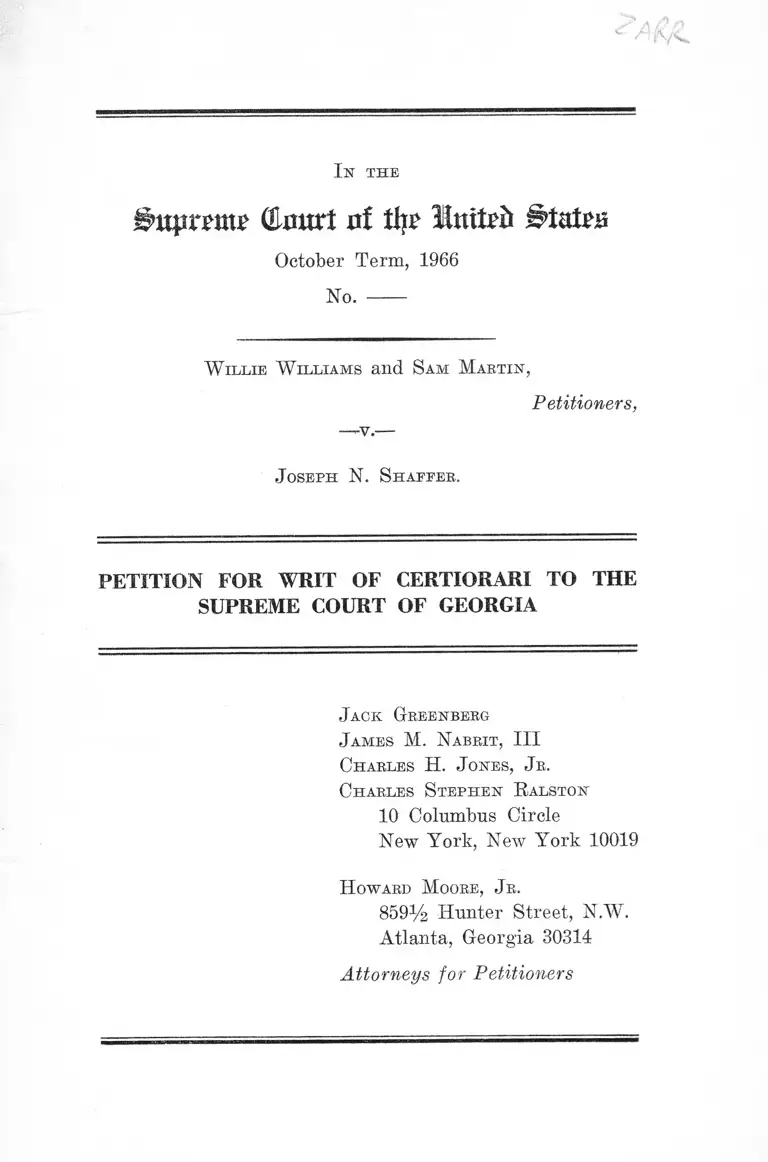

WIlliams v. Shaffer Petition for Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 3, 1966

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. WIlliams v. Shaffer Petition for Writ of Certiorari, 1966. cd253d54-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/558a4574-44e0-4330-934a-9f0c00df4a2e/williams-v-shaffer-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

1st th e

(Hmtrt uf % Blmfrii

October Term, 1966

No. ------

W illie W illiams and Sam Martin,

Petitioners,

J oseph N. Shaffer.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Charles H. J ones, Jr.

Charles Stephen R alston

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

H oward Moore, J r.

859% Hunter Street, NW.

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

PAGE

Citations to Opinions Below ........ ................-...............

Jurisdiction .......................................................................

Questions Presented..........................................................

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved.......

Statement ...........................................................................

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided

B elow ...............................................................................

R easons eor Granting the W rit :—

The Court Should Grant Certiorari To Consider

Petitioners’ Contentions That Georgia Code

§ 61-303, Which Barred Them From A Hearing

Because Of Their Poverty, Is In Conflict With

Principles Declared By This Court And Is Un

constitutional Under The Equal Protection And

Due Process Clauses Of The Fourteenth Amend

ment ............................................................................

Certiorari Should Be Granted to Decide the Ques

tions Presented Since the Court Below Erred in

Its Determination That Petitioners’ Cases Have

Become Moot ................ ...........................................

The Question of the Right of an Indigent Tenant

to Remain in Possession and Defend Against Evic

tion Without Posting Substantial Security Re

quired By a State Statute Is of General Im

portance - ...................................................................

Conclusion.................................................................................

A ppendix .....................................................................................

1

2

2

3

5

8

10

16

21

24

la

11

T able oe Cases

Albany v. White, 46 Misc. 2d 915, 261 Misc. Supp. 2d

361 (1965) ..................................................................... 18

Burns v. Ohio, 360 U.S. 252 ............................................. 12

Cochran v. Kansas, 316 U.S. 255 ................................. 13

DeFlorio v. Tarvin, 193 Ga. 760, 20 S.E.2d 29 ........... 13

Dowd v. Cook, 340 U.S. 206 ............................................. 13

Edwards v. California, 314 U.S. 160 ............................. 12

Flynn v. Merck,------Ga.----- - , 49 S.E.2d 892 (1948) .... 13

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 ............................. 12

Goshen Mfg. Co. v. Hubert A. Myers Mfg. Co., 242

U.S. 202 :..................................... .................................... 21

Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 ................................. 10,14,15

Harper v. Yirgina State Board of Elections, 383

U.S. 663 ....................... ..................................................12,14

Hovey v. Elliott, 167 U.S. 409 .....................................10,13

Jones v. Gammon, 123 Ga. 47, 50 S.E. 982 .................. 18

Lehmann v. West Seventy-Sixth St. Man. Corp., 67

N.Y.S.2d 91 (Sup. Ct. N.Y.C. 1946) .......................... 18

Liner v. Jafco, 375 U.S. 301 ............................................. 16

Love v. Griffith, 266 U.S. 3 2 ............................................. 16

Marluted Realtjr Corp. v. Decker, 260 N.Y. Supp. 2d

988 ................ ......................................

Murdock v. Pennsylvania, 319 U.S. 105

PAGE

18

12

Ill

Napier v. Varner, 149 Ga. 586, 101 S.E.2d 2 9 .............. 13

National Union of Marine Cooks v. Arnold, 348 U.S. 37 13

Porter v. Lee, 328 U.S. 246 .........................................17,18

Skoals Power Co. v. Fortson, 138 Ga. 460, 75 S.E. 606 18

Sistrunk v. State of Georgia, 18 Ga. App. 42, 88 S.E.

