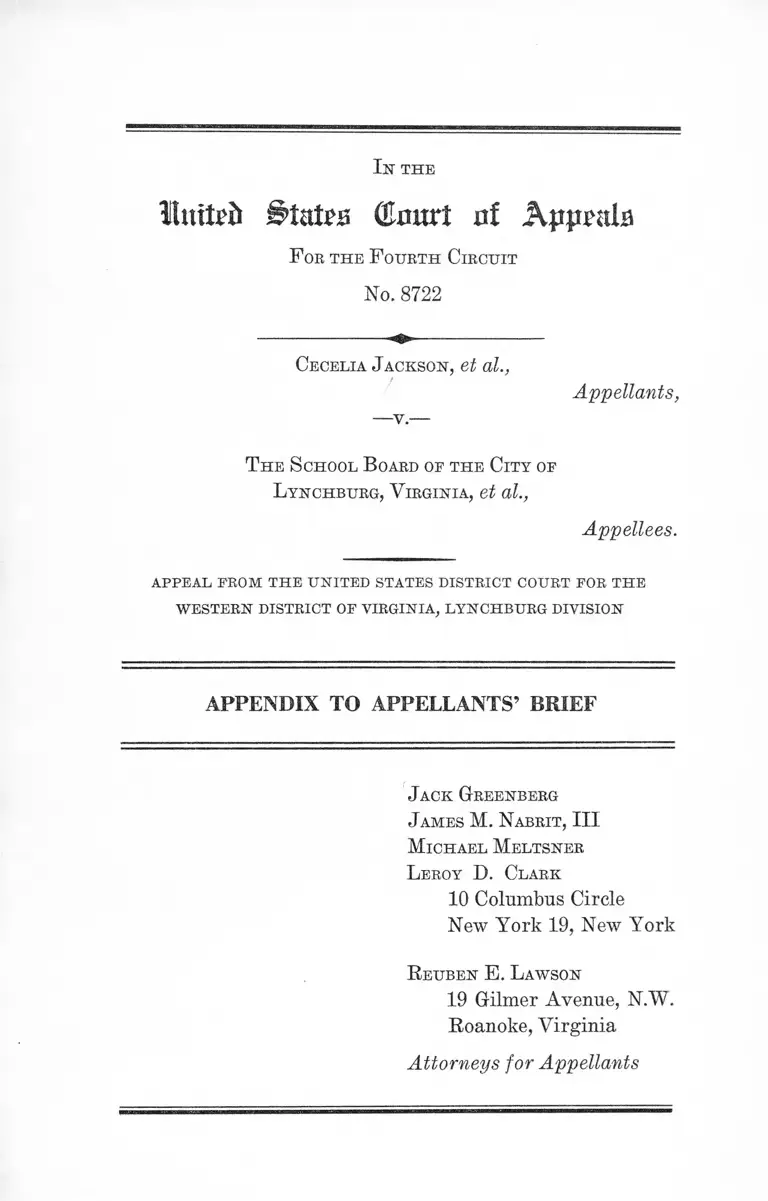

Jackson v. City of Lynchburg, VA School Board Appendix to Appellants' Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jackson v. City of Lynchburg, VA School Board Appendix to Appellants' Brief, 1962. 9b6af7e5-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/54d5153a-0012-46d8-96c7-36afef439b19/jackson-v-city-of-lynchburg-va-school-board-appendix-to-appellants-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I n th e

U m te ft S t a t e s O In u rt o f A p jm i l f l

F ob t h e F o u r th C ir c u it

No. 8722

C ecelia J a ckson , et al.,

Appellants,

T h e S chool B oard of t h e C it y of

L y n c h b u r g , V ir g in ia , et al.,

Appellees.

a p p e a l f r o m t h e u n it e d s t a t e s d is t r ic t c o u r t f o r t h e

WESTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA, LYNCHBURG DIVISION

APPENDIX TO APPELLANTS’ BRIEF

J ack G reen berg

J am es M . N abrit , III

M ic h a e l M e l t sn e r

L eroy D. C lark

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

R e u b e n E. L aw son

19 Gilmer Avenue, N.W.

Roanoke, Virginia

Attorneys for Appellants

INDEX TO APPENDIX

PAGE

Relevant Docket Entries ........................................... la

Complaint .................................................................... 4a

Motion to Dismiss of The School Board ................. 16a

Motion to Dismiss of the Pupil Placement Board .... 17a

Answer of Pupil Placement Board .......................... 18a

Answer of School Board ........................................... 19a

Excerpts From Hearing of November 14, 1961 .......... 24a

Direct Examination of M. L. Carper .............. 24a

Direct Examination of Duncan C. Kennedy....... 32a

Order of November 15,1961 ....................................... 35a

Opinion of January 15, 1962 ................................... 37a

Order of January 25, 1962 ........................................... 56a

Plan for Admission of Pupils to the Schools of the

City of Lynchburg ........ 57a

Resolutions of School Board Annexed to Plan for

Admission........... ..................................................... 58a

Plaintiffs’ Objection to the P lan ................ 60a

11

PAGE

Excerpts From Hearing of March 15, 1962 .............. 65a

Direct Examination of B. C. Baldwin, Jr. ....... 65a.

Cross Examination of B. C. Baldwin, J r ........... 82a

Redirect Examination of B. C. Baldwin, J r ........ 96a

Direct Examination of M. Lester Carper.......... 97a

Cross Examination of M. Lester Carper _____ 105a

Direct Examination of Herman Lee .......... 113a

Cross Examination of Herman Lee ................. 117a

Redirect Examination of Herman Lee .............. 119a

Recross Examination of Herman Lee .............. . 121a

Direct Examination of Duncan C. Kennedy .... 122a

Cross Examination of Duncan C. Kennedy___ 126a

Direct Examination of M. Lester Carper ...... 128a

Opinion of April 10, 1962 ...................... ................ 136a

Order of April 18, 1962 ............................. ............. 150a

Notice of Appeal 152a

Relevant D ocket Entries

9/18/61

10/ 6/61

10/ 7/61

10/ 9/61

11/13/61

11/14/61

11/14/61

11/16/61

Rec’d and filed Complaint. * * * Rec’d and filed

Motion for Interlocutory Injunction.

Rec’d and filed Motion Under Rule 12(b) to

Dismiss Complaint of the defendants, The

School Board of the City of Lynchburg and

M. L. Carper, Superintendent of Schools of the

City of Lynchburg.

Rec’d and filed Motion to Dismiss by the defen

dants, E. J. Oglesby, Alfred L. Wingo and Ed

ward T. Justis, Individually and constituting

the Pupil Placement Board of the Common

wealth of Virginia. . . .

Rec’d and filed Answer of the Pupil Placement

Board.

Rec’d and filed Answer of Defendants, The

School Board of the City of Lynchburg and

M. L. Carper, Superintendent,

Hearing on motion to dismiss complaint, argu

ment thereon, motion denied. # *

Evidence adduced on complaint. No evidence

thereon by defendants. Both parties rested.

Defendants by counsel renewed motion for

School Board and Mr. Carper to be dismissed.

Motion overruled, exception noted. Argument—

Court reserves decision as to 2 pupils but will

admit 2. Directs memoranda submitted within

3 weeks from this date.

Rec’d and entered Order signed by Judge

Michie, November 15, 1961, directing admission

of plaintiffs Cardwell and Woodruff to the 9th

2a

11/27/61

1/16/62

1/25/62

2/24/62

3/12/62

3/15/62

grade at E. C, Glass High School on 1/29/62

and denying prayer of plaintiffs Jackson and

Hughes. Motion for injunction taken under ad

visement. Memoranda to be submitted on or

before 12/5/61.

Rec’d Motion for New Trial on Part of the

Issues with Points and Authorities in Support

of Motion and Certificate of mailing, filed Nov.

25, 1961.

Rec’d and filed Opinion, signed by Thomas J.

Michie, U. S. District Judge, dated January 15,

1962.

Rec’d and entered Order signed by Thomas J.

