Booker v. Tennessee Board of Education Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1956

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Booker v. Tennessee Board of Education Brief for Appellants, 1956. 52d3b916-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/55859656-690f-4506-abc3-fcc7d348ec45/booker-v-tennessee-board-of-education-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

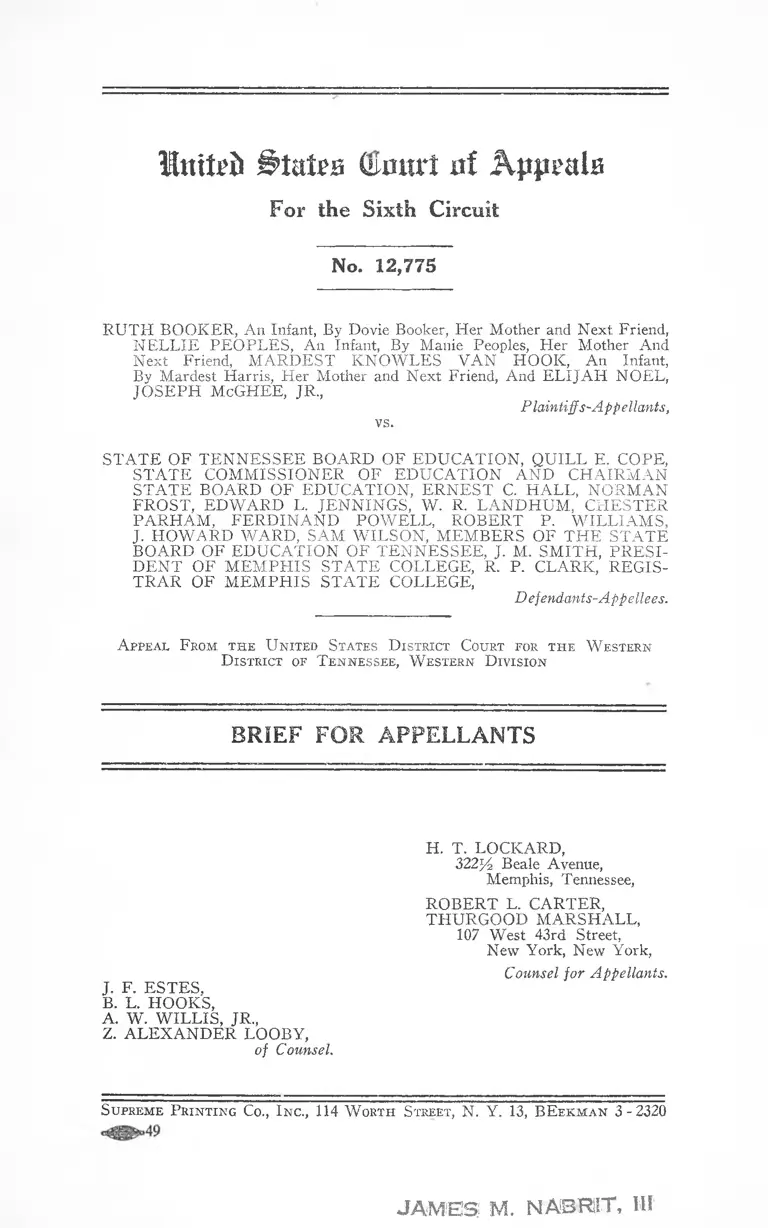

United States (uuul at Appeals

For the Sixth C ircuit

No. 12,775

RUTH BOOKER, An Infant, By Dovie Booker, Her Mother and Next Friend,

NELLIE PEOPLES, An Infant, By Manie Peoples, Her Mother And

Next Friend, HARDEST KNOWLES VAN HOOK, An Infant,

By Hardest Harris, Her Mother and Next Friend, And ELIJAH NOEL,

JOSEPH McGHEE, JR.,

P laintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

STATE OF TENNESSEE BOARD OF EDUCATION, QUILL E. COPE,

STATE COMMISSIONER OF EDUCATION AND CHAIRMAN

STATE BOARD OF EDUCATION, ERNEST C. HALL, NORMAN

FROST, EDWARD L. JENNINGS, W. R. LANDHUM, CHESTER

PARHAM, FERDINAND POWELL, ROBERT P. WILLIAMS,

J. HOWARD WARD, SAM WILSON, MEMBERS OF THE STATE

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF TENNESSEE, J. M. SMITH, PRESI

DENT OF MEMPHIS STATE COLLEGE, R. P. CLARK, REGIS

TRAR OF MEMPHIS STATE COLLEGE,

Defendants-Appellees.

