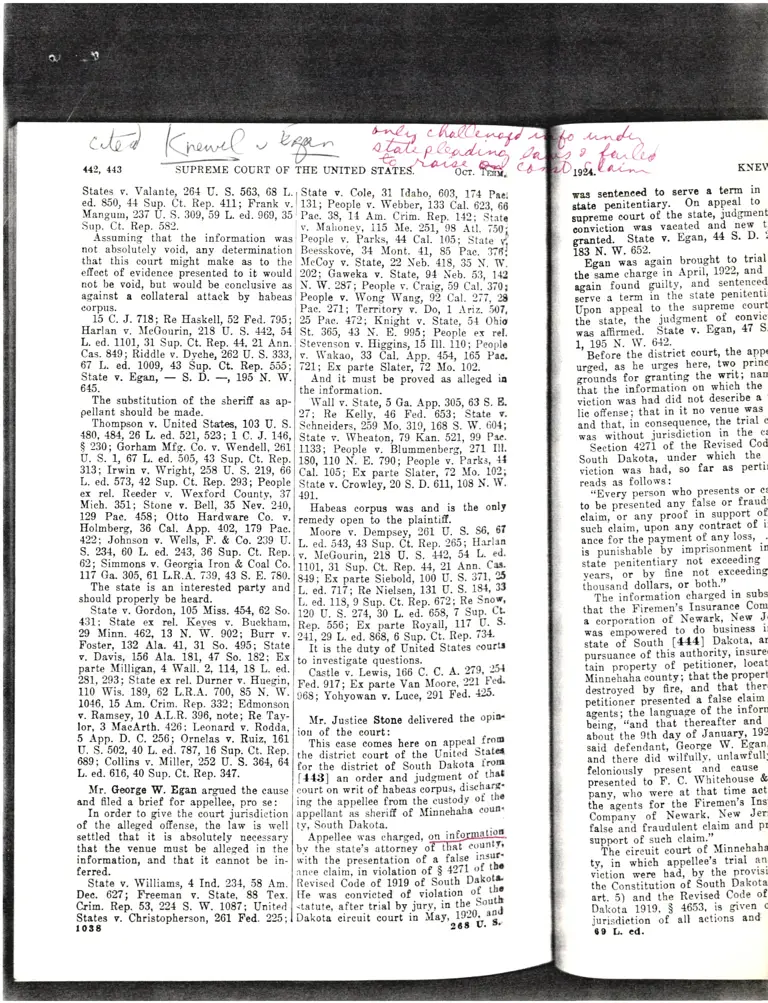

Knewel v. Egan Court Opinion

Working File

January 1, 1925 - January 1, 1925

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Knewel v. Egan Court Opinion, 1925. 6fdea965-ed92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/545464b7-ba47-456b-936f-927aad57420b/knewel-v-egan-court-opinion. Accessed January 24, 2026.

Copied!

( "L7 @c r off-,^. ry?j!?:;ffi,

-supRElrE couRr oF rEE uMTED srafus.@dr. H ca

Slat^ers^v..Yalante,26_{ U. S,5Q,68 L.rState v. Cole, 31 ldabo, 603, 17{ pac.

ed. 850, {-1^!r_9. Ct._Rep-^4_11 ; Frank

-v-.t13t; People v. Webber, igg Cat. OZl, eO

!Iangqm,_z37 U_. !.309,59 L. ed.969,35rPac. 38, 11 Am. Crim.'Rep. 112; Siati

Srrp. Ct. Rep. 53!. 'v. -\[ahone.v, 115 ]Ie. gb1,'98 ,Ltt. ;;O:

Assuming that the information was People v. parks, 44 Cal.'105; State ii

not absolutcly void,, any determination I Beesskovb, 34 }Iont. 41, 8b pae. j?S{

that this court might malie as to the' l{cCoy v. State, 22 Neb.' 418, 35 N. W.

ellect of evidence pres_ented to it would 202; Gaweka v. State, g1 \f;b.53, 1.12

not.be void, blt woulcl be conclusive aslX. W.287; People v. iraig,59 Cal.'3?01

against a collateral attack by habeas I People v. \Yon! Wang, 9I' Cal. 2i7, 2licorpus. iPae.271; Territory v. Do,1.\ri2.507,

_1q C.J.718; Re Ilaskell,52 Fed.795;i25 Pac. 472t Knight u. State, i-t Ohio

$ar!a1-v-. llcGourinr 2!S U. S. 442, 51lSt. 365, 43 N. E: 99S; peopie ex rcl.

