Louisville Black Police Officers Organization Inc. v. City of Louisville Brief

Public Court Documents

May 13, 1978

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Louisville Black Police Officers Organization Inc. v. City of Louisville Brief, 1978. 6a7cc5f2-bb9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5562b87f-d778-4b86-ad05-163fe1181ddb/louisville-black-police-officers-organization-inc-v-city-of-louisville-brief. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

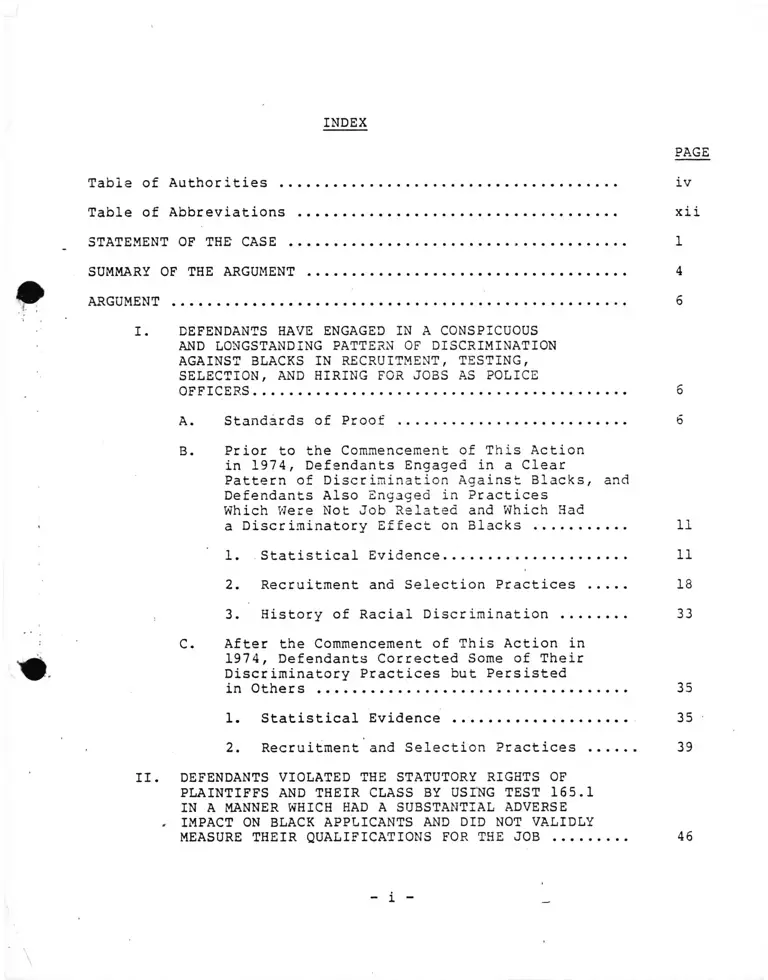

INDEX

Table of Authorities ........................................ iv

Table of Abbreviations ...................................... xii

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ........................................ 1

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT ...................................... 4

ARGUMENT ....................................................... 6

I. DEFENDANTS HAVE ENGAGED IN A CONSPICUOUS

AND LONGSTANDING PATTERN OF DISCRIMINATION

AGAINST BLACKS IN RECRUITMENT, TESTING,

SELECTION, AND HIRING FOR JOBS AS POLICE

OFFICERS............................................. 6

A. Standards of Proof ........................... 6

B. Prior to the Commencement of This Action

in 1974, Defendants Engaged in a Clear

Pattern of Discrimination Against Blacks, and

Defendants Also Engaged in Practices

Which Were Not Job Related and Which Had

a Discriminatory Effect on Blacks ........... 11

1. Statistical Evidence..................... 11

2. Recruitment and Selection Practices ..... 18

3. History of Racial Discrimination ......... 33

C. After the Commencement of This Action in

1974, Defendants Corrected Some of Their

Discriminatory Practices but Persisted

in Others ..................................... 35

1. Statistical Evidence .................... 35

2. Recruitment and Selection Practices ...... 39

II. DEFENDANTS VIOLATED THE STATUTORY RIGHTS OF

PLAINTIFFS AND THEIR CLASS BY USING TEST 165.1

IN A MANNER WHICH HAD A SUBSTANTIAL ADVERSE

. IMPACT ON BLACK APPLICANTS AND DID NOT VALIDLY

MEASURE THEIR QUALIFICATIONS FOR THE JOB ......... 46

PAGE

PAGE

A. The Applicable Law .......................... 46

B. As Used by Defendants, Test 165.1

Had a Substantial Adverse Impact on Black

Applicants .................................... 50

C. Defendants Have Not Demonstrated That

Test 165.1 Is Manifestly Related to

Performance of the Job of a Louisville

Police Officer ................................ 53

1. Test 165.1 has not been shown to be

content valid for use in selecting

police officers .......................... 55

a. Test 165.1 purports to measure

intellectual constructs rather

than observable work behaviors ..... 56

b. Test 165.1 is not a sample or

approximation of job behavior but

merely a verbal representation

of some parts of a highly physical

and personal job ..................... 62

c. . Test 165.1 involves knowledges,

skills, and abilities which new

police officers are expected to

learn in recruit school or on

the job ............................... 66

d. Test 165.1 represents neither a

critical work behavior nor work

behaviors which constitute most

of the important parts of the job ... 69

2. Test 165.1 has not been shown to have

criterion-related validity for use in

selecting police officers ................ 75

a. Test 165.1 involves knowledges,

skills, and abilities which

incumbent police officers have

' learned in recruit school or on

the job ............................... 76

IX

PAGE

b. The sample subjects were not

representative of actual applicants

for the job .......................... 79

c. Test 165.1 has not been shown to

measure fairly any differences in

the job performance of blacks and

whites ................................ 82

d. The concurrent validity study produced

an odd patchwork of results which did

not demonstrate that Test 165.1 is

valid for use in selecting police

officers in every city ............. 88

3. The validity studies offered by defendants

do not support the use of Test 165.1

in selecting Louisville police

officers .................................. 91

4. Defendants substantially increased the

adverse impact of Test 165.1 by setting

an arbitrarily high passing point and

by improperly using the test to rank

applicants ................................ 95

D. Alternative Selection Procedures with Less

Adverse Impact Would Properly Serve the Defendants'

Legitimate Interest in the Selection of Capable

Police Officers ................................ 100

III. THE COURT HAS THE POWER AND THE DUTY TO FASHION

RACE-CONSCIOUS NUMERICAL HIRING RELIEF WHICH

WILL MAKE THE LOUISVILLE POLICE FORCE MORE

REPRESENTATIVE OF THE COMMUNITY IT SERVES ....... 104

IV. PLAINTIFFS ARE ENTITLED TO AN INTERIM AWARD OF

REASONABLE ATTORNEYS' FEES ....................... 118

CONCLUSION ................... 121

- iii -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Afro American Patrolmens League v. Duck, 503 F . 2d

294 (6th Cir. 1974) ................................ 12,15,39

Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975) . 9,21,46,48,

49,76,79,80,82,

84,85,91,100,

103,104

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36 (1974) ... 10

Associated General Contractors of Mass., Inc. v.

Altshuler, 361 F.Supp. 1293 (D. Mass. 1973),

aff'd. 490 F .2d 9 (1st Cir. 1973), cert, denied,

416 U.S. 957 ( 1974 )................................. 105

Arnold v. Ballard, 390 F.Supp. 723 (N.D. Ohio 1975),

aff'd 12 FEP cases 1613 (6th Cir. 1976), vac.

and rem. on other grounds, 16 FEP cases 396

(6th Cir. 1976) .................................... 40,105,108,114,

116,117

Baker v. Columbus Municipal Separate School District,

462 F . 2d 1112 (5th Cir. 1972) ..................... 8

Boston Chapter, NAACP, Inc. v. Beecher, 504 F . 2d

1017 (1st Cir. 1974), cert, denied, 421 U.S.

910 (1975) .......................................... 24,47,54,64,69,

81,82,95,99,

105,116

Bradley v. Richmond School Board, 416 U.S.

696 (1974 )..................................... ..... 118,119,120

Bridgeport Guardians, Inc. v. Bridgeport Civil

Service Commission, 482 F.2d 1333 (2nd Cir.1973),

cert, denied, 421 U.S. 991 ( 1975) ................. 24,46,49,52,

99,105,106,108,

114,116

Brown v. Board of Education 347 U.S. 483 (1954) ........ 35

Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482 ( 1977) ..... ■........ 16,17,25,45

Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir. )• (en banc) ,

cert, denied, 406 U.S. 950 ( 1972) ................. 105,106,116

Castro v. Beecher, 459 F .2d 725 (1st Cir. 1972)..;.... 47

- iv -

PAGE

Chandler v. Roudebush, 13 CCH E.P.D. <[11,574

(C.D. Cal. 1977 ).................................... 119

Christiansburg Garment Co. v. EEOC, 434

U.S. 412 ( 1978) .................................... 118

Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v. O'Neill, 14

CCH E.P.D. 117699 (E.D. Pa. 1977) ................. 119

Contractors Association of Eastern Pennsylvania v.