Michie, IT. S. District Judge, dated Jan. 24, 1962,

ordered the School Board of the City of Lynch

burg to present to the Court within thirty (30)

days from this date a plan for admission of

pupils to the schools of the City without regard

to race and the entry of a more general injunc

tion herein will be deferred until such plan has

been presented.

Plan for Admission of Pupils to the Schools of

the City of Lynchburg; Certificate of Service

and Certificate of School Board of Lynchburg

attached.

Filed Plaintiffs’ Objections to Plan filed by

School Board of the City of Lynchburg.

Hearing before Judge Thomas J. Michie in open

Court on Presentation by School Board of Plan

for Admission of Pupils to Lynchburg City

Schools. . . . Defendants introduced evidence in

Relevant Docket Entries

3a

support of plan, witnesses were examined by

counsel for plaintiffs, and Judge Miehie retired

into chambers with counsel for arguments on

plan. Order to be submitted at a later date.

3/15/62 Motion of Defendants to Approve Public School

Assignment Plan for the City of Lynchburg.

4/11/62 Rec’d and filed Opinion, signed by Thomas J.

Miehie, U. S. District Judge, dated April 10,

1962, approving the plan by the School Board

for the desegregation of the Lynchburg schools.

4/20/62 Rec’d and entered Order signed by Judge Miehie,

April 18, 1962, approving the plan of desegre

gation, as modified, in accordance with the

court’s suggestions and the defendant School

Board shall put said plan into effect, etc., said

plan shall not affect the rights of Owen Calvin

Cardwell and Linda Woodruff.

5/ 5/62 Rec’d & Filed Notice of Appeals by the plaintiffs

from the Order approving the defendants’ plan

of desegregation (and thereby denying part of

the injunctive relief prayed by plaintiffs), en

tered April 18, 1962.

Relevant Docket Entries

4a

Bill of Complaint

(Filed: September 18, 1961)

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F oe t h e W e ster n D istr ic t of V ir g in ia

L y n c h b u r g D iv isio n

Civil Action Number 534

C ecelia J a ck so n , an infant by George F. Jackson, her

father and next friend,

L in d a W oo d ru ff , an infant by Edward M. Barksdale and

Georgia W. Barksdale, her stepfather and mother and

next friend,

O w e n C. C ardw ell , J r ., an infant b y Owen C. Cardwell,

his father and next friend,

B renda E. H u g h e s , an infant by Mabel Hughes, her mother

and next friend,

and

G eorge F. J a ck so n , E dward M. B arksdale, G eorgia W.

B arksdale , O w e n C. Cardw ell a n d M abel H u g h e s ,

Plaintiffs,

T h e S chool B oard of t h e C ity of L y n c h b u r g , V ir g in ia ,

M. L. C a rper , Superintendent of Schools of the City of

Lynchburg, Virginia,

and

E. J. O glesby , A lfred L. W ingo and E dward T. J u s t is ,

individually and constituting the P u p il P l a c em en t

B oard of the Commonwealth of Virginia,

Defendants.

I

1. (a) Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under Title

28, United States Code, Section 1331. This action arises

5a

under Article 1, Section 8, and the Fourteenth Amendment

of the Constitution of the United States, Section 1, and

under the Act of Congress, Revised Statutes, Section 1977,

derived from the Act of May 31, 1870, Chapter 114, Section

16,16 Stat. 144 (Title 42, United States Code, Section 1981),

as hereafter more fully appears. The matter in contro

versy, exclusive of interest and cost, exceeds the sum of Ten

Thousand Dollars ($10,000.00).

(b) Jurisdiction is further invoked under Title 28, United

States Code, Section 1343. This action is authorized by the

Act of Congress, revised Statutes, Section 1979, derived

from the Act of April 20, 1871, Chapter 22, Section 1, 17

Stat. 13 (Title 42, United States Code, Section 1983), to be

commenced by any citizen of the United States or other per

son within the jurisdiction thereof to redress the depriva

tion under color of state law, statute, ordinance, regulation,

custom or usage of rights, privileges and immunities

secured by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States and by the Act of Congress, Revised

Statutes, Section 1977, derived from the Act of May 31,

1870, Chapter 114, Section 16, 16 Stat. 144 (Title 42, United

States Code, Section 1981), providing for the equal rights

of citizens and of all persons within the jurisdiction of the

United States as hereafter more fully appears.

II

2. Infant plaintiffs are Negroes, are citizens of the United

States and of the Commonwealth of Virginia, and are resi

dents of and domiciled in the political subdivision of Vir

ginia for which the defendant school board maintains and

operates public schools. Said infants are within the age

limits of eligibility to attend, and possess all qualifications

Bill of Complaint

6a

and satisfy all requirements for admission to, said public

schools.

3. Adult plaintiffs are Negroes, are citizens of the United

States and of the Commonwealth of Virginia, and are resi

dents of and domiciled in said political subdivision. They

are parents or guardians or persons standing in loco

parentis of one or more of the infant plaintiffs.

4. Plaintiffs bring this action in their own behalf and,

there being common questions of law and fact affecting

the rights of all Negro children attending public schools in

the Commonwealth of Virginia and, particularly, in the

said political subdivision, and the parents and guardians

of such children, similarly situated and affected with refer

ence to the matters here involved, who are so numerous

as to make it impracticable to bring all before the court, and

a common relief being sought, as will hereinafter more fully

appear, the plaintiffs also bring this action, pursuant to

Rule 23(a) of the Federal Rule of Civil Procedure, as a

class action on behalf of all other Negro children attending

public schools in the Commonwealth of Virginia and, par

ticularly, in said political subdivision, and the parents and

guardians of such children, similarly situated and affected

with reference to the matters here involved.

I l l

5. The Commonwealth of Virginia has declared public

education a state function. The Constitution of Virginia,

Article IX, Section 129, provides:

“Free schools to be maintained. The General As

sembly shall establish and maintain an efficient system

of public free schools throughout the State.”

Bill of Complaint

7a

Pursuant to this mandate, the General Assembly of Virginia

has established a system of public free schools in the Com

monwealth of Virginia according to a plan set out in Title

22, Chapters 1 to 15, inclusive, of the Code of Virginia, 1950.

The establishment, maintenance and administration of the

public school system of Virginia is vested in a State Board

of Education, a Superintendent of Public Instruction, Divi

sion Superintendent of Schools, and County, City and Town

School Boards (Constitution of Virginia, Article IX, Sec

tions 130-133; Code of Virginia, 1950, Title 22, Chapter 1,

Section 22-2).

IV

6. The defendant school board, the corporate name of

which is stated in the caption, exists pursuant to the Con

stitution and laws of the Commonwealth of Virginia as an

administrative department of the Commonwealth, discharg

ing governmental functions, and is declared by law to be

a body corporate. Said school board is empowered and

required to establish, maintain, control and supervise an

efficient system of public free schools in said political sub

division, to provide suitable and proper school buildings,

furniture and equipment, and to maintain, manage and

control the same, to determine the studies to be pursued

and the methods of teaching, to make local regulations for

the conduct of the schools and for the proper discipline of

the students, to employ teachers, to provide for the trans

portation of pupils, to enforce the school laws, and to per

form numerous other duties, activities and functions essen

tial to the establishment, maintenance and operation of

the public free schools in said political subdivision. (Con

stitution of Virginia, Article IX, Section 133. Code of Vir

ginia, 1950, as amended, Title 22.)

Bill of Complaint

8a

7. The defendant division superintendent of schools,

whose name as such officer is stated in the caption, holds

office pursuant to the Constitution and laws of the Common

wealth of Virginia as an administrative officer of the public

free school system of Virginia. (Constitution of Virginia,

Article IX, Section 133. Code of Virginia, 1950, as

amended, Title 22.) He is under the authority, supervision

and control of, and acts pursuant to the orders, policies,

practices, customs and usages of the defendant school board.

He is made a defendant herein in his official capacity.