796 ................................................................................... 15

Smith v. Bennett, 365 U.S. 708 ................................. ....... 12

Southern Pacific Terminal Co. v. Interstate Commerce

Commission, 219 U.S. 491.......................................... 20

PAGE

Texas & N. O. R. Co. v. Northside Belt R. Co., 276

U.S. 475 ........ 17

United States v. Trans-Missouri Freight Ass’n, 166

U.S. 290 ................................................................18,19,20

Walling v. Helmerich & Payne, Inc., 323 U.S. 37 ....... 20

Ward v. Love County, 253 U.S. 1 7 ................................. 16

Willie Williams and Sam Martin v. T. Ralph Grimes

and Joseph N. Shaffer, Civil Action No. 10,025 (Slip

op. 1166, M.D. Ga.) ......................................................9,17

Windsor v. McVeigh, 93 U.S. 274 .............................11,12

Worthy v. Tate, 44 Ga. 152 ............................................ 13

F edebal Statutes and R ules

U. S. Constitution, Amendment XIV, Sec. 1 ...........3, 8, 9

28 U.S.C. §1257(3) ........................................................ 2

28 U.S.C. § 1446 .............................................................. 15

29 U.S.C. §407 ................................................................ 15

31 U.S.C. § 518 ................................................................ 15

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure 65 .......................... 15

IV

Georgia Statutes page

Georgia Code Ann., Title 24, § 3413 ............................ 24

Georgia Code Ann., Title 26, §§ 4001-4002 ................... 15

Georgia Code Ann., Title 37, § 1403 ............................ 15

Georgia Code Ann., Title 39, §§ 301-302 ....................... 15

Georgia Code Ann., Title 61, § 301 .......................... 3, 5

Georgia Code Ann., Title 61, § 302 ................. ............ 3, 5

Georgia Code Ann., Title 61, § 303 .........4, 5, 6, 8, 9,15, 21

Georgia Code Ann., Title 61, § 304 ........................4, 5, 6, 7

Georgia Code Ann., Title 61, § 305 ............................. 4, 6

Georgia Code Ann., Title 88, § 702 .............................. 15

Georgia Code Ann., Title 88, § 801 ............. 15

Other State Statutes

Arkansas Statutes Annotated (1947), Title 34, § 1510 .. 23

California Code of Civil Procedure, § 1166a .............. 23

Burns Indiana Statutes Annotated (1933), §§3-1304

through 3-1306 ........................................................ 23

Mississippi Code Annotated (1942), Title 7, §957 ....... 23

Texas Buies of Civil Procedure (1955), Buie 740 ....... 23

Virginia Code Annotated (1950), Title 55, § 242 ........... 23

Bevised Code of Washington (1961), §59.12.100 .......23,24

West Virginia Code (1961), § 3672 ................................. 24

V

Other A uthorities page

Diamond, Federal Jurisdiction To Decide Moot Cases,

94 U.Pa.L.Rev. 125 (1946) ......................................... 18

Millspaugh, Problems and Opportunities of Relocation,

26 Law and Contemporary Problems 6 (1961) ........... 22

Note, Cases Moot On Appeal: A Limit On The Judicial

Power, 103 U.Pa.L.Rev. 772 (1955) .......................... 18

Note, The Enforcement of Municipal Housing Codes,

78 Harvard Law Review 801 (1965) .......................... 23

Schier, Carl, Protecting the Interests of the Indigent

Tenant: Two Approaches, 54 California Law Re

view 670 (1966) ............................................................ 22

Schorr, Alvin L., Slums and Social Insecurity (U.S.

Government Printing Office, 1963) ..........................22, 23

Sehoshinsld, Robert S., Remedies of the Indigent

Tenant: Proposal for Change, 54 Georgetown Law

Journal 519 (1966) ........................................................ 23

"Wald, Patricia M., Law and Poverty: 1965 , (Wash

ington, D. C.: 1965) .................................................... 23

In the

Supreme (Hmtrt at tty Ittilrft States

October Term, 1966

No. ------

W illie W illiams and Sam M artin ,

— ■v .—

Petitioners,

J oseph N. Shappee.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgments of the Supreme Court of Georgia entered

in the above entitled cases June 23, 1966, infra, p. 7a, re

hearing denied July 7, 1966, infra, p. 8a. A single petition

is filed in the two cases pursuant to this Court’s Rule 23(5),

since the cases were consolidated for decision by the court

below.

Citations to Opinions Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Georgia is reported

at 149 S.E. 2d 668 (1966), and is printed in the Appendix

hereto, infra, pp. 3a-6a. The Superior Court of Pulton

County, Georgia, did not deliver an opinion in the cases.

Its orders are printed in the Appendix hereto, infra, pp.

la-2a.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgments of the Supreme Court of Georgia were

entered June 23, 1966, infra, p. 7a. Motions for rehearing

were denied by the Supreme Court of Georgia July 7, 1966,

infra, p. 8a. The time for filing this petition for writ of

certiorari was extended to and including December 3, 1966

by an order signed by Mr. Justice Black on September 28,

1966.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked under 28 U.S.C.

§ 1257(3), petitioners having asserted below and asserting

here deprivation of rights secured by the Constitution of

the United States.

Questions Presented

Petitioners, both indigent Negroes, formerly residing in

low rental apartments in Atlanta, Georgia, were summarily

evicted pursuant to procedures established by Georgia

Code Title 61, §§301-305. Because the statute requires the

posting of a bond with substantial security as a pre-condi

tion to making any defense, they were denied a hearing

on defenses they attempted to assert:

1. Under these circumstances were petitioners denied

rights guaranteed by the equal protection and due process

clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States

Constitution1?

2. Are their cases moot because of the evictions, in

view of the facts that: (a) the evictions were able to be

carried out solely because of the unconstitutional proce

dure; (b) their rights will be affected by any decision

upon the constitutionality of the statutes; and (c) there

is a substantial public interest in the continued unconstitu

tional operation of the statutes!

3

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

This case also involves the summary eviction procedure

provided by the statutes of the State of Georgia:

Georgia Code Annotated, Vol. 19

Title 61

61-301. Demand for possession; proceedings on ten

ant’s refusal to deliver.—In all cases where a tenant

shall hold possession of lands or tenements over and

beyond the term for which the same were rented or

leased to him, or shall fail to pay the rent when the

same shall become due, and in all cases where lands

or tenements shall be held and occupied by any tenant

at will or sufferance, whether under contract of rent

or not, and the owner of the lands or tenements shall

desire possession of the same, such owner may, by

himself, his agent, attorney in fact or attorney at law,

demand the possession of the property so rented,

leased, held, or occupied; and if the tenant shall re

fuse or omit to deliver possession when so demanded,

the owner, his agent or attorney at law or attorney

in fact may go before the judge of the superior court

or any justice of the peace and make oath to the facts.