A ppeal F rom the U nited States D istrict Court for the W estern

D istrict of Tennessee, W estern D ivision

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

H. T. LOCKARD,

322y2 Beale Avenue,

Memphis, Tennessee,

ROBERT L. CARTER,

THURGOOD MARSHALL,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York, New York,

J. F. ESTES,

B. L. HOOKS,

A. W. WILLIS, JR.,

Z. ALEXANDER LOOBY,

of Counsel.

Counsel for Appellants,

Supreme Printing Co., I nc., 114 W orth Street, N. Y. 13, BEekman 3-2320

JAM ES M. NAI3RIT, III

1

Statem ent of Questions Involved

1. Did the court below have jurisdiction to hear and de

termine this cause or was it a matter which should

have been heard and determined by a three-judge court

pursuant to Title 28, United States Code, Sections 2281

and 2284.

The court below answered the question No.

Appellants contend the answer should have been Yes.

2. Are appellants entitled to an order requiring their im

mediate admission to Memphis State College?

The court below answered the question No.

Appellants contend the answer should have been Yes.

Ill

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Statement of Questions Involved ............................. i

Statement of Facts .................................................. 1

Argument ................... 7

I—Did the court below have jurisdiction to hear

and determine this cause or was it a matter

which should have been heard and determined

by a three-judge court pursuant to Title 28,

United States Code, Sections 2281 and 2284.. 7

II—Are appellants entitled to an order requiring

their immediate admission to Memphis State

College? .......................................................... Ip

Relief .......................................................................... 14

Conclusion ................................................................ 15

T able of Cases

Bell v. Rippy, 133 F. Supp. 811 (N. D. Tex. 1955) .. 8

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 ............................... 7

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 ............. 7

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 __ 12

Chapman v. Boynton, 4 F. Supp. 43 (D. C. Kans.

1933) ...................................................................... 8>9

Ex Parte Metropolitan Water Co., 220 U. S. 539 .. 8, 9

Ex Parte Poresky, 290 U. S. 3 0 ......................... 9

Frazier v. Board of Trustees, 133 F. Supp. 598

(M. D. N. C. 1955) ...............................................7, 9,12

Grant v. Taylor, Civil Action No. 6404 (W. D. Okla.

1955), unreported.................................................. 12

IV

PAGE

Gray v. Board of Trustees of University of Tennes

see, 342 U. S. 517 .................................................. 12

Lucy v. Adams, — U. S. —, Oct. 10, 1955 ................ 12

McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F. 2d 949 (CA 4th

1951), cert, denied, 341 U. S. 591 ......................... 11

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637 11

Mitchell v. Board of Regents of the University of

Maryland, Docket No. 16, Folio 126 (Baltimore

City Court 1950), unreported............................... 12

Norumbega Co. v. Bennett, 290 U. S. 598 ................ 8,, 9

Parker v. University of Delaware, 75 A. 2d 225

(Del. 1950) ............................................................. 11

Robinette v. Campbell, 115 F. Supp. 699 (N. D. Atl.

1951), 342 U. S. 940 ............................................... 9

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 641.............. 11

State of Florida ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of Control,

80 So. 2d 20 (1955) ............................................... 12

Swanson v. University of Virginia, Civil Action

No. 30 (W. D. Va. 1950), unreported.............. .. 12

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 .............................. 11

Troullier v. Proctor, Civil Action No. 3842 (E. D.

