Attorney Notes; Memorandum Brief of Respondents in Reply to Petitioner's Brief in Support of Motion for Summary Judgment; Bozeman v. State Court Opinion; Reply of Respondents to Petitioner's Response to This Court's Order of December 2, 1983; Petitioner's Memorandum of Law in Support of Motion for Summary Judgment

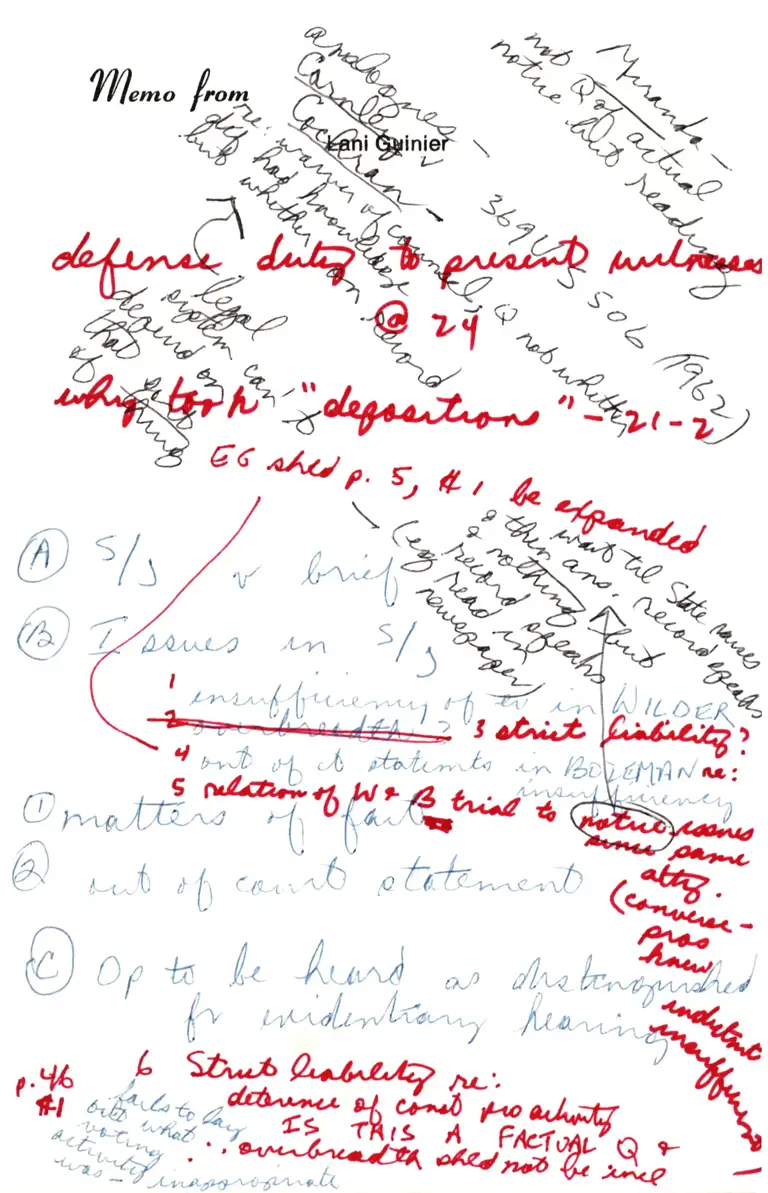

Working File

February 24, 1984

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Attorney Notes; Memorandum Brief of Respondents in Reply to Petitioner's Brief in Support of Motion for Summary Judgment; Bozeman v. State Court Opinion; Reply of Respondents to Petitioner's Response to This Court's Order of December 2, 1983; Petitioner's Memorandum of Law in Support of Motion for Summary Judgment, 1984. a36d1e84-ed92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/55fbbd6c-1c5b-4161-8931-a92f460126ef/attorney-notes-memorandum-brief-of-respondents-in-reply-to-petitioners-brief-in-support-of-motion-for-summary-judgment-bozeman-v-state-court-opinion-reply-of-respondents-to-petitioners-response-to-this-courts-order-of-december-2-1983-petiti. Accessed February 04, 2026.

Copied!

*. -7,

\ -a*,

-1-)r

,a,t +t l, A, ,,,r) 6-)'

{'

n , r^ , oL, *,Lio,., , ,

[h-re^

Wl*e

LIu.N nta^^/)

-/L-,*/*r*

Dayna L. Cunningham

CIVIL ACTION

N0. 8r-H-579-H

vs.

EALON l,l. LAMBERI, et &1 . ,

Respondents

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR TEE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF AIABAMA

NORTHERN DIVISION

MAGGIE BOZEMAN,

Peti t i oner

I-IEITIORANDUI-I BRIEF 0F RESP0NDENIS IN REPIY T0

Petitioner argues her eonvlction should be set asitle

because she uas convicted untler a clefeetive indictment.

Petitioner basically claims the indictment was

rend.erecl defective by the trial court's iury

instructions, i.e., the trial eourt conmitted error in

instructing the jury as it dld. Petitioner also contenlls

the jury instructions erroneously subjeeted petitioner to

"striet 1iabi1ity."

At the end of the trlal court's charge to the iury,

tlefense counsel made no objeetion to the courtrs

instructions. (n. 208)

A proper obJection to the charge would have been to

object on the grountls that lt was error for the trial

court to instruct the Jury as lt did and to cite the

grouncls therefor which petitioner now raises ln her

habeas petition.

Under Alabama procetlural Ian, petitioner eould have

obJectetl at the end of the courtrs charge and clted as

grouncls the matters raised here.

This woultl have given the trial eourt an opportunity

to take corrective action 1f intleed the grounds were

meritorlous. And, assuning an atlverse ruling, Petitioner

woulcl have been able to present these clalms to the

Alabana appellate courts.

However, einee petitioner made no obJectlon to the

trial eourt's jury charge, the grounds raised here rf,ere

naived for purposes of tlirect appeal ln state court.

By not objecting, petitioner has by-passecl the state '- 4z\b.,

forum in which these grounds eoultl have ancl should have \/

been lltigated. Moreover, petitioner woultl have been in

a position to assert these grounds in a petition for writ

of certiorari to the U.S. Suprene Court. Knewel v. Ege.,

258 u.s. 442 (1925).

4

Alabama law ls very clear that ln ortler to preserve

for review allegecl errors in a trial court's oral charge,

a ilefentlant must object, point out to the trial court the

a1Ieged1y erroneous portions of the charge, ancl assign

specific grounds as to uhy the tlefentlant believes there

was error. Brazell v. State, 425 So.2tl 32, (Afa. Crim.

App. 1 982 ).

Failure to make suffieient objection to preserve an

jury instruction waives the allegecla11eged.1y erroneous

error for purposes

4o9 So.2d 94, (Ala.

lrloreover, the

the Jury retires.

of appellate revieu. Hill v. State,

Crim. App. 1981 ).

objectlon 1s walvecl unless

Showers v. State, 4O7 So.2d

macle before

1 59, 172

(na. 1981 ).

Since petitioner made no objection to the trial

courtrs oral charge, petitioner failed to comply vith.

Alabama procetlural 1aw on this point. Therefore, the

petition is tlue to be ttenietl on all assertions concerning

the trial court's oral charge unless petitioner can show

cause for failure to objeet and actual preiudiee

resulting from the eharge. !g!1@, 411 U.S.

72 (tgtt).

Petitioner then le left here vtth her challenge to

the sufficiency of the intlctment made in her pretrial

motion which challengetl the indictment as being vague and

overbroad. (n. 218-220)

It was only upon the language of the lndictment that

the Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals rulecl on its

sufficiency and helcl the inclietment was suffieient-

Suffieiency of a state lndictment is not a natter

for fecleral habeas corpus relief unless it can be shown

that the tndictment ls so tlefective that the convietlng

court hacl no Juriscliction. Branch v. Este11e, 611 F.2d

1229 (>tn Cir. 1980). 0r, stated another YaY, petitloner

must show that untler no circumstances could a valitl

eonviction result fron facts provable under the

indictment. {gt4q_o_g v. Estellg , 7O4 F.2d 232 (lti, Cir.

1983); Cramer v. Fahner, 683 I'.2d 1175 (Ztrr cir. 1982);

Knewel v. Egan,258 U.S. 442 (1925).

Thus, since petitioner has not shovn cause for

failure to objeet to the trial courtts instructions, and

since the inclictnent was clearly sufficient to confer

jurisdiction on the state trial court to try petitioner

for vtolatlng Alabana Code 1975, $ I7-2r-1, the notlon

for sunmary Judgment

petttlon ts due to be

to be tienl.e<l, and the

on these tsgueS.

Reepeetfully subnttted,

ls due

dented

vl.hllllv na vltnvv

ATTORNET GENERAI,

SSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAI

ASSISTATI ATTORTXf, GENERAT

cEuIFrqtTE_q SERVICE

r hereby certify that on thie z4th day of Febru&rY,

1984, I did Eerve a copy of the foregolng on the attorney

for Petitioner, Vanzetta Penn Durant, 5r9 Martha Street'

llontgon€ry, Alabaroa ,5108, by hand delivery.

RIVARD }IELSON

ASSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAI

SSISTANT ATTORNEY GENERAI,

ilnriltr

--/hod

O.l

t.

