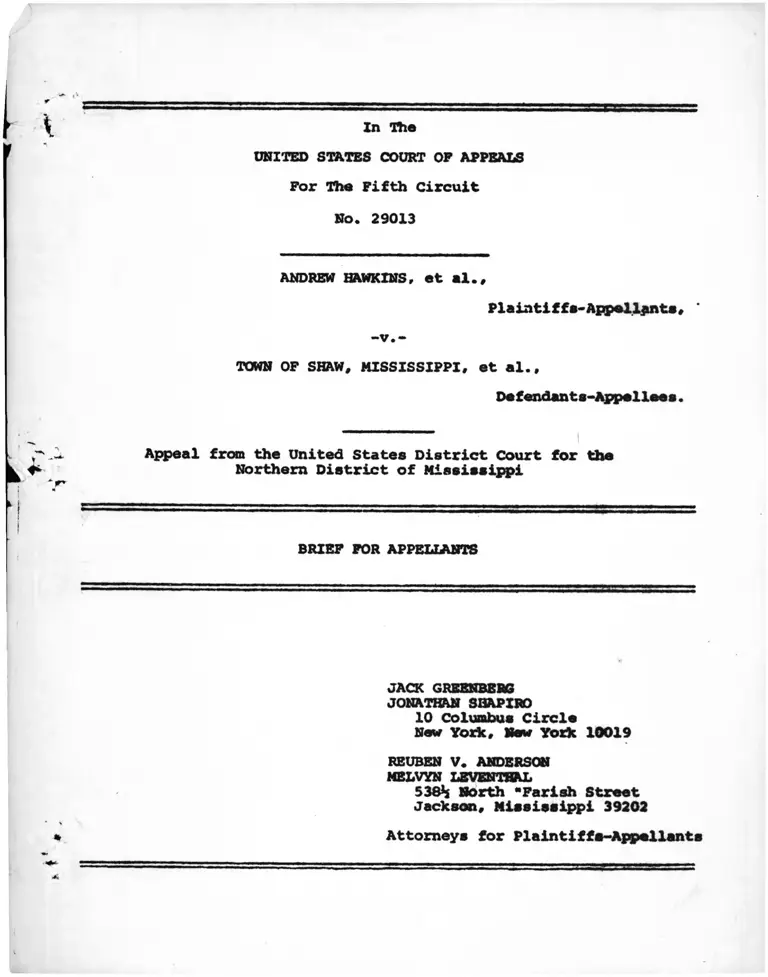

Hawkins v. Town of Shaw, MS Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hawkins v. Town of Shaw, MS Brief for Appellants, 1970. 6752eece-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/54d0fc87-c47b-4417-9c46-0c901d7b8a73/hawkins-v-town-of-shaw-ms-brief-for-appellants. Accessed March 12, 2026.

Copied!

r

\ In The

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

For Tha Fifth Circuit

No. 290X3

ANDREW HAWKINS, at al..

Plaintiffa-Appalljmta, *

-v.-

TOWN OF SHAW, MISSISSIPPI, at al.,

Defendants-Appalleas.

Appeal from the United States District Court for tha

Northern District of Mississippi

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

JACK GREENBERG

JONATHAN SHAPIRO

10 Columbus Circle New York, Mow York 10019

REUBEN V. ANDERSON

MELVYN LEVENTHAL

538% North "Parish Street

Jackson, Mississippi 39202

* Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appallants

I N D E X

Issues Presented ........................................... 1

Statement of the Case ....................................... 2

Statement of the Facts ...................................... 4

Summary of the Argument......... ............................ 11

Argument

I. The Court Below Erred In Failing To Apply A Strict Standard Of Review under The Equal Protection

Clause In The Face Of Plaintiffs' Showing Of A

De Facto Racial Classification In The Provision Of

Municipal Services ................................. 13

II. Defendants Have Failed To Meet Their Heavy Burden

Of Justifying Their Denial To The Black Residents

Of Shaw Of Equality In The Provision Of Municipal

Services And Facilities; And Plaintiffs Are Enti

tled To Injunctive Relief .......................... 24

III. The Court Below Erred In Holding That Equitable Re

lief Against The Town of Shaw Was Not Available In

A Suit To En oln The Deprivation Of Plaintiffs'

Right To The Equal Protection Of The L a w s ....... 49

Conclusion .................................................. 53

Table of Cases Page

Adams v. City of Park Ridge, 293 F.2d 585 (7th Cir. 1961) .... 50

Anderson v. City of Albany, 321 F.2d 649 (5th Cir. 1963)..... 51

Arrington v. City of Fairfield, 414 F.2d 687 (5th Cir. 1969).. 18

Bailey v. Patterson, 323 F.2d 201 (5th Cir. 1963), 376 U. S.910 (1964).............................................. 51

Baker v. Carr, 369 U. S. 186 (1962) ......................... 47

Bell v. Hood, 327 U. S. 678 (1946) .......................... 47

Bivens v. Six Unknown Agents, 409 F„2d 718 (2d Cir. 1969).... 51

Board of Public Instruction of Duval Co. v. Braxton, 325

F.2d 616 (5th Cir. 1964) ............................... 48

Brooks v. Beto, 366 F.2d 1 (5th Cir. en banc 1966).......... 20*47

Chavis v. Whitcomb, 305 F. Supp. 1364 (S.D. Ind. 1969)...... 18

Coleman v. Alabama, 389 U. S. 22 (1967) .................... 20

Cypress v. Newport News General and Nonsectarian Hospital

Hospital Ass'n, 375 F.2d 648 (4th Cir. 1967) ........... 19

Fortson v. Dorsey, 379 U. S. 433 (1965) ..................... 18

Gautreaux v. Chicago Housing Authority, 304 F. Supp. 736

(N.D. 111. 1969) ....................................... 48

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U. S. 339 (1960) ................ 22

Griffin v. School Board of Prince Edward County, 377 U. S.

218 (1964) ............................................. 48

Hadnott v. City of Prattville, No. 2886-N (M.D. Ala. Feb. 2,

1970) .................................................. 48

Hawkins v. North Carolina Dental Society, 355 F.2d 718

(4th Cir. 1966) ........................................ 19

Henry v. Clarksdale School District, 409 F.2d 682 (5th Cir.

(1969) ................................................. 39

Hobson v. Hansen, 269 F. Supp. 401 (D.C. Cir. 1968)... 16,17,20,23

Jackson v. Godwin, 400 F.2d 529 (5th Cir. 1968)...... 16,19.24.43

ii

Page

Kelly v. Page, 335 F.2d 114 (5th Cir, 1964) ................. 51

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U. S. 1 (1967) ...................... 13

McGowan v. Maryland, 366 U. S. 420 (1961) .... ............... 12

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U. S. 184 (1964) ............ 12,13,14,20

Mayhue v. City of Plantation, 375 F.2d 447 (5th Cir. 1967).... 51

Meredith v. Fair, 298 F.2d 696 (5th Cir, 1962)............. •• 19

Monroe v. Pape, 355 U. S. 167 (1960)....................... 49,50,51

Norwalk CORE v. Norwalk Redevelopment Agency, 395 F.2d 920

(2d Cir. 1968) ......................................... 13

Pitts v. Board of Trustees, 84 F. Supp. 975 (E.D. Ark. 1949).. 48

Patton v. Mississippi, 332 U. S. 463 (1947) ..... ............ 22

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U. S. 533 (1963) ...................... 47

Schnell v. City of Chicago, 407 F.2d 1084 (7th Cir, 1969).... 50

Shapiro v. Thompson, 394 U. S. 618 (1969) ................... 39

Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128 (1940) ....................... 17,19

Smuck v. Kansen, 408 F.2d 175 (D.C. Cir. 1969).............. 16

Southern Almeda Spanish Speaking Organization v. Union City,

No. 25,195 (9th Cir., Mar. 16, 1970) ................... 18,46

Swain v. Alabama, 330 U. S. 202 (1965) ..................... 20

United States v. Clark, 249 F.Supp. 720 (S.D. Ala. 1965) ...... 52

United States v. Holmes County, 385 F.2d 734 (5th Cir. 1967).. 51

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education, 380 F.