(p. 106)

61-302. Warrant for tenant’s removal.—When the

affidavit provided for in the preceding section shall be

made, the officer before whom it was made shall grant

and issue a warrant or process directed to the sheriff,

or his deputy, or any lawful constable of the county

where the land lies, commanding arid requiring him

to deliver to the owner or his representative full and

4

quiet possession of the lands or tenements mentioned

in the affidavit, removing the tenant, with his property

found thereon, away from the premises, (p. 124)

61-303. Arrest of proceedings by tenant; counter

affidavit and bond.—The tenant may arrest the pro

ceedings and prevent the removal of himself and his

goods from the land by declaring on oath that his

lease or term of rent has not expired, and that he is

not holding possession of the premises over and be

yond his term, or that the rent claimed is not due, or

that he does not hold the premises, either by lease, or

rent, or at will, or by sufferance, or otherwise, from

the person who made the affidavit on which the war

rant issued, or from anyone under whom he claims

the premises, or from anyone claiming the premises

under him : Provided, such tenant shall at the same

time tender a bond with good security, payable to the

landlord, for the payment of such sum, with costs, as

may be recovered against him on the trial of the case,

(pp. 124-125)

61-304. Issue tried in superior court.—If the counter

affidavit and bond provided in the preceding section

shall be made and delivered to the sheriff or deputy

sheriff or constable, the tenant shall not be removed;

hut the officer shall return the proceedings to the next

superior court of the county where the land lies, and

the fact in issue shall be there tried by a jury. (p. 129)

61-305. Double rent and writ of possession, when.—

If the issue specified in the preceding section shall be

determined against the tenant, judgment shall go

against him for double the rent reserved or stipulated

to be paid, or if he shall be a tenant at will or suffer

ance, for double what the rent of the premises is

5

shown to be worth, and such judgment in any case

shall also provide for the payment of future double

rent until the tenant surrenders possession of the

lands or tenements to the landlord after an appeal or

otherwise; and the movant or plaintiff shall have a

writ of possession, and shall be by the sheriff, deputy,

or constable placed in full possession of the premises,

(p. 135)

Statement

Petitioner Willie Williams was renting several rooms

from defendant Joseph Shaffer at 424 Markham Street in

Atlanta, Georgia (R-W 6).1 Petitioner Sam Martin was

renting a single room from the same landlord at 445 Miller

Alley S.W. in Atlanta, Georgia (R-M 6).2

Acting under procedures established by Georgia Code

Title 61, §§ 301-302, defendant landlord on or about Febru

ary 22, 1966 procured dispossessory warrants from a judge

of the Fulton County Superior Court directed to the county

sheriff to dispossess each petitioner (R-W 6,14; R-M 6, 14).

Following notification of the existence of the disposses

sory warrant, each petitioner attempted to arrest the evic

tion proceedings and prevent his removal from the prem

ises under procedure established by Georgia Code Title 61,

§§ 303-304. Each sought to file an appropriate counter-affi

davit in the Superior Court of Fulton County raising de

fenses together with an affidavit that he was unable to post

1 There were originally two cases, but they were consolidated for deci

sion by the Supreme Court of Georgia since the relevant facts and issues

are identical. The citation “R -W ” is to the record in Willie Williams v.

Joseph N. Shaffer, and the citation “R-M” is to the record in Sam Martin

v. Joseph N. Shaffer.

2 See footnote 1.

6

security as required by that statute in such cases due to his

poverty (R-W 5-24; R-M 5-23).

The nature of the defenses which each petitioner sought

to raise to the eviction proceeding included (1) that the

rent claimed was not due (R-W 9; R-M 9); (2) that he was

willing and able to pay all further rents as they became

due (R-W 9; R-M 8-9); (3) pursuant to an agreement be

tween himself and the defendant landlord, petitioner had

made certain repairs on the premises for which materials

and labor the defendant landlord was to credit against

rents due or to become due (R-W 7-8; R-M 7-8); (4) de

fendant landlord had failed to give the petitioner the

notice required by law of his intention to terminate the

tenancy (R-W 7; R-M 7); (5) two weeks previously de

fendant landlord procured a dispossessory warrant for

the same premises, and upon subsequent appearance in the

Fulton County Civil Court, defendant landlord volun

tarily announced that he had received his rent and that he

accepted petitioner as a tenant in the premises (R-W 6-7;

R-M 6-7); (6) that the defendant landlord was abusing the

process of the Court to avoid making the necessary repairs

required of him by law on the premises in issue, and to

avoid compensating petitioner for making repairs (R-W 8;

R-M 8).

The security required by Title 61, § 303 is substantial.

Georgia Code Title 61, § 305 provides that if the issue is

determined against the tenant, judgment shall go against

him for double the rent due for the period during which

he was in possession after the initial attempt at eviction,

and Title 61, § 304 provides that the issue shall be tried

in Superior Court before a jury—a procedure which may

require several months (R-W 17-18; R-M 18-19). The

Marshal of the Civil Court of Fulton County, who is

charged with the duty of accepting the bond and staying

7

the eviction proceedings by Title 61, § 304, stated that

he would accept only surety on bonds furnished by a li

censed corporate surety, or an individual surety who owns

real property located in Fulton County sufficient in value

to support the bond involved (R-W 18; R-M 17). The

several insurance agencies contacted, which were known

to post dispossessory bonds for tenants, advised that it

would be necessary for each petitioner to put up a cash

collateral for double the rent for about six months, as

well as pay an unrecoverable bond premium (R-W 16;

R-M 17).

The circumstances of petitioner Willie William’s poverty,

which supported his affidavit of inability to post the secur

ity, was that he was presently unemployed; when last em

ployed as a handy man he earned $50 a week; the rent in

issue was $17 a week; he had a wife and three children

who lived with him at the premises in issue; he had to

spend about $9 a week for wood and coal to heat the prem

ises (R-W" 8-9). The circumstances of petitioner Sam

Martin’s poverty, which supported his affidavit of inability

to post the security, was that he earned $54 a week in

construction work; the rent in issue was $6 a week; he

had to spend about $3 a week for coal to heat the premises

in issue; the premises were in such dilapidated condition

that he had to make continuous expenditures to keep them

habitable (R-M 15-16). Both petitioners were without

friends or relatives able to post security in the form of

real property located in Fulton County for the bond re

quired (R-W 10; R-M 11).

8

How the Federal Questions Were Raised

and Decided Below

In their petitions to the Superior Court of Fulton County

attempting to arrest the eviction proceedings, each peti

tioner sought vacation of the dispossessory warrants of

February 22, 1966, and injunctions against the defendant-

landlord and the sheriff of Fulton County restraining them

from executing said dispossessory warrants, on the ground

that Georgia Code Title 61, § 303 violates the equal pro

tection and due process clauses of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the United States Constitution, in that said statute

invidiously barred petitioners from obtaining hearings in

the courts of the State of Georgia of any defenses which

they might have to said evictions solely because of their

poverty (R-W 9-12; R-M 9-12). Each petitioner sought

to be allowed to pay into the registry of the Superior

Court any rents due or to become due to the defendant-

landlord during the pendency of the action, requested that

the defendant-landlord be enjoined from evicting peti

tioners until the disposition of the case, and sought such

other and further relief as might appear just during the

course of the proceedings (R-W 12; R-M 12).

After oral argument in the Superior Court of Fulton

County, both the petition of Willie Williams and the peti

tion of Sam Martin for injunctions were denied, and de

fendant-landlord Joe Shaffer’s motions to dismiss were

granted, in orders of March 2, 1966 (R-W 25; R-M 24).

Each petitioner appealed to the Supreme Court of

Georgia from the above orders and judgments (R-W 1;

R-M l ) .3 In the Enumeration of Errors, each petitioner

_ 3 Following the denial of the injunction in the state court, both peti

tioners also filed a consolidated suit in the United States District Court

9

again asserted that Georgia Code Title 61, § 303, requiring

the posting of a bond as a condition precedent to the

making of a defense by a tenant in a dispossessory pro

ceeding, constituted a violation of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States (R-W 28-29;

R-M 27-28). The Attorney General of Georgia filed a brief

in the Supreme Court on behalf of the State of Georgia,

and the Atlanta Real Estate Board filed an amicus curiae

brief.

