Correspondence between Clerks Re: Hunt v. Cromartie Syllabus and Court Opinion

Public Court Documents

April 18, 2001

42 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Cromartie Hardbacks. Correspondence between Clerks Re: Hunt v. Cromartie Syllabus and Court Opinion, 2001. fe9ef341-e60e-f011-9989-002248226c06. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/55b1f625-4b92-4de7-89c0-f755711ef19a/correspondence-between-clerks-re-hunt-v-cromartie-syllabus-and-court-opinion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

@ »

®ffice of the Clerk

Supreme Qonrt of the United States

Washington, B. ¢. 205%3-0001

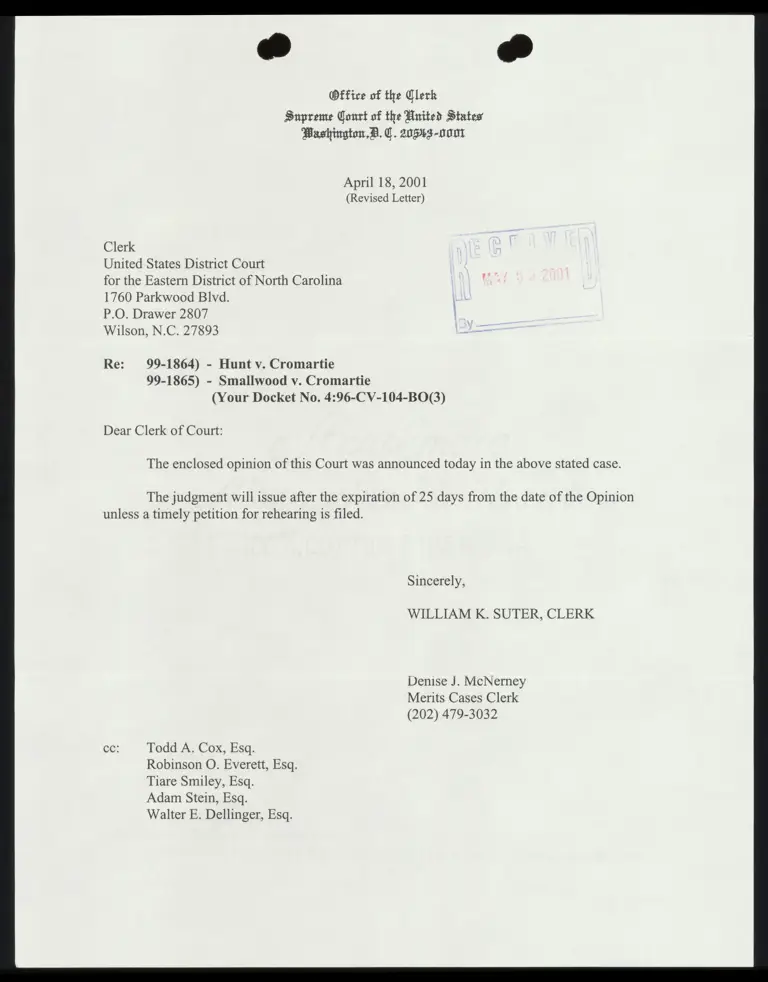

April 18, 2001

(Revised Letter)

Clerk

United States District Court

for the Eastern District of North Carolina

1760 Parkwood Blvd.

P.O. Drawer 2807

Wilson, N.C. 27893

Re: 99-1864) - Hunt v. Cromartie

99-1865) - Smallwood v. Cromartie

(Your Docket No. 4:96-CV-104-BO(3)

Dear Clerk of Court:

The enclosed opinion of this Court was announced today in the above stated case.

The judgment will issue after the expiration of 25 days from the date of the Opinion

unless a timely petition for rehearing is filed.

Sincerely,

WILLIAM K. SUTER, CLERK

Denise J. McNerney

Merits Cases Clerk

(202) 479-3032

Todd A. Cox, Esq.

Robinson O. Everett, Esq.

Tiare Smiley, Esq.

Adam Stein, Esq.

Walter E. Dellinger, Esq.

®ffice of the (lerk

Supreme Qonrt of the Vnited States

Washington, B. ¢. 20543-0001

April 18, 2001

Clerk

United States District Court

for the Eastern District of North Carolina

1760 Parkwood Blvd.

P.O. Drawer 2807

Wilson, N.C. 27893

Re: 99-1864) - Hunt v. Cromartie

99-1865) - Smallwood v. Cromartie

(Your Docket No. 4:96-CV-104-BO(3) )

Dear Clerk of Court:

The enclosed opinion of this Court was announced today in the above stated case.

The mandate issued today pursuant to Court order.

Sincerely,

WILLIAM K. SUTER, CLERK

Denise J. McNerney

Merits Cases Clerk

(202) 479-3032

Todd A. Cox, Esq.

Robinson O. Everett, Esq.

Tiare Smiley, Esq.

Adam Stein, Esq.

Walter E. Dellinger, III, Esq.

# #

(Bench Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2000 1

Syllabus

NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is

being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued.

The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been

prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader.

See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Syllabus

HUNT, GOVERNOR OF NORTH CAROLINA, ET AL. v.

CROMARTIE ET AL.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

No. 99-1864. Argued November 27, 2000—Decided April 18, 2001*

After this Court found that North Carolina’s legislature violated the

Constitution by using race as the predominant factor in drawing its

Twelfth Congressional District's 1992 boundaries, Shaw v. Hunt, 517

U.S. 899, the State redrew those boundaries. A three-judge District

Court subsequently granted appellees summary judgment, finding

that the new 1997 boundaries had also been created with racial con-

siderations dominating all others. This Court reversed, finding that

there was a genuine issue of material fact as to whether the evidence

was consistent with a race-based objective or the constitutional po-

litical objective of creating a safe Democratic seat. Hunt v. Cromartie,

526 U.S. 541. Among other things, this Court relied on evidence pro-

posed to be submitted by appellants to conclude that, because the

State’s African-American voters overwhelmingly voted Democratic,

one could not easily distinguish a legislative effort to create a major-

ity-minority district from a legislative effort to create a safely Demo-

cratic one; that data showing voter registration did not indicate how

voters would actually vote; and that data about actual behavior could

affect the litigation’s outcome. Id., at 547-551. On remand, the Dis-

trict Court again held, after a 3-day trial, that the legislature had used

race driven criteria in drawing the 1997 boundaries. It based that con-

clusion on three findings—the district’s shape, its splitting of towns

and counties, and its heavily African-American voting population—

that this Court had considered when it found summary judgment inap-

*Together with No. 99-1865, Smallwood et al. v. Cromartie et al.,

also on appeal from the same court.

HUNT v. CROMARTIE

Syllabus

propriate, and on the new finding that the legislature had drawn the

boundaries to collect precincts with a high racial, rather than political,

identification.

Held: The District Court’s conclusion that the State violated the Equal

Protection Clause in drawing the 1997 boundaries is based on clearly

erroneous findings. Pp. 5-23.

(a) The issue here is evidentiary: whether there is adequate sup-

port for the District Court’s finding that race, rather than politics,

drove the legislature’s districting decision. Those attacking the dis-

trict have the demanding burden of proof to show that a facially neu-

tral law is unexplainable on grounds other than race. Cromartie, su-

pra, at 546. Because the underlying districting decision falls within a

legislature’s sphere of competence, Miller v. Johnson, 515 U. S. 900,

915, courts must exercise extraordinary caution in adjudicating claims

such as this one, id., at 916, especially where, as here, the State has ar-

ticulated a legitimate political explanation for its districting decision

and the voting population is one in which race and political affiliation

are highly coordinated, see Cromartie, supra, at 551-552. This Court

will review the District Court's findings only for “clear error,” asking

whether “on the entire evidence” the Court is “left with the definite and

firm conviction that a mistake has been committed.” United States v.

United States Gypsum Co., 333 U. S. 364, 395. An extensive review of

the District Court's findings is warranted here because there was no in-

termediate court review, the trial was not lengthy, the key evidence

consisted primarily of documents and expert testimony, and credibility

evaluations played a minor role. Pp. 5-7.