-

3Iitcltt

rxEt

ii-

[U.b h.Orl

-

;.r rrri-

dirtrict

dd.nt

rtil my

,a{

movrl

,hrr.

,

osnry

r dry.

.r.hy

*

u.liri-

ntfu

ort,

.Or

BOZEMAN v. STATE

Cltora 1661.A*,,l{,r So.2d t67

APPENDIX-Continued

APPLICATION FOR AESENTEE DALI.OT

lrr/

Ara. 167

l-14111

To

Dcrr Sir:

t sill bc uorblc to rotc rt my rctuhr polliag plrcc bccrw of my rbccncc from thc co *rr, o*-Q;!Af

@ lll", *, i'iifl^flTi

"r::ffi"'I;

IH :'[fil" u *"

t rlro mrtc rp,plicerion f1tb.cDtcc \.Uor for Prinrry Rmott Elccrion if nccanery. ya ! Xo E

Aoolicent'rN.,[flc \O U h I (l \ D O ;

^

;z

Prccinct iD ?hich I lrrt rcrrd A ,

Mril b.llot to .d&c.l-

If ,ipcd by mrrl the^aenc of thc rita€ nu.r bc dgDcd hcrco!.

iltua igdrtut. Y^9 '"- .U}t<4ltz

Thir rpplicuio drry bc heodod by lhc ryplk st to lbc rstirt , or fotildcd ro hih by Uait d Surr. Mdl.

-rw\-(o E xrYllfs-fiIysr-D\.ir

Ex parte Julia P. WLDER.

(re: Julia R. Wilder

v.

State of Alabama).

8H:t7.

Supreme Court of Alabama.

July 24, 1981.

Certiorari to the Court of Criminal Ap

peals,401 So.2d 151.

BEATTY, Justice.

WRIT DENIED_NO OPINION.

TORBERT, C. J., and MADDOX, JONES

and SHORES, JJ., concur.

Massie S. BOZEMAN,

v.

STATE.

2 Div. tl6.

Court of Criminal Appeals of Alabama.

March 31, lg8l.

Rehearing Denied April 21, 1981.

Defendant was convicted in the Cirrcuit

Court, Pickens County, Clatus Junkin, J., of

voting violations, and she appealed. The

C,ourt of Criminal Appeals, DeCarlo, J., held

that the evidence was sufficient to support

the conviction.

Affirmed.

Writ denied, Ala.,40l So.Zt l?1.

l. Criminal Law e552131

In reviewing sufficiency of circumstan-

tial evidence, test to be applied is whether

jury might reasonably find that evidence

excluded every neasonable hypothesis ex-

cept that of guilt, not whether such evi-

dence excludes every rcasonable hypothesis

but gnilt, but whether jury might neason-

ably so conclude.

168 Ala.

2. Criminal Law ell44.l3(2)

On rcview, Court of Criminal Appeals

is required to consider evidence in light

most favorable to prosecution.

3. Criminal Lsw c=1144.13(4, 5)

Court of Criminal Appeals must take

evidence favorable to prosecution as true,

and accord to state all legitimate inferences

therefrom.

4. Criminal Law ea552(4)

Circumstantial evidence must be ac-

corded same weight as direct evidence when

it points to accused as guilty party.

5. Criminal l,aw e?42(l)

Truthfulness of tescimony is for triers

of fact.

6. Elections F329

In prosecution for voting violations, ev-

idence was sufficient to support conviction.

7. Jury e33(5)

In prosecution for voting violations, de-

fendant's constitutional rights were not vio-

lated when State used its peremptory

strikes to exclude all blacks from jury ve-

nirr.

Solomon S. Seay, Jr. of Gray, Seay &

Langford, Montgomery, for appellant.

Charles A. Graddick, Atty. Gen., and

Thomas R. Jones, Jr., Asst. Atty. Gen., for

appellee.

DeCARLO, Judge.

The grand jury of Pickens County indict-

ed the appellant and charged her in a three-

count indictment with voting more than

once or dep,ositing morc than one absentee

ballot for the same office as her vote, or

casting illegal or fraudulent absentee bal-

lots. This is a companion case to tiltfier v.

Stare,401 So.zd 151(198f). 'r

The indictment in this case, omitting the

formal parts, reads as follows:

"The Grand Jury of said County charge

that, before the finding of this indict-

ment, Maggie S. Bozeman, whos€ name

to the Grand Jury is otherwise unknown:

4OT SOUTHERN REPORTER. 2d SERIES

..COUNT ONE

"did vote morne than once, or did deposit

more than one ballot for the same office

as her vote, or did vote illegally or fraud-

ulently, in the Democratic Primary Run-

off Election of September 26, l9?8,

..COUNT TWO

"did vote more than onoe as an absentee

voter, or did deposit more than one abeen-

tee ballot for the same office or offices as

her vote, or did cast illegal or fraudulent

absentee ballots, in the Democratic Pri-

mary Run+ff Election of September 26,

1978,

..COUNT THREE

"did cast illegal or fraudulent absentee

ballots in the Democratic Primary Run-

off Election of September 26, 1978, in

that she did deposit with the Pickens

County Cirrcuit Clerk, absentee ballots

which were fraudulent and which she

knew to be fraudulent, against the peace

and dignity of the State of Alabama."

After a two-day trial which ended on

November 2, 1979, the appellant was found

guilty as charged in the indictment and

sentenced to four years imprisonment. She

gave notice of appeal and filed a motion for

a new trial. The motion was subsequently

denied when no testimony or argument was

made on behalf of the motion.

The evidence presented at trial was sub.

stantially as follows:

Ms. Janice Tilley's testimony conceraing

absentee voting procedurcs was substantial-

ly similar to her testimony in Wr?der, supra

Ms. Tilley stated that the week preceding

the September 26, 1978 Democratic Primary

Run-off Election she gave the appellant

approximately twenty-five to thirty absen-

tee voting applications. M* Tilley t€stified

that the appellant came to the Pickens

County Circuit Clerk's office requesting the

applications on several occasions. Ms. Til-

ley specifically remembered seeing the ap

pellant on September 25th in the company

of Julia Wilder. Ms

the appellant in a

office at that time, '

ber whether appella

ballots to the office.

a number of ballol

same address, 601

west, Aliceville, Ala

During cKxis-exar

tified th8t ther.e i

applications for ah

up by the voters th

Pickens County !

testimony was subs'

testimony in Wildet

Mr. Charles Tatr

cerning his partici

the voting irregula

1978 election. In

which had been dor

box, Investigator T

nine of the bellots

Paul C. Rollins. I

tion, Mr. Tate exan

Circuit Clerk's rc<

corresponding 8pp

for the abaentee h

be the case.

During crosst-€xa

fied that the thir'l

by Mr. Rollins, hac

for the same penrc

Mr. Paul L. Roll

Tuscaloooa, tcstifir

appellant nine or

was shown several

he notarized on S

office in Tuscaloo

had not tleen sign,

was not pensonall

penons who had s

that appellent, Ju

ladiee brought thr

werc present whe

further t€stified

the appellant abo

On qres-exami

that he advis€d I

end the other tn

signing the ballot

BOZEMAN v. STATE

CltG a$ AI&Cr.ADP.,'Ol SG2d 167

Ala. 169

sit

ce

d-

of Julia Wilder. Ms. Tilley recalled seeing his presence' Mr' Rollins testified that pri-

the appellant in a ear outside the clerk's or to notarizing the ballots he received two

office at that time, but she did not remem- telephone calls pertaining to the ballots and

ber whether appellant herself returned any that one of the calls was finm the appel-

ballots to the office. Ms. Tilley noticed that lant. Mr. Rollins stated that he was paid

a numhr of ballots were mailed to the for his services and that he subsequently

same address, 601 Tenth Avenue North- went to Pickens County to find those per-

west, Aliceville, Alabama. sons who had allegedly signed the ballots'

During cross-examination, Ms' Tilley tes- He had the appellant's a'ssistance on that

tified that there is no requirement that occasion' however' he was sure he did not

applications for absentee voting be picked go to Pickens County prior to September 26'

,p Uy tfr" voter"s thems€lves. 1978'

Pickens County Sheriff Louie Coleman's Mrs' Maudine ['atham testified that she

testimony was substantially the same as his was a registered voter of Pickens County

testimony in lVilder, supra. and stated that she signed an application to

Mr. charres rate testiried basicauv con- ;:ff:tr1?""*#i"T:[ffi,tn: H:

cerning his participation in investigating testified that she never received a ballot to

the voting irregularities in the September, vote.

19?8 election. In counting the ballots

which had been double locked in the ballot Mrs' Annie B' Phillips' Mrs' Mattie o'

box, Investigator Tate observed that thirty- Gipson and Mr' Nat Dancy's testimony was

nine of the ballots had been notarized by substantially the same as their testimony in

Paul C. Rollins. As part of his investiga' ffilder' supra'

tion, Mr. Tate examined the Pickens County Mrs. Janie Richey testified that Julia Wil-

Circuit Clerk's records to verify whether der helped her to vote absentee in the Dem-

corresponding applications had Len filed ocratic Primary Run'off Election' She had

for the absentee ballots, which he found to no objection to the way Ms. Wilder marked

be the case. her ballot'

During cross-examination, Mr. Tate testi- Mrs. Fronnie B. Rice testified that she

fied thal the thirty-nine ballots, notarized voted absentee in the Democratic Primary

by Mr. Rollins, had all been marked to vote Run-off Election, and that her application

and ballot came in the mail. She statedfor the same penpn.

