Carr v. Montgomery County Board of Education Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

April 17, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Carr v. Montgomery County Board of Education Brief for Appellants, 1970. d90898e2-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/549ad26d-d394-4272-83f6-0c6b7e4cd9d1/carr-v-montgomery-county-board-of-education-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

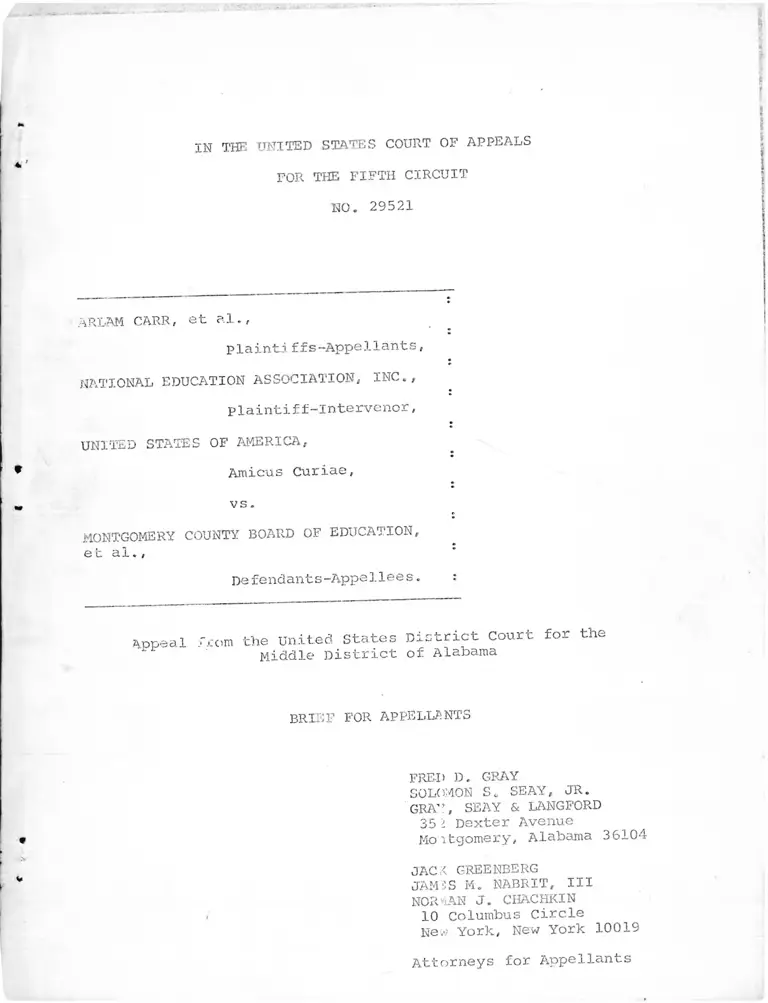

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO. 29521

ARLAM CARR, et al.,

plaintAffs-Appellants,

NATIONAL EDUCATION ASSOCIATION, INC.,

plainti f f-Inte rvenor,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Amicus Curiae,

vs.

MONTGOMERY COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

et al.,

Defendants-Appellees«,

Appeal rom the United States District Court for the

Middle District of Alabama

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

FRED D. GRAY

SOLOMON Sc SEAY, JR.

GRAY, SEAY & LANGFORD

35 > Dexter Avenue

Montgomery, Alabama 36104

JACcC GREENBERG

JAM5S M. NABRIT, III

NORTAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Table of Authorities ................

Issues Presented for Review..........

Statement

History of the Litigation . . . .

Results Under Freedom of Choice .

The H.E.W. Plan ................

The Board's Plan................

plaintiffs' Objections..........

Argument

The Board's Plan Fails to

Identifiable Schools and

Essential Characteristic

Eliminate Racially

Thus Retains the

of a Dual School System. . .

The Board's Decisions to Close McDavid Elementary,

Kale Elementary and Booker T. Washington High

School Retard Desegregation and Unfairly Place

the Burden of Desegregation Upon Black Students .

Conclusion

ii

1

2

5

5

8

11

12

31

38

l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Cases

Adams v. Mathews., 403 F.2d 181 (5th Cir. 1968) 13, 24

Bivins v. Board of Public Educ. of Bibb County,

284 F. Supp. 888 (M.D. Ga. 1967)................

Brewer v. School Bd. of City of Norfolk, 397 F.2d

37 (4th Cir. 1968)..............................

Brice v. Landis, Civ. No. 51805 (N.D. Cal.,

August 8, 1969) ................................

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 (E.D.S.C. 1955). .

Brooks v. County School Bd. of Arlington County,

324 F.2d 303 (4th Cir. 1963)....................

Brown v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954); 349 U.S.

294 (1955)......................................

31

21

34

24

24

24, 31

Carr

Carr

Carr

Carr

Carr

Carr

Cato

v. Montgomery County Bd. of Educ., 232 F. Supp.

705 (M.D. Ala. 1964)................................

v. Montgomery County Bd. of Educ., 11 Race Rel.

L. Rptr. 582 (M.D. Ala. 1965)......................

v. Montgomery County Bd. of Educ., 253 F. Supp.

306 (M.D. Ala. 1966)................* ..............

v. Montgomery County Bd. of Educ., 289 F. Supp.

647 (M.D. Ala. 1968)............ ....................

v. Montgomery County Bd. of Educ., 400 F.2d 1

(5th Cir. 1968) ....................................

v. Montgomery County Bd. of Educ., 402 F.2d

784 (5th Cir. 1968) ................................

v. Parham, 297 F. Supp. 403 (E.D. Ark. 1969)........

Cato v. Parham, Civ. No. PB-67-C-69 (E.D. Ark.,

July 25, 1969)....................................

Davis v. School Dist. of City of Pontiac, Civ. No. 32392

(E.D. Mich., February 17, 1970) ..................

Dove v. Parham, 282 F.2d 256 (8th Cir. 1960)

Dowell v. School Bd. of Oklahoma City,

(W.D. Okla. 1965), aff'd 375 F.2d

cert, denied, 389 U.S. 847 (1967)

244 F. Supp. 971

158 (10th Cir.),

20

21

24

31

Page

Dowell v. School Bd. of Oklahoma City, Civ. No. 9452

(W.D. Okla., August 8, 1969), aff'd 396 U.S.

296 (1969)......................................

Ellis v. Board of Public Instruction of Orange County,

No. 29124 (5th Cir., February 17, 1970) ........

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County, 391

U.S. 430 (1968) ................................

19

22, 23

4, 12, 23,

24, 27

Haney v. County Bd. of Educ. of Sevier County, 410

F. 2d 920 (8th Cir. 1969)......................

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Dist.. ,

409 F.2d 682 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 396 U.S.

940 (1969)....................................

Jackson v. Marvell School Dist. No. 22, 416 F.2d 380

(8th Cir. 1969) (en banc) (per curiam)..........

Jackson Municipal Separate School Dist. v. Evers, 357

F.2d 653 (5th Cir. 1966). ....................

Griffin v. County School Bd. of Prince Edward County,

377 U.S. 218 (1964) ..........................

Kemp v. Beasley, No. 19782 (8th Cir., March 17, 1970)

19

13, 19, 24

13

25

31

13, 18, 25,

29

Keyes v. School Dist. No.

279 (D. Colo.), stay

(Mr. Justice Brennan

1, Denver, 303 F. Supp.

vacated, 396 U.S. 1215 (1969)

in Chambers)..............

Lee v. Macon County Bd. of Educ., 267 F. Supp. 458

(M.D. Ala. 1967)............................

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965)..........

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964) ..............

Monroe v. Board of Comm'rs of Jackson, 391 U.S. 450 (1968)

Moore v. Tangipahoa Parish School Bd., 304 F. Supp.

244 (E.D. La. 1969) ................................

Northcross v. Hoard of Educ. of Memphis, 333 F.2d

661 (6th Cir. 1964) ................................

Quarles v. Oxford Municipal Separate School Dist.,

Civ. No. UC6962-K (N.D. Miss., January /, 1970) . . .