2d 385 (5th Cir. en banc 1967) .......................... 48

United States v. Richberg, 398 F.2d 523 (5th Cir. 1968) ..... 24

United States ex rel Seals v. Wiman, 304 F.2d 53 (5th Cir.

1952) ............. ..................................... 22

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U. S. 356 (1886) .................... 19

IV

\ Page

Statutes

42 United States Code, § 1983 3 ,49,50

Other Authorities

Note, Developments in the Law — Equal Protection, 82 Harv.

L. Rev. 1065, 1977-87 (1969) ............................. 12,17,45

Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disor

ders, 143-50 (Bantam Ed. 1968) ........................... 2

In The

UNITED STATES COURT OP APPEALS

For The Fifth Circuit

No. 29013

ANDREW HAWKINS, et al..

Plaintiffs-Appellants,-v. -

TOWN OF SHAW, MISSISSIPPI, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Northern District of Mississippi

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Issues Presented

1. Whether the court below erred in failing to require defendants

to meet the heavy burden under the Equal Protection Clause of estab

lishing overriding governmental interests to justify their provision of

a consistently inferior level of municipal services to the black resi

dents of Shaw, and in sanctioning instead this unequal treatment upon

a finding that it was supported by mere "rational considerations?"

2. Whether plaintiffs are entitled to equitable relief when the

record discloses no overriding governmental interest to justify the

unequal treatment of the black residents of Shaw?

3. Whether equitable relief may be granted against a municipal

ity in a suit to redress the violation of plaintiffs' rights to the

equal protection of the laws guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment of

the United States Constitution?

Statement of the Case

The central issue in this case is whether this Court will apply

the same standards of equal protection to the provision of municipal

services by a municipality that it has applied to the full range of

other governmental activities which historically have been tainted by

racial discrimination. At issue is whether this Court will condemn

the degrading inequalities in the provision of municipal services that

constitute one of the most tenacious badges of slavery in cities

throughout this nation.

Plaintiffs are representatives of a class of the impoverished

black residents of the Town of Shaw, Mississippi, who brought this

action on November 21, 1967 to enjoin the unequal provision of municipal

services to the black residents of the town (R. 368-375). They sought

to require the defendants — the Town, its Mayor, Aldermen and its

Clerk to equalize the provision of street paving, street lighting,

storm water drainage, traffic control, sanitary sewerage, water supply

and fire hydrants to the town's black and white residents.

Defendants' motion to dismiss the complaint (R. 376-377) was over

ruled as to the individual defendants and sustained as to the Town of

Shaw on July 12, 1963 (R. 410). In its unreported Memorandum Opinion

the court below held that proof of racial or economic discrimination

in the provision of municipal services would entitle plaintiffs to

-L/ Sef of t îe National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders.143-50 (Bantam Ed. 1 9 6 8 ) . ------------ -----------— ----

-2-

relief under 42 U.S.C. § 1983; that the suit was properly brought as

a class action; that the individual defendants were not immune from

suit; and that plaintiffs were not bound to have exhausted any avail

able state remedies prior to seeking federal relief (R. 404-409). As

to the municipality, the court held that it was not a "person" within

the meaning of 42 U.S.C. § 1983 and that injunctive relief against it

was not available (R. 408).

A trial was held on March 20, 21 and 22, 1969 at which time

testimony and documentary evidence was presented on the issue of the

equality of the municipal services and facilities provided to the

black and white residents of Shaw (R. 1-367). On September 19, 1969,

judgment was entered dismissing the complaint with prejudice and tax-

2/ing plaintiffs with all costs.(R. 574). The court applied the

traditional restrained standard of judicial review in equal protection

cases to the evidence. It stated the rule as follows:

If actions of public officials are shown to

have rested upon natural considerations, ir

respective of race or poverty, they are not

within the condemnation of the Fourteenth

Amendment, and their acts may not be proper

ly condemned upon judicial review. Persons

or groups who are treated differently must

be shown to be similarly situated and their

unequal treatment is demonstrated to be with

out any rational basis or is based upon an

invidious factor such as race (R. 570-71).

2/ Although the complaint alleged that there was discrimination on

the basis of both race and poverty, the proof showed that race

alone was the basis for discrimination in the provision of the

various services.

3/ The opinion of the court below is found at R. 559-573 and is

reported at 303 F. Supp. 1162 (N.D. Miss. 1969).

-3-

Although plaintiffs' statistical evidence was undisputed, and appar

ently accepted by the court, the court nevertheless denied relief on

the grounds that the consistent inferiority of the services provided

to the black neighborhoods was sufficiently explained and justified

on the basis of such rational considerations (R. 571-73). Having con

cluded that plaintiffs had not established a violation of the Equal

Protection Clause, the court did not consider the propriety of the in

junctive relief they sought and remitted them to the political process

es for relief (R. 573).

Plaintiffs perfected their appeal on October 2, 1969 (R. 575) and

cn December 9, 1969 they were granted leave by the district court to

appeal in forma pauperis (R. 613).

Statement of the Facts

The Town of Shaw, Mississippi was incorporated in 1886 and is

located deep in the Mississippi Delta. Its population, which has

undergone little change since 1930, consisted of 2,062 people accord

ing to the 1960 census, of which 1,327 were black, and presently con

sists of approximately 1,500 black and 1,000 white residents (R. 560).

The facts pertaining to the level of municipal services provided

to the different areas of the town are largely undisputed; only the

inferences to be drawn from these facts and their legal consequences

are at issue. The evidence relates to virtually all of the municipal

services that are essential to an urban environment; street paving,

street lighting, storm water drainage.- sanitary sewerage, water supply

-4-

fire hydrants; and traffic control. In the present case, this evi

dence discloses that there is a past and present correlation between

the areas of inferior municipal services in Shaw and the town's black

neighborhoods. It shows that black Mississippians, whose historic

denial of political, racial and educational equality has been re

corded in the opinions of this Court, have also been denied those

rudimentary features of municipal life that are enjoyed by white

residents.

Initially, it must be noted that residential racial segregation

in Shaw is almost total. There are 451 dwelling units occupied by

blacks in town. Of these, 437 (97%) are located in neighborhoods in

4/which no whites reside. Hie town's 231 houses occupied by whites

are similarly segregated. The exceptions are seven black homes that

are located outside of the areas of black racial concentration, and

another seven black homes that are located in proximity to ten white

homes. These neighborhood boundaries represent more than mere resi

dential segregation; they signify the division of Shaw into two sub

cities in which the municipal services are significantly unequal.

The statistics present a stark picture of an unrelieved pattern of

substantially inferior services and facilities in the black neighbor

hoods of town.

Almost 98% of the homes that front on unpaved streets in Shaw

5/are occupied by blacks. While approximately 56% of the black

4/ Appendix A, pp.la-2a,below, lists the white and black neighbor

hoods of Shaw with the number of houses in each.

5/ Appendix B, pp.3a-5a, below, lists all of the unpaved streets in Shaw and includes the number of houses and the race of the

occupants on each.

-5-

residents of town lived on unpaved streets at the time of trial, less

than 3% of the white residents did. Of the 35 presently unpaved

streets in Shaw, 33 are inhabited by blacks. The major proportion of

the streets in white residential neighborhoods, moreover, were paved

before the end of the 1930s, but no street in any black neighborhood

was paved before 1956.^ Indeed, 96% of the white residents lived on

3/paved streets by this time.

Closely related to the condition of the streets, is the extent

of storm water drainage that is provided. The absence of adequate

drainage vastly compounds the problems caused by unpaved streets De

cause accumulations of water turn unpaved streets into mud (R. 50).

Thus, in Shaw the hardship to the black residents of unpaved streets

is made worse because the drainage facilities in black neighborhoods

are uniformly worse than those in white neighborhoods. The court be

low recognized that "[u]nderground storm sewers exist largely in the

town's areas south of Porters Bayou and drainage ditches have also

been constructed" (R. 565). Indeed, the undisputed evidence shows

that underground storm sewers have been provided only in the town s

white areas south of Porters Bayou - 51% of the white population of

Shaw live on streets served by these sewers — and that the remainxn:

white areas have a continuous system of well-maintained drainage

fi/ Thus the court's statement at R. 571 that not until a .

