Cuthbertson v. Biggers Brothers, Inc. Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1983

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Cuthbertson v. Biggers Brothers, Inc. Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, 1983. 7123d0d9-ae9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/54fd1cb9-c784-4fcf-a5e6-8926702452cb/cuthbertson-v-biggers-brothers-inc-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-fourth-circuit. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

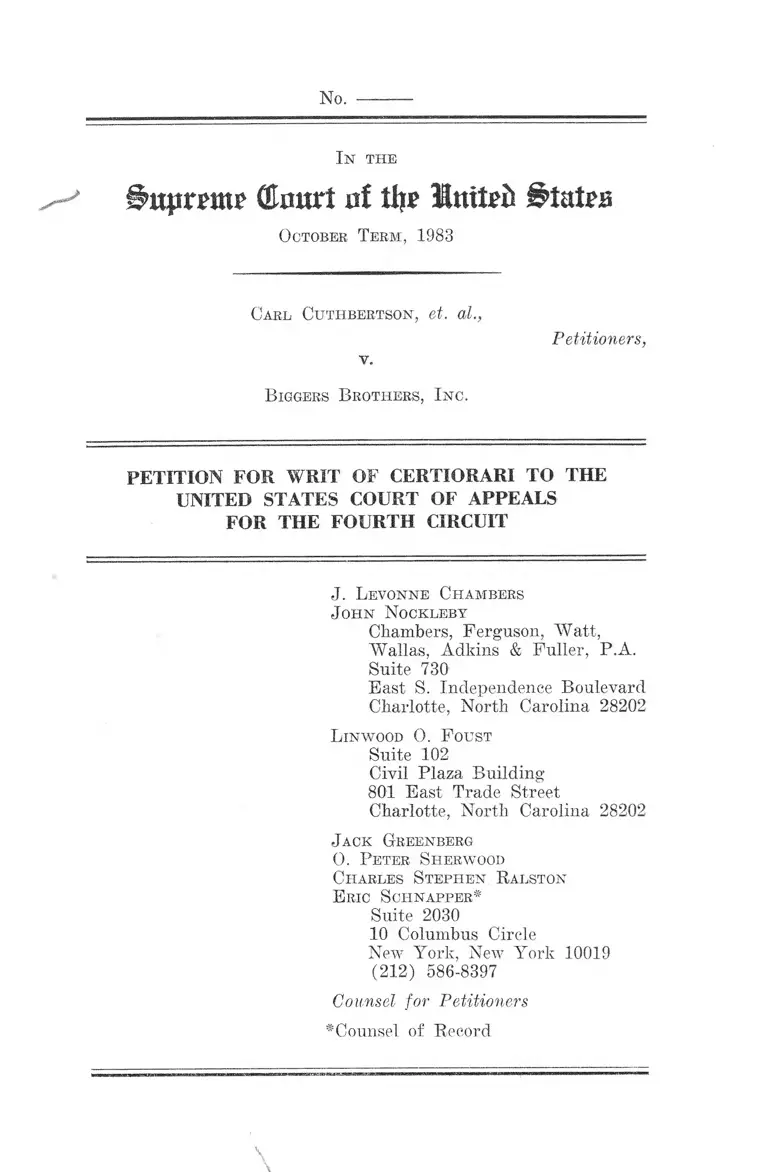

No.

In the

(tort nf ti|F United States

October Term, 1983

Carl Cuthbertson, et. al.,

v.

B iggbes Brothers, I nc.

Petitioners,

PETITION FOR W RIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

J. Levonne Chambers

John Nockleby

Chambers, Ferguson, Watt,

Wallas, Adkins & Fuller, P.A.

Suite 730

East S. Independence Boulevard

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

L in wood 0 . F oust

Suite 102

Civil Plaza Building

801 East Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

Jack Greenberg

O. Peter Sherwood

Charles Stephen. Ralston

Eric Schnapper*

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Counsel for Petitioners

^Counsel of Record

\

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Does Rule 52, F.R.C.P., authorize

the appellate courts to reconsider de novo

or give little weight to the decision of a

district court merely because the lower

court based its findings of fact on pro

posed findings submitted by counsel at the

direction of the court?

2. Did the court of appeals err in

concluding there was no substantial

evidence to support a finding of racial

discrimination where the record showed:

(i) that the defendant company had

never hired a black salesman

prior to 1976;

(ii) that company officials announced

in 1968 that "the time was not

right for blacks to be assigned to sales";

(iii) an owner of the company had

announced that he "wouldn't have

a black man sell a dog for him"; and

l

(iv) a company official testified in

1981 that it would not employ

black salesmen to work in certain

territories because of customer

hostility to blacks.

PARTIES

The parties to this proceeding in

this Court are Carl L. Cuthbertson, Brown

T. Worthy, Fred Johnson, Jr., Calvin

Gregory and Biggers Brothers, Inc. Eleven

* /other individuals” were named as plain

tiffs in this action, but they were denied

relief by the district court and did not

appeal from that decision.

V James H. Little, John Clay, James W.

Baldwin, Bobby Campbell, Jimmie Anderson,

Eddie Hicks, James Gill, Truemain Mainor,

Charles Neal, Hendrick Robinson, and

Willie Frazier, Jr.

11 -

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Questions Presented ..................... i

Parties ................................. ii

Table of Authorities .................... v

Opinions Below ................... 2

Jurisdiction ............................ 2

Rule Involved ........................... 3

Statement of the Case .......... 4

Reason for Granting the Writ ............ 7

Certiorari Should Be Granted To

Resolve A Conflict Among the Courts

of Appeals Regarding the Use of

Proposed Findings Prepared by

Counsel for a Party ................ 7

Conclusion ............... 24

- iii -

Page

APPENDIX

District Court Memorandum of Decision,January 30, 1981 . . . ............ ia

District Court Findings of Fact and

Conclusions of Law, September 16, 1981 .............. 6a

District Court Judgment, September16, 1981 ..................... 60a

Opinion of the Court of Appeals,

March 9, 1983 ..... 67a

Order of the Court of Appeals

Denying Rehearing and Rehearing

En Banc, June 13, 1983 ......... 1 1 7a

xv

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Arastar Corporation v. Domino's Pizza, Inc.,

615 F. 2d J.52 (5th Cir. 1980) ...... 15,21

Askew v. United States, 680 F.2d 1206(8th Cir. 1982) ................... 15,20

Bradley v. Maryland Casualty Co.,

382 F. 2d 415 (8th Cir. 1967) ...... 15

Chicopee Manufacturing Corp. v. Kendall

Co., 288 F.2d 719 (4th Cir. 1961) .... 18

Continuous Curve Contact Lenses v. Rynco

Scientific Corp., 680 F.2d 605 (9th

Cir. 1982) ....................... 17,21

EEOC v. Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond,

698 F.2d 633 (4th Cir. 1983) .... 19

Halkin v. Helms, 598 F.2d 1

(D.C. Cir. 1978) ..................... 12

Hill & Range Songs, Inc. v. Fred Rose

Music, Inc., 570 F.2d 554

(6th Cir. 1978) ...................... 13

Holsey v. Armour, 683 F.2d 864

(4th Cir. 1982) ................... 19

In Re Las Colinas, Inc.,

426 F.2d 1005 (1st Cir. 1970) ... 17,20,21

International Controls Corp. v. Vesco,

490 F. 2d 1334 (2d Cir. 1974) ......... 16

Kelson v. United States, 503 F.2d 1291

(10th Cir. 1974) ..................... 15

v

Pa^e

Mississippi Valley Barge Line Co. v.

