Hurd v. Hodge Court Opinion

Public Court Documents

May 3, 1948

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Hurd v. Hodge Court Opinion, 1948. a6d22088-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/55a07dd7-6b33-4b2c-9e51-c7b93ca84423/hurd-v-hodge-court-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

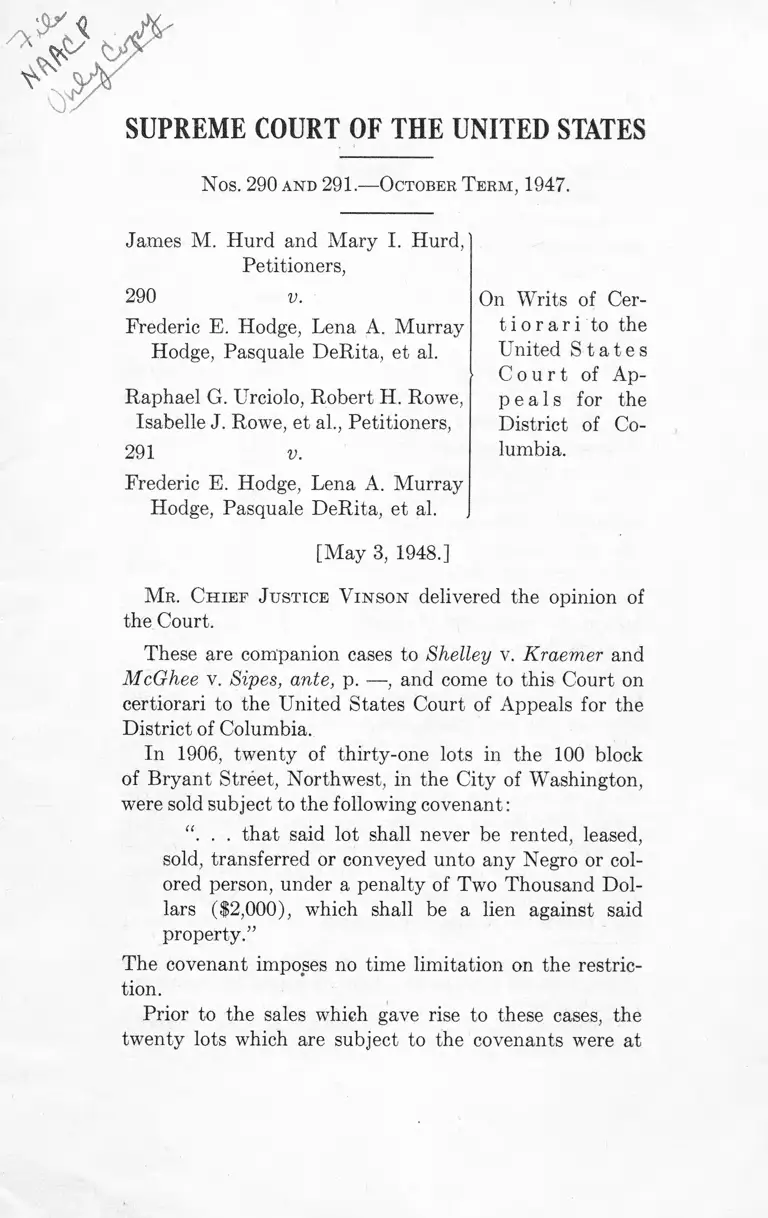

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Nos. 290 and 291.— October Term, 1947.

James M. Hurd and Mary I. Hurd,

Petitioners,

290 v.

Frederic E. Hodge, Lena A. Murray

Hodge, Pasquale DeRita, et al.

Raphael G. Urciolo, Robert H. Rowe,

Isabelle J. Rowe, et al., Petitioners,

291 v.

Frederic E. Hodge, Lena A. Murray

Hodge, Pasquale DeRita, et al.

[M ay 3, 1948.]

M r. Chief Justice V inson delivered the opinion of

the Court.

These are companion cases to Shelley v. Kraemer and

McGhee v. Sipes, ante, p. — , and come to this Court on

certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the

District of Columbia.

In 1906, twenty of thirty-one lots in the 100 block

of Bryant Street, Northwest, in the City of Washington,

-were sold subject to the following covenant:

“ . . . that said lot shall never be rented, leased,

sold, transferred or conveyed unto any Negro or col

ored person, under a penalty of Two Thousand Dol

lars ($2,000), which shall be a lien against said

property.”

The covenant imposes no time limitation on the restric

tion.

Prior to the sales which gave rise to these cases, the

twenty lots which are subject to the covenants were at

On Writs of Cer-

t i o r a r i to the

United S t a t e s

C o u r t of Ap

p e a l s for the

District of Co

lumbia.