V

8. A Virginia statute, first enacted as Chapter 70 of the

Acts of the 1956 Extra Session of the General Assembly,

viz, Article 1.1 of Chapter 12 of Title 22 (Sections 22-231.1

through 22-232.17) of the Code of Virginia, 1950, as

amended, confers or purports to confer upon the Pupil

Placement Board all power of enrollment or placement of

pupils in the public schools in Virginia and to charge said

Pupil Placement Board to perform numerous duties, activi

ties and functions pertaining to the enrollment or place

ment of pupils in, and the determination of school atten

dance district for, such public schools, except in those

counties, cities or towns which elect to be bound by the

provisions of Article 1.2 of Chapter 12 of Title 22 (Sections

22-232.18 through 22-232.31) of the Code of Virginia, 1950,

as amended. (Section 22-232.30 of the Code of Virginia,

1950, as amended.) The names of the individual members

of the Pupil Placement Board are stated in the cajjtion.

9. Said statute provides that each school child who has

heretofore attended a public school and who has not moved

from the. county, city or town in which he resided while

Bill of Complaint

9a

attending said school shall attend the same school which

he last attended until graduation therefrom unless enrolled,

for good cause shown, in a different school by the Pupil

Placement Board. The purposes and effect of said provi

sion are to continue, in general, the discriminatory effect of

the pre-existing requirement of the Commonwealth of Vir

ginia that children in public schools be segregated on the

basis of race and, also, to prevent local school authorities

from devoting efforts toward initiating desegregation and

bringing about the elimination of racial discrimination in

the public school system and from making any prompt and

reasonable start toward full compliance with the May 17,

1954, decision of the Supreme Court inBrown v. Board

of Education.

10. Said statute further provides that any child who

desires to enter a public school for the first time and any

child who is graduated from one school to another within

a school division or who transfers to or within a school

division, or any child who desires to enter a public school

after the opening of the session, shall apply to the Pupil

Placement Board for enrollment and shall be enrolled in

such school as said Board deems proper. The purpose of

this provision, the practice thereunder, and the effect there

of are and have been that throughout the State of Virginia,

and particularly in the political subdivision hereinabove

mentioned, all white children are and have been assigned

to schools generally known and considered as schools for

white children; and Negro children, with few exceptions,

if anjq have been assigned to and placed in schools which

no white children attend.

11. The statute further provides that the parents or

guardians, if aggrieved by action of the Pupil Placement

Bill of Complaint

10a

Bill of Complaint

Board in enrolling their child in a public school, may file

with the Board a protest in writing within fifteen days

after the placement of such child; whereupon the Board will

hold or cause to be held a hearing after publishing notice

thereof once a week for two successive weeks in a news

paper of general circulation in the city or county wherein

the aggrieved party or parties reside. The calculated effect

of such publication in the cases of parents who seek for

their child or children the right to attend public school on

a racially nondiscriminatory basis is to call the attention

of the community to the dissidence of the Negro parents

who seek for their child a racially nonsegregated public

school education and thus to subject that parent to such

pressures which may be brought to induce abandonment of

a federally protected right. Another practice of the Board

in acting upon the protest is to require both parents and

the child to appear before the Board, often at a place dis

tant from their home and usually at considerable expense;

such practice being calculated to induce the parents to

forego their child’s federally protected right to a racially

nonsegregated public school education. Furthermore, the

Board’s original denial of the application for transfer usu

ally comes at such time that, after the subsequent protest

and hearing and action by the Board thereon, judicial

remedy effective at the commencement of the next school

term is forestalled.

VI

12. As matters of routine, every white child entering

school for the first time is initially assigned to and placed

in a school which predominantly, if not exclusively, is at

tended by white children; or if otherwise assigned, then,

upon request of the parents or guardians, such child is

11a

transferred to a school which, being attended exclusively or

predominantly by white children, is considered as a school

for white children. Upon graduation from elementary

school, every white child is routinely assigned to a high

school or junior high school which is predominantly, if not

exclusively, attended by white children. Similarly, and

with few if any exceptions, Negro children entering school

for the first time are initially assigned to a school which

none but Negroes attend and upon their graduation from

elementary school they are routinely assigned to a high

school or to a junior high school which none but Negroes

attend. Thus, in the free public schools of the Common

wealth of Virginia, and particularly in the schools main

tained and operated by the defendant school board, the

pre-existing pattern of racial segregation in public schools

continues unaffected.

12A. The defendant School Board maintains overlapping

school zones, in that all white high school pupils, regard

less of their place of residence attend E. C. Glass High

School (the only high school for white pupils), and all

Negro pupils attend Dunbar High School (the only high

school for Negroes).

13. To avoid the discriminatory result of the practice

described in the paragraph next preceding, the Negro child,

or his parent or guardian from him, is required to make

application for transfer from the school which none but

Negroes attend to a school specifically named. In acting

upon such application for transfer from the all-Negro

school, the defendants take in consideration certain criteria

which defendants do not consider when making initial en

rollments or placements in any school other than the initial

Bill of Complaint

12a

placement or enrollment of a Negro child in a school which

white children attend. If such criteria are not met, the

application for transfer is denied. For example, if the

home of the applicant is closer to the school to which he has

been assigned than to the school to which transfer is sought,

the application is denied notwithstanding the fact that the

latter school is attended by white children similarly situ

ated with respect to residence. For further example, if

intelligence, achievement or other standardized test scores

or other academic records of the applicant do not compare

favorably with the best or the better of similar scores or

records of children attending or assigned to the school

which the applicant seeks to attend, the application is

denied notwithstanding the fact that many white children

attending said school have lower scores or lower academic

records than the applicant has.

YII

14. The defendants have not devoted efforts toward ini

tiating nonsegregation and bringing about the elimination

of racial discrimination in the public school system, neither

have they made a reasonable start to effectuate a transition

to a racially nondiscriminatory system, as under paramount

law it is their duty to do. Deliberately and purposefully,

and solely because of race, the defendants continue to re

quire all Negro public school children to attend school were

none but Negroes are enrolled and to require all white

public school children to attend school where no Negroes

are enrolled.

15. Each infant plaintiff has made timely application

to the defendants for admission to a public school in said

political subdivision heretofore and now maintained for

and attended predominantly, if not exclusively, by white

Bill of Complaint

13a

persons; but the defendants, acting pursuant to a policy,

practice, custom and usage of segregating school children

on the basis of race and color, have denied the application

of each of said infant plaintiffs solely on account of their

race and color.

15A. Each of the plaintiffs herein has made due and

timely application to the Pupil Placement Board for ad

mission to E. C. Glass High School (the white high school)

and upon being denied admission, pursued his wholly in

adequate remedy of appealing to the Pupil Placement

Board. Each plaintiff’s request was again denied and no

reason was given for said denial by the Pupil Placement

Board except to say . . . “was denied because it is the ojjin-

ion of this Board that its previous action was correct.”

16. The refusal of the defendants to grant the application

of each of the plaintiffs for enrollment as requested con

stitutes a deprivation of liberty without due process of law

and a denial of the equal protection of the laws secured

by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States, and a denial of rights secured by Title 42,

United States Code, Section 1981.

17. Plaintiffs and those similarly situated and affected

are suffering irreparable injury and are threatened with

irreparable injury in the future by reason of the policy,

practice, custom and usage and the actions of the defen

dants herein complained of. They have no plain, adequate

or complete remedy to redress the wrongs and illegal acts

herein complained of other than this complaint for an in

junction. Any other remedy to which plaintiffs and those

similarly situated could be remitted would be attended by

such uncertainties and delays as would deny substantial

Bill of Complaint

14a

relief, would involve a multiplicity of suits, and would

cause further irreparable injury and occasion damage,

vexation and inconvenience.

