Wright v. United States Steel Corporation Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellees

Public Court Documents

April 19, 1984

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Wright v. United States Steel Corporation Brief of Plaintiffs-Appellees, 1984. f050259d-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/55091011-e69c-44cb-95a9-392c92767869/wright-v-united-states-steel-corporation-brief-of-plaintiffs-appellees. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

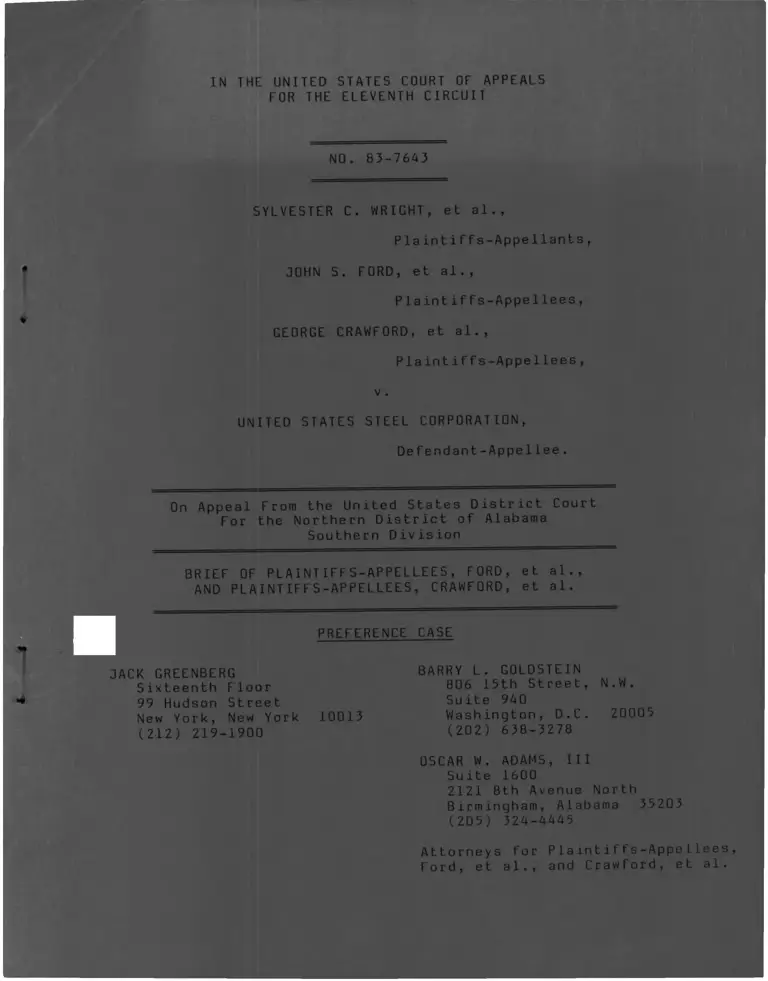

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

NO. 83-7643

SYLVESTER C. W R I G H T , et a l .,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

JOHN S . FORD, et a l . ,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

GEORGE CRAWFORD, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v .

UNITED STATES STEEL CORPORATION,

Defendant-Appellee.

On Appeal From the United States District Court

For the Northern District of Alabama

Southern Division

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES, FORD, et al.,

AND PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES, CRAWFORD, et al.

JACK GREENBERG

Sixteenth Floor

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York

(212) 219-1900

PREFERENCE CASE

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

806 15th Street, N.W.

Suite 940

10013 Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 638-3278

OSCAR W. ADAMS, III

Suite 1600

2121 8th Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

(205) 324-4445

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Ford, et al., and Crawford, et al.

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OP APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

NO. 83-7643

SYLVESTER C. W R I G H T , et al . , )

)

P1 a intiffs-Ap pe11 ants , )

)

JOHN S . FORD, et al . , )

)

P1 a intiffs-Appe1lees , )

)

GEORGE CRAWFORD, et al . , )

)

P1 a intiffs-Appe1lees , )

)

v. )

)

UNITED STATES STEEL )

CORPORATION, )

)

Defendant-Appe11e e . )

CERTIFICATE REQUIRED BY LOCAL RULE 22(F)(2)

The undersigned, counsel of record for p 1 a intiffs-appe1l e e s ,

Ford, et al., and Crawford, et a l ., certifies that the following

persons have an interest in the outcome of this case. These

representations are made in order that the Judges of this

Court may evaluate possible disqualification or recusal:

1. John S. Ford, et al.,

and the class of black

employees at United

States Steel Corpora

tion's Fairfield,

Alabama W o r k s .............. Plaintiffs-Appellees in

Ford v . United States

Steel Corporation

2. George Crawford, et

a l ...........................Plaintif fs-Appellees in

Crawford v . United States

Steel Corporation

3. United States

Steel Co rporation....... Defendant-Appellee

4. Sylvester C. Wright,

et a l .......................Plaint if fs-Appellants

3. Barry L. Goldstein,

Jack Greenberg and

Oscar W. Adams, I I I .......Attorneys for Plaintiffs-

Appellees

6. Thomas, Taliaferro,

Forman, Burr & Murray...Attorneys for Defendant-

Appellee

7. Orzell Billingsley,

J r ........................... Attorney for Plaintiffs-

Appellants

BARRY L. GOLDSTEIN

Counsel of Record for

Plaint iffs-Appellees, Ford, et a l .

and Crawford, et al.

