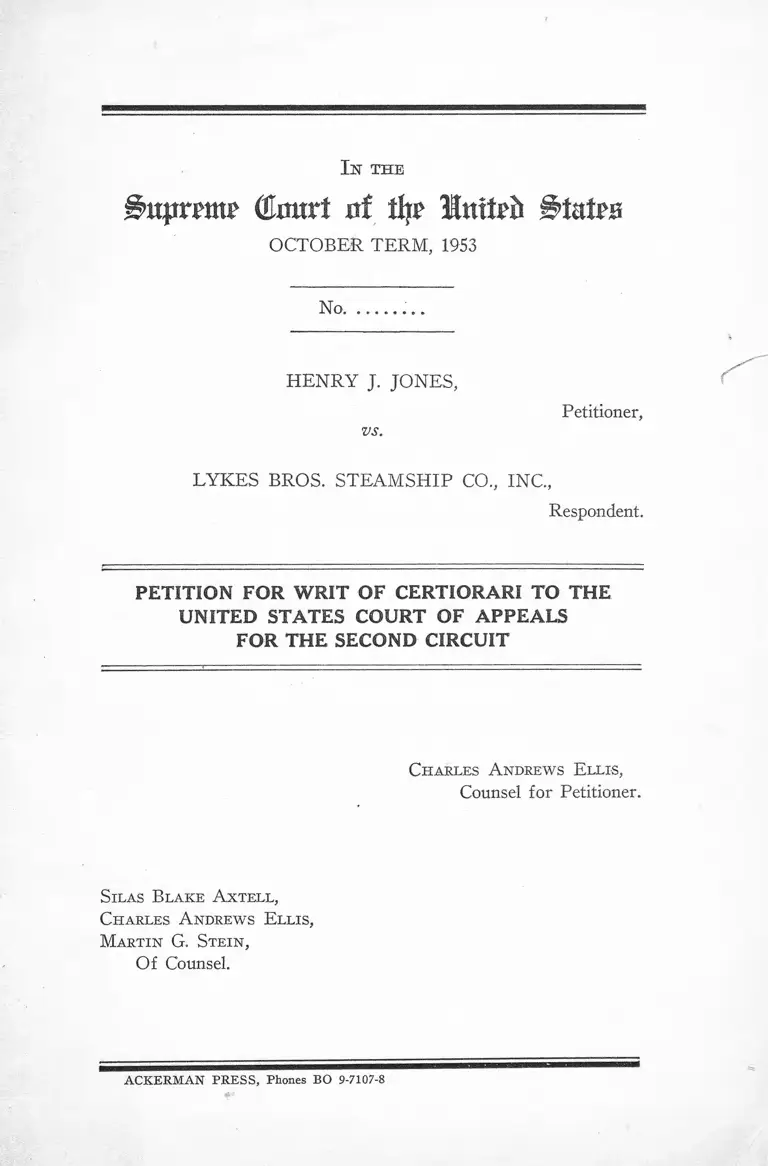

Jones v. Lykes Bros. Steamship Co., Inc. Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

July 31, 1953

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Jones v. Lykes Bros. Steamship Co., Inc. Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1953. e2926359-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/556e396d-0b3d-49bb-a727-dfbb4540c7ee/jones-v-lykes-bros-steamship-co-inc-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Copied!

I n the

CUmtrt at % Huttefr States

OCTOBER TERM, 1953

No.

HENRY J. JONES,

vs.

Petitioner,

LYKES BROS. STEAM SHIP CO., INC.,

Respondent.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

Charles Andrews Ellis,

Counsel for Petitioner.

Silas Blake Axtell,

Charles Andrews Ellis,

Martin G. Stein,

Of Counsel.

ACKERMAN PRESS, Phones BO 9-7107-8

INDEX

----------- PAGE

Opinions Below ........................... 1

Jurisdiction .............. 2

Questions Presented ..................................................... 2

Statutes Involved f . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . , . . , . . . ; . ....... 3

Statement ....................................................................... 4

Specifications of E r ro r s ................ .............................. 8

Reasons for Granting the Writ ...................... 9

I. The Court of Appeals’ erroneous treatment

of the assault in quarters as a risk assumed by

plaintiff, and its failure to give effect under mari

time law and Jones Act to the violation thereby

of defendant’s duty to provide and warranty of,

and Hunter’s consequent duty as an employee

.assigned to the same quarters as plaintiff to so

conduct himself as to secure to plaintiff, safe

quarters and opportunity for rest therein between

watches in safety from unprovoked assault by de

fendant or its employee assigned to the same

quarters.—Statutory violations, and conflicts and

confusion .of decisions............................................ 9

II. The violation of Fed, Rules of Civ, Proc.,

Rules 52, 75 and 76, and conflict with decisions

of this Court in reversing the determination of

unseaworthiness without the record containing the

evidence or defendant having designated or stated

such a point, or the Court of Appeals determining

or being in position to determine from the evi

dence that the District Court’s finding of unsea

worthiness was clearly erroneous,—Rules and de

cisions violated . . , ........................... . 19

IJL The erroneous ignoring of the theory of

plaintiff’s case and refusal to notice plaintiff’s

cross-appeal on the “ negligence” and inadequacy

.of damages questions.—Decisions in Conflict . . . . 21

Conclusion ..................................................................... 22

11 T able of A uthorities Cited

page

Cases:

Aguilar v. Standard Oil Co. of N. J. (1943), 318 U. S.

724 ........................................................................... 10

Alpha Steamship Corporation v. Cain (1930), 281 U. S.

642 .................................................................... 14,17,21

Anderson v. Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe By. Co.

(1948) , 333 U. S. 821 ........................................... 18

Baltimore & Ohio B. B. Co. v. Baugh (1893), 149 U. S.

368 ........................................................................... 18

Boudoin v. Lykes Bros. S. S. Co. (D. C. E. D. La.,

1953), 112 F. Supp. 177 ..................................11,12,17

Brown v. Pacific Coal Co. (1916), 241 U. S. 571, 573 .. 14

Buzynski v. Luekenbach Steamship Co. (1928), 277

U. S. 226 .................................. 21

Carlisle Packing Co. v. Sandanger (1922), 259 U. S.