Cooper Terminals, 217 P.2d 321(7th Cir. 1954) ....................... 14

O'Leary v. Liggett Drug Co.,

150 F.2d 656 (6th Cir. 1946)...... . 13

Ramey Construction Co. v. Apache Tribe,

616 F.2d 464 (10th Cir. 1980) ..... 17,20

Roberts v. Ross, 344 F.2d 747

(3d Cir. 1965) ........ ......... 15,16,21

Saco-Lowell Shops v. Reynolds,

141 F.2d 587 (4th Cir. 1944) .......... 17

Schilling v. Schwitzer-Cummins Co.,

142 F. 2d 82 (D.C.Cir. 1944) ....... . 12

ScheHer-Globe Corp. v. Milsco Mfg. Co.,

636 F.2d 177 (7th Cir. 1980) ___...... 14

Schlensky v. Dorsey, 574 F.2d 131

(3d Cir. 1978) ...................... 15

Schwerman Trucking Co. v. Gartland

Steamship Co., 496 F.2d 466 (8th Cir. 1974) ........... ........... 13

The Severance, 152 F.2d 916

(4th Cir. 1945) ........ ............ 18,19

United States v. Crescent Amusement Co.,

323 U.S. 173 (1945) ....... ......... 22,23

United States v. El Paso Natural Gas

Co., 376 U.S. 651 (1964) ......... . 23

vi

Page

White v. Carolina Paperboard Corp.,

564 F. 2d 1073 (4th Cir. 1977) ........ 18

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) ...................... 2

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ......................... 4

42 U.S.C. § 2000e ........................ 4

Rules:

Rule 52(a), Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure ......................... 3,9,11

Vll

UNITED STATES SUPREME COURT

October Termf 1983

No.

CARL CUTHBERTSON, et. al. ,

Petitioners,

v.

BIGGERS BROTHERS, INC.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners Carl Cuthbertson, et al.,

respectfully pray that a Writ of Certiorari

issue to review the judgment and opinion of

the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fourth Circuit entered in this proceeding

on March 9, 1983, petition for rehearing

denied June 13, 1983.

2

OPINIONS BELOW

The decision of the court of appeals

is reported at 702 F.2d 454, and is set

out at pp. 67a-116a of the Appendix.

The order denying rehearing, which is not

yet reported, is set out at p. 117a. The

district court's Memorandum Decision of

January 30, 1981, is not reported, and

is set out at pp. 1a-5a. The district

court's Findings of Fact and Conclu

sions of Law, which is not officially

reported, is set out at pp. 6 a-5 9 a .

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the Court of Appeals

was entered on March 9, 1983. A timely

Petition for Rehearing was filed, which

was denied on June 13, 1983. Jurisdiction

of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C.

§ 1254(1).

3

RULE INVOLVED

Rule 52(a), Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure, provides:

In all actions tried upon the facts

without a jury or with an advisory

jury, the court shall find the

facts specially and state separately

its conclusions of law thereon, and

judgment shall be entered pursuant

to Rule 58; and in granting or

refusing interlocutory injunctions the

court shall similarly set forth the findings of fact and conclusions of

law which constitute the grounds of

its action. Requests for findings are

not necessary for purposes of review.

Findings of fact shall not be set

aside unless clearly erroneous, and

due regard shall be given to the

opportunity of the trial court to

judge of the credibility of the

witnesses. The findings of a master,

to the extent that the court adopts

them, shall be considered as the

findings of the court. If an opinion

or memorandum of decision is filed, it

will be sufficient if the findings of

fact and conclusions of law appear

therein. Findings of fact and conclu

sions of law are unnecessary on decisions of motions under Rules 12 or

56 or any other motion except as

provided in Rule 41(b).

4

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

On July 21, 1977, petitioners com

menced this action in the United States

District Court for the Western District of

North Carolina. Their complaint alleged

that the defendant employer had engaged in

a pattern and practice of discrimination in

refusing to promote black employees to

sales positions, in violation of Title VII

of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. §§

2 0 0 0 e et se^., and 42 U.S.C. § 1981.

The district court conditionally

certified a class of all present and former

black employees. Following a non-jury

trial in January, 1981, the district court

issued on January 30, 1981, a Memorandum of

Decision. It held that the defendant had

engaged in a pattern and practice of

discrimination, and that it had for racial

reasons denied promotion to sales jobs to

5

petitioner Cuthbertson and three other

individuals. The trial judge rejected as

pretextual the standards allegedly used by

the company to deny promotions to peti

tioners, holding that the standards

were not reasonably related to the sales

jobs and that most white workers did not

themselves meet the purported requirements.

(1a-4a) The district judge directed coun

sel for plaintiffs to prepare a proposed

judgment, together with proposed findings

of fact and conclusions of law, and invited

the defendant to comment on those proposals

or offer proposals of its own (4a).

Following submission of these materials the

trial judge entered Findings of Fact and

Conclusions of Law in substantially the

form urged by plaintiff (6a-59a). The

district court decertified the class on the

ground that all of the identifiable victims

6

of discrimination were already named

parties to the litigation (42a-43a, 61a).

On March 9, 1983 the Fourth Circuit

reversed. It found there was no pattern or

practice of discrimination, and that

neither petitioner Cuthbertson nor two of

the other plaintiffs who had prevailed at

trial had been denied promotions on the

basis of race (67a-105a). The court of

appeals remanded the claims of petitioner

Worthy for a further hearing and for

additional factfinding ( 1 05a-114a ) . A

timely petition for rehearing and sugges

tion for rehearing £n banc was denied on

June 1 3, 1983, by a vote of 5-4. Judges

Winter, Phillips, Murnagham and Ervin voted

to rehear the case en banc (117a—118a).

7

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

Certiorari Should be Granted to

Resolve A Conflict Among the Courts of

Appeals Regarding the Dse of Proposed

Findings Prepared By Counsel for a Party

This petition presents one of the

extreme cases in which there is substantial

direct evidence of intentional discrimina

tion. The trial court found that in 1968

Black employees who sought promotion to

sales jobs were advised by the plant

manager that "the time was not right for

blacks to be assigned to sales" (2 0 a).

At trial in 1981 a Vice President of the

employer testified that it was still the

policy of the company not to place blacks

in sales jobs in certain parts of its

territory because it presumed its customers1/were too bigoted to deal with a black.

1/ Court of Appeals Appendix, pp. 281-83

(hereinafter "CA App.").

8

One witness testified that in 1971 Mr.

Biggers, one of the owners of the firm,

stated that he "wouldn't have a black

2/

man sell a dog for him". True to Biggers'

word, the company did not hire or promote a

black into sales until 1976, although the

total sales force was close to 100 and at

least 58 whites were hired or promoted into

3/such jobs between 1965 and 1976.

In view of this record, it is hardly

surprising that the district court found

that the company had engaged in a pattern

and practice of intentional racial dis

crimination in selecting sales employees.

What is extraordinary is that on appeal the

Fourth Circuit reversed that finding and

2/ CA App. 682.

2 / CA App. 371-73, 744-45

9

held that, with one possible exception, the

employer had never engaged in any such

discrimination. Four members of the court

of appeals voted for a rehearing en banc,

apparently recognizing that the panel

decision unjustifiably ignored the de

ference to the district court's decision

required by Rule 52, Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure.

The court of appeals panel felt free

to overturn the trial court's decision on

the merits, and to make light of the trial

judge's opinion, because the lower court

had asked counsel for plaintiff to prepare

proposed findings and, after considering

the comments of the defendant, had chosen

to adopt most of them. Many of the trial

judge's holdings resolved conflicts in the

evidence at trial; on appeal the Fourth

Circuit felt entirely free to reconsider de

10

novo the same conflicting evidence. For

example, a senior company official, under

examination by counsel for plaintiffs,

acknowledged that black delivery truck

drivers were qualified to work as salesmen,

but on cross examination by the company

retracted that admission. The trial judge

chose to believe the admission (8a-19a),

while the appellate judges, none of whom

had been present at the hearing or had

had occasion to observe the witnesses'

demeanor, chose to credit the retraction

(81a-83a). Plaintiffs and defendant

offered tables containing differing ac

counts of the qualifications of the whites

hired into sales. The trial judge accepted

plaintiffs' analysis, and thus concluded

that many whites never met the standards

which were used to reject Blacks (15a-19a);

the appellate judges, relying instead on

the defendant's evidence, reached the

opposite conclusion. (85a-92a) The trial

judge concluded that petitioners Cuthbert-

son, Gregory and Johnson were qualified to

work in sales (32a, 38a, 40a, 45a, 47a,

58a) the appellate judges held that they

were not (97, 101a, 103a, 105a, 108a). The

trial judge concluded that petitioner

Worthy had been the victim of discrimina

tion (34a, 46a, 51a); the courts of appeals

vacated and remanded that finding because

it felt "the record is incomplete for us to

make ... findings with respect to discrimi

nation...." (1 1 1 a) (emphasis added).

