expendi

tures would have to be made under the existing plan,

and other additional costs would have to be incurred in

order to preserve quality in the unitary system. The

city’s evidence, uncontradicted, was to the effect that

the board of supervisors, in their opinion, would not be

w illin g to provide the necessary funds (305a, 306a).

* * *

The Court finds that, in a sense, race was a factor

in the city’s decision to secede (307a).

18

It is significant that while the District Court found the

motives of the city officials to be mixed and that, in a sense,

race was a factor, it did not find that the reasons of the City

were related to obtaining “a more palatable racial mix”

(PB 54).

(c ) E f f e c t o n C o u n t y

W ith respect to the effect of the establishment by Emporia

of a separate system, the District Court found:

The establishment of separate systems would plainly

cause a substantial shift in the racial balance. The two

schools in the city, formerly all-white schools, would

have about a 50-50 racial makeup, while the formerly

all-Negro schools located in the county which, under

the city’s plan, would constitute the county system,

would overall have about three Negro students to each

white [footnote omitted] (304a).

* * *

Moreover, the division of the existing system would

cut off county pupils from exposure to a somewhat more

urban society (306a).

* * *

While the city has represented to the Court that in

the operation of any separate school system they would

not seek to hire members of the teaching staff now

teaching in the county schools, the Court does find as a

fact that many of the system’s school teachers live with

in the geographical boundaries of the city of Emporia.

Any separate school system would undoubtedly have

some effect on the teaching staffs of the present system

(307a).

In sum, the District Court was primarily concerned with

the shift in racial balance that would result if Emporia estab

19

lished its own system. Secondarily, it commented upon the

county pupils’ exposure to a somewhat more urban society1*

and an unspecified effect on the teaching staffs. It was upon

those factors alone that the District Court prohibited the

City from exercising the powers and fulfilling the duties im

posed upon it by the law of Virginia.

In concluding its opinion, the District Court clearly indi

cated that it considered any possible adverse effects result

ing from separation to be purely speculative:

But this [fact that Emporia’s system will be unitary]

does not exclude the possibility that the act of division

itself might have foreseeable consequences that this

Court ought not to permit (emphasis supplied) (307a).

* * *

This Court is most concerned about the possible ad

verse impact of secession on the effort, under Court di

rection, to provide a unitary system to the entire class

of plaintiffs (emphasis supplied) (308a).

Having decided to prohibit Emporia from establishing its

system for the reasons recited above, the District Court

added:

If Emporia desires to operate a quality school sys

tem for city students, it may still be able to do so if it

presents a plan not having such an impact upon the

rest of the area now under order. * * * Perhaps, too, a

separate system might be devised which does not so

prejudice the prospects for unitary schools for county

as well as city residents. This Court is not without the 14

14 According to the 1970 census, Emporia had a population of

5300. U.S. Dept, of Commerce Bureau of Census, 1970 Census of

Population, General Population Characteristics PC ( / )— B 48 Virginia

(October 1971). According to the mayor of Emporia, the wealth of

the area is located in the County and not the City (291a). Thus, the

benefits of being exposed to the “urban society” of Emporia would

appear somewhat limited, at best.

20

power to modify the outstanding decree, for good cause

shown, if its prospective application seems inequitable

(309a).

If the unitary plan proposed by the City does not satisfy

the test of equity, it is difficult to envision how it could be

modified in a manner which would permit the City to accept

the invitation of the District Court.

Decision of the Court of Appeals

The Court of Appeals reversed the District Court and in

structed that the injunction against the City be dissolved. Its

decision was based entirely upon the factual findings of the

District Court. In summary, the Court of Appeals held:

(a) The power of state government to determine the

geographic boundaries of school districts is ordinarily

plenary (311a, 312a).

(b) Such power is limited when the exercise thereof

is for the purpose of perpetuating invidious discrimi

nation (312a).

(c) If the effect of the boundary determination is

resegregation, a discriminatory purpose will be inferred

(312a).

(d) If the effect of the boundary determination is

only a modification of the previous racial ratio, then

further inquiry into the purpose of that change must be

made (313a).

(e) Relying only upon the findings of fact made by

the District Court, the Court of Appeals held that

neither the effect nor the purpose of the boundary de

termination was in violation of the constitutional rights

of petitioners (316a).

The decision of the Court of Appeals will be more fully

discussed subsequently.