Mr. Paul L. Rollins, a notary publie from that she marked her ..X's', without assist.

Tuscaloosa, testified that he had known the ance and then signed her name on the bal-

appellant nine or ten years. Mr. Rollins lot' Mrs' Rice gave her ballot to Julia

was shown several of the thirty-nine ballots Wilder' She did not know Paul C' Rollins'

he notarized on Septembe. 23, t9?8 in hit Ninety-three-year-old Lou Sommerville

office in Tuscaloosa. All of these ballots testified that she was a registered votcr in

had not been signed in his presence and he Pickens County and that Julia \ililder as-

was not p""*n"tty acquaintcd with those sisted her in voting in the September 26,

Petlons who had signed. Mr. Rollins stated 19?8 Democratic Primary Run-off Election'

that appellant, JulL Wilder and two other Mrs. Sommerville stated that she placed her

tadies Lrought the balloti to his office and ballot in the box at the polls. Mrc' Som-

wene present when he no'tarized th"m. He merville insistcd that Julia wilder and her

further t€stified that he had talked with daughter wer.e the only persons who had

the appellant about notarizing the ballots. ever assisted her in voting absentee, and

On crcss+xamination, Mr. Rollins stat€d she made her own "X" mark' Mrs' Som-

that he advised the appellant, Ms. Wilde" merville did not know Paul C' Rollins'

and the other two ladies that the pemons Sophia Spann, whose absentee ballot was

rigning the ballots werc supposed to be in notarized by Paul Rollins at the appellant's

ee

n-

as

nt

ri-

t6,

3e

n-

in

1S

ts

le

:e

In

rd

rd

te

,r

v

13

s

l-

L

c

v

,t

d

s

e

Y

170 Ala. 40r SOUTHERN REFORTE& 2d SERTES

request, testified that she always voted in

Cochran, Alabama, and that she had never

voted in Aliceville. Ms. Spann stated that

she had never voted an absentee ballot, but

that the appellant had come to her house

and had talked to her about it. She had

known the appellant all her life. On the

occasion the appellant talked with Ms.

Spann, Ms. Spann testified that the follow-

ing conversation occurred:

"She just asked me because my husband

was sick. And she asked me did I want

her to vote for me. And I wouldn't have

had to come over to Aliceville.

"I said, 'maybe. I don't have to go to

Aliceville. I votes in Cochran.' I haven't

voted in Aliceville in my life. I votes

here. Just started to voting right in

Cochran. That's all I vote." [Em-

phasis added.l

Ms. Spann denied ever making applica-

tion for an absentee ballot, or to having

ever signed her name to one. See lVr7der,

supra, and the attached appendix.

On cross-examination, Ms. Spann testi-

fied that she knew Julia Wilder, but .,I

don't know her nothing like I do Maggie."

She denied that Julia Wilder had ever been

to her house and further denied ever having

discussed voting with her on any occasion

and said, "I don't know anything about

that."

Ms. Spann testified that the appellant

talked to her before voting time. "She

thought I had tp come to Aliceville and she

was helping me. And I told her I didn't

have to go to Aliceville, I votes in Cochran,

and I didn't need the help." Ms. Spann

next testified that when she went to Coch-

ran to vote, a voting official told her she

had already voted in Aliceville; "somebody

had voted for me over at the Alice-

ville...." I

From the record:

"Q. A question like that came up?

"4. Yes, sir. When I walked in, Mrs.

Charlene said, there's my mama. How

come you so late? . . . . So, she said,

'well, that's all right. Somebody done

votd for you over at the Aliceville,' and

she showed it to me. And she asked me

did I know that writing. I didn't know

that writing.

'Q. Now, who told you that?

"A. The lady down at Cochran, the lady,

Mrs. Charlene, Mr. Hardy Baldwin's wife.

'Q. Did she tell you how she come to

know that you had voted?

"A. It was in the box at Cochran. The

paper was in the box and he [sic] got it

and showed it to me and asked me did I

know that handwriting. I didn't know it.

That's all of it." [Emphasis added.]

Mrs. Lucille Harris' testimony was sub-

stantially the same as her testimony in WrI-

der, supra.

At the conclusion of Mrs. Harris'testimo-

ny the State rested its case and appellant's

motions to exclude were denied. The de-

fense did not present a case. Closing argu-

ments rvere had and the trial court prcperly

charged the jury as to the law, there being

no exceptions taken.

I.

Section 17-?3,-1, Code of Alabama 1975,

is constitutional. Wilder, supra.

II.

The indictment in this case, which is iden-

tical in pertinent part to the indictment in

Wilder, supra is constitutionally valid. Wil-

der, supra.

I II.

[-51 The evidence, although circum-

stantial to a large degree and confusing in

several instances, was sufficient to support

the jury's verdict. In reviewing the suffi-

ciency of circumstantial evidence the test to

be applied is "'whether the jury might rea-

sonably find that the evidence excluded ev-

ery reasonable hyp,othesis except that of

guilt; not whether such evidence excludes

every reasonable hypothesis but guilt, but

whether a jury might reasonably so con-

clude. (Citations omitted).'" Dolvin v.

Stare, 391 So.2d l3:|, l3? (A1a.1980); Cumbo

v. State, 368 So.zd 871, 874 (Ala.Cr.App.

19?8), cert. denied,368 So.2d 8?7 (Ala.19?9).

On review, this cour

the evidence in the

the prosecution. )

*.%l 1242 (Ala.Cr..

Stsre, 37 Ala.App. 4

This court must takr

to the prosecution at

State all legitimate

Johnson v. Statr-, 1

App.), cert. denied,

1979). Circumstanti

corded the same wr

when it points to tt

p8rty. Inke v. St

Cr.App.19?6). The

timony was for the

SA8ae, 335 So.tul2U

t6l Thereforc, r

cording the verdict

tion of @rnectnesa,

sufficient to suppor

convinced that the r

unjust and was n(

weight of the evidr

2&l Ala. 4L2, DS *

t?l There is no r

argument that he

were violated when

emptory strikes to

the jury venine. T

tively answered in

u.s. 202, 85 S.Ct

(1965); Thigpn v.

?r0 So.2d 666; C

So.zd 89 (Ala.Cr.Ap

We have searchr

prejudicial to app

none, thercforc, the

by the Pickens Cir

AFFIRMED.

All the Judger o

@

HANDLEY v. CITY OF MONTGOMERY

clt' a* Alr'cr'ADD' 'ol tlc2d l7l

Ala. l7l

n

t-

1-

in

rt

:i-

La

a-

v-

of

es

ut

rn-

v.

b

,p.

e).

On review, this court is required to consider

the evidence in the light most favorable to

the prcsecution. McCord v' Statc, 379

b.%J l2{:2 (Ala.Cr.App.l979); Coleman v'

Stite, g7 Ala.App. 406, 69 So'2d 481 (1954)'

This court must take the evidence favorable

to the prosecution as true, and accord to the

State all legitimate inferences therefrom'

Johnson v. Statc, 3?8 So.2d 1164 (Ala'Cr'

App.), cert. denied, 3?8 So.2d 1173 (Ala'

19?9). Circumstantial evidence must be ac-

corded the same weight as direct evidence

when it points to the accused as the guilty

party. Incke v. StaAe, 338 So'2d 488 (Ala'

Cr.App.19?6). The truthfulness of the tes'

timony was for the triers of fact' May v'

Stace, 335 *.tul ?A2 (Ala.Cr.App'1976)'

t61 Therefore, we conclude, after ac-

cording the verdict all reasonable presumP

tion of @rrectness, that the evidence was

sufficient to support the verdict' We are

convinced that the verdict was not wrong or

unjust and was not patently against the

weight of the evidence' Bridges v' Statn,

28{ Ala. 412, nS So.zd 821 (1969)'

IV'

t?l There is no merit to appellant's final

argument that her constitutional rights

were violated when the State used its per'

emptory strikes to exclude all blacks from

the jury venire. This question was defini-

tively answered in Swain v, Alabama,}80

U.S. m2, 85 s.Ct. 8?/1, lg L.Fd.zl 759

(1965); Thigpen v. Stttn,49 Ala'App' 233'

ffO So.2l 666; CarPntnr v. State, 4Ul

So.2d 89 (Ala.Cr.APP.r980).

We have searched the record for error

prejudicial to appellant and have found

none, therefor.e, the judgment of conviction

by the Pickens Circuit Court is affirmed'

AFFIRMED

All the Judges @ncur.

Ex parte Maggie BOZEMAN'

(re Meggie S. Bozcman

v.

State of Alabeme)'

8G53&

Supreme Court of Alabama'

JulY 24, 1981'

Certiorari to the Court of Criminal Ap

peals,40l So.2d 16?.

BEATTY, Justice.

WRIT DENIED_NO OPINION.

TORBERT, C. J., and MADDOX, JONES

and SHORES, JJ., concur'

Roger HANDLEY et aL

v.