Although aware of the "clearly erro

neous" standard of Rule 52, Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure, the court of appeals

believed that it should accord the trial

court's findings "less weight and dignity"

(81a) — indeed, that it should virtually

decide the case de novo — solely because

the district court had adopted proposed

12

findings in essentially the form proposed

by counsel for plaintiffs. But the proce

dure utilized by the trial judge in this

case, and disapproved by the Fourth Cir

cuit, is expressly sanctioned in the

Sixth, Seventh and District of Columbia

Circuits. The court of appeals for

the District of Columbia most recently

rejected an attack on this practice in

Halkin v. Helms, 598 F.2d 1, 8 (D.C. Cir.

1978). That circuit court defended the

practice at length in Schilling v. Schwitz-

er-Cummins Co. , 142 F.2d 82 (D.C. Cir.

1944) :

Whatever may be the most commendable

method of preparing findings

whether by a judge alone, or with

the assistance of his ... law clerk

... or from a draft submitted by

counsel -- may well depend upon

the case, the judge, and facilities

available to him. If inadequate

findings result from improper reliance

upon drafts prepared by counsel — or

from any other case -- it is the

13

result and not the source that is

objectionable. 142 F.2d at 83 (foot

notes omitted)

In Hill & Range Songs, Inc, v. Fred Rose

Music, Inc. , 570 F.2d 554 (6th Cir. 1978),

the Sixth Circuit noted that it was "not

unusual" for a court "to adopt verbatim"

proposed findings of fact and conclusions

of law, and held that so long as those

findings and conclusions are supported

by the record "it makes no real difference

which counsel submitted them.” 580 F.2d

at 558. See also O'Leary v. Liggett Drug

Co. , 150 F. 2d 656, 667 ( 6th Cir. 1946 )

("findings of fact, prepared and submitted

by the successful attorneys, [which]

have been adopted by the trial court

... are entitled to the same respect as if

the judge, himself, had drafted them").

The Seventh Circuit upheld the practice in

Schwerman Trucking Co. v. Gartland Steam-

14

ship Co., 496 F . 2 d 466, 475 (8 th Cir.

1974), explaining:

By having the prevailing party submit

proposed findings of fact and conclu

sions of law, the judge followed

a practical and wise custom in which

the prevailing party has "an obliga

tion to a busy court to assist it

in performance of its duty" under

Rule 52(a).

See also Scheller-Globe Corp. v. Milsco

Mfg. Co., 636 F.2d 177, 178 (7th Cir. 1980)

("This circuit ... leaves the matter within

the trial court's discretion and recognizes

that the procedure can be of considerable

assistance to a trial court ...."); Missi

ssippi Valley Barge Line Co. v. Cooper

Terminal Co., 217 F.2d 321, 323 (7th Cir.

1954 ) ("It was perfectly proper to ask

counsel for the successful party to

perform the task of drafting the findings

" )• * • • /

But this use of findings prepared by

the prevailing party, a procedure described

15

by the Seventh Circuit as of "considerable

assistance" to the trial courts, has been

specifically disapproved, although in

4/ 5/varying degrees, by the Third, Fifth,

6/ 7/Eighth, and Tenth circuits. On the other

8/ 9/hand, the Third and Eighth circuits do

approve the use of findings drafted by

counsel if the trial court solicits and

considers such proposed findings from both

4/ Schlensky v. Dorsey, 574 F.2d 131,

148-49 (3d Cir. 1978); Roberts v. Ross, 344

F.2d 747, 751-53 (3d Cir. 1965).

5/ Amstar Corporation v. Domino's Pizza,

Inc. , 615 F. 2d J^2, 258 (5th Cir. 1980).

6/ Askew v. United States, 680 F.2d 1206,

1207-08 (8th Cir. 1982); Bradley v. Mary-

1 and Casualty Co. , 382 F.2d 415, 422-23

(8th Cir. 1967).

2/ Kelson v. United States, 503 F.2d 1291, 1294 (10th Cir. 1974).

2/ Schlensky v. Dorsey, 574 F.2d at 148-

49; Roberts v. Ross, 344 F.2d at 752-53.

9/ Bradley v. Maryland Casualty Co.,

F.2d at 423. 382

16

considers such proposed findings from both

sides prior to its decision on the merits.

In Roberts v. Ross, 344 F.2d 747, 752 (3d

Cir. 1965), the Third Circuit noted:

In most cases it will appear that

many of the findings proposed by one

or the other of the parties are

fully supported by the evidence,

are directed to material matters and

may be adopted verbatim and it may

even be that in some cases the find-

ings and conclusions proposed by a

party will be so carefully and objec

tively prepared that they may all

properly be adopted by the trial judge without change.

But the verbatim adoption of proposed

findings, sanctioned in appropriate cases

by these two circuits, is "roundly con-

1 0/demned" by the Second Circuit and ap

proved only in "highly technical" cases in

10/ International Controls Corp. v. Vesco,

490 F.2d 1334, 1341 n. 6 (2d Cir. 1974).

- 17 -

11/ 12/the First and Ninth Circuits. The

most recent Tenth Circuit opinion on this

subject states both that the verbatim

adoption of proposed findings "may be

acceptable under some circumstances" and

that it "is an abandonment of the duty

11/imposed on trial judges by Rule 52."

Consistent with this inter-circuit

conflict, the Fourth Circuit's position on

the use of proposed findings has undergone

a complete reversal in recent years. Saco-

Lowell Shops v. Reynolds, 141 F.2d 587, 589

11/ In Re Las Colinas, Inc., 426 F.2d 1005,

1009 (1st Cir. 1970) ("[T]he practice of

adopting proposed findings verbatim

should be limited to extraordinary cases

when the subject matter is of a highly

technical nature requiring expertise

which the court does not possess.”)

12/ Continuous Curve Contact Lenses v.

Rynco Scientific Corp. , 680 F.2d 605, 607

(9th Cir. 1982).

11 / __— •__A p a c heTribe, 616 F.2d 464, 466 (10th Cir. 1980).

18

(4th Cir. 1944), held that findings of fact

"are not weakened or discredited because

made by the trial judge in the form re

quested by counsel." In The Severance,

152 F.2d 916 (4th Cir. 1945), the trial

judge had requested the prevailing party to

draft proposed findings of fact and conclu

sions of law, and had adopted them "practi

cally in toto"; the court of appeals held

that ”[t]his practice is not to be con

demned." 152 F.2d at 918. Chicopee

_Kendall Co . ,

288 F .2d 719, 724-25 (4th Cir. 1961),

citing decisions in the Sixth and District

of Columbia circuits, noted there was

authority for "the adoption of such ...

proposed findings and conclusions as the

judge may find to be proper," and condemned

only the ex parte drafting of an opinion

by counsel for one of the parties. In

White v. Carolina Paperboard Corp., 564

19

F .2d 1073 (4th Cir. 1977), the court of

appeals, although criticizing the content

of particular findings adopted from the

proposals of counsel, expressed no per se

disapproval of the use of such findings,

and merely concluded that" [o]n remand, we

suggest the district court prepare its own

opinion." 564 F.2d at 1082-83. (Emphasis

added) In July, 1982, the Fourth Circuit

"cautioned against" the adoption of find

ings solicited by the trial judge from the

prevailing party. Holsey v. Armour, 683

F. 2d 864, 866 (4th Cir. 1982). In EEOC v.

Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, 698 F.2d

633, 640 (4th Cir. 1983) that "caution"

evolved into "disapproval". In the instant

case the Fourth Circuit announced that it

had "previously condemned" this practice,

inexplicably citing The Severance, which,

as we noted above, had held precisely

the opposite. (80a)

20

Those courts of appeals which do

disapprove the adoption of findings pre

pared by counsel are themselves in dis

agreement about how such findings should

be treated on appeal. No court regards

that practice as reversible error. In

11/at least some circumstances the First and

11/Tenth circuits will remand a case for

additional findings drafted by the trial

court itself. The Eighth circuit applies

the same "not clearly erroneous" rule

regardless whether the findings appealed

from were drafted by counsel or the trial

11/judge. Five circuits apply a special

11/ In re Las Colinas, Inc., 4 2 6 F.2d1005, 1010 (1st Cir. 1970).