255 ......................... 19,20,21

Carter v. Atlantic & Saint Andrews Bay By. Co.

(1949) , 338 U. S, 430, 431 ..................................16,18

Compagnie Generale Transatlantique v. Bivers

(C. C. A. 2d, 1914), 211 Fed. 294, certiorari denied,

232 U. S. 727 ......................................................... 12,14

Compton v. Hammond Lumber Co. (1936), 153 Or. 546 11

Cortes y. Baltimore Insular Line (1932), 287 U. S.

367 ..........................................................................10,11

Gleeson v. Virginia Midland B. B. Co. (1891), 140 U. S.

435 ........................................................................... 20

Jamison v. Encarnacion (1930), 281 U. S. 635 .. .14,15,17

Johnson v. United States (1947), 333 U. S. 46 .. .13,17,18,

19, 20, 21

Kable v. United States (D. C. S. D. N. Y. 1948), 77

F. Supp. 519 (C. A. 2d 1948), affd. 169 F. 2d 90 .. 17

Keen v. Overseas Tankship Corp. (C. A. 2d 1952), 194

F. 2d 515; certiorari denied 343 U. S. 966 ......... 15,17

Koehler v. Presque-Isle Transportation Co. (C. C. A.

2 Cir. 1944), 141 F. 2d 490 ............................. 15,16,17

Kyriakos v. Goulandris (C. C. A. 2d 1945), 151 F. 2d

132 .................................................................... 15,16,17

T able of A uthorities Cited iii

PAGE

Lillie v. Thompson (1947), 332 U. S. 459 .................... 12

Luekenbach et al. v. W. J. McCahan Sugar Refining Co.

and The Insular Line (1918), 248 U. S. 139......... 19

Mahnich v. Southern S. S. Co. (1944), 321 IT. S. 96 . .10,19

W. J. McCahan Sugar Refining Co. v, S. S. Wild-

croft (1906), 201 U. S. 378 ........................... 19

McCall y. Inter Harbor Navigation Co. (S. Ct. Or.

1936), 154 Or. 252 ................................................... 11

McDonough v. Buckeye S. S. Co. (D. C. N. D. Ohio,

1951), 103 F. Supp. 473; affd. (C. A. 6 Cir., 1953),

200 F. 2d 558; certiorari denied 345 U. S. 926. . 13,14,18

Nelson v. American-West African Line, Inc. (C. C. A.

2 Cir. 1936), 86 F. 2d 730; certiorari denied 300

U. S. 665 .......................................................... 15,16,17

Reck v. Pacific-Atlantic S. S. Co. (C. A. 2d, 1950), 180

F. 2d 866 ................. 13,14,18

Rooker v. The Alaska S. S. Co. (1936), 185 Wash. 71,

certiorari denied, 299 U. S. 552 ............................. 11

Searff v. Metcalf (1887), 107 N. Y. 211........................ 10

Steel v. State Line S. S. Co., L. R. 3 App. Cas. 72, 81,

82, 84, 86, 90, 91 ....................................................... 19

Sundberg v. Washington Fish and Oyster Co. (C. C. A.

9th, 1943), 138 F. 2d 801 ................................11,14,18

Terminal R. Assn, of St. Louis v. Stangel (C. C. A.

8th), 122 F. 2d 271; certiorari denied 314 U. S.

680 ........................................................................... 20

The Carib Prinee (1898), 170 U. S. 655 ...................... 19

The Lord Derby (C. C. A., E. D. La., 1883), 17 Fed. 265 11

Tiller v. Atlantic Coast Line R. Co. (1943), 318 U. S.

54 ..................................................... 12,13,17,18

United States v. Gypsum Co. (1948), 333 U. S. 364 . .20, 21

United States Shipping Board Emergency Fleet Cor

poration et al. y. Greenwald (C. C. A. 2d, 1927),

16 F. 2d 948 ............................................................ 11

IV S tatutes

PAGfi

Fed. Rtdes Civ. Proc.:

Rule 52, 28 U. S. C.............................................. 3,7,19,20

Rule 75, 28 U. S. C................... 3,5,19,20

Rule 76, 28 U. S. C..............................................3,5,19,20

United States Code:

Title 28, Sec. 1254(1)................................................... 2

Title 28, Sec. 2101(c) ................................................... 2

Title 45, Sec. 5 1 .................... ......................2,3,4,11,18

Title 45, Sec. 5 4 .................... ................ 2,3,4,11,12,18

Title 46, Sec. 391.................... ................................... 9

Title 46, Sec. 653 .................... ................................... 9

Title 46, Sec. 660a.................. ................................... 9

Title 46, Sec. 660-1 ................ ................................... 9

Title 46, Sec. 669 .................... ...................................9,10

Title 46, See. 673 .................... ................................... 10

Title 46, Sec. 688 .................... .................... 2,3,11,12,18

T extbook

Moore’s Federal Practice, 2nd Ed., Vol. 5, pages 2611-

2629 ......................................................................... 20

I n the

(Emirt 0! % Staten

October T erm, 1953

No,

----------♦----------

H enry J . J ones,

vs.

Petitioner,

Lykes Bros. Steamship Co., I nc.,

Respondent.

--------------------- *---------------------

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

To the H onorable, T he Chiee J ustice and the Associate

J ustices op the Supreme Court oe the U nited States:

Petitioner, an American seaman, prays for a writ of

certiorari to review the judgment of the United States

Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, entered June 4,

1953, which reversed a judgment for plaintiff for damages

for personal injuries and dismissed the complaint, and on

June 19,1953, denied plaintiff’s petition for rehearing filed

June 17, 1953.

Opinions Below

The opinion of the District Court (R. 10 to 17) is re

ported in 108 F. Supp. 323. The opinion of the Court of

Appeals (R. 25) is not yet published in Fed. 2d.