BXZ is^Cleading?1

A VZSttX ved.̂ Before ^ ^

2/ See note 16, below.

-6-

ditches (R. 55-57). In contrast, the only storm water drainage in

the black neighborhoods consists of drainage ditches running along

several north-south streets with narrow, shallow ditches or no ditches

v &pt all provided to drain the east-west streets (R. 51-54). Although

there was agreement that all areas of Shaw have drainage problems be

cause of the poor drainage characteristics of Delta soil and because

the capacities of both bayous which flow through the town have been

overtaxed (R. 115), it is clear that the only substantial improvements

in drainage conditions have been made in white areas of the town (R.

56, 58).

The unpaved, poorly drained streets in the black neighborhoods

of Shaw are also poorly lighted in comparison with white residential

ptreets. Although black occupied homes account for 65% of the resi

dential dwelling units in town, the streets on which they front haveb

allocated only 44% of the residential street light fixtures; and white

homes which account for only 35% of the population have 56% of the

Ustreet light fixtures. But the quantitative difference in lighting

8/ Main drainage ditches in the black neighborhoods have been con

structed only on Lampton Street, Jackson Street, Railroad Avenue

and along the railroad right of way (R. 51-54).

9/ Plaintiffs' Exhibit No. 7, shows the location and type of all

the street light fixtures on a map of Shaw. Out of the total of

162 street lights located in residential areas, 71 are in black

neighborhoods and 91 are in white neighborhoods.

-7-

fixtures does not expose the full measure of the inferiority of street

lighting in the black neighborhoods to that in the white neighborhoods

There are two kinds of street light fixtures in use in Shaw — old ba.\

bulb incandescent fixtures that provide minimal illumination, and mod

em, powerful mercury vapor fixtures (R. 69-70). The court below

agreed that modem fixtures provide superior illumination and that

they had been installed only in areas occupied by white persons, whil-

the black areas were served by bare bulb lighting (R. 563). In fact,

77% of street lights in the white residential neighborhoods are of th

modern variety while not a single mercury vapor fixture has been in-

JS/stalled in a black residential neighborhood (R. 70).

Finally, the streets in the black neighborhoods of Shaw have

virtually no traffic control signs despite the numerous intersections

of local with through streets (R. 72). In the white neighborhoods, o-

the other hand, almost every intersection of any two streets, regard

less of how little used, has stop signs controlling traffic on one of

the streets (R. 72). The absence of traffic control signs on the

streets in black neighborhoods is consistent with the inequality of

the street facilities in all other respects.

A modern sanitary sewerage system of sewer mains emptying into

a lagoon south of town was completed in 1965, While this system

originally served every white home in town with the exception of two

isolated houses in the extreme northwest and southeast comers of the

10/ See Plaintiffs' Exhibit No. 7. Several mercury vapor fixtures are

located near black neighborhoods, but they serve commercial prop

erty only (R. 70). 70 out of the 91 street lights in white residential neighborhoods are medium or high intensity mercury vapor fixtures.

-8-

town (R. 209-10), it did not extend to approximately 35% (154) of the

black residences (R. 464). Despite several extensions to the system,

at the time of trial almost 20% (87) of the black residences were

12/still unserved by sanitary sewers (R. 211-12). The same 99% of the

white community, however, continued to be served. In the absence of

sanitary sewers, raw waste collects in drainage ditches throughout

%these areas and presents a very real health hazard to the black resi

dents (R. 62).

The town's water distribution system consists of pipes radia

ting from two wells in the central part of town. The same pipes

provide water for domestic use and for fire hydrants (R. 63). Al

though water is supplied to all residents of the town, the court below

noted that water pressure is inadequate in certain areas (R. 566).

The undisputed evidence established that the two areas where water

pressure was most inadequate was the black neighborhood in the north

east quadrant of town (the Gale Street area,located north of Silver

12/ In addition to the 87 black homes presently not served (see note

12, below) the sewer system originally did not extend to the fol

lowing streets in black neighborhoods on which 67 homes are lo

cated: Welbourne, Starkes, Manaway, Lacey, Lincoln, Bethlehem,

Canaan, Railroad Avenue and Mose Avenue. See Plaintiffs' Exhibit

No. 2 1 Defendants' Exhibit No. 5 and R. 207-08.

12/ The sanitary sewer system presently does not serve the following

black areas with a total of 87 homes: the entire Reeder Addition

(northwest quadrant of town) with 38 homes; Rogers Street (east of Route 61) with 8 homes; White Oak Street with 9 homes;

Issaquena Street with 3 homes; Elm Street (south of Mason Street)

with 14 homes; Canall Street with 9 homes; Railroad Avenue (north

of Mose Street) with 4 homes ;Wilson Avenue (west of Gale Street)

with 2 homes. See Defendants' Exhibit No. 5 and Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 2.

-9-

Bayou and east of the railroad tracks) and the black neighborhood in

the southwest quadrant of town (the "Promised Land"/ located south of

the town maintenance yard and east of the railroad tracks) (R. 251)

These areas are inhabited by 53% of the town's black population.

The reason for the inadequacy of the water system in these areas io

obvious. In the Gale Street area 211 homes are served by the same 4"

water main while in the Promised Land most of the 74 homes are served

13/

by 2" or I V mains. In contrast, most of the white community is

served by 6" water mains; and the 4" mains that are in white areas

JJy

serve far fewer residences than do the 4" mains in the black areas.

Fire hydrants are placed much less frequently in the black

neighborhoods than in the white neighborhoods, in the face of much

greater density of wooden houses (R. 65-57). The 437 homes in black

residential neighborhoods are served by only 23 fire hydrants while

the 244 homes in the white residential neighborhoods are served by 3x

hydrants. Thus, 65% of the population has access to only 42% of the

fire hydrants while 35% of the population has access to 58%. The

town engineer testified that in his opinion the entire eastern part

of the Promised Land, the entire Reeder Addition and Elm Street (south

13/ See Defendants' Exhibit No. 6.

14/ For example, the 211 black homes in Gale Street area (northeast

quadrant of town) are served by one 4" main that first passes

through a white neighborhood with only 34 homes. The pressure

atthe white homes is not affected by water use in the black neighborhood because the white homes are closer to the source o

the water. On the other hand, use of water in the white homes

will decrease the pressure at the black homes (R.64 ). Thesame is true for the white and black hemes west of the railroad

tracks and north of Porter's Bayou (northwest quadrant)in the

Reeder Addition.

-10-

of Mason Street) were without adequate fire protection because of

the absence of fire hydrants (R. 350-51). On the basis of his

standard for minimal fire protection, the western portion of the

Gale Street area, a portion of the Boatwright Addition and the air-

15/field street are also inadequately served. No white neighborhood,

however, had an insufficient number of hydrants on the basis of this

standard (R. 68). Although the court below correctly noted that th"

record does not conclusively establish that recent fire losses in tV.

black neighborhoods were attributable to the inadequate placement cf

hydrants or inadequate water pressure (R. 566) it is perhaps no

coincidence that in the period of one year preceding the trial seven

homes in the black areas were totally destroyed by fire, with the

loss of one life (R. 65-66).

Thus, the undisputed facts document the inferiority of the

municipal services and facilities enjoyed by the black residents of

Shaw in contrast to those enjoyed by white residents. The record

depicts a small town ghetto where black people are deprived of both

the necessities and the amenities of municipal life. Although the

black man has ostensibly been free for over one hundred years, the

badges of slavery are still reflected in the way he is forced to

live in Shaw.

Summary of the Argument

In the face of this proven disparity between the municipal ser

vices and facilities afforded to the black and the white residents

15/ The town engineer testified that at least two fire hydrants

should be located within 500 feet of each house for adequate

fire protection (R. 310, 350).

-11-

of Shaw, the court below found rational considerations that explain

ed and justified the inequalities. It concluded that this "unequal

treatment" did not violate the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment because plaintiffs had not demonstrated that rt

was "without any rational basis" (571). Thus, the court applied a

standard for evaluating plaintiffs' equal protection claim, tradi

tionally used in cases where fiscal and regulatory matters are at

issue, whereby the challenged discrimination is upheld so long as it

bears some national relationship to a legitimate state objective.