19, 28

4

23

36

4

28

26

35-2 6

i n

Page

Raney v. Board of Educ. of Gould, 391 U.S. 443 (1968).

Ross v. Dyer, 312 F.2d 191 (5th Cir. 1962) ..........

Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618 (1969) ............

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dist.,

419 F.2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1969) ..................

Spangler v. Pasadena City Bd. of Educ., Civ. No.

68-1438-R (C.D. Cal., March 12, 1970) ........ ■

Stell v. Savannah-Chatham Bd. of Educ., 318 F.2d 425

(5th Cir. 1963); 333 F.2d 55 (5th Cir. 1964); 387

F.2d 486 (5th Cir. 1967)........................

4, 25

24, 26

27

28

20

25

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 300 F.

Supp. 1358 (W.D.N.C. 1969)..........................

Turner v. Goolsby, 225 F. Supp. 724 (S.D. Ga. 1965). . .

United States v. Board of Trustees of Crosby Independent

School Dist., No. 29286 (5th Cir., April 6, 1970) . 28, 29

United States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School

Dist., 406 F.2d 1086 (5tn Cir, 1969). ........

United States v. Guest, 383 U.S. 745 (1966)..........

United States v. Indianola Municipal Separate School

Dist., 410 F.2d.626 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 396

U.S. 1011 (1969)................................

United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ., 372

F.2d 836 (1966), aff'd on rehearing en banc, 38U

F 2d 385 (5th Cir.), cert, denied sub norn. Caddo

Parish School Bd. v. United States, 389 U.S. 840

(1967).............................. ............

13, 19

22

12, 19, 25

3, 23, 24,

28

United States v, Montgomery County Bd. of Educ.,

395 U.S. 225 (1969) ......................

United States v. School Dist. 151, 286

(N.D. 111.), aff'd 404 F.2d 1125

F. Supp.

’7th Cir.

786

1968). .

Valley v. Rapides Parish School Bd., No. 2923/ (5th

Cir., Maich 6, 1970)........................

4

21, 28

19-20

Other Authorities

/

Weinberg, Race and Place

Neighborhood School

Catalogue No. FS 5.

— A Legal History of the

(U.S. Gov't Printing Office,

238:38005, 1967) .......... 25

3-V

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

NO„ 29521

ARLAM CARR, et al.,

plaintiffs-Appellants,

NATIONAL EDUCATION ASSOCIATION, INC.,

plainiiff-lnrervenor,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Amicus Curiae,

vs.

MONTGOMERY COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

et al.,

Defendants-Appcllees.

BRIEF FOR appell a nts

Issues presented for Review

1. Whether the plan approved belcw will eliminate the

Montgomery, Alabama dual school system "root and branch" by totally

disestablishing segregated pupil attendance patterns and

eliminating the racial identities of the Montgomery County public

schools.

2. Whether the Board of Education met its heavy burden

of justifying its decision to close otherwise satisfactory

schools rather than require white students to attend formerly

all-Negro facilities.

Statement

History of the Litigation

This school desegregation action was commenced May 11, 1964

on behalf of the class of Negro schoolchildren eligible to attend

the public schools of Montgomery, Alabama. On May 18, 1964, the

United States was formally designated amicus curiae by the district

court.17 Plaintiffs sought, and still seek, enforcement of their

constitutional right to attend public schools which are not

maintained on the basis of, or so as to perpetuate, racial

distinctions.

in its initial opinion granting a preliminary injunction, the

district court found the defendants to maintain "one set of schools

to be attended exclusively by Negro students and one set of schools

to be attended exclusively by white students" through various

devices, including pupil assignments through the use of attendance

areas' or 'district zones,' which areas are, according to the maps

introduced into evidence in this case, very obviously drawn on the

basis of race and color." 232 F. Supp. 705, 707 (M.D. Ala. 1964).

Accordingly, the district court required the school district to take

affirmative action to desegregate the schools other than mere

acknowledgement of the possibility that Negro students might apply

to transfer to white schools pursuant to the Alabama School Placement

1/

--- Thi ^ I i t H H T ^ J t T n t e r e d its order Pri^ t° ^he Passage

of the civil Rights Act of 1964, which permits h Un its.

States t.o bring or intervene m school desegregation i

2

Law. Id. at 709. For the 1964-65 school year, the court

specified certain public notice of transfer rights to be given,

and established a minimum period during which applications for

transfer from first, tenth, eleventh and twelfth grade students

would be accepted. Ibid. Subsequent orders entered by the

district court accelerated application of Alabama School Placement

Law provisions to the remaining grades, e.g_. , 11 Race Rel. L. Rptr

582 (1965), and later required mandatory choices, honored without

reference to the criteria of the state placement law, see 253 F.

Supp. 306 (19 66).

After the decision in United States v. j^fferson_County_^

o£ Educ , 372 F . 2d 836 (1966), afTd on rehearin£ en banc, 380 F.

2d 385 (5th Cir.) , cert, denied sub nortu Caddo,parish School_Bd^ v.

United States, 389 U.S. 840 (1967), the model free choice decree

was made applicable to Montgomery County. 12 Race Rel. L. Rptr. 1200

(1967). August 17, 1967 and February 7, 1968 motions for further

relief filed by the United States and joined in by the plaintiffs

resulted in further order of the district court, which recognized in

its opinion of March 2, 1968, 289 F. Supp. 647, that there was still

a dual school system in Montgomery County; the court warned:

Third, unless the 11 freedom-of-choice "

plan is more effectively and less dilatorily

used by the defendants in this case, this

Court will have no alternative except to

order some other plan used. 289 F. Supp. at

2/

653.

2/ The district court required further specific steps to

be taken by the Montgomery County Board of Education in

the following areas:

/

3

August 8, 1969, plaintiffs and the United States joined in

another motion for further relief seeking, in light of the Supreme

' Court decisions in Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430; Monroe v. Board of School Comm'rs of Jackson, 391

U.S. 450; and Raney v. Board of Educ. of Gould, 391 U.S. 443 (1968),

I the adoption and implementation of a desegregation plan other than

freedom of choice. On August 19, 1969 the district court requested

the Department of Health, Education and Welfare to file a proposed

2/ [continued]

construction[approval of State Superintendent of Education

to he obtained in accord with Lee, v. Macon County Bd. oJL

Educ.. 267 F. Supp. 458, 470-72, 480-81, before contracts

let] ;

transportation [bus routes to be redrawn on a non-

discriminatory basis; projected routes to be approved by

court];

supplementary efforts to encourage Negroes to attend

schools which the court found were deliberately located,

designed, constructed and operated to project a whit

image and to discourage Negro attendance; and

faculty desegregation [a specific minimum ratio of one

minority teacher for every six staff members in schools

with more than twelve teachers was required for ^ ^ - 6 9

with an ultimate goal stated of hiring and assigning teachers

so as to produce, at each school, the approximate racial

ratio among the faculty as existed m the entire system].

The school board appealed that, portion of the order

related to faculty, which was modified by a panel of this

Court so as to eliminate the requirement of ultimate ratio

assignment, 400 F.2d 1 (1968). shearing en banc was denied

by an evenly divided court, 402 F.2d 784 (1968) but on

June 2, 1969, the United States Supreme Court held that toe

district; judge had not abused his discretion in requiring such

assignments in order to disestablish the past pattern of

racially discriminatory faculty placement. United Stat_s .

Montgomery County Bd. of Educ., 395 U.S. 225 (19 9).

4

plan to disestablish the dual school system in Montgomery County,

and allowed the school board to propose its own plan if it so

desired. These plans were filed January 19, 1970 and February 6,

1970, respectively. plaintiffs filed objections to both plan-

February 19, 1970, amended February 24, 1970, which also incorporated

certain suggestions for further desegregation. After a hearing

February 24, the district court entered judgment approving, with

slight modifications, the plan submitted by the Montgomery County

Board of Education. Notice of appeal was filed by plaintiffs

March 12, 1970.