No opinion was rendered by the Court of Appeals in

denying petitioner’s application for rehearing.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals was entered on

June 4, 1953; thereafter petitioner filed a petition for re

hearing in said Court on June 17, 1953, which said Court

denied on June 19, 1953.

The jurisdiction of this Court is found in 28 U. S. Code,

Sees. 1254 (1) and 2101 (c).

Questions Presented

1. Where a seaman assigned to the same quarters on

shipboard as plaintiff committed unprovoked assault on

plaintiff on shipboard in the quarters and during the time

assigned to plaintiff for rest between watches:

(a) Whether unseaworthiness and unfitness of crew

and quarters is limited to the assaulting seaman’s known

or obvious unfitness broadly to serve as a member of a

ship’s crew, or covers particularly his unfitness and fail

ure, when assigned to the same quarters as plaintiff, and

defendant’s failure through him, to secure, allow and

maintain to plaintiff his right to safe quarters and oppor

tunity for rest between watches in safety from unpro

voked assault by such seaman, and supported, under the

findings, the District Court judgment for plaintiff herein.

(b) Whether under the Jones Act (46 U. S. C. See. 688),

and Federal Employers’ Liability Act (45 IT. S. C. Secs. 51

and 54) “ negligence” as covering assault is limited to

negligence of officers in employing a seaman of brutal or

dangerous reputation, or covers also both (i) the failure

of defendant to secure to plaintiff safe quarters and op

portunity for rest between watches in safety from unpro

voked assault by an employee of defendant assigned to the

same quarters, and (ii) the act of Hunter, an employee of

defendant assigned to the same quarters as plaintiff, in

3

committing unprovoked assault on plaintiff in the quarters

and during the time assigned to plaintiff for rest between

watches.

2. Whether the District Court’s determination of unsea

worthiness was a finding of fact which under Rules 52, 75

and 76 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, the Court

of Appeals lacked authority to review or set aside or re

verse, where defendant did not designate and the record

did not contain and the Court of Appeals did not review

the evidence or testimony or a condensed statement in

narrative form of all or part thereof, nor determine there

from that the District Court’s finding of unseaworthi

ness was clearly erroneous, and where defendant did not

serve with its designation any statement of such a point,

and

3. Whether the Court of Appeals erred in refusing to

notice plaintiff’s cross-appeal as to negligence and inade

quacy of damages and in reversing plaintiff’s judgment

and dismissing the complaint without consideration of

plaintiff’s cross-appeal.

Statutes Involved

The statutes involved are the Jones Act (46 U. S. C. Sec.

688) and Federal Employers’ Liability Act (45 U. S. C.

Secs. 51 and 54).

46 U. S. C. Sec. 688 provides:

“ Any seaman who shall suffer personal injury in the

course of his employment may, at his election, maintain

an action for damages at law, with the right of trial by

jury, and in such action all statutes of the United

States modifying or extending the common-law right

or remedy in cases of personal injury to railway em

ployees shall apply * * *”

4

45 U. S'. C. Sec. 51 provides:

“Every common carrier by railroad while engaging

in commerce between any of the several States * * *

shall be liable in damages to any person suffering

injury while he is employed by such carrier in such

commerce, or, in case of the death of such employee

* * * for such injury or death resulting in whole or

in part from the negligence of any of the officers,

agents, or employees of such carrier, or by reason of

any defect or insufficiency, due to its negligence, in its

* * * equipment * * # ’ ’

Sec. 54 provides:

‘ ‘ That in any action brought # * * by virtue of any of

the provisions of this chapter to recover damages for

injuries to, or the death of, any of its employees, such

employee shall not be held to have assumed the risks of

his employment in any case where such injury or death

resulted in whole or in part from the negligence of any

of the officers, agents, or employees of such carrier;

and no employee shall be held to have assumed the

risks of his employment in any case where the violation

* * * of any statute enacted for the safety of employees

contributed to the injury or death of such employee.”

Statement

Plaintiff, a seaman, 52 years old, obtained a judgment in

the United States District Court, Southern District of New

York (Thomas F. Murphy, D. J.) for $15,000 damages and

$75 costs, for injury sustained in an assault on him on

shipboard in the quarters and during the time assigned to

him for rest between watches, committed by another sea

man, Hunter, assigned to the same quarters.

The defendant appealed to the Court of Appeals, Second

Circuit, and filed a designation (R. 20) which did not

5

include any of the evdience, nor any condensed statement

in narrative form of all or part of the testimony, nor any

statement of points, pursuant to the Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure, Rule 75, paragraphs c, d and g, nor does the

record contain such a statement, under Rule 76. Plaintiff

cross-appealed from the dismissal of the complaint as to

negligence in Conclusion of Law No. 1 and inadequacy.

The record contains the following (R. 10-17) :

‘‘F in d in g s on F act

“ 1. That plaintiff has been a seaman for 32 years

and signed articles on the defendant’s S. S. Frederick

Lykes at Houston, Texas, for a foreign voyage to the

Far East which consumed about four months’ time.

“ 2. Aboard ship he shared quarters with two fellow

seamen, including Hunter, his assailant. Through the

entire course of the voyage to the Far East and return

there was no trouble between plaintiff and Hunter.

In fact plaintiff described their relationship as

‘friendly.’ There was testimony, however, that on a

single occasion in the Philippines Hunter had an argu

ment with a fellow crew member but no blows were

struck by either.

“ 3. On the evening of the assault, May 25, 1949,

when the ship had returned to Galveston, Texas, plain

tiff and Hunter had a can of beer together ashore and

left each other under amicable circumstances. Plain

tiff returned to the ship and went to sleep since his

watch did not begin until 12 midnight. He reported

for duty in the fireroom of the S. S. Frederick Lykes

at a few minutes before midnight. Hunter, who had

the 8 to 12 watch in the same fireroom, told him every

thing was in order and left, presumably for his quar

ters.