2 HURD v. HODGE.

all times owned and occupied by white persons, except

for a brief period when three of the houses were occupied

by Negroes who were eventually induced to move without

legal action. The remaining eleven lots in the same

block,1 however, are not subject to a restrictive agreement

and, as found by the District Court, were occupied by

Negroes for the twenty years prior to the institution of

this litigation.

These cases involve seven of the twenty lots which

are subject to the terms of the restrictive covenants. In

No. 290, petitioners Hurd, found by the trial court to

be Negroes,2 purchased one of the restricted properties

from the white owners. In No. 291, petitioner Urciolo,

a white real estate dealer, sold and conveyed three of the

restricted properties to the Negro petitioners Rowe, Sav

age, and Stewart. Petitioner Urciolo also owns three

other lots in the block subject to the covenants. In both

cases, the Negro petitioners are presently occupying as

homes the respective properties which have been con

veyed to them.

Suits were instituted in the District Court by respond

ents, who own other property in the block subject to the

terms of the covenants, praying for injunctive relief to

enforce the terms of the restrictive agreement. The

cases were consolidated for trial, and after a hearing,

the court entered a judgment declaring null and void the

deeds of the Negro petitioners; enjoining petitioner Urci

olo and one Ryan, the white property owners who had

sold the houses to the Negro petitioners, from leasing,

selling or conveying the properties to any Negro or col

ored person; enjoining the Negro petitioners from leasing

1 All of the residential property in the block is on the south side

of the street, the northern side of the street providing a boundary

for a public park.

2 Petitioner James M. Hurd maintained that he is not a Negro but

a Mohawk Indian.

HURD v. HODGE. 3

or conveying the properties and directing those petition

ers “ to remove themselves and all of their personal

belongings” from the premises within sixty days.

The United States Court of Appeals for the District

of Columbia, with one justice dissenting, affirmed the

judgment of the District Court.3 The majority of the

court was of the opinion that the action of the District

Court was consistent with earlier decisions of the Court

of Appeals and that those decisions should be held deter

minative in these cases.

Petitioners have attacked the judicial enforcement of

the restrictive covenants in these cases on a wide variety

of grounds. Primary reliance, however, is placed on the

contention that such governmental action on the part

of the courts of the District of Columbia is forbidden by

the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment of the

Federal Constitution.4

Whether judicial enforcement of racial restrictive agree

ments by the federal courts of the District of Columbia

violates the Fifth Amendment has never been adjudicated

by this Court. In Corrigan v. Buckley, 271 U. S. 323

(1926), an appeal was taken to this Court from a judg

ment of the United States Court of Appeals for the

District of Columbia which had affirmed an order of

the lower court granting enforcement to a restrictive

covenant. But as was pointed out in our opinion in

Shelley v. Kraemer, supra, the only constitutional issue

which had been raised in the lower courts in the Corrigan

case, and, consequently, the only constitutional question

3 — U. S. App. D. C. — , 162 F. 2d 233 (1947).

4 Other contentions made by petitioners include the following:

judicial enforcement of the covenants is contrary to § 1978 of the

Revised Statutes derived from the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and to

treaty obligations of the United States contained in the United Na

tions’ charter; enforcement of the covenants is contrary to the public

policy; enforcement of the covenants is inequitable.

4 HURD v. HODGE.

before this Court on appeal, related to the validity of

the private agreements as such. Nothing in the opinion

of this Court in that case, therefore, may properly be

regarded as an adjudication of the issue presented by

petitioners in this case which concerns, not the validity

of the restrictive agreements standing alone, but the

validity of court enforcement of the restrictive covenants

under the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment.5

See Shelley v. Kraemer, supra at — .

This Court has declared invalid municipal ordinances

restricting occupancy in designated areas to persons of

specified race and color as denying rights of white sellers

and Negro purchasers of property, guaranteed by the

due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Bu

chanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 (1917); Harmon v.

Tyler, 273 U. S. 668 (1927); Richmond v. Deans, 281

U. S. 704 (1930). Petitioners urge that judicial enforce

ment of the restrictive covenants by courts of the District

5 Prior to the present litigation, the United States Court of Appeals

for the District of Columbia has considered cases involving enforce

ment of racial restrictive agreements on at least eight occasions.

Corrigan v. Buckley, 55 App. D. C. 30, 299 F. 899 (1924); Torrey v.

Woljes, 56 App. D. C. 4, 6 F. 2d 702 (1925); Russell v. Wallace, 58

App. D. C. 357, 30 F. 2d 981 (1929); Cornish v. O’Donoghue, 58 App.