1 5/ Ramey Construction Co._v_._Apache

Tribe, 616 F.2d 464, 467-69 (10th Cir.1980) .

16/ Askew v. United States, 680 F.2d 1206, 1208 (8th Cir. 1982).

21

standard of review when considering find

ings of fact adopted by the trial court

from proposals submitted by counsel. The

First Circuit conducts a "most searching

11/examination for error" in such cases.

In the Third Circuit findings drafted by

counsel are "looked at ... more narrowly

18/

and given less weight on review." The

Fifth Circuit will "take into account" the

19/origin of such findings, while the

Ninth Circuit subjects them to "special

20/

scrutiny."

As the very length and detail of

the Fourth Circuit opinion make clear,

17/ In re Las Colinas, Inc., 426 F.2d

1005, 1010 (1st Cir. 1970).

18/ Roberts v. Ross, 344 F.2d 747, 752 (3d

Cir. 1965).

19/ Amstar Corporation v. Domino's Pizza

Inc. , 615 F. 2d 252, 258 (5th Cir. 1980).

20/ Continuous Curve Contact Lenses, Inc.

v. Rynco Scientific Corporation, 680 F.2d

605, 607 (9th Cir. 1982) .

22

the widespread differences regarding

the use of findings prepared by counsel

raise equally serious issues regarding the

roles of the appellate courts. The inde

pendent factfinding apparent on the face of

the Fourth Circuit's opinion would not

have occurred in the three circuits which

approve use of such findings, or in the

Eighth Circuit which applies to them

the usual "not clearly erroneous" rule.

This division among the lower courts

stems in part from this Court's past

ambivalen** attitude towards findings

prepared by counsel. United States v.

Crescent Amusement Co., 323 U.S. 173

(1945), denounced the verbatim adoption of

proposed findings as "leav[ing] much to be

desired," and yet insisted "they are

nonetheless the findings of the District

Court." 323 U.S. at 185. United States v.

23

El Paso Natural _Gas_Co_1_, 376 U.S. 651

(1964) complained that such findings were

"not the product of the workings of the

district judge's mind," and nonetheless

held that they were "formally his" and thus

"not to be rejected out-of-hand." 376 U.S.

at 656. The confusion and division among

and within the courts of appeals cannot be

eliminated until this Court resolves the

conflicting implications of Crescent Amuse

ment and El Paso Natural Gas by determin

ing when if ever the adoption of findings

prepared by counsel is impermissible, and

by specifying what if anything the appel

late courts are to do when that occurs.

23

24

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons a writ of

certiorari should issue to review the

judgment and opinion of the Fourth Circuit.

Respectfully submitted,

J. LEVONNE CHAMBERS

JOHN NOCKLEBY

Chambers, Ferguson, Watt,

Wallas, Adkins & Fuller, P.A.

Suite 730

East S. Independence

Boulevard

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

LINWOOD 0. FOUST

Suite 102

Civil Plaza Building

801 East Trade Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

JACK GREENBERG

0. PETER SHERWOOD

CHARLES STEPHENS RALSTON

ERIC SCHNAPPER

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

(212) 586-8397

Counsel for Petitioners

*Counsel of Record

APPENDIX

IN THE DISTRICT COURT OF THE

UNITED STATES FOR THE

WESTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

Charlotte Division

C-C-77-196

JAMES H. LITTLE,* JOHN CLAY; BROWN T.

WORTHY; JAMES W. BALDWIN; BOBBY

CAMPBELL; JIMMIE ANDERSON; EDDIE HICKS

JAMES GILL; CARL L. CUTHBERTSON;

TRUEMAIN MAINOR; FRED JOHNSON, JR.;

CHARLES NEAL; HENDRICK ROBINSON; and

WILLIE FRAZIER, JR.,

Plaintiffs,

v.

BIGGERS BROTHERS, INC.,

Defendant.

MEMORANDUM OF DECISION

Pursuant to a non-jury trial on

January 15, 16 and 19, 1981, the court has

reached the following conclusions:

The defendant, through the relevant

periods, discriminated against black

employees on account of their race.

2a

Defendant followed a pattern and

practice of racially discriminatory job

assignments in respect of the "driver-

supervisors" who were listed as supervisors

but were de facto drivers without time to

perform their allegedly supervisory duties.

On racially discriminatory bases

defendant denied or delayed the promotion

of the plaintiffs Cuthbertson, Worthy,

Johnson and Gregory to sales jobs.

The discharge of the plaintiff Johnson

was not racially motivated.

The plaintiff Baldwin has not carried

the burden of proving that his discharge

was racially discriminatory.

The defendant throughout the periods

in question had somewhere between ninety

and a hundred different salesmen, of

whom most had a high school education or

less, and only approximately thirty-four

had any formal education beyond high

3a

school. No legitimate educational qualifi

cation for the job of salesman has been

demonstrated. Even the sales manager

had no formal education beyond high school.

The requirement of "sales experience"

has not been proved. The most useful sales

experience from the evidence appears to be

not actual on-the-road selling, but rather,

work in the warehouse, work in the order

department, and work as truck drivers. In

those three positions employees (a) learn

the stock, which is the most important area

of knowledge; (b) learn the customers; and

(c) learn how to process orders.

Selling for the defendant is not the

"Cadillac" of the sales world, as claimed,

but is, instead, a sales job which,

like all such jobs, requires more on-the-

job training than previous education or

applicable experience.

4a

Legitimate business reasons for

denying sales opportunities to the four

plaintiffs named were not shown. Racially

prejudice in their non-selection has been

shown.

Plaintiffs' counsel are directed to

prepare appropriate findings of fact,

conclusions of law and a judgment imple

menting the above basic decisions.

No class will be certified or con

tinued as to outside applicants because

none surfaced during the trial.

I am open to argument on the question

of decertifying the class as to internal

applicants for sales jobs. I am inclined

to de-certify the class. All the employees

who might file such claims are known, and a

notice to listed individuals, if there are

any, who should be notified will be better

than establishment of a class.

5a

Defendant will have thirty (30) days

following service of a copy of plaintiffs'

proposals in which to file exceptions

or alternative proposals. Such exceptions

should not take the form of simple indepen

dent statements of the defendant's posi

tion, but should be direct responses to

particular paragraphs and sentences of

plaintiffs' proposals, complete with the

text of alternatives, if any, requested by

defendant.

This 30 day of January, 1981.

James B. McMillan

United States District Judge

6a

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE

WESTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

Charlotte Division

CIVIL ACTION NO. C-C-66-196

JAMES H. LITTLE, et al. ,

Plaintiffs, v.

BIGGERS BROTHERS, INC.,

Defendant.

FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

This is another employment discrimi

nation proceeding. Fourteen present and

former black employees alleged that defen-1/dant, Biggers Brothers, Inc., denied

]_/ Defendant has gone through several

corporate changes or mergers since the

institution of this proceeding. It began

as a family owned operation and was pur

chased by Viands, Inc. It is now a wholly

owned subsidiary of Viands, Inc. Its

management, employees and operation,

7a

equal employment opportunities to black

employees and applicants for employment

based on race and color. Defendant's

practices allegedly violated Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§

2 0 0 0 e et seq. and 42 U.S.C. § 1981.

Jurisdiction of the Court was invoked

pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f) and 28

U.S.C. § 1343.

Defendant has consistently denied

plaintiffs' allegations and contended that

its employment practices, at least during

the time relevant to this proceeding, have

been free of racial discrimination.

]_/ continued

however, have remained basically the same.

No serious contention has been or could be

raised that the present employer is not

responsible for the employment practices of

defendant as discussed herein whether com

mitted by the former or present corporate

entity.

8a

By Order of February 12, 1980, the

Court conditionally certified the proceeding

as a class action, defining the class as

all black present and former employees

of the defendant Biggers Brothers,

Inc., and its predecessors, who have

worked for the company at any time

since August 6, 1975 (six months prior

to the charge [of employment discrimi

nation] filed by plaintiffs Worthy,

Baldwin, Johnson and Cuthbertson with

the Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission) in production and opera

tion, transportation, warehouse,

garage and maintenance, sales, super

visory, professional, technical,

clerical and other salaried and hourly

paid job positions, and who have been

denied equal employment opportunities

because of their race or color by the

defendant or its predecessor.