“4. Plaintiff did not find everything in order. There

were no notations on the blackboard concerning the

tips in the burner and some oil had been spilled on the

6

deck. The ship was being maneuvered to go upstream

to Houston. Plaintiff inquired of the junior engineer

what size tips Hunter had used and got no satisfactory

answer.

“ 5. A few minutes later Hunter returned to the fire-

room and shouted some vile remarks at plaintiff.

Hunter told plaintiff that he had been firing long

enough to know wdiere things were. This argument

was broken up by the chief engineer, who told Hunter

to go back to his quarters. No blows were struck—-

in fact there was no physical contact at all.

‘ ‘ 6. Later that same morning after the plaintiff had

completed his watch and returned to his quarters he

was suddenly and without provocation beaten by

Hunter. As a result plaintiff sustained severe injuries

to his hip. These injuries caused plaintiff to be con

veyed by ambulance that day to a hospital in Houston

and from there to the Marine Hospital in G-alveston.

# * #

“ 11. The injuries that plaintiff sustained consisted

of a fracture of the neck of the right femur. A pin

placed through the femur to keep that bone in place

was subsequently removed. Later the shaft of the

femur was broken by surgeons in order to align it bet

ter. At that time a metal plate was placed in the

femur, which remains to the present. Plaintiff walks

with the aid of a cane and is presently suffering

pain. # # #

“ D iscussion

* there is no evidence that the shipowner was

aware of any propensity of Hunter’s to assault fellow

employees, either at the time Hunter was hired or at

7

any other time prior to the assault on the plaintiff

. * * # In this case however there is no evidence of

any appreciable probability of such assault by hiring

or retaining Hunter. * * *

“ * * * But neither the situation of a justified or

sufficiently provoked intentional battery are presented

by the evidence in this ease. And the evidence being

uncontradicted that plaintiff’s injuries were intention

ally caused by the blows of Hunter, a fellow seaman,

the plaintiff may recover for breach of seaworthi

ness.

“ CowCLtrsioisrs on Law

“ 1. The plaintiff has failed to prove negligence on

the part of the defendant and the complaint in this

regard should be dismissed.

“ 2. Because of the assault and battery on the

plaintiff by Hunter the plaintiff is entitled to be in

demnified for the defendant’s breach of its warranty

of seaworthiness in the sum of $15,000.”

The Court of Appeals (Swan, Ch. J., L. Hand and

Augustus N. Hand, Ct. JJ .) did not have before it nor re

view the evidence, nor consider whether nor determine

therefrom that the finding of unseaworthiness was

clearly erroneous under Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,

Rule 52. It, nevertheless, reversed the judgment and dis

missed the complaint with an opinion by L. Hand, J. on

June 4, 1953. It held that “ it will not be necessary to

notice” plaintiff’s cross-appeal.

On June 17, 1953, petitioner filed with the said Court

a petition for rehearing, which was summarily denied

without opinion on June 19, 1953.

8

Specification of Errors

The Court of Appeals erred:

1. In failing to give effect to the duty of defendant to

provide and secure to plaintiff safe quarters and oppor

tunity for rest therein in safety between watches, and to

the violation of such duty through the action of defend

ant’s employee, Hunter, in assaulting plaintiff without

provocation on shipboard in the quarters and during the

time assigned to plaintiff for rest.

2. In holding defendant not liable for the unprovoked

assault of plaintiff by defendant’s employee, Hunter, in

the quarters and during the time assigned to plaintiff for

rest on shipboard between watches.

3. In holding, in effect, that plaintiff assumed the risk

of unprovoked assault by defendant’s employee, Hunter,

in the quarters and during the time assigned to plaintiff

for rest on shipboard between watches.

4. In reversing the .District Court’s determination of

unseaworthiness without having before it or considerng

the evidence on which such determination was based, or

determining therefrom whether such determination was

clearly erroneous, and without defendant having stated

any such point in its designation.

5. In holding it unnecessaary to notice plaintiff’s cross-

appeal, and refusing to notice, consider and determine the

questions of defendant’s liability for “ negligence” of de

fendant’s officers, agents and employees and inadequacy

of damages presented by such cross-appeal.

9

Reasons for Granting the Writ*

I. Respecting unseawortliiness, the Court of Appeals,

and respecting negligence, both courts have failed to give

effect to plaintiff’s right to and defendant’s duty to pro

vide, and its warranty of, safe quarters and opportunity

for rest therein in safety between watches, and the con

sequent duty of Hunter, as an employee of defendant, as

signed to the same quarters as plaintiff, to so conduct

himself as to secure to plaintiff his right to safe quarters

and opportunity for safely resting therein between watches.

The decision has burdened plaintiff with assumption of the

risk of unprovoked assault in such quarters by such other

seaman assigned to the same quarters. This violates and

conflicts with the provisions and the results or the prin

ciples of the following statutes and decisions.

(a) By statute, as by maritime law, unseaworthiness in

cludes being “ otherwise unfit in her crew, body, tackle,

apparel, furniture, provisions, or stores” (46 U. S. C. Sec.

653); every vessel must have “ suitable accommodations

for * * * the crew * * * with safety to life” (46 IT. S. C.

Sec. 391); “ crew quarters * # * properly ventilated and in

a clean and sanitary condition” (46 U. S. C. Sec. 660a);

“ a space of not less than one hundred and twenty cubic

feet and not less than sixteen square feet, measured on

the floor or deck of that place, for each seaman or appren

tice lodged therein, and each seaman shall have a separate

berth * * * ■ sneh place or lodging shall be securely con

structed, properly lighted, drained, heated, and ventilated,

properly protected from weather and sea, and, as far as

practicable, properly shut off and protected from the

effluvium of cargo or bilge water” (46 IT. S. C. Sec. 660-1);

“ space allotment for lodgings” {Idem. ) ; “ a safe and warm

* This summary of reasons is submitted also as petitioner’s brief

or argument.

10

room for the use of seamen in cold weather” (46 U. S. C.

Sec. 669); and “ firemen # * divided into at least three

watches, which shall he kept on duty successively” (46

TT. S. C. Sec. 673).

