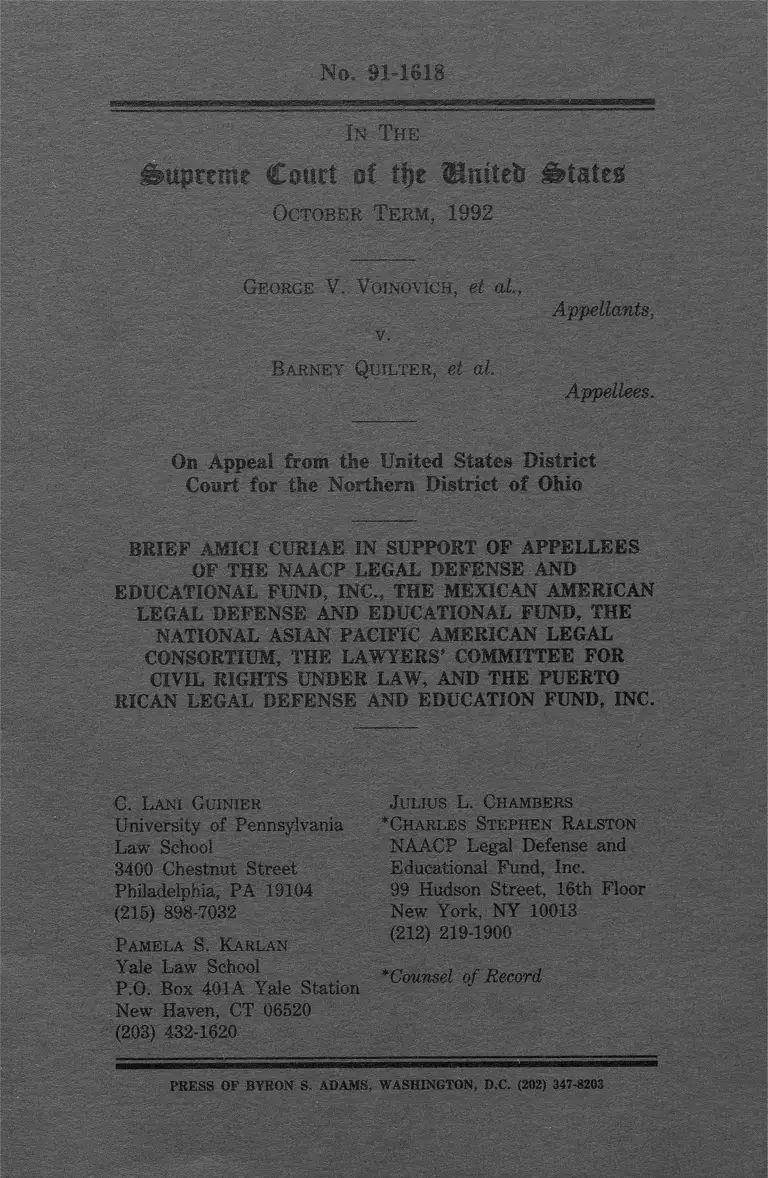

Voinovich v. Quilter Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Appellees

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1992

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Voinovich v. Quilter Brief Amici Curiae in Support of Appellees, 1992. 21719c1c-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/55de0cd4-846c-411a-9e37-0371de036e7a/voinovich-v-quilter-brief-amici-curiae-in-support-of-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

No. 91-1818

In The

Jkiptemc Court of t|}t Bmtefe States!

October Term , 1992

George Y. Voingvich, ei at.,

Appellants,

v.

Barney Quilter, et al.

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District

Court for the Northern District of Ohio

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES

OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., THE MEXICAN AMERICAN

LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, THE

NATIONAL ASIAN PACIFIC AMERICAN LEGAL

CONSORTIUM, THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW, AND THE PUERTO

RICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATION FUND, INC.

C. Lani Guinier

University of Pennsylvania

Law School

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, PA 13104

(215) 838-7032

Pamela S. Karlan

Yale Law School

P.O. Box 401A Yale Station

New Haven, CT 06520

(203) 432-1620

Julius L. Chambers

’Charles Stephen Ralston

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

* Counsel of Record

PRESS OF BYRON S. ADAMS, WASHINGTON, D.C. (202) 347-8203

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................. i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ......... iii

INTEREST OF AMICI C U R IA E ............................................ 1

Summary of Ar g u m e n t ........................................... 4

Argument ................................................................... 6

I. The Challenged Plan violated

THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT’S

Requirement of One-Person,

One-Vo t e ............................................. 6

A. The Analytic Framework for

E va lu a tin g C laim s o f

Quantitative Vote Dilution . . . . 7

1. Proof of a Prima Facie

Case ................................. 7

2. Identification of a

Serious State Interest

S e r v e d by t h e

Deviation ........................ 8

3. Proof of a Close "Fit"

Between Deviation and

P olicy ............................... 9

B. The Failure of the Challenged

P la n ............................................ 10

11

II The District Court’s Analysis

of the Claim of Racial Vote

Dilution Was Fatally Flawed . . 12

A. The Voting Rights Act Did Not

Require the Apportionment

Board to Use a Particular

Analytic Framework as a

P r e r e q u i s i t e f o r

Reapportionment........................ 14

B. The District Court Itself Failed

to Comply With Section 2 ’s

Requirements............................... 17

C. The District Court’s Holding

on P la in tiffs’ Fifteenth

Am endm ent Claim was

Unsupport able ................. 21

Conclusion 23

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Pages:

Abate v. Mundt, 403 U.S. 182 (1971)................... 8, 11

Brown v. Thompson, 462 U.S. 835 (1983)......... 4, 7-12

Chapman v. Meier, 420 U.S. 1 (1975) ........................9

Chisom v. Roemer, 111 S.Ct. 2354 (1991)................... 2

City of Lockhart v. United States, 460 U.S. 125 (1983) 2

City of Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980) .......... 19

Clark v. Roemer, 111 S.Ct. 2096 (1991) ....................... 3

Connor v. Finch, 401 U.S. 407 (1977)........................ 13

Connor v. Finch, 431 U.S. 407 (1977).......................... 3

Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U.S. 735 (1973) . . . 7, 15, 16

Garza v. County of Los Angeles, 756 F. Supp. 1298

(C.D. Cal.), aff’d, 918 F.2d 763 (9th Cir. 1990),

cert, denied, 498 U .S .__ , 111 S.Ct. 681, 112

L.Ed.2d 673 (1 991 )................................................ 2

Gingles v. Edmisten, 590 F.Supp. 345 (E.D.N.C. 1984),

aff’d 478 U.S. 30 (1986)............................ 19, 20

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960) ............ 22

Hastert v. State Board of Elections, 777 F. Supp. 634

(N.D. 111. 1991)....................................................... 2

IV

Pages:

Houston Lawyers Ass’n v. Attorney General of Texas,

111 S.Ct. 2376 (1991) .........................................2

Jeffers v. Clinton, 730 F. Supp. 196 (E.D. Ark. 1989),

summarily aff’d, 111 S.Ct. 662 (1991) ............ 19

Kilgarlin v. Hill, 386 U.S. 120 (1967) .......................... 9

Mahan v. Howell, 410 U.S. 315 (1973)................... 8-11

NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963) ................... . 2

Nevitt v. Sides, 571 F.2d 209 (5th Cir. 1978).............. 6

Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964) . . 4, 6-8, 11, 15

Rogers v. Lodge, 458 U.S. 613 (1982)................. 18, 22

Smith v. Clinton, 488 U.S. 988 (1988).......................... 3

Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30 (1986)......... passim

United Jewish Organizations v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144

(1977) ............................................................ 2, 15

Voinovich v. Ferguson, 586 N.E.2d 1020, (Ohio 1992) 12

Washington v. Yakima Indian Nation, 439 U.S. 463

(1979) ................................................................... 4

White v. Weiser, 412 U.S. 783 (1973)........................ 13

Wilson v. Eu, 823 P.2d 545 (Cal. 1992) ......................2

Pages:

Statutes: Pages:

Ohio Const, art. XI, § 9 ........................................ .. . 10

Voting Rights Act of 1965 ........................ 4-6, 14-17, 20

Other Authorities: Pages:

Daniel R. Ortiz, Federalism, Reapportionment, and

Incumbency: Leading the Legislature to Police

Itself, 4 J.L. & Pol. 653 (1 9 8 8 )....................... 13

S. Rep. No. 97-417 (1982)........................................ 16-20

V

N o. 91-1618

In The

Supreme Court of tfje Umteb States;

October Term, 1992

George V. Voinovich, et al.,

Appellants,

v.

Barney Quilter, et al.

Appellees

On Appeal from the United States District Court for

the Northern District of Ohio

BRIEF AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF APPELLEES OF

THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC., THE MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, THE NATIONAL

ASIAN PACIFIC AMERICAN LEGAL CONSORTIUM, THE

LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER

LAW, AND THE PUERTO RICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATION FUND, INC.

Interest of Amici Curiae*

The NAlACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

("the Fund") is a non-profit corporation that was

’ Letters consenting to the filing of this brief have been filed

with the Clerk of Court.

2

established for the purpose of assisting black citizens in

securing the constitutional and civil rights. This Court has

noted the Fund’s "reputation for expertness in presenting

and arguing the difficult questions of law that frequently

arise in civil rights litigation." NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S.

415, 422 (1963). The Fund has participated in many of

the significant constitutional and statutory voting rights

cases in this Court. See, e.g., Houston Lawyers Ass’n v.

Attorney General of Texas, 111 S.Ct. 2376 (1991); Chisom

v. Roemer, 111 S.Ct. 2354 (1991); Thornburg v. Gingles,

478 U.S. 30 (1986); United Jewish Organizations v. Carey,

430 U.S. 144 (1977).

The Mexican American Legal Defense and

Educational Fund ("MALDEF") is a non-profit national

civil rights organization headquartered in Los Angeles.

Its principal objective is to secure, through litigation and

education, the civil rights of Hispanics living in the United

States. Because of the importance of the fundamental

right to vote, MALDEF has represented Hispanic voters

in numerous voting rights cases, has frequently appeared

before this Court in such cases, see, e.g, City of Lockhan

v. United States, 460 U.S. 125 (1983), has challenged the

redistricting of the most populous local jurisdiction in the

country, see Garza v. County of Los Angeles, 756 F. Supp.