STATEMENT REGARDING PREFERENCE

This appeal involves the parties' rights and obligations

under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended,

42 U.S.C. §2000e e_t seq ., which provides in pertinent part that

"[i]t shall be the duty of the judge ... to assign the case

for hearing at the earliest practicable date and to cause the

case to be in every way expedited." 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(f)(5).

Although this appeal is not listed as a preference appeal in

Appendix One to the Local Rules, p 1 aintiffs-appe11ees submit

that this case merits preference processing.

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT

The back pay provided for in this class action settlement,

the subject of this appeal, was accepted by over 1300 indi

viduals. Only six individuals objected to the settlement. The

back pay was due to be paid prior to Christmas, 1983. The filing

of this appeal has delayed that payment.

It is the considered opinion of pi a intiffs-appe11ees that

this appeal is frivolous. P 1 a intiffs-appe1lees believe that oral

argument in this case is unnecessary, and submit that the judg

ment of the District Court approving the settlement is due to

be .summarily affirmed.

- i i i -

NGTE ON FORM OF CITATIONS

refers to the numbered pages in volume 1 of

the Record on Appeal.

refers to the numbered pages in volume 2 of

the Record on Appeal, the transcript of the

fairness hearing held on October 7, 1983.

refers to the Record Excerpts filed by the

defendant-appe11ee and the p 1 aintiffs-appe11ees .

- I V

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Certificate Required by Local Rule 22(f)(2) 1

Statement Regarding Preference iii

Statement Regarding Oral Argument iii

Note on Form of Citations iv

Table of Contents v

Table of Authorities vi

Statement of the Issues viii

STATEMENT OF THE CASE 1

A . Int roduct ion 1

B. Representation by Plaintiffs' Counsel

and the Role Played by Objectors'

Counsel, Mr. Billingsley. 3

C. Fairness Hearing 8

D. Adequacy of Settlement 11

E. Statement of the Standard of Review 13

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT 14

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION 15

ARGUMENT 15

THE SETTLEMENT IS FAIR, ADEQUATE AND

REASONABLE, AND THE DISTRICT COURT DID NOT

ABUSE ITS DISCRETION IN APPROVING THE

SETTLEMENT. 15

CONCLUSION 19

Certificate of Service

v

TABLE OF AUTH ORITIES

C a s e s : Pages

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S.

405 (1975)............................................... 15

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36

(1974).................................................... 15

Bugg v. Int'l. Union of Allied Industrial Workers

of Am., Local 507, 674 F.2d 595 (7th Cir. 1982). 16

Crawford v. United States Steel Corporation,

660 F . 2d 663 ( 5th Cir. 1 9 8 1 ) ........................ 2

Curtis v. Loether, 415 U.S. 189 ( 1 9 74 ).............. 12

Ford v. United States Steel Corporation,

17 FEP Cases 940 (N.D. Ala. 1 9 7 7 ) ................. 8

Ford v. United States Steel Corporation, 638 F.2d

753 ( 5th Cir . 1981 ).................................... 2, 17

General Telephone Co. v. Falcon, 457 U.S. 147

(1982).................................................... 4, 18

Georgia Ass'n of Retarded Citizens v. McDaniel,

716 F . 2d 1565 ( 11th Cir. 1 9 8 3 ) ...................... 13

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 40. U.S. 424 (1971 )..... 15

Harris v. Plastics Mfg. Co., 617 F.2d 438

(5th Cir. 1 9 8 0 ) ......................................... 17

Holmes v. Continental Can Co., 706 F .2d 1144

(11th Cir. 1983 ) ........................................ 13, 16

Teamsters v. united States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977)... 4, 18

United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries,

63 F.R.D. 1 (N.D. Ala. 1974), a f f 'd ,

517 F.2d 826 (5th Cir. 1975), cert, denied,

425 U.S. 944 (1976).................................... 2

United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries,

517 F . 2d 826 ( 5th Cir. 1975 ) ........................ 2, 19

United States v. N.L.- Industries, Inc., 479 F.2d

334 (8th Cir. 1973 ).................................... 15

- v i -

Table of Authorities (Continued)

Cases :

United States v. United States Steel Corpora

tion, 371 F.Supp. 1045 (N.D. Ala. 1973 )..........

United States v. United States Steel Corpora

tion, 6 EPD para. 8619 (N.D. Ala. 1973 ) ..........