Secretary of Labor, 442 F .2d 159 (3rd Cir.

1971), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 854 ( 1971) .......... 106

Crockett v. Green, 534 F .2d 715 (7th Cir. 1976) ........ 15,106,116

Davis v. County of Los Angeles, 566 F .2d 1334

(9th Cir. 1977), cert, granted, 46 U.S.L.W.

3780 (June 19, 1973) ................................ 10,15,21,46,

105,106,108,

116

Dothard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 321 ( 1977 ) .............. 9,46

Douglas v. Hampton, 512 F .2d 976 (D.C. Cir. 1975) ..... 48

Dozier v. Chupka, 395 F.Supp. 836 (S.D. Ohio 1975) .... 21

EEOC v. Detroit Edison Co., 515 F .2d 301 (6th Cir.

1975 ) vac, and rent, on other grounds, 431

U.S. 951 ( 1977) ..................................... 15,47,99,,105,

107,116

Ensley Branch, NAACP v. Seibels, 14 FEP cases 670

(N.D. Ala. 1977) ... ................................ 49

Erie Human Relations Commission v. Tullio, 493 F .2d

371 (3rd Cir. 1974 ) ................................. 105,106,108 ,

116

Feeney v. Massachusetts, ___ F.Supp.___, 17 FEP

Cases 659 (D. Mass. 1978) .............. ............ 8

Firefighters Institute for Racial Equality v. City

of St. Louis, 549 F.2d 506 (8th Cir. 1977),

cert, denied, 434 U.S. 819 ( 1977 ) ................. 47,73,74,100

Fitzpatrick v. Bitzer, 427 U.S. 445 (1976 ) ............. 118

Foley v. Connelie, 55 L.Ed.2d 287 (1978) .............. 109,112

v

PAGE

Furnco Construction Corp. v. Waters, 46 U.S.L.W..

4966 (June 29, 1978)................................ 38

Gregory v. Litton Systems, Inc., 472 F.2d 631

(9th Cir . 1972)..................................... 21

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) .......... 8,9,21,

46,48,49,

103

Harkless v. Sweeny Independent School District,

554 F.2d 1353 (5th Cir. 1977), cert. denied,

434 U.S. 966 (1977)................................. 8,35

Hazelwood School District v. United States, 433

U.S. 299 (1977) ..................................... 9,12,13,14,16,

17,39

Hutto v. Finney, 46 U.S.L.W. 4817 (June 23, 1978)..... 118

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United 9,12,13,14,15,

States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977) ........................ 17,35,38,39,

115,120

James v. Stockham Valves & Fittings Co., 559

F.2d 310 (5th Cir. 1977), cert, denied

434 U.S. 1034 ( 1978) ............................... 118,119,120

Jenkins v. United Gas Coro., 400 F .2d 28

(5th Cir. 1968 ) .......................... ......... 37,40 '

Johnson v. Pike Corp., 332 F.Supp. 490 (C.D.

Cal. 1971)............................ '.............. 21

Johnson v. Ryder Truck Lines, Inc., 15 CCH

E.P.D. H7969 (W.D.N.C. 1977).'.... .............. 119

Johnson v. Ryder Truck Lines, Inc., 575 F.2d 471

(4th Cir. 1978) ......................... ;.......... 10,21 '

Jones v. Tri-County Electric Cooperative, Inc.,

512 F . 2d 1 (5th Cir. 1975 ) ........................ 40

Kirkland v. New York State Dept, of Correctional

Services, 374 F.Supp. 1361 S.D.N.Y. 1974,

aff'd in pertinent part, 520 F.2d 420 (2nd

Cir. 1975), cert, denied, 429 U.S. 974 (1976) .... 47,73,

97,99

vi

PAGE

League of United Latin American Citizens v.> City

of Santa Ana, 410 F.Supp. 873 (C.D. Cal.1976) ..... 12,14,25,40,

79,81,107,

116

Lewis v. Philip Morris, Inc., 13 CCH E.P.D. 1(11,350

(E.D. Va. 1976)..................................... 119

Local 53, Asbestos Workers v. Vogler, 407 F .2d

1047 (5th Cir. 1969) ............................... 106

Long v. Ford Motor Co., 496 F .2d 500 (6th Cir.1974) .... 10

Louisiana v. United States, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) ...... 104

McBride v. Delta Air Lines, Inc., 551 F .2d 113

(6th Cir.), vac. and rem. on other grounds,

434 U.S. 916 (1977) ................................ 7

McLaughlin v. Florida, 379 U.S. 184 ( 1964 ) .......... 35

Mills v. Electric Auto-Lite Co., 396 U.S.

375 (1970) .......................................... 119

Morrow v. Crisler, 479 F .2d 960 (5th Cir.1973),

mod. on reh. en banc on other grounds,

491 F . 2d 1053 ( 5th Cir. 1974 )...................... 12

Morrow v. Crisler, 491 F.2d 1053 (5th Cir. 1974)

(en banc), cert, denied, 417 U.S. 895 (1974) .... 106

NAACP v. Allen, 493 F .2d 614 (5th Cir. 1974) .......... 105,106,108,

114,116

NAACP v. Lansing Board of Education, 559 F .2d 1042

(6th Cir. 1977) .................................... . ' 7,10,19^

Officers for Justice, NAACP v. Civil Service

Commission of San Francisco, 371 F.Supp.

1328 (N.D. Cal. 1973 ) ....................,....... . . 15,108,114

Parham v. Southwestern Bell Telephone Co., 433

F.2d 421 (8th Cir. 1970)........................... 38

Patterson v. American Tobacco Co., 9 CCH

E.P.D. 1(10,039 (E.D. Va. 1975) ............ ....... 119

Vll

PAGE

Pennsylvania v. Flaherty, 404 F.Supp. 1022

(W.D. Pa. 1975) ..................................... 15

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke,

46 U.S.L.W. 4896 (June 28, 1978) .................. 34,85,86,88,

106

Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967) ................. 35

Rice v. Gates Rubber Co., 521 F .2d 782

(6th Cir. 1975)..................................... 38

Rich v. Martin Marietta Corp., 522 F .2d 333

(10th Cir. 1975) ................................... 38

Rios v. Enterprise Association Steamfitters

Local 638, 501 F.2d 622 (2nd Cir. 1974) ........... 106

Rogers v. International Paper Co., 510

F.2d 1340, vacated & remanded on other qrounds,

423 U.S. 809 (1975) .... ......................... 85,S7

Rowe v. General Motors, 457 F .2d 348 (5th Cir. 1972) ... 26,45

Sangmeister v. Woodard, 565 F .2d 460 (7th Cir. 1977) ... 8

Sherrill V. J.P. Stevens & Co., 551 F .2d 308, 13

E.P.D. 1111,422 (4th Cir. 1977) ..................... ... 106

Shield Club,v. City of Cleveland, 13 FEP cases 1373

(N.D. Ohio 1976') ... ................................. 8

Shield Club v. City of Cleveland, 13 FEP cases 1394

(N.D. Ohib 1976 ) . .'.................................. 3

Sims v. Sheet Metal Workers Local 65,. 489 F . 2d

1023 (6th Cir. 1973 ) ........... ..................... 105

Southern Illinois Builders Association v. Ogilvie,

471 F . 2d 680 (7th Cir. 1972) ................. ..... 106

Stamps v. Detroit Edison Co., 365 F.Supp. 87 (E.D.

Mich. 1973) ............... '......... ................. 15,99,107,

116

Stewart v. General Motors Corp., 542 F.2d 445

(7th Cir. 1976), cert, denied, 433 U.S. 919

(1977) ............................................... 25,45

- viii -

PAGE

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303 (1879)

United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburgh v.

Carey, 430 U.S. 144 (1977) ...............

United States v. City of Chicago, 549 F .2d 415

(7th Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 434 U.S.

875 (1977) .................................

United States v. City of Chicago, 573 F.2d 416

(7th Cir. 1978) .....................................

U.S. v. Georgia Power Co, 474 F.2d 906

(5th Cir. 1973) ....................................

United States v. Ironworkers Local 86, 443 F .2d

544 (9th Cir.), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 984 (1971)..

United States v. Local 38, IBEW, 428 F .2d 144

(6th Cir.), cert. denied, 400 U.S. 943 ( 1970).....

United States v. Local 212, IBEW, 472 F .2d 634

(6th Cir. 1973 ) .............. ......................