1298 (C.D. Cal.), aff’d, 918 F.2d 763 (9th Cir. 1990), cert.

denied, 498 U.S. ___, 111 S.Ct. 681, 112 L.Ed.2d 673

(1991), and has been intensely involved in redistricting

advocacy following the 1990 census, see, e.g, Hasten v.

State Board of Elections, 111 F. Supp. 634 (N.D. 111.

1991) (three-judge court); Wilson v. Eu, 823 P.2d 545 (Cal.

1992) .

The National Asian Pacific American Legal

Consortium ("NALPAC") is a nonprofit organization

whose mission is to advance the legal and civil rights of

3

Asian Pacific Americans through a national collaborative

structure that pursues litigation, advocacy, education, and

public policy development. The NALPAC is composed of

three civil rights organizations that have advocated for the

voting rights of Asian Pacific Americans: the Asian

American Legal Defense and Education Fund (New

York)s, the Asian Law Caucus, Inc. (San Francisco), and

the Asian Pacific America Legal Center of Southern

California (Los Angeles). All three members of the

NALPAC have promoted the political empowerment of

Asian Pacific Americans through litigation, legislative

advocacy, and participation in state and local redistricting

efforts.

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

was organized in 1963 at the request of the President of

the United States to involve private attorneys throughout

the country in the national effort to assure civil rights to

all Americans. Protection of the voting rights of citizens

is an important part of the Committee’s work. The

Lawyers’ Committee has represented black citizens in

reapportionment before this Court in several cases

including Connor v. Finch, 431 U.S. 407 (1977), and Smith

v. Clinton, 488 U.S. 988 (1988), and has appeared in

numerous other significant voting rights cases in this

Court. See, e.g., Clark v. Roemer, 111 S.Ct. 2096 (1991).

The Puerto Rican Legal Defense and Education

Fund, Inc. ("PRLDEF") is a national civil rights

organization founded in 1972 to protect the civil rights of

Puerto Ricans and other Latinos, and to ensure their

equal protection under the law. Since its inception,

PRLDEF has worked to politically empower the Puerto

Rican and Latino communities. Barriers to Latino

political participation have been lifted, and voting rights

violations have been successfully challenged by PRLDEF

4

in the courts and before the United States Department of

Justice. PRLDEF is currently working to ensure an equal

opportunity for Puerto Ricans and other Latinos in the

redistricting process, which is, and has been, occurring

throughout the country as a consequence of the decennial

census.

Su m m a r y o f a r g u m e n t

The district court’s opinions in this case

fundamentally misunderstand the Voting Rights Act of

1965 and the Fifteenth Amendment. Reapportionment is

an inherently political process, and this Court has

authorized judicial intervention only when the process

results in a plan that violates a federal constitutional or

statutory provision.

Nonetheless, the judgment below should be affirmed

because the challenged plan violated the principles of

equipopulous districting laid out by this Court in Reynolds

v. Sims, 377 U.S. 533 (1964), and its progeny.1 Once a

constitutionally significant deviation in population among

districts has been shown, the State bears the burden of

justifying the deviation. In challenges to state legislative

apportionments, this burden is triggered by a total

population deviation of more than ten percent. Brown v.

Thompson, 462 U.S. 835 (1983). In this case, it is

1 Under Washington v. Yakima Indian Nation, 439 U.S. 463, 476

n. 20 (1979), appellees, and thus amici supporting them, can defend

the judgment "on any ground properly raised below, whether or not

that ground was relied upon, rejected, or even considered by the

District Court ...." We urge the Court to affirm solely on the narrow,

albeit constitutional ground, that appellants failed to meet their

burden of proof with regard to the one-person, one-vote issue.

5

undisputed that the challenged plan had a deviation of

nearly thirteen percent. Nonetheless, appellants

[hereafter the Apportionment Board] provided no

evidence to substantiate their claim that the deviation was

justifiable. In fact, at least a portion of the deviation was

on its face unrelated to the professed state policy. Since

the Apportionment Board failed to meet its burden of

justifying an otherwise-unconstitutional deviation, the

challenged plan must be invalidated.

But while the District Court correctly held that the

Plan violated the Fourteenth Amendment on one-person,

one-vote grounds, the remainder of its analysis was

seriously flawed. To ensure that judicial invalidation of a

plan developed and adopted by a state’s political branches

is warranted, Congress and this Court have required

district courts to engage in an intensely local appraisal of

the design and impact of a challenged plan, and to make

detailed findings of fact. Thornburg v. Gingles and the

Senate Report accompanying the 1982 amendments to the

Voting Rights Act delineate a range of relevant factors

for courts to consider.

But because state political entities, unlike federal

courts, have inherent authority to engage in

reapportionment, they are simply not subject to the same

procedural and factfinding constraints. States are free to

devise a variety of reapportionment processes and to

select from among a virtually infinite array of

constitutionally and statutorily acceptable plans.