142,443

645. lthe information.

The substitutioa of the sherifr as ap-

-ll.arlan

v. .i\rcuourrnl 215 U. S. +42, b4iSt. 3ti5, 43 N. E. 995; people ex rcl.

L. ed. !01 31 Sup. Ct. Rep.44,21 Ann. lstevenson v. Iliggius, f5 nt. ifOl peoplc

Cas.849; Ri{fle v.-Dyche, ?62y. S.333,1v. \Yakao, ffi e;1. App. 4b1, iOS pic.

67 L. eil._1009,43-Sup. Ct. Rcp. 555;1721; Ex parte Slater,'?Z Uo. lOZ.

State v. Egan, - S.D. -, 195 N. W. l And it-must be proved as allegetl il

\Ya-ll v. State, 5 Ga. App. 305, 63 S. E.

pellant shoulil be made.llant should be made. | 27; Re Kelly. 46 Fed. 653; State v.

Thompson v. Ilnited Sist€s, 103 U. S.l Sehneiders. Z5g Mo. 319. 168 S. W. COf ;

27; Re Kelly, 46 Fed. 653; State v.

Schneiders, 259 IIo. 319, 168 S. IY. 60{;

*89.^ae, 29 L. :9.- 52r-., 523; t C.- .I-: 1_19 | State v. \vheaton, 79 Kan. b21, 99 pre.

$ 230; Gorham Mfg. Co. v. Wendell,261 l1133; people v. blummenbers.'271 Ill.

vaL, ae!, r v. vr arvrl a[ale v. t

$ 230; Gorhq }-tfq. 9o. v. Wendell, 261ltta3; peog 23_0; Gorham Mfg. Co. v. Wendell.261 i1133; people v. i3lummenberg, 2Zl Ill.

g-.^S._1, pZ L.gd..5-05,^4_3- Q_up.C_t,R.p-ltgO, irO N'. E. 290; people v."Farks, {{^U_.-S._1,,

p7 L. gd.. 505,

^4_3^ t_rp. Clr

-Rep. l 190, 110 N-. E. 290; people v. parks, {{

313;-Irwin y: T.ig{r !18 U:^q. 2_19, q6lCat. rOO; Ex parre Slatlr, ?2 Uo. 102-;

L. ed.-573, a! Sup.9.E"p, 2_93; People jStot"

".

Crowley, Z0 S. D.611, 108 N.lY.

er rel. Reeder v. Wexford Countv, 37 I lOf ,

Mich.351 ; Stone v. Bell,-35 Nev.2{0, 1 8"b.". corpus was and is the only

129 !ac. 458; -Otto Eardwar.e-^Co. v. lremedy op.o 'io the plaintiff.

4^o-1m!e1s, 36 Ctt $pp. 402,^t79^^pry.1 M;o;"'r. Ou.pr.y,261 U. S. s6,6I

!221_Johlso_n v.-Wells,T. & Co.239 U.lL. ed.;+9, +a $p. ii. Rep.265; rl:,lrn

S, 294, 60 L. err. 243;'86 s,p. ct. n.p

I ;j it;d;il1,- ;i5 ;:'s^:"iii,:i l;_;:

62; Simmons-1._Glorgia_Jlon & Coal_Co.lrior,31 Supl Ct. Rep. {{,21 Ann. Cos.