Okla. 1955), unreported ........................................ 12

Tureaud v. Board of Supervisors, 116 F. Supp. 248

(E. D. La. 1953), reversed, 207 F. 2d 807 (CA 5th

1953), vacated and remanded, 347 U. S. 971, orig

inal judgment reinstated by the district court and

affirmed on appeal, 225 F. 2d 434, reversed on re

hearing, 226 F. 2d 714, judgment on rehearing

vacated and hearing ordered en banc, and the orig

inal judgment of the Court of Appeals affirming

the judgment of the lower court reinstated, — F.

2d —, Jan. 6, 1956 ...............................................8,10,12

V

PAGE

Unexcelled Chemical Co. v. United States, 345 U. S.

59 ................................................................................ 10

United Drug Co. v. Graves, 34 F. 2d 808 (M. D. Ala.

1929) ...................................................................... 8,9

United States v. Congress of Industrial Organiza

tions, 335 U. S. 106..................................................... 10

United States v. Universal C.I.T. Credit Corp., 334

U. S. 218 ................................................................. 10

Wells v. Dyson, Civil Action No. 4679 (E. D. La.

decided Apr. 2, 1955), unreported............................. 12

Wells v. Walker, — F. Supp. — (W. D. Ky. 1955) 8

White v. Smith, Civil Action No. 1616 (W. D. Texas,

decided July 28, 1955), unreported....................... 12

Whitmore v. Stillwell, — F. 2d — (CA 5th decided

Nov. 3, 1955) ........................................................ 12

Wichita Falls Junior College District v. Battle, 204

F. 2d 632 (CA 5th 1953), cert, denied, 347 U. S. 974 11

Wilson v. Board of Supervisors, 92 F. Supp. 986

(E. D. La. 1950), aff’d 340 U. S. 906 .................. 11

Wilson v. City of Paducah, 100 F. Supp. 116 (W. D.

Ky. 1951) ............................................................... 12

O ther A uthorities

Hart and Wechsler, “ The Federal Courts and the

Federal System,’’ 852 (1953) ................ 9

Johnson and Washington, “ One or Three—Which

Shall It Be?” 1 How. L. Rev. 194, 218 (1955) . . . . 9

Im ttb IS'tate ( ta r t of Appeals

For the Sixth C ircuit

No. 12 ,775

-------------------o-------------------

R u t h B ooker, An Infant, By Dovie Booker, Her Mother

And Next Friend, N e l l ie P eo ples , An Infant, By Manie

Peoples, Her Mother And Next Friend, H ardest

K n o w les V an H ook, An Infant, By Mardest Harris,

Her Mother And Next Friend, And E l ij a h N o el , J o seph

M cG h e e , J r .,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

S tate oe T e n n e sse e B oard of E d ucation , Q u il l E . C o pe ,

S tate C o m m issio n er of E ducation and C h a ir m a n S tate

B oard of E d ucation , E r n e st C. H all , N orm an F rost,

E dward L . J e n n in g s , W . R . L a n d r u m , C h e st e r P ar

h a m , F erdinand P o w ell , R obert P . W il l ia m s , J. H oward

W ard, S am W il so n , M em bers of t h e S tate B oard of

E ducation of T e n n e s s e e , J. M . S m it h , P r esid en t1 of

M e m p h is S tate C ollege, R . P . Cla r k , R egistrar of

M e m p h is S tate C ollege,

Defendants-Appellees.

A ppe a l F rom t h e U n ited S tates D istrict Court for t h e

W estern D istrict of T e n n e s s e e , W estern D iv isio n

-------------------o-------------------

BRIEF FO R A PPELLANTS

Statem ent of Facts

Appellants are American citizens of Negro origin and

residents of Memphis, Tennessee. Each possesses all the

requisite qualifications for admission to Memphis State

College (See 82a-85a). Each was denied admission thereto

solely because of race and color. Appellants, thereupon,

2

brought this action in the court below seeking a declaratory

judgment vindicating their right to be admitted to the

College, and an injunction to restrain the enforcement of

Section 12, Article 11, of the Constitution of Tennessee

and Sections 11395, 11396 and 11397 of the Code of Ten

nessee on the ground that these constitutional and statu

tory provisions are in violation of the Constitution of the

United States. Jurisdiction of the court below was invoked

under Title 28, United States Code, Section 2281, as well as

under Sections 1331 and 1343 (3a-10a).