United States v. United States Steel Corpora

tion, 6 EPD para. 8790 (N.D. Ala. 1973 )..........

United States v. United States Steel Corpora

tion, 520 E.2d 1043 (5th Cir. 1975 ), reh . den. ,

525 F . 2d 1214, c e r t . d e n i e d , 429 U.S. 817

(1976 )....................................................

Vuyanich v. Republic National Bank of Dallas,

723 F .2d 1195 (5th Cir. 1 9 8 4 ) .......................

Walker v. Fo rd’Motor Co., 684 F .2d 1355 (11th Cir.

1 9 8 2 ) ............................. •.......................

Statutes and other authorities:

28 U.S.C. § 1 2 9 1 .....................................

42 U.S.C. § 1 9 8 1 .....................................

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (as

amended), 42 U.S.C. §§2000e et s e q ..........

Fed. R. Civ. Proc. 5 2 ( a ) ..........................

- v i i -

Pages

2, 12-13

2

2

2, 17

18

12

15

12

Passim

13

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

!• Whether the District Court abused its discretion in

concluding that the settlement is fair, reasonable, and

adequate, and in entering the consent decree?

2. Whether the contentions raised by the objectors-

appellants are frivolous and that, accordingly, the judgment

of the District Court should be summarily affirmed?

- v i i i -

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

NO. 83-7643

SYLVESTER C. WRIGHT, et al., )

)

PI a intiffs-Appe1lants , )

)

30HN S. FORD, et al . , )

)

P 1 a intiffs-Appe11ees , )

)

GEORGE C R AW FO RD, et al . , )

)

P 1 a intiffs-Appe1lees , )

)

v. )

)

UNITED STATES STEEL )

CORPORATION, )

)

Defendant-Appe11ee . )

ON APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES

DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN

DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

SOUTHERN DIVISION

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A . Introduct ion

On October 7, 1983, Judge Pointer approved a Consent Decree

which, if upheld, will finally end the 18-year litigation concern

ing the racially discriminatory employment practices at United

States Steel Corporation's Fairfield Works. This "sharpiy-contested

employment discrimination case,"-^ involved a trial with "hundreds

of witnesses, more than 10,000 pages of testimony, and over ten

feet of stipulations and exhibits (the bulk being in computer

2/ 3/or summary form,"— three appeals,— and numerous decisions by

the district court. The litigation has resulted in substantial

benefits for the class of black workers at Fairfield Works. In

1973 the district court entered a 130-page Decree which provided

for broad injunctive and affirmative remedies.-7. The class of

black workers received court-awarded back pay amounting to

5 /

$201,000 in 1973,— ; approximately 3,400,000 from the steel indus

try consent decree,— 7, and will receive $586,724.84 from the Con

sent Decree, if it is approved.

The complex litigation history, the process by which the

decree was approved, and scope of the consent decree are fully

described in the Oral Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law,

1 / United States v. United States Steel Co rporation, 520 F.2d 1043,

1047, (5th Cir. 1975), reh. den., 525 F.2d 1214, cert, denied, 429

U.S. 817 (1976).

2/ United States v. United States Steel Corporation, 371 F.Supp.

1045, 1048 (N.D. Ala. 1973). See, R . E . 279 .

2/ United States v. United States Steel Corporation, s u p r a ; Ford

v. United States Steel Corpor at io n, 638 F.2d 753 (5th Cir. 1981);

Crawford v. United States Steel Co rporation, 660 F .2d 663 (5th Cir.

1981).

<4/ S e e , United States v. United States Steel Co rporation, 6 EPD

para. 8619 (N.D. Ala.)

5/ United States v. United States Steel Corporation, 6 EPD para.

8790 (N.D. Ala.)

6_/ See Un ited States v. A1leqheny-Lud1 urn Industries, 6 3 F.R.D. 1

(N.D. Ala. 1974), aff'd, 517 F .2d 826 (5th Cir. 1975), cert, denied,

425 U.S. 944 (1976).

2

R.E. 149-58, the Joint Brief in Support of Pinal Approval of the

Consent Decree which was adopted by the District Court as part

of its findings of fact and conclusions of law,- R.E. 116-48,

and the Brief of Defend ant-Appe1lee United States Steel Corpora

tion. The pi a intiffs-appe11ees will not burden the Court with

a third recitation of the pertinent facts and proceedings.

Rather the plaint iffs-appellees will focus upon the factual and

procedural context of the several assertions made in the Brief sub

mitted by the appel1 ants-objectors. The appellants' arguments,

to the extent which we can discern what these arguments are in

fact, appear to be based on the assertions that plaintiffs' coun

sel did not adequately represent the interests of the class, that

objectors' counsel, Mr. Billingsley, did not receive attorneys'

fees, that the objectors did not have a fair hearing, and that

the amount of the back pay was inadequate.