Bill of Complaint

VIII

W h e r e f o r e , plaintiffs respectfully pray:

(A) That this Court enter an interlocutory and a per

manent injunction restraining and enjoining defendants,

and each of them, their successors in office, and their agents

and employees, forthwith from denying infant plaintiffs, or

either of them, solely on account of race or color, the right

to be enrolled in, to attend and to be educated in, the public

schools to which they, respectively, have sought admission;

(B) That this Court enter a permanent injunction re

straining and enjoining defendants, and each of them, their

successors in office, and their agents and employees from

any and all action that regulates or affects, on the basis

of race or color, the initial assignment, the placement, the

transfer, the admission, the enrollment or the education of

any child to and in any public school;

(C) That, specifically, the defendants and each of them,

their successors in office, and their agents and employees

be permanently enjoined and restrained from denying the

application of any Negro child for assignment in or trans

fer to any public school attended by white children when

such denial is based solely upon requirements or criteria

which do not operate to exclude white children from said

school;

(D) That the defendants be required to submit to the

Court a plan to achieve a system of determining initial

assignments, placements or enrollments of children to and

15a

in the public schools on a non-racial basis and be required

to make periodical reports to the Court of their progress in

effectuating a transition to a racially non-discriminatory

school system; and that during the period of such transi

tion the Court retain jurisdiction of this case;

(E) That defendants pay to plaintiffs the costs of this

action and attorney’s fees in such amount as to the Court

may appear reasonable and proper; and

(F) That plaintiffs have such other and further relief

as is just.

Bill of Complaint

16a

The defendants, The School Board of the City of Lynch

burg, and M. L. Carper, Superintendent of Schools of the

City of Lynchburg, by counsel, move the court under Buie

12(b) of the Buies of Civil Procedure to dismiss the bill

of complaint filed against them by the plaintiffs on the fol

lowing grounds:

1. That the bill of complaint fails to state a claim upon

which relief can be granted;

2. The purpose of the bill of complaint is to obtain the

entry of an order which will enjoin and restrain the en

forcement, operation and execution of the Pupil Placement

Act, by restraining the action of officers of the State of

Virginia in the enforcement and execution of the statute,

and of an order or orders made by an administrative board

or commission acting under such statute, upon the ground

of the unconstitutionality of the statute; and under the

provisions of Title 28 U. S. C. A., Section 2281, such an

injunction cannot be granted by any district court or judge

thereof unless the application thereof is heard and deter

mined by a district court of three judges under Title 28,

IT. S. C. A., section 2284;

3. The validity of sec. 22-231.1 Through sec. 22-232.17

of the Code of Virginia, as amended by chapter 500 of the

Acts of Assembly of 1958, known as the Pupil Placement

Act, should first be determined by the Supreme Court of

Appeals of Virginia; and

4. These defendants are improperly joined as parties

defendant as no actual controversy exists between the

plaintiffs and these defendants.

Motion to Dismiss o f The School Board

(Filed: October 6,1961)

17a

Now come the defendants, E. J. Oglesby, Alfred L. Wingo

and Edward T. Justis, individually and constituting the

Pupil Placement Board of the Commonwealth of Virginia,

and respectfully move the Court to dismiss the complaint

herein upon the following grounds:

1— The Bill of Complaint fails to state a claim upon

which relief can be granted.

2— The relief prayed for in general terms has already

been adjudicated.

3— Any specific relief sought by the plaintiff’s is as indi

viduals and not as a class, and no specific violation of any

such individual rights is alleged.

4— To the exent by implication or inference therefrom

that the Bill of Complaint seeks to obtain the entry of an

order which will enjoin and restrain the enforcement, oper

ation and execution of the Pupil Placement Act, by re

straining the action of officers of the Commonwealth of

Virginia in the enforcement and execution of the statute,

and of an order or orders made by an administrative board

or commission acting under such statute upon the grounds

of the unconstitutionality of the statute, cannot be con

sidered or granted by any single District Court or Judge

thereof, but only if at all, upon application to and hearing

and determination by a District Court of three Judges.

5— Even so, the validity and constitutionality of the Pupil

Placement Act, if drawn into question, should first be de

termined by the Supreme Court of Appeals of the Common

wealth of Virginia.

Motion to Dismiss o f the Pupil Placem ent Board

(Filed: October 7,1961)

18a

Not waiving but expressly reserving and relying in the

first instance on their Motion to Dismiss—now, moreover,

for their joint and several answer to the complaint in these

proceedings in so far as advised material and proper, the

defendants E. J. Oglesby, Alfred L. Wingo and Edward

T. Justis, say:

1— The existence of the School Board of the City of

Lynchburg, Virginia, the further fact that M. L. Carper is

the Division Superintendent of Schools, and the further

fact that these defendants constitute the Pupil Placement

Board of the Commonwealth of Virginia, is all admitted.

2— All of the other allegations of the complaint are

denied or strict proof thereof is called for, or constitute a

recital of laws and legal conclusions as to which no answer

is required.

Answer o f the Pupil Placem ent Board

(Filed: October7,1961)

19a

Answer of Defendants, the School Board of the City of

Lynchburg and M. L. Carper, Superintendent of

Schools of the City of Lynchburg to Bill of Complaint

Reserving Motion to Dismiss the Rill of Complaint

(Filed: October 9,1961)

The defendants, the School Board of the City of Lynch

burg, Virginia, and M. L. Carper, Superintendent of Schools

of the City of Lynchburg, Virginia, reserving and without

waiving their motion to dismiss the bill of complaint here

tofore filed in this action, for their joint and several an

swers to the bill of complaint, answer and say:

1. Strict proof of all of the allegations of jurisdiction

set out in paragraphs 1 and 2 of the bill of complaint is

called for. These defendants deny that any action of theirs

or either of them have deprived the plaintiffs or any of

them of any right, privilege or immunity secured by the

Constitution of the United States or any amendment thereto

or any act of congress.

2. These defendants are without full knowledge or in

formation sufficient to form a belief as to the truth of the

allegations contained in paragraphs 2 and 3 of the bill of

complaint.

3. With regard to the allegations of paragraph 4 of the

bill of complaint, these defendants deny that there are com

mon questions of law and fact affecting the rights of all

Negro children attending public schools in the Common

wealth of Virginia or within the City of Lynchburg and that

therefore the plaintiffs cannot maintain a class action.

4. The allegations of paragraph 5 of the bill of com

plaint are admitted except that these defendants allege that

the enrollment or placement of pupils in, and the determina

20a

tion of school attendance districts for the public schools of

Virginia, including those in the City of Lynchburg, is law

fully vested in the Pupil Placement Board of the Common

wealth of Virginia under Article 1.1 of Chapter 12 of Title

22 (Section 22-232.1 through 22-232.17) of the Code of

Virginia, 1950 as amended.

5. The allegations of paragraph 6 are admitted, except,

however, these defendants allege that the enrollment and

placement of pupils, under their general supervision in

the City of Lynchburg is lawfully vested in the Pupil Place

ment Board of the Commonwealth of Virginia as herein

before set out.

6. The allegations of the first sentence of paragraph 7

of the bill of complaint are admitted. As to the allegations

contained in the second sentence of said paragraph, these

defendants allege that pursuant to Section 22-36 of the Code

of Virginia, 1950 as amended, the powers and duties of the

division superintendents is fixed by the State Board of

Education of the Commonwealth of Virginia.

7. The allegations of paragraph 8 exclusive of the im

plications arising from the use of the words “or purports to

confer” are admitted.

8. The allegations of the first sentence of paragraph 9

of the bill of complaint are admitted, but the plaintiffs’

conclusions as stated in the second sentence thereof are

denied.

9. The allegations of the first sentence of paragraph 10

of the bill of complaint are admitted but the plaintiffs’ con

clusions as stated in the second sentence thereof are denied.

Answer of the School Board of the City

of Lynchburg, Etc.

21a

10. The allegations of the first sentence of paragraph 11

of the bill of complaint are admitted but the plaintiffs’

conclusions and other allegations contained in the balance

of said paragraph 11 are denied.