In this case, the district court turned these well-

developed principles upside down. It required state

political actors to follow the Gmgte-Senate Report

framework as a prerequisite to adopting a plan but it

completely disregarded the framework as a prerequisite to

6

its own action in judicially invalidating the plan. The

court below struck down Ohio’s reapportionment plan

[hereafter "the Plan"] without identifying any facts that

would justify finding either a constitutional or a statutory

violation. Because the district court never found that

plaintiffs would suffer any cognizable injury as a result of

the challenged plan — indeed, plaintiffs’ theory of the case

was self-contradictory — it erred in striking down the plan

as violative of the Voting Rights Act. Moreover, the

district court’s treatment of the Fifteenth Amendment

issue was shockingly offhanded: it simply asserted, without

any discussion of underlying facts, that the plan was

intentionally discriminatory.

A r g u m e n t

I. T h e C h a l l e n g e d P l a n V io l a t e d t h e

F o u r t e e n t h A m e n d m e n t ’s R e q u ir e m e n t o f

O n e -P e r s o n , O n e -V o t e

The central command of the equal protection clause

with respect to state legislative apportionment is clear: the

"basic constitutional standard" of one-person, one-vote

requires a State to "make an honest and good faith effort

to construct districts, in both houses of its legislature, as

nearly of equal population as is practicable." Reynolds v.

Sims, 377 U.S. 533, 568, 577 (1964). If districts are

malapportioned, the ballots cast by voters in heavily

populated districts will be devalued relative to the votes

cast by individuals in less-populated districts. This form

of vote dilution is characterized as quantitative because it

is based on mathematical comparisons of various district

sizes. Nevitt v. Sides, 571 F.2d 209, 215 (5th Cir. 1978).

7

In response to the two -post-Reynolds rounds of

reapportionment activity, this Court has set out a clear

analytic framework for assessing claims of quantitative

vote dilution. In this case, application of the framework

shows that the challenged plan failed to pass muster

under the equal protection clause.

A. The Analytic Framework for Evaluating Claims of

Quantitative Vote Dilution

Because the right to vote is so fundamental to the

governance of a democratic society, "any alleged

infringement ... must be carefully and meticulously

scrutinized." Reynolds, 377 U.S. at 562. Accordingly,

once a plaintiff has made a prima facie showing of

constitutionally significant population deviation, the State

bears a heavy justificatory burden. This Court’s decisions

provide a three-step process for assessing this question.

1. Proof o f a Prima Facie Case

The first step is to ask whether there is a

constitutionally significant deviation in population among

districts. In the context of state legislative

reapportionment, this Court has squarely held that a total

deviation of ten percent establishes a prima facie case.

See Brown v. Thompson, 462 U.S. 835, 843 (1983); White

v. Regester, 412 U.S. 755, 764 (1973). The plaintiffs bear

the burden of proof on this issue, and if they fail to satisfy

this "threshold requirement," their claim must be

dismissed. See id. (deviation of 9.9% fails to meet

threshold); Gaffney v. Cummings, 412 U.S. 735, 750-51

(1973) (deviation of 7.83% fails to meet threshold).

8

Once plaintiffs have established a prima facie case,

however, the burden shifts: Constitutionally significant

deviations "must be justified by the State." Brown v.

Thompson, 462 U.S. at 843. If the State fails to provide

a sufficient justification, then the challenged plan must be

invalidated.

2. Identification of a Serious State Interest

Served by the Deviation

The second step of the process asks whether the

challenged plan furthers a rational, legitimate state policy.

See, e.g., Brown v. Thompson, 462 U.S. at 843-44; Mahan

v. Howell, 410 U.S. 315, 324-26 (1973); Abate v. Mundt,

403 U.S. 182, 185-86 (-1971); Reynolds, 377 U.S. at 577-81.

Here, the State bears the burden of proof. And it is not

enough simply to identify a potentially legitimate policy.

Rather, the State must show why its "particular

circumstances and needs," Abate v. Mundt, 403 U.S. at

185, justify more than the constitutionally de minimis

variations already accounted for by the ten percent

threshold.

That this second step requires an intensely local

appraisal of the basis for the deviation can be seen from

this Court’s painstaking discussion of the particular

governmental schemes at issue in previous one-person,

one-vote cases. Although the Court has stated that

preservation of subdivision boundaries may allow some

deviation, see, e.g, Brown v. Thompson, 462 U.S. at 843-

44; Mahan v. Howell, 410 U.S. at 325-27; Reynolds, 377

U.S. at 580-81, it has been equally clear that prior cases

provide no blanket license for departures from

equipopulous districting. In Abate v. Mundt, for example,

the Court emphasized the fact that the same individuals

occupied the governing positions both in the county

9

legislature and on the boards of supervisors of the

constituent political subdivisions to justify an 11.9 percent

total deviation that it would otherwise have been "hesitant

to accept Id. at 186. Similarly, in Mahan v. Howell,

the Court pointed to the distinctive role of the Virginia

General Assembly in enacting local legislation as a reason

for upholding a plan whose 16.4 percent total deviation

came close to "approach[ing] tolerable limits," 410 U.S. at

329. Finally, in Brown v. Thompson, the Court found a

policy of giving each county its own representative had

"particular force, given the peculiar size and population of

the State [of Wyoming] and the nature of its

governmental structure." 462 U.S. at 844. Of special

significance to the present case, some Wyoming counties

were so much smaller than an ideal district that their

interests as counties would be totally submerged if they

were combined with other counties to form equipopulous

districts. See id. at 841 n. 5. In short, in each case, the

Court has required a showing that the articulated policy

was rational and legitimate in light of the State’s

particular governmental structure.