The Supreme Court of Georgia, in a single consolidated

decision of the two cases on June 23, 1966, dismissed the

appeals on the ground that since the court below had re

fused to stay the dispossessory proceedings pending ap

peal, the sheriff of Fulton County had, in fact, evicted the

petitioners from their respective premises on March 5,

1966, thereby rendering the cases moot, since all that was

sought to be enjoined had been done. The Court also re

fused to consider the cases as seeking declaratory judg

ments since there were no circumstances alleged which

showed that an adjudication of petitioners’ rights was

necessary in order to relieve them from the risk of taking

for the Northern District of Georgia, Atlanta Division ( Willie Williams

and Sam Martin v. T. Ralph Grimes and Joseph N. Shaffer, Civil Action

No. 10,025), asking for a restraining order against the Sheriff o f Fulton

County and defendant landlord from evicting petitioners under the state

proceedings, a permanent injunction against the enforcement of Title 61,

§ 303, and a declaratory judgment rendering such section null and void.

A three-judge court was impaneled. The State of Georgia through the

Attorney-General intervened as a matter of right, and the Atlanta Real

Estate Board also intervened as amicus curiae. The district court denied

relief in an opinion dated April 18, 1966, on the ground that a state

proceeding was still in progress and that there was a possibility of

obtaining relief therein.

Subsequent to the denial of relief by the Supreme Court of Georgia,

petitioners filed a motion for reconsideration in the district court. This

was denied in an order dated August 23, 1966 and the original opinion

was re-adopted.

10

any future action incident to their rights, which action

without direction would jeopardize their interests (R-W

33-41; R-S 32-40) (R-W 33-41; R-M 32-40). The Supreme

Court of Georgia did not make any explicit determination

concerning petitioners’ Constitutional claims.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

The Court Should Grant Certiorari To Consider

Petitioners’ Contentions That Georgia Code § 61-303,

Which Barred Them From A Hearing Because Of

Their Poverty, Is In Conflict With Principles Declared

By This Court And Is Unconstitutional Under The

Equal Protection And Due Process Clauses O f The

Fourteenth Amendment.

The decision of the court below is in conflict with deci

sions of this Court as exemplified by Ilovey v. Elliott, 167

U.S. 409 and Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12. Sections 303-304

of Title 61 of the Georgia Code Annotated require that

any defendant in a summary ejectment action post a bond

with good security as a precondition to making any de

fense. An indigent defendant may be divested summarily

of valuable rights solely because of his poverty without

regard to the merits. Petitioners submit that this require

ment violates the due process and equal protection clauses

of the Fourteenth Amendment when applied to an indigent

tenant-defendant.

This Court has long made clear that a state government

violates due process of law by subjecting defendants in civil

or criminal proceedings to judicial processes which deny

such fundamental rights as to notice and opportunity to

appear and defend. Hovey v. Elliott, 167 U.S. 409, decided

11

in 1897, held that due process was denied by a trial court

which struck a defendant’s answer and refused to permit

him to try his case on the merits because he had disobeyed

the court’s order to pay into its registry money which was

the subject matter of the controversy. The Court reasoned

that the denial of all right to defend would convert the

court into an instrument of wrong and oppression.

In Windsor v. McVeigh, 93 U.S. 274, although notice was

given in a proceeding to confiscate property under a Civil

War statute, petitioner’s answer was stricken and judg

ment was summarily rendered against him. Mr. Justice

Field, in a decision reversing the lower court, described

why the due process clause requires that a defendant be

afforded an opportunity to appear and defend:

Wherever one is assailed in his person or his property,

there he may defend, for the liability and the right are

inseparable. This is a principle of natural justice,

recognized as such by the common intelligence and

conscience of all nations. A sentence of a court pro

nounced against a party without hearing him, or giving

him an opportunity to be heard, is not a judicial deter

mination of his rights, and is not entitled to respect

in any other tribunal.

That there must be notice to a party of some kind,

actual or constructive, to a valid judgment affecting

his rights, is admitted. Until notice is given, the court

has no jurisdiction in any case to proceed to judgment,

whatever its authority may be, by the law of its organi

zation, over the subject matter. But notice is only for

the purpose of affording the party an opportunity

of being heard upon the claim of the charges made;

it is a summons to him to appear and speak, if he has

anything to say why the judgment sought should not

12

be rendered. A denial to a party, of the benefit of a

notice would be in effect to deny that he is entitled to

notice at all, and the sham and deceptive proceeding

had better be omitted altogether. It would be like

saying to a party: appear, and you shall be heard; and,

when he has appeared, saying: your appearance shall

not be recognized, and you shall not be heard. 93 IT.S.

at 277, 278.

Thus, just as the exercise of such basic rights as free

speech,4 the right to travel from one state to another,5 the

right to vote6 or the right to counsel7 cannot be conditioned

on affluence, neither may the right to defend in a civil

action before valuable property rights are taken away.

Similarly, this Court has held that to condition on one’s

affluence the undertaking of certain proceedings violates the

equal protection clause. The Court has struck down fee limi

tations on the right of criminal defendants to take an appeal,

Burns v. Ohio, 360 U.S. 252, or to file a petition for a writ

of habeas corpus, Smith v. Bennett, 365 U.S. 708. To re

quire an indigent to pay such fees was invalid, since

“ [t]here is no rational basis for assuming that indigent’s

motions for leave to appeal will be less meritorious than

those of other defendants,” Burns v. Ohio, supra, at 257,

258.8 Nor can the state, acting through penal institutions,

impose rules which make arbitrary distinctions between

4 Murdoch v. Pennsylvania, 319 U.S. 105.

5 Edwards v. California, 314 U.S. 160.

6 Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections, 383 U.S. 663.

7 Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335.

8 In contrast, the federal in forma pauperis statute, 28 U.S.C. § 1915,

permits a federal court to deny leave to appeal in forma pauperis but

only after a finding, reviewable on appeal, that the appeal is without

merit and not in good faith.

13

those who can and who cannot appeal. See Cochran v. Kan

sas, 316 U.S. 255; Dowd v. Cook, 340 U.S. 206.9

In determining both whether the Georgia statute vio

lates due process and whether it denies equal protection of

the laws, the determining factor is whether there is any

rational or legitimate basis for imposing a fee requirement

that distinguishes between tenant-defendants with and with

out means to furnish bonds before having their defenses

heard. Petitioners contend that there is no such justifica

tion, but that on the contrary the state has created an

irrational distinction between the affluent and the indigent

tenant, raising, in effect, an irrebuttable presumption that

the defenses of the indigent tenant are without merit.10

However, since there is no rational basis for presuming

that the defense of the indigent tenant is less meritorious

than that of affluent tenant-defendants, the state has

created an “ invidious discrimination” against the poor

by making affluence a standard of measurement as to which

9 A distinction has been drawn between a state fee requirement on

taking an appeal, as applied to an indigent, and a requirement o f post

ing a bond on appeal as security. National Union of Marine Cooks v.

Arnold, 348 U.S. 37. But the Court in Arnold expressly distinguished

between a bond requirement on appeal from such a requirement as a pre

condition to making a defense at trial, on the ground that at the appellate

stage the appellant has already had his day in court. Hovey v. Elliott,

supra, is discussed at length both by the majority which distinguishes

it, and in a dissent by Justices Black and Douglas who argue that

Hovey should apply even to an appeal, once the state has undertaken

to provide a system of appeals.