Results under Freedom of Choice

As noted above, the Montgomery County schools operated

pursuant to Jefferson-type freedom of choice during the school

years 1967-68, 1968-69 and 1969-70. Prior thereto, transfer plans

modeled upon the Alabama School Placement Law or upon the 1966

guidelines issued by the Department of Health, Education and

Welfare were utilized pursuant to the district court's orders.

As the court below recognized in its August 19, 1969 order

requiring submission of new plans, three years of free choice had

failed to eradicate the ingrained duality of the Montgomery County

school system. Of some 68 schools operated at all grade level^,

four enrolled only white students and 26 only black students. All

3/ The district court had required for 1969 70 that at

least 20Yo of all black students in the system be in

attendance at integrated schools the Board responded y

transporting Negro students from the area sur^°u™ ^ g g

Montgomery to previously all-white schools. In 1968-69

there were eight all-white and 27 all-black schools. Many

schools enrolled only one or two Negro pupils.

5 _

of the schools which had been all-black in 1964, prior to the

issuance of the first decree in this litigation, were still all

black. Many of the schools which had been all-white in 1964 were

still all-white. A handful of previously all-white schools now

had token integration, and a few enrolled.such substantial numbers

of Negro students that they seemed in danger of turning to all-black

4/schools.

The reasons for the failure of free choice are complex and

varied; there can be little doubt, however, that the refusal of

the defendants to even attempt to make it work contributed heavily

to the lack of results. The district court found in 1968, for

example, that the school board had deliberately ere:.ted new racially

identifiable white schools in white neighborhoods, had expanded

identifiable black schools in Negro neighborhoods to contain the

Negro school population, had retained a racially dual transportation

system, had intentionally avoided scheduling athletic content

between traditionally white and traditionally Negro schools, and

had failed to take advantage of the opportunities presented to

assign newly hired teachers to faculties where their race was in

the minority. 289 F. Supp. at 650-61. It is in the light of these

actions by which the board manifested its lack of real desire to

implement a unitary, nonracial school system, that the efficacy of

the plan it now proposes must be judged.

4/ As wearo students choose a previously white facility in

through ^ref chiice^r j h a ^ t h f f i

S i s anyVmystery In his February 24 1968 opinion,

“ S E n S E a“ a f m a ^ t t e L ^ s e g ^ t i o n unlikely: See. 289

F. Supp. at 651. _ 6 _

The H.E.W. Plan

The plan drawn by the Office of Education proposed to

reorganize the Montgomery County school system by (a) drawing

zone lines around each school facility; (b) transporting students

from the county area immediately adjacent.to the City of

Montgomery to schools in which their race would be in a minority;

and (c) pairing or clustering several city schools where application

of the first two methods had resulted in either all-black or

overwhelmingly black schools in this 56%-white school system.

The H.E.W. plan also recommended closing several facilities,

including Booker T. Washington Senior High School in Montgomery,

and grade restructuring at several rural facilities.

The H.E.W. plan noted that "the main challenge the school

district faces. . . is the disestablishment of the twenty-three

schools that remain with all-Negro student enrollments. ’The

removal of the. racial identity of schools within a district is

one of the major steps toward providing, equal educational

opportunities for all of its sfaidents. . . . " (p- 4> (emphasis

supplied).

Simple zoning would not achieve the desired result, according

to H.E.W.:

It will be noted that, in addition to the

three all-Negro city schools, twelve of the

converted all-Negro city schools would have

white enrollments under 13%, and as low as

4%. With such percentages, there is a f—

question as to their continuing as identifiable

integrated schools.

_ 7 -

Alternative suggestions will be made that will

both provide integrated education in all of the

district's schools and in substantial numbers

as to provide a stable pattern of integrated

education. (p. 11) (emphasis supplied)

Even its own recommended plan contained flaws, H.E.W.

said:

Under the zone and pairing plan herein submitted,

there will be schools with critical minority

group enrollments. The school district

officials should be mindful of the need to

improve these racial ratios and offset the

probability of these schools reverting to one-

race facilities. . . .The selection of sites

for new schools should be made with maximum

consideration toward providing an integrated

education for the students who are to attend.

(p. 22) .

Nevertheless, the Board refused to accept even the limited plan

proposed by H.E.W.

The Board's Plan

The Board willingly adopted the portions of the H.E.W. plan

which referred to attendance zoning, and further acceded to some

suggestions made by H.E.W. concerning the restructuring of grade

levels in rural schools located in the southern part of Montgomery

County. The Board also suggested certain deviations from the

precise zone lines recommended by H.E.W., mainly to simplify

transportation routing (Board's Plan, pp. 3-6). It strongly

disagreed with the remaining H.E.W. recommedations, however.

Whereas H.E.W. had recommended rerouting to the all-black

Loveless Jr. High School some of the white students now being

> 8

transported from rural areas into the Baldwin Jr. High School, the

Board proposed to explicitly limit transportation of "all children

who live in a ncn-zoned [rural] area to previously white schools,"

although it recognized that this would desegregate only previou y

white schools where sound city zoning would not accomplish this"

(p. 2) (emphasis supplied).

The Board opposed the idea of pairing any schools; rather than

do so, it was prepared to close entirely the all-Negro Hale

Elementary School (paired with Highland Gardens Elementary under

the H.E.W. plan), the all-Hegro McDavid Elementary School (paired

with Forest Avenue Elementary under the H.E.W. plan), and the all-

Negro Booker T. Washington High School (into which a minority of

white students could be zoned).

The Board also declined to endorse H.E.W. recommendations to

pair Capitol Heights (white) and Paterson (Negro) elementanes;

Fews (Negro), Goode street (Negro) and Bellinger Hill (white)

elementaries; and to close Chilton Elementary and reassign its

students to Loveless.

As expressed in its plan and in the testimony of the

Superintendent, pairing was not favored because (1) it violated

the concept of assignment to the nearest school (Tr. 17, 27, 33,

35, 37, 38); (2) it increased the distances which children would

be required tc walk to their assigned schools (Tr. 18, 25-27, 23,

33, 35-36, 37, 38); (3) it would split community and parental

support which was essential to provide supplementary materials and

5/ References are to the transcript of the hearing held

February 24, 1970.

_ 9 _

facilities at each school (Tr. 18, 27, 33, 35, 37, 38), (4) it

would split families, with children attending different schools

where they now attend the same school (Tr. 18, 25, 27, 33, 35,

37, 38); (5) it would make recruitment of children for Safety

patrols difficult since some schools would have grades too low

for such duties (Tr. 18); (6) it deprived teachers of the super

visory assistance of older children on the playground (Tr. 19);

(7) where capacities of paired schools were not equal, splitting

of grades into sections would seem to be required (Tr. 19, 27, 33,

37/ 38); and finally, (8) pairing would often place whites in a

greater minority than they were before (Tr. 20-21, 26). The same

reasons were advanced for opposing H.E.W.’s -proposals regarding

Baldwin, Chilton and Loveless (Tr. 29-31).

On the other hand, H.E.W. Program Officer Miller, who was

part of the team which developed the Montgomery County plan

(Tr. 112) (and who had substantial teaching and administrative

experience, Tr. 110), testified that pairing is a sound educational

technique with numerous benefits, and it is particularly useful as

a tool to disestablish the dual school system (Tr. 119). Miller

testified that pairing would not adversely affect the district's

6-3-3 grade structure (Tr. 126-27) nor require children to walk

past one school offering the same grades as the school to which

they were assigned (Tr. 129); that student safety patrols could be

provided in the entire paired school area by recruiting students in

the upper grades (Tr. 144); that the importance of all the children

in a family attending the same school facility varied with each

> »

10

family; and that the “nearest school assignment" concept was

relatively new, having been embraced by school boards only after

the courts began to require integration (Tr. 149-51).

Plaintiffs' Objections

Plaintiffs objected to both the H.E.W. and Board of Education

plans as insufficient to establish a unitary school system, and

objected also to closing satisfactory but traditionally all-black

schools rather than assigning white students to them. plaintiff-

suggested greater use of the pairing device to remove the racial

identiflability of schools which would be perpetuated by the H.E.W

6/

and Board plans.