United States v. Masonry Contractors Association,

497 F . 2d 871 (6th Cir. 1974) ................ .......

United States v. N.L. Industries, Inc., 479 F .2d

354 (8th Cir. 1973) .................................

United States v. .Texas Education Agency, 564 F . 2d

162 (5th Cir. 1977) .................................

United States v.' Wood Lathers Local 46, 471 F . 2d 408

(2nd Cir.)., cer t. denied, 412 U.S. 939 (1973) ....

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan

Housing Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252 (1977) ....

Vulcan Society v.. Civil Service Commission, 490 F .2d

387 (2nd Cir. 1973) .............. ..................

Vulcan' Society v. N.Y. Civil Service Commission,

360 F.Supp. 1265 (S.D.N.Y. 1973), aff'd in

relevant part, 490 F.2d 387 (2nd, Cir. 1973) ......

35

35

21,47,48,52,

54,73,83,85,

105,106,116,

117

9,54,73

48,85,95

106

105

105

105

106

7

106

6,7,8,35

54

52,73,75

IX

PAGE

Wallace v. Debron Corp., 494 F .2d 674 (8th Cir.

1974) .............................................. 21

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) ............... 6,7,8,10,12,

25

Western Addition Community Organization v. Alioto,

360 F.Supp. 733 (1973), appeal dismissed,

514 F.2d 542 (9th Cir. 1975), cert, denied,

423 U.S. 1014 ( 1975) ................................ 99

Yick Wo. v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 ( 1886 ) ............... 35

Constitutional Provisions, Statutes and Regulations

United States Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment ...... passim

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§§2000e et seq....................................... passim

Civil Rights Attorneys' Fees Awards Act of 1976,

Pub. L. No. 94-559, 90 Stat. 2641,

codofied in 42 U.S.C. §1988 ........................ 118,119

42 U.S.C. §1981 ........................................... passim

42 U.S.C. §1983 ........................................... passim

Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection

Procedures (1978), 43 Fed. Reg. 38290

(Aug. 25. 1978) .......................... 25,47-103

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Guidelines

on Employee Selection Procedures,

29 C.F.R. §1607 .................................... 48-103

Federal Executive Agency Guidelines on Employee

Selection Procedures, 41 Fed. Reg. 51734

(1976) ............................................. 48-103

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 23 ............ 1

x

PAGE

Legislative History

H.R. Rep. No. 92-238, 92nd Cong.

1st Sess. (1971) .................................... 108,109

H.R. Rep. No. 94-1558, 94th Cong. 2nd Sess. (1976) .... 120

S. Rep. No. 92-415, 92nd Cong. 1st Sess. (1971) ........ 108,109

S. Rep. No. 94-1011, 94th Cong. 2nd Sess. (1976) ...... 118,119

118 Cong. Rec. 790 (1972) ................................ 108

Other Authorities

American Psychological Association, Standards for

Educational and Psychological Tests (1974) ......... 48-103

APA Division of Industrial-Organizational Psychology,

Principles for the Validation and Use of

Personnel Selection Procedures (1975) ............. 49-103

Barrett, Content or Construct Validity: What's the

Difference? (1976) .................................. 53,62

Cooper and Sobol, Seniority and Testing Under Fair

Employment Laws: A General Approach

to Objective Criteria of Hiring and Promotion,

82 Harv. L. Rev. 1598 ( 1969) ....................... 25

Edwards, Order and Civil Liberties: A Complex Role

for the Police, 64 Mich. L. Rev. 47 (165) ......... 110

Edwards, The Police on the ’Urban Frontier

(New York 1968) ..................................... 113

Gastwirth and Haber, Defining the Labor Market for

Egual Employment Standards, 99 Monthly

Labor Review 32 (March 1976 )................ ....... 107

Kerner Commission, Report of the National Advisory

Commission on Civil Disorders, (Bantam edition:

1968) ................................................. 110,111,

113

An Overview of the 1978 Uniform Guidelines on

Employee Selection Procedures, 4 3

Fed. Reg. 38290 ..................................... 57

President's Commission on Law Enforcement and

Administration of Justice, Task Force Report:

The Police (GPO 1967)............................. 110,111,113

xi

PAGE

Legislative History

H.R. Rep. No. 92-238, 92nd Cong.

1st Sess. (1971) ................................... 108,109

H.R. Rep. No. 94-1558, 94th Cong. 2nd Sess. (1976) .... 120

S. Rep. No. 92-415, 92nd Cong. 1st Sess. (1971) ....... 108,109

S. Rep. No. 94-1011, 94th Cong. 2nd Sess. (1976) ...... 118,119

118 Cong. Rec. 790 (1972) .............................. 108

Other Authorities

American Psychological Association, Standards for

Educational and Psychological Tests (1974) ........ 48-103

APA Division of Industrial-Organizational Psychology,

Principles for the Validation and Use of

Personnel Selection Procedures (1975) ............. 49-103

Barrett, Content or Construct Validity: What's the

Difference? (1976) ................................. o3,62

Cooper and Sobol, Seniority and Testing Under Fair

Employment Laws: A General Approach

to Objective Criteria of Hiring and Promotion,

82 Harv. L. Rev. 1598 (1969) .... ................. 25

Edwards, Order and Civil Liberties: A Complex Role

for the Police, 64 Mich. L. Rev. 47 (165) ........ 110

Edwards, The Police on the 'Urban Frontier

(New York 1968) .................................... 113

Gastwirth and Haber, Defining the Labor Market for

Equal Employment Standards, 99 Monthly

Labor Review 32 (March 1976 )....................... 107

Kerner Commission, Report of the National Advisory

Commission on Civil Disorders, (Bantam edition:

1968) ............................................... 110,111,113

An Overview of the 1973 Uniform Guidelines on

Employee Selection Procedures, 43

Fed. Reg. 38290 .................................... 57

President's Commission on Law Enforcement and

Administration of Justice, Task Force Report:

The Police (GPO 1967)............................ 110,111,113

xi

TABLE OF ABBREVIATIONS

"Thornberry, Vol. Ill,

6/22/77 at- Witness, trial transcript volume

number, date and page of

testimony,

"Richmond Dep.,

5/11/77 at

"DX ____ at

"PX at

"Uniform Guidelines,§

"EEOC Guidelines,

29 C.F.R. §

Witness, deposition, date, and

page of testimony.

Defendants' exhibit number ____

and page number.

Plaintiffs' exhibit number ____

and page number.

Uniform Guidelines on Employee

Selection Procedures (1978),

43 Fed. Reg. 38290 (Aug. 25,

1978) ,

EEOC Guidelines on Employee

Selection Procedures, 29 C.F.R.

§ 1607.

"FEA Guidelines,§

"APA Standards, if at

I f Division 14

Principles,at If

"Test 165.1"

Federal Executive Agency Guidelines

on Employee Selection Procedures,

41 Fed. Reg. 51734 (1976).

American Psychological Association,

Standards for Educational and

Psychological Tests (1974).

APA Division of Industrial-Organi

zational Psychology, Principles

for the Validation and Use of

Personnel Selection Procedures

(1975).

Multijurisdictional Police Officer

Examination, Test No. 165.1.

X ll

of that organization, and Gary Hearn, both of whom are black

officers employed in the Louisville Division of Police; and

Ronald Jackson, James Steptoe, and Len Holt, three black

applicants for such positions. Plaintiffs allege that the

City of Louisville, the Louisville Civil Service Board, the

Director of Civil Service, the Chief of Police, and other

defendants have engaged and are engaging in discrimination

against black persons on the basis of race or color in recruit

ment, testing, selection, hiring, assignment, promotion, dis

cipline, and other employment practices. The Fraternal Order

of Police, Louisville Lodge No. 6, and its president have

intervened as defendants.

On June 27, 1975, this Court entered an order determining

that the action was maintainable as a class action under Rule

23, Fed. R. Civ. P. This order, as amended on April 22, 1977,

provides as follows:

IT IS ORDERED AND ADJUDGED that the

plaintiff Louisville Black Police Officers

Organization, Incorporated, and the plain

tiff Shelby Lanier, Jr., be and they are

hereby designated as representatives of a

class which is composed of all persons

who are black and who are now or have been

police officers employed by the City of

Louisville and who allege that the rules,

regulations and practices of the defendants

have discriminated against black police

officers on the basis of their race with

regards to assignment, promotion and dis

cipline of personnel.

IT IS FURTHER ORDERED AND ADJUDGED

that the plaintiffs Ronald Jackson, James

Steptoe, Len Holt, and Gary Hearn be and

they are hereby designated as representa

tives of a class which is composed of

2

black persons who have sought to obtain

employment with the Louisville Police

Department and who allegedly have been

denied such employment on the basis of

arbitrary, capricious and racially dis

criminatory practices on the part of

the defendants. Said class also consists

of all black applicants for positions

with the Louisville Police Department

who will in the future seek jobs with the

Police Department, and who may be denied

employment because of the allegedly

racially discriminatory and arbitrary

practices complained of in the complaint.