11. These defendants are without full knowledge or in

formation to form a belief as to the truth of the allega

tions contained in paragraph 12 of the bill of complaint in

that the assignment and placement of pupils in the public

school system of the Commonwealth of Virginia, and par

ticularly in the City of Lynchburg is lawfully under the

direction and control of the Pupil Placement Board of the

Commonwealth of Virginia, and not these defendants.

12. With regard to the allegations of paragraph 12A.

of the bill of complaint, these defendants state that at the

present time the defendant school board of the City of

Lynchburg operates two public high schools; namely,

E. C. Glass High School and Dunbar High School; that at

the present time all students at E. C. Glass High School are

of the White race and that all students at the Dunbar

High School are of the Negro race; and that with the ex

ception of the applications of the plaintiffs in this case,

no applications for transfer from one high school to the

other are pending.

13. As the placement and assignment of pupils in the

public school system of the Commonwealth of Virginia, is,

insofar as these defendants are concerned, lodged exclu

sively with the Pupil Placement Board of the Common

wealth of Virginia, these defendants are without full knowl

edge or information to form a belief as to the truth of the

Answer of the School Board of the City

of Lynchburg, Etc.

22a

allegations contained in paragraph 13 of the bill of com

plaint.

14. For answer to the allegations contained in the first

sentence of paragraph 14 these defendants allege that under

valid laws of the Commonwealth of Virginia, (i.e., Sections

22-232.1 through 22-232.17 of the Code of Virginia, 1950

as amended) the assignment and placement of all pupils

in the public school system in the City of Lynchburg, is,

at the present time, under the exclusive control of the Pupil

Placement Board of the Commonwealth of Virginia and that

these defendants have no obligation, authority or duty with

regard to the assignment or placement of pupils. The allega

tions set out in the second sentence of paragraph 14 of the

bill of complaint are denied.

15. These defendants admit as alleged in paragraph 15

of the bill of complaint that the infant plaintiffs applied

for and were denied admission to certain public schools

in the City of Lynchburg, but these defendants specifically

deny the plaintiffs’ conclusion that the applications were

denied for the reasons stated in said paragraph 15.

16. These defendants admit that the plaintiffs have made

application to the Pupil Placement Board for admission to

E. C. Glass High School as alleged in paragraph 15A. of the

bill of complaint. All conclusions and other statements con

tained in said paragraph 15A. are denied.

17. These defendants deny the allegations contained in

paragraphs 16 and 17 of the bill of complaint.

Answer of the School Board of the City

of Lynchburg, Etc.

23a

F u r t h e r a n s w e r in g :

These defendants make the following allegations of fact:

18. That for a long period of time the School Board

of the City of Lynchburg has devoted itself to the providing

of a good and proper education for all children in the pub

lic school system of the City, without discrimination as to

race or color; that it has devoted itself to the maintenance

of good race relationships in the public school system; and

in that connection has desegregated teachers’ meetings, staff

meetings and all professional study meetings; that at no

time has the School Board of the City of Lynchburg or the

Superintendent of the Lynchburg City School System

adopted any policy by resolution or otherwise requiring the

continued segregation of races in the Lynchburg public

schools; that these defendants are advised and, therefore,

allege that Sections 22-232.1 through 22-232.17 of the Code

of Virginia, 1950 as amended, generally known as the Pupil

Placement Act, is a valid and constitutional law providing

for the assignment and placement of pupils in the public

schools in the City of Lynchburg and that these defendants

cannot be held accountable for any alleged acts of dis

crimination charged by the plaintiffs in this suit, and that

therefore no actual controversy exists betw'een the plaintiffs

and these defendants.

Answer of the School Board of the City

of Lynchburg, Etc.

24a

Excerpts From Hearing November 14, 1961

E v id en ce I ntroduced on B e h a l f of t h e P l a in t if f s

The witness, M. L. C a rper , called as an adverse witness

on behalf of the plaintiffs, on examination testified, as fol

lows:

Direct Examination by Mr. Nabrit:

Q. Mr. Carper, you are the Superintendent of Schools of

the city of Lynchburg and have been such since July, 1961?

A. Since July the 1st, 1961.

Q. I will ask you briefly about basic facts of the school

system. Is it true you have twenty-three elementary

schools in the system and that five of those schools are

attended by only Negro and the rest by only white pupils?

A., That’s correct.

Q. Those schools were Negro and have all Negro

teachers and staffs and so forth? A. Those schools have

all Negro pupils and Negro staffs.

Q. Is it true that the schools with white pupils have all

white teachers? A. Yes.

Q. Is it true you have 11,750 pupils in the school system?

—9—

A. True.

Q. And about one-fourth of that number are Negroes

and slightly less than a fourth? A. Approximately.

Q. Is it also true you have two high schools, one called

E. C. Glass High School, which is attended only by white

pupils? A. Yes.

# # * # #

— 10—

Q. You have one all Negro high school called Dunbar, is

that right? A. Yes.

—8—

25a

Q. Now, is it also true that your elementary schools in

the city have attendance areas or zones they serve? A.

Yes.

Q. And that you have separate zones for colored and

white elementary schools? A. Yes, sir.

Q. The colored elementary schools, the areas they serve,

overlap the areas of some of the white schools? A. Yes.

Q. And so what you have is two sets of zones, one set

of zones for Negro elementary pupils and another for white

elementary pupils? A. Yes.

Q. This system has been used here in Lynchburg for

some time? A. Insofar as I can determine it has been the

custom throughout the years.

■u. 'V- .y . -y. -y.W W -ft-

—13—

# # # * *

Q. In Lynchburg when a child finishes—a white child

finishes elementary school, the school is placed on his form

by the principal and is always E. C. Glass? A. Correct.

Q. And when a Negro child finishes elementary school,

the school placed on his form is always Dunbar? A. Cor

rect. I beg your pardon. When a white elementary child

completes elementary school, he goes to Robert E. Lee,

which is the eighth grade.

Q. You have all the eighth grade at Robert E. Lee? A.

All eighth grade white children at Robert E. Lee, yes, sir.

Q. You have no comparable eighth grade school for

- 1 4 -

Negroes? A. No.

Q. Negroes in Lynchburg go to high school? A. It is

established on the 7-5 principle. Glass was too crowded to

maintain the eighth grade and it had to be pulled out a

few years back and put in Robert E. Lee. Dunbar is still

M. L. Carper—for Plaintiffs—Direct

26a

capable of accommodating the eighth grade in the 7-5

organization.

Q. When a child finishes the white eighth grade, Robert

E. Lee, he goes through the procedure again? A. Again.

Q. At this time the principal fills out E. C. Glass on his

form ? A. Right.

Q. Now, after the principal signs the form, is it then

sent to your office? A. Sent to my office.

Q. At your office do you routinely sign the forms or does

your secretary do that for you? A. My secretary or I

either one sign the forms.

Q. And does your secretary have a general authorization

to sign them when the principal has made a recommenda

tion? A. Yes.

Q. Now, at this point, such applications are then sent in

—15—

a group with similar applications to the Pupil Placement

Board in Richmond? A. Correct.

Q. How do you send them, by mail with a letter of

transmittal describing the group, what it is? A. So many

are involved we usually take them to Richmond.

Q. You carry them personally? A. In a box in the car,

yes.

Q. And when you get there do you tell Mr. Hilton, the

Executive Secretary, what they are? A. We deliver them

to the office, yes, and tell him what they are.

Q. Now, when you get a group of forms like this, with

your recommendation and the local principal’s recommen

dation on it, are they routinely approved by the Pupil

Placement Board? A. You will have to ask the Pupil

Placement Board that question.

Q. Well, I wasn’t trying to find out from you how they

handle it. What I was trying to find out was the result.

M. L. Carper—-for Plaintiffs—Direct

27a

You get a notice from them as to the result, don’t you? A.

We get a notice back from them of the result.

Q. That notice is this blue copy of the Pupil Placement

- 1 6 -

Form, isn’t it? A. Correct.

Q. Which has on the bottom of it the name of the school,

the name of the city or county, a date stamped and a

stamped signature of C. S. Hilton. That is on all of these

that come back, is it not? A. Correct.