21

However, attention is now called to the fact that peti

tioners throughout their brief refer to the Court of Appeals

as having given consideration to the motive of the City

officials in deciding to establish a separate school system

(PB 26, 29, 37, 40, 45, 46). Whether by accident or design,

petitioners inaccurately portray that the Court of Appeals

tested the constitutionality of Emporia’s action by determin

ing the “primary motive” (313a, 316a, 318a) of the local

officials. Of course, it was the “purpose” of the action, rather

than the “motive” behind that action, that was considered

by the Court of Appeals and this is clearly stated in the

opinion. Petitioners attempt to negate the distinction between

purpose and motive by a footnote on page 38 of their brief.

Petitioners quote at length from Judge Sobeloff’s dissent

ing opinion in United States v. Scotland Neck City Board of

Education, 442 F.2d 575 (4th Cir. 1971), stating that it

was a companion case to the instant one (PB 27, 28).

Though the cases were decided at the same time, the Scot

land Neck case is not truly a companion to the Emporia case.

They were tried by different district courts and involve sub

stantially different facts.10

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

I

Under the law of Virginia counties and cities now are and

historically have been independent of each other politically,

govemmentally and geographically. Each has the separate

16 Judge Sobeloff did not participate nor vote in the Emporia case.

If any significance can be attached to his views so far as this case is

concerned, then it should be noted that Judge Butzner, who likewise

did not participate in it, was a part of the majority in the United

States v. Scotland Neck City Bd. of Educ., and must, therefore, be

assumed to be in accord with the principles set forth by the majority

in the Emporia case.

22

and independent right and duty to operate and maintain

its own school system. Emporia became a city on July 31,

1967 pursuant to a law that has existed since at least 1892

and, at that time, became obligated to maintain its own

school system.

II

The proposed action of the City to operate and maintain

an independent school system will not violate any of the con

stitutional rights of petitioners as those rights have been de

fined by the most recent decisions of this Court. The constitu

tional rights of petitioners, which in this case are grounded

upon the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment, require that they be permitted to attend a unitary,

non-racial system of public education. The corresponding

duty of the local school authorities is to provide such a sys

tem. Petitioners are not entitled to demand, and local school

authorities are not required to provide, any particular plan

to accomplish that result.

In this case, the proposed action by the City of Emporia

will result in a racially unitary system of public education

in the City in which approximately 52% of the school popu

lation will be Negro and 48% will be white. All students in

the elementary grades will attend one school and all students

in the high school grades will attend another school. The

County system, which will also be racially unitary, will con

tain approximately 72% Negro students and 28% white

students. The ratio of the combined system is approximately

66% Negro and 34% white. The shift in racial balance re

sulting from the proposed separation of Emporia from the

County system denies to no one any constitutional right to

which he is entitled. Further, no other result of the proposed

separation constitutes the violation of any constitutional right

of petitioners.

23

The proposed action of the City will stand any constitu

tional test to which it is fairly subjected whether that test

be the one announced in the opinion of the Fourth Circuit,

the one proposed by Judge Winter in his dissent to the

opinion of the Fourth Circuit, or the one proposed by Judge

Sobeloff in his dissent to the opinion of the Fourth Circuit in

United States v. Scotland Neck City Board of Education,

supra.

Therefore, the City of Emporia should not be restrained

from exercising the powers and fulfilling the duties imposed

upon it by the Constitution and laws of Virginia.

ARGUMENT

I

The Law of Virginia Vests the Power and the Duty Upon the City

of Emporia to Operate and Maintain a Public School System

A.

C o u n t ie s A nd C it ie s O f V irg in ia A re

I n d e p e n d e n t O f E a c h O t h e r

In City of Richmond v. County Board, 199 Va. 679

(1958) at 684, the Supreme Court of Virginia stated:

In Virginia, counties and cities are independent of

each other politically, governmentally and geographi

cally. Each of them, within its particular boundaries,

is a co-equal political subdivision agency of the State.

In Murray v. Roanoke, 192 Va. 321 (1951) at 324, the

Virginia Court held:

In Virginia, counties and cities are separate and dis

tinct legal entities. Each is a subordinate agency of the

State government, and each is invested by the legisla

24

ture with subordinate powers of legislation and adminis

tration relative to local affairs in a prescribed area. Citi

zens of the counties have no voice in the enactment of

city ordinances, and conversely citizens of cities have no

say in the enactment of county ordinances.

That this has been the law historically in Virginia is

demonstrated by Supervisors v. Saltville Land Co., 99 Va.

640 (1901).