In Aguilar v. Standard Oil Go. of N. J 318 U. S. 724,

728, 729, 731-732, 734, this Court held that these statutory

provisions, “ designed to secure the comfort and health of

seamen aboard ship” and “ recognizing the shipowner’s

duty * * * do not create the duty. That existed long before

the statutes were adopted. They merely recognize the

pre-existing obligation and put specific legal sanctions,

generally criminal, behind it * * * The legislation therefore

gives no ground for making inferences adverse to the

seaman or restrictive of his rights * * * Rather it furnishes

the strongest basis for regarding them broadly, when an

issue concerning their scope arises * * * Unlike men em

ployed in service on land, the seaman, when he finishes

his day’s work, is neither relieved of obligations to Ms

employer nor wholly free to dispose of his leisure as he

sees fit. Of necessity, during the voyage he must eat,

drink, lodge and divert himself within the confines of the

ship. In short, during.the period of his tenure the vessel

is not merely his place of employment, it is the framework

of his existence * * * In sum, it is the ship’s business which

subjects the seaman to the risks attending hours of relaxa

tion in strange surroundings. Accordingly it is but rea

sonable that the business extend the same protections

against injury from them as it gives for other risks of the

employment” (318 U. S. 728, 729, 731-732, 734).

(b) In respect to these duties fellow-seamen are not

fellow-servants, but each is the agent of the owner, who

is liable for their violations of a duty of the owner (Scarf

v. Metcalf, et al., 107 N. Y. 211); such duty being “ imposed

by the law itself as one annexed to the employment”

(Cortes v. Baltimore Insular Line, 287 U. S. 367, 371), and

being “ non-delegable and not qualified by the fellow-servant

rule” (Mahnich v. Southern S. S. Co., 321 U. S. ,96, 102).

11

(c) Provision and maintenance as a part of the owner’s

warranty and duty are not limited to maintenance and

cure after injury; for, as this Court has pointed out, under

both the maritime law and the Jones Act (46 U. S. €. Sec.

688) and Employers’ Liability Act (45 U. S. C. Sec. 51) a

shipowner would be liable for damages, for example, in

“ the case of a seaman who is starved during the voyage

in disregard of the duty of maintenance with the result that

his health is permanently impaired” (Cortes v. Baltimore

Insular Line, 287 U. S. 367, 373), or if unwholesome food

is served aboard ship, causing injury to a seaman (U. S.

S. B. E. F. C. v. Greenwald, 2 Cir., 16 F. 2d 948).

Specifically as to quarters and right of safe relaxation

and rest, a shipowner has been held liable under the Jones

Act (46 U. S. C. Sec. 688) and Employers’ Liability Act (45

U. S. C. Secs. 51, 54)—and it would seem would be equally

liable under the maritime law—for damages for assault

by another member of the crew on plaintiff in the quarters

assigned to him on shipboard (Boudoin v. Lykes Bros. S. 8.

Co., E. D. La., 112 F. Supp. 177, 180); for tuberculosis con

tracted “ while occupying the sleeping quarters provided

for him on board ship” due to their dampness and im

proper ventilation (McCall v. Inter Harbor Navigation Co.,

154 Or. 252, 258) or through the failure to provide “ safe”

quarters aboard ship, due to a leaky valve of a radiator

spraying dampness on a seaman’s berth (Booker v. Alaska

8. S. Co., 185 Wash. 71, cert, denied 299 U. S. 552); and for

contagious itch contracted by a seaman aboard ship from

another member of the crew (Compton v. Hammond Lum

ber Co., 153 Or. 546, 555). The Ninth Circuit in Sundberg

v. Washington Fish & Oyster Co., 9 Cir., 138 F. 2d 801, held

that the issue as to plaintiff’s claim for damages was for

the jury and the complaint had been erroneously dismissed

where plaintiff, while off duty was injured by a bullet fired

by another member of the crew* at sea lions for sport.

In The Lord Derby, E. D. La., 17 Fed. 265, Judge Pardee

in 1883 held a vessel liable in rem for damages where a

12

pilot was bitten by a dog chained under the cabin table

“ because the cabin was the place where the libellant had

been assigned to sleep, had slept, where his baggage was

placed, and where he had a right to go and did go for i t ”

(17 Fed. 266).

The decision herein thus conflicts in principle with each

of the foregoing decisions.

(d) In Lillie v. Thompson, 332 U. S. 459, this Court, per

curiam, reversed dismissal and sustained a complaint

against a railroad where a criminal assault was committed

by a stranger on a woman employed by defendant as a

night depot agent, because there was “ a duty to make

reasonable provision against i t” and “ Breach of that duty

would be negligence, and we cannot say as a matter of law

that petitioner’s injury did not result at least in part from

such negligence” (332 U. S. 462). And where an employee,

charged with any part of the duty to provide safe quarters,

himself commits the assault, his act in violation of such

duty is further independent ground for liability. Boudoin

v. Lyles Bros. 8. 8. Co., E. D. La., 112 F. Supp. 177, 178,

where a seaman was assaulted in his bed by another sea

man. Compare Compagnie Generate Transatlantique v.

Rivers, 2 Cir., 211 Fed. 294, cert, denied 232 U. S. 727,

holding a steamship company liable for assault by a mem

ber of the crew upon a passenger in the quarters assigned

to her aboard ship.

(e) The 1939 amendment to the Euployers’ Liability Act

(53 Stat. 1404, c. 685, 45 U. S. C. Sec. 54) obliterated from

the law every vestige of the doctrine of assumption of risk

(Tiller v. Atlantic Coast Line R. Co., 318 U. S. 54, 58).

This applies to seamen under the Jones Act, and “ Thus

the shipowner becomes liable for injuries to a seaman

resulting in whole or in part from the negligence of another

employee” , as unqualifiedly and completely as for negli

gence of an officer or agent of defendant. “ AYhile the acts

13

of negligence underlying such accidents may reach higher

into the management hierarchy, the Federal Employers’

Liability Act compels us to go no higher than a fellow

servant” (Johnson v. TJ. 8., 333 U. S. 46, 49).