D. C. 359, 30 F. 2d 983 (1929); Grady v. Garland, 67 App. D. C. 73,

89 F. 2d 817 (1937); Hundley v. Gorewitz, 77 U. S. App. D. C. 48,

132 F. 2d 23 (1942); Mays v. Burgess, 79 U. S. App. D. C. 343, 147

F. 2d 869 (1945); Mays v. Burgess, 80 U. S. App. D. C. 236, 152 F.

2d 123 (1945).

In Corrigan v. Buckley, supra, the first of the cases decided by the

United States Court of Appeals and relied on in most of the subse

quent decisions, the opinion of the court contains no consideration of

the specific issues presented to this Court in these cases. An appeal

from the decision in Corrigan v. Buckley, was dismissed by this Court.

271 U. S. 323 (1926). See discussion supra. In Hundley v. Gorewitz,

supra, the United States Court of Appeals refused enforcement of a

restrictive agreement where changes in the character of the neighbor

hood would have rendered enforcement inequitable.

HURD v. HODGE. 5

of Columbia should likewise be held to deny rights of

white sellers and Negro purchasers of property, guaran

teed by the due process clause of the Fifth Amendment.

Petitioners point out that this Court in Hirabayashi v.

United States, 320 U. S. 81, 100 (1943), reached its deci

sion in a case in which issues under the Fifth Amendment

were presented, on the assumption that “ racial discrimi

nations are in most circumstances irrelevant and therefore

prohibited. . . And see Korematsu v. United States,

323 U. S. 214, 216 (1944).

Upon full consideration, however, we have found it

unnecessary to resolve the constitutional issue which peti

tioners advance; for we have concluded that judicial

enforcement of restrictive covenants by the courts of the

District of Columbia is improper for other reasons herein

after stated.6 7

Section 1978 of the Revised Statutes, derived from § 1

of the Civil Rights Act of 1866/ provides:

“ All citizens of the United States shall have the

same right, in every State and Territory, as is en

6 It is a well-established principle that this Court will not decide

constitutional questions where other grounds are available and dis

positive of the issues of the case. Recent expressions of that policy

are to be found in Alma Motor Co. v. Timken-Detroit Axle Co., 329

U. S. 129 (1946); Rescue Army v. Municipal Court, 331 U. S. 549

(1947).

7 14 Stat. 27. Section 1 of the Act provided: “ . . . That all per

sons born in the United States and not subject to any foreign power,

excluding Indians not taxed, are hereby declared to be citizens of

the United States; and such citizens, of every race and color, without

regard to any previous condition of slavery or involuntary servitude,

except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been

duly convicted, shall have the same right, in every State and Terri

tory in the United States, to make and enforce contracts, to sue, be

parties, and give evidence, to inherit, purchase, lease, sell, hold, and

convey real and personal property, and to full and equal benefit of all

laws and proceedings for the security of person and property, as is

enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be subject to like punishment,

6 HURD v. HODGE.

joyed by white citizens thereof to inherit, purchase,

lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal prop

erty.” 8

All the petitioners in these cases, as found by the Dis

trict Court, are citizens of the United States. We have

no doubt that, for the purposes of this section, the District

of Columbia is included within the phrase “ every State

and Territory.” 9 Nor can there be doubt of the con

stitutional power of Congress to enact such legislation

with reference to the District of Columbia.10

We may start with the proposition that the statute

does not invalidate private restrictive agreements so long

as the purposes of those agreements are achieved by the

parties through voluntary adherence to the terms. The

action toward which the provisions of the statute under

consideration is directed is governmental action. Such

was the holding of Corrigan v. Buckley, supra.

In considering whether judicial enforcement of restric

tive covenants is the kind of governmental action which

the first section of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 was in

tended to prohibit, reference must be made to the scope

pains, and penalties, and to none other, any law, statute, ordinance,

regulation, or custom, to the contrary notwithstanding.”

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 was reenacted in § 18 of the Act

of May 31, 1870, 16 Stat. 144, passed subsequent to the adoption

of the Fourteenth Amendment. Section 1977 of the Revised Statutes

(8 U. S. C. § 41), derived from § 16 of the Act of 1870, which in turn

was patterned after § 1 of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, provides:

“ All persons within the jurisdiction of the United States shall have

the same right in every State and Territory to make and enforce

contracts, to sue, be parties, give evidence, and to the full and equal

benefit of all laws and proceedings for the security of persons and

property as is enjoyed by white citizens, and shall be subject to like

punishment, pains, penalties, taxes, licenses, and exactions of every

kind, and to no other.”