B . Representation by Plaintiffs' Counsel and the Role

Played by Objectors' Counsel, Mr. Billin gs le y.

The objectors implicitly criticize the representation of the

plaintiff class by their attorneys. First, throughout this litiga

tion the Courts have repeatedly found that the plaintiff class has

7/ Judge Pointer stated that "in approving this settlement [I am]

going to take a rather unusual step because I am going to adopt as

an appendix, an attachment to this order and as findings of fact and

conclusions of law a brief that was submitted jointly by Counsel for

the Plaintiffs and for the Company. I do so because the factual

matters alleged therein are accurate and the statement of the law

is a good statement of the law. It would be ultimately a waste of

effort for me to attempt to duplicate what Counsel have already done

so a b l y ____" R.E. 151.

3

g /

been well represented The District Court referred to "the very

professional attitude of all counsel in expediting the trial"

(footnote omitted), 371 F.Supp., at 1048. In its 1973 opinion,

the Fifth Circuit observed that "the adequacy of the representa

tion [by plaintiffs' Counsel] in this court has been impressive,"

520 F.2d, at 1051, and in its 1981 opinion, the Court observed

that "the representation by the plaintiffs ... seems to be exem-

larly," 638 F.2d, at 761 n.22. In approving the consent decree,

Judge Pointer stated that,

I have not seen as effective representa

tion of a class in any other litigation

as I have over these many years, and

that has not only been so by the attor

ney appearing on behalf of the class

but by many workers who gave assistance

to them and kept in communication with

other members of the class and with the

conditions out at Fairfield.

R.E. 150-51; see a l s o , Tr. 27.

Second, the plaintiffs had to prevail on three separate appeals

to the Fifth Circuit, see n.3, s u p r a , and overcome difficult inter

vening Supreme Court decisions, Teamsters v. United S t a t e s , 431 U.S.

324 (1977 ), and General Telephone Co. v. F a l c o n , 457 U.S. 147 (1982),

8/ The plaintiffs have been represented by a number of attorneys.

Mr. Oscar Adams, Jr., and his partners, U.W. Clemon, and James K.

Baker, represented the plaintiffs since 1966. Mr. Adams, now

Justice Adams, continued to represent the plaintiffs until he was

appointed to the Supreme Court of Alabama in October, 1980.

Mr. Clemon, now Judge Clemon, continued to represent the plaintiffs

until his confirmation as a Federal Judge in June, 1980. Mr. Baker

continued to represent the plaintiffs until he was appointed as the

City Attorney for Birmingham on August 15, 1978. Mr. Oscar W. Adams,

III, has represented the plaintiffs since he joined the firm of

Adams, Baker & Clemon in 1976. Mr. Adams and his partners associated

as co-counsel Jack Greenberg and other attorneys at the NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. Mr. Greenberg has represented the

plaintiffs from 1966 to the present and Mr. Barry Goldstein, another

attorney at LDF, has represented the plaintiffs from 1971 to the present.

4

in order to obtain the relief provided for in the consent decree.

Third, the overwhelming majority of named plaintiffs, 54 out of

56, and class members, 99?o, accepted the settlement and filed no

objections. R.E. 142; U.S. Steel Brief, at 34. Fourth, the

objectors provide no evidence which supports a conclusion that

the class has been inadequately represented.

In their brief,the objectors make several wildly inaccurate

statements concerning this litigation. In their brief, the ob jec

tor s -appe 1 1 an t s assert that the attorney for the objectors was

"involve[d]" in this litigation and that he is entitled to attor

ney fees. The brief refers to no facts in the litigation-^ but

rather states that "the record speaks for itself and the 'proof

is in the pudding.'" Brief, at 11. In fact, the objectors' attor

ney played no role in the proceedings in this litigation which

have led to .the award of a remedy for the class and to the proposed

consent decree. Mr. Billingsley took rm part in the more than

50 days of trial which took place over a six month period in 1972,

took rm part in the three appeals, see n.3, s u p r a , which preserved

the rights of the class members, and took rm part in the remand

litigation and negotiations which led to the proposed consent decree

£/ The objectors' brief refers to two lengthy submissions filed by

Mr. Billingsley which contain newspaper articles, assorted pleadings

in this and other litigation, letters and other documents. See

R. 67-142 and R. 174-214. Regarding these documents Judge Pointer

stated that the filing has "as much junk and garbage in it and is as

little useful as most [any]thing[ ] that I have ever seen ..." Tr.

We do not attempt to characterize this filing other than to borrow a

phrase from the objectors' brief -- "the proof is in the pudding."

26 .

5

Prior to the 1972 trial Mr. Billingsley had at one time

represented black workers in two of the civil actions, Love v.