10 Not only will the indigent tenant be unable to file his affidavit of

defense in the dispossessory warrant proceedings, but Georgia eases

consistently deny tenant-plaintiffs injunctive relief against evictions, on

the ground that, even though the tenant may be indigent and unable to

furnish bond, the legal remedy is adequate. Flynn v. Merck, ------ Ga.

------ , 49 S.E.2d 892 (1948); Napier v. Varner, 149 Ga. 586, 101 S.E.2d

29; DeFlorio v. Tarvin, 193 Ga. 760, 20 S.E.2d 29; cf. Worthy v. Tate,

44 Ga. 152.

14

tenant defenses should or should not be heard. Cf. Harper

v. Virginia State Board of Elections, supra.

In Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12, where the Court struck

down as such an invidious discrimination an Illinois ap

pellate procedure requiring indigent criminal defendants

to pay for transcripts of proceedings in order to gain

review of non-constitutional errors, it was said:

Surely no one would contend that either a State or

the Federal Government could constitutionally provide

that defendants unable to pay court costs in advance

should be denied the right to plead not guilty or to

defend themselves in court. Such a law would make

the constitutional promise of a fair trial a worthless

thing. Notice, the right to he heard, and the right to

counsel would under such circumstances be meaning

less promises to the poor.

# # # # #

There is no meaningful distinction between a rule

which would deny the poor the right to defend them

selves in a trial court and one which effectively denies

the poor an adequate appellate review accorded to

all who have money enough to pay the costs in ad

vance. 351 U.S. at 17-18 (emphasis added).

And just as the Court concluded in Griffin that “ [tjhere

can be no equal justice where the kind of trial a man gets

depends on the amount of money he has,” (351 U.S. at 19),

obviously, here, equal justice will be denied if the question

whether a man will get a trial at all is answered by the

amount of money he has.

Indeed, it is difficult to conjecture what might be a valid

reason for closing off the opportunity to defend one’s

rights if the defendant was destitute. Unlike requirements

15

for the payment of fees by plaintiffs11 12 the bond require

ment here, placed upon defendants, does not serve to limit

the filing of frivolous claims.13

Thus, the conclusion is inescapable that just as the Court

held in Griffin that the constitutional prohibitions against

denials of equal protection of the law and due process of

law bar the conditioning of access to the criminal process

on affluence, so they similarly must bar the imposition of

such a condition on an indigent in a civil action before he

may present his defenses to his being divested of valuable

property rights.

11 The giving of a bond by a plaintiff is a frequent limitation on the

right to the use of courts or for extraordinary relief in the federal and

state systems. See 31 U.S.C. § 518 (injunction to stay distress warrant);

29 U.S.C. § 407 (injunction in labor disputes); 28 U.S.C. § 1446 (re

moval of cases); F.R.C.P. 65 (temporary restraining order); Georgia

Code § 39-301 and 302 (forthcoming bonds); Georgia Code 88-702 and

8-801 (claim bond in attachment); Georgia Code § 37-1403 (ne exeat).

However, no similar provisions have been found requiring defendants

to furnish bonds before filing a defense after plaintiffs have selected the

forum.

12 Georgia has an effective device for limiting frivolous defenses. The

defense must be made by affidavit. Title 61, Georgia Code Ann. § 61-303.

Title 26, Ga. Code Ann., §§ 26-4001, 26-4002, would subject the per

juring affiant to criminal penalties. See Sistrunk v. State o f Georgia,

18 Ga. App. 42, 88 S.E. 796 (syllabus: conviction for perjury upon a

false affidavit made in dispossessory proceedings, affirmed).

16

Certiorari Should Be Granted to Decide the Ques

tions Presented Since the Court Below Erred in Its

Determination That Petitioners’ Cases Have Become

Moot.

The court below ruled that since petitioners had been

evicted, “the suits to enjoin their removal from the rented

premises (have) become moot.” (Appendix, p. 6a.) It also

refused to grant petitioners’ prayers for declaratory

judgment adopting language saying “ [wjhere, as here,

the petition shows that the rights of the parties have al

ready accrued and no facts or circumstances are alleged

which show that an adjudication of the plaintiffs’ right is

necessary in order to relieve [them] . . . from the risk of

taking any future undirected action . . . the petition fails

to state a cause of action for declaratory judgment.” (Ap

pendix, p. 6a.)

Whether a case in which a federal constitutional claim

has been asserted has become moot is a federal question

to be decided by this Court in resolving its jurisdiction;

hence, the lower court’s finding of mootness is not binding.

Love v. Griffith, 266 U.S. 32; Liner v. Jafco, 375 U.S. 301,

304, 305, Cf. Ward v. Love County, 253 U.S. 17, 22.

The decision below, if allowed to stand, would conclude

a series of attempts by petitioners to obtain their con

stitutional right to be heard before they are divested of

valuable property rights. In the eviction proceeding they

were met by the challenged bond requirement, which con

stituted an absolute bar. They then filed a petition in equity

to challenge the bond statute. However, after their petition

was denied they were evicted by default because they

could not present their defenses. The Supreme Court

of Georgia held that this action was moot because of that

eviction. In this way the wholly anomalous result was

reached that the state could use an unconstitutional and

17

lienee void proceeding to prevent petitioners from chal

lenging that very proceeding. Thus, if petitioners’ cases

are now moot, it is difficult to imagine how the constitu

tionality of the statute can be ever decided by this Court

or any of the lower Georgia courts.12a Indeed, the statute

would be virtually immune from constitutional challenge.13

Decisions of this Court have made clear that where

acts sought to be enjoined have been performed by coercion

(e.g. by forcible eviction), the case is not moot because

the consequences of the conduct may be set aside by the

subsequent issuance of an injunction. Porter v. Lee, 328

U.S. 246; Texas & N. 0. R. Co. v. Northside Belt R. Co.,

276 U.S. 475, 479.

In Porter v. Lee, the Federal Price Administrator

brought actions in a federal district court under the

Emergency Price Control Act to restrain an eviction

brought by respondent in state court for alleged non-pay

ment of rent. The Administrator’s complaints were dis

missed and pending appeal the tenant vacated his apart

ment. The Circuit Court of Appeals held that the cases

had become moot. This Court reversed the mootness ruling,

reasoning that “ (t)he mere fact that the (tenant) . . . in

order to comply with the writ of possession vacated the

apartment was not enough to end the controversy.” (328

U.S. at 251.) Since the respondent there had completed

the acts sought to be enjoined (the eviction) after having

notice of the injunction suit the Court held that there

was mandatory injunctive power to restore the status

quo, citing, Texas $ N. 0. R. Co., supra.

12a fpjjg summary eviction statute provides that eviction will take place

three days after a dispossessory warrant is obtained unless within that

period the tenant files a counter affidavit and bond pursuant to the

challenged statute. Tit. 61, 5 306, Ga. Code Ann. Sec, R-M 14.

13 The petitioners were also unsuccessful in an attempt to obtain a

federal court injunction against the evictions and the operation o f the

statute. Williams, et al. v. Grimes, C.A. No. 10,025 (Slip Op. 1166, M.D.