Leave was us "granted the defendant to move

for decertification after the conclusion of

discovery if discovery reveals substantial

grounds for contesting the existence of a

class."

Willie J. Tobias, Sr., a black em

ployee in warehousing, was allowed to

intervene on September 4, 1980. Tobias was

9a

within the class but moved to intervene,

alleging that he had been retaliated

against, demoted and discharged because of

his participation in this proceeding. He

had exhausted the administrative procedure

under Title VII and moved for a preliminary

injunction. His motion was deferred

pending trial on the merits.

The action was tried on January 15, 16

and 19, 1980. Based on the evidence

produced at trial, the briefs and arguments

of counsel for the parties, and the entire

record, the Court makes the following

findings of fact and conclusions of law.

FINDINGS OF FACT

1. Defendant operates a wholesale

and institutional food service distribution

center servicing restaurants, groceries,

institutions and other food retail estab

lishment. Its operation is divided into a

10a

general office, including sales, clerical

and professional job positions, warehouse

and transportation, garage and maintenance

and production where food products are

received, processed and stored for ship

ment. Superintendents and supervisors

are assigned to the various divisions.

2. Historically, black employees

have been assigned to warehousing, trans

portation and limited areas of production.

Although initially plaintiffs challenged

defendant's employment end promotion

practices in selecting employees for

clerical and professional positions and

supervisory positions, at trial plaintiffs

limited their contentions and proof to

defendant's practices in selecting employ

ees in sales and in its treatment of

Tobias and James Baldwin, a black employee

who was discharged by defendant because he

was physically unable to perform his

11a

truck driving duties. Plaintiffs contended

that he should have been assigned lighter

duties like white employees who had sus

tained on-the-job injuries. Additionally,

plaintiffs contended that the black super

visors were treated differently and ac

corded less job status and opportunities

than white supervisors, solely because

of race.

3. Plaintiffs' earliest charge of

discrimination was filed with the Equal

Employment Opportunity Commission on

February 6, 1976. The parties have agreed

that the earliest period for which plain

tiffs may seek relief under Title VI is 180

days prior to the charge or August 10,

2/1 975. Between that date and the date

2/ Although the defendant did not chal

lenge the beginning date of liability under

Title VII as set forth in the class defini

tion, the correct date is August 10, 1975.

Liability under Title VII is, therefore,

12a

of trial, defendant employed between 376

and 532 employees, 30 to 40 percent of

whom were black. Black employees, however,

were principally assigned to operative and

semi-skilled job positions. Defendant's

EEO-1 reports for 1975-1977 show the

following job family distribution by

race:

Total

̂975 Employees Black

1/49 9

Official and Managers 3 0Professional 15 1Technicians 62 0Sales workers 46 8Office and clerical 16 2Craftsmen (skilled) 167 124Operatives 23 20Laborers 3 1Service workers

2/ continued

limited to this date. See Note 24 infra as

to the statutory period of liability under 42 U.S.C. § 1981.

3/ Black employees listed as official and

managers are assigned principally as

supervisors in the predominantly black

13a

1976 Total

Employees Black

Official and Managers 38 13Professional 3 0Technicians 12 0Sales workers 90 0Office and clerical 96 12Craftsmen (skilled) 20 7Operatives 202 139Laborers 17 9Service workers 4 1

1977 Total

Employees Black

Official and Managers 45 10

Professional 4 0

Technicians 10 1

Sales workers 69 1

Office and clerical 45 27

Craftsmen (skilled) 16 4

Operatives 180 151

Laborers 7 7

Service workers 5 1

3/ continued

transportation division. For example, the

9 blacks listed in this category in 1975

were all in transportation; 7 of the 10

blacks in this classification in 1977 were

in transportation; the others were in the

warehouse and production, another division

where black employees were principally

assigned.

14a

4. Defendant's truck drivers are

paid on an hourly and varied salary

basis.-/ Other hourly paid employees

perform manual labor (receiving, storing

and shipping food products) and work in

maintenance. Salaried employees consist of

supervisors, managers and office employees.

Salesmen are paid a straight salary during

training and are then placed on commission.

Except for managers, salesmen earn on an

average substantially more than other

employees. Jobs in sales, therefore, are

the most attractive jobs.

5. Sales employees have generally

been promoted from within the workforce or

hired from new applications. Defendant

suggested that it preferred employees in

4 / Varied salary consisted of a base

salary plus a percentage increase based on

mileage and time travelled by truck drivers.

15a

sales who had college training, previous

food sales or restaurant experience, who

were neat in appearance and who were able

to communicate. Defendant's practices,

however, and other evidence before the

Court, failed to indicate a consistent

pattern except that the candidate be

5/white.

6. Charles L. Black serves as Vice

President in charge of sales. He has a

high school education with no other formal

education, except a course at Queen's

5/ Here, as in several other instances

which follow, the Court has had to resolve

conflicting evidence of the parties.

Despite the testimony of defendant's

witnesses regarding the criteria defendant

has used in selecting salesmen, the docu

mentary evidence — the personnel files and

other records reflecting the qualifications

of persons selected as salesmen, as well as

the admission of defendant's witnesses

simply refute defendant's assertions that

the criteria indicated have been consis

tently applied.

16a

College in Charlotte in management. He has

been in charge of sales since 1970. He

started with the company in 1952 in the

warehouse and went into sales in 1958. He

worked in the ordering department in sales

for 2 years and then became a sales rep

resentative. He has been sales manager

since 1967.

7. Lex Plyer, Melvin Richardson,

Oren Biggers, Bill Gardner and Rhudy

Johnson serve as supervisors in sales.

Neither holds a college degree. Only

Plyer, Biggers and Johnson have some

college training — Plyer 3 to 4 years,

Biggers 1 to 2 years and Johnson 1 year.

All of the supervisors had limited or no

previous sales experience in foods.

8. Plaintiffs' trial exhibit 22

lists defendant's salesmen with their

education and prior experience during the

relevant time period. The education and

1 7a

prior experience of salesmen demonstrate

that neither college training nor prior

sales experience has been a determining

6/factor in their selection.

9. Defendant also contends that

after selection as a salesman, training in

ordering various food products is an

essential factor. Such training, defendant

contends, exposes one to the defendant's

6/ During the relevant time period,

approximately ninety to one hundred differ

ent persons worked for defendant as sales

men. Although most of them had high school

educations, only thirty-four had any

formal education beyond high school. No

legitimate educational qualification for

the job of salesman has been demonstrated.

Even the sales manager, as indicated above,

had no formal education beyond high school.

Moreover, the need for sales experi

ence was not demonstrated. As found

herein, the most useful sales experience

was work in the warehouse, work in the

order department, and work as truck driv

ers. In these three positions, employees

(a) learn the stock, which is the most

important area of knowledge? (b) learn the

customers; and (c) learn how to process

orders.

18a

products and sales procedures. Defendant

admits, however, that the same or more

significant training is obtained by truck

drivers who deliver various products of

defendant and who frequently handle sales1/of various products.

10. Defendant’s practices in select

ing salesmen reveal the following:

(a) Historically, at least prior to

the filing of plaintiffs' charges,

no black employee or applicant in

defendant's history had been

selected as a salesman;

(b) White employees and applicants

have been selected as salesmen

with no prior sales experience or

education beyond high school; 8/

2/ See trial testimony of Charles Larry

Black Vice President in charge of sales.

8/ Plaintiffs' exhibit 22 shows the

educational background and prior work

experience of all salesmen in defendant's

work force during the relevant time period.

The education and prior work experience

were taken from the personnel files of the

employees. Although the personnel files

may not reflect all of the educational

training and work experience of the employ-

19a

(c) Training in ordering food pro

ducts with defendant may help in

preparing for a sales position;

such training, however, is

neither essential nor necessary

for one to perform successfully

as a salesman; 9/

(d) Truck drivers with the defendant

acquire the necessary experience

to be successful as a salesman.

They learn defendant's products,

must deal with defendant's

customers and generally acquire

equal or more relevant job

experience for sales positions

than employees who work in

restaurants or other food estab

lishments, for example, clerk in

grocery, butcher or cashier.