United States Steel Corpor at io n, Civil Action No. 68-204 and

Brown v. United States Steel Corporation, Civil Action No. 69-

165, which were consolidated for trial. See Tr. 27. Another

attorney, Mr. Richmond Pearson, was substituted as counsel for

Mr. Billingsley prior to trial in 1972. R. 116. After the trial

and after the entry of final judgment on August 10, 1973, Judge

Pointer at the request of Mr. Billingsley entered an order list

ing Mr. Billingsley as "additional counsel" in Love and Brown

but providing that this order "in no way rescinds or invalidates

the prior direction of the court which had substituted, J. Richmond

Pearson for Orzell Billingsley, J r ..... " R. 118. Judge Pointer

referred to this prior history by stating that:

Mr. Billingsley, at one point in this liti

gation you were involved as co-counsel

[in] I believe two of the cases. It is my

observation that if the class members in

this case had been represented by you

rather than by the people who did pursue

the litigation they would have gotten

nothing, and I will just say that very

frankly.

Tr. 27.

The objectors' brief states that "[a]t the insistance of the

attorney Orzell Billingsley, Jr., and others an appeal of the Ford

case was filed on September 10, 1973." This is a pure fabrication.

The procedure for the appeal from the decision denying back pay

to most of the black workers was determined in a chambers confer

ence just prior to the issuance of the injunctive order on May 2, 1973.

6

R.E. 124-25. Judge Pointer expanded the Ford class to include all

those black workers who were employed at Fairfield Works during

the pertinent time period except for those black workers who were

represented in the other private actions, including Love and

B r o w n . R.E. 124 n.7. At the time of the chambers conference,

Mr. Billingsley was not counsel for any party nor was he present

at the conference. Mr. Billingsley did not have any role in the

filing of the appeal in Ford after the entry of Final Judgment on

August 10, 1973, since Mr. Billingsley neither represented the Ford

plaintiffs nor the Ford class. The plaintiffs whom Mr. Billingsley

represented before June 1972 and after October 1973, the Love and

Brown classes, never filed an appeal. Mr. Adams and his co-counsel

never could file an appeal on behalf of the Love and Brown classes

because they did not represent these classes. The Ford class

definition specifically excluded the members of these classes.

Since the entry of a Final Judgment in the Brown and Love

cases in 1973 and during the continued litigation of the Ford case,

Mr. Billingsley has intermittently sought an award of attorneys fees

» through varied procedural routes. In 1974 Mr. Billingsley sued cl aim

ing $300,000 in damages from Oscar Adams, Jr., and from the law firm

of Adams, Baker, & d e m o n , "for falsely and maliciously removing the

name of the plaintiff, Orzell Billingsley, Jr. ..." R. 132-33. The la w

suit was dismissed by Judge McFadden. R. 71-72. In 1977 on behalf of

Mr. Brown and Mr. Love, Hr. Billingsley filed a "Motion to Reconsider

and/or Amend and/or Modify and/or Reopen Judgment." R. 135-39. The

Motion sought $500,000 in back pay, $500,000,000 in punitive damages,

7

and "reasonable attorney's fees, not based on hours of work, but

on service rendered...." R. 139. On July 22, 1983, Mr. Billingsley

filed a "Claim for Attorney Fees and Expenses" in Ford and

Craw fo rd. R. 67-68. Finally, on this appeal, the objectors raise

as their third issue "[wjhether the Court erred in denying the

attorney [Mr. Billingsley] for the Appellants' [sic] attorney

fees and expenses," Brief, at 1; see Brief, at 10-11.

The objectors state that "[t]he attorneys [for the plaintiff

class] asked for more in attorneys fees than they requested in

back pay." This assertion shows a reckless disregard for the

truth. Counsel for the plaintiffs and for the defendants

net

represented to the Court "that they/did negotiate, much less

reach, any agreement as to attorneys' fees." R.E. 143. Further

more, the.consent decree provides that "[a]ny agreement as to

fees or costs must be submitted to [the] Court for approval."

R.E. 42.— /

C . Fairness H e a r i n g .

The objectors asserted that the fairness hearing and the review

of the consent decree afforded by the Court were improper. Brief,

at 7-9. The objectors argue that there was a "hurried hearing",

that "[n]o live witnesses were available", and that there was no

10/ The plaintiffs' attorneys have waited for the approval of the

consent decree before negotiating for or seeking attorneys' fees.

The plaintiffs' attorneys have maintained this position even though

the Court in 1977 stated that in the appeal from the denial of back pay

plaintiffs, by their counsel, succeeded in reversing a ruling denying

back pay.... As to this part, the plaintiffs certainly prevailed and,

in t h e c o u r t ' s discretion, should be awarded attorney's fees." Ford

v * United States Steel Co rporation, 17 FEP Cases 940, 944 (N.D. A l a . ) .

8

"statistican or economist." Brief, at 7. However, the objectors'

assertions completely misstate the record as the following exchange

between counsel for plaintiffs and the Court indicates:

[Counsel]: ... I don't know of a case

that has a more extensive record than

the record in this particular litiga

tion.