3. Proof of a Close "Fit" Between Deviation and

Policy

The third step requires the State to show a close

degree of "fit" between the actual deviations created by

the challenged plan and the permissible state policy. It

must show that the deviations incurred under its plan are

necessary to the achievement of that policy. Compare, e.g.,

Mahan v. Howell, 410 U.S. at 326 (approving plan because

it "produces the minimum deviation above and below the

norm" attainable), with Chapman v. Meier, 420 U.S. 1, 25

(1975) (invalidating plan, despite legitimacy of state

policy, because it was possible to achieve policy with plan

using a smaller deviation), and Kilgarlin v. Hill, 386 U.S.

10

120, 124 (1967) (per curiam) (same). If alternative plans

could achieve the State’s goal while more closely

complying with one-person, one-vote, then the deviation

is unjustified.

B. The Failure of the Challenged Plan

That the challenged Plan is prima facie

unconstitutional is clear. According to the 1990 census,

Ohio has a total population of 10,847,133. App. to Juris.

St. 49a. Since the Ohio House has 99 members, the ideal

House district size is 109,567. Id. at 21a. Under the Plan,

the smallest district, comprised solely of Ashtabula

County, had a population of 99,821, id. at 52a n. 11, or

91.10 percent of an ideal district. The largest district, one

of thirteen in Cuyahoga County, had a population of

114,955, id. at 56a, or 104.92 percent of an ideal district.

Thus, the total population deviation of the Plan was 13.82

percent, well over the ten percent threshold.2

2 Ohio law would have permitted up to a 20 percent total

deviation. See Ohio Const, art. XI, § 9 (requiring that "reasonable

effort shall be made to create a house of representatives district

consisting of the whole county" for any county that is at least 90

percent of the ideal district size and for any county that is not more

than 110 percent of the ideal district size). Such a deviation would

clearly raise serious questions: indeed, it is not clear that any

legitimate policy could justify it. See Mahan v. Howell, 410 U.S. at

329; cf. Brown v. Thompson, 462 U.S. at 850 (O’Connor, J.,

concurring); id. at 853-56 (Brennan, J., dissenting).

To the extent, however, that the- district court based its

invalidation of the 1992 Plan on the statutory authorization of a 20

percent total deviation, rather than on the actual deviation created,

see App. to Juris. St. 147a n. 12, it was mistaken: the real question in

a one-person, one-vote case is whether the challenged plan

unconstitutionally dilutes some citizens’ votes, not whether a another

11

In the face of this presumptively unconstitutional

malapportionment, the Apportionment Board has raised

only the most perfunctory defense: "Ohio’s longstanding

policy to reflect political subdivision boundaries where

reasonably possible." Juris. St. at 25. The Board has

provided no details about Ohio’s state or local

governmental structure that might justify elevating

artificial subdivision boundaries above a fundamental

constitutional command. A bare citation of Mahan v.

Howell and Brown v. Thompson cannot substitute for the

detailed description of "particular circumstances and

needs," Abate v. Mundt, 403 U.S. at 185, that this Court

has always required. Unless this Court is prepared to

abdicate completely its commitment in Reynolds to give

"careful judicial scrutiny" to claims regarding political

subdivision boundaries, 377 U.S. at 580-81, it simply

cannot countenance appellants’ desultory justification in

this case.

Moreover, regardless of the legitimacy of Ohio’s

purported policy, the Apportionment Board failed to show

that the deviations incurred under the Plan were entirely

necessary to the achievement of that policy. First, it

presented no evidence that the portion of the total

deviation attributable to the size of the most populous

district had anything to do with the purported policy.

While the smallest single district is a whole-county district,

the largest district is not. Rather, it is one of thirteen

Cuyahoga County districts. See App. to Juris. St. 56a.

Merely by redrawing districts entirely within Cuyahoga

County, the total deviation of the Plan could have been

reduced without any impairment whatsoever of the policy

hypothetical plan might do so.

12

of preserving subdivisions.3 Second, it is not altogether

clear, given the number of split-county districts adjacent

to Ashtabula County, see Voinovich v. Ferguson, 586

N.E.2d 1020, 1038-39 (Ohio 1992) (Resnick, J ,

dissenting), that portions of counties that were being split

among districts anyway could not have been added to the

Ashtabula-based district to bring it closer to the ideal

district size. Given that Ashtabula would still have

formed the vast majority of the district, it would have

enjoyed an effective voice as a subdivision. Cf Brown v.

Thompson, 462 U.S. at 841 n. 5 (where Niobrara County

was so small that it would be completely swamped in a

multi-county district, deviation needed to give it its own

district might be justified).

None of this is to say that it would have been

impossible for the Apportionment Board to justify the

deviations in the Plan. But the fact remains: it did not do

so. Accordingly, this Court should affirm the holding of

the district court that the Board "failjed] to provide

sufficient justification for1' a greater than ten percent total

deviation.

II. T h e D is t r ic t C o u r t ’s A n a l y s is o f

t h e C l a im o f R a c ia l V o t e D il u t io n

W a s F a t a l l y F l a w e d

"From the beginning," this Court has maintained that

"reapportionment is primarily a matter for legislative

3 Indeed, there is a substantial [9.2 percent] population deviation

among Cuyahoga County districts: the smallest has a population of

104,872, while the largest has a population of 114,955. App. to Juris.