Q. Now, when your local authorities make a recommenda

tion do they always come back approved in accordance with

your recommendation? A. Yes.

Q. Whenever you recommend an assignment in your ex

perience they have approved it. That’s correct, isn’t it?

A. Yes.

Q. Now, this routine we have discussed, this sequence of

events we have been talking about, would this same proce

dure we have discussed also apply to pupils entering the

first grade? A. Yes.

Q. I would gather the parents take their children to the

first grade school in the zone, whether they had some notice,

from you as to what zone they live in. A. I don’t know

how they would be notified heretofore but in general there

are newspaper statements or were this year indicating that

those children would report back to the schools which they

—17—

attended last year or the new children, the first grade or

kindergarten schools, in their general areas. The bound

aries were never defined. We assumed they would know.

Q. In case of doubt, the principal of the elementary

school would know what his boundaries were, wouldn’t he?

A. Eight.

M. L. Carper—for Plaintiffs—Direct

28a

Q. And he would judge whether the child was in his area?

A. Or refer to my office.

Q. Would that same procedure apply when a child moves

from one part of the town—an elementary child moves

from one part of the town to the other? A. Generally,

yes.

Q. By the same procedure, I mean from the local pro

cedure, up through the action by the Pupil Placement

Board. Correct? A. Yes.

Q. Would it be true in elementary school grades you

have almost 100% of the pupils actually now in school in

their zones? A. No.

Q. Would you have categories of exceptions to that?

A. Yes. There are exceptions and mainly because of over-

—18—

crowded conditions in one area and undercrowded in an

other and administrative adjustments are made between

the schools to equalize as far as possible the per pupil ratio

in each school.

Q. Would this be accomplished by transfers of groups of

children in a neighborhood, all the children in such a block

moved to another school? A. That has happened in the

past. However, this year there were some zone lines

changed. In one particular situation I recall we moved an

entire seventh grade and an entire kindergarten from one

compacted school to the other schools that were not com

pacted.

Q. So you have several methods. You can move a class,

a neighborhood or change a zone. A. That’s right.

Q. Other than these adjustments which are accomplished

by your office, would you say the pupils were generally

assigned in accordance with the zones? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Now, would you have individual exceptions to that for

handicapped children or something like that? A. Yes.

M. L. Carper-—for Plaintiffs—Direct

29a

Q. Generally, everybody else is in his zone! A. Bight.

Q. Now, with reference to the two high schools in the

—19—

city. They both serve the whole city. A. Bight.

Q. Glass is city-wide for white pupils and Dunbar is

city-wide for Negro children! A. Yes.

Q. Isn’t it true you have Glass white pupils who live

closer to Dunbar than to Glass! A. Yes.

Q. That would be true of all the white pupils in gener

ally the northeast part of the city, wouldn’t it! A. Yes.

Q. In neighborhoods such as the White Bock Hill area,

Diamond Hill area, Jackson Heights area and areas like

that! A. Yes.

Q. Indeed there are white pupils right in the neighbor

hood of Dunbar, are they not! A. Yes.

Q. And all such pupils are assigned to Glass High

School! A. Yes.

Q. Now, likewise, don’t you have Negro pupils attending

Dunbar who live closer to Glass than to Dunbar! A. Yes.

Q. And can you tell me a couple of neighborhoods where

— 20—

that is true! Would Dearington School be one! A. Dear-

ington would be one.

Q. Can you think of others! A. I don’t have a map be

fore me. I would rather not designate.

Q. Would Fort Hill be one! A. Certain sections of Fort

Hill.

Q. Now, for elementary purposes, is it true that you

have Negroes living in almost all of the white elementary

school zones! A. Not in all but in a great many.

Q. All but a couple! A. All but a few.

# # * # *

M. L. Carper—for Plaintiffs—Direct

30a

M. L. Carper—for Plaintiffs—Direct

— 36—

# * # # #

Q. Now I will ask you about ability grouping in your

schools. Don’t you have children arranged in the schools

and within the grades, or at least in some courses, by

ability and level of advancement! A. In general, yes.

Q. So that, for example, among the first year high school

students who take several courses, such as English or

mathematics, they might be divided up within the class at

Glass or Dunbar as above average students, average stu-

— 37-

dents, lower students or something like that? A. I believe

all of that was testified by Mr. McCue and Mr. Seay. .

By the Court:

Q. Is that the track system? A. No, it is not the track

system. There is some special grouping in certain areas

in mathematics. For instance, they accelerate the more

capable youngsters. Then in English and in sciences, where

there are college-bound youngsters, some of them are

grouped in terms of purpose and ability. No hard and fast

system is used but all are subject to guidance test data

information that we have on them.

By Mr. Nabrit (continuing) :

Q. This is carried on within the school after the pupil

is admitted? A. It may begin before the pupil is admitted

to a particular school. Your summary is more specifically

for guidance in the eighth grade and that information is

transmitted on to the senior high school considerably

earlier than the youngster would attend so it can be care

fully scrutinized. The records and grouping of the young

sters is carefully scrutinized in the areas where they stand

— 38—

the greatest chance of being successful.

31a

Q. Yon have similar but perhaps more simplified ability

grouping in elementary grades! A. Not to such an extent,

no.

Q. But would you have, for example, perhaps three first

grade classes, or two first grade classes within a school

and have the children divided! A. That may prevail in

some schools and not in others. Again we do not determine

this until we understand the child we are working with.

If it seems better to group the child in terms of ability,

it would be done; otherwise, it would not be done.

Q. So that it would be generally fair to say in your

entire system in your educational judgment you think it

is helpful to group by ability and you do it if you think so ?

A. Wherever it seems to the advantage of the individual

pupil. The schools exist for the children and they attempt

to organize it so that they give every individual the great

est opportunity possible.

Q. You don’t have any schools set aside, any whole school

set aside, for smart or average children or below average

children! A. No.

Q. They are all within the schools. The elementary

—3 9 -

schools take whatever pupils are in their zones and that

is what they end up with! A. With certain exceptions.

Q. Have there been additional pupils admitted at Glass

High School say since the beginning of the school year!

Have you had some new pupils come in! A. There are

always transfers out and transfers in. The net picture

gives a smaller enrollment noAV than in September. There

has been a net loss in pupils since then.

Q. It has been the normal in and out! A. Normal in

and out, yes.

Q. Is it customary to use these I.Q. tests and achievement

M. L. Carper—for Plaintiffs—Direct

32a

tests by your local personnel to assist them in guiding the

pupils as to whether they should take college preparatory

courses or not! A. Guidance is the essential function.

Q. That is the main function of these tests in your sys

tem? A. Yes, sir.

Q. They also help you evaluate your program you use?

A. We make very little use of the information, the massed

results. The essential use for the tests is to help the

individual.

* # # # #

—79—

The witness, D u n c a n C. K e n n e d y , being called as an

adverse witness by the plaintiffs, having first been duly

sworn, on examination testified, as follows:

Direct Examination by Mr. Lawson:

Q. Please state for the Court your name, address, offi

cial position with the Lynchburg City School Board. A.

Duncan C. Kennedy, Jr. I live at 1540 Parkland Drive,

—80-

Lynchburg, Virginia. I am Chairman of the Lynchburg

School Board.

Q. How long have you served on the Board? A. A little

over four years.

Q. How long during that time have you been chairman?

A. Since the spring of 1961.

—85—

# # * # #

Q. Now you are familiar, I believe, with 1954 Supreme

Court decision. You have heard about it haven’t you? A.

I have heard about it.

Q. Since that time, what has the School Board done to

Duncan C. Kennedy—for Plaintiffs—Direct

33a

eliminate segregation in its Lynchburg system? A. I don’t

know that we have taken any action.

Q. What action do you contemplate taking right now to

end segregation in the Lynchburg school system? A. I do

not know.

Q. You don’t know. A. I don’t know.

Q. In other words, you have no knowledge of any action

to end segregation in the Lynchburg school system. Is that

what you are telling me ? A. I do not know of any action

we are going to take.