11. Beginning in 1968, black employ-

8/ continued

ees, the records demonstrate, and the Court

finds, based on the testimony and decorum

of defendant's witness, that they are

substantially reliable. Defendant does not

question, for example, that most of its

salesmen had no more than a high school

education and that most had no prior food

sales experience. Nor does defendant

question that the preferable and most

important experiences are those set forth

in footnote 6, supra.

9/ See notes 6-8, supra.

20a

ees of defendant requested transfers or

promotions to scales. They complained that

they were being limited to jobs in produc

tion, in the warehouse and as truck

drivers. They also alleged that black

supervisors in transportation were treated

differently and less favorably than white

supervisors in other departments.

12. The then plant manager arranged a

meeting with the black employees to discuss

the issue. Black employees were advised

that the time was not right for blacks to

be assinged to sales. Although sales

positions were filled during this period,

no black employee or applicant was se

lected. Plaintiff Brown Worthy was prom

ised a sales position but was not selected.

13. Plaintiff Carl Cuthbertson talked

with the plant manager about a sales

position in 1972. He continued to request

assignment to sales until he filed a charge

21a

of discrimination with the Equal Employment

Opportunity Commission (hereinafter EEOC or

Commission) on March 10, 1976. Between

1972 and the date of Cuthbertson's charge,

more than 15 white employees, for example,

Daryl L. Bandy in 1973, Edward Earl Bass in

1976, Frederick A. Caudle in 1973, Terry

Lee Centry in 1976, Walter W. Hanna, Jr.

In 1976, John Harris in 1975, Donald Holmes

in 1975, Rhudy Johnson in 1973, Carl Allen

Jones, Jr., in 1976, John Mitchell, Jr. in

1973, Winston F. Parker in 1976, Beaumond

D. Patterson in 1975, Charles L. Thomas in

1973, Joseph B. Whitaker in 1975, Bruce

Fant in 1975 and Ben Williams in 1975, were

hired in sales. No black, however,

was hired in sales until Cuthbertson' s

promotion in November, 1976.

14. Following Cuthbertson's charge,

defendant's personnel manager began to

contact some black employees about their

22a

interest in sales. A notice of vacancies in

1 0/sales was posted after the charge.

Twelve employees applied, including 4 black

employees. The notice advised employees

that the initial salary for the position

would be between $150.00 and $200.00 weekly

and that the employee selected would

be required to relocate.

15. The posted salary discouraged

black truck drivers who were already

earning in excess of $200.00 weekly.

Defendant did not advise the applicants

that they could earn substantially more

11/following completion of sales training.

11/ This was the first and apparently the

only instance in which any vacancy notice has been posted.

11/. As a general practice, sales trainees during the relevant time period were paid

between $150.00 and $200.00 weekly which

was less than the weekly average salaries

of truck drivers. Upon completion of the

trainee program, however, salesmen could

and did earn substantially more than truck drivers.

23a

16. The relocation requirement also

discouraged some applicants. Defendant did

not advise the applicants of the sales

vacancies in Charlotte which required no

relocation. For example, following

Cuthbertson's charge, 13 salesmen were

employed for the Charlotte office between

July and November, 1976.

17. Plaintiff Cuthbertson was the

first black so assigned. He completed his

training and was assigned as a sales

representative in May, 1977. Two other

blacks (Harold Kelly in November 1977 and

12/Wayne Banks in May, 1979) and 37 white

employees (see defendant's exhibits

43 and 44) were subsequently assigned to

sales.

12/ A Spanish surname (Roberta Alcala) was also assigned to sales during 1976.

24a-

18. Plaintiffs presented statistical

analyses which tended to show that blacks

constituted between 8.73 and 29.46 percent

of the relevant job market from which

defendant selected salesmen. Under plain

tiffs' analyses, defendant's underutiliza

tion of blacks in sales positions during

the period covered by plaintiffs' data

(1965 through 1978) ranged from 1.96 to

3.16 standard deviations, using the bino

mial analysis. Defendant's statistical

analyses did not refute plaintiffs' conclu

sions with respect to the underutilization

of blacks in sales positions. Defendant

used the 1970 Census as the availability of

blacks for sales jobs -- 4.1 percent

for the Charlotte Standard Metropolitan

Statistical Area. Defendant, therefore,

concluded that the standard deviations,

in sales, for the period 1 975 to 1 980,

ranged from 1.07 to 1.71.

25a

Defendant's availability analysis

ignored the promotion and hiring practices

of the company and the increased opportuni

ties blacks have enjoyed in sales positions

generally since the 1970 Census. For

11/example, 5 of the 15 salesmen hired

promoted in Charlotte be tween 1 976 *

1980 were promoted from within. The

incumbent employees, therefore, constitute

a significant part of the relevant source

from which salesmen have been selected.

Additionally, salesmen have been selected

1_4/

from clerical and operative job families

±5/

as well as from laborers. Defendant

however, limited its consideration to

13/ Fred Parker, Dan Harris, Jake Hanna,

Carl Jones and Tom Miller. See, e. g. ,

defendant's exhibit 43.

14/ As defined by the Census and EEOC.

15/ See plaintiffs' exhibits 22 and 23.

26a

employees who had worked or who were

presently working as salesmen.

North Carolina Labor Department and

supplemental United States Census data

reflect a significant increase of black

employees in sales positions since the 1970

Census. According to the 1979 Statistical

Abstract of the United States, Table #687,

black salesmen nationally increased from

3.08 percent in 1970 to 5 percent in

1 6 /1978. Black clerical and operative

employees increased from 7.36 and 12.65

percent respectively to 19.5 and 15.0

percent.

Thus, it is obvious that minority

availability for sales positions between

1975 and 1980 was higher than the 4.1

16/ The minority availability for the

Charlotte SMSA should be higher since

minority availability in 1970 was higher

than the nationwide average — 4.1 percent

as compared with 3.08 percent nationwide.

27a

percent used by defendant. The Court finds

that minority availability during the

<*

period is more accurately shown by plain

tiffs' Exhibit 23, Tables 3 and 4. Table 3

analyzes promotions from within defendant's

workforce in order to determine minority

availability. It establishes that 38.97

percent of the internal promotions into

sales should have been black. Externally,

11/8.73 percent of the new hires in sales

should have been black. Prior to Cuthbert-

son's charge in March 1976 and subsequent

promotion in November 1976, no black was

hired externally or promoted internally

into sales. While 2 blacks were hired and

1 promoted into sales following Cuthbert-

son's charge, defendant's utilization of

black employees in sales prior to that time

could not have happended by chance in

17/ See plaintiffs' Exhibit 23, Table 4.

- 28a

5 in 100 times. The Court believes that

defendant began hiring blacks into sales in

1976 after the EEOC charges and only as a

result of plaintiffs' charges.

19. Plaintiffs, however have not

relied exclusively on statistical dispari

ties; rather, 5 plaintiffs (Carl Lee

Cuthbertson, Brown Worthy, Fred Johnson,

Calvin Gregory and James Baldwin) testi

fied and presented evidence of the dis

parate treatment that they suffered.

Carl Lee Cuthbertson.

20. Cuthbertson was first employed by

defendant as a permanent employee on

December 3, 1970. He was assigned to the

1 8/

18/ For example, plaintiffs' Exhibit 23,

Table 13, shows 57 employees hired and

promoted into sales between 1 965 and

1978. Forty-eight of the 57 employees were

new hires and 9 were promoted. Using 8.73

availability for new hires and 38.97

availability for promotions, Table 13 shows

that this occurrence would not be expected by chance in 1 in 1000 times.

29a

warehouse. At that time, no black employee

worked in sales. Beginning in 1972, Cuth-

bertson, then a high school graduate,

requested promotion to sales. He was ad

vised by management to take some addi

tional courses, although white employ- 19/

ees were not required to take train

ing. Cuthberston enrolled in courses

at Central Piedmont Community College. He

again sought promotion into sales in

1 973, 1 974 and 1 975, but was rejected.

Cuthbertson filed an EEOC charge in

March 1976. He was not placed in a sales

position, however, until November 1976.

Defendant's Exhibits 43 and 44 show the

19/ For example, Daryl L. Bandy promoted

into sales in 1973 with a high school

diploma; Frederick A. Caudle promoted into

sales in 1973 with a GED; Jerry L. Church

ill was hired into sales in 1971 with a

high school diploma. In fact, over two-

thirds of defendant's salesmen had no

formal educational training beyond high school.