See McGowan v. Maryland, 366 U.S. 420, 425-26 (1961); Note,

Developments in the Law -- Equal Protection, 82 Harv. L. Rev. 1065,

1977-87 (1969. Indeed, it placed the burden on plaintiffs to show

either that the unequal treatment had no reasonable basis or that

its objective was invidious racial discrimination (R. 571).

We argue below that the court erred in its application of the

standards of the Equal Protection Clause to this record. We contend

that the unequal treatment of black persons as a class regardless of

whether their classification for such treatment has been de jure or

de facto, must be condemned unless an overriding governmental in

terest justifies such treatment. McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U. S.

379 U. S. 184 (1964). In the face of the proven fact that the

black residents of Shaw are receiving distinctly and systematically

less advantageous treatment in the provision of municipal services

than white residents, defendants are required to bear a very heavy

burden of justification. The decision of the court below, therefore

must be reversed because it condoned the unequal treatment of the

-12-

black residents of Shaw merely because plaintiffs had failed to show

that the inequality was not based on any "rational considerations."

Since the record in this case clearly demonstrates, moreover,

that there is no sufficiently compelling interest to justify the in

feriority of the municipal services provided to the black residents,

this Court should reverse and remand with directions to the district

court to consider the appropriate relief to remedy the violation of

the plaintiffs' right to the equal protection of the laws.

I

The Court Below Erred In Failing To Apply

A Strict Standard Of Review Under The

Eaual Protection Clause In The Face Of

Plaintiffs' Showing Of A De Facto Racial

Classification In The Provision Of Municipal

Services.

We begin with the proposition that a law which classifies per

sons by race "even though enacted pursuant to a valid state interest.,

bears a heavy burden of justification, . . . and will be upheld only

if it is necessary, and not merely rationally related, to the accom

plishment of a permissible state policy." McLaughlin v. Florida,

379 U. S. 184, 196 (1964). While a demonstration of a possible

rational foundation is sufficient under the Equal Protection Clause

to support a distinction not drawn according to race, e.g., where

taxation or economic regulation is involved, courts have required

that racial distinctions be supported by more than a mere rational

connection to a legitimate public purpose. See Loving v. Virginia,

-13-

388 U. S. 1, 8-9 (1967). This is so because:

. . . a classification based upon the

race of the participants . . . must

be viewed in light of the historical

fact that the central purpose of the

Fourteenth Amendment was to eliminate

racial discrimination emanating from

official sources in the states. This

strong policy renders racial classifi

cations "constitutionally suspect,"

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497, 499;

and subject to the "most rigid scrutiny,"

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S.

214, 216; and "in most circumstances

irrelevant" to any constitutionally

acceptable legislative purpose,

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S.

81, 100. McLaughlin v. Florida, supra

at 191-92.

Although the court below acknowledged that such a strict standar:

of review was applicable where racial classifications were involved

(R. 570), it avoided its application in the present case by conclud

ing that no racial classifications had been shown to exist with

respect to the provision of municipal services to the residents of

Shaw. The court said:

Plaintiffs have compiled certain statistics

which they claim support a charge that de

fendants and their predecessors in office

have racially classified the black and white

neighborhoods by providing better or more

complete facilities to the latter neighbor

hoods, but they would ignore all legitimate

deductions to be made from the evidence

running counter to statistical racial dis

parity. But we do not understand that a

court may adopt that manner of reasoning.

If actions of public officials are shown to

have rested upon rational considerations,

irrespective of race or poverty, they are

not within the condemnation of the Fourteenth

Amendment, and may not be properly condemned

upon judicial review. Persons or groups who

-14-

are treated differently must be shown to be

similarly situated and their unequal treat

ment demonstrated to be without any rational

basis or based upon an invidious factor such

as race (R. 570-71) (emphasis added*)"!

In evaluating plaintiffs' equal protection claim the district

court was apparently applying a two step analysis: first determine

whether defendants had "racially classified the black and white

neighborhoods" and then, only if a racial classification had been

shown, determine whether the racial classification can withstand the

"strict scrutiny" required by the Equal Protection Clause. But in the

present case the court never reached the second step. After the court

made "all legitimate deductions . . . from the evidence running counter

t;o statistical racial disparity, " it concluded simply that they "nega

tive plaintiffs' assertions of racial and economic discrimination"

(R. 573).

The court's error is plain. In effect, the district court equated

"racial classification" and "racial discrimination." Its analysis in

dicates that it thought that plaintiffs must show that defendants

intended to treat the black residents differently as a class in order

to establish the existence of a "racial classification." When the sep

arate treatment was explained by rational considerations, other than

race, it followed, according to the district court, that there had

been no racial classification. And without any racial classification

it further followed that there had been no racial discrimination. Thus,

as a result of this tortuous reasoning the court reviewed the undis

puted evidence that the black residents of Shaw had systematically re

ceived municipal services that were distinctly inferior to those

-15-

provided to the white residents under the traditional standard where

government action is upheld unless shown to be without any rational

basis instead of under the strict standard applicable where racial

classifications are involved.

Such an analysis misconstrues completely the review of

"suspect classifications" mandated by the Equal Protection Clause.

For by placing an initial burden on plaintiffs to establish an in

tentional differential treatment of the races by defendants, the courti

c.eriously limits the utility of the strict standard of review. Under

this reasoning the strict standard would apply only where the racial

classification is made explicit, as on the face of a statute, or

where the plaintiffs are able to meet a difficult burden of either

proving intent affirmatively or excluding all rational hypotheses

other than race on which the evidence can be explained. Indeed, in

such cases finding intentional differential treatment would be tan

tamount to finding intentional racial discrimination and no further

inquiry would be necessary.

A strict standard of review must be applied whenever govern

mental action results, for whatever reason, in the isolation of a disad

vantaged racial minority for differential treatment. Jackson v.

Godwin, 400 F.2d 529 (5th Cir. 1968); Hobson v. Hansen. 269 F.

gupp. 401 (D.C. Cir. 1968), aff'd sub nom. Smuck v. Hansen. 40e F.2d

175 (D.C. Cir. 1969). In such cases, the Equal Protection Clause

commands the use of the more stringent standard both because of the

-16-

that the differential treatment is a product of invidious

racial discrimination and because the differential treatment, in

itself, is perceived as a "stigma of inferiority and a badge of

opprobrium" by the affected class. See Developments In The Law —

Egual Protection. 82 Harv. L. Rev. 1065, 1127 (1969). A de facto

racial classification is just as much evidence of forbidden racial

motivation and the resulting social evil is just as great as when

the classification is established by law. And it cannot be permittee

to continue unless the government has a compelling justification for

the inequality.

Thus, the Supreme Court has condemned racial discrimination

"whether accomplished ingeniously or ingenuously." Smith v. Texas.

311 U. S. 128, 132 (1940). And echoing this principle. Judge Skelly

Wright recently wrote:

Whatever the law was once, it is a testament

to our maturing concept of equality that,

with the help of Supreme Court decisions in

the last decade, we now firmly recognize

that the arbitrary quality of thoughtless

ness can be as disastrous and unfair to

private rights and the public interest as

the perversity of a willful scheme. . . .

[T]he element of deliberate discrimination

is - - . not one of the requisites of an equal protection violation; and given the

high standards which pertain when racial

minorities . . . are denied [equality] . . .

justification must be in terms . . . of pos

itive social interests protected or advanced.Hobson v. Hansen, supra. 269 F. Supp. at 497-98.