Plaintiffs supported the H.E.W. proposals to pair McDavrd and

Forest Avenue Elementary Schools, three blocks apart, rather than

close McDavid and send additional black students to Booker T.

Washington (Tr. 22). McDavid was constructed at the same^time as

an addition was built at Forest Avenue (Tr. 60, 120-21). Plaintiffs

r- / Plaintiffs suggested the possitle pairing of Booker T.

and/or a n d ^ a^Ce^rgia

Washington Junior High Schools.

7/ Plaintiffs also sought to require the Board to adopt the

“ -recommended pairing of Hale and Highland gardens.Whil^* cor ceding that Hale would^eventually^have^to^be^closed^

utilized^until IS addition to Highland Gardens which could^

the°BoarcVs p ^ ^ o s ^ g ^ “^ “ “nSnSditiinal Wegrc ~

students to Paterson (Tr. 30).

_ 11

opposed the reassignment o£ Booker T. Washington High School

students to overcrowded schools (Tr. 79) instead of bringing white

students into the school (see Tr. 77).

The district court found that the Board's plan would achieve

"[cjomplete disestablishment of the dual school system to the

extent that it is based upon race. . and rejected plaintiffs'

objections as "based upon a theory that racial balance and/or

student ratios as opposed to complete disestablishment of a dual

school system is required by the law. . . . While pairing of

schools may sometimes be required to disestablish a dual system,

the pairing of schools or the busing of students to achieve a racial

balance, or to achieve a certain ratio of black and white students

in a school is not required by the law.”

ARGUMENT

The Board's Plan Fails to Elxmxnate

Racially Identifiable Schools and

Thus Retains the Esseixtial

Characteristic of a Dual School System

in Green v. County School Bd. of Ne^KentOauntfr 391 U.S.

430, 438, 442 (1968), the Supreme Court held it the affirmative

obligation of school boards to eliminate the dual biracial system

of public education “root and branch” and establish "a system

without a 'white' school and a 'Negro' school, but just schools."

This Court explicated the same Constitutional standard in United

States v. Tnc ianola Municipal separate School Dist ,̂ 410 F.2d 626,

631 (5th cir. 1969) in referring to “a unitary school system with

both substantially desearegated student bodies and teaching staffs."

_ 12

(emphasis supplied). Accord, Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal

o perate School Dist.f 409 F.2d 682 (5th Cir.), cert, denied,

396 U.S. 940 (1969); TTnited States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate

School Dist., 406 F.2d 1086 (5th Cir. 1969); Kemy v. Beasley,,- 8/

No. 19,782 (8th Cir., March 17, 1970).

Judged by these standards, the plan approved below will

not create a unitary school system in Montgomery County, Alabama.

Although the geographic zones proposed by the Board will result in

some mixed racial attendance at every school facility which is to

be operated with the exception of all-black Loveless Elementary

School, it seems clear that the system as a whole has undergone no

substantial change. The plan will not shake loose the racial

identities which defendants have over the years affixed to the

schools. Those schools which have remained all-black during the

past three years of operation under freedom-of-choice will have a

distinctively and consistently higher black enrollment in the

coming year than ohter schools in the system. Similarly, the

traditional white schools remain sharply distinguishable because

of their relatively lower black enrollments. Table 1 indicates

the past and projected Negro enrollments at each school to be

operated next year under the Board's plan.

§/ We but state the obvious fact that schools may remain

racially identifiable even though they are ionger 10°/„

black or 100% white, cf. Adams v. Math£_ys* 403 F.2d 181

(5 th 'cir. 1968). The Eighth Circuit has noted, for examp ,

that "[t]he admittance of 36 white students into a ormei .y

all-Negro school still attended by 660 Negroes cannot be

sa"id to have the effect of « n | ^ f £ ^ h | j c h j o y r

" M 380 384 •(8th^CirhT96< , ) T i O S S r(HI 1S±II> •

_ 13

: it* •> JUA V.( •- V.. ur .-

TABLE 1

% Negro Enrollment

il

School 19 67-68 1968-69 1969-70 1970-71

Elementary:

Bear 0.0 0.0 0.0 7.4

Bellinger Hill 0.0 1.7 12.4 50.5

Bellingrath 4.7 6.8 8.3 5.9

Bellingslea 100.0 100.0 100.0 93.4

j

Booher T. Washington 100.0 100.0 100.0 91.4

Capitol Heights 8.9 14.9 22.0 33.0

Carver 100.0 100.0 100.0 89.7

Catoma 0.0 0.0t 1.5 40.7

Chilton 1.9 14.4 30.2 75.2

Chisholm 0.2 0.3 1.3 24.1

Crump — 11.1 16.7 18.1

Daisy Lawrence 100.0 100.0 100.0 94.8

Dalraida 0.0 0.2 0.2 10.9

Dannelly 0.0 0.9 0.8 10.5

Davis 0.0 0.1 1.0 7.4

Dunbar 100.0 100.0 100.0 73.8

Fews 100.0 100.0 100.0 96.0

Flowers 0.0 0.0 0.0 17.6

Floyd 0.0 0.2 2.3 15.3

Forest Avenue 1.3 4.3 4.1 31.2

Georgia Washington 100.0 . 100.0 100.0 90.1

Goode Street 43.4 100.0 100.0 94.7

iHarrison 21.1 19.2 18.1 13.2

Hayneville 100.0 100.0 100.0 79.3

14

School 1967-68 1968-69 1969-70 1970-71

Elementary; (continued)

Head

Highland Avenue

Highland Gardens

Johnson

Loveless

McIntyre

MacMillan

Madison park

Morningview

Paterson

pendar Street

pine Level

pintlala

Southlawn

1.3 1.6

0.4 0.6

5.1 9.0

0.6 s 0.0

100.0 100.0

100.0 100.0

0.0 12.9

100.0 100.0

o • o 1.3

100.0 100.0

0.4 5.0

o•o 4.9

0.7 16.5

3.0

2.2 17.5

0.7 16.4

11.1 43.4

0.0 0.0

100.0 100.0

100.0 88.5

23.3 61.3

100.0 84.1

2.0 16.6

100.0 93.4

10.1 27.8

20.3 56.5

22.6 64.0

8.5 22.8

Junior High Schools:

Baldwin

Bellingrath

Booker T. Washington

Capitol Heights

Carver

Cloverdale

Floyd

Georgia Washington

Goodwyn

i

1.7 2.2 3.1 33.4

3.1 6.3 13.5 19.2

100.0 100.0 100.0 91.0

1.0 1.7 2.9 17.9

100.0 100.0 100.0 96.0

1.0 1.2 1.4 15.7

0.0 0.0 0.0 18.9

100.0 100.0 100.0 84.1

10.0 6.4 5.2 14.6

15 _

School 1967-68 1968-69 1969-70 1970-71

Junior Hiqh Schools: (continued)

Hayneville 100.0 100.0 100.0 78.6

Houston Hill — 100 ; 0 100.0 84.1

Loveless ' 100.0 100.0 100.0 96.8

McIntyre 100.0 100.0 100.0 91.9

Montgomery County 0.8 1.6 7.8 62.9

Hiqh Schools:

Carver 100.0 100.0 100.0 72.4

Jeff Davis — 12.5 5.6 28.2

3 9 5.9 9.6 30.9Lanier

0.9 0.8 1.7 25.3Lee

Montgomery County 1.6 2.7 5.5 59.9

(Source: Jefferson reports filed with the district court June 7,

1967; September 16, 19 68; June 6, 19 69; district court1s order of

February 25, 1970).

The fact of continued racial identifiability is shown

graphically on the following page, using the junior high schools

as an example.. (The pattern is the same for elementary schools

but we have not prepared a chart because of the complexity caused

by the greater number of schools it is obvious in the high schools

from Table 1, above).