88 U .S .C . §42.

9 Cf. Talbott v. Silver Bow County, 139 U. S. 438, 444 (1891).

10 See Keller v. Potomac Electric Power Co., 261 U. S. 428, 442-443

(1923).

HURD v. HODGE. 7

and purposes of the Fourteenth Amendment; for that

statute and the Amendment were closely related both

in inception and in the objectives which Congress sought

to achieve.

Both the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the joint resolu

tion which was later adopted as the Fourteenth Amend

ment were passed in the first session of the Thirty-Ninth

Congress.11 Frequent references to the Civil Rights Act

are to be found in the record of the legislative debates on

the adoption of the Amendment.12 It is clear that in

many significant respects the statute and the Amendment

were expressions of the same general congressional policy.

Indeed, as the legislative debates reveal, one of the pri

mary purposes of many members of Congress in sup

porting the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment was

to incorporate the guaranties of the Civil Rights Act of

1866 in the organic law of the land.13 Others supported

11 The Civil Rights Act of 1866 became law on April 9, 1866. The

Joint Resolution submitting the Fourteenth Amendment to the States

passed the House of Representatives on June 13, 1866, having previ

ously passed the Senate on June 8. Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st

Sess. 3148-3149, 3042.

12 See, e. g., Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 2459, 2461, 2462,

2465, 2467, 2498, 2506,2511,2538,2896,2961,3035.

13 Thus, Mr. Thayer of Pennsylvania, speaking in the House of Rep

resentatives, stated: “ As I understand it, it is but incorporating in

the Constitution of the United States the principle of the civil rights

bill which has lately become a law, . . . in order . . . that that

provision so necessary for the equal administration of the law, so

just in its operation, so necessary for the protection of the funda

mental rights of citizenship, shall be forever incorporated in the

Constitution of the United States.” Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st

Sess. 2465. And note the remarks of Mr. Stevens of Pennsylvania

in reporting to the House the joint resolution which was subsequently

adopted as the Fourteenth Amendment. Id. at 2459. See also id.

at 2462, 2896, 2961. That such was understood to be a primary

purpose of the Amendment is made clear not only from statements

of the proponents of the Amendment but of its opponents. Id. at

2467, 2538. See Flack, The Adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment

94-96.

8 HURD v. HODGE.

the adoption of the Amendment in order to eliminate

doubt as to the constitutional validity of the Civil Rights

Act as applied to the States.14

The close relationship between § 1 of the Civil Rights

Act and the Fourteenth Amendment was given specific

recognition by this Court in Buchanan v. Warley, supra

at 79. There, the Court observed that, not only through

the operation of the Fourteenth Amendment, but also by

virtue of the “ statutes enacted in furtherance of its pur

pose,” including the provisions here considered, a colored

man is granted the right to acquire property free from

interference by discriminatory state legislation. In Shel

ley v. Kraemer, supra, we have held that the Fourteenth

Amendment also forbids such discrimination where im

posed by state courts in the enforcement of restrictive

covenants. That holding is clearly indicative of the con

struction to be given to the relevant provisions of the

Civil Rights Act in their application to the Courts of the

District of Columbia.

Moreover, the explicit language employed by Congress

to effectuate its purposes, leaves no doubt that judicial

enforcement of the restrictive covenants by the courts

of the District of Columbia is prohibited by the Civil

Rights Act. That statute, by its terms, requires that all

citizens of the United States shall have the same right

“ as is enjoyed by white citizens . . . to inherit, purchase,

lease, sell, hold, and convey real and personal property.”

14 No doubts were expressed as to the constitutionality of the Civil

Rights Act in its application to the District of Columbia. Senator

Poland of Vermont stated: “ It certainly seems desirable that no doubt

should be left existing as to the power of Congress to enforce prin

ciples lying at the very foundation of all republican government if

they be denied or violated by the States, and I cannot doubt but

that every Senator will rejoice in aiding to remove, all doubt upon this

power of Congress.” Cong. Globe, 39th Cong., 1st Sess. 2961. See

also id. at 2461,2498,2506, 2511,2896, 3035.

HURD v. HODGE. 9

That the Negro petitioners have been denied that right

by virtue of the action of the federal courts of the Dis

trict is clear. The Negro petitioners entered into con

tracts of sale with willing sellers for the purchase of

properties upon which they desired to establish homes.

Solely because of their race and color they are confronted

with orders of court divesting their titles in the properties

and ordering that the premises be vacated. White sellers,

one of whom is a petitioner here, have been enjoined

from selling the properties to any Negro or colored person.