On June 21, 1955, appellees filed their answer alleging a

good faith attempt “ to comply with the decree of the

Supreme Court of the United States” by adopting a reso

lution providing for the transition from a segregated sys

tem to a nonsegregated system in all the state colleges,

institutions and normal schools in the following manner:

1. 1955-1956—Qualified Negro applicants to be admit

ted at the graduate level at Memphis State College,

Middle Tennessee State College, East Tennessee

State College and Austin Peay State College, and

qualified white students to be admitted to Tennessee

Agriculture and Industrial State University for

Negroes at Nashville.

2. 1956-1957—Qualified Negroes to be admitted to the

graduate and senior classes at the four institutions

named and to the Tennessee Polytechnic Institute at

Cooksville, and white students to be admitted to the

graduate and senior classes at Tennessee Agriculture

and Industrial State University for Negroes at

Nashville.

3. 1957-1958—Graduate, senior, junior and sophomore

classes at the above-named institutions will be opened

to all persons without regard to race or color.

3

4. 1959-60—Graduate, senior, junior’, sophomore and

freshman classes at the above-named institutions

will be opened to all persons without regard to race

or color.

This program was to be inoperative until state laws

declaring segregation had been held invalid in an appro

priate court action, and the decision of the United States

Supreme Court in the School Segregation Cases was held

applicable to state colleges and universities in the State

of Tennessee. (The text of this resolution is set out at

15a.)

Appellees contend that a policy of unrestricted admis

sion of Negroes to Memphis State College “ would over-tax

the physical facilities of the plant, ’ ’ basing this conclusion

on statistics showing the annual number of Negro and

white high school students graduating from Shelby County,

the county in which Memphis State College is located, and

supported their plan for gradual desegregation beginning

at the graduate level on the theory that the transition

would be easier if they admitted the more mature graduate

students before putting into practice a nondiscriminatory

policy involving younger students.

Appellants filed a motion for judgment on the plead

ings and, in the alternative, a motion for summary judg

ment on the ground that appellees had failed to state a

legal defense to appellants’ claim, and that there were no

genuine issues of fact between the parties (23a). Inter

rogatories were served on the appellees seeking to deter

mine the present total enrollment and that of the various

colleges and departments at Memphis State College and

the number of nonresident students enrolled in the college

(19a). In the answer to these interrogatories (21a, 22a)

it was disclosed that, in 1955, 143 out-of-state students and

1,079 non-residents of Memphis had been enrolled in the

college; that 50 out-of-state first year students and 30

4

out-of-state second year students were presently attend

ing the college.

A hearing was held in the court below on October 17,

1955. At the outset the court ruled that it had jurisdiction

to hear and determine the cause without the convening of

a three-judge court. (This appellants contend was error.)

The court further denied appellants’ motion for judgment

on the pleadings and, in the alternative, motion for summary

judgment and ordered a hearing on the merits. (This

appellants also contend was in error.)

As witness, the state called Dr. Quill Cope, Chair

man of the State Board of Education, who testified (24a-

52a) concerning the number of Negro and white high

school graduates from the counties from which Memphis

State College normally drew its student body; that

“ unbridled” integration would overtax the physical facili

ties at Memphis State College; that he didn’t know the

exact percentage of students from these counties who went

to state colleges rather than private colleges or institu

tions outside the state; that the school admitted out-of-state

students; that the only reason for the denial of admission

to these students was their race and color.

Dr. J. Millard Smith, the next witness for the appellees,

is the President of Memphis State College (53a-77a). He

testified concerning the need of the school to maintain

a certain student-teacher ratio in order to keep its accredita

tion; that if 27% of the Negro high school graduates of

Shelby County attended Memphis State College, it would

be over-crowded and, therefore, in danger of losing its

accreditation; that the institution admitted out-of-state

white students since appellants had applied for admission,

and the College wanted to continue this policy to avoid its

becoming a provincial school.