The decision herein conflicts with this Court’s interpreta

tion of the statutes in the Tiller and JoJmson cases, for the

‘Court of Appeals refused even to consider defendant’s

liability for the acts of Hunter and thus burdened plaintiff

with assumption of the full risk of unprovoked assault by

Hunter in the quarters assigned to plaintiff for rest.

(f) In Reck v. Pacific-Atlantic S. S. Co., 2 Cir., 180 F. 2d.

866, the Court affirmed a judgment for $46,000 damages and

$1,836 maintenance and cure where a seaman, suffering

from delirium tremens two days after leaving port due to

severe alcoholic intoxication while in port, and put to bed

in his quarters aboard ship, got up and left his quarters

and fell into an open hatch when Tackett, another crew

member assigned to guard him, thought him asleep and left

him unguarded about five minutes while going to the lava

tory fifteen feet away. The. Court pointed out that “ the

watch was then changing and Tackett could have obtained

relief for a moment” (180 F. 2d 868). In McDonough v.

Buckeye 8. 8. Co., D. C. N. D. Ohio, 103 F. Supp. 473, affd.

Buckeye Steamship Company v. McDonough, 6 Cir., 200

F. 2d 558, cert, denied 345 U. S, 926, the Courts gave plain

tiff judgment for death of Kerr, a seaman who, while

drunk, was left briefly on a dock eighteen feet wide where

he fell and could not be lifted by Cox, a seaman assigned

to assist him to the ship, and drowned while Cox went

aboard ship and reported. It was held that “* * * the

conclusion is inescapable that Cox disregarded his duty

and failed to act as a reasonable man of ordinary pru

dence” (103 F. Supp. 477).

In light of the Reck and McDonough cases, the decision

herein means that while the company through its employees

14

owes a duty to a drunk, no duty is owed to a sober seaman

who has just come off watch, and he assumes the risk of

being assaulted and crippled for life in the quarters as

signed to him for rest, committed without provocation by

a seaman assigned to share the same quarters.

(g) But here, with Hunter assigned to share quarters

with plaintiff—and when told by the chief engineer to go

back to his quarters, where he then awaited and assaulted

plaintiff (R. 11)—Hunter was charged with and violated

duty as defendant’s employee, indeed the very duty of de

fendant, to allow and secure to plaintiff safe enjoyment

of such quarters and the opportunity to rest therein in

safety upon coming off watch; duty as positive as were the

duties of Tackett, Cox, Varner and Lamure, violated in the

Reck (180 F. 2d 866), McDonough (103 F. Supp. 473, affd.

200 F. 2d 558), Simdberg (138 F. 2d 801) and Rivers (211

Fed. 294) cases supra. “ He was the representative of

principal duties of the defendant” (Brown v. Pacific Coal

Co., 241 U. S. 571, 573).

It was the act of the junior engineer in communicating

with Hunter which had aroused Hunter; then in the

engine room plaintiff enjoyed protection from the chief

engineer (R. 11, pars. 4 and 5); but in the quarters assigned

to him and Hunter, as the findings indicate, he could look

only to Hunter for safety, and was helpless when Hunter,

in violation of duty, assaulted him (R. pp. 10, 11, pars. 2

and 6).

(h) Jamison v. Encarnacion, 281 U. S. 635 and Alpha

Steamship Corporation v. Cain, 281 U. S. 642 establish

that, given a duty, its violation by assault is equally

“ negligence” as is a violation of duty by any less willful

act or default, this Court saying:

“ As unquestionably the employer would be liable if

plaintiff’s injuries had been caused by mere inad

vertence or carelessness on the part of the offending

foreman, it would be unreasonable and in conflict with

15

the purpose of Congress to hold that the assault, a

much graver breach of duty, was not negligence within

the meaning of the Act” (281 U. S. 641).

This definition of negligence as including assault is as

applicable to the assault by Hunter here as to that by the

foreman in the Jamison case, because defendant’s duty

here was owed through Hunter as fully as through the

foreman in the Jamison case.

(i) The Second Circuit Court of Appeals itself reversed

a dismissal in Nelson v. American-West African Line, 2

Cir., 86 P. 2d 730, cert, denied 300 U. S. 665, where a boats

wain entered the crew’s quarters and assaulted a seaman

in his bunk; affirmed recoveries in Koehler v. Presgue-Isle

Transp., Co., 2 Cir., 141 P. 2d 490, where a fellow-seaman

Todd assaulted plaintiff on the ladder and then on deck

when plaintiff was returning from shore leave, and in

Kyriakos v. Goulandris, 2 Cir., 151 P. 2d 132, where a fel

low seaman Bouritis assaulted plaintiff about a mile from

the ship while plaintiff was returning from shore leave;

and reversed a dismissal in Keen v. Overseas Tankship

Corp., 2 Cir., 194 F. 2d 515, cert, denied 343 U. S. 966,

where a fellow-seaman Mruczinski assaulted plaintiff on

deck when they had just returned from shore leave. In

Koehler, the Court (Frank, J. writing) said of “ negli

gence” that “ We think that it includes any knowing or

careless breach of any obligation which the employer

owes to the seamen. Among those obligations is that of

seeing to the safety of the crew” (141 P. 2d 491). In

Kyriakos, noting that “ Bouritis was hidden behind the

corner of a building * * * to ambush the libellant,” the

Court (Augustus N. Hand, J., writing) pointed out that

“ Seamen have no legal power to rid themselves of dan

gerous shipmates” (151 P. 2d 135).

The Nelson, Koehler and Kyriakos cases, correct in

rsult, conflict in result with the case at bar.

16

(j) But the Nelson, Koehler and Kyriakos cases con

tain erroneous reasoning or theme, and the Court of Ap

peals purportedly gives effect herein to the erroneous

reasoning instead of the correct result of these cases, in

refusing to follow their result to sustain the recovery

herein. This “ confusion which has developed in the ap

plication of the two statutes” (Carter v. Atlantic <& Saint

Andrews Bay By. Co., 338 U. S. 430, 431) in assault cases

makes doubly important a review to clarify and determine

in the case at bar the points really justifying recovery.