CITY OF MONTGOMERY.

3 Dtv. 195.

Court of Criminal Appeals of Alabama'

March 31, 1981'

Rehearing Denied MaY 5, 1981'

Defendants werc convictcd before the

Circuit Court, Montgomery Crcunty, Joseph

D. Phelps, J., of unlawful assembly and

paradin! without permit, and they apryal

ed. Th; Court of Criminal Appeals, DeCar'

lo, J., held that: (1) article of city traffic

code requiring permit for parades

"19-

p*

cesEionE was valid on ita face and did not

constitute an impermiasible prior regtraint

of Fint Amendment freedoms; (2) article

was not unconstitutionally applied against

Ku Klux Klansmen arreotpd lor demon-

I.':AGGIE BOZElIAN,

Petitioner

vGlU.

EAION I,I.

CIVII ACTION

N0. er-n-574-H

'l*, /'\4/ ? {r^'

rt.''*'/ tL,''\<-

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE ITIIDDI,E DISTRICT OF AI,ABAI'1A

NORTHERN DIVISION

IAUBERT, €t aI.

Bespondents

REPTY OF RESPONDENTS TO PETITIONER'S RESPONSE

0n Decembet 2, 198r, this Court entered an order

requiring petiti.oner to file "a brief or other document

setting out her positions on the issues in this case."

Petitioner has filed vhat she ca1ls a "response" to

the Courtrs order in whieh she merely lists what she

believes to be the elght issues raised by the petition

and in uhich she states she intends to file a notion for

sunnary judgnent as to her listed issues B, C, and D.

fn replying to this 'response' by petitioner, the

respondents are unsure as to how to proceed since

petitioner makes no argunent as to her position based on

r\\'\t\

the state trlal reeortl. Iloyever, respondente ui11

attempt to address eaeh of the issues Ileted tn the

tresponBe. n

In fssue A, as denominated 1n petitionerre

"reeponse," questions the suffieieney of the eviclence to

support petitionerrs convietion uncler ALabaua Code 1975,

$ r ?-zr-r .

Petitioner contends the only eviclenee Linking, her to

the absentee ballots in question nas that she nay have

been present when the absentee ballots were fraudulently

notarized, but that there yas no eviclence that petitioner

or anyone assoeiated with her had cast any of the 19

ballots or that any of the ballots Yere east

fraudulently.

...

It is clear from the record of petitionerrs trial

that she participated in a scheme to east two or Eore

fraudulent ballots for a single candidate in the 197e

Democratic Primary run-off election.

Petitioner yas present with Julia Hilder when the

notary public notarized several absentee ballots and when

none of the persons vho had purportedly signed the

ballots Yas present.

She ras told by the notary that ln order for the

ballots to be 1ega11y notarizecl the personB eigning the

ballots had to be present.

Although the notary publie testified petitioner vent

u,ith him to Pickens County to assist hin 1n talking to

the persons who a1IegedIy signed the balLote, thie uas

after the ballots had already been cast on Septenber 25,

1979. ,

The ballots had been brought to the notaryrs office

by petitioner and co-defendant Julia Hilcler, and before

bringing the ballots to his office, petitloner hacl

telephoned the notary about notarizing the bal1ots.

At least two of the ballots notarized on this

occasion bore forged signatures -- that of l,uci1le Harris

and.{hat of Sophia Spann. Petitioner had talked vith }Is.

Spann about voting an absentee bal-Iot, but Ms. Spann told

her she voted at the po11s.

0n Sepgember 25, 1978, vhen co-defendant .Iulia

Wilder depcsited the 39 absentee ballots at the cireuit

clerk's offiee, petitioner aeeompanied Julia Uilder to

the courthouse; and the evidence Yas clear Julia Wilder

caused at least two forged ballots to be east as her

choiee for a single candidate.

tt"

''

Thus, there yaB ampLe eviilence fron yhleh the Jury

could reagonably eonclude that petltioner partlelpated 1n

a eehene vlth Julia wllder to cast at least two forgedt

absentee ballots for a single office in the run-off

e lect i on.

Under Alabama

and co-eonspirators

indietetl and tried

$ t r-9-1 .

1aw, aecompllces, aiders

in the comnission of a

as prineipals. Alabama

and abettors,

felony, are

Cocle 1975,

The evidence then clearly supporte petitionerrs

convietion under Count Tw ndi

Under f ssue g( t ) , BS denomirrated in petitioner's

"response," petitioner complains the indictment was

eonst:'uctively amended by the trial eourt's jury

inst{uctions which ineluded instruetions pertaining to

four other s'r,atutes than the one under vhich petitioner

was i nC i eted .

No objection whatsoever uas nade at trial to the

trial eourtrB oral charge. lhus, Do issue concerning

constructive amendnent or erroneous jury instructions

coul-d have been raised in the Alabana Court of Criminal

Appeals. Brazell v. State, 421 So. Zd,321 (Afa. Crin.

App. 1982). And this procedural dlefault on this issue

forecloses consideration of these clains on the nerits

l f:-'b:.€

&

1n

a federal habeas proeeecling.

u.s. 72 (rg??).

I{ainwrigLt y. Sykes, 4r,

As to fssue B(2) es denorninated in petitionerrs

"response," respondents defer to the reasoning antl

authority citecl by the Court of Crininal Appeals that

indictnent was constitutionally adequate to appriee

petitioner of the nature of the charges agalnst her.

Issue C -- because no objection to the trlal pourtrs

oral eharge was rnacle at trial, the merits of petitioner I s

claim 1s forcloeed in a federal habeas proeeecllng.

Brazell v. State, supra; Wainuright v. Sykes, Bupra.

fssue D in the Iresponse' is another conplaint about

the trial courtr6 instruetions i.e., that the trial

court's instructions ancunted to presenting I 17-21-1 and

$ th5-115 to the jury as strict liability offenses.

Again, no such objeetion was raised to the trial courtts

instruction by petitioner. Eenee, petitioner may not

raise the matter noh'in a federal habeas proeeeding.

3raze11 v. State, aupra; Uainyright v. Sykes, Bupra.

Issue E in the Iresponse" is that petitioner uas

convieted for her participation in eonduet protected by

the Voting Rights Aets, and protected by the First,

Iourteenth, and Fifteenth Anendments. Respondents do not

5

believe these laus protect a pereon rho votee twiee tn

the 6ame eleetion for the sg'ne off ice ln violatlon of

state 1-av by castlng forged absentee ballote purporting

to be the absentee ballots of registered voters.

In Issue F, petitloner contends that Coile $ 17_2r_1

is unconstitutionally vague and overbroad on lts face in

that it does not provide fair notice of the concluet

prohibited. ,

It is well established that vagueness cha1lenges to

statutes vhieh clo not involve First Amendnent freedons

must be exarained in the light of the faets of the case at

hand. United States v. Mazurie, 419 U.S. 544 (tgZf).

Although petitioner makes some assertions about her

activities in a11eged1y aiding elderly blacks to vote

being within the purview of Iirst Anendroent protections,

it is cLear the statute under which she yas convicted

does not reaeh such aetivities. The statute prohibits

easting more than one baIlot for a single office in a

given election. f'urthermore, the statute clearly gives

notice that yhat petitioner did uas prohibited under the

particular facts proved at trial she eaused at least

two forged ballots to be cast for her choice for U.S.

Senate demceratlc candidate in the run-off election.

*tot s 2)

ffi q01 S7d

lb+ (nb^bCI^&a 5 0. \

l 5 l

,-\uAl)uu ruLtr.- J \-\ )

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

E'OR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABA!44

II{ONTGOT.TERY DIVIS ION

-x

MAGGIE S. BOZEMAN, '

Petitioner, i Civil Action No. 83-H-579-N

- against :

EALON M. LAMBERT, JACK C. LUFKIN AND :

JOHN T. PORTER IN THETR OFFICAL

CAPACITIES AS MEMBERS OF THE ALABAMA 3

BOARD OF PARDONS AND PAROtES, AND

TED BUTLER, A PROBATION AND PAROLE 3

OFFICER, EMPLOYED BY THE ATABAI{A

BOARD OF PARDONS AND PAROLES, 3

Respondents. :

:

--x

PETTTIONER I S I{EMORANDU!{ OF LAW

IN SUPPORT OF MOTION FOR SUMMARY JUDGMENT

I

TABIE OF CONTENTS

PRELIIIIfNARY STATEMENT ... .. .. .. o. . . ... . .. . ' "

I. SU}IMARY JUDGMENT IS AN APPROPRIATE

PROCEDURE ......... " o " " " " ""' o " ""'

II. THE EVIDENCE WAS INSUFFICIENT TO CONVICT ..

A. The Elements of the Offense ...... o. '

B. The Evidencg at Trial .. o........... o '

C. The Jackson v. Virginia Standard "' "

III. THE INDICTMENT WAS FATALLY DEFECTIVE ......

A. The Indictrnent Failed to Provide Fair

Notice of ALI of the Charges on Which

to the JurY Was Permitted to Return

a Verdict of Guilt -. ....... . o. o. .. ' " 1 I

B. The Indictment Failed to Include

Sufficient Allegations on the Charges

of Fraud ............"..""""""' 28

( 1 ) The factual allegations in each

Count were insufficient ......... 29

(2) Necessary elements of the crime

were not alleged ....... ......... 34

IV. PETITIONER WAS SUBJECTED TO EX POST FACTO

TIABIITITY............."""""" 36

V. PETITIONER WAS CONVICTED ON STRICT

LTABILITY GROUNDS ............... -. o o...... 41

Page

1

3

4

5

6

't3

17

1-

\

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT

petitioner Maggie s. Bozeman was convicted on a three

count indictment of a single undifferentiated violation of

Alabama Code S l7-23-1 (1975) and sentenced to a perioo of four

years in the penitentiary. She is currently on parole in the

custody of respondent members of the State Board of Pardons and'

Parole. The judgment was appealed to the Court of Crininal

Appeals of Alabama, which affirmed the conviction on March 3'l ,

1981, Bozeman v. State, 401 So.2d 167. The Court of Criminal

Appeals denied a motion for rehearing of the appeal on April

21, 1981. On July 24, 1981 the Supreme Court of Alabama

denied a petition for writ of certiorari to the Court of

Criminal Appeals. 40l So.2d 171. The Supreme Court of the

United States denied a Petition for writ of certiorari to the

Court of Criminal Appeals on November 16, 1981. 454 U.S.

r058.