Ga.), see fn. 3, supra.

18

Petitioners here brought both state and federal injunc

tive suits to stay their evictions. Certainly, Porter would

bar an assertion that their cases are now moot because

they were unable to stay their evictions, because of Georgia

law, before their cases could reach the appellate court for

decision. Obviously, the Georgia courts have similar powers

to restore petitioners to the status quo.14

In addition to the above, there are other principles by

which this Court may find that there is no mootness bar

to its reaching the important issues presented here. This

Court has frequently decided cases on their merits, even

though the central dispute between parties to the litiga

tion has ended.15 16 Thus, in United States v. Trans-Missouri

14 Although no Georgia cases can be found which specifically grant a

wrongfully evicted tenant the right to be readmitted, petitioners’ prayers

that the dispossessory warrants be vacated, and for such other and fur

ther relief as is just could be read by the Georgia courts as a request

for readmission in the event of eviction. In Lehmann v. West Seventy-

Sixth St. Man. Corp., 67 N.Y.S. 2d 91 (Sup. Ct. N.Y.C. 1946), a New

York Court granted the tenant repossession o f the apartment from which

she had been evicted, saying: "With the setting aside of the warrant of

dispossess, the tenant became entitled to possession o f the premises from

which she had been removed by virtue of the warrant.” (Id. p. 92.) And,

recent New York cases have granted tenants the right to repossession

where the wrongfulness of their evictions arose from non-service of proc

ess. Albany v. White, 46 Misc. 2d 915, 261 Misc. Supp. 2d 361 (1965);

Marluted Realty Corp. v. Decker, 260 N.Y. Supp. 2d 988. Certainly, if

Georgia courts have equitable power to grant a landlord an injunction

against waste by the tenant during his possession, Jones v. Gammon, 123

Ga. 47, 50 S.E. 982, or to prevent a landlord from interfering with the

tenant’s possession during the tenancy, Shoals Power Co. v. Fortson, 138

Ga. 460, 75 S.E. 606, they have power to readmit a tenant to possession

where he proves that the dispossessory warrant was unlawfully executed.

16 The purpose of the litigation is often determinative. See, generally,

Diamond, Federal Jurisdiction To Decide Moot Cases, 94 U. Pa. L. Rev.

125 (1946); Note, Cases Moot On Appeal: A Limit On The Judicial

Power, 103 U. Pa. L. Rev. 772 (1955). Here, the prayer for relief indi

cates a far broader purpose than mere injunction o f the eviction proceed

ings. Among the claims for relief were: (1) that § 61-303 be declared

unconstitutional; (2) that an order be issued to vacate the ex parte order

in the nature of a dispossessory warrant, on the basis o f allegations of

19

Freight Ass’n., 166 TJ.S. 290, 308, and Southern Pacific

Terminal Co. v. Interstate Commerce Commission, 219

U.S. 491, 515, the Court decided appeals on the ground

that the cases were vested with a substantial public in

terest which was not extinguished by disappearance of the

central contest between the parties.

In Trans-Missouri Freight Ass’n., supra, an anti-trust

case, the United States sought both to enjoin an associa

tion of railroads from alleged violations of the Sherman

Act and to dissolve the association. Pending appeal, the

association voluntarily dissolved, but the Court held that

the case had not become moot, stressing the public nature

of the rights being asserted (166 U.S. at 308, 310):

Private parties may settle their controversies at

any time, and rights which a plaintiff may have had

at the time of the commencement of the action may

terminate before judgment is obtained or while the

case is on appeal, and in any such case the court,

being informed of the facts, will proceed no further

in the action. Here, however, there has been no ex

tinguishment of the rights (whatever they are) of the

public, the enforcement of which the government has

endeavored to procure by a judgment of a court under

the provisions of the act of Congress above cited. The

defendants cannot foreclose those rights nor prevent

the assertion thereof by the government as a substan

tial trustee for the public under the act of Congress,

by any such action as has been taken in this case.

fact and exhibits attached to the petition for injunction; (3) that a rule

nisi issue to the Sheriff o f Fulton County restraining him from execut

ing the dispossessory warrant; (4) that petitioner(s) have sueh other

and further relief as is meet and just in the premises (R -W 10, 11, 12;

R-M 11, 12).

20

And, in Southern Pacific Terminal Go., supra, an appeal

by a carrier from an order of the Interstate Commerce

Commission barring the grant of certain privileges to a

shipper, the Court held that there was a continuing public

interest in the legality of certain kinds of I.C.C. orders.

Thus, even though the order expired by its own terms

pending appeal and could not be affected by the Court

judgment, the Court decided the case on the merits:

In the case at bar the order of the Commission may

to some extent (the exact extent it is unnecessary to

define) be the basis of further proceedings. But there

is a broader consideration. The question involved in

the orders of the Interstate Commerce Commission

are usually continuing (as are manifestly those in the

case at bar), and these considerations ought not to

be, as they might be, defeated, by short-terms orders,

capable of repetition, yet evading review, and at one

time the government and at another time the carriers,

have their rights determined by the Commission with

out a chance of redress. (219 U.S. at p. 515.)

In determining the issue of whether an appeal has be

come moot where the central controversy has ended, the

determining factor is whether there is a likelihood of

continuation of the conduct sought to be enjoined. In

Trans-Missouri Freight Ass’n., supra, it appeared that

members of the voluntarily dissolved association of defen

dants would reform another association. And, in Southern

Pacific Terminal Co. the continuing public interest in the

kinds of orders the I.C.C. could lawfully issue was clear.

Similarly, where defendants assert that conduct voluntarily

ceased was not illegal, there is a likelihood that it will be

resumed and this Court has often held such cases are not

moot. Walling v. Helmerich <# Payne, Inc., 323 U.S. 37,

21

42, 43; Goslien Mfg. Co. v. Hubert A. Myers Mfg. Co., 242

U.S. 202, 207, 208.

It is certain that without a determination of the consti

tutionality of § 61-303, the statute will continue to foreclose

untold numbers of indigent tenant-defendants from pre

senting meritorious defenses to summary ejectment claims.

The Marshal of the Civil Court of Fulton County, Georgia

stated (Affidavit, R-W 17; R-M 18) that in Fulton County

alone, in recent months, approximately 1,400 dispossessory

warrants per month were issued, and that defensive plead

ings were filed in less than one per cent (1%) of the cases.

The Attorney General of the State of Georgia argued in

the brief filed below for the State of Georgia, that § 61-303

was a reasonable measure by which Georgia could protect

the property rights of owners of rental property and did

not violate the Fourteenth Amendment.

Because of the seriousness and importance of the ques

tions presented, it is imperative that this Court review

the decision below and resolve these issues.

The Question of the Right of an Indigent Tenant

to Remain in Possession and Defend Against Eviction

Without Posting Substantial Security Required By a

State Statute Is of General Importance.

This case raises an important constitutional issue in the

developing field of the law of poverty—and in a particu

larly crucial area of that field, landlord-tenant law. The

ease of the obtaining of a summary eviction order by the

landlord simply by filing an affidavit, combined with the im

possibility of a poor tenant defending against it because

he cannot post security, permits evictions to occur almost

casually. These evictions may be unwarranted and arbi

trary, and may result only from inability of the tenant

22

to post a security so large in relation to the monthly rent

that it bears no relation to the tenant’s ability to meet his

monthly obligations as they become due.