This principle is applicable to a city that became such

under the provisions of the law providing for the transition

of towns to cities. In Colonial Heights v. Chesterfield, 196

Va. 155 (1954), the Supreme Court of Virginia held at 167:

The town, upon becoming a city, separates from a

political subdivision of which it was a part and be

comes an independent political subdivision, except as to

certain joint services specified in Code, § 15.104 [now

§ 15.1-1005],

Schools are not listed among the services specified in

§ 15.1-1005—that section is limited to the sharing of the

circuit court, commonwealth’s attorney, clerk and sheriff.

B,

E m poria Beca m e A C ity P u r s u a n t T o

L o n g E x is t in g Sta te L a w

The present Code of Virginia provides that a town upon

attaining a population of 5,000 may elect to become a city of

the second class by following the procedure set forth in the

Code. Title 15.1, ch. 22, Va. Code Ann. 1950, as amended.

The law has been substantially the same since at least 1892.

Acts of the Assembly, 1891-1892, ch. 595, at 934.

Thus it is clear that the provisions under which the Town

of Emporia acted to become a city have long been a part of

25

the law of Virginia and were not enacted in any way as the

result of the school desegregation suits or for any other racial

reason.

G.

C it ie s I n V irg in ia H ave T h e R ig h t A n d D u t y T o

O per a te A n d M a in t a in O w n S ch o o l Sy s t e m s

On July 31, 1971, a rather extensive revision of the Con

stitution of Virginia became effective. Conforming revisions

to the statutes of Virginia likewise became effective on that

same date. The argument that follows in this section is ap

plicable under the constitution and statutes both before and

after the revision.

The Constitution of Virginia has, since 1928, vested the

supervision of county schools in the county school boards and

the supervision of city schools in the city school boards. Sec

tion 133 of the Constitution of Virginia (RA 1), which

was in effect at the time this case was tried,16 provides, in

part, as follows:

The supervision of schools in each county and city

shall be vested in a school board, to be composed of

trustees to be selected in the manner, for the term and

to the number provided by law.

Since at least 1919 the Code of Virginia has affirmatively

required the city school boards to establish and maintain a

16 Pertinent portions of the Constitution as revised are set forth at

RA 2.

Many of the sections of the Code of Virginia which are set out in

the appendix to the Brief for Petitioners have been amended or re

pealed. The sections, as amended, are set forth at RA 2, 3 and 7.

Under the law of Virginia at the time this case was tried and at

the present time, it was and is not possible to have a single school

board for a county and a city without the consent of both and of the

State Board.

26

system of schools in cities. Section 22-93, V a. Code Ann.,

1950, as amended (RA 3), provides:

The city school board of every city shall establish

and maintain therein a general system of public free

schools in accordance with the requirements of the Con

stitution and the general educational policy of the Com

monwealth.

This language was also contained in the Code of 1919,

§ 786.

Section 22-97, Va. Code Ann., 1950, as amended (RA

3, et seq.), enumerates the powers and duties of the city

school boards.

Thus, the law in Virginia for many years has not only per

mitted but required city school boards to establish and main

tain city schools.

The petitioners have recognized that the local school

boards are required to “establish, maintain, control and su

pervise an efficient system of public free schools” in the

political subdivisions of the State. See paragraph 7 of the

Complaint filed on March 12, 1965 (5a).

The Supreme Court of Virginia has spoken directly to

the duty of a city to maintain its own school system after

a transition. In School Board v. School Board, 197 Va.

845 (1956), dealing with the transition of the Town of

Covington to a city, the court stated at 847:

As a town, Covington was a part of Alleghany County

whose public schools were operated by the County

School Board. When Covington became a city it ceased

to be a part of the county, became a completely inde

pendent governmental subdivision, and was required by

law to maintain its own public school system (emphasis

supplied).

27

The evidence shows that under the contract arrangement

between Greensville County and the City of Emporia, which

was in existence when the case was tried in the District

Court, the School Board of the City of Emporia was not

exercising or fulfilling any of these powers and duties (158a,

159a, 242a).

If the City is further restrained from operating its own

system, an intolerable situation will be perpetuated. Children

of City residents will be required to attend a school system

over which the City has absolutely no control. The City will

have no right to participate in the selection of the members

of the County School Board and thus will have no voice in

the quality of the schools that are provided. It will have no

right to participate in the selection of the governing body of

the County and thus will have no voice in the amount of

money appropriated for school purposes.