The Court: Well, certainly this is

not a situation where the Court is

called upon to decide whether to approve

the settlement with very little infor

mation.... As you indicate, I have

been rather intimately involved with

this litigation for over ten years,

including trial and further reviews....

Tr. 8-9, see also R.E. 149. Furthermore, the findings of fact

and conclusions set forth the detailed evidence available to the

Court. See, R.E. 135-41.

The objectors state they "were unfairly given the burden of

showing the agreement not to be fair, reasonable and adequate.

This misinterpretation clearly violates due process and is a

reversible error." Brief, at 9. Again the objectors misstate

the record. The Court stated that "[t]he responsibility of the

Court at this point is to determine in the light of what has been

presented to me both by those who support this settlement and by

those who have taken objection or exception to it whether it is

fair and reasonable and adequate bearing in mind the interest of

the class as a whole." R.E. 149; see a l s o , R.E. 132. The Court

summarized why "the interests of the class as a whole" requires

the approval of the consent decree:

9

It is now almost ten years from that

date [entry of Steel Industry Consent

Decree], over ten years from the date

of the original trial, and then

prospects are that if this litigation

continues it will involve, I would say,

a minimum of five years of additional

litigation. No one can say precisely

what the outcome of that litigation

would be.

R.E. 150. The objectors did not present any argument at the

fairness hearing or submit any evidence nor do they in their

brief which indicates that the "interests of the class as a

whole" would be best served by disapproval of the consent decree.

Finally, the objectors state that an individual "was abruptly

threatened with arrest by the U.S. Marshall," Brief, at 3, and

the threatening of [the individual] with confinement in jail

could have intimidated and frightened some of the claimants....,"

Brief, at 7. The published notices, personnel notices, and

detailed notices all made it clear that a class member would have

to file a written objection by July 22 in order to have his

objection considered. See,R.E. 60, 68, 81. The Court inquired

as to whether any of the six persons who filed objection "would

like to ... supplement the objections." Tr. 10. After hearing

from the objectors,counsel for the objectors, and counsel for

the plaintiffs, Tr. 10-30, the Court asked whether "there [is] any

other comment or question," Tr. 31. After hearing from a number

of individuals and answering several questions, Tr. 31-41, the Court

announced that it was "going to take a recess of ten minutes and

return at that time arvd make a decision of whether to approve or

not the settlement." Tr. 41.

10

After the Court returned and rendered its decision,

Mr. Mathis (or Mr. Brasher as identified in the transcript)

requested the opportunity to ask a question. Tr. 50. The Court

responded "[s]urely." I d . Mr. Mathis did not ask a question

but rather asserted his view of how back pay should be calculated

— "If he [a white worker] made $66,000, I made 23, you ought

to subtract 23 from 66 and put the rest in my pocket." Tr. 51-52.

The Court stated that "I appreciate your comment" and

responded to Mr. Mathis in some detail. Tr. 52-53. Mr. Mathis

sought to continue the argument. The Court stated that "You may

be seated. The Marshall will get the gentlemen unless you are

willing to be seated." Tr. 53. The Marshall simply stated ” [b]e

seated, please." I d . In fact, the Court showed enormous solici

tude for the views of class members even if the class members did

not file objections and even if those views were made after the

Court rendered its opinion. There was no "threat[ ] of confine

ment in jail" or "threat[ ] of arrest by the U.S. Marshall" as

baldly stated by objectors.

D . Adequacy of Settlment.

In their brief, the objectors disparage the amount of the

settlement. For example, the objectors refer to "mere pennies for

a settlement," and that "[t]he settlement was not even a 'good no

fault settlement,'" Brief, at 10. The objectors provide no ev i

dence or analysis in support of their rhetoric. The only argument

supplied by the objectors is that "in view of all of the circum

stances, [it is] possible that the Objectors ... are now entitled

11

to punitive damages. Brief, at 2; see Brief, at 10.

The objectors fail to explain how they could obtain punitive

damages under Title VII when this Court, and every other Circuit

Court which has ruled on the issue, have determined "that compensa

tory and punitive damages are unavailable in Title VII suits."

Walker v. Ford Motor C o ., 684 F.2d 1355, 1364 (1982). Even if

the objectors could somehow avoid the legal bar, perhaps under

4 2 U.S.C. §1981,-^-// the objectors have set forth no "circumstances

which would meet the burden for entitlement to punitive damages.

In fact, the law of the case established by Judge Pointer's 1973

opinion would undercut any claim to punitive damages.

In the early 60's [before the effective

date of Title VII and before any period

which would be covered by a §1981 action],

however, largely in response to Executive

Order 10925 ... nondiscrimination became

the announced official policy at the

works .

* * * * * *

The point is that, while the 1962-63

changes represented a truly radical

alteration in the unemployment practices

at Fairfield, some passage of time was

needed for these processes to begin

transforming the statistical profile....