To a tenant who is poor, eviction raises in the most

extreme form possible the problem of security in housing.

It is important to the development of sound family life

that the family be able to remain in one place for sub

stantial periods of time—to develop stable relationships

with the neighbors, the schools, etc. Family disruption

has long been known to be a crucial agent in maintaining

the cycle of poverty. There is not only a social disruption

cost, but an economic cost in moving which a poor family

has particular difficulty in bearing.16

Within the coniines of one’s income, housing which is

voluntarily chosen by an individual family will probably

be more suitable to its particular needs than housing not

so chosen. No matter how inadequate the housing in which

poor families reside, their chances of finding equal or bet

ter housing upon eviction are rather slim—as the experi

ence with urban renewal programs in city after city has

demonstrated. When a poor person is also a Negro or

other minority group member, as are the petitioners here,

a housing market in which opportunities are already in

adequate because of economic factors becomes much more

severely circumscribed through the operation of prejudice.17

The existence of summary eviction procedures in which

there is a substantial economic obstacle preventing a tenant

16 Alvin L. Schorr, Slums and Social Insecurity (U.S. Government

Printing Office, 1963), pp. 68-73, 86; Carl Sehier, “ Protecting the Inter

ests of the Indigent Tenant: Two Approaches,” 54 California Law Re

view 670 (1966).

17 Schorr, op. cit., pp. 61-68, 81-87, 96-97, 98-120; Millspaugh, “Prob

lems and Opportunities of Relocation,” 26 Law and Contemporary Prob

lems, 6, 20-24 (1961).

23 *

i

from contesting eviction, places an enormous amount of

arbitrary power in the hands of the landlord which he

exercises in collaboration with the State. The existence

of detailed housing codes in many cities demonstrates the

need to prevent non-resident landlords from allowing the

housing in which poor people reside to deteriorate.18 Such

codes may be effective in their intended purpose of secur

ing adequate housing to the poor, only to the extent that

those who are injured by their violation complain to

appropriate authorities about such violations. However,

where a tenant can be easily evicted by a landlord in a

summary proceeding in retaliation for such a complaint,

it is clear that many tenants will be intimidated into suf

fering quietly.19

Several other states have summary eviction statutes

similar to the one in issue which on their face impose a

substantial security requirement for possible damages in

advance on a tenant before permitting him to remain in

possession to defend against eviction. These include:

(1) Arkansas. Arkansas Statutes Annotated (1947), Title

34, §1510; (2) California. California Code of Civil Pro

cedure, § 1166a; (3) Indiana. Burns Indiana Statutes An

notated (1933), §§3-1304 through 3-1306; (4) Mississippi.

Mississippi Code Annotated (1942), Title 7, § 957; (5)

Texas. Texas Rules of Civil Procedure (1955), Rule 740;

(6) Virginia. Virginia Code Annotated (1950), Title 55,

§242; (7) Washington. Revised Code of Washington

18 More than 650 cities have adopted housing codes since 1954. Note,

“ The Enforcement of Municipal Housing Codes,” 78 Harvard Law Re

view 801, 803 (1965); Schorr, op. cit., pp. 87-96.

19 Patricia M. Wald, Law and Poverty: 1965, Report to the National

Conference on Law and Poverty sponsored by the Attorney-General and

the Office of Economic Opportunity of the United States (Washington,

D. C .: 1965), p. 15; Robert S. Schoshinski, “ Remedies of the Indigent

Tenant: Proposal for Change,” 54 Georgetown Law Journal 519, 541

(1966).

24

(1961), § 59.12.100; (8) West Virginia. West Virginia Code

(1961), § 3672.20

The issue of the potential denial of the Constitutionally

required equal protection of the laws to a tenant who is

poor and cannot post substantial security to prevent evic

tion pending adjudication of the merits may therefore be

raised by all of these statutes.

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons, the petition for writ of certiorari

should be granted.

Bespectfully submitted,

J ack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Charles H . J o n e s , J r .

Charles Stephen R alston

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

H oward Moore, J r .

859% Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia 30314

Attorneys for Petitioners

20 It should be noted that while the general procedural laws o f many

states provide that bonds for court costs may be waived in the case of

indigency, as does Georgia (Title 24, §3413), the above cited bond pro

visions are specific requirements o f the landlord-tenant sections of the

respective state statutes apparently intended to secure the landlord’s right

to rent, rather than the payment of court costs to the state. With this

premise, and without considering the possible Constitutional defect of

such a statutory requirement, a State court might conclude that it would

not make sense to waive the tenant’s security requirement on the ground

of the tenant’s indigency—as the Georgia courts have held— even when

there is a general procedural provision waiving bonds for court costs.

APPENDIX

APPENDIX

Order

(March 2, 1966)

F ulton County S uperior Court (G eorgia)

W illie W illiams

vs

J oseph N. Sharper

The petition in the above case having been presented

to the Court for an ex parte interlocutory injunction,

and defendant being present, and objecting to same, and

defendant having made a motion to dismiss the said peti

tion, and after hearing argument thereon:

I t Is Ordered, that the ex parte interlocutory injunction

be denied, and further ordered that the defendant’s motion

to dismiss be sustained, and the petition in the above case

is dismissed.

This 2nd day of March 1966.

/ s / L uther A bruso

Judge, Superior Court, A.J.C.

Minutes 389, P age 273

Filed in office this the

2 day of Mar., 1966

W. M. Callaway

Deputy Clerk

2a

Order

(March. 2, 1966)

F ulton County Superior Court (Georgia)

Sam Martin

vs

J oseph N. Shaffer

The petition in the above case having been presented

to the Court for an ex parte interlocutory injunction,

and defendant being present, and objecting to same, and

defendant having made a motion to dismiss the said peti

tion, and after hearing argument thereon:

I t I s Ordered, that the ex parte interlocutory injunction

be denied, and further ordered that the defendant’s motion

to dismiss be sustained, and the petition in the above case

is dismissed.

This 2nd day of March 1966.

/s/ L uther A bruso

Judge, Superior Court, A.J.C.

M inutes 389, P age 273

Filed in office this the

2 day of Mar., 1966

R uby H. W ard

Deputy Clerk

(Decided: June 23, 1966)

S upreme Court op Georgia

23559. W illiams v. Shafper

23560. Martin v. Shaffer

Quillian, Justice. Willie Williams and Sam Martin in

stituted separate actions against their landlord Joseph N.

Shaffer. These cases are in all material aspects alike. In

each case, brought through the same counsel, the injunction

is sought to prevent the plaintiff’s eviction in a dispos-

sessory warrant proceeding on the sole grounds that “an

notated Code section 61-303” is unconstitutional in that it

requires the tenant in such an action to file a bond, as a

condition to entering a counter affidavit. The trial judge

upon oral motion struck the petition in each case.