(b) The critical District Court determination that “race, not politics,”

predominantly explains the 1997 boundaries rests upon the three find-

ings that this Court found insufficient to support summary judgment,

and which cannot in and of themselves, as a matter of law, support the

District Court’s judgment here. See Bush v. Vera, 517 U. S. 952, 968.

Its determination also rests upon five new subsidiary findings, which

this Court also cannot accept as adequate. First, the District Court

primarily relied on evidence of voting registration, not voting behav-

ior, which is precisely the kind of evidence that this Court found in-

adequate the last time the case was here. White registered Demo-

crats “cross-over” to vote Republican more often than do African-

Americans, who register and vote Democratic between 95% and 97%

of the time. Thus, a legislature trying to secure a safe Democratic

seat by placing reliable Democratic precincts within a district may

end up with a district containing more heavily African-American pre-

cincts for political, not racial, reasons. Second, the evidence to which

appellees’ expert, Dr. Weber, pointed—that a reliably Democratic

voting population of 60% is necessary to create a safe Democratic

Cite as: 532 U.S. (2001) 3

Syllabus

seat, but this district was 63% reliable; that certain white-Democratic

precincts were excluded while African-American-Democratic pre-

cincts were included; that one precinct was split between Districts 9

and 12; and that other plans would have created a safely Democratic

district with fewer African-American precincts—simply does not pro-

vide significant additional support for the District Court’s conclusion.

Also, portions of Dr. Weber's testimony not cited by the District Court

undercut his conclusions. Third, the District Court, while not ac-

cepting the contrary conclusion of appellants’ expert, Dr. Peterson,

did not (and as far as the record reveals, could not) reject much of the

significant supporting factual information he provided, which showed

that African-American Democratic voters were more reliably Demo-

cratic and that District 12’s boundaries were drawn to include reli-

able Democrats. Fourth, a statement about racial balance made by

Senator Cooper, the legislative redistricting leader, shows that the

legislature considered race along with other partisan and geographic

considerations, but says little about whether race played a predomi-

nant role. And an e-mail sent by Gerry Cohen, a legislative staff

member responsible for drafting districting plans, offers some sup-

port for the District Court’s conclusion, but is less persuasive than

the kinds of direct evidence that this Court has found significant in

other redistricting cases. Fifth, appellees’ maps summarizing voting

behavior evidence tend to refute the District Court’s “race, not poli-

tics,” conclusion. Pp. 7-22.

(c) The modicum of evidence supporting the District Court’s conclu-

sion—the Cohen e-mail, Senator Cooper's statement, and some aspects

of Dr. Weber's testimony—taken together, does not show that racial

considerations predominated in the boundaries’ drawing, because race

in this case correlates closely with political behavior. Where majority-

minority districts are at issue and racial identification correlates highly

with political affiliation, the party attacking the boundaries must show

at the least that the legislature could have achieved its legitimate politi-

cal objectives in alternative ways that are comparably consistent with

traditional districting principles and that those alternatives would have

brought about significantly greater racial balance. Because appellees

failed to make any such showing here, the District Court's contrary

findings are clearly erroneous. Pp. 22-23.

Reversed.

BREYER, J., delivered the opinion of the Court, in which STEVENS,

O’CONNOR, SOUTER, and GINSBURG, JdJ., joined. THOMAS, J., filed a dis-

senting opinion, in which REHNQUIST, C. J., and SCALIA and KENNEDY,

JdJ., joined.

Cite as: 532 U. S. (2001)

Opinion of the Court

NOTICE: This opinion is subject to formal revision before publication in the

preliminary print of the United States Reports. Readers are requested to

notify the Reporter of Decisions, Supreme Court of the United States, Wash-

ington, D. C. 20543, of any typographical or other formal errors, in order

that corrections may be made before the preliminary print goes to press.

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Nos. 99-1864 and 99-1865

JAMES B. HUNT, Jr., GOVERNOR OF NORTH

CAROLINA, ET AL., APPELLANTS

99-1864 v.

MARTIN CROMARTIE ET AL.

ALFRED SMALLWOOD, ET AL., APPELLANTS

99-1865 .

MARTIN CROMARTIE ET AL.

ON APPEALS FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR

THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

[April 18, 2001]

JUSTICE BREYER delivered the opinion of the Court.

In this appeal, we review a three-judge District Court’s

determination that North Carolina’s legislature used race

as the “predominant factor” in drawing its 12th Congres-

sional District's 1997 boundaries. The court’s findings, in

our view, are clearly erroneous. We therefore reverse its

conclusion that the State violated the Equal Protection

Clause. U. S. Const., Amdt. 14, §1.

I

This “racial districting” litigation is before us for the

fourth time. Our first two holdings addressed North

Carolina’s former Congressional District 12, one of two

North Carolina congressional districts drawn in 1992 that

contained a majority of African-American voters. See

HUNT v. CROMARTIE

Opinion of the Court

Shaw v. Reno, 509 U.S. 630 (1993) (Shaw I); Shaw v.

Hunt, 517 U. S. 899 (1996) (Shaw II).

A

In Shaw I, the Court considered whether plaintiffs’

factual allegation—that the legislature had drawn the

former district's boundaries for race-based reasons—if

true, could underlie a legal holding that the legislature

had violated the Equal Protection Clause. The Court held

that it could. It wrote that a violation may exist where the

legislature’s boundary drawing, though “race neutral on

its face,” nonetheless can be understood only as an effort

to “separate voters into different districts on the basis of

race,” and where the “separation lacks sufficient justifica-

tion.” 509 U. S., at 649.

In Shaw II, the Court reversed a subsequent three-judge

District Court’s holding that the boundary-drawing law in

question did not violate the Constitution. This Court

found that the district's “unconventional,” snakelike

shape, the way in which its boundaries split towns and

counties, its predominately African-American racial make-

up, and its history, together demonstrated a deliberate

effort to create a “majority-black” district in which race

“could not be compromised,” not simply a district designed

to “protec[t] Democratic incumbents.” 517 U. S., at 902—

903, 905-907. And the Court concluded that the legisla-

ture’s use of racial criteria was not justified. Id., at 909-

918.

B

Our third holding focused on a new District 12, the

boundaries of which the legislature had redrawn in 1997.

Hunt v. Cromartie, 526 U.S. 541 (1999). A three-judge

District Court, with one judge dissenting, had granted

summary judgment in favor of those challenging the dis-

# *

Cite as: 532 U.S. (2001) 3

Opinion of the Court

trict’s boundaries. The court found that the legislature

again had “used criteria . . . that are facially race driven,”

in violation of the Equal Protection Clause. App. to Juris.

Statement 262a. It based this conclusion upon “uncontro-

verted material facts” showing that the boundaries created

an unusually shaped district, split counties and cities,

and in particular placed almost all heavily Democratic-

registered, predominantly African-American voting pre-

cincts, inside the district while locating some heavily

Democratic-registered, predominantly white precincts,

outside the district. This latter circumstance, said the

court, showed that the legislature was trying to maximize

new District 12's African-American voting strength, not

the district's Democratic voting strength. Ibid.

This Court reversed. We agreed with the District Court

that the new district's shape, the way in which it split

towns and counties, and its heavily African-American

voting population all helped the plaintiffs’ case. 526 U. S.,

at 547-549. But neither that evidence by itself, nor when

coupled with the evidence of Democratic registration, was

sufficient to show, on summary judgment, the unconstitu-

tional race-based objective that plaintiffs claimed. That is

because there was a genuine issue of material fact as to

whether the evidence also was consistent with a constitu-

tional political objective, namely, the creation of a safe

Democratic seat. Id., at 549-551.

We pointed to the affidavit of an expert witness for

defendants, Dr. David W. Peterson. Dr. Peterson offered

to show that, because North Carolina’s African-American

voters are overwhelmingly Democratic voters, one cannot

easily distinguish a legislative effort to create a majority-

African-American district from a legislative effort to create

a safely Democratic district. Id., at 550. And he also

provided data showing that registration did not indicate

how voters would actually vote. Id., at 550-551. We

agreed that data showing how voters actually behave, not

4 HUNT v. CROMARTIE

Opinion of the Court

data showing only how those voters are registered, could

affect the outcome of this litigation. Ibid. We concluded

that the case was “not suited for summary disposition”

and we reversed the District Court. Id., at 554.

C

On remand, the parties undertook additional discovery.