The instant federal habeas corpus proceeding was initiated

by the filing of a Petition for a Writ of Habeas Corpus (herein-

after nPetition") on June 8, 1983. This memorandum of law is

submitted in support of petitioner's motion for summary judgment

on four issues raised by her Petition:

1. Thatr €ls alleged in paragraph 16 of the Petition, the

evidence offered at trial was insufficient to prove her guilty

beyond a reasonable doubt in violation of her Due Process rights

as construed in Jackson v. yilg-inia, 443 U.S. 307 (1979).

2. Thatr ds alleged in paragraPhs 19-21 of the Petition,

the indictment, charging pet,itioner with violating S 17-23-1

rras insufficient to inform petitioner of the nature and cause

of the accusation against her, as required by the Sixth and

Fourteenth Amendments .

3. Thatr ds alleged in paragraph 24 of the Petition,

the instructions to the jury impermissibly broadened S 17-23-1,

so as to create ex post facto liability in violation of the

Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

4. Thatr ds alleged in paragraph 25 of the Petition, the

instructions perrnitted petitioner to be convicted on the basis

of strict liability in violation of the Due Process Clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment.

2-

SUMMARY JUDGUENT IS AN APPROPRTATE PROCEDURE FOR

ADJUDICATING SOME OE PETITTONERIS CLAIMS

RuIe 11 of the Rules Governing Section 2254 Cases in the

United States District Courts provides that nIt]he Federal Rules

of Civil Procedure, to the extent that they are not inconsistent

with these rules, may be applied, when appropriate, to petitions

filed under these rules.n The Supreme Court of the United States

has specifically held that Fed.R.Civ.P. 56, the rule providing for

summary judgment, is applicable to federal habeas corPus proceed-

ings. EfggEfgggg v. Allison, 431 U.S. 53, 80-81 (L977)i see

also Wright, Procedure for llqbeas Corpus, 77 F.R.D. 227 | 228

(1e78).

There can be no genuine issue as to any material fact relat-

ing to petitioner's claims which are the subject of this Motion

for Summary ,Iudgment. The only facts involved in those claims

are the evidence submitted to the jury, the indictnent and the

instructions to the jury. Those facts are reflected in the cer-

tified transcript of the trial proceedingsr submitted on Septem-

ber 2L, 1983 by respondents as Exhibit "I.n Accordingly, peti-

tioner's claims as set forth in paragraphs L6, L9-21, 24 and 25

of her Petition and as briefed belowr Iniy be decided soIeIy as

questions of law and are appropriate for adjudication by

1/

summary j udgment.-

7/ If this Court is unable to determine that petitioner should

prevail as a matter of law on the clairrrs in Paragraphs L6, L9-21 |

24 and 25 of her Petition, petitioner does not waive her right

to present additional evidence on these and other claims. Peti-

tioner is simply asserting that on the basis of the pleadings

and the present state of the record, she is entitled to prevail

as a matter of law on Ehe clalms briefed herein.

3-

rI

PETITIONERIS CONSTITUTIONAL RTGTITS WERE VIOLATED

IN THAT THE EVIDENCE WAS INSUFFICIENT TO PROVE

EACH ELEMENT OF THE OFFENSE CHARGED

Based on the evidence offered at trialr rlo rational jury

could have found that each of the elements of the offense

charged was proved beyond a reasonable doubt. Petitioner's

conviction therefore violated the Due Process Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment as construed in Jac@, 443

u.s. 307 ( 1979).

Petitioner's conduct during the Democratic Primary Run-off

Election of September 26, 1978 (hereinafter nrun-off") as estab-

lished by the evidence, considered in the light most favorable

2/

to the prosecutionr w6S neither shown to be fraudulent nor in

violation of each of the elenents of Ala. Code 517-23-1 (1975),

the only statute charged in the indictment. To demonstrate this

contention, petitioner wilI first set forth the elements of

Z/ Under Jackson v. Virqinia the evidence of record must be

reviewed "in the light most favorable to the prosecutionr' Id.

at 319. This process requires the federal habeas court to

draw 'reasonable inferences from basic facts to ultimate facts"

in a manner favorable to the prosecution. Id. It also

requires that when the evidence establishesThistorical facts

that support conflicting inferences [the federal habeas

courtl must presume -- even if it does not affirmatively appear

on the record -- that the trier of fact resolved any such

conflicts in favor of the prosecution.' Id. at 326. Eurther-

more, in ruling on the sufiiciency of theTvidence "a11 of the

evidence is to be considered.n Ia. at 319 (emphasis-EEFEd-f.

T-Ee evfrIence must be assessed inTigfrt of the elements oi

the crime charged, and the federal habeas judge must then

determine whether any rational jury, properly instructed, could

have found petitioner guilty beyond a reasonable doubt of each

element of the crime charged. Id. at 317-319.

-4

S 17-23-1, second she will summarize the evidence presented at

trialr and third she will apply such evidence in accordance with

Jackson to show that no reasonable jury could have convicted

her beyond a reasonable doubt of violating S 17-23-1.

A. The Elements of the Offense

Section L7-23-L provides:

Any person who votes more than once at any election held

in-this stater oE deposits more than one ballot for the

same office as his vote at such election, or knowingly

attempts to 6tE-wtr6-ne is not entitled to do so, or is

guilty of any kind of illegal or fraudulent voting, must,

on conviction, be imprisoned in the penitentiary for not

less than two nor moie than five years, dt the discretion

of the jury. (Emphasis added. )

The elements of the offense against petitioner are that she

ott

L7-23-L I

employed fraud to vote more than one ballot as her vote,

with the same menq rea required for culpability under S

aided and abetted one or more accomplices to vote more than one

ballot as their vote.

Although the statute on its face includes broad and open-

ended provisionsr and fails to specify in each of its provisions

a level of mens rea which must be proven in order to convict,

some clarification in the terms of the statute has been provided

by the Supreme Court of A}abama. In Wilson v. State, 52 AIa.

299 (1875), the Court held that "[t]he offense denounced by the

statute ... is voting more than oncern E. at 303. According to

Wilsonr then, all of the provisions of the statute including

the prohibit,ion against 'any kind of i1Iegal or fraudulent voting"

in fact state just one broad prohibition against the casting of

more than one vote by an individual at a single election.

5-

In Wilson the Court also stateo that public exposure of

otherwise secret ballots is permitted only when necessary to pre-

3/

vent frauOi=' aS a result, fraud is a necessary element of the

offense in a prosecution under S 17-23-1 when the Staters evi-

dence is predicated upon the opening of ballots. Id. Since the

State in the present case intro<iuced 39 ballots into evidence,

Tr.41, and inspected numerous other ballots as part of its inves-

tigation, Tr. 31-33, it was required at minimum to prove fraud on

4/

petitionerts part in order to convict her under S 17-23-1.-

B. The Evidence at Trial

The three count indictrnent filed against petitioner charged

that she violated S 17-23-1 through her alleged voting in the

1/ "[I]t is only when.it may be_necessary for the prevention

oi fraua, or the -induction inlo office of one not teally

elected by qualified voters, that an inspection of the ballot

can be had.'t Wilson v. State, 52 Ala. at 303.

lt Analogously, proof of crininal intent is required under

Sther elabima s-tatutes which prescribe penalties for voting

abuse. In Associateo In<iustdes of Alabqma. Inc. v. StPte, :11

So.2d 87g ( ere-Eilarged

with violating A1a. Code S 17-22-15 (1975), the Corrupt

Practices Act, which like S '17-23-'l is without an explicit

intent element. lhe Court construed the Act to require proof

of willful misconduct as a Prerequisite for liability. See

also Ala. Code S 17-l o-17 'lgaz jupp. ) (penalizing wittful

lEratlon of an absentee ballot so that it does not reflect

the voter's choice); Ala. Code S 17-4-139 (1982 Supp.) (penaliz-

ing one who knowingly registers to vote in a manner contrary to

f ai); A1a. Code t 7--A-a1- ( 1975) (penal LzLng willfuI deception

of voters by voting officials Providing assistance in baIlot

preparationl . The Alabama Court of Criminal Appeals in i'[ilder

;. state, 401 So.2d I51, 159-150, (Ala- Crim. APP.lr.cgr!'

aenleiliOf So.2d L67 (AIa, 1981) , cgr!. denied , 454 U.s. 1057

lJ$!lI; aiscussing the intent elemeiffi 5-7173-1 stated that

i[t]f," words 'i1l6ga1 or fraudule1t', as used in tS 17-23-11

aie merely clescriptive of the intent necessary fo! the commis-

sion of the offenie." Wilder v. Stater guPE&7 401 So.2d at

159-160. This specif icEffin--of ifEgaf ffint as an alternative

to fraudulent inlent, although it has never been sanctioned by

the Alabama Suprerne Court, is consistent with requiring a high

leve} of mens rea -- i.e., the specific intent to commit an

rllegality - for conviCtron under S 17-23-1.