The constitutional attack on the statute is couched in

the following language: “petitioner avers that he has no

plain and adequate remedy at law, by reason of the facial

unconstitutionality of Title 61, Georgia Code Annotated,

Section 303. Said statute violates the due process and

equal protection of law clauses of the Fourteenth Amend

ment, United States Constitution, and Article I, para

graphs 3 and 25, Constitution of the State of Georgia of

1945, in that, said statute invidiously bars petitioner from

obtaining judicial review in the courts of the State of

Georgia of any defenses which he may have to said eviction

solely because of his poverty and denies the petitioner

equal access to the courts of the State of Georgia. Said

statute reads as follows: ‘61-303. . . . The tenant may

arrest the proceedings and prevent the removal of himself

and his goods from the land by declaring on oath that his

lease or term of rent has not expired, and that he is not

Opinion

4a

holding possession of the premises over and beyond his

term, or that the rent claimed is not due, or that he does

not hold the premises, either by lease, or rent, or at will,

or by sufferance, or otherwise, from the person who made

the affidavit on which the warrant issued, or from anyone

under whom he claims the premises, or from anyone claim

ing the premises under him: Provided, such tenant shall

at the same time tender a bond with good security, payable

to the landlord, for the payment of such sum, with costs,

as may be recovered against him on the trial of the

case. . . As applied said statute bars petitioner from

directly challenging the dispossessory proceedings in the

courts of the State of Georgia solely because of his poverty

and thereby denied petitioner due process and equal pro

tection of the law in violation of the Fourteenth Amend

ment, United States Constitution and of Article II, para

graphs 3 and 25, Constitution of the State of Georgia of

1945.” The appeals in each case are identical and each

reads that the plaintiff “appeals to the Supreme Court of

Georgia from the final order and judgment denying plain

tiff’s prayers for injunctive relief and dismissing his peti

tion on oral motion of the defendant. . . .”

The same enumeration of error and statements are con

tained in each appellant’s brief, which read: “1. Whether

Title 61, Georgia Code Annotated, Section 303, requiring

the posting of a bond as a condition precedent to making

a defense by a tenant in dispossessory proceedings, con

stitutes a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment, Consti

tution of the United States, and of Article I, paragraphs 3

and 25, Constitution of the State of Georgia of 1945, where

the tenant is impoverished and unable to provide such

bond. . . . [Grounds 2 and 3 need not be set out here.]

Appellant abandons enumeration of error 2 (a), (b) and

Opinion

5a

3 and does not insist on them on appeal. Appellant relies

entirely upon Ms challenge to the constitutionality of Sec

tion 303 as the grounds for reversal.” It is frankly stated

in each brief: “The court below, on March 2, 1966, dis

missed the petition and denied all relief, without allowing

Sheriff Grimes to be named as a party-defendant. Appel

lant then, on March 2, 1965, filed a notice of appeal. The

court below refused to stay the dispossessory proceedings

and on March 5, 1966, the Sheriff of Fulton County evicted

appellant from the premises.”

In an effort to set forth a right to a declaratory judg

ment each petition alleges: “there is an actual controversy

existing between him and the defendant as to petitioner’s

right to resist said dispossessory proceedings without post

ing bond and to proceed on a pauper’s affidavit.” There

is no allegation of facts or circumstances which show that

an adjudication of the plaintiff’s rights is necessary in

order to relieve the plaintiff from the risk of taking any

future undirected action incident to his rights. Incidental

to the prayer for injunction is the following prayer: “ that

the petitioner have a declaratory judgment declaring, ad

judging and decreeing Title 61, Georgia Code Annotated,

Section 303, unconstitutional, null and void, upon its face

and as applied, under the due process and equal protection

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, United States Con

stitution, and Article II, paragraphs 3 and 25, Constitu

tion of the State of Georgia of 1945.” Held:

The Appellate Practice Act of 1965, embodied in Code

Ann. §6-701 (Ga. L. 1965, pp. 18, 20), brings forward the

provision contained in previous Codes: “Nothing in this

paragraph shall require the appellate court to pass upon

questions which are rendered moot.” This court held in

Glower v. Langley, 153 Ga. 154 (------ S E ------ ) : “Excep

tion is taken to the refusal of an injunction to restrain

Opinion

6a

the execution of a dispossessory warrant. The brief of

counsel for the plaintiff recites that ‘since the filing of the

bill of exceptions in this case, about ten days ago, plaintiff

was dispossessed by the marshall of the municipal court;

she is no longer in possession of the premises involved in

this action; and therefore the questions involved are moot.’

The bill of exceptions is therefore dismissed.” As held in

Griffin v. Grantham, 220 Ga. 474 (----- SE2d------- ) : “ since

all that was sought to be enjoined has been done, the case

has become moot and the writ of error must be dismissed.”

Similar pronouncements are found in Pickett v. Georgia,

Fla. &c. R. Co., 214 Ga. 263 (— SE 2d------ ) ; Lorenz v.

HeKalb County, 215 Ga. 731 (------ SE2d ------) ; Espey v.

Village of North Atlanta, 218 Ga. 429 (------ SE2d ------•);

Woods v. State of Ga., 219 Ga. 503 (------ SE2d ------ ) ;

Trainer v. City of Covington, 220 Ga. 228 (-—— SE2d------ ).

The appellants having been evicted in the present cases,

the suits to enjoin their removal from the rented premises

become moot.

“ ‘The object of the declaratory judgment is to permit

determination of a controversy before obligations are

repudiated or rights are violated.’ Rowan v. Herring,

214 Ga. 370, 374 (105 SE2d 29). . . . Where, as here, the

petition shows that the rights of the parties have already

accrued and no facts or circumstances are alleged which

show that an adjudication of the plaintiff’s rights is neces

sary in order to relieve the plaintiffs from the risk of

taking any future undirected action incident to their rights,

which action without direction would jeopardize their

interests, the petition fails to state a cause of action for

declaratory judgment.” So the suits as related to declara

tory judgment not only become moot, but under the quoted

pronouncement set forth no cause for that relief.

Appeal dismissed. All the Justices concur.

Opinion

Judgment

(Decided: June 23, 1966)

S upreme Court of Georgia

The Honorable Supreme Court met pursuant to adjourn

ment. The following judgment was rendered:

W illie W illiams v. J oseph S haffer et al.

This case came before this court upon an appeal from

the Superior Court of Fulton County; and, after argument

had, it is considered and adjudged that the appeal be dis

missed. All the Justices concur.

Judgment

(Decided: June 23, 1966)

Supreme Court of Georgia

The Honorable Supreme Court met pursuant to adjourn

ment. The following judgment was rendered:

Sam Martin v. J oseph Shaffer et al.

This case came before this court upon an appeal from

the Superior Court of Fulton County; and, after argument

had, it is considered and adjudged that the appeal be dis

missed. All the Justices concur.

8a

Denial o f Rehearing

(Decided: July 7, 1966)

Supreme Court op Georgia

The Honorable Supreme Court met pursuant to adjourn

ment. The following order was passed:

W illie W illiams v. J oseph S haffer et al.

Upon consideration of the motion for a rehearing filed

in this case, it is ordered that it be hereby denied.

Denial of Rehearing

(Decided: July 7, 1966)

Supreme Court of Georgia

The Honorable Supreme Court met pursuant to adjourn

ment. The following order was passed:

Sam Martin v. J oseph Shaffer et al.

Upon consideration of the motion for a rehearing filed

in this case, it is ordered that it be hereby denied.

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C .< 4 §^ > 219