The three-judge District Court held a 3-day trial. And the

court again held (over a dissent) that the legislature had

unconstitutionally drawn District 12's new 1997 bounda-

ries. It found that the legislature had tried “(1) [to] cur[e]

the [previous district’s] constitutional defects” while also

“(2) drawing the plan to maintain the existing partisan

balance in the State’s congressional delegation.” App. to

Juris. Statement 11a. It added that to “achieve the second

goal,” the legislature “drew the new plan (1) to avoid

placing two incumbents in the same district and (2) to

preserve the partisan core of the existing districts.” Ibid.

The court concluded that the “plan as enacted largely

reflects these directives.” Ibid. But the court also found

“as a matter of fact that the General Assembly . . . used

criteria . . . that are facially race driven” without any

compelling justification for doing so. Id., at 28a.

The court based its latter, constitutionally critical,

conclusion in part upon the district’s snakelike shape, the

way in which it split cities and towns, and its heavily

African-American (47%) voting population, id., at 1la—

17a—all matters that this Court had considered when

it found summary judgment inappropriate, Cromartie,

supra, at 544. The court also based this conclusion upon a

specific finding—absent when we previously considered

this litigation—that the legislature had drawn the

boundaries in order “to collect precincts with high racial

identification rather than political identification.” App. to

Juris. Statement 28a—29a (emphasis added).

This last-mentioned finding rested in turn upon five

# »

Cite as: 532 U.S. (2001) 5

Opinion of the Court

subsidiary determinations:

(1) that “the legislators excluded many heavily-

Democratic precincts from District 12, even when those

precincts immediately border the Twelfth and would

have established a far more compact district,” id., at

25a; see also id., at 29a (“more heavily Democratic pre-

cincts . . . were bypassed . . . in favor of precincts with

a higher African-American population”);

(2) that “[a]dditionally, Plaintiffs’ expert, Dr. Weber,

showed time and again how race trumped party affilia-

tion in the construction of the 12th District and how

political explanations utterly failed to explain the com-

position of the district,” id., at 26a;

(3) that Dr. Peterson’s testimony was “‘unreliable’ and not

relevant,” id., at 27a (citing testimony of Dr. Weber);

(4) that a legislative redistricting leader, Senator Roy

Cooper, had alluded at the time of redistricting “to a

need for ‘racial and partisan’ balance,” ibid.; and

(5) that the Senate’s redistricting coordinator, Gerry

Cohen, had sent Senator Cooper an e-mail reporting

that Cooper had “moved Greensboro Black community

into the 12th, and now need[ed] to take [about] 60,000

out of the 12th,” App. 369; App. to Juris. Statement

27a—28a.

The State and intervenors filed a notice of appeal. 28

U.S. C. §1253. We noted probable jurisdiction. 530 U. S.

1260 (2000). And we now reverse.

II

The issue in this case is evidentiary. We must deter-

mine whether there is adequate support for the District

Court's key findings, particularly the ultimate finding that

the legislature’s motive was predominantly racial, not

political. In making this determination, we are aware

that, under Shaw I and later cases, the burden of proof on

the plaintiffs (who attack the district) is a “demanding

6 HUNT v. CROMARTIE

Opinion of the Court

one.” Miller v. Johnson, 515 U.S. 900, 928 (1995)

(O'CONNOR, d., concurring). The Court has specified that

those who claim that a legislature has improperly used

race as a criterion, in order, for example, to create a ma-

jority-minority district, must show at a minimum that the

“legislature subordinated traditional race-neutral dis-

tricting principles . . . to racial considerations.” Id., at 916

(majority opinion). Race must not simply have been “a

motivation for the drawing of a majority minority district,”

Bush v. Vera, 517 U.S. 952, 959 (1996) (O'CONNOR, d.,

principal opinion) (emphasis in original), but “the ‘predomi-

nant factor’ motivating the legislature’s districting deci-

sion,” Cromartie, 526 U. S., at 547 (quoting Miller, supra,

at 916) (emphasis added). Plaintiffs must show that a

facially neutral law “‘is “unexplainable on grounds other

than race.””” Cromartie, supra, at 546 (quoting Shaw I,

509 U. S., at 644, in turn quoting Arlington Heights v.

Metropolitan Housing Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252,

266 (1977)).

The Court also has made clear that the underlying

districting decision is one that ordinarily falls within a

legislature’s sphere of competence. Miller, 515 U. S., at

915. Hence, the legislature “must have discretion to exer-

cise the political judgment necessary to balance competing

interests,” itbid., and courts must “exercise extraordinary

caution in adjudicating claims that a State has drawn

district lines on the basis of race,” id., at 916 (emphasis

added). Caution is especially appropriate in this case,

where the State has articulated a legitimate political expla-

nation for its districting decision, and the voting population

is one in which race and political affiliation are highly

correlated. See Cromartie, supra, at 551-552 (noting that

“[e]lvidence that blacks constitute even a supermajority in

one congressional district while amounting to less than a

plurality in a neighboring district will not, by itself, suffice

to prove that a jurisdiction was motivated by race in draw-

»

Citeas: 5321.85. (2001 7

Opinion of the Court

ing its district lines when the evidence also shows a high

correlation between race and party preference”).

We also are aware that we review the District Court's

findings only for “clear error.” In applying this standard,

we, like any reviewing court, will not reverse a lower

court’s finding of fact simply because we “would have

decided the case differently.” Anderson v. Bessemer City,

470 U. S. 564, 573 (1985). Rather, a reviewing court must

ask whether “on the entire evidence,” it is “left with the

definite and firm conviction that a mistake has been com-

mitted.” United States v. United States Gypsum Co., 333

U. S. 364, 395 (1948).

Where an intermediate court reviews, and affirms, a

trial court’s factual findings, this Court will not “lightly

overturn” the concurrent findings of the two lower courts.

E.g., Neil v. Biggers, 409 U. S. 188, 193, n. 3 (1972). But in

this instance there is no intermediate court, and we are

the only court of review. Moreover, the trial here at issue

was not lengthy and the key evidence consisted primarily

of documents and expert testimony. Credibility evalua-

tions played a minor role. Accordingly, we find that an

extensive review of the District Court’s findings, for clear

error, is warranted. See Bose Corp. v. Consumers Union of

United States, Inc., 466 U. S. 485, 500-501 (1984). That

review leaves us “with the definite and firm conviction,”

United States Gypsum Co., supra, at 395, that the District

Court’s key findings are mistaken.

ITI

The critical District Court determination—the matter

for which we remanded this litigation—consists of the

finding that race rather than politics predominantly ex-

plains District 12’s 1997 boundaries. That determination

rests upon three findings (the district’s shape, its splitting

of towns and counties, and its high African-American

voting population) that we previously found insufficient to

8 HUNT v. CROMARTIE

Opinion of the Court

support summary judgment. Cromartie, supra, at 547—

549. Given the undisputed evidence that racial identifica-

tion is highly correlated with political affiliation in North

Carolina, these facts in and of themselves cannot, as a

matter of law, support the District Court’s judgment. See

Vera, 517 U. S., at 968 (O'CONNOR, J., principal opinion)

(“If district lines merely correlate with race because they

are drawn on the basis of political affiliation, which cor-

relates with race, there is no racial classification to jus-

tify”). The District Court rested, however, upon five new

subsidiary findings to conclude that District 12's lines are

the product of no “mer[e] correlat[ion],” ibid., but are

instead a result of the predominance of race in the legisla-

ture’s line-drawing process. See supra, at 5.

In considering each subsidiary finding, we have given

weight to the fact that the District Court was familiar

with this litigation, heard the testimony of each witness,

and considered all the evidence with care. Nonetheless,

we cannot accept the District Court’s findings as adequate

for reasons which we shall spell out in detail and which we

can summarize as follows:

First, the primary evidence upon which the District

Court relied for its “race, not politics,” conclusion is evi-

dence of voting registration, not voting behavior; and that

is precisely the kind of evidence that we said was inade-

quate the last time this case was before us. See infra, at

9-10. Second, the additional evidence to which appellees’

expert, Dr. Weber, pointed, and the statements made by

Senator Cooper and Gerry Cohen, simply do not provide

significant additional support for the District Court's

conclusion. See infra, at 10-15, 17-19. Third, the District

Court, while not accepting the contrary conclusion of

appellants’ expert, Dr. Peterson, did not (and as far as the

record reveals, could not) reject much of the significant

supporting factual information he provided. See infra, at

15-17. Fourth, in any event, appellees themselves have

>»

Cite as: 532 U.S. (2001) 9

Opinion of the Court

provided us with charts summarizing evidence of voting

behavior and those charts tend to refute the court’s “race

not politics” conclusion. See infra, at 19-21; Appendixes,

infra.