On the other hand, the County will be required to con

tinue educating the City’s children. Absent agreement be

tween the City and County, there is no definitive provision

for establishing the amount that City should pay to the

County for this service. If no such agreement could be

reached—and with the situation as it exists, it is doubtful

that it could—the question would inevitably be presented to

the courts. Any order requiring the City to pay a certain

amount to the County would, in effect, be an order requiring

the governing body of the City to levy taxes and appropriate

a fixed sum to pay to the County for the operation of its

school system—a school system over which the City has no

control whatsoever.

On page 45 of their brief, in footnote 26, petitioners sug

gest a solution: they suggest that the District Court “could

modify the requirements of state law concerning representa

tion.” They do not elaborate on this plan. Do they envision

28.

court-ordered representation of the City on the school board

only? This would accomplish nothing since the power of the

purse lies solely with the governing body of the County. Or

do they suggest court-ordered representation of the City on

the governing body of the County? The statement of the

question alone illustrates the problems—constitutional, statu

tory and practical—which would inevitably follow.

If petitioners’ suggestion were followed to its logical con

clusion, district courts would find themselves making legisla

tive determinations involving every level of state government.

They would be required to determine the manner in which

local government in Virginia must be structured, the manner

of providing representation on the governing bodies and

school boards of the local units of government, and the man

ner in which the taxing powers of those units must be exer

cised.

We do not believe that the operation by Emporia of its

own school system as provided for by Virginia law violates

any constitutional right of petitioners. And we submit that

the fact that the structure of local government in Virginia

was established under long-existing constitutional and statu

tory provisions is a consideration upon which this Court

should focus in deciding this question.

II

Operation by the City of Its Own School System Would Violate no

Constitutional Rights of Petitioners

A.

P e t it io n e r s ’’ R ig h t s

Petitioners’ rights in this case are grounded upon the man

date contained in the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States that:

29

No state . . . shall deny any person within its juris

diction the equal protection of the laws.

Between the date of the decision in Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) (Brown I ) , and the present

time, literally hundreds of cases have been decided dealing

with the scope of this constitutional mandate as applied to

the public school systems of the several states. Nevertheless,

it is well to focus on the language of the basic provision of the

Constitution which establishes the rights of the petitioners on

the one hand and the duties of the respondents on the other.

In Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 402

U.S. 1 (1971), Green v. School Board of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968), and in Alexander v. Holmes County

Board of Educ., 396 U.S. 19, (1969), this Court has made its

most recent pronouncements with respect to the substantive

constitutional rights of Negro children and the corresponding

duties of local school boards.

In Green, the Court stated that it had held dual systems

unconstitutional in Brown I and that the school boards were

“required by Brown II ‘to effectuate a transition to a racially

non-discriminatory school system’.” 391 U.S. at 435.

The Court then said:

\T]he transition to a unitary, non-racial system of

public education was and is the ultimate end to be

brought about . . . (emphasis supplied).

391 U.S. at 436.

The Court continued:

School boards . . . were . . . charged with the af

firmative duty to take whatever steps might be neces

sary to convert to a unitary system in which racial dis

crimination would be eliminated root and branch . . .

30

The constitutional rights of Negro children articulated

in Brown I permit no less than this . . .

391 U.S. at 437, 438.

In Holmes, this Court instructed the Court of Appeals to

declare:

that each of the school districts here involved may no

longer operate a dual school system based on race or

color, and directing that they begin immediately to

operate as unitary school systems within which no per

son is to be effectively excluded from any school because

of race or color.

396 U.S. at 21.

In Swann, this Court did not expand its previous defini

tion of the rights of Negro children but rather dealt with

the duties of school authorities and the powers of district

courts to assure that such rights were enjoyed. The objective

of the Court was “to see that school authorities exclude no

pupils of a racial minority from any school, directly or in

directly, on account of race.” Swann, 402 U.S. at 23. (I t is

to be noted that in the instant case, petitioners are in the

racial majority.)

Therefore, based upon the foregoing decisions, the peti

tioners have the constitutional right to attend a unitary, non-

racial school system, and the local school boards have the

affirmative duty to provide such a system. It is submitted

that while the petitioners can expect no less, they can de

mand no more. Such a system is “the ultimate end,” {Green,

391 U.S. at 436) to be attained and, if attained, provides the

rights to which petitioners are entitled and fulfills the duties

for which the respondents are responsible.

This Court has also held that Negro children have no con

stitutional right to any particular plan to accomplish the

31

ultimate end of a racially unitary system. If the plan of the

local school authorities has been adopted in good faith and

“promises realistically to work now,” then it provides effec

tive relief. Green, 391 U.S. at 439. And school authorities

“have broad power to formulate and implement educational

policy” Swann, 402 U.S. at 16.