It is the effect of governmental action on racial minorities,

therefore, rather than its actuating motive or intent, that is rel

evant for the purpose of the Equal Protection Clause. With respect

-17-

to voting rights, for example, the Supreme Court has invalidated

apportionment schemes that "designedly or otherwise" operate to min

imize the voting strength of a racial minority. Fortgon v. Dorsey,

379 U. S. 433, 439 (1965); see Chavis v. Whitcomb, 305 F. Supp. 1364

(S.D. Ind. 1969) (three judge court). Both this Court and the

Second Circuit have held that even in the absence of intentional dis

crimination, the action of public officials which disproportionately

disadvantages racial minorities constitutes a violation of the Equa

Protection Clause. Arrington v. City of__Fairfield, 414 F.2d 687

(5th Cir. 1969); Norwalk CORE v. Norwalk Redevelopment Agency, 395

F.2d 920 (2d Cir. 1968). And even more recently the Ninth Circuit

recognized that the repeal of a rezoning ordinance which resulted in

the denial of decent housing and an integrated environment to the

low-income, minority group residents of a city might constitute a

denial of the equal protection of the laws, regardless of the motive

for the reoeal. Southern Almeda Spanish Speaking Organization v.

f*

Union City, No. 25,195 (9th Cir. Mar. 16, 1970).

The court below erred in believing that there has to be an ele

ment of intent, deliberateness or actual discrimination in the

creation of a racial classification. Rather, as the decisions of th_

Court have established, what triggers a strict standard of review is

the existence of a disparity between the treatment accorded to a dis

advantaged racial group and that accorded to others, regardless of

motive or intent. Accordingly, in the absence of an overriding jus

tification, rules and regulations which are nondiscriminatory on

their face bur which in practice and effect impose a heavier burden

-’18-

on black people than on whites have been condemned. In Jackson v.

Godwin. 400 F.2d 529 (5th Cir. 1968), this Court concluded that even-

handed, non-arbitrary enforcement of prison newspaper and magazine

regulations that had the effect of imposing far greater restrictions

on the reading materials allowed to black prisoners than to white

prisoners nevertheless violated the Equal Protection Clause, when the

prison officials could offer no compelling justification for their

policies. And in Meredith v. Fair, 298 F.2d 696 (5th Cir. 1962), a

state institution's facially neutral admission requirement that appli

cants furnish recommendations from alumni was invalidated because of

its effective exclusion of black students. See also Hawkins v. North

Carolina Dental Society. 355 F.2d 718 (4th Cir. 1966); Cypress v.

Newport News General and Nonsectarian Hospital Ass'n., 375 F.2d 648

(4th Cir. 1967).

Even more pertinent to the present case are the cases which

have struck down de facto racial classifications that have resulted

only from official administrative action over a long period of time.

In the classic case of Yick Wo v. Hopkins. 118 U. S. 356 (1886), the

Supreme Court held that the unexplained evidence that only Chinese

laundrymen had been denied permission to operate laundries in wooden

buildings while white persons had been granted permission established

a violation of the Equal Protection Clause. Long continued dispari

ties between the proportion of black people on juries and their pro

portion of the population have long been held to constitute a racial

classification which, when not explained or sufficiently justified,

violates equal protection. Smith v. Texas. 311 U. S. 128, 132 (1940);

-19-

Coleman v. Alabama, 389 U. S. 22, 23 (1967); Brooks v. Beto, 366 F.2d

1# 12-13 (5th Cir. en banc 1966); cf. Swain v. Alabama. 380 U. S. 202

(1965). And Hobson v. Hansen, supra, held that a pattern of de facto

school segregation brought about by a series of facially nondiscrim-

inatory school board policies came "freighted with a 'heavy burden of

justification.' " 269 F. Supp. at 506.

The question in the present case, then, is whether defendants'

actions have resulted in such a racial classification of the black

and white residents of Shaw with respect to the level of municipal

services provided. As pointed out above, it matters not whether the

disadvantageous treatment of black residents as a class was accom

plished "ingeniously or ingenuously" — through the "perversity of a

willful scheme" or as a result of the "arbitrary quality of thought

lessness." If there has been de facto unequal treatment of the black

residents in Shaw, then the actions of defendants that resulted in

such treatment must be subjected to a searching review. It is our

contention that the record in the present case clearly establishes

the existence of such a de facto racial classification in the provi

sion of municipal services and that the court below committed rever

sible error in sanctioning the unequal treatment of the black resident

without requiring defendants to meet their "heavy burden of justifi

cation." McLaughlin v. Florida, supra.

As we detailed above in the Statement of Facts, the level of

every municipal service provided to the black residents of Shaw is

inferior to the level of these services provided to the white resi

dents. This is true of street paving, surface water drainage, street

-20-

lighting, traffic control, sanitary sewerage, water supply and the

placement of fire hydrants.

The disparity in each case is substantial: 98% of the white

residents of Shaw live on paved streets as compared to only 42% of

the black residents? virtually all of the white residential areas

are served by underground storm sewers or well-maintained drainage

ditches in contrast to a primitive, uncontinuous system that does

not serve most of the streets in the black neighborhoods? over 75% of

the street lights in the white neighborhoods are modern mercury vapor

fixtures as compared to only old bare bulb fixtures in the black

neighborhoods? almost every intersection of streets in white neigh

borhoods is governed by traffic control signs as compared to none in

the black neighborhoods? only two white homes are unserved by sani

tary sewers as compared to almost 20% of the black homes which are

without sanitary sewerage? at least 63% of the black residents live

in areas where the water supply is inadequate while all white resi

dents are adequately served? and many parts of the black neighborhoods

but no parts of white neighborhoods are inadequately protected by

fire hydrants.

In each case, moveover, the disparities have existed over a

long period of time. As of 1948, 96% of the white residents of Shaw

lived on paved streets while only 3% of black residents lived on pavec

streets. In 1956, 98% of the white residents lived on paved

streets while less than 20% of the black residents had paved streets.

And in 1967, when this suit was filed over 70% of the black residents

still lived on unpaved streets. All of the white residents of town

-21-

have been served by water mains at least since 1950, but the black

residents of the Promised Land addition, the Reeder Addition and the

eastern part of the Gale Street area were not supplied with water

lb/until 1957 and 1961. In 1965 when the sanitary sewerage system

was installed at least one-third of the black community was unserved

while all but two white residents were served. And the black neigh

borhoods have neverhad any mercury vapor lights since they first began

to be installed in 1962 (R. 515).

Such long continued, substantial disparities between the level

of municipal services provided to the black and white residents of

Shaw clearly establishes a de facto racial classification. United

States ex rel Seals v. Wiman, 304 F.2d 53 (5th Cir. 1962); see

Gomillion v. Lightfoot. 364 U. S. 339 (1960); Patton v. Mississippi,

332 U. S. 463 (1947). And in the face of such a classification the

court below should have required the defendants to show compelling or

overriding interests which justified the unequal treatment of blacks.

Instead of placing this heavy burden on defendants, the court placed

the burden on plaintiffs to demonstrate that the unequal treatment

was "without any rational basis or based upon an invidious factor

such as race" (R. 571). This was error. The court should have eval

uated evidence in light of the stringent standard commanded by the

Equal Protection Clause when a "suspect" racial classification has

been established instead of under a traditional standard which pre

sumes the regularity of official action.

16 ̂ See p. 42 , below.

-22-

We show in Point II, below, that the record does not disclose

any sufficiently compelling justification by which defendants' unequal

treatment of the black residents of Shaw can escape condemnation undex

the Equal Protection Clause. Suffice it to point out here that the

district court's judgment should be reversed if only because it ap

plied an incorrect standard of law to the evidence. The standard it

did apply would completely undermine the rule requiring courts to

strictly scrutinize "suspect" classifications. Its decision substan

tially dulls the Equal Protection Clause "as the cu.tting edge of our

expanding constitutional liberty," Hobson v. Hansen, supra, 269 P.

Supp. at 493, and seriously weakens the constitutional protections

against racial discrimination.

-23-

II

Defendants Have Failed To Meet Their

Heavy Burden of Justifying Their

Denial To The Black Residents Of Shaw

Of Equality In The Provision Of

Municipal Services And Facilities; And

Plaintiffs ~Are Entitled To Injunctive

Relief.

Although this case might appropriately be reversed and

remanded to the district court for the purpose of making findings

cf fact in light of the correct standard of law, this Court can and

should, on the basis of the undisputed facts in the record, hold

that plaintiffs have been denied their right to the equal protection

of the laws and direct the district court to grant them injunctive

relief. Jackson v. Godwin, 400 F.2d 529 (5th Cir. 1968); Phited

States v. Richberg. 398 F.2d 523 (5th Cir. 1968). It is manifest

that defendants have not met their heavy burden of justifying the

inferior municipal services provided to the black residents of Shaw.