Thus, in Nelson, although the assault of Nelson in his bunk

during rest between watches clearly established a violation

by the boatswain of defendant’s duty to secure to Nelson

safe quarters and opportunity for rest in safety between

watches,—and the Court itself stated that “ In truth it was

at best an act of wanton tyranny to get him out of his

bunk at that time, to say nothing of the violence used in

effecting i t”—the Court nevertheless erroneously said

of the boatswain’s assault that “unless there was

some evidence that he supposed himself engaged upon the

ship’s business the ship was not liable” (86 F. 2d 732).

And although the Court stated that “ the boatswain was

blind drunk, and through his clouded mind all sorts of

vague ideas may have been passing; the fact that he had

made himself incompetent to further the ship’s business

was immaterial” , the Court seized upon the bare fact that

“ he told him not only to get up, but to ‘turn to’ ” as being

“ some evidence that he meant to act for the ship.” The

Court then states the astounding doctrine that, “ however

imbecile his conduct” , the boatswain’s drunken use of

these two words “ turn to” spelt the difference between lia

bility of defendant or assumption by Nelson of the risk of

assault in his bunk;—that the same assault, in identical

detail except lacking use by a drunk of the words “ turn

to” , would have required that Nelson bear the risk and

the injury, and that the company be held not liable.

This reasoning in the Nelson case, and that herein,

ignores the violation of the duty to provide safe quar

17

ters and opportunity for rest in safety between watches,

and also is in conflict with Boudoin v. Lykes Bros. S. S.

Co., E. D. La., 112 F. Supp. 177, a District Court decision

in the Fifth Circuit, and in conflict with this Court’s defini

tion of negligence in the Jamison and Cain eases, and as

sumption of risk rulings in the Tiller and Johnson cases.

Then, in Kable v. United States, 2 Cir., 169 F. 2d 90,

where the chief officer was assaulted by the chief engineer,

the Second Circuit, holding the defendant not liable, stated

it distinguished the Nelson, Cain and Jamison cases as

having “ no application here, for in each the assault was

committed by a superior officer on an immediate inferior”

and were “ directly related to the doing of the ship’s

work” (169 F. 2d 92). The Koehler (141 F. 2d 490),

Kyriakos (151 F. 2d 132) and Keen (194 F. 2d 515) cases,

though correctly sustaining liability for assault by a fel

low-seaman, ignore as the basis of liability the assaulting

seaman’s violation of duty, and emphasize rather only

the negligence of “ officers” in hiring or retaining dan

gerous men (141 F. 2d 491; 151 F. 2d 135; 194 F. 2d 516)

and consequent unseaworthiness (194 F. 2d 518).

This particular aspect of the Nelson, Kable, Koehler,

Kyriakos and Keen decisions of the Second Circuit, of

course, is directly contrary to this Court’s holding in

Johnson v. United States, 333 U. S. 46, 49, that the Act

“ compels us to go no higher than a fellow servant.”

But following this particular theme of its own assault

decisions, rather than their results and the doctrine of this

Court’s decisions, the Court of Appeals now holds herein

that “ every workman is apt to be angry when a fellow

complains of his work to their common superior; * * *

Sailors lead a rough life and are more apt to use their

fists than office employees; * * * when a man’s blood is up,*

* There is no finding that plaintiff “complained” ; but to whom

should he complain if not to an officer? It was the junior engineer

who got Hunter’s “blood up.”

18

lie will go farther than he should; * * * Such a set-to

seldom results in serious injury when only fists are used,

# * # We are not satisfied that the findings proved that

Hunter was a man unfit to serve.” This is the language

of assumption of risk,* now completely obliterated from

the law. Moreover, the negligent servants were not held

unfit to serve but to have violated duty in Tiller v. Atlantic

Coast Line R. Co., 318 U. S. 54, Johnson v. II. 8., 333 IT. S.

46, and Anderson v. Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Ry.

Co., 333 U. S. 821. Tackett, Cox and Varner were not un

fit to serve but violated duty in the Reck (180 F. 2d 866),

McDonough (103 F. Supp. 473, affd. 200 F. 2d 558) and

Sundberg (138 F. 2d 801) cases. Seldom would Tackett’s

going to the lavatory, or Cox’s briefly leaving a man he

could not carry or Varner’s shooting at sea lions cause

injury or death as in the Reck, McDonough and Sundberg

cases.

(k) The decision herein, if allowed to stand, will mean,

in its effect, that in assault cases the word ‘‘employee” is

to be ignored or excised from both the liability and as

sumption of risk sections of the Federal Employers’

Liability Act (45 U. S. C. Secs. 51 and 54), as incorporated

in the Jones Act (46 U. S. C. Sec. 688); that despite the

use in the statute of the word “ employees” equally with

“ officers”, a seaman assumes the risk of any assault not

committed by an “ officer” or not due to an “ officer’s”

negligence in hiring an unfit man, and that the seaman as

sumes the risk of quarters made unsafe by conduct of a

fellow seaman assigned to share the quarters. The con

flict and confusion require review (Cf. Carter v. Atlanta

& Saint Andrews Bay Ry. Co., 338 TJ. S. 430, 431); the de

cision is too important not to review, too erroneous not to

reverse.

* Compare for similarity of reasoning and ruling Baltimore &

Ohio RR. Co. v. Baugh, 149 U. S. 368, decided in 1893; fifteen

years before enactment of the Employers’ Liability Act and twenty-

seven years before the Jones Act.