It is clear that on July 2, 1965,

the effective date of Title VII, the

basic principles of the seniority system

11/ Of course, if the objectors sought punitive or compensatory

damages then the defendants would be entitled to a jury trial.

Curtis v. L o e t he r, 415 U.5. 189 (1974). The presentation of these

complicated issues of systemic race discrimination- to a jury would

seriously effect any chance which the plaintiffs might have to pre

vail on the merits.

12

in effect at Fairfield were not "actively"

discriminatory. (Footnotes omitted)

United States v. United States Steel Corpor at io n, 371 F.Supp.,

at 1033. The Court found that the settlement is "favorable and

reasonable ... considering the interest of the class as a

whole...." R.E. 151. The Court had access to a substantial

record, see section C, s u p r a , and was "personally ... familiar

with most of the things that have occurred in this litigation

since 1971." R.E. 149. The Record supports the findings of

the Court that the settlement was reasonable and favorable. See,

R.E. 135-41.

E • Statement of the Standard of R e v i e w .

"In reviewing the validity of a class action settlement, a

district court's decision will be overturned only upon a clear

showing of abuse of discretion." Holmes v. Continental Can Co.,

706 F . 2d 1144, 1147 (11th Cir. 1983). In determining whether the

District Court abused its discretion in concluding that the set

tlement was reasonable, the District Court's findings of fact should

be upheld unless clearly erroneous. Fed. R. Civ. Proc. 52(a).

Georgia Ass'n. of Retarded Citizens v. M c D a n i e l , 716 F . 2d 1565,

1573-74 (11th Cir. 1983).

13

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

The litigation concerning discriminatory employment prac

tices at U.S. Steel's Fairfield Works commenced in 1966.

Judge Pointer, who approved the consent decree, presided over

a lengthy trial during which the discriminatory practices were

reviewed in great detail. Under these circumstances, the conclu

sion of the lower court that the settlement was "favorable" and

"reasonable" should be afforded substantial regard and the Court

should be particularly reluctant to find a clear abuse of discre

tion by the lower court in approving the settlement.

The objectors-appellants filed a "perfunctory brief" which

did not provide any arguable reason for even questioning the lower

court's judgment. If the consent decree is not approved, there is

a substantial likelihood that many members of the class, who are

now entitled to receive a share of the monetary relief, will not

receive any remedy. Accordingly, the decision of the lower court

should be summarily and promptly affirmed.

14

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

This is an appeal from a final judgment of a district court

brought pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §1291.

ARGUMENT

THE SETTLEMENT IS FAIR, ADEQUATE AND

REASONABLE, AND THE DISTRICT COURT DID NOT

ABUSE ITS DISCRETION IN APPROVING THE SETTLEMENT.

"The objective of Congress in the enactment of Title VII ...

was to achieve equality of employment opportunities and remove

barriers that have operated in the past to favor an identifiable

group of white employees over other employees." Griggs v. Duke

Power C o ., 401 U.S. 424, 429-30 (1971). Congress selected

"[c ]ooperation and voluntary compliance ... as the preferred means

of achieving this goal," Alexander v. Gardner-Denver C o . , 415 U.S.

36, 44 (1974), but further recognized that the imposition of judi

cial remedies were "the spur or catalyst which causes employers

and unions to self-examine and to se1 f-evaluate their employment

practices and to endeavor to eliminate, so far as possible, the

last vestiges of an unfortunate and ignominious page in this coun

try's history." Albemarle Paper Co. v. M o o d y , 422 U.S. 405, 417-18

(1975), quoting United States v. N. L. Industries, Inc., 479 F.2d

334, 379 (8th Cir. 1973).

This employment litigation regarding Fairfield Works reflects

all aspects of these fundamental policies. Judge Pointer presided

over a hotly contested and lengthy trial which resulted in the

judicial imposition of a substantial remedy. See pp. 1-2, s u p r a ;

15

R. E. 121-23. The decision served as a "catalyst" for the

nation-wide, Steel Industry Consent Decree which provided fur

ther relief to black workers at Fairfield Works. R.E. 124-26.

After the entry of the Steel Industry Consent Decree, the plain

tiffs continued to litigate on behalf of the remaining class of

black workers both before the District Court and on three separate

occasions on appeal. See p.2, s u p r a ; R.E. 127-31. This entire

litigation spurred the final settlement of this litigation.

Judge Pointer has been "intimately involved with this litigation

for over ten years." Tr. 9, see R.E. 149.

Under these circumstances, the decision of Judge Pointer, who

has been so closely involved in this complex litigation, should be

given substantial regard and the Court should be particularly

reticent to overturn that decision by finding "a clear ... abuse

of discretion." Holmes v. Continental Can C o ., 706 F.2d, at 147.