Of course, the right to a unitary, nonracial school system

cannot be nullified “through evasive schemes for segregation

whether attempted ‘ingeniously or ingenuously’.” Cooper v.

Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) at 17. By the same token, the

rights and duties of local school authorities to operate and

maintain school systems as provided for by the constitution

and laws of the state cannot be nullified by insistence upon

a particular method of achieving a unitary system.

It is only when the violation of a constitutional right has

been shown that the remedial powers of the courts may be

exercised. In Swann, this Court stated:

In seeking to define even in broad and general terms

how far this remedial power extends it is important to

remember that judicial powers may be exercised only

on the basis of a constitutional violation. Remedial ju

dicial authority does not put judges automatically in the

shoes of school authorities whose powers are plenary,

judicial authority enters only when local authority de

faults.

402 U.S. at 16.

Here, the City has not defaulted and its proposed action

will not violate any of petitioners’ constitutional rights. Thus

it is not necessary, nor is it proper, to consider the scope of

the district court’s remedial power. Where there has been

no denial of a federally protected right, there is no remedial

power to be exercised.

32

B.

P ro posed A ctio n O f T h e C ity

The School Board of the City of Emporia has adopted a

plan pursuant to which it will operate a racially unitary

school system if permitted so to do by the courts. This plan

is set forth in footnote 12 on page 14 of this brief and on

page 224a of the Appendix.

The evidence shows that such a system operated by the

City will have approximately 48 percent white students and

52 percent Negro students (304a).

The uncontradicted evidence showed that the City has

taken steps to plan a school system of excellence that would

provide incentives for all its children to obtain an education

in a truly unitary system. The District Court so found

(297a). It was envisioned that this system would serve as

an example of what can be done by school officials dedicated

to making a unitary system work—not just in name and

numbers, but in actual fact.

The School Board engaged the services of a well-known

educator who assisted it in making preliminary plans for the

type of program that would be required to meet the educa

tional and social challenges of a system that has a 50-50

racial mix and to hold the children who might otherwise

drop out of the system before completing their education

(202a, et seq. espec. 212a). An estimated budget for the

operation of such a system was prepared and approved by

the unanimous vote of the School Board (200a). Further,

the City Council agreed to include the necessary funds to

finance such a system in the next budget (287a). Of course,

the actions of the School Board and Council were necessarily

conditioned upon the dissolution of the injunction entered

by the District Court.

33

Every step that could practicably be taken to plan such a

system consistent with the restraints imposed by the District

Court was taken. The plans were more than mere abstract

expressions of individuals relating to goals to be sought.

Formal approval to the extent now possible of workable

plans and the estimated budget by the respective Boards are

a matter of record. If those plans violate no constitutional

rights of petitioners, then the Council and School Board, of

the City of Emporia should be permitted to proceed to put

them into effect.

C.

P e t it io n e r s ’ R ig h t s W il l N ot Be V iolated By T h e

P roposed A ctio n O f T h e C ity

It is obvious that the separate systems— City and County

■—will each be racially unitary in law and in fact. No stu

dent in the City and no student in the County—whether of

the racial majority (Negro) or minority (white)—will be

excluded from any school on account of race. The District

Court held that it “was satisfied that the City, if permitted

will operate its own system on a unitary basis” (307a). It

previously entered an order that assures such a system will be

operated in Greensville County (54a) regardless of the out

come of this case.

In footnote 21, on pages 32 and 33 of their brief, peti

tioners complain that under the City’s plan the traditional

racial identities of the schools would be maintained. This is

just not true. For two and one-half years, the County system

has been operated under the “pairing” plan approved by the

District Court on June 25, 1969 and presumably it would

continue to operate under such a plan. Under the City’s pro

posal, each of the two schools it will operate will be fully

integrated—one with a slight majority of Negro students,

34

the other with a slight majority of white students (316a).

And one of those schools will be named the R. R. Moton

Elementary School (225a).

Therefore, it is only if the separation itself, which came

about as an automatic and incidental result of the town’s

transition to city status, deprives petitioners of their constitu

tional rights that the City should be prohibited from operat

ing its own system as every other city in Virginia is permitted

to do.

Petitioners base their argument and their case on an as

sumption. They assume the deprivation of a constitutional

right. They do not ever attempt to point out the constitu

tional right they claim would be violated. Their argument

speaks only to the remedial powers of the District Court

which, as we have previously noted, can only be applied

after a violation of a constitutional right has been shown.