19

II. The reversal of the determination of unseaworthiness,

on the record herein, violates Fed. Rules of Civ. Proc.,

Rules 52, 75 and 76, and conflicts with the following deci

sions of this Court and the highest judicial authority of

England which have consistently held that the issue of

unseaworthiness is an issue of fact, and the determination

by Court or jury of unseaworthiness (or seaworthiness)

is a finding of fact (Maknich v. Southern Steamship Co.,

321 U. S. 96, 98; Luckenbach v. W. J. McCahan Sugar Re

fining Co., 248 IT. S. 139, 145; W. J. McCahan Sugar Re

fining Co. v. S. S. Wildcroft, 201 IT. S. 378, 387; The Carib

Prince, 170 U. S. 655, 658; Steel v. State Line S. S. Co.,

L. R, 3 App. cas. 72, 81, 82, 84, 86, 90, 91).

The single defective rivet in the peak tank in The Carib

Prince, and the insecurely latched port in Steel v. State

Line S. S. Co., would have been immaterial with cargoes

of marble or teakwood but supported fact finding of un

seaworthiness with the cargoes of bitters and wheat.

Maknich v. Southern Steamship Co. states unseaworthiness

includes being—even due to the act of a fellow servant—

“ inadequate for the purpose for which it was ordinarily

used” (321 IT. S. 103, 104). The argument of availability

of good rope was inappropriate “ because * * * it was the

stage which was unseaworthy” (321 IT. S. 104). See also

Carlisle Packing Co. v. Sandanger, 259 IT. S. 255. Unsea-

worthiness is relative to the facts and evidence of each

ease.

Here, the condition—the “ seaworthiness” or “ unsea

worthiness”—of the quarters assigned to plaintiff, in

cluded the assignment of Hunter to share such quarters.

In turn, the fitness or “ seaworthiness” or “ unsea

worthiness” of Hunter included not merely his qualifica

tions or fitness as a member of a crew, but his fitness as

a part of the quarters assigned to plaintiff. As with negli

gence (Johnson v. United- States, 355 IT. S. 46, 48), so, we

submit, with unseaworthiness (Cf. Carlisle Packing Co. v.

20

Sandanger, swpra) res ipsa loquitur applies in determining

this factual issue; the question whether the injury was

“ in fact the result of causes beyond the defendant’s

responsibility” was a factual question (Gleeson v. Virginia

Midland B. B. Co., 140 U. S. 435, 444; Terminal B. Assn, of

St. Louis v. Stangel, 8 !Cir., 122 F. 2d 271, 276, cert, denied

314 U. S. 680, cited in Johnson v. United States); and all

the evidence was involved in its determination.

The District Court’s judgment for plaintiff was based

upon its determination of unseaworthiness from “ the

evidence in this case” (R. 16, fol. 48). The Court of

Appeals, however, did not have before it “ the evidence

in this case” ; it had only the District Court’s decision

containing findings and conclusions. Under Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure, Rules 75 and 76, defendant in ap

pealing did not designate any part of the evidence, nor

a condensed statement in narrative form of all or part

of the testimony, nor a statement of points (Rule 75,

pars, (c), (d) and (g)), nor does the record contain such

a statement (Rule 76). If defendant intended contesting

the factual determination of unseaworthiness, plaintiff

was entitled to notice of this, and to the right to have

the evidence included.

Defendant thus was in no position to contend that, and

the Court of Appeals had nothing from which it could

consider whether, the determination of unseaworthiness

as a finding of fact was clearly erroneous. Under Rule

52 “ Findings of fact shall not be set aside unless clearly

erroneous.” This is to be determined “ on the entire evi

dence” (United States v. United States Gypsum Co., 333

U. S. 364, 395). See also 5 Moore’s Federal Practice, 2d

Ed., pages 2611-2629 and cases cited. The Court of Appeals

did not consider the evidence nor purport to determine

therefrom that the finding was “ clearly erroneous.”

21

Its decision thus conflicts with the foregoing decisions

and violates the foregoing rules; and the question is a

most important one affecting appeals from judgments in

personal injury actions (Cf. United States v. Gypsum Co.,

333 U. S. 364-).

III. The District Court’s ruling as to negligence, how

ever, was solely as a conclusion of law (R. 17), based upon

no showing that the shipowner was aware of any pro

pensity of Hunter’s to assault fellow employees (R. 13).

But this ignored as matter of law the theory of plain

tiff’s case. Contrary to Johnson v. United States, 333

U. S. 46, 49, both Courts herein, as matter of law, have

looked only “ higher than a fellow servant.”

Both Courts also have ignored the fact that both the

Chief Engineer and junior engineer were aware of (and

apparently occasioned) Hunter’s wrath and his attempted

assault of plaintiff in the engine room.

Contrary to the authorities noted under I, supra, both

Courts have ignored also the non-delegable duty of de

fendant to provide plaintiff safe quarters and oppor

tunity to rest in safety between watches.

The findings as to unseaworthiness equally establish

“ negligence” in these respects sufficient to support the

District Court’s judgment on this ground as distinct

from the bare ground of “ unseaworthiness” (Alpha

Steamship Corporation v. Cain, 281 U. S. 642; Carlisle

Packing Co. v. Sandanger, 259 U. S. 255). Plaintiff cross-

appealed to present these questions, as well as the in

adequacy of damages. It consequently was error—in

deed, a denial of due proces of law—for the Court of Ap

peals to hold that “ it will not be necessary to notice his

appeal.” This itself is so important as to require review

(Cf. Alpha Steamship Corporation v. Cain; Carlisle Pack

ing Co. v. Sandanger, stipra; Busynski v. Luckenbach

Steamship Co., 277 U. S. 226).

22

CONCLUSION

The decision of the Court below involves questions

of the greatest importance to seamen, upon which the

Court of Appeals clearly erred; questions of the great

est importance respecting appellate practice, upon

which said Court also clearly erred; and impressive

conflict upon all questions with decisions of this and

other high Courts; and a writ of certiorari should be

granted and the case should be reviewed and reversed

by this Court.

Dated, New York, N. Y., July 31, 1953.

Respectfully submitted,

Charles A ndrews E llis,

Counsel for Petitioner.

S ilas Blake Axtell,

Charles A ndrews E llis,

Martin G. Stein ,

of Counsel.

[6599]