W. E. Turner, Coordinator of the Division of Instruc

tions of the Tennessee Department of Education and

5

Director of the Division of Negro Education, was the third

and final witness for the defense (77a-82a). He testified

concerning a questionnaire sent to approximately 35

principals of colored high schools in Western Tennessee.

Of this number he had received replies from 16 which

showed that out of some 674 graduates of Negro high schools

in that part of the state, 212 went to college.

(Appellants contend that all the testimony offered by

appellees was irrelevant and did not meet the issues raised

in their complaint.)

Appellees then orally stipulated that appellants, Mardest

Knowles Van Hook, Ruth H. Booker, Joseph McGhee, Jr.

and Nellie Peoples met the scholastic qualifications for

admission to Memphis State College (82a-84a), and appel

lant, Elijah J. Noel, testified concerning his scholastic

qualifications showing that he had graduated from a high

school in Marion, Arkansas, which was accredited, and

that he had done some college work at Howard University

in Washington, D. C., and at LeMoyne College in Memphis

(84a-85a). That he met the scholastic qualifications for

admission to Memphis State College was not challenged

by appellees.

The court then proceeded to dispose of this case on the

merits by ruling from the bench. The court ruled that

the appellees’ plan, which provided for the elimination of

segregation beginning in 1955-1956 at the graduate school

level and ending in 1959-60 with the opening of fresh

man classes to Negro applicants, constituted good faith

compliance with the requirements set forth by the Supreme

Court in its May 31, 1955 decision in the School Segre

gation Cases (Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S.

294); that the evidence disclosed that to order immediate de

segregation was not advisable and was impracticable and

that the plan which appellees had adopted was in the best

interest of all parties concerned (85a-89a).

6

On November 22, the court entered findings of fact and

conclusions of law which found that the Tennessee State

Board of Education was attempting to promptly comply

with the decision of the Supreme Court of the United

States and was not seeking to evade or circumvent that

decision; that the abrupt admission of Negro students

might endanger the accreditation of the school; that in

view of the fact that segregation had existed since 1870,

the gradual plan approved by the Board offered the

“ greater possibility of eventual complete acceptance of the

situation by members of both races than would an abrupt

transition at present. ’ ’

The court found that the appellees were proceeding

with all deliberate speed, and that the time provided by

the plan was absolutely necessary to carry out the decision

of the Supreme Court. The court struck down the con

stitutional and statutory provisions requiring segregation

in public schools and held that the invalidity of these laws

was fully evident and that the convening of a three-judge

court was not necessary for their enforcement to be en

joined as unconstitutional (91a-92a). The court found

that the plan devised by the Board was reasonable and

would lead to orderly and peaceful integration and directed

the Board to proceed to operate pursuant to the plan at once

(93a-94a).

The court entered a final decree denying the appellants ’

application for a permanent injunction. Appellants there

upon filed their notice of appeal on December 2, 1955. On

January 10, 1955, their cause was docketed in this Court.

7

ARGUM ENT

I

Did the court below have jurisdiction to hear and

determ ine this cause or was it a m atter which should

have been heard and determ ined by a three-judge

court pursuant to T itle 28, U nited States Code, Sec

tions 2281 and 2284.

T h e c o u r t b e lo w a n s w e rs th e q u e s tio n No.

A p p e lla n ts c o n te n d th e a n s w e r sh o u ld h a v e b e e n T es.

There is a conflict of authority on this question at the

present time, but appellants are of the opinion that a three-

judge court was required in this case. Title 28, United

States Code, Section 2281 requires the convening of a three-

judge court when an injunction is sought to restrain the

enforcement of a state policy on the ground of its unconsti

tutionality. The language of the statute is clear and unam

biguous and, if controlling, it is evident that in this case

the convening of a three-judge court is required.

This was the approach of the court in Frazier v. Board

of Trustees, 133 F. Supp. 589' (M. D. N. C. 1955) in holding

that a three-judge court had jurisdiction to enjoin the

Board of Trustees of the University of North Carolina

from refusing to admit Negroes to the University on the

grounds of race and color.