■Swann, supra, 402 U.S. at 16. Thus, petitioners attempt to

pull themselves up by their own bootstraps—they argue the

abstract principles with respect to remedy without ever

establishing a violation.

To put the issue here involved into perspective it is neces

sary to examine the reasoning of the District Court and of

the dissenting judge (Judge Winter) on the Court of Ap

peals in holding that the City should be restrained. Only in

that way can the applicable law be related to the facts in this

argument. In their Statement, petitioners set forth the

following “difficulties” which the District Court found would

arise upon separation (PB 21, 22) :

1. substantial shift in racial balance,

2. a city high school of less than optimum size,

3. isolation of rural county students from exposure

to urban society,

4. disruption of teaching staff, and

35

5. withdrawal of city leadership from the county’s

educational program.

Further, they set forth the factors mentioned by Judge

Winter which would make the separate system plan “less

effective” than the District Court order. In summary, these

factors were stated to be (PB 27) :

1. delay which would be occasioned by adoption of

new plans,

2. substantial change in racial proportions, and

3. the effect on county black students of the excision

from their system of a significant part of the white

population.

W ith the exception of the so-called “substantial shift” in

racial balance, all of the aforementioned “difficulties” and

factors would be present even if the racial balance in the

separate systems had remained precisely the same as it was

before separation. And almost all of them would be present

had the systems historically been separate.

We submit that none of such difficulties or factors—even

if they in fact exist, which we deny—constitutes a violation

of any constitutional right of petitioners. We again point out

that the District Court was not convinced that any adverse

effects would result from the separation. It stated that even

though the City would operate systems with “superior qual

ity” (297a) on a “unitary basis” (307a), that

[But] this does not exclude the possibility that the act

of division itself might have foreseeable consequences

that this Court ought not to permit” (emphasis sup

plied) (307a).

And:

This Court is most concerned about the possible ad

verse impact of secession on the effort, under Court di

36

rection, to provide a unitary system to the entire class

of plaintiffs” (emphasis supplied) (308a).

It is clear that the primary factor upon which the Dis

trict Court based its decision, upon which Judge Winter

based his dissent and upon which petitioners base their case

is the shift in racial balance that will occur. We will address

that issue now.

Shift in racial balance

The facts with respect to racial balance are :

Combined system 66% black; 34% white

Separate systems

Countv ..................................... 72% black; 28% white

C ity ........................................... 52% black; 48% white

These are the facts found by the District Court and

adopted by the Court of Appeals (304a, 316a). Whether or

not such a shift of such ratios constitutes the violation of a

constitutional right is not a question of fact—rather it is a

conclusion drawn from the facts. It is certainly within the

powers of courts of appeals to reverse district courts on such

a matter. Glassman Construction Company v. United States,

421 F. 2d 212 (4th Cir. 1970). Actually, the District Court

did not ever specifically hold that the shift did constitute a

violation of constitutional rights.

In any event, we submit that a six percent increase in

Negro enrollment and a six percent decrease in white enroll

ment cannot reasonably be deemed a “substantial shift.”

Such a minor change of proportions could result in any year

for a variety of reasons and could not be deemed to alter the

character of the County system. Before and after such a

shift, the County system would be fully integrated with an

approximate two to one Negro to white ratio.

37

We submit that there is no evidence in the record to indi

cate that such a slight shift would actually result in any harm

to county students. However, assuming arguendo, that harm

would result from this slight change in the racial balance,

per se, is it the type of harm against which the Constitution

of the United States provides protection? The City submits

that it is not. It does not result from the deprivation by the

City of any constitutional rights of the petitioners.

In Swann, 402 U.S. at 24, this Court made it crystal clear

that there is no requirement “as a matter of substantive con

stitutional right, [to] any particular degree of racial balance

or mixing.” It continued:

The constitutional command to desegregate schools

does not mean that every school in every community

must always reflect the racial composition of the school

system as a whole.

402 U.S. at 24.

While local school authorities could require such ratios,

federal courts do not have the power to do so absent a find

ing of constitutional violation. Swann, 402 U.S. at 16.

Analysis of the cases cited by petitioners discloses that they

are readily distinguishable from the Fourth Circuit’s decision

in this case. It is probable that had those cases been before

the Fourth Circuit, its decision would have been the same as

in the cited cases.

In Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., No. 30154 (5th

Cir., June 29, 1971) (SA la), Oxford City, Alabama, at

tempted to establish its own school system independent of

Calhoun County of which it is a part. Apparently, Oxford