A

The District Court primarily based its “race, not poli-

tics,” conclusion upon its finding that “the legislators

excluded many heavily-Democratic precincts from District

12, even when those precincts immediately border the

Twelfth and would have established a far more compact

district.” App. to Juris. Statement 25a; see also id., at 29a

(“M]ore heavily Democratic precincts . .. were bypassed

. in favor of precincts with a higher African-American

population”). This finding, however—insofar as it differs

from the remaining four—rests solely upon evidence that

the legislature excluded heavily white precincts with high

Democratic Party registration, while including heavily

African-American precincts with equivalent, or lower,

Democratic Party registration. See id., at 13a—14a, 17a.

Indeed, the District Court cites at length figures showing

that the legislature included “several precincts with racial

compositions of 40 to 100 percent African-American,”

while excluding certain adjacent precincts “with less than

35 percent African-American population” but which con-

tain between 54% and 76% registered Democrats. Id., at

13a—14a.

As we said before, the problem with this evidence is that

it focuses upon party registration, not upon voting behav-

ior. And we previously found the same evidence, compare

ibid. (District Court’s opinion after trial) with id., at 249a—

250a (District Court’s summary judgment opinion), inade-

quate because registration figures do not accurately pre-

dict preference at the polls. See id., at 174a; see also

Cromartie, 526 U. S., at 550-551 (describing Dr. Peter-

son’s analysis as “more thorough” because in North Caro-

10 HUNT v. CROMARTIE

Opinion of the Court

lina, “party registration and party preference do not al-

ways correspond”). In part this is because white voters

registered as Democrats “cross-over” to vote for a Republi-

can candidate more often than do African-Americans, who

register and vote Democratic between 95% and 97% of the

time. See Record, Deposition of Gerry Cohen 37-42 (dis-

cussing data); App. 304 (stating that white voters cast

about 60% to 70% of their votes for Republican candi-

dates); id., at 139 (Dr. Weber's testimony that 95% to 97%

of African-Americans register and vote as Democrats); see

also id., at 118 (testimony by Dr. Weber that registration

data were the least reliable information upon which to

predict voter behavior). A legislature trying to secure a

safe Democratic seat is interested in Democratic voting

behavior. Hence, a legislature may, by placing reliable

Democratic precincts within a district without regard to

race, end up with a district containing more heavily Afri-

can-American precincts, but the reasons would be political

rather than racial.

Insofar as the District Court relied upon voting registra-

tion data, particularly data that were previously before us,

it tells us nothing new; and the data do not help answer

the question posed when we previously remanded this

litigation. Cromartie, supra, at 551.

B

The District Court wrote that “[a]dditionally, [p]laintiffs’

expert, Dr. Weber, showed time and again how race

trumped party affiliation in the construction of the 12th

District and how political explanations utterly failed to

explain the composition of the district.” App. to Juris.

Statement 26a. In support of this conclusion, the court

relied upon six different citations to Dr. Weber's trial

testimony. We have examined each reference.

is

Cite as: 532 U.S. (2001)

Opinion of the Court

1

At the first cited pages of the trial transcript, Dr. Weber

says that a reliably Democratic voting population of 60% is

sufficient to create a safe Democratic seat. App. 91. Yet,

he adds, the legislature created a more-than-60% reliable

Democratic voting population in District 12. Hence (we

read Dr. Weber to infer), the legislature likely was driven

by race, not politics. Tr. 163; App. 314-315.

The record indicates, however, that, although Dr. Weber

is right that District 12 is more than 60% reliably Demo-

cratic, it exceeds that figure by very little. Nor did Dr.

Weber ask whether other districts, unchallenged by ap-

pellees, were significantly less “safe” than was District 12.

Id., at 148. In fact the figures the legislature used showed

that District 12 would be 63% reliably Democratic. App. to

Juris. Statement 80a (Democratic vote over three represen-

tative elections averaged 63%). By the same measures, at

least two Republican districts (Districts 6 and 10) are 61%

reliably Republican. Ibid. And, as Dr. Weber conceded,

incumbents might have urged legislators (trying to main-

tain a six/six Democrat/Republican delegation split) to

make their seats, not 60% safe, but as safe as possible.

App. 149. In a field such as voting behavior, where figures

are inherently uncertain, Dr. Weber's tiny calculated

percentage differences are simply too small to carry sig-

nificant evidentiary weight.

2

The District Court cited two parts of the transcript

where Dr. Weber testified about a table he had prepared

listing all precincts in the six counties, portions of which

make up District 12. Tr. 204-205, 262. Dr. Weber said

that District 12 contains between 39% and 56% of the

precincts (depending on the county) that are more-than-

40% reliably Democratic, but it contains almost every

precinct with more-than-40% African-American voters.

HUNT v. CROMARTIE

Opinion of the Court

Id., at 204-205. Why, he essentially asks, if the legisla-

ture had had politics primarily in mind, would its effort to

place reliably Democratic precincts within District 12 not

have produced a greater racial mixture?

Dr. Weber's own testimony provides an answer to this

question. As Dr. Weber agreed, the precincts listed in the

table were at least 40% reliably Democratic, but virtually

all the African-American precincts included in District 12

were more than 40% reliably Democratic. Moreover, none

of the excluded white precincts were as reliably Democratic

as the African-American precincts that were included in the

district. App. 140. Yet the legislature sought precincts that

were reliably Democratic, not precincts that were 40%-

reliably Democratic, for obvious political reasons.

Neither does the table specify whether the excluded

white-reliably-Democratic precincts were located near

enough to District 12’s boundaries or each other for the

legislature as a practical matter to have drawn District

12’s boundaries to have included them, without sacrificing

other important political goals. The contrary is suggested

by the fact that Dr. Weber's own proposed alternative

plan, see i1d., at 106-107, would have pitted two incum-

bents against each other (Sue Myrick, a Republican from

former District 9 and Mel Watt, a Democrat from former

District 12). Dr. Weber testified that such a result—*a

very competitive race with one of them losing their seat’ —

was desirable. Id., at 153. But the legislature, for politi-

cal, not racial, reasons, believed the opposite. And it drew

its plan to protect incumbents—a legitimate political goal

recognized by the District Court. App. to Juris. Statement

11a.

For these reasons, Dr. Weber's table offers little insight

into the legislature’s true motive.

3

The next part of the transcript the District Court cited

@

Cite as: 532 U.S. (2001) 13

Opinion of the Court

contains Dr. Weber's testimony about a Mecklenburg

County precinct (precinct 77) which the legislature split

between Districts 9 and 12. Tr. 221. Dr. Weber appar-

ently thought that the legislature did not have to split this

precinct, placing the more heavily African-American seg-

ment within District 12—unless, of course, its motive was

racial rather than political. But Dr. Weber simultane-

ously conceded that he had not considered whether Dis-

trict 9s incumbent Republican would have wanted the

whole of precinct 77 left in her own district where it would

have burdened her with a significant additional number of

reliably Democratic voters. App. 156-157. Nor had Dr.

Weber “test[ed]” his conclusion that this split helped to

show a racial (rather than political) motive, say, by ad-

justing other boundary lines and determining the political,

or other nonracial, consequences of such adjustments. Id.,

at 132.

The maps in evidence indicate that to have placed all of

precinct 77 within District 12 would have created a Dis-

trict 12 peninsula that invaded District 9, neatly dividing

that latter district in two, see id., at 496—a conclusive

nonracial reason for the legislature’s decision not to do so.

4

The District Court cited Dr. Weber's conclusion that

“race is the predominant factor.” Tr. 251. But this state-

ment of the conclusion is no stronger than the evidence

that underlies it.