— 86—

Q. As chairman of the School Board, they won’t take

action without your knowledge, will they? A. They

haven’t, no. They have not taken any action.

Q. If any action had been taken you would have knowl

edge of it right ? A. So I understood.

Q. Have you personally made any recommendation to

the Board concerning eliminating segregation in Lynch

burg? A. I have not.

Q. Ho you anticipate making any?' A. Not at this time.

Q. Have you ever made any announcements concerning

elimination of it to the parents, press or anybody else?

A. We have a committee which is studying the question of

presenting the plan for desegregation to the Lynchburg

School Board.

Q. That committee was appointed when? A. It was ap

pointed during the summer of 1961.

Q. Subsequent to the time these applications were re

ceived? A. Yes, sir.

Q. Has that committee made any report back to the

—8 7 -

School Board? A. This present committee has not. We

had a committee first to study the question as to whether

Duncan C. Kennedy—for Plaintiffs—Direct

34a

it was desirable for the School Board to consider a plan.

That committee reported in the affirmative and it was so

approved by the School Board and a second committee was

appointed to actively develop a plan for consideration.

Q. Do yon have any knowledge of the date when that

committee was appointed! The second committee. A.

Sometime around the middle of August.

Q. August 12th or 13th! A. Somewhere around there.

Q. They have not made any report since that time? A.

No, sir.

Q. You have had how many School Board Meetings since

that time? A. Two. Two regular meetings.

Q. This committee is a committee of the School Board;

it is within the School Board. Are you familiar with

whether they are working with the P.T.A.’s and various

other groups who are interested in civic development? A.

1 do not know whether they are working with them at

this time.

Q. Can you tell me whether since the school closing

laws the School Board has made any public announcements

— 88—

to the teachers, to the parents, to the pupils, to the P. T. A.

or to anybody that they would accept and consider or the

State Pupil Placement Board or both would accept Negro

applications to white schools or white applications to Negro

schools? A. I didn’t understand the question.

(The question was read back by the court reporter.)

The Witness: We have made no announcement of that.

Q. Is your committee working with the Pupil Placement

Board to your knowledge? A. They are not to my knowl

edge.

Duncan C. Kennedy—for Plaintiffs—Direct

= * = * * # #

35a

Order

(Dated: November 15,1961)

(Filed: November 16, 1961)

This cause came on to be heard on November 13th and

14th, first upon the motion to dismiss the complaint filed

by E. J. Oglesby, Alfred L. Wingo and Edward T. Justis,

individually and constituting the Pupil Placement Board of

the Commonwealth of Virginia, and the motion to dismiss

the complaint filed by the School Board of the City of

Lynchburg and M. L. Carper, Superintendent of Schools of

the City of Lynchburg, and said motions were fully argued

by counsel for the defendants and the plaintiffs and the

court thereupon declined to grant either of the motions to

dismiss the complaint.

Whereupon the evidence of the complainants was heard

and the defendants at the conclusion of the plaintiffs’ evi

dence stated that they did not wish to present any evidence

other than what had been brought out by the complainants

and by the defendants’ cross-examination of the complain

ants’ witnesses.

And the court being of the opinion that two of the plain

tiffs, to-wit, Owen Calvin Cardwell and Linda Darnell

Woodruff, are entitled as claimed in the complaint to be

admitted to E. C. Glass High School in Lynchburg, Virginia,

but that it would be in the interest of said complainants that

they be not admitted prior to the January break in the

school year, it is therefore

Ordered

that the defendant' School Board of the City of Lynchburg

and the defendant M. L. Carper, Superintendent of the

Schools of Lynchburg, Virginia, do admit the said plain

tiffs to the 9th grade at E. C. Glass High School on Janu

ary 29, 1962.

36a

Order of November 16, 1961

And the court being of the opinion that it will be in the

best interest of the complainants Cecelia Karen Jackson and

Brenda Evora Hughes to remain in the Dunbar High School

in Lynchburg, Virginia, rather than to be transferred to the

E. C. Glass High School, their prayer for assignment to the

E. C. Glass High School is hereby denied.

And the court, not being sufficiently advised of its opin

ion with respect thereto, doth take under further considera

tion the prayer of the complainants that the court enter fur

ther and more general injunctions against the defendants

and counsel for the plaintiffs and the defendants are re

quested to file with the court memoranda in support of their

contentions with respect to said issue on or before December

5, 1961.

The deputy clerk of this court will transmit a certified

copy of this order to Reuben E. Lawson, Esq., 19 Gilmer

Avenue, N. W., Roanoke, Virginia; to James M. Nabrit, III,

Esq., 10 Columbus Circle, New York 19, New York; to S.

Bolling Hobbs, of Caskie, Frost, Davidson & Watts, 925

Church Street, Lynchburg, Virginia; to C. Shepherd Now

lin, Esq., City Attorney, City Hall, Lynchburg, Virginia;

and to A. B. Scott, Esq., of Christian, Marks, Scott and

Spicer, 1309 State-Planters Bank Building, Richmond 19,

Virginia.

Enter:

T hom as J. M ic h ie

United States District Judge.

A True Copy, Teste:

L e ig h B. H a n es , J r ., Cleric,

By: O tw ay P ettic r ew

Deputy Cleric

37a

(Dated: January 15,1962)

(Filed: January 16,1962)

This is a suit brought by four colored children, by their

next friends, and also by the parents, guardians or persons

standing in loco parentis of the infant plaintiffs against

the School Board of the City of Lynchburg, Virginia, M. C.

Carper, Superintendent of Schools of the City, and E. J.

Oglesby, Alfred L. 'Wingo and Edward T. Justis, indi

vidually and constituting the Pupil Placement Board of the

Commonwealth of Virginia. The action was brought not

only on behalf of the plaintiffs but also as a class action on

behalf of all other Negro children attending public schools

in the Commonwealth of Virginia and particularly in the

city of Lynchburg and the parents and guardians of such

children who are similarly situated to the plaintiffs with

reference to the matters involved in the suit.

The complaint makes various allegations as to the Con

stitution and statutes of Virginia relating to public edu

cation, including the creation and duties of the Pupil Place

ment Board and the local school board and superintendent

of schools. It further alleges that the defendants, in assign

ing pupils to schools in Lynchburg, have discriminated

against the plaintiffs and all other Negro children in Lynch

burg in that all Negro children have been assigned to schools

which no white children attend and all white pupils have

been assigned to schools which no Negro children attend.

The complaint contains allegations with respect to the

statutes from which one might infer that the plaintiffs were

claiming that the Pupil Placement Act (Va. Code, §§22-232.1

to 22-232.17) is unconstitutional. However no direct allega

tion to that effect is made and the complaint does allege

that the plaintiffs have complied with the provisions of the

Pupil Placement Act but have been denied relief by the

Opinion

38a

Pupil Placement Board. And the question of the con

stitutionality of the Act is ignored in the pra3̂ er for relief.

The complaint asks for an injunction restraining the

defendants “from denying infant plaintiffs, or either of

them, solely on account of race or color, the right to he en

rolled in, attend and to be educated in, the public schools

to which they, respectively, have sought admission.” And

plaintiffs’ counsel explained in argument that this prayer

for relief should be interpreted as a prayer for an injunction

against the school board ordering the school board to admit

the plaintiffs to the all-white E. C. Glass High School (here

inafter called Glass) for admission to which they had ap

plied. And the court so interprets the prayer, though it

might have been more directly stated.

The complaint also asks for a permanent injunction

against all of the defendants restraining them “from any

and all action that regulates or affects, on the basis of race

or color, the initial assignment, the placement, the transfer,

the admission, the enrollment or the education of any

child to and in any public school”, together with other

prayers to substantially the same effect, and further that

“the defendants be required to submit to the Court a plan

to achieve a system of determining initial assignments,

placements or enrollments of children to and in the public

schools on a non-raeial basis and be required to make pe

riodical reports to the Court of their progress in effectuat

ing a transition to a racially non-discriminatory school

system.” This latter prayer, as applied to the defendant

Pupil Placement Board and its members, obviously asks

that the Pupil Placement Board be required to bring in a

plan of desegregation for the entire state. Counsel for the

plaintiffs, however, stated that they had not intended to

ask for such relief but had intended this particular prayer

for relief to apply only to the Lynchburg School Board

and the Superintendent of Schools of Lynchburg and the

Opinion D ated J anuary 15,1962

39a

court will therefore limit its consideration of this prayer

to those defendants.