5-

run-off. At trial the prosecution introduced 39 absentee

ballots into evidence, TE. 41, and clairned that petitioner had

participated in the voting of those ballots in violation of S

L7-23-1. It was undisputed that each ballot had been cast in the

run-off, and purported to be the vote of a different black

elderly resident of Pickens County.

No evidence was presented that petitioner had cast or

participated in the casting, the filling out or the procurement

of any.of the thirty-nine absentee ballots. Indeed there is

nothing in the record to indicate who cast those ballots , Ir.

21. The transcript is also silent on whether petitioner voted

even once in any manner in the run-off.

The prosecution hinged its case on evidence which showed

that petitioner may have played a minor role in the notarizing

of the 39 absentee ballots, and contended that petitioner's role

in the notarizing was sufficient evidence to warrant her

conviction under S 17-23-1 | because the voters did not aPpear

before the notary. Tr. 195-197i cf. Tr. 90, 105-106. District

Attorney Johnston, in his resPonse to petitionerrs motion for a

directed verdict made at the close of the State's case, claimed

that the thirty-nine absentee ballots 'were not properly notar-

ized, and in thaL sense, they were fraudulent.' Tr- 196. Then

he stated that'rthe act of the Defendant in arranging the confer-

ence Iat which the ballots were notarized] and in participating

in the presentation of the ballots to lthe notary] to be

notarized was fraud.n Tr. 196.

7-

The prosecution ca1led only nine of the thirty-nine

absentee voters to testify. Each of these witnesses h'as

elderly, of poor memory, illiterate or semiliterater dnd

lacking in even a rudimentary knowledge of voting or notarizing

procedures. Their testirtony aS a result was almost uniformly

confusing and conflicting and often fariored both the prosecution

and the defense depending on which was examining the witness.

Nevertheless, insofar as any synthesis can be made of the

individual testimony, it will be construed in the light most

favorable to'the prosecution. Three of the nine voters, lrls'

Sophia Spann (Tr. 179) | Ms. Lucille Harris (Tr. 189), and I'!s'

Maudine Latham (Tr. 91-93), testified to never having seen the

absentee ballot introcluceO into evidence as their vote' MS'

Anne Billups (Tr. 97-98), lts. ilattie Gipson (Tr. 110) ' Ms.

Janie Richie (Tr. 127') , and Ms. Fronnie Rice (Tr. 136-137, 1481

151) each remembereo voting by absentee ballot in the run-off'

Neither i{r. Nat Dancy nor I'ls. Lou Sommerville provide<i any

coherent testimony whatever on the way in which they voted in

the run-off.

It is uncontested that only two of these voters, lts' Sophia

Spann and Ms. Lou Sommerville, gave evidence of any contact with

petitioner regarding absentee voting. (Prosecution'S closing

argument at 26, filed with this court, Nov. 30' 1983). No

connection was drawn even by these voters between petitioner and

any of the absentee ballots cast in the run-off'

8-

Ms. Spann testified that petitioner had contacted her on

one occasion about absentee voting in general. Tr. 180, 184. But

she was unclear as to what was discussed on that occasi.on. Twice

Ms. Spann t,estified that Petitioner spoke to her at a time when

no election was being held, and that petitioner asked her whether

she would be interested in voting by absentee ballot in a future

election. Tr. 180, 184. But at another point in her testimony

!1s. Spann stated that petitioner visited to ask Ms. Spann if she

had voted in an election which had recently taken Place. Tr

182. Regardless of which version is true, and despite Ms.

Spannrs uncertain memory which makes an accurate reconstruction of

their meeting lmpossible, it is plain that her testimony in no

way linked petitioner to the absentee ballot voted in t'ls.

Spannrs name in the run-off at issue in the indictment. As the

evidence related above shows, P€titionerrs contact with Ms.

Spann began and ended with mere discussion between the two

life-long friends, Tr. 179-180, pertaining generally to voting.

The only evidence adduced from lls. sommerville which

connected petitioner with Ms. Sommervillers absentee voting

was introduced by the prosecutorrs reading to the

jury notes purporting to be the transcript of an out-of-court

interrogation of Ms. Sommerville conducted without an attorney

present for either the witness or petitioner.I/ ,."aifying

2/ This and similar transcripts were never shown to petitioner,

End were not taken pursuant to established Alabama procedures

for pre-trial depositions. They were allowed to go before the

jury-as substantlve evidence in violation of petitioner's

9-

in person, Us. SommerviLle vehemently challenged the veracity

of the out-of-court statements, and steadfastly denied that

petitioner was involved in any way with her voting activities.

Tr. 161r 169r 173, 174t 175. According to the out-of-court

statements petitioner aided lls. Sommerville to fiLl out an

application for an absentee ballot in order that ils. Sommerville

could vote by absentee baIIot in the run-off, Tt.161t 159.

The prosecution also informed the jury through the out-of-

court statements that petitioner aided Ms. Sommerville in fill-

ing out an actual absentee balIot, Tr. 173-174. But according

to that part of lts. Sommerville's out-of-court testimony, as

read by the prosecution, she instructed petitioner in filling

out the absentee ballot to mark votes for one Reverend Porter

and Pickens County Sheriff Louie Coleman, TE. 174' Neither of

these tr{o men were candidates in the run-off; both were candi-

dates in the regular primary which had taken place on september

5, 1978. This fact was established for the jury during the

cross-examination of Ms. Sommerville, Tr. 176-177. Therefore,

the absentee ballot described in the out-of-court statement as

having been prepared with petitioner's help could not have been

the absentee ba11ot filed in Ms. Sommerville's name in the

1/ continued

constitutional rights as alleged in paragraph 26 of the Petition.

Since the issue piesented by paragrapn 26 requires an evidentiary

hearing and is therefore not encomPasssed within the present

motion for sumlnary judgmentr w€ asiume for present purposes th9

aamissioility of ns. Somerville's out-of-court st,atements. only

should the piesent motion fail would it be necessary for the

court to reach paragraph 26, and then to reconsider petitioner's

Jacksoq v. lrifgiqt_A-c:-lim with the offending evioence excluded.

See-note t, qgpf.e.

10

run-off. In any event, all of the evidence adduced from the

statements, taken in the light most favorable to the prosecution,

showed no more t,han that petitioner aided Ms. Sommerville to

engage in 1awful voting activities with the latterrs knowledge

and consent.

The only manner in which the prosecution drew even the

most attenuated connection between Petitioner and the 39

absentee ballots introduced by the State at trial was through

the tbstimony of Mr. PauI Rollins, a notary Public from

Tuscaloosa. Mr. Rollins testified that he notarized the

thirty-nine ballots in his office in Tuscaloosa without the

voters being present. Tr. 56-64. Mr. Rollins testified that

petitioner, with three or four other women, was Present in the

room when he was notarizing the ballots. Tr. 57. But Mr.

Rollins denied that Petitioner Personally requested him to

notarize the baltots. Tr. 59, 60, 62, 64. He also stated that

he had no memory of Petitioner rePresenting to him that the

signatures on the ballots were genuine. Tr. 73-74. A11 the

prosecution could elicit from Mr. Rollins was that petitioner

and the other women Present at the notarizing $rere "together'"

Tr. 50-61, 62, 64, 71. The prosecution thus failed to present

any evi<ience that petitioner had done anything more than to be

present when l,tr. Rollins notarized the absentee ballots. No

evidence rrras presented to contradict lr{r. Rollins' unequivocal

answers denying actual involvement by petitioner in his notariz-

ing of the ballots in the voters I absence.

11

The prosecution used an out-of-court statement attributed

to Mr. RoIl inr[/ to introduce evidence that petitioner had

telephoned ltr. Rollins to request that he notarize the absentee

ballots in question, Tr. 65-55. Mr. Rollins in his in-court

testimony could not remember whether petitioner had made any

such request. Tr . s7, 64, 65-66, 76-77.!/ ,o*"ver, even

considered in the light most favorable to the state, the

evidence on the Eelephone call establishes nothing beyond a

mere request by pet,itioner for Mr. Rollins' notary services.