\

- 10

sn

oo

-W

^S

^

*■" /* _ . . IV/.IVyUUUW \ IV

C\-c\i£fsOftv.€.

C.ftPVTOL. VVe\<3-ViT5 ■

FUOXI5 •

■&£LU£6̂ P\Trt-

— * *

HM̂ evivuv.6 ■

\-k)OSTotO \V ( L.U. .

T3ooK&£~T, U)fVScVlf̂ -Tcrl

fAc-X̂ TSRe

l_0\j 6LE-SS ■

6/o USG-PsO ^TOD&^T £MR0WUWE^T

The chart makes evident that the traditionally white schools

remain clustered at the bottom of the scale; all have less than

20% black enrollment with the exception of Baldwin, which will

be one-third Negro under the Board's plan. In contrast, none of

the former all-black junior high schools in this 56%-white system

has a black enrollment less than 78.6%. To the Negro parent or

child looking at the Montgomery County school system, little if

9/

anything has changed.

The district court erred in concluding that “ [p) lamtiffs'

objections. . . appear to be based upon a theory that racial

balance and/or student ratios as opposed to the complete disestablish

ment of a dual school system is required by the law." plaintiffs

did not seek and do not here urge that every school have a 44%-black

enrollment. What plaintiffs are entitled to is the disestablishment

of student assignment patterns which consistently retain the racial

identities of the Montgomery County public schools.

9/

10/

If one considers racially identifiable those schools with

less than a 15% minority enrollment for purposes ° L 22% cf '

then 47% of the black junior high school students and 22% of

the white junior high school students will / ^ e n d r.aoi y _

identifiable Negro and white schools, respectively, during

It 10-71. Applying this criterion to the entire system, 43/>

of the black students and 22% of the white students at all

grade levels will be assigned to such racially identifi

facilities.

we are in complete accord with the recent f R a t i o n of

p e r c L S ^ - r ^ s S o o f j o ^ a n l J e r e

even one school might have a black majority an unemotionally

considered^^ h e ”1 syste^is^unitissd^ within the" Supreme Court‘d

Alexander requirement." Kemp v. Beasley, supra, slip op

pp” 14-16. The fatal defect of Montgomery County s P

S a t perfect racial balance is not achieved at every school, but

tl>at the racial identity of no school is eliminated.

- 18

Defendants argue that they have applied an objective standard

in the drawing of zones, and that they are thus relieved of

responsibility for the resulting continued segregated pattern of

attendance. We see no validity in such an argument.

In the first place, the Board adopted this "objective

standard" with full knowledge that it would not meet its affirmative

Constitutional responsibilities by so doing. It was aware that

neighborhoods are custom-segregated (cf.. Henry, v. Clarksdale

Municipal Separate School Dist^ supra) in Montgomery (Tr. 54) but

it made no effort to overcome this pattern (Tr. 54-55). It knew

the natural effect of the kind of zoning it proposed was to

produce heavily black and heavily white schools (Tr. 46-47). The

school district may not permissibly continue its past discriminatory

assignment policies by the present application of neutral standards

which do not achieve the result of dismantling the dual system.

This is true whether the method used is free choice or geographic

zoning. Otherwise "the equal protection clause would have little-

meaning. Such a position 'would allow a state to evade its

constitutional responsibility by carve-outs of small units."'

Haney v. county Bd. of Educ. of Sevier County, 410 F.2d 920, 9zi

(8th Cir. 1969). See Dowell v. School Bd. of Oklahoma City, Civ.

No. 9452 (W.D. Okla., Aug. 8, 1969), affhi 396 U.S. 296 (1969);

Keyes v. School Dist. No. _U_jenyer, 303 F.Supp. 279, 289 (D. Colo.),

stay vacated, 396 U.S. 1215 (1969) (Mr. Justice Brennan, in Chambers)

Henry v. clarksdale Municipal Sepa_ra^_S^Ql_Pigt^/ * a-; — ̂

States v. Greenwood Municipal Separate School_Dist_._, supra; UnjLted

States v. Tndlanola Municipal SeparateySchool_DistiJ supra; Valley

19 _

V. Pap-ides parish School Bd.f No. 29237 (5th Cir., March 6, 1970);

Cato v. Parham, 297 F. Supp. 403, 409-10 (E.D. Ark. 1969); Cato v.

Parham, Civ. No,. PB-67-C-69 (E.D. Ark., July 25, 1969); Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ., 300 F. Supp. 1358 (W.D.N.C.

1969); Spangler v. Pasadena City Bd. of Educ^, Civ. No. 68-1438-R

(C.D. Cal., March 12, 1970).

Furthermore, it is established in this case that the school

board is directly responsible for its present inability to

substantially desegregate the schools by simple zoning. The

district court wrote in 1968:

The evidence further reflects that the

defendants have continued to construct

new schools and. expand some existing

schools; certainly, there is nothing

wrong with this except that the construction

of the new schools with proposed limited

capacities geared to the estimated white

community needs and located in predominantly

white neighborhoods and the expansion o~ the

existing schools located in predominantly ^

Negro neighborhoods violates both the spirit

and the letter of the desegregation plan for

the Montgomery County School System. Examples

of this are the construction of the Jefferson

Davis High School, the peter Crump Elementary

School and the Southlawn Elementary School

all in predominantly white neighborhoods --

and the expansion of Hayneville Road Schoo

and the Carver High School, both in predominantly

Negro neighborhoods. The location of these

schools and their proposed capacities cause the

effect"of this construction and the expansion to.

perpetuate'the dual school system based on race

Tn the Montgomery County School System. 289 F.

Supp7~at 651 (ernphasis supplied) .

Similar instances are revealed in the record. For example, McDavid

Elementary School, an all-Negro school, was constructed only three

blocks from Forest Avenue Elementary at the same time that an

addition to the latter was built with sufficient capacity to house

white students in the area (Tr. 60). The influence of such school

_ 20

construction upon neighborhood patterns is not to be disparaged.

■■Putting a school in a particular locution is the active force

which creates a temporary co-unity of interest among those who

at the moment have children in that school." Swann v. Ch^lotte^

^ 1P.nh,„c Bd. of Educe., SSES, 300 F- SUPP- 3t 13M (em£>haSiS

omitted). It is the school district's responsibility now to

disestablish what it has created. See United,States v. School

nlst, 151, 286 F. supp. 786. 799 (N.D. 111.). 404 1125

"(7th Cir. 19 68) ; Brewer v. s c h o o l ^ J l J ^ ^ 397 F.2d

37 (4th Cir. 1968) .

When the power to act is available, failure

to take the necessary steps so as to negat

nr alleviate a situation which xs harmful

fs as «ong as is the taking of affrrmatrve

steps to advance that situation.

~sKli'Kffi SHs'Sis-..

For a school Board to acquiesce in a housing

? S ^ ? t y nf o f S e rS v : n t ^ : e ^ e S ^ d a|arac-

^ o ^ C f f o r ^ l o S rSoCab?Sg;tena S eignore

S l o w e r ! control and responsibility h Board

c ^ 1 L o r S n d ^ b l i ^ l y 9

announce that for a Negro ^ “^ ^ “mSs^do isattendance at a ^ s c h o o l ^ l l ^ e mast_ ^

SFuiiet'f'aduS iEif!;°wUhbliisaprejudices and

opposition to integrated housing.