117-Ga.305,61 LR.A. i39,4g S. E.780-ls+s;'nipuii. Si.uor[, 100 U. S.3i1,?I

The state is an interested party

""a li. .a."ziil ril Nil;;;] iii U: 5. isr, $

should properly be hearil. I L. .a. ffS.'S Suo. Ct. t[eo. 672; Re Snor,should prop-erly_ be heard. I l. .a. ttS, g Sup. Ct. I[ep. 672; Re Snor,

.-_Stat^e v. Gordon, 108 Miss. ry,q? So.lrzo ri-S.'zti,io i. .al osa, z Qrp, *431: _State er rel. Ke.y_es

^v^.^

Buckham, lRep. bS6; Ei p.rte Royall, 1lZ q.. S.431:_State er rel. Ke.v_es

^v^.^

Buckham, lnlp.-SSO; n; p;rt" Royall, lt7 q.. S.

29 }finn. i162, t3 N. P^902.; Burr o.l:+i,29 L.'ed. aO'a, O Sup.'Cr.'Rep.73{.

Foster,. 132,A1a. 41, 31 ,!or495; Statel ii i. the duty of Uoit"a States eouru

v. Davi_s, 156 Ala. 181,J1!:.-t^A!r n.xlto in*Jgut. io.idoor.

?iii*}1'li?il;"ll.i'l3i,iif',,."*"u'i l ";';li,*';i?.'+'",'r,!;,1,

,Ti3$

lllr,\;'ff:,.?i.:#;;- Jf* $i;I^),".; i;d;;

y;biy;#'."r.i,.i isi FLa. e5'

.r.u*o, 10 -q.rn.. urlm._ t(ep.- JJz; -Ejdmonson

I

i;"liTr?#f lrl ll?#:l' i

-fi

"I:I I, ^.y

.^r r.,,*'::.lp"o crerivere tr the o p i o'

I_e_pp, p. q. zsof qdlli:,:"I tli,,^-l'"rr"j :*.TH:; here on appear rroo

B,iBt"t-+1*::l,ii."$::i:J6-T"fill::liiq:i, j:rh%"T#,*:#*i

L. ed. 616, 40 Sup. ct. Rep. 347.

I iftsl ",

-oia-.. -"rd jrag*.nr. ot', that

Mr. George W. Egau argueil the cause i ;;r.t t, writ of habeas corpus, disch.irrg'

and filed a brief for appellee, pro se: I ing the appellee frtm the_.custotty o-t^.:::

In order to jiue 1r,e;;;;Jr;i;ai.iion lap-p"tlant^is sheriff of Minnebaha coua'

of the alleged olfense, the law is well I ty, South Dakota.

settled tha[ it is absolutely neeessary |

-

Appellee was eharged, on !nformaLt€

that the venue must be alleged in the I bv the state's attorney of tltat t'1111:::

information, and that it cannot be in- | with the presentation of a false insur'

rerrerl. "" '^'

l,;;;; ;i;i,i'i;"i,"riiii"r-,t S +:zt-"r tu'

State v. \Yilliams, 4 Inil. 23{, 58 Am. ln.''i..,f-d"a. of

-is19

ot Sluth Dakotr

Dec. 627; Freeman v. State.'88 Ter.IH" *". convicted of violation 'I-:l;ucv. waa, t lEEu4u v- dL6Lc. oo h45 gurtvtult

C.rim. Rei. 53,221 S. W. 1087; United l.tatute, after trial by jur.v, io !h^i^-*'15

States v.'Christopherson, 26f F;d. 225;lDakota circuit courf io yar'rtsj06.sil

KI{EV

ras seatcneed to ser-vc a teru in

Jtiie-oenitentiarY. On aPPeal to

;;.d" eourt of-the st-ate, judgment

il'"ri*io" was vaeated and new t

ffi;;-d-.