It does not establish that petitioner was responsible for

suggest,ing or arranging the time, place, or details of the

notarization, nor that petitioner played any part ln the

decision that the notarizing take place in !1r. Rollinsr office

vrithout the voters present. Mr. Johnston'S contention that

petitioner 'arranged the conferencen at which the ballots were

notarized, Tr. 196, is simply not supported by the evidence'

Nor is his argument that Petitioner "participat led] " in the

notarizing, .!1]., Lf this means anything more than that peti-

tioner was present while the ballots were notarized' fn short,

9/ri

AS

as

pr

This statement was allowed to go before the jury as substan-

ve evidence in violation of petitioner's constitutional rights

atfegea in paragraph 26 of Lhe petition. We deal with it here

we hive dealt with-t'ls. Somerville's out-of-court statement

esenting similar issues. See note 5 supra'

Z/ He testified in person that he received two telephone

6alls prior to his noiarizing the ballols. Tr. 76. IIe stated

that ti:e first such call was from petitioner but could remember

noitring of the substance of that conversation except that it

'pertaintedl to ballots.o Tr. 76-77. The second telephone

c6nversaiion, he recalled, centered around the same subject,

but he could neither remember the identity of the calIer nor go

into any further detail on the substance of the conversation.

rd.

12

t,he evidence attained from Mr. Ro1lins, when combined with all

the record evidence, remains wholly insufficient under Jackson.

The only other evidence which tied petitioner to even a

general effort to bring out the black vote among the elderly in

Pickens County was given by Janice Tilleyr ill employee in the

circuit clerk's office, who testified that petitioner picked up

"Ia]pproxinately 25 to 30 applications" for absentee ballots

during the week preceding the run-off. Tr. 18. This testimony

about. blank apPlication forms was never tied to any of the 39

8/

absentee ballots allegedIy voted in violation of S 17-23-1.-

Nor did the prosecution contend that there was anything illegal

about petitionerrs conduct in picking up blank application

forms. (Prosecution's closing argument at 3, filed with Court

Nov. 30, 1983).

The Evidence was Insufficient to Convict under Jacksonc.

The testimony of the voters

no evidence of culpability within

and Ms. Ti11ey provides

the elements of S 17-23-1.

9_/ Contrary to Respondent I s contentions in their January 1 0,

Tgga Replyr Ilo witness testified that any of the 39 absentee

ballots rdere cast by petitioner or by anyone known to petit,ioner.

In factr Do evidence was presented that anyone physically

deposited the ballots in the circuit clerkrs offi.ce. Ms. Ti1ley

teitified t.hat she saw petitioner in a car on September 25, the

day before the run-off election, but she testified that she did

noi remember petitioner bringing in any ballots. Tr. 20-21.

Ms. Ti11ey testified that petitioner did not come into her

office that day. Id. A motion to strike Ms. Til1ey's testi-

mony, that while petitioner was in the car, another Person,

Julia Wilderr hlEls in her off ice, was sustained. Id. Even with

the stricken statement, there was no testimony that Julia

Wilder or anyone else possessed or deposited any ballots in the

circuit clerkrs office.

13

',o-<,, - / <11*

between peririoner and the absentee ballots aIlegedly voted i.*e1o 7*l,/betweenpetitionerandtheabsenteeba11otsa1}eged}yvoteclLn"no<

fr^*

violation of S 17-23-1. Considering just such testimony, Peti- '%:L"Z

tionerf s conviction would faII quite clearly under the no-eviden;AA-,,-,

9/ /to a

rule of Thompson v. touisville, 369 U.S. 199 ( 1960).:' Even 'n -<o

4)

under the no-evidence rule the record must contain at least a

'a'<*9

€

modicum of relevant evidence tying petitioner to activities ?;

which could be found to violate each element of S 17-23-1, or

t,he conviction cannot stand. See rleqfEeq v. Virginia, g1L6,

413 U.S. at 370; Vachon v. New Hampshiret 414 U.S. 478 (1974).

The prosecutionts entire case must therefore rest on the

testimony of Mr. Rollins. For his testimony to provide the

the

notarizing and her telephone call to Mr. Rollins as evidence

that she was acting with the intent of committing fraud as Part

of a scheme to enable her or an accomplice to vote more than one

ballot as their vote. Dubious at best under the Thompson rule,

such evidence is woefully insufficient under Jackson to convince

a rational trier of fact beyond a reasonable doubt that petitioner

violated each element of S 17-23-1.

2/ Thomps.on held it to be a violation of due Process totpuni$-E-fran without evidence of his guiIt." 369 U.S. at 205.

tn Jackson v.JLEginig, 443 U.S. 307 (1979), the Supreme Court

hef@ test was insufficient to protect the due

process rightsEE-E-aUeas petitioners, and therefore established

the tougher Jackson Standard. ff a conviction fal]s under

Thompson, a fortfori it falls under Jackson.

+

requisite evidence of culpability, it must be possible for

rational trier of fact to view petitionerrs mere presence at

14

Jackson , of course, gives the prosecution the benefit of

all reasonable inferences that can be drawn from basic facts t,o

ultimate facts. Jackson v. virginia, supra, 443 U.S. at 319.

Let us do that here. The only relevant basic facts established

by the evidence hlere those concerning Petitionerrs telephone

call to Mr. Rollins, her presence at the notarizLng, and the

fact that such notari zLng occurred outside of the presence of

the voters. petitioner's conviction cannot sLand unless it is

reasonable to infer from these basic facts that ( 1 ) the notatlz-

ing was part of a scheme, in which prosecution witness Rollins

participated, to employ fraud to vote more than once, and (2)

that petitioner knowingly, with intent to employ fraud in order

to aid others to vote more than once, participated in such

a scheme through her involvement in the notarizLng. Petitioner

contends that such inferences are manifestly unreasonable'

In Cosby v._Jongsr 682 F.2d 1373 (11th Cir. 1982), it was

held that the process of inferring ultimate facts from eviden-

tiary facts reaches a degree of attenuation which falls short

of constitutional sufficiency under {qclgqq "at least when the

undisputed facts give equal support to inconsistent inferences.'

Id. at 1383 n.21. Even if the evidence gives "equa] or nearly

equal circurnstantial support to a theory of guilt and a theory

of innocence of the crime charged, a reasonable jury must

necessarily entertain a reasonable doubtr" and under Jacksqq

the evidence must be deemed insufficient. Id. at 1383. In

petitioner's case, if anything, the circumstantial suPport

given by the evidence to theories of innocence far outweighs

15

10-/

that given to the theorY of 9ui1t.

petitioner's indivldual conduct as revealed by the evidence

adduced from Mr. Rollins was not on its face indicative or even

suggestive of an intent to use fraud in order to vote more than

once. Nor was any of petitioner's conduct as revealed by all

the evidence suggestive in the slightest of culpable behavior.

With no evidence providing reasonable inferential support, the

theory of petitioner's guilt is thus left as a bare theory --

t,o hinge on the purely hypothetical view that petitioner might

have carried out her minor participation in the notarizing with

culpable intent,, which itself is premised on an equally unsupported

hypotheses that the notarizing was a part of a scherne whose end

result was that some Person, unnamed and unknown through the

evidence presented at tria1, might have voted more than once in

violation of S 17-23-I.

10/ that some women involved in the effort to aid elderly blacks

6 vote had the absentee ballots notarized outside of the presence

of the voters is not in itself suggestive of the criminal intent to

cause any voter to vote more than once. Indeed, given the logis-

tics of tfris effort as established by E\F*.Vl{ence at trial and

the fact that there were no black notariii{fin*Pickens County, in

order to have had each ballot notarized in'the presence of the

voter as the voter marked t,he ballot, the women would clearly have

needed a notary at their continual service, ready to travel

throughout pickens County. Thus the action of the women in having

the Uiltots notarized in-Tuscaloosa was completely consistent with

a good faith, constitutionally protected, effort to aid elderly

blicks to vote. fn addition, it is significant that the Alabama

legislature subsequently abolished any requirement that absentee

ballots be sworn to before a notary, S 17-10-6 and S 17-20-7

(Acts 1980, llo. 80-732t P. 1478, SS 3 and 4.)

15

It is impermissible and unreasonable to use such weak and

inconclusive factual suPPort as a "base uPon which to pile

inference on top of inference to reach beyond reasonable doubt

to the ultimate conclusion.o Hollowav v. McElrovt 632 F.2d

605, 641 ( 5th Cir. 1980), cert. @, 451 U.S. 1028 ( l98l ).

Nor can inferences be based on nmere conject,ure and suspicion"

and still be reasonable. United States v. .Fitzhanis, 533 F'2d

416t 423 (5th Cir. 1980)(applying Jackson). After considering

aII of the evidence ad<iuced at trial in the light most favorable

to the prosecution, a reasonable jury would perforce harbor a

reasonable doubt as to whether petitioner had violated all the

necessary elements of s 17-23-1. Petitioner's conviction was

therefore obtained in violation of her rights under the Due

Process Clause of the Fourteenth Anendment'

III

PETITIONERIS INDICTMENI WAS FATALLY DEFECTIVE

INTHATITFAILEDToINFoRMHERoFTHENATURE

AND CAUSE OF THE ACCUSATION AGAINST IIER

The indictment filed against petitioner failed in numerous

respectsr ES alleged in paragraphs L7-2L of the Petition, to

provide the leve1 of notice required by the sixth Amendrnentrs

guarantee that in all criminal cases the accused shalI receive

"notice of the nature and cause of the accusation" against her.