Davis v. School Dist. of Cia_gllS£li^' Clv' K°' 32392 <E'D'

February 17, 1970)(slip opinion at pF■ 13-14>'

‘.U jTr. J ' 'M ■ • * ' - -' - *•1L -V C-»v

Finally, the Board may not justify its failure to dismantle

the dual system by reference to any "nearest school assignment" or

••neighborhood school" concept.^ "Standards of placement cannot be

devised or given application to preserve an existing system of

11/ We submit that the recent decision of a panel of this

court in Ellis v. Board of Public Instruction of Orange

county n!t% 1 24 '(5th Cir.. Feb. 17, 19 ToT. is not controlling

fn^the" circumstances of this case. First, Ellis purported to

permit detention of a number of all-white and all-black schools

upon the explicit finding that the racial composition of such

schools resulted from "residential patterns." While the schoo

district may make such a claim here, the evidence and prior

findings in this case refute it, showingclear^ theresidential patterns in Montgomery have developed with the

encouragement and facilitation of defendants racially

qeareaated public schools. And while residential patterns

might also be the result in part of private discriminatory or

non-discriminatory action, the Board would still not be

of its dutv "[T]he involvement of the State need [not] be

exclusive or direct. In a variety of situations the Court has

found"state action of a nature sufficient to create rights

under the Equal protection Clause even though the participate

of the State was peripheral or its action was only .

severa/co-operative forces leading to the constitutional

violation." united States v. Guest, 383 U.S. 74b, /bb dp ,

Second, the neighborhood school system defined in was

one in which school attendance was based solely on h_1d

distance" assignment and school capacities. The court held

that " r i a n c e s V arbitrary cone lines or for reasons of

traffic, while reasonable on their face, might destroy the

integrity and the stability of tie entire assignment^lan.

Hence if Orange County, the school sys-tem domaintain a neighborhood assignment plan, it would have to^do

so without such variances (slip opinion at p. 1C) . Y -

Superintendent1s own admission, other factors such as more

c X e n i e n f transportation routings - r e considered rn drawrng

zone lir.es in Montgomery. More important, large \\

students are not assigned on the basis of zones at all,

blach'

I m / s ^ f f i ^ l / t ^ S t ^ § 5 ^ i h . ° L S l £ £ > d not preclude

the employment of differing assignment methods m other sc o

districts to bring about unitary school systems.

22

11/ (continued)

Finally, should the Court consider Ellis, applicable to

the facts of this case, we submit that ^ was n̂rong y

^ S L S S i l h every^vestig/of school^segregation as

yequireS by Gre|n v.

affirmative actioHTS? full desegregation would brush aside

the holding of Jefferson I:

the only adequate redress for, a

Previously overt system-wide policy or

seqreqatlon directed against Negroes a_s_

a c o llictive~entity is a system-wide

policy of integration.

united States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Edpcĵ ,

«Ta— (9th Cir ) aff'd on rehearing en b̂ nc./ 380 F.2d

385’ (1966) , cert. denlidTub-nonu Caddo parish School Bo.grd

^ united StatesT 389UhsT840 (1967) (emphasis in original) .

That command and remedy — to undo the effects of the

past - was not lightly arrived at by the jeff||s|n court

nor by the Green court. The point -ho'discriminatedprotection clause does not enjoin those who discriminate

in the nast (through school site selection, state encour g

■ c . m-mjated housing segregation and compulsory racial

ichSoJ segregation)* to^undo the effects of such discrimination,

then the light assured black children rests on quicksand,

in Louisiana v. united States, 380 US. 145, 154, (196.),

cited by the Green court, it was held:

the court has not merely the power

but the duty to render a decree which

will so far as possible eliminate the

discriminatory effects of the past as well

as bar like discrimination m the future.

"Residential patterns" do not lessen the school district's burden t^desegregate its schools, for the Green court said,

391 U.S. at 442 n. 6 (emphasis supplied):

in view of the situation found in New

Kent County, where there is. no reside n^il

seqreqatlon, the elimination of the dual

icfel ^ t e m and the establishment of a

‘unitary non-racial system could - ̂

readily achieved. . . by means of geographic

zoning. . . .

23

imposed segregation. Nor can educational principles and theories

serve to justify such a result." Dove v. Parham, 282 F.2d 256, 258

(8th Cir. I9 60);' accord, Ross v. Dyer, 312 F. 2d 191, 196 (5th Cn .

1962); Brooks v. County School Bd, of Arlington County, 324 F.2d

11/ (continued)

Ellis construed broadly tacitly overrules.Jefferson,

Adams v." Mathews, supra, Henry v. Clarksdafe, supra and

their progeny^ it spas the strength from Green and

resurrects the Briggs dictum; Ellis does to Jefferson an

Green what Briggs did to Brown: after ̂a system-wid^^

policy of segregation, neutrality on the part of school

officials will again satisfy the equal protection clause

If after sixteen years of protracted litigation the ®3ual

protection clause designates the segregated housing pattern

and school district policies of discriminatory si

selection as the final arbiter of pupil assignment, it has

played a cruel joke upon the black school children of this

Nation.

Ellis will not end school desegregation litigation.

Rather it will begin a new era marked by new kinds of proof

and more complex trial records. An equi-distance zoning

plan for other districts will result m numerous hearings

to determine whether the school district s policies on

school construction and site selection have been racial!

discriminatory. Those findings have already been made i

i-his case A similar attack against municipal authorities

will also develop to demonstrate that zoning ordinances and

other city policies have been and are designed to insure

that blacks and whites live in separate communities

It is too late in the day for defendants to claim that

current^residential patterns were not affected by segregated

schools. The only effective remedy is to destroy the

incentive to move to a particular area of the city where

hSSini patterns make it doubtful that school desegregation

will take place under zoning by substantially desegregating

the system.

2A

303, 308 (4th Clr. 1963); cf. Municipal Separate School

nist, V. Evers. 357 F.2d 653 (5th Clr. 1966); Shell v. Savannah-

Bd. of E d u c . 318 F.2d 425 (5th Clr. 1963), 333 F.2d 55

(5th Cir. 1964), 387 F. 2d 486 (5th Cir. 1967).

As Mr. Miller testified at the hearing below, the so-called

neighborhood school concept is a recent invention of school

districts which were more than willing to pay it no heed in the

past in order to maintain segregation. There is reason to believe

it has been honored more in the breach than in performance.

Weinberg, Face and Place - A

School (D.S. Gov't Printing office, Catalogue No. FS 5.238:38005, 196/).

The district court should have required the school distract to

implement the school pairings recommended by H.E.W. as well as

those suggested by plaintiffs in order to increase desegregation.

Pairing has received repeated judicial approval. Raney v. Board

of Educ. of Gould, supra, 391 D.S. at 448 n. 2; KemE_v. Beasley

surpa; united States v. indiauKdi^^

supra, 410 F.2d at 630. The purported objections to the procedure

raised by defendants range from the frivolous to the legally

insufficient.

The Board argues that pairing ought not be required because

it does not accord with the neighborhood school assignment concept

which the district now wishes to pursue. "When racial segregation

was required by law, nobody evoked the neighborhood school theory

to permit black children to attend white schools close to where

they lived. . . . The neighborhood school theory has no standing

to override ' the Constitution." Swann v. c h ^ p t l o t ^ c j e l * ! ^

25

of Educ., supra, 300 F. Supp. at 1369 (emphasis in original).

Second, pairing will increase the distances which children

will have to walk to school. But

Where the Board is under a compulsion

to desegregate the schools (1st Brown

case, 347 U.S. 483) we do not think

that drawing zone lines in such a

manner as to disturb the people as

little as possible is a proper factor

in rezoning the schools.

Northcross v. Board of Educ^ of Memphi^, 333 F.2d 661, 664 (6th

Cir. 1964).

Third, parental support will drop off and the schools will

lose supplemental materials and facilities furnished by P.T.A.

groups. There is no reason whatsoever to believe that parents who

are interested in the education of their children will not continue

to support the schools they are attending.

Fourth, the district objects to pairing because it would split

families, resulting in brothers and sisters going to different

schools. Such a justification for the ■'brother-sister" rule has

been explicitly rejected by this Court. Ross v. Dyer, 312 F.2d 191

(5th Cir. 1962).

Fifth, establishing Safety patrols would be rendered more

difficult. Again, there is no reason to believe that older youngsters

living in the part of the paired school area in which the lower

grade school was located could not serve as crossing guards near

their homes and then go on to school themselves.

/ 26

i i. ;;v • :aaieSK5WMW^-“

Sixth, teacners would be deprived of the supervisory

assistance of older children on the playgrounds. This hardly

seems worthy of comment, but we would note with regard to all

such arguments that the Supreme Court has held that a State may

not justify denail of equal protection rights for the sake of

limiting expenditures. Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U.S. 618, 633

(1969) .