Pending before this Court, following approximately five

weeks of trial on the merits between March and September of

1977, are the issues concerning discrimination in recruitment,

entry-level testing, selection, and hiring. See Order entered

March 2, 1977. Also pending before the Court is the motion far

a preliminary injunction filed by plaintiffs in April 1977 with

respect to the defendants1 use of the Mulitjurisdictional

Police Officer Examination, Test 165.1. See Order entered

June 17, 1977. Plaintiffs submit this post-trial brief in

support of their motion for a preliminary injunction and in

support of their proposed findings of fact, conclusions of law,

and order and judgment.

SUMMARY OF THE ARGUMENT

Defendants have engaged in a conspicuous and longstanding

pattern of discrimination against blacks in recruitment, tasting,

selection, and hiring for jobs as police officers, in violation

of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42

U.S.C. §1981, and 42 U.S.C. §1983 and the Fourteenth Amendment.

Defendants have a long history of racial segregation and dis

crimination against blacks in their police employment practices.

Prior to the commencement of this action in 1974, defendants

intentionally discriminated against blacks and defendants engaged

in practices which were not job related and which had a dis

criminatory effect on blacks. After this lawsuit was filed,

defendants corrected some of their discriminatory practices but

persisted in others. (Section I).

Defendants violated Title VII and §1981 by using the Multi-

jurisdictional Police Officer Examination, Test No. 165.1, in a

manner which had an extreme adverse impact on black applicants

and did not validly measure their qualifications for the job.

Defendants did not demonstrate that Test 165.1 has either con

tent validity or criterion-related validity for use in selecting

Louisville police officers, and defendants accentuated the adverse

impact of the test by using it in an improper manner. Alternative

selection procedures with less adverse impact on blacks were and

are available to defendants. (Section II).

4

As a result of defendants 1 extensive and longstanding pattern

of discrimination against blacks, the Louisville police force is

not representative of the substantial black population in the

community it serves. This Court has the power and the duty to

require the defendants to hire qualified blacks as police officers

on an accelerated basis until the effects of the past discrimina

tion have been eliminated. (Section III).

Although this lawsuit has been before the Court for more

than four years, many questions remain to be decided. Once the

Court determines that defendants have engaged in unlawsul dis

crimination, plaintiffs should be granted an interim award of

attorneys' fees to prevent financial hardship during the con

tinuation of this lengthy and costly litigation. (Section IV).

5

ARGUMENT

I. DEFENDANTS HAVE ENGAGED IN A CONSPICUOUS

AND LONGSTANDING PATTERN OF DISCRIMINATION

AGAINST BLACKS IN RECRUITMENT, TESTING,

SELECTION, AND HIRING FOR JOBS AS POLICE

OFFICERS.

A. Standards of Proof

The Supreme Court has held that proof of a racially dis

criminatory intent or purpose is necessary to show a violation

of the Equal Protection Clause- Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S.

229 (1976); Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan

Housing Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 265 (1977). "This is

not to say that the necessary discriminatory racial purpose

must be express or appear on the face of the statute, or that

a law's disproportionate impact is irrelevant . . . . Neces

sarily, an invidious discriminatory purpose may often be

inferred from the totality of the relevant facts, including the

fact, if it is true, that the law bears more heavily on one

race than another." Washington v. Davis, supra at 241-42. it

need not be shown that racial discrimination was a dominant or

primary purpose for the challenged action; rather, "proof that

a discriminatory purpose has been a motivating factor in the

decision" is sufficient. Arlington Heights, supra at 265-66.

Determining whether invidious discriminatory purpose was a

motivating factor requires "a sensitive inquiry into such cir

cumstantial and direct evidence of intent as may be available,"

including such factors as the impact of the challenged practice

6

and its historical background. Id. 266-68. As Justice Stevens

has noted,

Frequently the most probative evidence of

intent will be objective evidence of what

actually happened rather than evidence describ

ing the subjective state of mind of the actor.

For normally the actor is presumed to have

intended the natural consequences of his deeds.

This is particularly true in the case of

governmental action which is frequently the

product of compromise, of collective decision

making, and of mixed motivation. Washington v.

Davis, supra at 253 (Stevens, J., concurring).

The Sixth Circuit has held that the showing of discrimina

tory intent or purpose required by Washington v. Davis and

Arlington Heights may be inferred "from a pattern of official

action or inaction which has the natural, probable and foresee

able result of increasing or perpetuating school segregation."

NAACP v. Lansina Board of Education, 559 F.2d 1042, 1047-48

(6th Cir. 1977). The circuits uniformly have adopted this

objective standard for ascertaining segregative intent. See

United States v. Texas Education Agency, 564 F.2d 162, 168 (5th

Cir. 1977), and cases cited therein. The Sixth Circuit has

recognized that the objective standard applies to employment

discrimination cases as well: "a pervasive pattern of dis

criminatory effects may support an inference of intentional

discrimination underlying the individual charge of discrimina

tory firing." McBride v. Delta Air Lines, Inc., 551 F.2d 113,

115 (6th Cir.), vacated and remanded on other grounds, 434 U.S.

916 (1977). Proper findings of unconstitutional discrimina

tory purpose have been made and upheld where statistical

7

evidence of a disproportionate impact has been coupled with

other objective evidence of discrimination in employment.

See Harkless v. Sweeny Independent School District, 554 F.2d

1353, 1356-58 (5th Cir.), cert. denied, 434 U.S. 966 (1977);

Baker v. Columbus Municipal Separate School District. 462 F.2d

1112, 1114 (5th Cir. 1972); Feeney v. Massachusetts, ____ F. Supp.

____, 17 F.E.P. Cases 659 (D. Mass. 1978) (three-judge court);

Shield Club v. City of Cleveland, 13 F.E.P. Cases 1373 and 1394

(N.D. Ohio 1976). Where the disproportion itself is sufficiently

dramatic, that fact alone "may for all practical purposes demon

strate unconstitutionality. . . . " Washington v. Davis, supra

at 242. See also, Sanomeister v. Woodard, 565 F.2d 460, 467

JJ(7th Cir. 1977).

This inquiry into intent and purpose may be relevant but

is not required to show a violation of Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et sea.

"Congress directed the thrust of [that] Act to the consequences

of employment practices, not simply the motivation." Griggs v.

Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 432 (1971) (emphasis in original);

Washington v. Davis, supra at 246-47. A prima facie violation

of Title VII may be established either by evidence of disparate

treatment or by evidence of disparate impact. Disparate treat

ment is shown where there is evidence, for example, that an

1 / The Washington v. Davis-Arlington Heights standard also

applies to claims under 42 U.S.C. § 1983 for deprivation of

the rights secured by the Equal Protection Clause. See, e.g.,

Harkless v. Sweeny Independent School District, supra.

8

employer treats blacks less favorably than whites- In such

cases, as in cases under the Fourteenth Amendment, proof of

discriminatory motive is critical, but motive can be inferred

from the fact of differences in treatment. International

Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 335

n.15 (1977). And, as in cases under the Fourteenth Amendment,

gross statistical disparities alone may justify the inference

of a discriminatory motive and thus establish a prima facie

disparate treatment violation. Hazelwood School District v.

United States, 433 U.S. 299, 307-308 (1977); Teamsters, supra

at 339.

Title VII claims of disparate impact, cn the other hand,

need not be supported by any proof of discriminatory motive.

Teamsters, supra at 335-36 n.15; Griggs, supra at 432. See

also, United States v. City of Chicago, 573 F.2d 416, 420-23

(7th Cir. 1978). To establish a prima facie disparate impact

case, a plaintiff need only show, for example, that a facially

neutral test or other selection practice selects applicants for

hire or promotion in a significantly disproportionate pattern.

Once this is shown, the burden shifts to the employer to prove

that the practice is job related. If the employer meets this

burden, the plaintiff may then show that other selection devices

without a similar discriminatory effect would also serve the

employer's legitimate interests. Dothard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S.

321, 329 (1977); Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 425

(1975).

Although the Supreme Court has recognized that Title VII

9

and 42 u.S.C. § 1981 embrace "parallel or overlapping remedies

against discrimination," Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415

U.S. 36, 47 and n.4 (1974), that Court has not yet expressly

decided whether the standards of proof are the same under both

statutes. In this circuit, however, the law is that Title VII

principles as to the order and allocation of proof "apply with

equal force to a § 1981 action," Long v. Ford Motor Co., 496

F.2d 500, 505 n.ll (6th Cir. 1974), and that a prima facie viola

tion of § 1981 may be established by proof of either disparate

treatment or disparate impact. Id. at 506. Other circuits

have concluded subsequent to the Supreme Court's decision in

Washington v. Davis, supra, that the standards of proof under

§ 1981 remain identical to those under Title VII. See Johnson

v. Ryder Truck Lines, Inc., 575 F.2d 471, 474 (4th Cir. 1978);

Davis v. County of Los Angeles, 566 F.2d 1334, 1338-40 (9th

Cir. 1977), cert, granted, 46 U.S.L.W. 3780 (June 19, 1978).