5

The District Court's final citation is to Dr. Weber's

assertion that there are other ways in which the legisla-

ture could have created a safely Democratic district with-

out placing so many primarily African-American districts

within District 12. Id., at 288. And we recognize that

some such other ways may exist. But, unless the evidence

14 HUNT v. CROMARTIE

Opinion of the Court

also shows that these hypothetical alternative districts

would have better satisfied the legislature’s other nonra-

cial political goals as well as traditional nonracial dis-

tricting principles, this fact alone cannot show an im-

proper legislative motive. After all, the Constitution does

not place an affirmative obligation upon the legislature to

avoid creating districts that turn out to be heavily, even

majority, minority. It simply imposes an obligation not to

create such districts for predominantly racial, as opposed

to political or traditional, districting motivations. And Dr.

Weber's testimony does not, at the pages cited, provide

evidence of a politically practical alternative plan that

the legislature failed to adopt predominantly for racial

reasons.

6

In addition, we have read the whole of Dr. Weber's

testimony, including portions not cited by the District

Court. Some of those portions further undercut Dr.

Weber's conclusions. Dr. Weber said, for example, that he

had developed those conclusions while under the errone-

ous impression that the legislature’s computer-based

districting program provided information about racial, but

not political, balance. App. 137-138; see also id., at 302

(reflecting Dr. Weber's erroneous impression in the declara-

tion he submitted to the District Court). He also said he

was not aware of “anything about political dynamics going

on in the [l]egislature involving” District 12, id., at 135,

sometimes expressing disdain for a process that we have

cautioned courts to respect, id., at 150-151; Miller, 515

U. S., at 915-916.

Other portions support Dr. Weber's conclusions. Dr.

Weber testified, for example, about a different alternative

plan that, in his view, would have provided both greater

racial balance and political security, namely, a plan that

the legislature did enact in 1998, and which has been in

*

Cite as: 532 U. S. (2001) 15

Opinion of the Court

effect during the time the courts have been reviewing the

constitutionality of the 1997 plan. App. 156-157. The

existence of this alternative plan, however, cannot help

appellees significantly. Although it created a somewhat

more compact district, it still divides many communities

along racial lines, while providing fewer reliably Demo-

cratic District 12 voters and transferring a group of highly

Democratic precincts into two safely Republican districts,

namely, the 5th and 6th Districts, which political result

the 1997 plan sought to avoid. See Tr. 352, 355. Fur-

thermore, the 1997 plan before this Court, unlike the 1998

plan, joined three major cities in a manner legislators

regarded as reflecting “a real commonality of urban inter-

ests, with inner city schools, urban health care ... prob-

lems, public housing problems.” App. 430 (statement of

Sen. Winner); see also id., at 421 (statement of Sen. Mar-

tin). Consequently, we cannot tell whether the existence

of the 1998 plan shows that the 1997 plan was drawn with

racial considerations predominant. And, in any event, the

District Court did not rely upon the existence of the 1998

plan to support its ultimate conclusion. See Kelley v.

Everglades Drainage Dist, 319 U. S. 415, 420-422 (1943)

(per curiam).

We do not see how Dr. Weber's testimony, taken as a

whole, could have provided more than minimal support for

the District Court's conclusion that race predominantly

underlay the legislature’s districting decision.

C

The District Court found that the testimony of the

State’s primary expert, Dr. Peterson, was “ ‘unreliable’ and

not relevant.” App. to Juris. Statement 27a (quoting Dr.

Weber and citing Tr. 222-224, 232). Dr. Peterson’s testi-

mony was designed to show that African-American Demo-

cratic voters were more reliably Democratic and that

District 12's boundaries were drawn to include reliable

16 HUNT v. CROMARTIE

Opinion of the Court

Democrats. Specifically, Dr. Peterson compared precincts

immediately within District 12 and those immediately

without to determine whether the boundaries of the dis-

trict corresponded better with race than with politics. The

principle underlying Dr. Peterson’s analysis is that if the

district were drawn with race predominantly in mind, one

would expect the boundaries of the district to correlate

with race more than with politics.

The pages cited in support of the District Court's rejec-

tion of Dr. Peterson’s conclusions contain testimony by Dr.

Weber, who says that Dr. Peterson’s analysis is unreliable

because (1) it “ignor[es] the core” of the district, id., at 223,

and (2) it fails to take account of the fact that different

precincts have different populations, id., at 223-224. The

first matter—ignoring the “core”—apparently reflects Dr.

Weber's view that in context the fact that District 12's

heart or “core” is heavily African-American by itself shows

that the legislature's motive was predominantly racial, not

political. The District Court did not argue that the racial

makeup of a district’s “core” is critical. Nor do we see why

“core” makeup alone could help the court discern the

relevant legislative motive. Nothing here suggests that

only “core” makeup could answer the “political/racial”

question that this Court previously found critical. Cro-

martie, 526 U. S., at 551-552.

The second matter—that Dr. Peterson’s boundary seg-

ment analysis did not account for differences in population

between precincts—relates to one aspect of Dr. Peterson’s

testimony. Appellants presented Dr. Peterson’s testimony

and data in support of four propositions: first, that regis-

tration figures do not accurately reflect actual voting

behavior, see App. to Juris. Statement 173a—174a; second,

that African-Americans are more reliable Democrats than

whites, see id., at 159a—160a; third, that political affilia-

tion explains splitting cities and counties as well as does

race, see id., at 189a, 191a-192a, 182a-185a; and fourth,

@

Cite as: 532 U.S. (2001) 17

Opinion of the Court

that differences in the racial and political makeup of the

precincts just inside and outside the boundaries of District

12 show that politics is as good an explanation as is race

for the district's boundaries, see id., at 161a—167a; 181la—

182a. The District Court's criticism of Dr. Peterson’s testi-

mony at most affects the reliability of the fourth element

of Dr. Peterson’s testimony, his special boundary segment

analysis. The District Court's criticism of Dr. Peterson’s

boundary segment analysis does not undermine the data

related to the split communities. The criticism does not

undercut Dr. Peterson’s presentation of statistical evi-

dence showing that registration was a poor indicator of

party preference and that African-Americans are much

more reliably Democratic voters, nor have we found in the

record any significant evidence refuting that data.

At the same time, appellees themselves have used the

information available in the record to create maps com-

paring the district’s boundaries with Democrat/Republican

voting behavior. See Appendixes A, B, and C, infra.

Because no one challenges the accuracy of these maps, we

assume that they are reliable; and we can assume that Dr.

Peterson’s testimony is reliable insofar as it confirms what

the maps themselves contain and appellees themselves

concede. Those maps, with certain exceptions discussed

below, see infra, at 19-21, further indicate that the legis-

lature drew boundaries that, in general, placed more-

reliably Democratic voters inside the district, while plac-

ing less-reliably Democratic voters outside the district.

And that fact, in turn, supports the State’s answers to the

questions we previously found critical.

D

The District Court also relied on two pieces of “direct”

evidence of discriminatory intent.

18 HUNT v. CROMARTIE

Opinion of the Court

1

The court found that a legislative redistricting leader,

Senator Roy Cooper, when testifying before a legislative

committee in 1997, had said that the 1997 plan satisfies a

“need for ‘racial and partisan’ balance.” App. to Juris.

Statement 27a. The court concluded that the words “racial

balance” referred to a 10-to-2 Caucasian/African-American

balance in the State’s 12-member congressional delega-

tion. Ibid. Hence, Senator Cooper had admitted that the

legislature had drawn the plan with race in mind.

Senator Cooper’s full statement reads as follows:

“Those of you who dealt with Redistricting before re-

alize that you cannot solve each problem that you en-

counter and everyone can find a problem with this

Plan. However, I think that overall it provides for a

fair, geographic, racial and partisan balance through-

out the State of North Carolina. I think in order to

come to an agreement all sides had to give a little bit,

but I think we've reached an agreement that we can

live with.” App. 460.

We agree that one can read the statement about “racial

. .. balance” as the District Court read it—to refer to the

current congressional delegation’s racial balance. But

even as so read, the phrase shows that the legislature

considered race, along with other partisan and geographic

considerations; and as so read it says little or nothing

about whether race played a predominant role compara-

tively speaking. See Vera, 517 U. S., at 958 (O'CONNOR, dJ.,

principal opinion) (“Strict scrutiny does not apply merely

because redistricting is performed with consciousness of

race”); see also Miller, 515 U. S., at 916 (legislatures “will

... almost always be aware of racial demographics”); Shaw

I, 509 U. S., at 646 (same).