There can be little doubt, in view of the decision of the

Supreme Court of the United States in the School Segrega

tion Cases (Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483;

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497), that segregation in the

field of public education is invalid and that state statutes

requiring or seeking to enforce this policy are unconstitu

tional. On the other hand, some courts have taken the

view that since the law is so clear there is no need to con-

8

vene a three-judge court merely to determine what must

be determined in any event—that the state law is invalid.

This apparently was the approach in the instant case, in

Wells v. Walker, — F. Supp. — (W. D. Ky. 1955); Bell v.

Ripp, 133 F. Supp. 811 (N. D. Tex. 1955). And see Tureaud

v. Board of Supervisors, 116 F. Supp. 248 (E. D. La. 1953),

reversed, 207 F. 2d 807 (OA 5th 1953), vacated and re

manded, 347 U. S. 971, original judgment reinstated by the

district court and affirmed on appeal, 225 F. 2d 434, reversed

on rehearing, 226 F. 2d 714, judgment on rehearing vacated

and hearing ordered en banc, and the original judgment of

the Court of Appeals affirming the judgment of the lower

court reinstated, — F. 2d —, January 6, 1956.

Practical considerations would seem to favor this ap

proach. It certainly would seem to constitute an unwar

ranted burden on the federal judiciary and on the appel

late docket of the United States Supreme Court to require

the convening of a three-judge court in every case where

a Negro applicant seeks injunctive relief against the

enforcement of an obviously unconstitutional state statute

requiring segregation in education. Support for this view

is seemingly based upon the established right of a single

judge to dismiss a complaint seeking to enjoin the enforce

ment of a state law when no substantial question of consti

tutionality is involved. See United Drug Co. v. Graves, 34

F. 2d 808 (M. D. Ala., 1929); Chapman v. Boynton, 4 F.

Supp. 43 (D. C. Kans. 1933); Norumbega Co. v. Bennett,

290 U. S. 598. These cases appear to be at odds with Ex

Parte Metropolitan Water Co., 220 U. S. 539, which has

never been overruled or modified, in which the Supreme

Court held that a single judge, to whom application for

an interlocutory injunction was presented, had no authority

to pass upon that application without the assistance of

two other judges, even though he was of the opinion that

the claim of unconstitutionality was untenable.

9

The apparent contradiction between Norumbega, United

Drug Co., Chapman and Metropolitan Water Co. was ap

parently reconciled by the Supreme Court in Ex Parte

Poresky, 290 U. S. 30. In that case the language would

seem to indicate that the sanctioning of a dismissal by a

single judge in an action, where an application for injunc

tive relief is made, is no authority to sustain the jurisdic

tion of a single judge to enter an injunction, where the

unconstitutionality of a statute is free of doubt. But com

pare Tureaud v. Board of Supervisors, supra. In Poresky,

the Supreme Court held that before a federal judge under

takes to proceed in a case, he must first ascertain whether

he has jurisdiction, and if no substantial federal question

is present, requisite federal jurisdiction is lacking, and he is

required to dismiss the complaint. It does not follow, how

ever, that because a single judge has authority sitting alone

to dismiss, where no substantial federal question exists, that

he also has authority to enjoin the enforcement of a state’s

policy, even where the unconstitutionality of that policy is

free of doubt.

Admittedly it is difficult to differentiate between a ruling

on the merits and a ruling on jurisdiction for the two are

perhaps inextricably entwined. See Johnson and Wash

ington, “ One or Three—Which Shall It Be?” 1 How. L.

Rev. 194, 218 (1955), but nonetheless this is the stated

ground on which the earlier cases rested. There is some

support for the view that the legislative history of the 1942

amendment to Section 2284 was intended to overrule even

the exception made in the Poresky case. See Hart and

Wechsler, “ The Federal Courts and the Federal System,”

852 (1953), but that exception has been recently affirmed in

Robinette v. Campbell, 342 TJ. S. 940. The district court

dismissed the complaint following the theory in Ex Parte

Poresky, 115 F. Supp. 699 (N. D. 111. 1951) and the motion

for leave to file a petition for writ of mandamus was

denied.