Cf. Kinsey v. First National Securities. Inc.. 557 F.2d 830

2/838 n.22 (D.C. Cir. 1977).

v

2/ The Sixth Circuit, citing Washington v. Davis, supra, 426 U.S.

at 247-48, has also noted that "[tjhe more rigorous 'discrimina

tory effect' test is still applicable to causes of action based

on statutory rights rather than on constitutional grounds, for

example, those granted under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964." NAACP v. Lansing Board of Education, supra, 559 F.2d

at 1046 n .3.

10

B. Prior to the Commencement of This Action in

1974, Defendants Engaged in a Clear Pattern

of Discrimination Against Blacks, and Defen

dants also Engaged in Practices Which Were

Not Job Related and Which Had a Discriminatory Effect on Blacks.

1. Statistical Evidence

From 1940 to 1950, the population of the City of Louisville

was approximately 15% black (see plaintiffs’ proposed finding 4),

but only 4-6% of the officers on the police force were black.

See plaintiffs' proposed finding 6. This stark disparity became

worse through the ensuing years and persisted even after this

action was filed in March 1974 (see plaintiffs' proposed findings

4-6) :

Black % of Black % ofLouisville LouisvillePopulation Year Police Officers

1960: 17.9% 1964 6.1%

1965 6.3%

1966 6.4%

1967 6.3%

1968 6.6%

1969 6.3%

1970: 23.8% 1970 6.3%

1971 6.1%1972 5.6%1973 5.6%1974 5.6%1975 7.0%

1977 7.4%

These statistics show the kind of imbalance which

is often a telltale sign of purposeful

discrimination; absent explanation, it

is ordinarily to be expected that non-

discriminatory hiring practices will in

time result in a work force more or less

representative of the racial and ethnic

composition of the population in the com

munity from which employees are hired.

11

Evidence of longlasting and gross dis

parity between the composition of a w r k

force and that of the general population

thus may be significant. . . . Teamsters .

supra, 431 U.S. at 340 n.20.

The extreme and longstanding disparities demonstrated in

this record are sufficient, standing alone, to establish a prima

facie case of racially motivated disparate treatment. Teamsters,

supra, 431 U.S. at 339; Hazelwood, supra, 433 U.S. at 307-308.

See also, Morrow v, Crisler, 479 F^2d 960, 961-62 (5th Cir. 1973),

modified on rehearing en banc on other grounds, 491 F.2d 1053

(5th Cir. 1974). This is the sort of "seriously disproportionate

exclusion of Negroes . . . [which] may for all practical purposes

demonstrate unconstitutionality because- . . . the discrimination

is very difficult to explain on nonracial grounds." Washington v .

Davis, supra, 426 U.S. at 242. Former Director of Safety James

Thornberry explained that it was in fact based on racial grounds :

"there was a good deal of prejudice in the Police Department

against the use of black police at that time [the 1950s]."

Thornberry, Vol. Ill, 6/22/77 at 404.

The disparities shown here demonstrate that this prejudice

continued to dominate the defendants1 employment practices well

after the 1950s and at least until this lawsuit was filed in 1974.

See Afro American Patrolmens League v. Duck, 503 F.2d 294, 299

2 J(6th Cir. 1974); League of United Latin American Citizens v . 7

7 / The Sixth Circuit in Duck affirmed a finding of discrimination

in police hiring practices based in part on evidence that the

minority population of Toledo was 16% but the minority representa

tion in the Toledo police department was only half that figure,

8.2%. 503 F.2d at 299. The disparities in Lousiville have always

been substantially greater. See plaintiffs’ proposed findings 4-6.

12

City of Santa Ana, 410 F. Supp. 873, 896-98, and cases cited

therein. From 1964 through 1973, only 11 of 328 new officers

accepted into recruit school classes, or 3.4%, were black (see

plaintiffs' proposed finding 8; PX 7):

Number of Whites Number of Blacks

Graduation

Year

Accepted Into

Classes

Accepted

Classes

1964 25 2

1965 15 0

1966 38 2

1967 29 2

1968 16 0

1969 24 1

1970 24 0

1971 36 0

1972 28 2

1973 82 2

There is a significant disparity between the number of black

officers hired during this period and the number one would expect

to have been hired based on any reasonable standard of comparison.

The Supreme Court has recognized that comparisons between the per

centage of minorities in an employer's work force and the percentage

of minorities in the general population of either the city or the

surrounding metropolitan area may be highly probative evidence of

intentional discriminaton where the job skill involved is "one that

many persons possess or can fairly readily acquire." Hazelwood,

supra, 433 U.S. at 308 n.13; Teamsters, supra, 431 U.S. at 337

n.17. Such comparisons may have less probative value when special

13

qualifications are required to fill particular jobs. Hazelwood.

supra at 308 n.13. The police officer's job, like the truck

driver's job in Teamsters and unlike the public school teacher's

job in Hazelwood, does not require an applicant to possess

advanced degrees or other specialized training or experience prior

to employment; instead, new police officers are given extensive

training after they have been hired. See Nevin, Vol. iv,, 6/5 3/77

at 506-510, 523-54. Accordingly, as in Teamsters. comparisons be

tween the percentage of blacks hired as Louisville police officers

and the racial composition of the general population are highly

probative. See also. League of United Latin American Citizens v .

City of Santa Ana, supra, 410 F. Supp. at 891.

Whether the geographic area for comparison is defined by the

Louisville city limits or by the far broader boundaries of the

_4/Louisville Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area (SMSA), the

evidence of purposeful discrimination is clear. In 1970, blacks

accounted for 12.2% of the population of the SMSA and 23.8% of the

population of the City of Louisville. But from 1964 through 1973,

only 3.4% of the officers accepted into recruit school were black.

This stark disparity between the proportion of blacks hired and

the proportion one ordinarily would expect to have been hired from

either the City or the SMSA is "a telltale sign of purposeful dis

crimination." Teamsters, supra, 431 U.S. at 340 n.20. 4

4_/ Plaintiffs submit that the proper geographic area to use in

determining the existence of a prima facie case, as well as in

setting an appropriate percentage goal for affirmative hiring relief

(see Section III, infra), is the City of Louisville. The courts,

including the .Sixth Circuit, "have consistently looked to the city,

i.e., the geographic area served by police and fire departments, in

considering the existence of a prima facie case." League of United

Latin American Citizens v. City of Santa Ana, supra, 410 F.Supp. at

14

Even if, as claimed by defendant's expert Dr. Michael Spar, the

appropriate population for comparison included all persons in the

1970 civilian labor force throughout the SMSA who were between the

ages of 20 and 34 and who were high school graduates or above in

educational level (see DX 28; Spar, Vol. Ill, 6/22/77 at 354-

55), the disparities would remain highly significant. The black

proportion of the group defined by Dr. Spar was 10%. Id_. Thus,

10% or 33, of the 328 officers accepted into recruit classes from

1964 through 1973 would be expected to be black if officers were

hired on a nondiscriminatory basis. Cf. Teamsters, supra, 431,

U.S. at 340, n.20. However, only 11 blacks were actually hired

4/ Cont'd.

896 and cases cited therein. See also, Afro American Patrolmens

League v. Duck, supra, 503 F.2d at 299; Davis v. County of Los

Angeles, supra, 566 F.2d at 1337; Pennsylvania v. Flaherty, 404

F.Supp. 1022' (W.D. Pa. 1975); Officers for Justice v. Civil Service

Commission, 371 F.Supp. 1328, 1330-31 (N.D. Cal. 1973). Cf.

Stamps v. Detroit Edison Co., 365 F.Supp. 87, 111 (E.D. Mich. 1973),

aff'd in part and rev'd on other grounds, sub nom. EEOC v. Detroit

Edison Co.. 515 F.2d 301 (6th Cir. 1975), vacated and remanded on

other grounds, 431 U.S. 951 (1977); Crockett v. Green, 534 F.2d

715, 718 (7th Cir. 1976). The defendants in this case have argued

that the Court should ignore the substantial weight of precedential

authority and look instead to the entire SMSA. However, the

evidence shows that police officers are required to live within 20

miles of police headquarters at 7th and Jefferson Streets in

Louisville (see PX 63-69); that they are required to secure Kentucky

operator's licenses (see PX 63-69) and thus, in effect, to be

residents of the State of Kentucky (see KRS 186.412-186.414;

Mitchell, Vol. Ill, 9/28/77 at 503, 507); and that in recent years

42-51% of the candidates on eligible lists have been residents of the

City of Louisville and another 31-40% have been residents of other

parts of Jefferson County. (Lee, Vol. IV, 7/14/77 at 634-36)-.