- State v. Egan, 44 S' D' :

rae N. W. 652.--Er"o was again brought ^to trial

tlf?*" .Urrg"e in APrit, 1C22' and,

seain found guiltY, and sentenceo

;;;; ;1;; in tlie state Penitenti-U-ooo

"PP""t

to the suPreme court

thi stafe, the judgment of convtc

;;;ffi;.d. St.i" v. Egan, 47 s'

1. 195 N. w. Gt2.-'g"for. tbe distriet court, the appt

ureed. as he urges here, two Prtnc

;;;;;h" for grairting the writ; nar

fi;;lh; lnloimatiori-on which the

ui.tlo" ,r". had ditl not describe a

Iic offense; that in it no venue was

"na

tttut, io .on="q'"n"e, the trial c

*""

-*itnoot jurisdiction in the c-:"3..[ioo-+z7i of the Revised Cod

Sorit

--b1f.ota,

under which the.

;t,;i;; -*"i uua, so far as Pertir

reads as follows:

"Every person who-presents-or et

to be presented anv false or fraud'

;i"i;,';;-;;y p'odt in suPPort^o!

such elaim, upon anY contract ot I

""." io. ttre PaYment of anY loss' . '

i.- orni.rrurrti 6Y imPrisonme-nt ir

sta[e penitentiarY not exceedtng

;;;;..'or bv 6ne not exceeding

in-o"trnd doliars, or both'"--il.

info..ation chargecl in subs

tnJine Firemen's Insurance Con

f .t*Li"tion of Newark, New J

*t -J.**.red to do business i:

state oi South [4{4] Dakota' ar

Dursuance of this authorityt lnsure'

irin oroP"rtv of Petitioner' locat

Min".t uir" c6unty;- that the propert

a*i..".a bY firl, anil that ther'

iliti;;;; presentid a false elaim

'"iltii.l *,i tansuage of the info-rn

b:i;;; "';oa

th"at iherearter and .

.u""? tn.ltn daY of January-, 192

."id d.f.ndrnt, George W' Ega.1

antl there did wilfulll-' unlawfull;

feloniorrslv Present nnd eause

r""=".i.d'tr' F. c. \Yhitehouse &

nanv. *lro were at that time act

ih"

"s"nts

for the Firemen's Ins

C-o-*iln, of Newark. New Jer

f"l.; ;n'd fraudulent claim and Pr

suorxrrt o[ sueh claim."--h'ir" .i..rit court o[ ]linnehaha

tY. in wbich aPPellee's trial an

viction were had, bY the Provrsr

the Constitution of South Dakota

;J. ;) ;;e ihe Reviseil code of

Dal<ota 1919. S 4653, is given- c

jo.itai.tioo of all actions and

30 tJ. ed.

ITDD STATES. lgu. KNEWEL v. EGAN. t13-{45

viction was had did not tlescribe a pub- | stance thet the issue of fact in any

lic offense; that in it no venue was laid,lcriminal case can only be tried in the

'. Cole, 31 [daho. 608.

rople v. Webber, iffi Cri'.1.Pi.,

, 1{ Am, Crim. Rep. f {2;Xi.i:

onn', 115 IIe. 251,'gg A l l ?in .

v. P_arks,_ 44 Cal.

'r05.-,{i;t;"'r.:

,ve,3{ I\Iont.4l, m pae. i;|.v. State, 22 Neb.'af S, g5'X.'\i'

l:.kt o.-State, 9{ l(eb. Si,' :q':

f: f i:;f; tg' 3i,:al,'ili

li#H*ur*;:*:+l

""'", " #'ggi :'i il.'l "il,rtl.i*ir parte Slater, 72 Mo. l0Z.it must be proved as alleged iqruation.

v. State, 5 Ga. App. 305, 63 g. B.K"ll]'. 3-0 Fed. ^G53; 'Stuti'i.

I fr ,3XlJiif ?;ilifi, E $,"1:

'e-<.r_ple v. Blummenberg,' 271 I-ll.

: \.E. 790; People r."Frrk.. ;ii; Ex-palte- Slqller, ZZ llo. iOi:

Crosley, 20 S. D. 011, 108 N:Il.:

rs corpus -was and is the oaly

open Co the plaintifr.

1^v..^Dgmpsey, 201 U. S. 56, 6?