Rl

Cite as: 532 U.S. (2001) 19

Opinion of the Court

9

ded

The second piece of “direct” evidence relied upon by the

District Court is a February 10, 1997, e-mail sent from

Gerry Cohen, a legislative staff member responsible for

drafting districting plans, to Senator Cooper and Senator

Leslie Winner. Cohen wrote: “I have moved Greensboro

Black community into the 12th, and now need to take

[about] 60,000 out of the 12th. I await your direction on

this.” App. 369.

The reference to race—i.e., “Black community’—is obvi-

ous. But the e-mail does not discuss the point of the refer-

ence. It does not discuss why Greensboro’s African-

American voters were placed in the 12th District; it does

not discuss the political consequences of failing to do so; it

is addressed only to two members of the legislature; and it

suggests that the legislature paid less attention to race in

respect to the 12th District than in respect to the 1st

District, where the e-mail provides a far more extensive,

detailed discussion of racial percentages. It is less persua-

sive than the kinds of direct evidence we have found signifi-

cant in other redistricting cases. See Vera, supra, at 959

(O'CONNOR, J., principal opinion) (State conceded that one

of its goals was to create a majority-minority district);

Miller, supra, at 907 (State set out to create majority-

minority district); Shaw II, 517 U. S., at 906 (recounting

testimony by Cohen that creating a majority-minority dis-

trict was the “principal reason” for the 1992 version of Dis-

trict 12). Nonetheless, the e-mail offers some support for

the District Court’s conclusion.

E

As we have said, we assume that the maps appended to

appellees’ brief reflect the record insofar as that record

describes the relation between District 12's boundaries

and reliably Democratic voting behavior. Consequently

we shall consider appellees’ related claims, made on ap-

20 HUNT v. CROMARTIE

Opinion of the Court

peal, that the maps provide significant support for the

District Court, in that they show how the legislature

might have “swapped” several more heavily African-

American District 12 precincts for other less heavily

African-American adjacent precincts—without harming its

basic “safely Democratic” political objective. Cf. supra, at

10-11.

First, appellees suggest, without identifying any specific

swap, that the legislature could have brought within

District 12 several reliably Democratic, primarily white,

precincts in Forsyth County. See Brief for Appellees 30.

None of these precincts, however, is more reliably Demo-

cratic than the precincts immediately adjacent and within

District 12. See Appendix A, infra (showing Demo-

cratic strength reflected by Republican victories in each

precinct); App. 484 (showing Democratic strength re-

flected by Democratic registration). One of them, the

Brown/Douglas Recreation Precinct, is heavily African-

American. See ibid. And the remainder form a buffer

between the home precinct of Fifth District Representative

Richard Burr and the District 12 border, such that their

removal from District 5 would deprive Representative

Burr of a large portion of his own hometown, making him

more vulnerable to a challenge from elsewhere within his

district. App. to Juris. Statement 209a; App. 623. Conse-

quently the Forsyth County precincts do not significantly

help appellees’ “race not politics” thesis.

Second, appellees say that the legislature might have

swapped two District 12 Davidson County precincts

(Thomasville 1 and Lexington 3) for a District 6 Guilford

County precinct (Greensboro 17). See Brief for Appellees

30, n. 25. Whatever the virtues of such a swap, however,

it would have diminished the size of District 12, geo-

graphically producing an unusually narrow isthmus link-

ing District 12’s north with its south and demographically

producing the State’s smallest district, deviating by about

# *

Cite as: 5321.8. (2001) 21

Opinion of the Court

1,300 below the legislatively endorsed ideal mean of

552,386 population. Traditional districting considerations

consequently militated against any such swap. See Rec-

ord, Deposition of Linwood Lee Jones 122 (stating that

legislature’s goal was to keep deviations from ideal popu-

lation to less than 1,000); App. 199 (testimony of Sen.

Cooper to same effect).

Third, appellees suggest that, in Mecklenburg County,

two District 12 precincts (Charlotte 81 and LCI-South) be

swapped with two District 9 precincts (Charlotte 10 and

21). See Brief for Appellees 30, n. 25. This suggestion is

difficult to evaluate, as the parties provide no map that

specifically identifies each precinct in Mecklenburg

County by name. Nonetheless, from what we can tell,

such a swap would make the district marginally more

white (decreasing the African-American population by

about 300 persons) while making the shape more ques-

tionable, leaving the precinct immediately to the south of

Charlotte 81 jutting out into District 9. We are not con-

vinced that this proposal materially advances appellees’

claim.

Fourth, appellees argue that the legislature could have

swapped two reliably Democratic Greensboro precincts

outside District 12 (11 and 14) for four reliably Republican

High Point precincts (1, 13, 15, and 19) placed within

District 12. See ibid. The swap would not have improved

racial balance significantly, however, for each of the six

precincts have an African-American population of less

than 35%. Additionally, it too would have altered the

shape of District 12 for the worse. See Appendix D, infra;

see also App. 622 (testimony of Gerry Cohen). And, in any

event, the decision to exclude the two Greensboro pre-

cincts seems to reflect the legislature’s decision to draw

boundaries that follow main thoroughfares in Guilford

County. App. to Juris. Statement 205a; App. 575.

Even if our judgments in respect to a few of these pre-

22 HUNT v. CROMARTIE

Opinion of the Court

cincts are wrong, a showing that the legislature might

have “swapped” a handful of precincts out of a total of 154

precincts, involving a population of a few hundred out of a

total population of about half a million, cannot signifi-

cantly strengthen appellees’ case.

IV

We concede the record contains a modicum of evidence

offering support for the District Court’s conclusion. That

evidence includes the Cohen e-mail, Senator Cooper's

reference to “racial balance,” and to a minor degree, some

aspects of Dr. Weber's testimony. The evidence taken

together, however, does not show that racial considera-

tions predominated in the drawing of District 12’s bounda-

ries. That is because race in this case correlates closely

with political behavior. The basic question is whether the

legislature drew District 12's boundaries because of race

rather than because of political behavior (coupled with

traditional, nonracial districting considerations). It is not,

as the dissent contends, see post, at 9, whether a legisla-

ture may defend its districting decisions based on a

“stereotype” about African-American voting behavior. And

given the fact that the party attacking the legislature’s

decision bears the burden of proving that racial considera-

tions are “dominant and controlling,” Miller, 515 U. S., at

913, given the “demanding” nature of that burden of proof,

id., at 929 (O'CONNOR, J., concurring), and given the

sensitivity, the “extraordinary caution,” that district

courts must show to avoid treading upon legislative pre-

rogatives, id., at 916 (majority opinion), the attacking

party has not successfully shown that race, rather than

politics, predominantly accounts for the result. The record

leaves us with the “definite and firm conviction,” United

States Gypsum Co., 333 U. S., at 395, that the District

Court erred in finding to the contrary. And we do not

believe that providing appellees a further opportunity to

& *

Cite as: 532 U. S. (2001) 23

Opinion of the Court

make their “precinct swapping” arguments in the District

Court could change this result.

We can put the matter more generally as follows: In a

case such as this one where majority-minority districts (or

the approximate equivalent) are at issue and where racial

identification correlates highly with political affiliation,

the party attacking the legislatively drawn boundaries

must show at the least that the legislature could have

achieved its legitimate political objectives in alternative

ways that are comparably consistent with traditional

districting principles. That party must also show that

those districting alternatives would have brought about

significantly greater racial balance. Appellees failed to

make any such showing here. We conclude that the Dis-

trict Court's contrary findings are clearly erroneous.

Because of this disposition, we need not address appel-

lants’ alternative grounds for reversal.

The judgment of the District Court is

Reversed.

[Appendixes containing maps from appellees’ and appel-

lants’ briefs follow this page.]

4 APPENDIX A ® ®

Republican Victories in Forsyth County for All Precincts

Legend

STTT—— Counties

Precincts

97 Congressional District 12

3 Republican Victories

kes

I) Republican Victories

1 Republican Victory

0 Republican Victories

N.C. General Assembly,

| Information Systems Division

Source: App. to Brief for Appellees 2a.