On these facts, the ’Louisville SMSA — which includes Clark and

Floyd Counties in Indiana, and Bullitt and Oldham Counties as well

as Jefferson County in Kentucky (see Vahaly, Vol. Ill, 6/22/77 at

313-15)— clearly is far too wide an area to be a proper basis for

comparison.

15

during this period. PX 7. The statistical analysis adopted by

the Supreme Court in Castaneda v. Partida, 430 U.S. 482, 496-97

n.17 (1977), shows that there is a difference of more than 4

standard deviations between the expected number and the actual

mumber of blacks hired based on Dr. Spar's view of the relevant

5/labor market. Because "a fluctuation of more than two or three

standard deviations would undercut the hypothesis that decisions

were being made randomly with respect to race," Hazelwood, supra,

433 U.S. at 311 n.17, this statistical comparison indicates the

existence of intentional discrimination against blacks in hiring

during the period in question. _Id. at 308-09 and n.14.

Moreover, if the comparison population is more appropriately

defined as the 1970 population of the City of Louisville, the dis

parity is even more pronounced. Since the black proportion of

this group was 23.8%, see PX 111, nondiscriminatory hiring practices

should have resulted in the hiring of 78, not 11, black officers

from 1964 through 1973. The Castaneda analysis shows that there

is a difference of more than 8 standard' deviations between the

actual and the expected numbers of blacks hired during this period

£/based on the City of Louisville data. Thus, under either view of

5/ The Castaneda statistical model measures fluctuations from the

expected value in terms of the standard deviation, which is defined

as the square root of the product of the total number in the sample

(here, 328) times the probability of selecting a black (33/328 = 0.1006)

times the probability of selecting a white (295/328 = 0.8994). Thus,

the standard deviation based on Dr. Spar's view of the relevant labor

market is 5.45. The difference between the expected and observed

numbers of blacks hiring during this period is 4.04 standard

deviations ([33-11/5.45 - 4.04). 430 U.S. at 496-97 n.17.

6/ The standard deviation is the square root of the product cf the

total number in the sample (328) times the probability of selecting

a black (78/328 - 0.2378) times the probability of selecting a white

(250/328 - 0.7622). Thus, the standard deviation is 7.71. There is

a difference of 8.69 standard deviations between the expected and

observed numbers of blacks hired ([78-11]/7.71 = 8.69). 430

U.S. at 496-97 n.17.

16

the relevant comparison population, the disparity exceeds that

which the Supreme Court found indicative of intentional discrimina-

2/txon in Hazelwood, supra. 433 U.S. at 308-09 and n.14, 311 n.17.

The resulting inference of discrimination in hiring is further

supported by applicant flow data, which provide "very relevant"

additional proof of intentional discrimination. Id. at 308 n.13.

8/Here, the only available applicant flow data for this period show

that 20% of the 413 persons who applied between July and December

1973 were black (PX 71, Books 6-7), but only 2 of the 84 officers

appointed in 1973 were black (PX 7). See plaintiffs' proposed

finding 23. This is far removed from the pattern one would expect

to result from nondiscriminatory hiring practices. Cf. Teamsters.

supra, 431 U.S. at 340 n.20.

7/ The result is the same if the relevant labor market is defined

as all 1970 residents of the City of Louisville who were 25 years

of age or older and were high school graduates with no further

education or who were between the ages of 18 and 24 and (1) had

completed four years of high school and were not enrolled in school

or (2) were enrolled in their fourth year of high school. Since the

black proportion of this population was 20.4%, see PX 111, nondis

criminatory hiring practices should have resulted in the hiring of

70 black officers instead of 11 from 1964 through 1973. There is

a difference of almost 8 standard deviations between these figures.

See Castaneda, supra. 430 U.S. at 497-97 n.17.

8/ Defendants did not keep records of the race of applicants

prior to July 1973. See PX 71, Books 1-6.

17

2. Recruitment and Selection Practices

This extreme departure from the expected hiring pattern

was a direct result of both intentional discrimination in re

cruitment and hiring and the use of discriminatory tests and

other discriminatory selection practices. It is clear from

the record that, at least until this action was filed in 1974,

there was a strict upper-limit quota on the number and percentage

of black officers allowed to be on the force at any one time.

See plaintiffs' proposed findings 6-8. From 1964 through 1973,

black officers never accounted for more than 6.6% of the police

force (PX 38), and between 15 and 82 new white officers but

never more than 2 new black officers were accepted into the

recruit school classes which graduated in each of those years

(PX 7) .

These restrictions were accomplished in part by the defen

dants' negative reputation in the black community for discrimina

tion against black applicants and black police officers. See

plaintiffs' proposed findings 20-21. This reputation deterred

many blacks from seeking jobs on the force. Id. The defendants

and their predecessors were aware that in the black community

there was "considerable peer pressure against young men . . .

becoming policemen." Burke, Vol. Ill, 6/22/77 at 384; Burton,

Vol. Ill, 6/22/77 at 397-98. The defendants also claimed that

between 1965 and 1972 there were always vacancies in the Division

-18-

of Police and there was a continual shortage of applicants to

fill those vacancies. Richmond Dep., 5/11/77 at 87, 98-99.

But after a short-term effort by James Thornberry in the early

1950s which was allowed to succeed only in a very limited way,

see Thornberry, Vol. Ill, 6/22/77 at 404-406, defendants took

no active role in attempting to recruit black applicants until

after the filing of this lawsuit. See plaintiffs' proposed

finding 22. This failure or refusal to recruit black applicants

for jobs as police officers constituted "a pattern of official .

inaction which [had] the natural, probable and foreseeable

result" of perpetuating the exclusion of blacks from the police

force. NAACP v. Lansing Board of Education, suora, 559 F.2d

at 1047-48.

When blacks overcame these obstacles and attempted to apply

for jobs as police officers, they were met with other discrimina

tory barriers to employment. The selection procedures which

defendants used prior to the commencement of this action in 1974

are set forth in plaintiffs' proposed finding 24. Whien the

defendant Civil Service Board reviewed these procedures in

January 1975, it made the following findings: the receptionist

in the Civil Service office was making all decisions as to the

right of an applicant to fill out an application, without ever

conducting an initial interview to determine whether the appli

cant met the minimum qualifications with respect to such

-19 ~

characteristics as "speech defect, " "marked deformity, " vision,

education, age, and military discharge and Selective Service

status; agency requisitions were not being processed in accordance

with Civil Service rules and regulations; applicants who were

certified by Civil Service for employment were sometimes dis

qualified by the agencies without any written reasons; proper

eligibility lists were not maintained; a backlog of vacancies

had developed, and open-continuous testing had to be used for

several months to eliminate the backlog; proper job analysis

procedures were not followed; the written test was not validated

and was deficient in many respects; the oral interviews for

police officer were unstructured and subjective, and they were

not validated; test weights were set in an arbitrary manner;

the physical fitness standards were not valid and they did not

necessarily measure physical stamina or physiological ability

to tolerate stress; the Division of Police conducted the back

ground investigation and made recommendations to disqualify

applicants which usually were accepted by the Civil Service

Director without information as to whether the reason for dis

qualification was job-related; and the practice of giving a

"training and experience" rating gave an extra advantage to

persons with "inappropriate" training and experience which was

not required to do the job and also benefited applicants who

received high scores on the unvalidated written test. See

plaintiffs' proposed finding 25.

-20-

The disproportionate exclusion of blacks from the force

on these grounds bearing no demonstrable relationship to job

performance violated Title VII and 42 U.S.C. §1981- See, e.g.,

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., supra, 401 U.S. at 432; Albemarle

Paper Co. v. Moody, supra, 422 U.S. at 425; Davis v. Countv

of. Los Angeles, supra, 566 F.2d at 1340-42; Johnson v. Ryder

Truck Lines, Inc., supra, 575 F.2d at 474; Dozier v. Chupka,

395 F.Supp. 836, 850-52 (S.D. Ohio 1975). Moreover, defendants

disqualified applicants on the basis of several specific

criteria which have been shown to have an adverse impact on

blacks and which were not job-related, such as (1) juvenile and adult

arrest records, PX 63-67, 79, 85; Richmond Dep., 5/23/77 at 312 —

see United States v. City of Chicago, 549 F.2d 415, 432 (7th Cir.^

cert. denied. 434 U.S. 875 (1977); Gregory v. Litton Systems, Inc.,

472 F.2d 631 (9th Cir. 1972); (2) maximum weight standards, PX

63-67 — see VonderHaar, Vol. Ill, 9/28/77 at 431; and (3) financial

condition, Richmond Dep., 5/11/77 at 76 — see United’ States

v. City of Chicago, supra, 549 F.2d at 432; Wallace v.