Each of these failures, standing alone' amounts to a denial of

constitutionally required notice, while together they add up to

a stunningly harsh and egregious denial of noticer EI Eight which

17

the Supreme Court has deemed nthe first

recognized requirement of due process.n

As

statutes

provided

that the

ing that

i1 legaI

and most

Smith v.

universally

OrGradyr 3ll

333 U.S. 196,U.S. 329, 334 (1941); see also CoIe v. Arkansas,

201 (1948).

As alleged in paragraph 19 of the Petition, a number of

charges were subnitted to Ehe jury for which the indictment

failed to provide any notice. This failure constituted a denial

of the right to notice of each such charge and the offenses

contained therein. See subsection (A) below. As alleged in

paragraphs 20 and 2L of the Petition, the charges of fraud in

the indictment were deficient in two respects. They failed to

make constitutionally adequate factual allegations of such

fraud, and they failed to charge each of the elements of such

fraud in a manner sufficient to meet constitutional notice

requirements. See subsection (B) below.

P-e-t-i-t-1o-qe-r-'-s- iq4.tq.Uqe-qt--w-qq.-!gt-11}v defective in that'-!t'

lAf-te-Qje-PEqY.f.qe. -!qtr- -qo-t-lg.q.-qf-e11 of q1q-eb1r-g.e.F-_9.q-q!rch.

h.e.r--iqff-E€=pe.ryitteo to return a veri.iq!-q!-gq.t1-!.

A.

is set forth in paragraph 19 of the Petition, various

and theories of liability as to which the indictment

no notice whatsoever were incorporated into the charges

jury was instructed to consider as the basis for a find-

petitioner had violated S 17-23-1 by "any kind of

The indictment filed against petitioner

18

... voting. "

is set forth in paragraph 18 of the Petition and at Tr. 2'11 |

Exhibit 'In of Respondentts Response to Motion to Furnish

Transcript. In each of its three countsr the indictment ostensi-

bly tracked various provisions of S 17-23-1. It alleged disjunc-

tively with other charges in Count I that petitioner had "vot [ed]

illegaIIy or fraudulentlyr" and in Counts II and III that she

had "cast illegaI or fraudulent absentee ba11ots.o OnIy in

Count III was any factual specification provided; and there it

was alleged that petitioner had deposited fraudulent absentee

ballots which she knew to be fraudulent. In none of the counts

was any elaboration given to that portlon of the charge which

accused petitioner of having nvotIed] iIlegallyn or having ncast

i11ega1 ..o absentee baI1ots."

In his instructions to the jury, the trial judge did frame

elaborate charges under which petitioner could be convicted of

illegal voting. After reading S 17-23-1 to the jury, he

explained the statuters provision against oany kind of iIIega1

or fraudulent voting" by defining the terms "iIlegaI" and

"fraudulent.n Tr. 201. Concerning the term "illega]ro the

jury was instructed that ni]legal, of course, means an act that

is not authorized by law or is contrary to the la!r." Tr. 20I.

The clear import of this instruction was that s 17-23-1rs

prohibition against nany kind of i}}egal ... voting" included

any act found to be 'not authorized by 1aw or ... contrary to

the law." The violation of the letter of any law in the course

of voting activities would require conviction under S 17-23-1 as

19

a ',kind of illegal ... voting." The trial judge then instructed

the jury on four st,atutes: A1a. Code S 17-'10-3 (1975) lmiscited

by the judge as s 17-23-31, Tr. 2o2i AIa. Code 517-10-6 (1975)

[miscited by the judge as S 17-10-7lt Tr. 202i AIa. Code S

17-10-7 (1975), Tr. 203-204i and AIa. code s13-5-115 (1975), Tr.

204-205. None of these statutes or their elements was charged

against petitioner in the indictrnent. Their terms provideo

numerous new grounds not alleged in the indictment on which to

convict. The jury was thus authorized to find petitioner guilty

under s 17-23-1 if she had acted in a manner'not authorized by

or ... contrary tO" any single provision of any one of a number

of statutes not specified or even hinted at in the indictment.

The following Paragraphs sumrnarize certain of the provi-

sions of the four statutes, and thereby illustrate some of the

grounds for Iiability of which the indictment provided no notice:

The jury was first instructed on s 17-10-3, miscited by the

trial judge as S 17-23-3, which sets forth certain qualifications

as to who may vote by absentee ballot. The trial judge inst'ructed

that under s 17-10-3 a person is eligible to vote absentee if he

will be absent from the county on election day or is afflicted

with ,'any physical illness or infirmity which prevents his attend-

ance at the polls.n Tr. 202. Thus a finding by the jury that

one of the absentee voters had not been physically "prevent [ed]'

from going to the polls to vote in the run-off would have

constituted the finding of an'act not authorized by... or...

contrary ton S 17-10-3, necessitating petitioner's conviction

20

under S 17-23-1 even though petitioner was given no notice in

the indictrnent that such proof could be grounds for liability.

The trial judge then instructed the jury that s 17-10-6,

miscited as S 17-10-7, reguires, iglgE aIia, that all absentee

ballots "shaIl be serorn to before a notary publicn except in

cases where the voter is confined in a hospital or a similar

institution, or is in the armed forces. Tr. 203. Further,

under S 17-10-7, the trial judge stated that the notary must

swear that lhe voter opersonally appeared" before him. Tr.

203. Accordinglyr the evidence that the voters were not present

at the notarizing, see Tr. 56-64, sufficed to establish per Se

culpability under S 17-23-1, although, againrthe indictment gave

petitioner no warning whatsoever of any such basis for culpabil-

11/itv. _-

The trial judge then instructed the jury that s 13-5-115

provides:

"Any person who shall falsely and incorrectly make any

sworn statenent or affidavit aS to any matters of fact

required or authorized to be made under the election laws,

generalr pEimary, special or local of this state shall be

guilty of perjury. This section makes it illegal to make a

Sworn staternent, oathr oE affidavit as to any matters of

fact required or authorized to be made under the election

laws of this state."

Tr. 204. Both sentences of this instruction contain egregious

misstatements concerning S 13-5-115. The first sentence rePre-

11/ It is noteworthy that ss 17-10-6, 17-10-7 were amended

Jeveral months after petitioner's trial by Acts 1980, No.

8O-732t p. L478r SS 3, 4t and no longer require notarization of

the balIot.

21

Sents a verbatim reading of S 13-5-115 with one crucial error.

The trial judge instructed that S 13-5-115 proscribes "falsely

and incorrectly" making the sworn statements described in the

statute, when in fact the statute proscribes the making of such

statements "falsely and corruptly'! -- i.€., with criminal intent.

The second sentence of the instruction, which apparently repre-

sents the trial judge's interpretation of S 13-5-115, has the

absurd result of making ilIegaI every sworn statement duly made

under the election laws.

frrespective of these misstatements, the charging of S 13-5-115

deprived petitioner of constitutionally required notice. The

misstatements of the terms of a statute which petitioner had no

reason to suspect she was confronting in the first place only

aggravated this denial of due process. It also constituted a

separate and independent denial of due process as alleged in

paragraph 24 of the Petition .Y/

The indictment contained no allegations which could have

put petitioner on notice that her participaEion in the notarizing

process was violative of S 17-23-1 or in any vray criminal. Three

of the four statutes not charged in the indictment but submitted

L?/ The trial judge also misread s 17-23-I in a way which

dipanded the chlrges against petitioner: He instructe<i the jury

tnit S 17-23-1 penalizes one who "deposit,s more than one ballot

for the same oftice.n Tr. 201. In fact S 17-23-1 penalizes one

who "deposits more than one ballot for the Same office as his

ygq._,' ilmpnasis added). This omission by the trial judge-r;aicil-

fi*Cfranged the meaning of the statute so that the mere Physical

act of depositing two or more ballots at the same election --

even ballots deposited on behalf of otl"rer voters violates S

17-23-1. It thus proOuced a new charge against petitioner of

which tfue indictment provided no notice, since the indictment

had recited the relevant portion of S 17-23-1 accurately.

22

to the jury as a basis for conviction under S 17-23-1 made

petitioner's minor participation in the notarizing into grounds

of per se culpability. At trial a large part of of the prosecu-

tion's case was spent attempting to prove through the testimony

of Mr. Rollins, and through questlons posed to virtually all of

the testifying voters, that the notarizing took place outside of

the presence of the voters and that petitioner in Some way

participated in that notarizing. Hence, the charges made for

the first time in the instructions provided new grounds for

culpability which were crucial to petitioner's conviction. The

failure to aIlege these grounds in the indictment violated

petitioner's rights under the Sixth and Eourteenth Amendments.

The violation was all the more significant because evidence of

the proper elements of the one statute charged in the indictment

was insufficient or nonexistent.

The only relevant allegations in the indictment were that

petitioner had 'vote lrl] illegally" (Count I ) or had ncast illega1

absentee ballots" (Counts II and III) in the run-off. These

allegations in no way informed petitioner with particularity

that she could be prosecuted under the rubric of illegal voting

fOr acts "n6t authorized by ... Or o.. cOntrary tO" the four

unalleged statutes charged in the instructions. But 'notice, to

comply with due process requirements must be given sufficiently

in advance of the scheduled court proceedings so that reasonable