They have not met this burden in two respects. First, they

failed to show that the disparities in the provision of services

were the result of the even-handed application of rational policies.

If such policies had in fact been adopted by defendants, they were

administered arbitrarily to the detriment of the town's black

residents. Secondly, those policies which were non-arbitrarily

administered but which in practice and effect disadvantaged black

residents did not serve any compelling governmental interest.

In general, defendants contended that the priorities for the

provision of municipal services to the residents of the town were

-24-

determined on the basis of either the need that existed for the

particular service or the feasibility of providing the service.

Thus, they argued that wherever the needs were the same the same

levels of services were provided, except where it was not feasible

or impossible to provide the service. Although the provision of

municipal services to residents of a town on the basis of need and

feasibility may well be such compelling governmental interests to

justify a racial disparity, we establish below that in the

present case such standards were clearly not applied in an even-

handed manner and that, in any case, the explanations that were

advanced as justifications for the disparities were not sufficiently

compelling.

A. Street Paving

The district court concluded that as a result of the "cautious

fiscal policy" that dominated the town until 1955 none of the

"residential streets in white or black neighborhoods [were]

asphalted except those forming a state highway, or fronting upon

commercial or industrial enterprises, or serving school or other

public buildings" (R. 571). The evidence, however, is otherwise.

In 1956 when the first residential streets in black neighborhoods

were paved, 96% of the white residents of Shaw lived on paved streets.

IS/most of which had been paved during the 1930’s. The paving of

i f-J See Appendix C ., below. The only streets in the white neigh

borhoods that were unpaved in 1956 were Baronet, Elm (from the

intersection with Alexander north until the end of the present pave

ment) , Faison (for one block south of Jefferson Street), Ellwood (from New West to the cemetery), the alley adjacent to the cemetery,

Doran, and Jackson Street extended (north of Porter's Bayou). There

are only XL white homes that front on all of these streets.

-25-

these streets cannot be explained solely on the basis of their

relationship to highways, to commercial or industrial enterprises,

to schools or to other public buildings. For many were solely

residential streets that did not even arguably serve commercial,

industrial or any public buildings. Such streets were: Jackson

Street, Jefferson Blvd., School Street (streetimmediately east of

17/the school), Faison Street, Dean Blvd. (east of route 61), Bolivar

Street, Walker Street, Mason Avenue, Stephens Street, New West18/

Street, Grant Street, Alexander Street, Bayou Street and Gale Street

(from Bayou Street to the Silver Bayou). It is apparent that these

streets did not serve a "great majority of the town's inhabitants"

and were not "heavily traveled streets."

On the other hand, the streets in the black neighborhoods

that did have special functions remained unpaved prior to 1956.

Although Gale Street and White Oak Street were part of the old

U. S. highv;ay 61 (R. 239), the sections of these streets that ran

through black neighborhoods were not paved until 1956. While all

of the streets serving and surrounding the white school were paved

long prior to 1956, the streets serving the school black children

17/ Although School Street, Faison Street and part of Jefferson

Street are all adjacent to the property on which the school is

located, it is clear that they all do not carry a significant

amount of school traffic.

18/ The factory at the intersection at Grant and New West Streets

was not constructed until 1962 (R. 507-08).

-26-

attended (White Oak and Bethlehem Streets) were also unpaved until

1 q/1956. And although the decision to pave Ellwood Street west of

New West Street and the adjacent alley was explained on the ground

that it served the white cemetery, defendants have never paved

Issaquena Street which serves the black cemetery (R. 318-19).

Thus, if the use of streets as highways and their relationship to

commercial, industrial or public buildings were the factors which

determined the paving of streets prior to 1955, these standards

were applied arbitrarily to the detriment of the black neighbor

hoods .

The overall conclusion of the district court that street

paving has usually been based upon "general usage, traffic needs,

adequate rights of way and other objective criteria" (R. 572) is

also refuted by the record. Indeed, the town engineer who made

recommendations to defendants as to the priority of street paving

projects testified that he had never surveyed the town to deter

mine which streets were used the most (R. 315) or compared the

usage of streets in black neighborhoods with the usage of those

in white neighborhoods (R. 316). He admitted that he was not even

familiar with the usage of streets in the Promised Land Addition,

one of the oldest and largest black neighborhoods in town (R. 323).

In fact, he recognized that a usage criterion had not been applied

consistently in the decisions as to which streets to pave (R. 320-

23) .

19/ The black school occupied the building which is presently the

site of the head start center at the corner of Bethlehem and

Canaan Streets.

-27-

The actual paving that was done reinforces the conclusion

that usage was not a determinative factor. The evidence of greater

density of housing and consequently greater intensity of use on

local streets in black neighborhoods was not challenged by defend-

20/

ants (R. 43-44). Yet, all but seven white homes (3 of which were

constructed only recently (R. 40))front on unpaved streets while

almost 60% of the black residents live on unpaved streets. Many

white residential streets, moreover, are paved even though there

is a minimal amount of traffic on them. For example, Jackson Street

extended (north of Porter's Bayou — sometimes referred to as

Baker Street) has only one house, Ellwood Street has only one house.

Mason Avenue is an alley with no houses fronting on it, Walker

Street has two houses, and Baronet Street has one house.

The other explanations that the district court accepted to

justify the disparity in street paving were based on the unfeasi

bility of paving streets in black neighborhoods. According to the

court, the unpaved streets in the Reeder Addition and in the Gale

Street area (Johnson Addition) on which approximately 30% of the

black population live were too narrow to permit paving without

acquiring additional rights of way from abutting property owners

(R. 563, fn. 5). It apparently based this conclusion on the testi

mony of the Mayor and the town engineer as to their adherence to a

20/ See Plaintiffs' Exhibit No. 2.

21/ See Appendix b .

22/ See Plaintiffs' Exhibit No. 2, pp. 2, 4.

-28-

nondiscriminatory policy of not paving streets that were too

narrow to pave (R. 243, 335). The engineer testified that streets

in black neighborhoods had not been paved because they did not have

the 50 foot right-of-way that he considered necessary in order to

construct an adequate street (R. 285). But if this objective

standard was ever actually a policy of the town, it is plain that

it was never enforced in any neighborhood, black or white. On the

basis of the 50 foot minimum right of way, there are only sixteen

streets in the entire town that have platted rights of way of 50

23/feet or more. Most of the streets, in both black and white neigh-

2A/borhoods, have platted rights of way that range from 30 to 40 feet.

A comparison of the "narrow" dedicated rights of way in white

neighborhoods that the town has paved with the "narrow" dedicated

rights of way in black neighborhoods that the town has not paved

clearly reveals the hollowness of defendants' claim that the width

of rights of way was an objective factor governing paving priori

ties :

23/ They are Jefferson Blvd. (50‘), Dean Blvd. (50'-60'), part of

Jackson Street (70*), Gibert Street (60'), School Street (70'),

Baronet Street (70’), Stephens Street (50'), Main Street (50*),

part of Faison Street (100*), Buckhalter Street (50'), Cleveland

Street (50'), Kelly Street (50*), Lipe Street (50'), Cohea Street

(50'), Lincoln Avenue (50*) and Douglas Avenue (50'). The last seven streets are located in black neighborhoods and three of them

are unpaved.

24/ See Defendants' Exhibit No. 4.

-29-

Dedicated

Paved White Right of Dedicated Right

Street Way (in ft.) Unpaved Black St. of Wav (in ft.)

Walker St. 30 Canall St. 30

Mason Ave. 30 Johnson Ave. 30

Ellwood St. 40 Boatwright St. 40

Grant St. 40 South St. 40

New West St. 40 Dorsey St. 40

Doran St. 25 Ricks St. 30

Jackson St.

Fxtended

(oet. Doran and Bayou) 25 Scott St. (west

of Gale) 30

Alexander St. 30-35 Issaquena St. 32

In addition, the defendants have paved the alley running between

Ellwood Street and Front Street, adjacent to the white cemetery,

which has a dedicated right-of-way of less than 20 feet. On the

other hand, Douglas and Lincoln Avenues in the Promised Land

Addition have dedicated rights-of-wav of 50 feet and have never

25/

been paved.