Debron Corp., 494 F.2d 674 (8th Cir. 1974); Johnson v. Pike

Corp., 332 F.Supp. 490 (D.D. Cal. 1971).

The written tests which defendants used during this period

also had an adverse' impact on blacks and were not job-related.

"Test for Policeman (10-D)," Px 19-20, was used until 1971

despite the fact that there had been serious doubts about its

security since at least 1965. Richmond Dep., 5/11/77 at 19,

5/23/77 at 98-99; Olges, Vol. II, 7/12/77 at 190-91. The defendant

- 2 1 -

Civil Service Board found that parts of this test were not job-

related or did not apply to the job of a Louisville police officer.

Id; Richmond Dep., 5/23/77 at 149. See plaintiffs' proposed

finding 26. Similarly, "Examination for Police Patrolman No.

0044, " PX 18, which was used from 1971 to 1975, was "out of gear"

according to former Director of Safety James Thornberry, Vol. Ill,

6/22/77 at 411; "they were vocabulary-type tests, I.Q. tests,

AGC-type things, .. . which are not particularly job-related." Id_. at

413. See plaintiffs proposed finding 27.

When Darryl Olges became Chief Examiner in May 1975, he

performed a study of tests and other civil service selection

procedures which confirmed Thornberry's view. Olges, Vol. II,

7/12/77 at 132-85; 190-99. The defendant Civil Service Board

found in 1975 that many of its written tests were outdated and

no longer applicable to the job duties in question; that item

analyses had not been performed; that "[a]11 questions were

related to a candidate's knowledge, rather than his skill or

ability in performance, and a definite advantage was extended

to those who had the benefit of advanced education"; that "[a]11

written examination procedures were posited on the applicant's

ability to reduce his skill or his performance to a mental

exercise and be able to relate that with paper and pencil";

that the persons grading examinations had knowledge of the names

and personal information concerning candidates, and that test

- 22 -

security — which was "of utmost importance for fairness and

non-discriminatory practices" — continued to be a serious

problem; that examination grade scales were in many instances

outdated and not adjusted for current relevance; that in most

instances heavy weight was given to written tests based on

academic materials; and that test weights were set in an

arbitrary manner. DX 75, "Narrative" at 8, 12, 14. The Board

further found that Police Patrolman Examination No. 0044 had

been scored and used as a ranking device with a weight of 65%

of the total examination process without any available rationale

for the cut-off score of 52, and that "[t]he written examination

as it stood prior to August 1st [, 1975] was not validated." DX 75,

"Louisville Civil Service Board Selection Procedures and Recruit

ment Program, Book I" — "Written Entrance Test" at 1-2. The

written test also had been administered in a manner which per

mitted candidates to memorize the items; an item analysis was

finally performed and it showed that many of the items did not

adequately differentiate between candidates; parts of the written

test were not sufficiently related to the content of the police

officer's job; and the test placed too much emphasis on reading

and mathematics skills and was "approximately 80-90% invalid."

Olges, Vol. II, 7/12/77 at 182-85, 188-99; Vol. I, 7/11/77 at 155; DX 38

The available evidence demonstrates that these written tests

had a substantial adverse impact on blacks. For example, in 1975

-23-

only 12 of 342 white applicants (3.5%) failed Examination No.

0044, PX 18, but 14 of the 93 black applicants (15.1%) failed

this test. DX 75, "Statistical Data, Book Three" — "General

Statistical Summary, Sworn Personnel, " at f6. Because

defendants did not keep records of the race of applicants prior

2/to July 1973, and because the records which were kept between

July 1973 and December 1975 are unreliable and in many instances

10/

illegible, the record does not permit a precise mathematical

computation of the adverse impact which these written tests

had on black applicants prior to the institution of this action.

However, the record shows that tests of this kind traditionally

have an adverse impact on minorities, Barrett, Vol. IV, 7/14/77

at 556, and it has long been widely recognized that black and

other minority persons typically perform below the norm for

whites on such culturally biased paper-and-pencil tests of

generalized intelligence or aptitude. Boston Chapter, NAACP,

Inc, v. Beecher, 504 F.2d 1017, 1021 (1st Cir. 1974), cert.

denied, 421 U.S. 910 (1975); Bridgeport Guardians, Inc, v.

Members of Bridgeport Civil Service Commission, 482 F.2d 1333, 1340

(2d Cir. 1973) cert, denied, 421 U.S. 991 (1975); League of United

9/ See PX 71, Books 1-6.

10/ See DX 75, "Statistical Data, Book Three" — "Statistical

Variables" at 1-2. See also, Affidavit of Joshua Tankel, filed

herewith.

-24-

Latin American Citizens v. City of Santa Ana, supra, 410 F.Supp.

at 902. See Cooper & Sobol, Seniority and Testing Under Fair

Employment Laws; A General Approach to Objective Criteria of

Hiring and Promotion, 82 Harv. L. Rev. 1598, 1640 (1969).

In view of the gross underrepresentation of blacks on the Louis

ville police force and in view of the defendants' failure to keep

adequate records concerning the impact of its tests, it can properly

be inferred that these tests had an adverse impact on black

applicants. See §4d , Uniform Guidelines on Employee Selection

Procedures (1978), 43 Fed. Reg. 38290 (Aug. 25, 1978).

The Civil Service Board's review of its pre-1975 selection

procedures disclosed not only that many of its practices and

criteria were not demonstrably related to successful job per

formance, but also that many applicants and potential applicants

were being rejected on the basis of arbitrary, subjective

determinations and improper procedures on the part of defendants

and their employees and agents. See plaintiffs' proposed finding

25. As the Supreme Court has held in the context of jury selec

tion, "a selection procedure that is susceptible of abuse or

is not racially neutral supports the presumption of [intentional]

discrimination raised by the statistical showing. Washington v .

Davis, 426 U.S., at 241. . ..." Casteneda v. Partida, supra,

430 U.S. at 494. The same principle has been applied in employ

ment discrimination cases. See, e.g., Stewart v. General Motors

-25-

Corp., 542 F .2d 445, 450 (7th Cir. 1976), cert. denied, 443

U.S. 919 (1977); Rowe v. General Motors, 457 F.2d 348, 358-59

(5th Cir. 1972).

The testimony of a number of individual witnesses in this

case demonstrated that this potential for abuse was realized

when blacks sought to become police officers. For example,

when Norma Boyd tried to apply for the job over a period of years,

white receptionists in the Civil Service office repeatedly re

fused to give her an application form for a variety of spurious

reasons: first, in 1971, she was told that a GED certificate was

inadequate, Boyd, Vol. I, 4/25/77 at 39; second, in 1972, she

was told that a year of college was required of all applicants,

id. at 43; and third, in 1973, she was told that she was too

short, id. at 44. In fact, in 1971 and 1972 a GED certificate

was acceptable (PX 21E; Richmond Dep., 5/23/77 at 139), and a

year of college was not required (PX 21c). And the defendant

Civil Service Board had specifically directed in September

1972— six months before Boyd was denied an application on theii/ground that she was too short — that persons who did not appear

to meet the height qualifications must nevertheless be given an

application. PX 70. Finally in 1974, three years after her

11/ Officer James Brown reported a similar experience. In 1972

or 1973, after he had been on the police force for two to three

years, Brown decided to go to the Civil Service office in

civilian clothes and ask for an application, "[t]o see where

in the whole scale of things were blacks being cut loose, where

-26-

initial attempt, Boyd was given an application form by a black

receptionist. Boyd, Vol. I, 4/25/77 at 48.

In addition, black applicants were subjected to unexplained

delays in the processing of their applications, and they were

disqualified on the basis of inaccurate information which the

defendants refused to correct. David Lyons first applied

in 1969. He filled out an application and passed the written

test, the records check,the physical fitness test, and the medical

examination. Lyons, Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at 657-59. Although most

applicants were then certified immediately to the Division of

Police and were hired shortly thereafter (Lee, Vol. II, 6/21/77

at 260-61; Richmond Dep., 5/11/77 at 43-44, 84-85), it was not

until April 1970, four to five months after he had applied, that

Lyons received a letter from the Civil Service Board informing

him that he had been disqualified by the character or background

investigation due to his military record. Lyons, Vol. IV,

4/28/77 at 659, 670. When Lyons went to the Civil Service office

to question his disqualification, he learned that it was based

on speculation by Civil Service as to why he had been granted an

honorable discharge for the "convenience of the government."

1V Cont'd

they were being shoved out." Brown, Vol. IV, 4/28/77 at

580-82. When he asked for the application, the woman at the

desk refused to give it to him on the ground that he was too

short to qualify for the job of police officer. Id. at 582-83.

Brown is six feet tall. Id. at 582.