Seventh, it school capacities were not equal, grades might

have to be split. Nothing in the H.E.W. plan suggests that this

would happen, nor are appellants aware of the exact harm involved

in having more than one section of a grade, as is the case at the

present time.

Finally, we think the record clearly reveals that the m a m

ground for the Board's opposition to pairing is that it would

place white children in a substantial minority m several of the

schools. This of course is a totally impermissible criterion.

Thus, we conclude that the school district has raised no

valid objections to the pairings suggested either by H.E.W. or by

the plaintiffs. But the district court was obligated to go further,

and to examine all alternative remedies which might be open to

disestablish the dual system. Green v. County Schoql_Bd^of_NgH.

Kent County, supra.

The district court would not consider, for example, plaintiffs'

suggested pairing of Goodwyn and Georgia Washington Junior High

schools, because transportation of pupils between ten and fourteen

- 27 -

• t ^ /m-v- a o\ vp +■ existincf bus 3rout3s servingmiles would be involved (Tr. 42). Yet existing

Georgia Washington carry up to 891 students (of its 1,221 students]

on rides averaging 20.6 miles one way, and existing bus routes

serving Goodwyn carry up to 291 students [of its 1,316 students]

on rides averaging 18.2 miles one way. (H.E.wJ Plan, pp. 23,25).

Obviously, provision of pupil transportation is nothing new in this

school district; the district court found in 1968 that defendants

had maintained a biracial transportation system to perpetuate

racial discrimination for a considerable length of time after the

entry of a decree enjoining such practices.

This Court has recently held that bus transportation is but

one factor to be weighed along with all the.other facilities of a

district in determining how the resources o^a school district may

best be used to dismantle the dual system. united states; v.

in the H.E.W. Plan showing the number of s

transported to each school.

, o/ Tn tlv s regard we note that the limitation on the court's

^ iurisdictionlSt forth in Section 407(a)(2) of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, « U.S C §2000c-6^a)(2) has^no^ ^

-gregation. U n i t e d ^

v . ^ , 3 / F ^ t T l 3 0 ;united States v. Schooj^ist^lbi., -a.£5 244,

Moore v. Tangipahoa parish Schoo.. Bd̂ _, * *nPnver

^ R e . ? y - 8i g f )l t ^ l 9 8 g 5 rTOiSa-sSie'B,̂ - ^ ° £

Independent School, Dist^, SBffik- . «*e_.

i H i t - e^licitl]; «eco|nIi5s-th,.; court s po«r to

compliance with constitutional s.andards see-tn i

" K “ £ t “

(reported at 419 F.2d 1211)-

28

i ^ r d of Trustees of Crosby independent School Di.st̂ ., No. 29,286

(5th Cir., April 6, 1970).

As the Eighth Circuit has recently put it:

We do not rule that busing is a constitutional

imperative. Busing is only one possible tool

in the implementation of unitary schools.

Busing may or may not be a useful factor in the

required and forthcoming solution of the elementary

school problem which the District faces It may

or may not be feasible to use it, m whole or in

part for Fairview-Watson-Murmil Heights and it

may or may not be feasible to use it, in whole

or in part, elsewhere in the system. Busing is

not an untried or new device for this District.

It has been used in the past and it is being used

fn an extent at the present.

Kemp v. Beasley, supra, slip opinion at p . 14.

During 1969-70, some 7,004 or 18% of all Montgomery County

students were bused by the school district an average of 18.7 miles

one way. Rearranging the present transportation routes offers hope

of increasing desegregation, as by transporting rural white students

to black schools in Montgomery, rather than to predominantly white

schools in accord with the Board's plan, but it seems obvious that

additional transportation of some, probably not a great many,

students will be necessary in order to substantially desegregate

the system. There is plainly no valid objection to busing that it

is used to promote integration, for this is the Constitutional

imperative. The board has no satisfactory theory to differentiate

that busing which is admittedly necessary from that which it finds

objectionable, i.e., to legally differentiate between "good" and

"bad" busing.

The Board attacks arrangements which involve transporting

children from their zone of residence to a non-adjacent zone,

29

although Superintendent McKee implicitly admitted that the entire

system could be desegregated through the use of non-contiguous

zones (Tr. 90). Pupils have no inherent right to attend any

particular school because of their place or residence. A child's

"own neighborhood school zone" does not exist in the order of

natural phenomena. It is the product of school board decision,

i.e., state action. Attendance areas and the grades served by

particular buildings are alsways subject to change and often are

changed. There is no good reason not to use available transportation

facilities to desegregate the schools, or to limit that transportation

to an artificial "adjacent" zone. Segregated schools need not

inevitably follow segregated housing patterns. There is nothing

inexorable about such segregation; there is merely the appearance

of inevitability. In sum, the only reason not to use buses to

integrate the schools is to keep them segregated.

Since the plan approved below fails to create a unitary school

system in Montgomery County, Alabama because it maintains the old

racial identities of the "black" and "white" schools without

achieving substantial desegregation, this cause should be remanded

to the district court for a thorough evaluation by the court of all

possible methods and devices to achieve such substantial desegragation

including but not limited to, pairing, contiguous and non-contiguous

zoning, rearrangement of existing transportation routes and prevision

of new routes, keeping some or all of the schools to be closed under

i 30

the Board's plan open to facilitate desegregation, etc.

14/

II

The Board's Decisions to Close

MeDavid Elementary, Hale

Elementary and Booker T. 'Washington

High School Retard Desegregation

and Unfairly Place the Burden of

Desegregation Upon Black Students

The decision of the Board to close certain facilites which

are being operated during 1969-70 accomplished two things: white

students were protected from additional travel and from being

placed in a minority, or greater minority position, and black

students were made to bear the brunt of integration.

14/ The district court's inquiry should be as broad as the

scope of its authority, which is very considerable in

school desegregation cases. Brown v. Boai^oyEduc^, 349

U S invesied the HIStrTct courts with “Broad

powers to grant relief from racial discrimination in the

public schools, and they were to be guided by equitable

nrinrinles in "fashioning and effectuating" decrees. Id.

I t 299 300. Pursuant to'this grant of power, federal courts

In school desegregation cases have ordered reopened a puhl,c

school system which had been closed to avoid desegregatio ,

v County School Bd. of prince Edward Countv, 3// U.S.

§1 5 ^ 6 4)-paired attendance areas high schools, D w ^ l

v sciool Bd'. of Oklahoma City, 244 F. Supp. 971 (W.B Okla

1965)T’aff'd 375 F.2d 158 (10th Cir.), cer^ ̂ enr|d^ 389 U .S.

847 (1967); placed a school system in receivorsh p -

-...x. a deseareqation order, Turner v. Goolsby, 22a F. Supp.

724 (S.D. Ga. 1965); and enjoined school construction pro^ec s,

tr Rnard of Public Educ. o:: Bibb County, 284 r; Supo. ̂

Iss Im .d ! GaT l9~67) , among"other^ictions indicating the brea

of remedial power available.

- 31 -

Thus, while H.E.W. recommended pairing Hale Elementary

(black) and Highland Gardens Elementary (white), the Board proposed

to close Hale, make only Negro students bear the brunt of

additional travel, and in fact assign some of the students not

to Highland Gardens but to Paterson, another all-black school.

These black students are thus denied the opportunity to receive an

integrated education (Highland Gardens will be 43.4% black —

almost exactly the community percentage — but Paterson will be

93.4% black). There is no dispute between plaintiffs and defendants

about the fact that there is occasional flooding of the Hale site,

or the need for its eventual closure or replacement. However,

plaintiffs sought and H.E.W. recommended (Tr. 116) that the

addition to Highland Gardens which the school district must construct

in order to absorb any students from Hale be made large enough to

house all former Hale students. Instead, the Board has assigned

former Hale students to overwhelmingly black Paterson in order

to avoid placing white students in a slight minority at Highland

Gardens.