Moreover, there is absolutely no basis for raising even a question

regarding the validity of the Court's decision much less showing

that the Court clearly abused its discretion. The record fully

supports the Court's conclusion that the settlement is "favorable"

and reasonable" as is set forth in the Court's oral opinion, R.E. 149

38, and in the findings of fact and conclusions of law. R.E. 118-

47. Furthermore, as set forth in the Statement of the Case, the

objectors "in a perfunctory brief, [have] failed to present any

arguable reason why the district court erred in its disposit i o n ."

9, v • Int'l Union of Allied Industrial Workers of Am., Local 3 0 7 ,

16

674 F.2d 595, 600 (7th Cir. 1982); s e e , Harris v. Plastics Mfq.

Co • , 617 F .2d 438, 440 (5th Cir. 1980).

Approximately 1300 individuals are waiting for the distribution

of the settlement funds. Seven individuals have filed this appeal.

These objectors have stated no reason why the considered ju dg

ment of the lower court should be overturned. Under the circum

stances, the decision of the lower court should be summarily and

promptly affirmed.

The findings of fact and conclusions of law describe in

detail the facts and law supporting the approval of the consent

decree. The defendant-appe1lee United States Steel Corporation

has described the argument in support of the consent decree in

further detail. U.S. Steel Brief, at 31-48. There is no need to

state further these arguments.

In conclusion, it is important to emphasize how critical the

approval of this settlement is to the class members. As a prac

tical matter, if this consent decree is not approved it is likely

that a large majority of those class members who are now entitled

to monetary relief will receive nothing. First, the class issues

in this litigation are enormously complex as exemplified by the fact

that this Court has vacated and remanded the district court's certi

fication of a class, Un ited States v. United States Steel Co rporation,

520 F.2d 1043 (1975), and failure to certify a class, Ford v. United

States Steel Co rporation, 638 F .2d 753 (1981). It is possible that

many black workers who are currently members of the class and

entitled to relief would not even be members of the class if the

17

issue was litigated to conclusion. This possibility was increased

by a recent decision of the Supreme Court, General Telephone

Company v. F a l c o n , 457 U.S. 147 (1982), which narrowed the appli

cation of the class action rule to Title VII actions. See e.g.,

Vuyanich v. Republic National Bank of D a l l a s , 723 F.2d 1195

(5th Cir. 1984); see a l s o , R.E. 135-36 and Tr. 22-23 .

Moreover, there is substantial doubt that the plaintiffs

could prevail on the major liability issue -- that the seniority

systems in the nine plants, scores of departments, and huncreds

of lines of promotions at Fairfield Works were created or ma in

tained with an intent to discriminate. See Teamsters v. United

St a t e s , s u p r a ; R.E. 136-38; Tr. 20-22,

In light of Teamsters and the factual

maze presented at Fairfield Works the

[plaintiffs] faced a considerable

task in even fully presenting the

seniority issue to the Court and c e r

tainly faced considerable risk that

the determination of the legality

systems, or at least the determination

with regard to a substantial part of

the system, would be adverse to their

interests.

R.E. 138.

Furthermore, even if the plaintiff class prevailed on the

class action and liability issues, it is likely that relatively

few would actually receive back pay benefits because, in general,

there were many more class members than vacancies during the

pertinent time period in any particular department or line of promo

tion. R.E. 139-41. As this Court observed with respect to those

small, private classes who were awarded back pay by the District

18

Court, 298 of the 359 members in those classes did not receive

any back pay because there were many fewer job vacancies -- and

thus opportunities for discrimination -- than there were class

members. United States v. Alleqheny-Ludlum Industries, In c . ,

517 F.2d, at 863-64 n.47. Finally, even if the plaintiff class,

or part of the class prevailed on all issues, the additional

litigation in this complicated case would take, as Judge Pointer

concluded, "a minimum of five years." R.E. 150. Given the age

of the class, the additional wait for relief would result, in

many instances, in any remedy going to the heirs of class members

and not to the class members.

CONCLUSION

Thus, the Court should promptly and summarily affirm the judg

ment of the district court approving the consent decree.

Respectfully submitted,

BARRY L . GOLDSTEIN

806 15th Street, N.W.

Suite 940

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 638-3278

OSCAR W. ADAMS, III

Suite 1600

2121 8th Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

(205) 324-4445

JACK GREENBERG

Sixteenth Floor

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees,

Ford, et a l ., and Crawford, et a l .

19

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that a copy of the Brief of Plaintiffs-

Appellees Ford, et al., and Crawford, et al., was served on

counsel for all parties as set forth below by placing the copy

postage prepaid in the United States mail on this 19th day of

A p r i l , 1984:

William K. Hurray

1600 Bank for Savings Building

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

S. G. Clark, Or.

600 Grant Street

Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15230

Orzell Billingsley, Or., Esq.

1630 4th Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Jerome A. Cooper, Esq.

Cooper, Mitch & Crawford

409 North 21st Street

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

13