-27-

Id. at 660-61. No one in the Civil Service office made any

attempt to determine the reason for this discharge from any

official source. Instead, even after Lyons himself had secured

the reason and advised the defendants of the basis for the dis-J2/

charge, they refused to accept his explanation and correct the

erroneous disqualification. I<2. at 661. Only after Lyons spoke

to Senator Cook and the Senator intervened on his behalf was

Lyons allowed to become a police officer. Id_. at 662-63.

Ronald Jackson, another black applicant and a named plain

tiff in this action, was also initially disqualified on the

basis of inaccurate Civil Service Board information. He first

applied to be a police officer in 1973, with three years of

college work in law enforcement and one year of experience in

the Army Military Police. Jackson, Vol. II, 4/26/77 at 255,

257. He passed the written test and then took the medical

examination. Id. at 25 8-59. About a week later, after not hearing

anything further regarding his application, Jackson inquired at

the Civil Service office and was told that he had failed the

eye examination. Id. at 260. Although defendants' files

variously indicated that Jackson's vision was 20/100 in each eye

12 / in fact, the discharge was granted for the"convenience

of the government" because, when Lyons returned from overseas

with only about 20 days left to serve, it was easier for the

Army to discharge him early than to reassign him to another

unit. Id. at 661.

-28-

(DX 15, Richmond letter dated Nov. 13, 1973) or 20/70 in each

eye (DX 15, Lawwill letter dated Dec. 7, 1973), Jackson has

never had any serious problems with his eyes and had never been

disqualified from any job because of his eyesight. Id_. at 261.

After consulting the Louisville Urban League, Jackson was re

examined by an opthamologist who determined that his uncorrected

visual acuity was 20/50-1 in each eye separately and 20/40-1

with both eyes together. DX 15, Schiller letter dated Sept. 24,

1974. Based on this examination, the Civil Service Board finally

decided in September 1974 that Jackson met the visual standards

and that he should be contacted to complete his processing for

entrance into the police department. DX 15, Richmond letter

dated Sept. 27, 1974. However, Jackson instead was given a

temporary job as a jail guard, and he had no further contact

from the defendants concerning his application for a job as a

police officer until he attended a meeting arranged by the

Urban League in the summer of 1975 to discuss the cases of a

number' of black applicants who had been screened out by the

selection process as he had been. Jackson, Vol. II, 4/26/77 at

268-70.

The way was apparently clear for Jackson to become a police

officer as of September 1974, but his processing was unaccountably

delayed until well after Jack Richmond had left as Civil Service

Director. It was not until July 15, 1975, almost ten months

later, that the new Director, Jeanette Priebe,apologized to

-29-

Jackson because he had been "put to so much inconvenience"

and informed him that he would be the first applicant referred

to the police department when it next started hiring. DX 15,

Priebe letter dated July 15, 1975. During this delay, many

other applicants were hired. See PX 53. Jackson was finally

admitted to recruit school in November 1975, almost two years

after he had first applied. Jackson, Vol. II, 4/26/77 at 273.

Gary Hearn, another named plaintiff in this action,also

was denied a job as a police officer for more than a year on

the basis of erroneous information which the defendants re

peatedly refused to correct. Hearn was allowed to become a

police officer only after he had undertaken extensive efforts,

which included the securing of a court order, to force the

defendants to disregard their inaccurate information. See

plaintiffs' supplemental post-trial brief.

For a large part of the period in question, 1965 through

late 1974, Jack Richmond was the Director of Civil Service.

Richmond and the employees who worked under him had virtually

unlimited discretion over the operation of the entire civil

service selection and referral process. People who attempted

to apply for jobs were refused applications at the whim of the

receptionist; requisitions were not processed in accordance

with Civil Service rules and regulations; eligibility lists

were not maintained; proper job analysis procedures were not

followed; unvalidated written tests and other non-job related

-30-

criteria were used; subjective and unstructured oral interviews

were given. DX 75, "Narrative" at 2-14. See plaintiffs' pro

posed finding 25.

Throughout Richmond's tenure, applicants were not certified

or appointed in rank order from eligibility lists; instead,

whenever the Division of Police notified Richmond that it had

vacancies to fill, applicants were put through Richmond's pro

cedures, and those who survived were referred by Richmond for

appointment. Richmond Dep., 5/11/77 at 43-44, 84-85; Lee/

Vol. II, 6/21/77 at 260-61; Arnold, Vol. IV, 9/29/77 at 767,

778-82rcoleman, Vol. IV, 9/29/77 at 658; DX 75, "Narrative" at 4.

Richmond "had a lot to do with who was on that Police Department.

He was involved in the initial process all the way to the end."

Coleman, Vol. IV, 9/29/77 at 629-30. Richmond had the sole

authority until 1972, and substantial authority thereafter until

his departure in 1974> to determine who passed and who failed

the subjective and unstructured oral interview examination for

police officer. Richmond Dep., 5/11/77 at 79, and 5/23/77 at

247-48; Olges, Vol.II, 7/12/77 at 183-84; Arnold, Vol. IV, 9/29/77

at 768; Coleman, Vol. IV, 9/29/77 at 630; DX 75, "Narrative"

at 8-9 and "Louisville Civil Service Board Selection Procedures

and Recruitment Program, Book I" — "Oral Interview" at 1.

This procedure made Richmond the final judge of such subjective

factors as a candidate's "appearance," "voice and speech,"

-31-

sincerity," and "judgment."mental alertness," "stability," "

Richmond Dep., 5/23/77 at 231-46. The result of this con

centration of power in Richmond's hands was candidly, if

somewhat gingerly, described by former Director of Safety

James Thornberry:

[W]e had some difficulty with the gentleman

that was at that time the head of Civil Service

[Richmond], and we had to go to a great deal of

trouble, particularly on getting people past the

physical examination; and there were certain

other things . . ., they always ran a police

check and that sort of thing . . . . [Richmond]

was an ex-Army man with some rather rigid ideas

about things; and I heard as many complaints from

would-be white applicants as black, but the re

sult was that a whole lot of people were being

hurt, and . . . whether it was intentional or not,

I certainly wouldn't say, but generally, it seemed

to come down the hardest on the black applicants.

So consequently we had to do a lot of fighting

and scratching to get some of them past that

business. Thornberry, Vol. Ill, 6/22/77 at

409-410.

See also, Coleman, Vol. IV, 9/29/77 at 634-35;Arnold, Vol. IV,

9/29/77 at 771.As the record demonstrates, prior to the filing of this

lawsuit in 1974, very few black applicants were able to fight

and scratch their way past "that business." The defendants

selected police officers largely on the basis of tests and

other criteria which had an adverse impact on blacks and were

not job-related, and on the basis of arbitrary and subjective

criteria and procedures which were not racially neutral, were

susceptible to abuse, and were in fact abused by defendants.

The result was a strict limitation on the number and percentage

of black officers on the Louisville police force.

-32-

3. History of Racial Discrimination

The intentionally discriminatory nature of the defendants1

pre-lawsuit recruitment and selection practices is brought into

sharp focus by the City's long history of racial segregation and

discrimination in police employment practices. When the City of

Louisville established a police force in the 1820s, controlling

the black population and keeping black slaves from escaping across

the Ohio River were among its primary functions. Keil, Vol. IV,

9/29/77 at 737-38. When a limited number of blacks finally were

allowed to become officers on the force, they were restricted

primarily to the task of policing the black community. See plain

tiffs' proposed findings 9-12. Until well into the 1960s, all

black uniformed patrol officers were assigned to walking beats

i!/within rigidly defined boundaries of the second district, and

later the fourth district, without regard to their desires,

qualifications, or length of service. See plaintiffs' proposed

findings 9-10. As former Director of Safety James Thornberry-

testified, there was "a good deal of prejudice in the police

department against the use of black police at that time [the 1950s]

They thought that the only place black police officers could be

assigned was in the Second District." Thornberry, Vol. Ill,

6/22/77 at 404-405.

Moreover, black uniformed patrol officers were not permitted

to ride in patrol cars until 1964; blacks were .excluded from

_ / Black officers, were restricted to the area bounded by

6th Street on the east, 14th Street on the west, Jefferson Street

on the north and Esquire Alley or Broadway on the south. See

plaintiffs' proposed finding 9.

-33-

homicide, burgulary, and other special squads; blacks were re

quired to attend racially segregated daily meetings to receive

their orders; black recruits received inferior physical training

in racially segregated facilities; and black officers were not

given the same training opportunities as whites. See plaintiffs'

proposed findings 12, 14-15, 17-18.

Blacks were hired and promoted specifically to fill "black

jobs" in segregated units. See plaintiffs' proposed findings 7-8.

Until this lawsuit was filed in 1974, strict limits were maintained

on the number of black officers hired in any one year and on the

percentage of blacks on the force at any given time. See plain

tiffs’ proposed findings 6-8. Three positions specifically for

black sergeants were created in approximately 1944, and there