10

It should be pointed out that arguments of policy and

of legislative history are relevant in construing a statute

only when there is ambiguity in the legislative language

which must be resolved, Unexcelled Chemical Co. v. United

States, 345 U. S. 59. Where the meaning of a statute is

not clear on its face, the purpose of Congress is a dominant

factor in determining its meaning. See United States v.

Congress of Industrial Organizations, 335 U. S. 106; United

States v. Universal C.I.T. Credit Corp., 334 U. S. 218, 221,

222, where Mr. Justice Frankfurter speaking for the Court

said:

We may utilize, in construing a statute not unam

biguous, all the light relevantly shed upon the words

and the clause and the statute that express the pur

pose of Congress.

# * #

Instead of balancing the various generalized

axioms of experience in construing legislation, regard

for the specific history of the legislative process that

culminated in the Act . . . affords more solid ground

for giving it appropriate meaning.

Here, despite the heavy burden which the convening of

a three-judge court undoubtedly places upon the federal

judiciary, the language of the statute is clear that where

injunctive relief is sought against the enforcement of a

state statute on the grounds of its unconstitutionality that

a three-judge court must be convened. Hence, the propriety

of the court below in striking down the statute of Tennessee

on the ground of unconstitutionality is not free from doubt.

Moreover, the procedural uncertainty which may beset an

applicant seeking admission to a state school from which

he has been barred by state law, when a judge does not

follow the mandate of Sections 2281 and 2284 (see Tureaud

case, supra), makes it mandatory that the statute’s language

be followed until an authoritative pronouncement by the

Supreme Court of the United States resolves the question.

11

1 or these reasons, we submit that the court below was

incorrect in proceeding to dispose of this case on the merits

without first convening a three-judge court. While we

recognize that this Court cannot deal with the question with

finality, we raise it here since it must be disposed of first

before this Court disposes of this appeal on its merits.

I I

A re appellants en titled to an order requiring their

im m ediate adm ission to M emphis S tate College?

T h e c o u r t b e lo w a n s w e re d th e q u e s tio n No.

A p p e lla n ts c o n te n d th e a n s w e r sh o u ld h a v e b e e n F es .

Appellants are entitled to an order requiring their im

mediate admission to Memphis State College. The right

to equal educational opportunities is personal and present.

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 641; Sweatt v. Painter,

339 U. S. 629; McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339

IT. S. 637.

This is a simple case of qualified Negro applicants

seeking to attend a state college formerly restricted to

white persons solely on the basis of race and color. No

complicated legal or administrative factors are present

with winch the University officials have to deal in order

to vindicate the rights of these applicants. Such right

to immediate admission at the higher educational level

has been upheld consistently, even at the time when courts

considered the “ separate hut equal” doctrine governed

disposition of the cases. McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F.

2d 949 (CA 4th 1951), cert, denied, 341 U. S. 591; Wilson

v. Board, of Supervisors, 92 F. Supp. 986 (E. D. La. 1950),

aff’d, 340 U. S. 906; Parker v. University of Delaware, 75

A. 2d 225 (Del. 1950); Wichita Falls Junior College Dis

trict v. Battle, 204 F. 2d 632 (CA 5th 1953), cert, denied,

12

347 U. S. 974; Wilson v. City of Paducah, 100 F. Supp. 116

(W. D. Ky. 1951); Mitchell v. Board of Regents of the Uni

versity' of Maryland, Docket No. 16, Folio 126 (Baltimore

City Court 1950) unreported; Swanson v. University of

Virginia, Civil Action 30 (W. D. Va. 1950) unreported;

and see Gray v. Board of Trustees of University of Ten

nessee, 342 IT. S. 517.

Since the decision of the Supreme Court in the School

Segregation Cases this approach has been followed in the

overwhelming majority of cases. See Lucy v. Adams,

— U. S. —, Oct. 10, 1955; Frazier v. Board of Trustees,

supra; Tureaud v. Board of Supervisors, supra; Wells

v. Dyson, Civil Action No. 4679 (E. D. La. decided Apr. 2,

1955) unreported; White v. Smith, Civil Action No. 1616

(W. D. Texas, decided July 28, 1955) unreported; Grant v.