® APPENDIX B

Republican Victories in Guilford County for All Precincts

Legend

Counties Precincts

97 Congressional District 12

Ly 3 Republican Victories

2 Republican Victories

pi 1 Republican Victory

Ue 0 Republican Victories

N.C. General Assembly,

Information Systems Division

Source: App. to Brief for Appellees 3a.

4 APPENDIX C "

Republican Victories in Mecklenburg County for All Precincts

Legend

Counties

Precincts

97 Congressional District 12

3 Republican Victories

2 Republican Victories

1 Republican Victory

0 Republican Victories 1

°

)

|

Aa

n

N.C. General Assembly,

Information Systems Division

Source: App. to Brief for Appellees 4a.

APPENDIX D _ % :

J North Center Grove North Monroe

Rig a ay EFFECT OF APPELLEES’ ——— ne Bilas We alo i Rt

Da en SWaps fi os t South Center od

BETWEEN HIGH POINT ounty a

AND GREENSBORO | He ale oy iy

PRECINCTS re fee

3

LEGEND a Friendship-1 i

—— County Lines "adil i |

——— Precinct Lines \ aS ees

BEER District Line nt ;

WE Precincts moved aE) ] ;

into District 12 at 2 gears r SU

Ee 7 Precinct d : = me

out of District 12 : a

Pg <\

| pT

South Jefferson |

HP-24 VE

ft

| |

al

Lomi Sumner

|

al

South Sumner Fentress-1

i

g bo

N

a

pS

i

]

I

J

LA

| 1 | Fe

i bn

,

Source: App. to Reply Brief for State Appellants 1a.

Cite as: 532 U. S. (2001) 1

THOMAS, J., dissenting

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

Nos. 99-1864 and 99-1865

JAMES B. HUNT, Jr., GOVERNOR OF NORTH

CAROLINA, ET AL., APPELLANTS

99-1864 v.

MARTIN CROMARTIE ET AL.

ALFRED SMALLWOOD, ET AL., APPELLANTS

99-1865 .

MARTIN CROMARTIE ET AL.

ON APPEALS FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR

THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF NORTH CAROLINA

[April 18, 2001]

JUSTICE THOMAS, with whom THE CHIEF JUSTICE,

JUSTICE SCALIA, and JUSTICE KENNEDY join, dissenting.

The issue for the District Court was whether racial

considerations were predominant in the design of North

Carolina’s Congressional District 12. The issue for this

Court is simply whether the District Court's factual find-

ing—that racial considerations did predominate—was

clearly erroneous. Because I do not believe the court

below committed clear error, I respectfully dissent.

I

The District Court's conclusion that race was the pre-

dominant factor motivating the North Carolina Legisla-

ture is a factual finding. See Hunt v. Cromartie, 526 U. S.

541, 549 (1999); Lawyer v. Department of Justice, 521

U. S. 567, 580 (1997); Shaw v. Hunt, 517 U.S. 899, 905

(1996); Miller v. Johnson, 515 U. S. 900, 910 (1995). See

also Anderson v. Bessemer City, 470 U. S. 564, 573 (1985)

(“[Intentional discrimination is a finding of fact ...”).

HUNT v. CROMARTIE

THOMAS, J., dissenting

Accordingly, we should not overturn the District Court’s

determination unless it is clearly erroneous. See Lawyer,

supra, at 580; Shaw, supra, at 910; Miller, supra, at 917.

We are not permitted to reverse the court’s finding “simply

because [we are] convinced that [we] would have decided

the case differently.” Anderson, supra, at 573. “Where

there are two permissible views of the evidence, the fact-

finder’s choice between them cannot be clearly erroneous.”

470 U.S., at 574. We should upset the District Court's

finding only if we are “‘left with the definite and firm

conviction that a mistake has been committed.”” Id., at

573 (quoting United States v. United States Gypsum Co.,

333 U. S. 364, 395 (1948)).

The Court does cite cases that address the correct stan-

dard of review, see ante, at 7, and does couch its conclu-

sion in “clearly erroneous” terms, see ante, at 22-23. But

these incantations of the correct standard are empty ges-

tures, contradicted by the Court’s conclusion that it must

engage in “extensive review.” See ante, at 7. In several

ways, the Court ignores its role as a reviewing court and

engages in its own factfinding enterprise.! First, the

Court suggests that there is some significance to the ab-

sence of an intermediate court in this action. See ibid.

This cannot be a legitimate consideration. If it were le-

gitimate, we would have mentioned it in prior redistricting

cases. After all, in Miller and Shaw, we also did not have

the benefit of intermediate appellate review. See also

1Despite its citation of Bose Corp. v. Consumers Union of United

States, Inc., 466 U. S. 485 (1984), ante, at 7, I do not read the Court's

opinion to suggest that the predominant factor inquiry, like the actual

malice inquiry in Bose, should be reviewed de novo because it is a

“constitutional fac[t].” 466 U.S., at 515 (REHNQUIST, J., dissenting).

Nor could it, given our holdings in Lawyer v. Department of Justice, 521

U. S. 567 (1997), Miller v. Johnson, 515 U. S. 900 (1995), and Shaw v.

Hunt, 517 U. S. 899 (1996).

Cite as: 532 U.S. (2001) 3

THOMAS, J., dissenting

United States v. Oregon State Medical Soc., 343 U. S. 326,

330, 332 (1952) (engaging in clear error review of factual

findings in a Sherman Act case where there was no inter-

mediate appellate review). In these cases, we stated that

the standard was simply “clearly erroneous.” Moreover,

the implication of the Court's argument is that intermedi-

ate courts, because they are the first reviewers of the

factfinder’s conclusions, should engage in a level of review

more rigorous than clear error review. This suggestion is

not supported by law. See Fed. Rule Civ. Proc. 52(a)

(“Findings of fact, whether based on oral or documentary

evidence, shall not be set aside unless clearly erroneous

7). In fact, the very case the Court cited to articulate

clear error review discussed the standard as it applied to

an intermediate appellate court, which obviously did not

have the benefit of another layer of review. See ante, at 7

(citing Anderson, supra, at 573).

Second, the Court appears to discount clear error review

here because the trial was “not lengthy.” Ante, at 7. Even

if considerations such as the length of the trial were rele-

vant in deciding how to review factual findings, an as-

sumption about which I have my doubts,? these considera-

tions would not counsel against deference in this action.

The trial was not “just a few hours” long, Bose Corp. v.

Consumers Union of United States, Inc., 466 U. S. 485, 500

2 Bose, which the Court cites to support its discounting of clear error

review, ante, at 7, does state that “the likelihood that the appellate

court will rely on the presumption [of correctness of factual findings]

tends to increase when trial judges have lived with the controversy for

weeks or months instead of just a few hours.” 466 U. S., at 500. It is

unclear, however, what bearing this statement of fact—that appellate

courts will defer to factual findings more often when the trial was

long—had on our understanding of the scope of clear error review. In

Bose, we held that a lower court’s “actual malice” finding must be

reviewed de novo, see id., at 514, not that clear error review must be

calibrated to the length of trial.

4 HUNT uv. CROMARTIE

THOMAS, J., dissenting

(1984); it lasted for three days in which the court heard

the testimony of 12 witnesses. And quite apart from the

total trial time, the District Court sifted through hundreds

of pages of deposition testimony and expert analysis,

including statistical analysis. It also should not be forgot-

ten that one member of the panel has reviewed the itera-

tions of District 12 since 1992. If one were to calibrate

clear error review according to the trier of fact’s familiar-

ity with the case, there is simply no question that the

court here gained a working knowledge of the facts of this

litigation in myriad ways over a period far longer than

three days.

Third, the Court downplays deference to the District

Court’s finding by highlighting that the key evidence was

expert testimony requiring no traditional credibility de-

terminations. See ante, at 7. As a factual matter, the

Court overlooks the District Court’s express assessment of

the legislative redistricting leader’s credibility. See App.

to Juris. Statement in No. 99-1864, pp. 27a, 28a, n. 8. It

is also likely that the court’s interpretation of the e-mail

written by Gerry Cohen, the primary drafter of District 12,

was influenced by its evaluation of Cohen as a witness.