30a

following promotions to or hires in sales

20/

during 1976, prior to Cuthbertson's

selection:

Date of

Assignment

Race in Sales Education

Fred Parker W January 1976 H.S. -

2+ years

college

Ed Bass W February

1976 H.S.

Terry Cengry w March 1976 H.S. - MBA

(May 1976)

Vance Abbott w Apirl 1976 H.S. - A.S.

Degree

David Holly w June 1976 H.S.

Dan Harris w July 1976 H.S. - 3

years of

college

20/ Two employees were hired in sales in

1975 {James Lybrand and Winston Parker)

with no more qualifications than Cuthbert-

son. Four (Ben Williams, Jr., Charles

Thomas, John D. Harris and Jerry Conder)

were hired in 1975. At least 1 (Harris)

had even less qualifications than Cuth- bertson.

- 31a

Jake Hanna W July 1976 H.S. - 4

yrs. col

lege degree

Carl Jones W July 1976 H.S. - 1+

year college

Tim Miller W July 1976 H.S. - B.S.

They had the

Degree

11/following work experience:

Parker except for 6 months as order

selector in A & P Warehouse,

none in food sales

Bass 22 years

Gentry 4 months

Abbott none; 1 year route salesman

for Buttercup ice cream

Holly 7 years

Harris none; worked as cashier clerk

in drug store during college

Hanna none

Jones 2 1/2 years

Miller none; stock clerk in A & P

Food Store for 5 months

21 Prior work experience has been taken

collectively from defendant's Exhibits 43

and 44 and Plaintiffs' Exhibit 22.

32a

Cuthbertson worked in the warehouse

for 2 years and as a truck driver from 1972

until his promotion to sales in 1976,

experience which defendant admitted were

comparable if not more relevant to sales

than the prior work experience of some of

the white employees selected for sales

between 1974 and 1976. Cuthbertson also

completed 1 1/2 years of study beyond high

school before his promotion to sales.

21. Defendant offered no credible

evidence to explain its non-selection of

Cuthbertson in sales until after his charge

of discrimination. The Court finds that

Cuthbertson was not offered a sales posi

tion until November 1976, solely because of

his race.

Brown T . Worthy

22. Worthy was employed by defendant

as a laborer in the warehouse in 1963. He

promoted to truck driver in 1963 and to

33a

supervisor in 1967. Beginning in 1968,

Worthy and other blacks requested promotion

to sales. Although Worthy was promised a

sales position in 1970 and made preparation

to move to assume the position, he was not

assigned to sales. He continued his

efforts to promote to sales until after

his EEOC charge on February 6, 1976. He

22/

was offered but rejected a sales position

in June, 1976. At that time, Worthy had

given up hope. He and his family had

resolved that he would continue in his

supervisory position, rather than risking

the possibility of being reassigned to

22/ As supervisor during this period, Worthy and other black supervisors in

transportation principally filled in as

relief drivers when other drivers were away

from work. Because of their supervisory

classification, they were not able to earn

varied or overtime salaries as regular

truck drivers, despite the number of

hours they spent driving trucks. See Paragraph 24, infra.

34a

another location.

23. Worthy had 2 years of college

training and had worked in the warehouse

and in transportation since his employment.

He was qualified for the sales position by

24/his education and training. He should

have been promoted to sales in 1970, in

23/

23/ Salesmen were subject to assignment in

different districts.

24/ Defendant offered at trial some

writing samples of Worthy and testimony

that he was unqualified for sales. The

documentary and other evidence shows his

contention to be unreliable. As a truck

driver and supervisor, Worthy was required

to write and to prepare sales and delivery

reports and to report on the performance

of employees under his supervision. He was

knowledgeable of defendant's products, a

factor defendant contended was important;

he was able to calculate sales and was

equally or more qualified than several of

the salesmen selected by defendant between

1974 and 1976; for example, Lybrand in

1974, Harris and Williams in 1975 and Bass

in February 1976. In fact, defendant

promised a sales position to Worthy in 1970

and 1976, and again in 1977 with no conten

tion that he was unqualified. The Court

resolves this dispute in testimony in

Worthy's favor.

35a

1974 and 1975 or prior to his charge in

1976.

24. Worthy and other black super

visors complained about their limited

status as compared with white supervisors.

Black supervisors in transportation were

unable to hire or discharge employees.

They assigned responsibilities and selected

employees for particular job assignments

25/only as directed by their supervisors.

They supervised at times an all-black work

force and they spent a major portion of

their day not in supervising but in relief

driving, filling vacancies of regular

25/ Defendant contended at trial that

black supervisors had more responsibility

and referred to Worthy's discharge of

plaintiff Fred Johnson as an example.

Johnson, however, was discharged in 1977

following defendant's change in policies

regarding the black supervisors in trans

portation. Additionally, in discharging

Johnson, Worthy simply carried out the

express orders of his superintendent.

36a

drivers. Following Worthy’s charge,

defendant made changes in the job duties

and authority of transportation super

visors, making them comparable to those of

26/other supervisors.

Fred Johnson

25. Johnson was employed by defendant

in the warehouse on July 1 6, 1 969. He

subsequently promoted to truck driver and,

in 1975, to supervisor in transportation.

Johnson requested promotion to sales in

1974 and continued his efforts until his

discharge on July 22, 1977.

26/ Worthy and other black supervisors

also questioned defendant’s assignment of

both white, to

in trans-

exercised

employees

were not

Defendant

explained, however, that Ramsey and Robin

son were only temporarily assigned to these

jobs in order to assist defendant in

conducting a survey of its routes and

drivers. No discrimination is found in the

assignments of Ramsey and Robinson.

Dave Ramsey and R. Robinson,

assist in supervising employees

portation. Ramsey and Robinson

more control over transportation

than the black supervisors and

required to do relief work.

37a

26. Johnson filed a charge of dis

crimination with EEOC on February 6, 1976.

He complained about his inability to

promote to sales and defendant’s different

treatment of black and white supersivors.

27. Following his charge, Johnson

began to experience problems with his job,

receiving complaints about his relationship

with customers and job performance until

27/his discharge.

28. Johnson is a high school graduate

with some additional studies at Carver

College and Central Piedmont Community

College. He was knowledgeable about

defendant's products and customers from

his warehouse and transportation experi-

27/ Johnson presented limited proof

regarding his discharge at trial. His

evidence does not demonstrate that he was

treated differently with respect to his

discharge than other employees.

38a

ence. He was qualified for a sales posi-

28/

tion.

29. As indicated, defendant had

vacancies in sales in 1974, 1975, 1976 and

1977. Defendant offered no explanation of

its failure to promote Johnson to sales in

1974, 1975 and 1976. In 1977, Johnson

refused to sign the notice of vacancies in

sales. Defendant contends that Johnson was

not interested at that time because of the

salary paid during training. Johnson and

other black employees, however, were not

advised of the salary increases upon

completion of training. He was clearly

interested in and qualified for the posi-

28/ Defendant contended that Johnson was

unqualified for sales because of two

experiences he had with customers. These

incidents, however, came only after John

son's charge and, as the credible evidence

indicates, involved only 2 of the number of

customers serviced by Johnson. They

had no bearing on Johnson's rejection

between 1974 and 1976.

39a

tion in 1974, 1975 and 1976. His interest

and qualification continued until his

discharge in 1977.

Calvin Gregory

30. Gregory was employed by defendant

as a truck driver in 1973. He is a high

school graduate with additional college

training. He began efforts in 1976 to

promote to sales. He applied again

in 1977 with the posting. Gregory filed a

charge with EEOC on May 2, 1977. He was

advised that he would have to take a

reduction in pay and be transferred. He

was not advised about the vacancies

in Charlotte or the salaries in sales upon

completion of training. Based on defen

dant’s representation, Gregory withdrew his

1977 request. He would not have done so,

however, if he had known about salaries in

sales following training, even if he had

been required to relocate.

40a

31. Gregory was discharged on July

20, 1989. He does not challenge his

dismissal on this proceeding. He was

interested in and qualified for a sales

position, however, between 1976 and the

date of his discharge.