Under such circumstances, to suggest that the Negro

petitioners have been accorded the same rights as white

citizens to purchase, hold, and convey real property is

to reject the plain meaning of language. We hold that

the action of the District Court directed against the Negro

purchasers and the white sellers denies rights intended

by Congress to be protected by the Civil Rights Act

and that, consequently, the action cannot stand.

But even in the absence of the statute, there are other

considerations which would indicate that enforcement of

restrictive covenants in these cases is judicial action con

trary to the public policy of the United States,15 and

as such should be corrected by this Court in the exercise

of its supervisory powers over the courts of the District

of Columbia.16 The power of the federal courts to enforce

15See United States v. Hutcheson, 312 U. S. 219, 235 (1941);

Johnson v. United States, 163 F. 30, 32 (1908).

16 Section 240 (a) of the Judicial Code, 43 Stat. 938, 28 U. S. C.

§347 (a), provides: “ In any case, civil or criminal, in a circuit court

of appeals, or in the Court of Appeals of the District of Columbia,

it shall be competent for the Supreme Court of the United States,

upon the petition of any party thereto, whether Government or other

litigant, to require by certiorari, either before or after a judgment

or decree by such lower court, that the cause be certified to the

Supreme Court for determination by it with the same power and

authority, and with like effect, as if the cause had been brought

there by unrestricted writ of error or appeal.”

10 HURD v. HODGE.

the terms of private agreements is at all times exercised

subject to the restrictions and limitations of the public

policy of the United States as manifested in the Consti

tution, treaties, federal statutes, and applicable legal prece

dents.17 Where the enforcement of private agreements

would be violative of that policy, it is the obligation of

courts to refrain from such exertions of judicial power.18

We are here concerned with action of federal courts

of such a nature that if taken by the courts of a State

would violate the prohibitory provisions of the Four

teenth Amendment. Shelley v. Kraemer, supra. It is

not consistent with the public policy of the United States

to permit federal courts in the Nation’s capital to exercise

general equitable powers to compel action denied the

state courts where such state action has been held to be

violative of the guaranty of the equal protection of the

laws.19 We cannot presume that the public policy of the

United States manifests a lesser concern for the protection

of such basic rights against discriminatory action of fed

eral courts than against such action taken by the courts

of the States.

Reversed.

Mr. Justice R eed, Mr. Justice Jackson, and Mr.

Justice R utledge took no part in the consideration or

decision of these cases.

17 Muschany v. United States, 324 U. S. 49, 66 (1945). And see

License Tax Cases, 5 Wall. 462, 469 (1867).

18 Cf. Kennett v. Chambers, 14 How. 38 (1852); Tool Co. v. Norris,

2 Wall. 45 (1865); Sprott v. United States, 20 Wall. 459 (1874);

Trist v. Child, 21 Wall. 441 (1875); Oscanyan v. Arms Co., 103 U. S.

261 (1881); Burt v. Union Central Life Insurance Co., 187 U. S.

362 (1902); Sage v. Hampe, 235 U. S. 99 (1914). And see Beasley

v. Texas & Pacific R. Co., 191 U. S. 492 (1903).

18 Cf. Gandoljo v. Hartman, 49 F. 181, 183 (1892).

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Nos. 290 and 291.— October T erm, 1947.

James M. Hurd and Mary I. Hurd,

Petitioners,

290 v.

Frederic E. Hodge, Lena A. Murray

Hodge, Pasquale DeRita, et al.

Raphael G. Urciolo, Robert H. Rowe,

Isabelle J. Rowe, et al., Petitioners,

291 v.

Frederic E. Hodge, Lena A. Murray

Hodge, Pasquale DeRita, et al.

[M ay 3, 1948.]

M r. Justice Frankfurter, concurring.

In these cases, the plaintiffs ask equity to enjoin white

property owners who are desirous of selling their houses

to Negro buyers simply because the houses were subject

to an original agreement not to have them pass into

Negro ownership. Equity is rooted in conscience. An

injunction is, as it always has been, “ an extraordinary

remedial process which is granted, not as a matter of

right but in the exercise of a sound judicial discretion.”

Morrison v. Work, 266 U. S. 481, 490. In good con

science, it cannot be “ the exercise of a sound judicial

discretion” by a federal court to grant the relief here

asked for when the authorization of such an injunction

by the States of the Union violates the Constitution—

and violates it, not for any narrow technical reason, but

for considerations that touch rights so basic to our society

that, after the Civil War, their protection against invasion

by the States was safeguarded by the Constitution. This

is to me a sufficient and conclusive ground for reaching

the Court’s result.

On Writs of Cer

t i o r a r i to the

United S t a t e s

C o u r t of Ap-

p e a l s for the

District of Co

lumbia.