See id., at 28a, n. 8. See also App. 261-268. And, as a

legal matter, the Court's emphasis on the technical nature

of the evidence misses the mark. Although we have rec-

ognized that particular weight should be given to a trial

court’s credibility determinations, we have never held that

factual findings based on documentary evidence and ex-

pert testimony justify “extensive review,” ante, at 7. On

the contrary, we explained in Anderson that “[t]he ration-

ale for deference . . . is not limited to the superiority of the

trial judge’s position to make determinations of credibil-

ity.” 470 U. S., at 574. See also Fed. Rule Civ. Proc. 52(a)

(specifically referring to oral and documentary evidence).

Instead, the rationale for deference extends to all deter-

minations of fact because of the trial judge's “expertise” in

4

Cite as: 532 U.S. (2001) 5

THOMAS, J., dissenting

making such determinations. 470 U. S., at 574. Accord-

ingly, deference to the factfinder “is the rule, not the ex-

ception,” id., at 575, and I see no reason to depart from

this rule in the case before us now.

Finally, perhaps the best evidence that the Court has

emptied clear error review of meaningful content in the

redistricting context (and the strongest testament to the

fact that the District Court was dealing with a complex

fact pattern) is the Court’s foray into the minutiae of the

record. I do not doubt this Court’s ability to sift through

volumes of facts or to argue its interpretation of those

facts persuasively. But I do doubt the wisdom, efficiency,

increased accuracy, and legitimacy of an extensive review

that is any more searching than clear error review. See

id., 574-575 (“Duplication of the trial judge's efforts . . .

would very likely contribute only negligibly to the accu-

racy of fact determination at a huge cost in diversion of

judicial resources”). Thus, I would follow our precedents

and simply review the District Court's finding for clear

error.

II

Reviewing for clear error, I cannot say that the District

Court's view of the evidence was impermissible.? First,

the court relied on objective measures of compactness,

which show that District 12 is the most geographically

scattered district in North Carolina, to support its conclu-

sion that the district’s design was not dictated by tradi-

tional districting concerns. App. to Juris. Statement in

3] assume, because the District Court did, that the goal of protecting

incumbents is legitimate, even where, as here, individuals are incum-

bents by virtue of their election in an unconstitutional racially gerry-

mandered district. No doubt this assumption is a questionable proposi-

tion. Because the issue was not presented in this action, however, I do

not read the Court’s opinion as addressing it.

6 HUNT v. CROMARTIE

THOMAS, J., dissenting

No. 99-1864, p. 26a. Although this evidence was available

when we held that summary judgment was inappropriate,

we certainly did not hold that it was irrelevant in deter-

mining whether racial gerrymandering occurred. On the

contrary, we determined that there was a triable issue of

fact. Moreover, although we acknowledged “that a dis-

trict’s unusual shape can give rise to an inference of politi-

cal motivation,” we “doubt[ed] that a bizarre shape equally

supports a political inference and a racial one.” Hunt, 526

U. S., at 547, n. 3. As we explained, “[s]Jome districts . . .

are ‘so highly irregular that [they] rationally cannot be

understood as anything other than an effort to segregat[e]

... voters’ on the basis of race.” Ibid. (internal quotation

marks omitted).

Second, the court relied on the expert opinion of Dr.

Weber, who interpreted statistical data to conclude that

there were Democratic precincts with low black popula-

tions excluded from District 12, which would have created

a more compact district had they been included.# App. to

Juris. Statement in No. 99-1864, p. 25a. And contrary to

the Court’s assertion, Dr. Weber did not merely examine

the registration data in reaching his conclusions. Dr.

Weber explained that he refocused his analysis on per-

formance. He did so in response to our concerns, when we

reversed the District Court’s summary judgment finding,

that voter registration might not be the best measure of

the Democratic nature of a precinct. See id., at 26a (citing

4] do not think it necessary to impose a new burden on appellees to

show that districting alternatives would have brought about “signifi-

cantly greater racial balance.” Ante, at 22. I cannot say that it was

impermissible for the court to conclude that race predominated in this

action even if only a slightly better district could be drawn absent racial

considerations. The District Court may reasonably have found that

racial motivations predominated in selecting one alternative over

another even if the net effect on racial balance was not “significant.”

Cite as: 532 U.S. (2001) 7

THOMAS, J., dissenting

Trial Tr., which appears at App. 90-92, 105-107, 156—

157). This fact was not lost on the District Court, which

specifically referred to those pages of the record covering

Dr. Weber's analysis of performance.

Third, the court credited Dr. Weber's testimony that the

districting decisions could not be explained by political

motives. App. to Juris. Statement in No. 99-1864, p. 26a.

In the first instance, I, like the Court, ante, at 11, might

well have concluded that District 12 was not significantly

“safer” than several other districts in North Carolina

merely because its Democratic reliability exceeded the

optimum by only 3 percent. And I might have concluded

that it would make political sense for incumbents to adopt

a “the more reliable the better” policy in districting. How-

ever, I certainly cannot say that the court’s inference from

the facts was impermissible.®

5Dr. Weber admitted that, when he first concluded that race was the

motivating factor, he was under the mistaken impression that the

legislature’s computer program provided only racial, not political, data.

The Court finds that this admission undercut the validity of Dr.

Weber's conclusions. See ibid. Although the District Court could have

found that this impression was a sufficiently significant assumption in

Dr. Weber's analysis that the conclusions drawn from the analysis were

suspect, it was not required to do so as a matter of logic. The court

reasonably could have believed that the false impression had very little

to do with the statistical analysis that was largely responsible for Dr.

Weber's conclusions.

In addition, the Court discounts Dr. Weber's testimony because he

“express[ed] disdain for a process that we have cautioned courts to

respect,” ibid. Dr. Weber did openly state that he believes that the best

districts he had seen in the 1990's were those drawn by judges, not by

legislatures. App. 150-151. However, whether Dr. Weber was simply

stating the conclusions he has reached through his experience or was

expressing a feeling of contempt toward the legislature is precisely the

kind of tone, demeanor, and bias determination that even the Court

acknowledges should be left to the factfinder, cf. ante, at 7.

6The Court also criticizes Dr. Weber's testimony that Precinct 77's

split was racially motivated and his proposed alternative that all of

HUNT v. CROMARTIE

THOMAS, J., dissenting

Fourth, the court discredited the testimony of the

State’s witness, Dr. Peterson. App. to Juris. Statement in

No. 99-1864, p. 27a (explaining that Dr. Weber testified

that Dr. Peterson’s analysis “ignor[ed] the core,” “ha[d] not

been appropriately done,” and was “unreliable”). Again,

like the Court, if I were a district court judge, I might have

found that Dr. Weber's insistence that one could not ig-

nore the core was unpersuasive.” However, even if the

core could be ignored, it seems to me that Dr. Weber's

testimony—that Dr. Peterson had failed to analyze all of

the segments and thus that his analysis was incomplete,

App. 119-120—reasonably could have supported the

court’s conclusion.

Finally, the court found that other evidence demon-

strated that race was foremost on the legislative agenda:

an e-mail from the drafter of the 1992 and 1997 plans to

senators in charge of legislative redistricting, the com-

puter capability to draw the district by race, and state-

Precinct 77 could have been moved into District 9. Apparently the

Court believes that it is obvious that the Republican incumbent in

District 9 would not have wanted the whole of Precinct 77 in her

district. See ante, at 12-13. But the Court addresses only part of Dr.

Weber's alternative of how the districts could have been drawn in a

race-neutral fashion. Dr. Weber explained that the alternative was not

simply to move Precinct 77 into District 9. The alternative would also

include moving other reliably Democratic precincts out of District 9 and

into District 12, which presumably would have satisfied the incumbent.

App. 157. This move would have had the result, not only of keeping

Precinct 77 intact, but also of widening the corridor between the east-

ern and western portions of District 9 and thereby increasing the

functional contiguity. The Court’s other criticism, that moving all of

Precinct 77 into District 12 would not work, is simply a red herring.

Dr. Weber talked only of moving all of Precinct 77 into District 9, not of

moving all of Precinct 77 into District 12.

70Of course, considering that District 12 has never been constitution-

ally drawn, Dr. Weber's criticism—that the problem with the district

lies not just at its edges, but at its core—is not without force.