It is painfully evident, therefore, that the width of streets,

in Shaw had little or no effect on the decision as to which streets

to pave. If anything, the 50 foot wide right-of-way criterion was

honored more in its breach than in its enforcement. It does not

provide even the slightest justification for the disparities in

paving between the white and black neighborhoods. Even if there

25/ See Defendants' Exhibit No. 4.

-30-

were a need in certain cases to acquire additional rights-of-way

in order to make paving of black streets feasible, moreover, the

added difficulty in making such acquisitions is not a compelling

justification for the failure of defendants to pave streets in

black neighborhoods for decades. In fact, the testimony showed

that it '’as not any difficulty in acquiring additional rights of

way that prevented the town from doing so. Rather, the town had

never made any efforts either to acquire them or to determine

whether or not they had been acquired by prescription or adverse

23/possession (R. 337-340).

Several other purported justifications for the disparity in

the extent of paving in the black and white neighborhoods can be

briefly disposed of. The court concluded that the streets in the

Promised Land Addition, some of which are among the widest in town,

"have not been paved because of the necessity for first installing

new water mains cn the rights of way" (R. 563, fn.5). But the fact

that in 1969 the town decided to install new water mains next to

unpaved streets does not explain or justify its failure to pave

26/ For example, the official town map shows the dedicated right

of way of Bryant Street (Elm Street extended north of Porter s Bayou) to be 20 feet wide from Alexander Street to the city limits.

The evidence shows, however, that this street has been maintame by the town as an actual street for as long as anyone could recall

with a road bed of 15-16 feet wide and an apparent right of way

(including drainage) of 25 feet. This street is paved in front of

white homes from Alexander Street to Clinton Street where the road

bed is 15 feet wide but is unpaved north of Clinton Street where

the roadbed is 3.6 feet wide but which is in a black neighborhood

(R. 326-27; see Plaintiffs* Exhibit No. 3).

-31-

these streets for the preceding twenty or thirty years (R. 324).

The court also explained the resurfacing of streets in white neigh

borhoods in 1966 at a time when over 70% of the streets in black

neighborhoods were unpaved on the basis of the need, for proper

maintenance, to resurface streets every five years (R. 563, 286).

But the evidence shows that none of the streets in town have ever

been resurfaced within five or six years from the time they were28/

first paved. Instead, the white residential streets that were

resurfaced in 1966 and 1967 had been paved either in 1943 or 1956.

Oily one black residential street that had been paved in 1956 has

ever been resurfaced (R. 319-20). With only a few exceptions,

moreover, the streets in white neighborhoods that were resurfaced

29/in 1966 ana 1967 were not "heavily traveled downtown streets."

It is apparent, therefore, that there was no overriding need to

resurface v/hite residential streets before paving black streets30/for the first time.

27/

21/ The court might appropriately consider the need to install

water mains prior to paving streets in determining the relief to

whicn plaintiffs are entitled. Thus, the court might require

defendants to equalize water supply facilities before paving the streets.

_2§/ See Defendants' Exhibit No. 4.

—3/ Only Holly, Gibert and part of Dean Streets which were resur

faced in 1967, are arguably heavily traveled residential streets

located in the cowntoyn area. The remainder of the white streets

that were resurfaced in these two years are clearly local, residential streets, i.e., Bolivar, Dean (east of Route 61), Jefferson

School, Jackson, Baronet, Faison, Grant, New West, Ellwood and Cemetery Alley. See Defendants' Exhibit No. 4.

IS/ The engineer's testimony that some streets that had not been

resurfaced for 13 years were still in "fairly good shape" further

demonstrates that the resurfacing of these white streets could have waited several years at the least (R. 331).

-32-

B. Furface Water Drainage

There was no dispute that both bayous that flow through Shaw

are inadequate to accommodate the surface water drainage after large

rains and are subject to periodic overflowing (R. 136-37, 227, 306-

07). But neither was there any dispute that the town has dealt

unequally with the drainage problem in the white and black neigh

borhoods (R. 115) . VThereas the white neighborhoods have been pro

vided with either underground storm sewers (a system where water

drains through catch basins alongside the streets into underground

sewer mains which channel it into Porter's Bayou) or a continuous

system of well-maintained drainage ditches which channel surface

water into the underground system or directly into the bayou (R. 54-

57), the black neighborhoods have been provided with, at best, a

primitive, virtually nonfunctional system of poorly maintained

drainage ditches or, on many streets,no ditches at all (R. 51-54).

The results of this disparity in the efforts to improve drain

age conditions is that in the black neighborhoods surface water

remains on streets and in yards, turning them into mud and making

the passage of people and vehicles difficult and hazardous (R. 53).

Where there are no sanitary sewers raw sewerage also accumulates

with the surface water and constitutes a serious health hazard

(R. 53, 59). On the other hand, despite occasional overflowing of

Porter's Bayou and an area on the school property at the corner of

Dean Blvd. and Faison Street where drainage is poor, water drains

much more rapidly from the white neighborhoods and the streets

remain passable in all weather (R. 56). Although a heavy rain

-33-

might cause overflowing of both bayous, it was clear frcm observation

that considerably less rain is necessary to produce hazardous and

inconvenient conditions in the black areas because of the inferiorA /

drainage facilities and the unpaved streets^ Finally, defendants'

engineer admitted that the existence of a system of functional

drainage ditches would improve the conditions of the areas presently

without them (R. 344-45).

Thus, the existence of a problem that is common to both the

white and black neighborhoods of town cannot provide defendants

with any justification for their unequal efforts in providing a

solution.

C- Street Lighting

Although the court recognised that mercury vapor street lights

had been installed in white residential areas and only bare bulb

fixtures were in use in black areas, it nevertheless accepted

defendants' explanation that the "brighter lights are provided for

J ^ r t e r N tovouN N N bJS?® j n . th e w h ite a r e a s o f a d ja c e n t to

™ Thto - d r a in in g t ^ N h i t e N e ig h b o rh o o d s ^ S i S S N i X ^ * * 17

S : - bT - - on̂ ^Ln°I

without- !*you* Because water frcm the unpaved and ungraded areas

Porter's Bavo^via Silveriavou^he ‘l*?3 l0nger t0 drain into n-e i-urs „ t. • V1“ . iVer Bayou, the white areas eniov the benefit

?romet S P™ ltY °t Porter:s Bayou to accommodate the ?apid ditches. P V€Q streets with underground sewers and drainage

-34-

those streets forming either a state highway, or serving commercial,

industrial or special schools needs, or otherwise carrying the

heaviest traffic load" (R. 563). Again, a review of the record

makes clear that if these alleged objective standards for the

allocation of street lighting v/ere used, they were not applied

equally for the benefit of both black and white citizens.

The state highway that the court concluded justified the

brighter lighting is Front Street, which runs from east to west

through the town along the south bank of Porter's Bayou. That the

intensive lighting along this street is unrelated to its traffic

load is evident from the fact that Bayou Street, which runs along

the north bank of Porter's Bayou and is not part of any highway

and is not even a through street, is just as intensively lit.

Indeed, on the approximately 1700 foot stretch of Front Street

from Route 61 to Gale Street there are many more lights than on the

remaining portion of Front Street (excluding the business district)

or along the entire one mile length of the more heavily traveled

Route 61 w'ithin the town limits. The mercury vapor lights on Front

and Bayou Streets along this stretch of Porter's Bayou account for

25% of all of the mercury vapor lights in town. Their obvious

purpose is not to light a state highway but rather to light the

Bayou and its parklike banks for the benefit of the white residents

who live there.

22/ See Plaintiff's Exhibit No. 7.

The other explanations offered by defendants are equally

unsubstantial. Although there is a factory at the intersection of

the Grant and New West Streets, there is no apparent need for street

lights since it does not operate at night or stimulate an unusual

level of traffic (R. 90). Similarly, defendants would justify the

superior lighting along Dean Boulevard on the basis of the commer

cial and industrial areas at the corner of Dean and White Oak. But,

if these industries ever operate at night it is only the period in

the Fall when cotton is ginned (R. 92). Finally, the mercury vapor

fixtures on parts of Dean Boulevard, Faison Street, Jefferson

Boulevard and School Street are allegedly for the purpose of dis

couraging vandalism at the white school and the use of streets as

a lovers' lane (R. 236).