St. 56a.

13

consideration and determination" and that "state

legislatures have primary jurisdiction over legislative

reapportionment." White v. Weiser, 412 U.S. 783, 794-95

(1973) (internal quotation marks omitted). Decisions

about how to organize the legislature and how to allocate

political power among competing groups lie at the very

heart of democratic self-governance. Judicial intervention

is warranted only when the normal, political — almost

inevitably partisan — process fails.

Thus, the State’s political agencies and the federal

judiciary operate under very different constraints when

they participate in the districting process. For example,

if a court is called upon to develop a districting system for

state offices, it must adhere far more closely to the one-

person, one-vote standard than would a state legislature:

a court must provide "some compelling justification" for

deviations that would not demand any justification

whatsoever were they created by a legislative plan. See,

e.g., Connor v. Finch, 401 U.S. 407, 416-21 (1977); see

generally Daniel R. Ortiz, Federalism, Reapportionment,

and Incumbency: Leading the Legislature to Police Itself, 4

J.L. & Pol. 653, 662-64 (1988).

In this case, the court below made two critical errors.

First, it imposed too onerous a standard on Ohio by

requiring the Apportionment Board to undertake a full

blown section 2 liability analysis as part of its

reapportionment process. Second, it improperly relaxed

the constraints upon itself by invalidating a democratically

created plan without undertaking any section 2 analysis at

all.

14

A. The Voting Rights Act Did Not Require the

Apportionment Board to Use a Particular Analytic

Framework as a Prerequisite for Reapportionment

In the district court’s January 31 opinion, the two

reasons given for invalidating Ohio’s Plan were that James

Tilling, the Plan’s architect, erroneously thought that the

Voting Rights Act required him to maximize the number

of districts with effective black voting majorities, see App.

to Juris. St. 8a-10a, and that Tilling failed to conduct an

adequate section 2 totality-of-the-circumstances analysis,

id. at lla-14a. Neither reason provides any basis for

enjoining the Plan.

First, Tilling’s opinion about the mandates of the

Voting Rights Act is entirely irrelevant to the question

whether the plan he produced passed muster under the

Act. Thus, this Court need not address the question

whether Ohio was compelled by the Voting Rights Act to

create a significant number of majority-black districts.

The only question properly before this Court is whether

the Voting Rights Act permitted Ohio to take that tack.

As to this, the answer is plainly affirmative. In United

Jewish Organizations v. Carey, 430 U.S. 144 (1977), this

Court upheld a voluntary, race-conscious districting plan

for state legislative seats in Kings County, New York

(Brooklyn). Justice White, joined in that part of his

opinion by Justices Stevens and Rehnquist, noted that

there was "no doubt that in preparing the [districting

plan], the State deliberately used race in a purposeful

manner," id. at 165: the State had intentionally drawn

several districts with effective black voting majorities of

between 65 and 90 percent, see id. at 151-52.

Nevertheless, because the plan could be viewed as seeking

"to achieve a fair allocation of political power between

15

white and nonwhite voters in Kings County," id. at 167, it

was permissible.4 Of particular salience to this case, UJO

did not uphold the New York plan because the plan was

necessarily required by the Voting Rights Act; rather, it

upheld the plan because it represented one of potentially

many acceptable responses to the political realities of

Kings County.5

Moreover, to say that a State cannot pay attention to

race in drawing districts ignores reality. By its very

nature, the essence of the districting process is the

aggregation of people by virtue of their group

characteristics, whether these be geographical, political,

social, or racial. Cf Reynolds v. Sims, 377 U.S. at 623-24

(Harlan, J., dissenting). The reality of American life is

4 Although UJO v. Carey produced several opinions, only then-

Chief Justice Burger explicitly disagreed with Justice White’s analysis,

and Justice Stewart, joined by Justice Powell, reached a conclusion on

this issue essentially identical to Justice White’s. See 430 U.S. at 179-

80.

5 Similarly, in Gaffney v. Cummings, this Court upheld a

"bipartisan gerrymander" of the Connecticut State Assembly because

the resulting plan "purports fairly to allocate political power to the

parties in accordance with their voting strength and, within quite

tolerable limits, succeeds in doing so." 412 U.S. at 754. The Court

noted that:

The Board also consciously and overtly adopted and

followed a policy of "political fairness," . . . . Senate and

House districts were structured so that the composition of

both Houses would reflect "as closely as possible . . . the

actual [statewide] plurality of vote on the House or Senate

line in a given election."

Id. at 738.

The Court’s discussion frequently relied on racial vote dilution

cases in reaching its conclusion, see id. at 753, 754, thus suggesting

that a similar analysis would apply in the context of claims of race

conscious but fair districting.

16

that black communities are often geographically compact

and that black voters often share a variety of

socioeconomic characteristics that affect their voting

behavior. Since the demographic profiles of a State "are

available precinct by precinct, ward by ward," Gaffney v.

Cummings, 412 U.S. at 735, it would be essentially

impossible for a districting body not to foresee the likely

racial impact of possible apportionment schemes.