A motion for an interlocutory injunction was filed and

heard on September 22,1961. The motion was denied on the

ground that there had been no adequate showing that the

plaintiffs would be irreparably damaged if the entering of

such injunctions as they might be entitled to were deferred

until after a hearing on the merits of the case.

Motions to dismiss the complaint were made by the

defendants, the grounds of which were that the bill of com

plaint attacked the constitutionality of the Pupil Placement

Act and therefore could be heard only bĵ a three-judge court

under Title 28 USCA, sections 2281-2284, and that the

validity of the Virginia Pupil Placement Act should first

be determined by the Supreme Court of Appeals of Virginia

and a motion was also made to dismiss the local school

board and Superintendent of Schools on the ground that

they were not proper parties. In view of the concession of

plaintiffs’ counsel that the constitutionality of the Pupil

Placement Act was not involved in the case and the allega

tions that the plaintiffs had complied with the provisions of

the Act, the motions to dismiss the complaint were overruled

and the motion to dismiss the local defendants was like

wise overruled for reasons which will sufficiently ajjpear in

the following discussion.

The evidence showed in detail the placement system fol

lowed in Lynchburg and, apparently, in all other school

divisions of the state except those which do not work

through the Pupil Placement Board, either because they

are operating under court injunctions which expressly or

impliedly exempt them from so doing or because under

the provisions of section 22-232.30 of the Code of Virginia

they have elected to place all pupils locally rather than

through the Pupil Placement Board.

Opinion Dated January 15,1962

40a

The Pupil Placement Board has a form number 1 desig

nated “Application for Placement of Pupil”. This form

gives certain fundamental data with respect to the pupil

and contains space for a parent’s or guardian’s signature.

At the bottom is a place for certain information to be filled

in by the local school board including a recommendation as

to the school to which the pupil should be assigned. In

Lynchburg all white pupils eligible to enter high school are

tentatively assigned by the several local school officials

to Glass and all colored children to Dunbar High School

(hereinafter called Dunbar). If these assignments are satis

factory to the parents of the child, who are required to

sign the form, the name of the school to which the pupil is

tentatively assigned by the local board is filled in on this

part of the form. If, however, the parents object to the

proposed assignment no recommendation for assignment

is made by the local school board. Thus when the form

reaches the Pupil Placement Board in Richmond the

Board’s clerical employees can ascertain by a quick glance

at the form whether or not there is a dispute between the

pupil’s parents and the local authorities as to the school

in which the pupil should be enrolled.

There are of course thousands of these forms filled out in

a city the size of Lynchburg and they are brought together

and all taken to Richmond and handed in a bundle to the

appropriate personnel of the Pupil Placement Board.

Of course in the vast majority of cases the parents have

been satisfied with the assignments and the individual ap

plications in these cases are never seen by the individual

members of the Pupil Placement Board itself. It adopts a

general resolution assigning all of such pupils en masse

to the schools to which they have been tentatively assigned

by the local school authorities.

Opinion Dated January 15,1962

41a

Thus while the Pupil Placement Board is theoretically

charged by the Pupil Placement Act with the duty of as

signing to the respective public schools of the state all of

the children in the state who desire to enter such schools,

it does not, and obviously could not, in fact consider all of

the many thousand placements involved. It simply rubber

stamps the vast majority which are non-controversial and

acts in effect as an appeal board in those relatively few cases

in which the child’s parents and the local authorities are in

disagreement as to the proper placement.

In the cases in which the child’s parents have not been

satisfied with the assignment that the local school board

wished to make, the applications are individually considered

by the Board. But before acting on such an application the

Pupil Placement Board asks the local school board to

supply it with certain information. This information in

cludes a statement of the distance between the home of

the child and the school which the child wishes to attend

and the distance between the home of the child and the

school to which the local authorities would have recom

mended assignment had not the parents disagreed with such

assignment. It also includes data with respect to the records

of the children on certain achievement tests. In the case of

three of the pupils involved in this case the tests were the

Standard Achievement Test taken by them in the Fifth

G-rade, the California Mental Maturity Test taken by them

in the Seventh Grade and a test designated on the form as

D.A.T., apparently taken in the Eighth Grade and made up

of a number of different parts. In the case of the fourth

applicant the tests used were the same except that ap

parently that applicant had never taken the Standard

Achievement Test.

Upon receipt of this information by the Pupil Placement

Board the results of the tests that had been taken by the

Opinion Dated J anuary 15,1962

42a

applicant are then compared with the results of the same

tests given the other pupils enrolled in the grade with the

applicant at the time the tests were taken, broken down into

groups which roughly would correspond with the average

group in the class, the below average group and the better-

than-average group. And the individual applicant’s results

are then also compared with the averages on the same tests

of the children in the same grades in the school the applicant

seeks to enter, again roughly divided into the average group,

the below average group and the better-than-average group.

In actually making the assignments the Chairman of the

Board testified that the Board used only two criteria, first,

distances between the child’s home and the two schools and

second, aptitude as determined by the above mentioned

comparisons of test results. If the child lives at a greater

distance from the school he wishes to attend than the school

the school board would prefer to assign him to, he would be

assigned by the Pupil Placement Board to the school to

which the local board wished to assign him. And likewise if

the results of the aptitude tests showed that the child would

be in the below average group in the grade in the school to

which he wanted to transfer, and substantially so, so that

there would be real danger of his failing in that school,

he would be denied the transfer sought even though he

might live nearer to the school to which he wished to trans

fer than to the school to which the local authorities wished to

assign him. If the child lived nearer to the school to which

he wished to go than to the school to which the local au

thorities wished to assign him and if it appeared from the

test results that he would do reasonably well in the school

to which he wished to go he would be assigned to that school.

In the case at bar all four of the applicants were denied

transfer on the ground that they lived nearer to Dunbar

Opinion Dated January 15,1962

43a

than to Glass and two of them were also denied transfer

because of “lack of academic qualifications.”

It was testified that the present Pupil Placement Board

had, sinee the present members took office, assigned several

hundred Negro students to white schools in the state and

had denied transfers to a number of white students seeking

transfer from one white school to another on the same bases

that it had used in denying the transfers of the colored

children involved in this case. There is no evidence to

indicate that the Pupil Placement Board in its actions has

been swayed in any way in making the relatively few assign

ments that it has made (aside from the wholesale ratification

of the assignments agreed upon by the local boards and

the childrens’ parents) by any consideration of race. It

has apparently applied its rigid formulae of distance and

academic qualifications in the same manner to requests for

transfers made by both colored and white children.

And of course the court recognizes the applicability and

desirability of geographical or location or distance tests in

many, perhaps most, plans of school assignment. The loca

tion of the child with respect to the school is perhaps the

simplest and also one of the most important of all of the

criteria which have been considered in the various plans

that have been adopted. But to be valid the criterion of

location or distance must be applied alike to colored and

white children and cannot be used as an excuse for keeping-

certain colored children out of white schools when white

children living in the same vicinity as such colored children

are assigned to those same white schools.*

* Nor does it follow that, if a plan of desegregation based on geographical

considerations is adopted, all children in each geographical area must neces

sarily go to the school in that area to which those children are initially assigned.

Most such plans provide for applications for transfers to other schools for a

variety of reasons. The highly successful Louisville plan—one of the earliest—

which was devised and put into offect by Omer Carmichael, a former superin

Opinion Dated January 15,1962

44a

The difficulty here comes not, however, from discrimina

tory application by the Pupil Placement Board of its rather