Even if we accept these explanations, the fact remains that

the improved lighting benefits only the white residents of town.

And in such a case, the inequality must be supported by "compelling"

rather than merely "rational" considerations. We submit that the

beautification of the banks of Porter's Bayou, the nighttime

traffic during ginning season, vandalism and a lovers' lane at the

white school are not sufficiently compelling reasons to justify

stigmatizing the entire black community of Shaw with old and

inferior street lighting.

This is particularly true since these criteria were not

uniformly applied in both black and white neighborhoods. If the

intensity of street lighting were dependent upon the amount of

traffic, then Gale Street, which is one of the most heavily

-36-

traveled streets in tovm since it provides the town's largest

black neighborhood with access to the business district and is the

shortest route from the business district to Cleveland, Mississippi,

should be lit by mercury vapor fixtures instead of bare bulbs (R.

72). Conversely, little traveled streets in white neighborhoods

such as Bayou Street, Jefferson Boulevard, between Jackson and

School Streets, part of Jackson Street, and part of Faison Street

should not have the superior fixtures. Nor do the town's criteria

explain why the new (1956) white Barney Chiz horseshoe subdivision

at the southern corporate limits has new mercury vapor fixtures

while the even newer Rebecca Addition (1968) (east of Route 61 in

the northeast corner of the city (Cohea Street)) and Chiz's Silver

Bayou Subdivision (1968)(Kelly, Lipe and Rogers Streets) have bare

33/

bulb fixtures (R. 461, 505).

D. Traffic Control

The defendants did not offer, nor did the district court

refer to any explanation to justify the proven absence of any

traffic control signs in the black neighborhoods in contrast to

the frequent placement of such signs in the white neighborhoods.

E. Sanitary Sewers

The court below found "rational considerations" that justified

the absence of sanitary sewers for almost 20% of the black popula

tion of Shaw. It concluded that:

33/ See Plaintiffs' Exhibit No. 7.

-37-

Part of the problem in reaching

all older unserved areas has been

the necessity for bringing this

service into newer subdivisions

developed for both races and

brought into the town, as it is

the town's firm policy to make

sewer installations for all such

new areas (R. 564),

In the first place, from the record of extensions to the

sanitary sewer system since its completion in 1965 there is no

discernible, no less a "firm", policy of making extension only

to newly developed areas. Instead, the system has been extended

to a greater number of older dwellings than to new ones. The

extensions in 1966-67 in the Promised Land Addition, one of the

town's oldest areas, served approximately 65 old homes while all

of the extensions to nev? areas have served only about 40 new

34/homes. The record shows that when the original sewer system was

15constructed a large part of the black population (over one-third)

was not served. Since its completion, the system has been extended

to some of the areas that were originally unserved as well as some

newly developed areas. But the fact that the new extensions have

benefited black as well as white residents does not excuse the

34/ Extensions of the sanitary sexier system in old neighborhoods

were made to 67 homes in the Promised Land Addition and 5 homes on

Mose and Railroads Avenues in the Gale Street area. Extentions in

newly developed areas were made to 28 homes on Kelly and Lipe

Streets, 4 homes in the Barney Chir* Horseshoe Subdivision, 3 homes

on Dewitt Street and 6 homes on Cohea street (Rebecca Addition)

(R. 207-20S). See Defendants' Exhibit No. 5.

35/ See p. 9, notes 11, 12, above.

-38-

initial neglect of the unserved black neighborhoods. And a "firm

policy" of making installations in new areas which has the effect

of freezing in this inequality is not justified merely because

there has been no racial discrimination in the new extensions.

As this Court has said, "a relationship otherwise rational may

be insufficient in itself to meet constitutional standards — if

its effect is to freeze-in past discrimination." Henry v.

Clarksdale School District. 409 F.2d 682,688 (5th Cir. 1969).

Furthermore, besides the slight indications in the record

that this was in fact defendants' policy (R. 212-13, 394, 396),

defendants never explained why they chose to prefer new residents

or new homes over older neighborhoods that had already been by

passed by the sewer system. Presumably, such a policy is based

upon the town's desire to increase its tax base by encouraging the

construction of new homes which might not be built if the town did

not immediately supply municipal services such as sewers. But

however reasonable such a policy would be in isolation, it cannot

justify the perpetuation of the conditions that were built into

the system by the original failure to serve large black neighbor

hoods. Fiscal considerations alone do not represent a sufficiently

compelling governmental interest to justify the denial of sanitary

sewers to a substantial number of the black residents of Shaw. To

paraphrase what the Supreme Court said in Shapiro v. Thompson. 394

U.S. 618 (1969) about denying welfare benefits to new residents:

-39-

We recognize that a State has a valid

interest in preserving the fiscal

integrity of its programs. It may

legitimately attempt to limit its

expenditures, whether for public

assistance, public education, or any

other program. But a State may not

accomplish such a purpose by invidious

distinctions between classes of its citizens. . . .

[The state] must do more than show

that denying [sanitary sewers] to

[old] residents saves money. The

saving of . . . costs cannot justify

an otherv/ise invidious classification.Id. at 633.

The policy of extending sanitary sewerage facilities to

newly developed areas is even less compelling in light of the

town's enactment in 1967 of an ordinance that requires developers

to provide sewerage lines in their subdivisions (R. 397, 474).

Thus, the major part of the expense of extending sewers to new

areas is borne by the subdivider and not by the town.

The court also concluded that:

While the complaint about less than

100?6 sanitary sewerage for all residences is certainly a real one, that

condition arises basically from the fact

that local law does not yet require indoor

plumbing. The lack of sanitary sewers in

certain areas of the town is not the

result of racial discrimination in with

holding a vital service; rather it is a

consequence of not requiring through a

proper housing code, certain minimal

conditions for inhabited housing (R. 572).

The court apparently overlooked the ordinance of the town

enacted on August 1, 1967 that requires [Section 3] all property

owners whose property is located on a street where a sanitary

-40-

sewerage line has been laid to install indoor plumbing and to

connect it to the sewer line. It also requires [Section 6] such

installation and connection whenever new sewer lines or extensions

36/are provided (R. 485-36). Thus, it is not the absence of a proper

housing code that is responsible for the lack of sanitary sewerage

facilities in the black neighborhoods but rather it is the absence

22/of any sewer lines to which the property owners can connect.

F. Water Supply and Fire Hydrants

Defendants made no attempt to explain or justify the inadequacy

of the town's water distribution system in two of the largest black

neighborhoods in town, the Gale Street area and the Promised Land

Addition. They say only that they are planning to improve the

situation and have applied to the Uhited States Department of

Housing and Urban Development for a grant that would help them do

it (R. 221-22, 308-09). But the promise to remedy the inequalities

brought about by past discrimination does not defeat plaintiffs'

claim or their right to injunctive relief. As one court has said,

"protestations of repentence and reform timed to anticipate or

that "he

36/ A copy of this ordinance, Exhibit D to Defendants' Answers

to the Second Set of Interrogatories was admitted into evidence at

R. 174.

37/ The court stated that the "great majority of the town's Negro

residents is afforded sewerage facilities although many such residences continue without indoor plumbing, not yet required by local

law" (R. 564-65). There is no evidence in the record, however, of

any residence that is not connected to an available sewer main.

On the contrary, the only homes without sanitary sev/erage are un

served because there are no sewer mains on the street. (See R.

207-215)

-41-

blunt the force of a lawsuit offer insufficient assurance" that the

practice sought to be enjoined will not be repeated. Lank ford v.

Gelston, 364 F.2d 197, 203 (4th Cir. 1966).

Nor does the record disclose any justification for the past

and present inferiority of water supply in the black neighborhoods.

Instead, the record reflects an historic neglect of the black

neighborhoods. As with street paving, the town did not provide

water mains to many of the black neighborhoods until the entire

white population had first been served. Every white neighborhood

in town was served after the installation of a main on Jefferson

Boulevard in 1950 (R. 216-17, 510-11). Not until 1957, however,