Second, since the Apportionment Board was not

required to justify its decision to draw majority-black

districts by first establishing that alternative approaches

would violate section 2, it had no obligation to conduct

any formal inquiry before proposing its plan. The district

court’s holding to the contrary reflects a complete

misunderstanding of the basis of the Apportionment

Board’s authority.

To ensure that judicial invalidation of a

democratically adopted plan is warranted, Congress and

this Court have required district courts to engage in an

intensely local appraisal of the design and impact of a

challenged plan, and to make detailed findings of fact.

Thornburg v. Gingles and the Senate Report accompanying

the 1982 amendments to the Voting Rights Act create a

detailed analytic structure for this necessaiy judicial

factfinding. See Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. at 46-51;

S. Rep. No. 97-417, pp. 28-29 (1982) ["Senate Report"].

The district court must "consider the totality of the

circumstances and ... determine, based upon a searching

practical evaluation of the past and present reality ....

[and] an intensely local appraisal of the design and impact

of the contested electoral mechanisms" whether black

voters have an equal opportunity to participate and elect

their preferred candidates, Gingles, 478 U.S. at 79

(internal quotation marks and citations omitted).

17

The totality-of-the-circumstances inquiry mandated by

the Senate Report and Gingles is a prerequisite to finding

section 2 liability. But neither Congress nor this Court

has ever required states to undertake a similarly

painstaking analysis before they enact a plan in the first

instance. Such a requirement would run roughshod over

longstanding principles of federalism and deference to the

political branches in this most quintessential^ political of

endeavors. Of course, states are free to consider various

Gingles or Senate Report factors in developing their plans,

and prudent plan drawers might seek to avoid the later

invalidation of their plans by thinking about whether the

plans comply with section 2. And legislatures should

review alternative plans to ensure that the plan they

ultimately select does not dilute minority voting strength.

But as long as the plan a State ultimately adopts does not

violation section 2, the analysis a State used to arrive at

that plan is not subject to being questioned separately.

In short, the district court’s January 31 opinion

provided absolutely no basis for invalidating Ohio’s Plan.

B. The District Court Itself Failed to Comply With

Section 2 ’s Requirements

Because it was preoccupied with its idiosyncratic

theory imposing upon the Apportionment Board the

obligation to follow Gingles’ analytic framework, the court

below completely neglected to follow section 2 itself. The

district court failed to find a single fact that would justify

a conclusion that Ohio’s Plan violated the Voting Rights

Act.

To begin with, the district court completely flouted

Gingles’ directive to conduct an "intensely local appraisal

18

of the design and impact of the contested electoral

mechanisms." 478 U.S. at 79 (quoting Rogers v. Lodge,

458 U.S. 613, 622 (1982)). In Gingles itself, after all, this

Court upheld North Carolina’s use of a multimember

district in the Durham area despite finding such districts

invalid in other parts of the State. See id. at 77. And it

specifically disapproved of lumping different challenged

districts together: "The inquiry into the existence of vote

dilution ... is district-specific. When considering several

separate vote dilution claims in a single case, courts must

not rely on data aggregated from all the challenged

districts ...." Id. at 59 n. 28. In this case, however, one

can search the district court’s opinions in vain for any

description of the characteristics of the various challenged

districts that result in the denial of an equal opportunity

for black voters to elect their preferred candidates.

Indeed, the majority opinion does not even identify the

challenged districts by number. The closest it comes to

discussing any relevant information about the challenged

districts is to mention the "average plurality" received by

black candidates in various unidentified districts in various

unspecified elections sometime between 1984 and 1990,

App. to Juris. St. 7a, and to refer to the level of crossover

voting in some districts, id. at 133a. But the court made

no factual findings at all with regard to the socioeconomic

disparities, past election results, campaign issues or any

other Senate Report factor.

As a consequence, the district court never identified

how black voters were actually injured by the challenged

plan. It referred to plaintiffs’ contention that the Plan

involved both improper "packing" and "cracking," App. to

Juris. St. 7a, but it never identified where either of these

injuries occurred.

19

This cavalier treatment not only defied the clear

requirements of Gingles; it also flouted the requirement

of Fed. R. Civ. P. 52(a) that the court make findings of

fact sufficient to permit intelligent appellate review. Even

the most cursory comparison of the opinions in this case

with the detailed treatment of racial vote dilution claims

by two district courts whose conclusions were affirmed by

this court — see Thornburg v. Gingles, see Gingles v.

Edmisten, 590 F.Supp. 345 (E.D.N.C. 1984), aff’d 478 U.S.

30 (1986); Jeffers v. Clinton, 730 F. Supp. 196, 204-05

(E.D. Ark. 1989) (three-judge court), summarily aff’d, 111

S. Ct. 662 (1991) — shows how far short of the mark the

opinions in this case fell. And for a court to devote one

sentence, with no factual support, to a holding that the

State of Ohio was deliberately racist in adopting the Plan

- the clear import of its finding that there was a Fifteenth

Amendment violation, see App. to Juris. St. 119a — is

judicially irresponsible. Moreover, it is not defensible

under this Court’s precedent. See, e.g, City of Mobile v.

Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980).