Similarly, H.E.W. recommended pairing of McDavid and Forest

Avenue Elementaries. The schools are ideally suited for this

purpose, being located only about three blocks apart. pairing

would further seem an appropriate remedy since it is readily apparent

that the two schools were deliberately constructed for the purpose

of maintaining segregation - Forest Avenue having been enlarged

to accommodate the white students in the area in the same year

that McDavid was constructed. Once again, all the Negro students

from McDavid would not be accepted at Forest Avenue - to make

3

sure the white children were not placed in a minority. Many

Negro children will be denied the opportunity to attend an

integrated school — Forest Avenue will be 31.2% Negro -- due

to this deliberate action of the Board, and will be forced to

attend Booker T. Washington (91.4% Negro) and Paterson (93.4%

Negro).

Finally, the Board and H.E.W. proposed to close Booker T.

Washington High School, rather than assign white students to the

facility. Again, only Negro students were inconvenienced. They

were to be distributed among Lee, Lanier and Jeff Davis High

Schools but each of those schools would now be overcrowded (Tr. 79).

There would clearly have been no need to close one high school

had the board not deliberately constructed Jeff Davis to perpetuate

segregation, as the district court found in 1968.

in contrast, the students attending the predominantly white

schools which are closed suffer little or no disruption. cloverdale

which lost its elementary grades, is but four or five blocks from

Forest Avenue. Closing Pike Road, a rural school, and restructuring

Pintlala, also a rural school, meant little to students, most of

whom were already bused to school.

The position of the Negro students, particularly those from

Booker T. Washington Senior High School, who will be the cause of

overcrowding at the other schools, is similar to that observed in

a California case:

33

Where, however, the closing of an

apparently suitable Negro school and

transfer of its pupils back and forth

to white schools without similar

arrangements for white pupils, is not^

absolutely or reasonably necessary under

the particular circumstances, consideration

must be given to the fairly obvious fact

that such a plan places the burden of

desegregation entirely upon one racial group.

The minority children are placed in the

position of what may be described as

second-class pupils. White pupils realizing

that they are permitted to attend their own

neighborhood schools as usual, may come eo

regard themselves as "natives" and to resent

the Negro children bussed into the white schools

every day as intruding "foreigners. 1 It- is in

this respect that such a plan, when not

reasonably required under the circumstances,

becomes substantially discriminating in itself.

This undesirable result will not be nearly so

likely if the white children themselves realize

that some of their number are also required to

play the same role at Negro neighborhood schools.

Brice v. Landis, Civ. No. 51805 (N.D. Cal., August 8, 1969), slip

opinion at pp. 7-8.

It is doubtless true that the long-delayed integration of

dual school systems provides an opportunity to improve the

education of a LI students, black and white, by Eliminating

substandard school plants which would not have been maintained but

to preserve the segregated system. In many instances, such inferior

schools are the schools which served the Negro student population.

But this process should not serve as a ruse to make Negroes pay

for insisting upon desegregation by having the schools "traditionally

theirs" closed and their children subjected to inconvenience ir.

order to protect white children from attending the formerly Negro

facilities.

34

»: A-***-':-*--

£ ;f

Ths district court has already ordered the closing of the

small and inadequate schools which Montgomery County used as a

device to keep its school system segregated. Twenty-one such

facilities were ordered closed in 1965. 253 F.Supp. 306. The

remaining school plants are all reasonably adequate and ought to

be continued in use.

if"~ Judge Keady of the Northern District of Mississippi was

confronted with a situation similar to that below involving the

oxford Municipal school district, which had proposed to consolidate

its junior and senior high school grades on double sessions at the

former white high school, and to close the former Negro high school

rather than pair the facilities. His comments in refusing to

permit the district to undertake such a plan are relevant here:

The only reasons advanced which bear

upon the relative inadequacy of the

Central High School building are

limitations it may have with re^Pe^

to traffic conditions, playground arec ,

and other built-in deficiencies But

nevertheless, it is a usable plant, it

is in use at this time, it. has a

substantial replacement cost an« ^ i

needed by the board if it is to ^intai

its separate junior higi school and senior

high school programs. I

I think justice in this case requires that

this building be used and that rt pot b

terminated. To terminate it, frankly,

this court sees the present situation from

this evidence here today, ason

racial reasons. It would be tor one

that the white people ^re willing for the

colored children to come to the white sectro

of town to go to white schools but the white

people are not willing to let their children

go to the colored section. I think that i

the reason and we might as well tag it tor

what it is . • • •

35

Quarles v. Oxford Municipal Separate School Dist., Civ. No.

WC6962-K (N.D. Miss., January 7, 1970) (oral opinion at pp. 3-4).

in light of the 1966 order closing many small, inferior

segregated schools, we submit that the board's proposals to close

adequate all-black facilities in light of available options which

would integrate them, such as pairing, placed a heavy burden upon

the board to justify its decision on non-racial, educational grounds.

Quarles v. Oxford Municipal Separate School Dist.., supra; cf. e.g_. ,

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 (1964). That burden was not

met by the board in this case.

The principal reason for closing Booker T. Washington High

School, for example, was its small size in relation to other

Montgomery high schools. In fact, however, the school is not much

smaller than either Carver or Jeff Davis. Only Lanier and Lee

15/ . .

High Schools are significantly larger schools. Equally compelling

15/

Capa-

city

1969-70

Enrollment Year

W N Built

No. Students

Type Transported

Booker T. Washington

Carver

Jeff Davis

Lanier

Lee

900 0 785

1,250 0 1,097

1,375 1,102 113

2,250 1,814 286

2,200 1,994 132

1948 Brick 28

1948 Brick 232

1968 Brick 152

1929 Brick 427

1955 Brick 420

(Source: H.E.W. Plan)

36

*

is the fact that the 785 black students who attend Washington this

year cannot be contained in the white high schools among which

they are to be distributed. Those schools are but 384 students

under capacity this year, and in addition to the Booker T.

Washington students, they must absorb under the Board's plan an

additional182 students who will be transported from the Mt. Meigs

area, and who formerly attended the high school grades at Georgia

Washington school. And while the Washington site does not meet

State minimum site size requirements, the use of such standards is

akin to a racial standard - almost all black schools in Montgomery

were built on inadequate sites (Tr. 66-67).

The Board also failed to justify closing Hale and McDavid m

order to avoid pairing them with white schools. Its reasoning was

perhaps most transparent with respect to McDavid, whicn was built

at the same time as an addition to Forest Avenue, the school with

which it was to be paired. The Board's sole objection to McDavid,

other than one based on its racial identity, was the size of the

site. But this is so closely related to the racial characteristics

of Montgomery's schools that it cannot justify closing the school.

Since the case must be remanded to the district court, we

suggest the appropriateness of directions from this Court to (1)

retain McDavid and pair it with Forest Avenue Elementary; (2) take

further evidence and evaluate the proposed closing of Hale and

Booker T. Washington, and disallow the closings if they are in Y

part motivated by racial considerations; and (3) develop plans to

continue Washington as a desegregated school.

37

CONCLUSION

For all or the above reasons, the case should be remanded

to the district court with directions to require the development

and implementation of a plan to substantially integrate the

Montgomery County schools and thus create a unitary school system

in Montgomery County, Alabama not later than the commencement of

the 1970-71 school year.

Respectfully submitted,

352 Dexter Avenue

Montgomery, Alabama 36104

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Appellants

■

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that I served two (2) copies of the

Brief for Appellants upon counsel for the appellees and for

the united States, plaintiff-intervenor, by mailing same,

first class postage prepaid, addressed to each of them as

follows, this / / day of April, 1970:.

Vaughan H. Robison, Esquire

Hill, Robison, Belser & Phelps

36 South perry Street

Montgomery, Alabama 36104

Honorable Ira DeMent

4 United States Attorney

r P. 0. Box 197

* Montgomery, Alabama 36101

Robert P. pressman, Esquire

United States Department, of Justice

Washington, D.C.

t-*

39