Report to the Court

Public Court Documents

April 10, 1989

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Chisom Hardbacks. Report to the Court, 1989. 456d2500-f411-ef11-9f8a-6045bddc4804. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5526fc16-0a32-42ad-aaab-a87ea2a08791/report-to-the-court. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

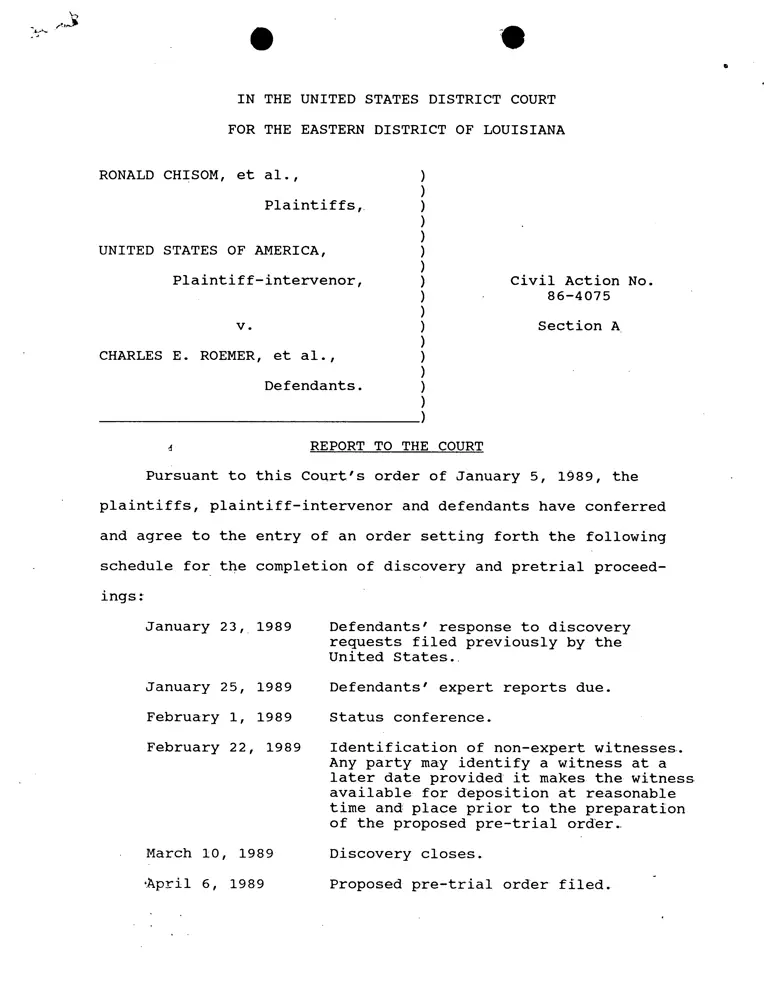

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

RONALD CHISOM, et al.,

Plaintiffs,

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

Plaintiff-intervenor,

V .

CHARLES E. ROEMER, et al.,

Defendants.

Civil Action No.

86-4075

Section A

4 REPORT TO THE COURT

Pursuant to this Court's order of January 5, 1989, the

plaintiffs, plaintiff-intervenor and defendants have conferred

and agree to the entry of an order setting forth the following

schedule for the completion of discovery and pretrial proceed-

ings:

January 23, 1989

January 25, 1989

February 1, 1989

February 22, 1989

March 10, 1989

.April 6, 1989

Defendants' response to discovery

requests filed previously by the

United States.

Defendants' expert reports due.

Status conference.

Identification of non-expert witnesses.

Any party may identify a witness at a

later date provided it makes the witness

available for deposition at reasonable

time and place prior to the preparation

of the proposed pre-trial order.

Discovery closes.

Proposed pre-trial order filed.

April 10, 1989 Pre-trial conference.

We further agree that written discovery requests and re-

quests for production of documents filed following the entry of

this order will be subject to the provisions of this Court's

order of September 2, 1988, which require that responses to such

discovery shall be filed within fifteen (15) days after service.

We also note that defendant intervenor Calogero's interest

lies in remedy and he had disclaimed any interest in the proceed-

ings on liability.

Respectfully submitted,

For the plaintiffs, Ronald Chisom, et al.:

(2e:10!-01

/JUDITH REED

1" Legal Defense Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

212/219-1900

For the plaintiff-intervenor, United States:

ROBERT S. BERMAN

Attorney, Voting Section

Civil Rights Division

Department of Justice

P.O. Box 66128

Washington D. C. 20035-6128

202/724-3100

For the Defendants, Charles Roemer, et al.:

4y1,7

ROBERT G. PUGH, Te I.D. 33-6—

Pugh and Pugh

330 Marshall Street

Suite 1200

Shreveport, LA 71101

318/227-2270