James Baldwin

32. Baldwin was employed by defendant

in transportation in 1964. He was injured

in 1975, suffered permanent injuries

which prevented him from performing his

regular job. Baldwin requested that he be

assigned "light duties." He complained to

EEOC following the defendant's refusal to

so assign him.

29/33. Baldwin contended that white

employees with similar injuries had been

29/ Baldwin also raised a claim initially

regarding his inability to promote to

sales. He abandoned this position at trial

and introduced no evidence in support of

this contention.

given limited assignments which enabled

them to continue their employment.

The 4 employees (Bryant Williams, R.

Robinson, David Ramsey and J. Hargett)

referred to by Baldwin, however, were not

assigned light duties; rather, they con

tinued with basically the same duties they

performed before their illness or injuries.

Additionally, Baldwin has a 7th grade

education and is limited in the type of

clerical or other light duties that he

can perform.

Willie Tobias

34. Tobias complained in his motion

to intervene that he had been discrimina-

torily demoted from his dock supervisory

position in 1977 and discharged on May 15,

1980. Tobias, however, introduced no

credible evidence to support his claim.

Other Named Plaintiffs

35. The evidence does not show that

42a

other named plaintiffs have been treated

differently or denied job positions because

of their race or color.

The Class Claims

36. While plaintiffs' statistical

evidence establishes that black employees

were excluded from sales positions, at

least through November 1976, and that this

exclusion was statistically significant,

plaintiffs did not produce at trial an

unsuccessful, outside black applicant for a

sales position. All incumbent black

applicants or interested parties are well

known and could be joined in this proceed

ing had they desired to pursue claims that

they were denied sales positions because of

their race.

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

1. The Court has jurisdiction of the

parties and of the subject matter. Plain

43a

tiffs have invoked the Court's jurisdiction

under Title VII, 42 U.S.C §§ 20GQe et seq.

and under 42 U.S.C. § 1981. Plaintiffs

filed timely charges with EEOC and timely

instituted this action following receipt of

right-to-sue letters from the Commission.

2. Based on the evidence presented

at trial, the Court concludes that the

class action, previously certified, should

be decertified. No evidence was presented

by plaintiffs of unsuccessful, outside

black applicants for sales or other job

positions. Although the evidence does

demonstrate that incumbent black employees

were discriminatorily denied jobs in sales,

all of these employees are known; they are

limited in number and could have been

easily joined in this proceedings. See

Kelley v. Norfolk & Western Railroad Co. ,

485 F . 2 d 3 4 (4th Cir. 1978). Since

former class members, as the class was

44a

previously defined, may have relied on this

proceeding to protect their interest, an

appropriate notice should be directed

to them advising of the decertification of

the class. Shelton v. 1̂ n ,

582 F .2d 1298 (4th Cir. 1978) and on

remand, 81 F.R.D. 637 (W.D.N.C. 1979).

3. Plaintiffs Cuthbertson, Worthy,

Johnson and Gregory alleged that black

employees and applicants for employment

were historically excluded from job posi

tions in sales because of their race.

They have established that prior to their

30/charges of discrimination, no black had

30/ The earliest charge was filed on

February 6, 1976. The earliest period of

liability therefore is 6 months prior to

the charge or August 6, 1975 for purposes

of Title VII. See Wetzel v. Liberty Mutual

Insurance Co.. , 508 F.2d 239, 246 (3d

Cir. 1975). Since this action was filed on

July 21 , 1 977, the period of liability

under 42 U.S.C. § 1981 begins July 21,

1974, 3 years prior to the institution of

this proceeding. N.C. Gen. Stat. § 1-52.

45a

been employed in sales; that they and other

blacks sought sales positions as early as

1968 and continued those efforts thereafter

without success until Cuthbertson was

promoted in 1976; that they were qualified

for the positions; that vacancies existed;

that defendant passed over them and se

lected white employees with no more qual

ifications than the plaintiffs and in

several instances, with less qualifica

tions. Under McDonnell-Douglas Corp. v.

Greene, 411 U.S. 792 (1973), plaintiffs'

evidence establishes a prima facie case of

disparate treatment and liability under

Title VII and 42 U.S.C. § 1981. See also,

International Brotherhood of Teamsters

v. United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977);

Texas Department of Community Affairs v.

B u jr d; Jjn ê , ___U . S . ____ , 67 L . Ed . 2d 207

(1981). While disparate treatment requires

proof of intent, Teamsters, 431 U.S.

46a

at 335 n. 1 5 , "failure to show conscious

intent to discriminate does not preclude a

finding of discriminatory intent." Russell

v. American Tobacco Co. , ___ F. Supp. ___

(M.D.N.C. Civ. No. C-2-G-68, July 10,

1981); citing Village of Arlington Heights

v. Metropolitan Housing Dev. Corp., 429

U.S. 252, 266 (1977).

4. Worthy requested a sales position

in 1968. He was promised a sales job in

1970. He made preparation to assume the

position but was never selected. He

continued his efforts thereafter through

the filing of his charge in February 1976.

He was qualified for sales, vacancies

existed but defendant refused to select

him. He was offered a sales job in June,

1 976 , but at that time was no longer

interested. Worthy's proof establishes a

prima facie case of liability until the

change in his position in June, 1976.

47a

5. Cuthbertson requested a sales

position in 1973. He was qualified at that

time but rejected because of his race.

He continued his efforts to promote to

sales, filed a charge in March, 1976, and

was finally selected in November, 1976.

Cuthbertson established a £rima facie

case of liability at least until the

11/date of his promotion to sales in 1976.

6. Gregory applied for a sales job

in 1976. Although qualified and vacancies

existed, Gregory was denied promotion to

sales. He was discharged on July 20, 1980.

31/ Cuthbertson contends that had he been

selected earlier, he would have completed

his training before March 1977, and would

have been earning substantially more than

he earned during 1976 and 1977. The relief

issue was separated from the liability

issue and was not developed at trial. The

Court, therefore, expresses no opinion on

this contention and will refer this issue

together with other relief issues to a

Master.

48a

Gregory's proof established a prima facie

case of liability.

7. Johnson sought a sales job in

1974 and continued his efforts until his

discharge on July 22, 1977. Johnson was

qualified and vacancies existed. His proof

establishes a prima facie case of liability

until his discharge on July 2 2 , 1977.

8. Once a prima facie case of

liability is established, defendant must

offer some evidence that "the plaintiff was

rejected, or someone else was preferred,

for a legitimate, nondiscriminatory

reason." Burdine, supra, 67 L.Ed.2d at

216. Although defendant does not assume

the burden of proof and need not persuade

the Court, its evidence must "raise a

genuine issue of fact as to whether it

discriminated against the plaintiff. To

accomplish this, the defendant must clearly

set forth, through the introduction of

49a

admissible evidence, the reasons for the

plaintiff's rejection. The explanation

provided must be legally sufficient to

justify a judgment for the defendant."

I b Ail. If the defendant is silent or

if its explanation is simply pretextual, it

runs the risk of an adverse determination.

Ibid . ; Furnco Construction Co. v. Waters,

438 U.S 567 (1978); Board of Trustees of

Keene State College v. Sweeney, 439 U.S.

24 (1978); EEOC v. American National Bank,

___ F. 2d ___ (4th Cir., Nos. 79-1533 and

79-1725, June 26, 1981).

9. Defendant offered no acceptable

explanation for its failure to employ a

black in sales prior to plaintiff's charges

32/

in 1976. The alleged criteria which de-

32/ As set out in the Findings, Paragraph

18, supra, both parties presented statisti

cal evidence in support of their conten

tions. And while the Court is persuaded

50a

fendant claims it utilized, see Findings of

Fact, Paragraphs 5, 9 and 10, to select

salesmen do not withstand scrutiny. The

standards simply were not followed when

whites were hired or promoted or in Bur-

dine, supra, terms were pretextual. The

Court concludes that blacks were not hired

in sales solely because of their race. It

offered some explanation for its failure to

promote Worthy, Cuthbertson, Gregory and

Johnson. Its suggested reasons, however,

do not withstand analysis and are patently

pretextual.

10. Defendant suggested that Worthy

could not write and thought he knew more

32/ continued

that defendant's underutilization of blacks

in sales prior to November 1976, is sta

tistically significant, this fact is not

essential for the Court's determination.

It simply supports the results reached by

the Court.

51a

than he did. Defendant selected Worthy