13,43 Sup. Ct. Rep. 265; Hailan

rurin, 218 U. S. 412, 54 L. ed.

Sup. Ct. Rep. 44, 21 Ann. Cos.pate S_iebold, 100 U. S. AZ1, Zs

[7; R_e Nie-lsen_, 131 U. S. 181; 3A

-4 9_!op. C_t. R_ep. 672; Re Sno*,

\.2!4,30 L. ed. 658, ? Sup. Cr.

5; Ex parte Ro-vall, 117 U. S.

,. ed. 868, 6 Sup. Ct. Rep.7B4.

be tluty of United States courtr

ligate questions.

v. Lewis, 166 C. C. A.2Tg, Z5l

; Ex parte Van }foore,22l Fed.

ryosan v. Luce, 291 Fed.425.

rstiee Stone ilelivered the opio-

be court:

ase eomes here on appeal from-ict court of the United Statca

ilistrict of South Dakota frou

,n order ancl judgment of tbat

writ of habeas corpus, cliscbarg-

Lppellee from the custod-v of thc

;. as sherifr of Mi.nnehaha coun.

r Dakota.

ee rras eharged, on information

tate's attorney of that eounty,

presertation of a false insur-

nr, in violation of $ 4271 of thc

Code of 1919 of South Dakote.

convieted of violation of t^bc

Lfter trial by jury, in the Souib

ircuit court in May, 1920, ard

2Gt rr. 3.

res sentcDced to serve a term in the, both at law and in equity, and original

rtate penitentiary. On appeal to the I

jurisdiction to try and determine all

mpreme court of the state, judgment of I eases of felonv. It accordingly had-aonviction was vacatcd attd new trial Ilrlenall jurisdiction to try thc charge of

qrantetl. State v. Egan,44 S. D. 2TS,lviolation of S {?71 of the Revised Code,

i3g N. W. 652. lrvhieh nrakes the presentation of false or

Egau was again brought to trial on I fraudulcnt insuranee claims a crime,

tbe

-same ebarge in April, 1922, and was I punishable by imprisonment in tLe state

reain found guilt.r', and sentctteed to ' penitcntiary, which, by $ 3573, is made

sirvo a term in thc slate penitcntiar'.r'. , a {clony. The circuit court is not

Unon appcal to the supreme c'outt of j limited in its jurisdietion by the stat-

the state, the judgment of eonviction I utcs of the state to any particular eoun-

was affirmed. State v. Egan, 47 S. D. I t.v. Its jurisdiction extends as far as

i.-is5 X. W. fr2. I ti,e statuie law ertends in its applica-'Before the distriet court, the appellee I tion; namely, throughout the limits of

urged, as- he urges here, two prineipal I the state. The o-nly lim.itation in this

er6unds for granting the writ; namely,l regard, contained in the statute, is

ihat the information on which the con- | fourrd in $ 4654, which provides in sub-

antl that, in eonsequence, the trial eourt I court in which it is brought, or to which

was without jurisdiction in the cause. I the place of trial is changed by ortler

Section 4271 of the Revised Code of i of the court.

South Dakota, under which the eon- | Section 4771 provides that clefenclant

viction was had, so far as pertinent, I may demur to the information when it

reads as follows: appears upon its face t'that the court

((Every person who presents or eauses I is without jurisdiction of the offense

to be presented any false or fraudulent I charged." Section 4779 provides thft

claim,-or any proof in support of an-"-lobjections to which demurrers may be

such claim, upon ary contiact of insur- I [445] interposed under $ 4771 are

nnce for the navment of anv loss. . | 's'aivetl. with certain exceptions not hereance for the payment of any loss, . |

's'aivetl, with certain exceptions not here

is punishable by imprisonnrent ir the I rnaterial, unless taken by demurrer.is punishable by imprisonnrent ir the I rnaterial, unless taken by demurrer.