Moreover, had the district court paid any serious

attention to the issue, it would soon have seen that

plaintiffs’ theory of their case contained within itself its

own rebuttal. Plaintiffs began by claiming that under the

1981 apportionment scheme, some black voters in

particular majority white districts were nonetheless able to

elect the candidates of their choice. See App. to Juris. St.

7a, 13a, 132a-33a.6 If that is true (and amici take no

6 We also note, by the way, the essential triviality of evidence of

responsiveness such as the voting records of white legislators who are

not dependent on the support of the black community for their

continued tenure. Although the district court pointed to such

evidence, see App. to Juris. St. 7a, it failed to heed the Senate

Report’s directive that "proof of some responsiveness" is not

20

position on that question), then, at least as to those

districts, there was no legally significant racial bloc voting.

See Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. at 54-61 (discussing the

concept). But if there was no legally significant racial

bloc voting under the 1981 plan, then unless plaintiffs can

show that the 1991-92 Plan somehow generates legally

significant racial polarization — and there is nothing in the

record to support this claim — they cannot demonstrate

one of the two "most important Senate Report factors,"

namely, racial bloc voting. Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S.

at 48 n. 15.

Because the district court failed to find any of the

facts that tend to show that under a challenged plan,

blacks have less opportunity than other citizens to

participate in the political process and elect the

representatives of their choice, it had absolutely no basis

for striking down the Plan as violative of the Voting

Rights Act. The complete failure to conduct the required

"intensely local appraisal" makes this case an

inappropriate vehicle for considering fine points about

how courts should assess section 2 challenges. Thus,

contrary to the Solicitor General’s invitation, see Brief for

the United States as Amicus Curiae Supporting

Appellants at 10, 15-16, this Court should not address the

broader questions of whether and how each of the Gingles

preconditions should apply to state reapportionment

particularly probative. See Senate Report at 29 n. 116. In part

because the finding of responsiveness is so subjective and so

dependent on which aspects of legislative performance are deemed

relevant, courts have generally avoided the inquiry. See, e.g., Gingles

v. Edmisten, 590 F. Supp. 345 (E.D.N.C. 1984) (three-judge court),

ajfd, 478 U.S. 30 (1986).

21

plans.7

C. The District Court’s Holding on Plaintiffs’ Fifteenth

Amendment Claim was Unsupportable

The district court’s treatment of the Fifteenth

Amendment issue is unfortunately typical of its overall

approach to this case. Almost as an aside in its March 10

Order, the district court included one sentence: "As noted

in the Conclusion of our January 31, 1992 order and

opinion, it has heretofore been unnecessary in these

proceedings to reach the constitutional issue presented,

but we now proceed to decide that the plan as submitted

is also violative of the Fifteenth Amendment of the

United States Constitution." App. to Juris. St. 119a. That

sentence -- and a brief assertion that the Board must have

intended to dilute black voting since that is the likely

effect of the Plan, id. at 141-42a - is the sum total of the

lower court’s analysis of plaintiffs’ claim that the State of

Ohio deliberately set out to deny its black citizens their

fundamental constitutional right to vote.

It is hardly surprising that the district court cited no

case law from this Court in support of its holding, for to

cite the only case in which this Court has struck down a

State’s delineation of district boundaries on Fifteenth

Amendment grounds would have showed the complete

absurdity of the district court’s holding. There is nothing

in this record to suggest that Ohio’s decision to draw

several majority-black legislative districts even remotely

7 If the Court ultimately remands this case for further proceedings

in the district court, those issues can be addressed in the first instance

in the context of the kind of detailed factfinding required in section

2 cases.

22

resembles Alabama’s complete exclusion of black voters

from Tuskegee, see Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339

(1960).

Amici emphasize that we take no position on the sort

of proof of discriminatory intent which might establish a

Fourteenth Amendment violation: that issue was neither

raised, briefed, nor decided below and this Court

therefore should not reach it. But cf. Rogers v. Lodge, 458

U.S. 613, 622 (1982) (setting out the standard for

assessing Fourteenth Amendment-based claims of racial

vote dilution). We argue here only that no Fifteenth

Amendment violation has been shown. The court below

erred in transforming its disagreement with the political

philosophy of the Ohio Apportionment Board into a

constitutional condemnation of the Board as intentionally

discriminatory.

23

Conclusion

This Court should affirm the judgment below solely

on the ground that the Board failed to provide sufficient

justification for the maximum population deviation among

districts.

Respectfully submitted,

Antonia Hernandez

Theresa Busullos

Mexican American Legal Defense

634 South Spring Street, 11th Floor

Los Angeles, CA 90014

(213) 629-2512

Barbara R. Arnwine

Brenda Wright

Lawyers’ Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 371-1212

Kenneth Kimmerling

Arthur Baer

Puerto Rican Legal Defense and

Education Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-3360

Pamela S. Karlan

Yale Law School

P.O. Box 401A Yale Station

New Haven, CT 06520

(203) 432-1620

C. Lani Guinier

University of Pennsylvania

Law School

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, PA 19104-6204

(214) 898-7032

Julius L. Chambers

* Charles Stephen Ralston

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Angelo N. Ancheta

Asian Pacific American Legal

Center of Southern California

1010 So. Flower St., Suite 302

Los Angeles, CA 90015

(213) 748-2022

Counsel o f Record

Counsel for Am ici Curiae