Taylor, Civil Action, No. 6404 (W. D. Okla. 1955) un

reported; Whitmore v. Stillwell, — F. 2d — (CA 5th de

cided Nov. 3, 1955); Troullier v. Proctor, Civil Action No.

3842 (E. D. Okla. 1955) unreported.

Only in this case and in State of Florida ex rel Hawkins

v. Board of Control, 80 So. 2d 20' (1955), has there been a

departure from the granting of immediate relief. Reduced

to its bare essentials, the decision below means that a Negro

seeking equal education opportunities at the higher educa

tion level is now in a more adverse position since the decision

in the School Segregation Cases than he was when the

“ separate but equal” doctrine was considered controlling.

This, we respectfully submit, could not have been the in

tention of the Supreme Court of the United States.

The court below relied upon the decision of the Supreme

Court in Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294, in

which the formula for the granting of relief at the public

school level was laid down. We submit that the formula

has no relation to the instant case. In that case the court

was dealing with questions of the reorganization of

13

an entire public school system in which school authorities

had to concern themselves with redistricting of schools,

with reassignment of teachers, with reassignment of pupils

on a mass basis in order to make the transition from a

system of segregation to one free of racial discrimination.

In that instance the Court indicated that the school authori

ties might have to consider problems “ related to adminis

tration, arising from the physical condition of the school

plant, the school transportation system, personnel, revi

sion of school districts and attendance areas into compact

units to achieve a system of determining admission to

the public schools on a nonraeial basis and revision of local

laws and regulations which may be necessary in solving the

foregoing problems. ’ ’

The Court further indicated that courts had authority

to “ consider the adequacy of any plan” the school officials

may propose “ to meet these problems and to effect a

transition to a racially nondiscriminatory school system.”

Fo such factors are present and no such problems are in

the instant case. All the testimony in support of the

appellees’ plan relate to abstract hypotheses which would

render difficult the admission of Negroes to the Memphis

State College. There was no showing that, in fact, a large

number of Negroes would apply to Memphis State College

and, therefore, unduly burden the physical facilities of

the plant.

The school admits out-of-state white students, and the

interrogatories disclosed that at the present time fifty

out-of-state white first year students are enrolled at the

college and thirty out-of-state white second year students

are enrolled in the college, and that in 1955 a total of

143 out-of-state white students had been enrolled in the

college.

While this is a class action, and a ruling by the court,

that the state policy of excluding persons from the college

u

solely on the basis of race is unconstitutional, would require

it to no longer consider race in determining whether to

admit students in the future, this does not necessarily

mean that school as the testimony seeks to indicate, would

be under obligation to open its doors for the “ unbridled”

admission of all students. Clearly the state would have

to and could lay clown standards and establish criteria for

admission which would keep it from overtaxing its facilities

and enable it to maintain its accreditation. The removal of

its discriminatory policy is not the factor which would

imperil its standing as an accredited institution. In fact,

the plan which the defendants have adopted and which

the court below approved completely denies to these appli

cants their constitutional right to enter the school. Under

the plan approved below, they would be unable to enter

Memphis State College until 1959-60, and, we submit, that

it was error, and an abuse of discrimination on the part of

the court below to approve and adopt appellees’ plan.

Relief

Under the foregoing circumstances, it is respectfully

submitted, that appellants are entitled to an order requir

ing their admission to Memphis State College, subject

only to the same rules and regulations applicable to all

other students without delay, and that a postponement

of their relief pursuant to the plan adopted by the State

Board of Education constitutes, in effect, a complete denial

of their constitutional rights.

15

CONCLUSION

W herefore, for the reasons hereinabove stated, it

is respectfully subm itted the judgm ent of the court

below should be reversed.

H. T. L ockard,

322% Beale Avenue,

Memphis, Tennessee,

R obert L . Carter ,

T htjrgood M arsh a ll ,

107 West 43rd Street,

New York, New York,

Counsel for Appellants.

J. F. E stes,

B . L . H ooks,

A. W. W illis , J r.,

Z. A lexander L ooby,

of Counsel.

I