stafe penitentiary not exceeding three i Appellee pleaded "not guilty" to thestate penttenttarY

years, or by fine not exceecling one I indictment.. _ _Elis -application., _

macle

ihousand dollars, or both." later, to withciraw the plea and demur,

The information charged in substance I was denietl, the court acting within its

;:rj

that the Firemen's Insurance Company, I diseretionary power. State v. Egan, 47

a corporation of Newark, New Jersel', I S. D. 1, 195 N. W. 642. .The supreme

was empowered to do business in the I court of South Dakota, in sustaining

state of South [444] Daliota, and, in I the verdict and upholding the convio-state of South [444] Daliota, and, in I the verdict and upholding the convio-

pursuanee of this authority, insured eer- | tion, held that the inforrnation suf-

iain property of petitioner, loeated in | ficiently chargecl a public offense under

Minnphahs ennntvr thst the nrooertv rnas I S -1271. 4 S. D. 273. 183 N. W. 652. andMinnehahaeounty; thatthepropertywasl$ 4271,44 S. D.273, 183 N' W.652, and

destroyed by fire, and that thereafter I it also held that the objection to the

petitioner presented a false elaim to.its I failure to state the venue in the infor-'agents; the language of the inforrnation I mation was waived- by the failure to

H:lt, i, : S, r' i?! :"'i',',i:lrl it r B l, fl I i 3 ; LH; u ffiabout the ytn day oI January, J-vzu, tnc ooscrveo rna[ wtra[ appe[ee ls reatry

said defendant, George W. Egan. then' see-tin-5"un ttr@is--E--reviep-Tr

anal there did wilfullr', unlawfulll', and, h@iortf

feloniouslv present and eause to be'th

presentecl"to'F. C. IT'hitehouse & Com-1t a

pany, who were at that time aeting as p@{tnp;znd-affi

[he agents for the Firemen's Insurance decisibn of the state court, holding thqt'

Comp-anv of Newark, New Jersep', a i urrder the Rcvised Code of 1919 (S$

false and fraudulent claim and proof in1.1725, 4777, 4779), the appellee waived

support of sueh claim."

The eircuit court of l\{innehaha coun-

tv, in which appellee's trial and con-

viction wrere had, by the provisions of

the Constitution of South Dakota ($ 14,

art. 5) and the Reviseil Code of South

Daliota 1919, S 4653, is given original

jurisdiction of all actions and eauses,

09 IJ. cal.

the ob.iection that the information tlid

not state the venue bv not demurring,

was a denial of his constitutional rights

whith ean be reviewed on habeas corpus.

It is the settled rule of this court that | .7d

habeas corpus calls in guestion only the | /'

--t-

;urisaictioi of the .r;;a--;h"* jr[- | ni\.

ment is challenged. Andrews v. Sw.afiz. I 7*_.",l03e ' *'Z

- d .^2-r,\<-4't+'-2, l\*-'17. 1-. 1"ai 1,

\= 6_

,' r\ ]

-'

.\\

IF

G

.

'-- \io*o"J-u ]'";'

#ffi#ffffiffi*ff

fi ri*i ;il liil il ligI iE

lr

fi iiii|}lli i{ iii iilii

I igii|glf;l:tE

; E

*i i : : ; - s sir ; ! :i i i' E

' E

ru - i ci

ffi-t ;, ;- : ie ,

a ; l; *;

n - *; i, =

' =

, iiff ffifI ;S

iaiil i; i ii I i3ilfi i ii l i

ff ffiiii$i $l iffilii iiiilffiif

: il iH

iiff ii i #riiii: i i iiii

i *l?ilii I f i i iiiff iiiia *i il :tri ii:

s ? i i?i : l I iff I ii: ; ;1 i ii ii ii : ;iI.

i i:, iai: r=

:,

: s ;: i*,

=

r lif

i I I I ; i fi l! I i* ; i lii}ff if3iliI ifi ii

E

i i;

=

"? ,"-r-I

i 3-

*3;.

E

osN

=

;;H

dH

,E

8:.{ E

E

E

.E

E

g

inesogF

T

a(AaI,lFztrl

F

i

E

<

tE

r

UF

r

&p(-)

E

I

f.l

frEats.t.A