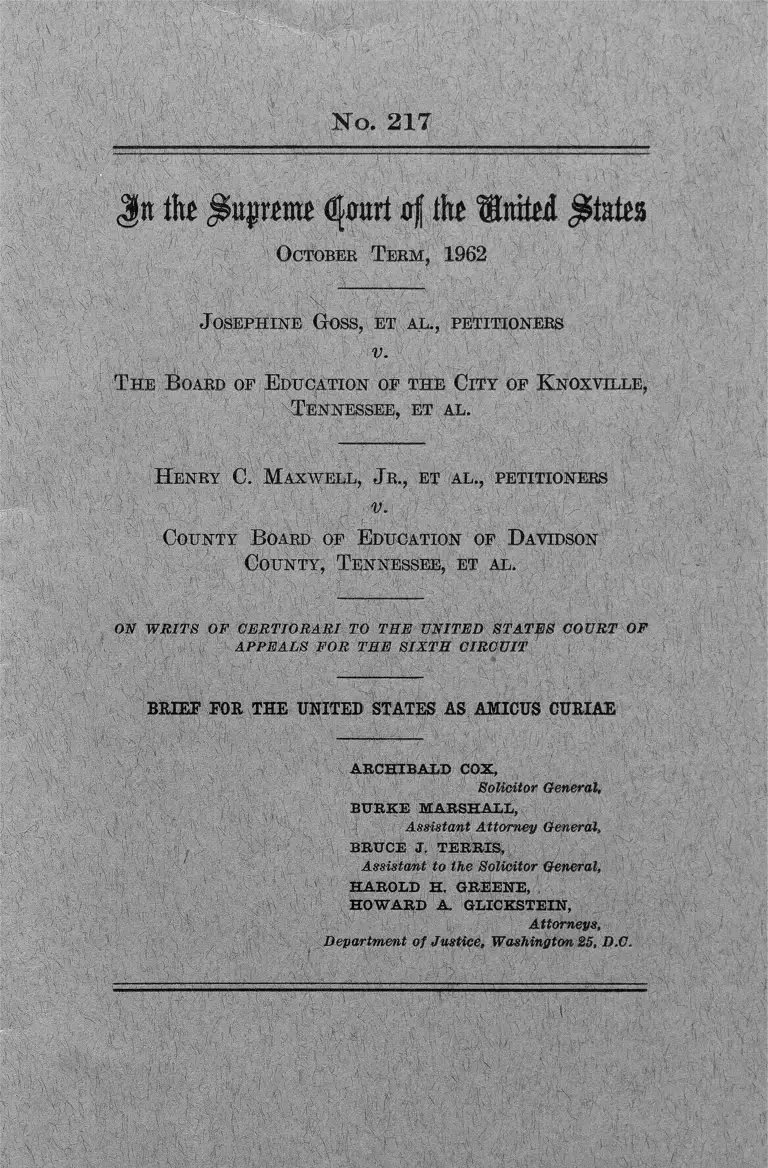

Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Brief Amicus Curiae, 1963. ac07b0fc-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/56143fe2-6897-4cd7-9a53-d9537ef49918/goss-v-knoxville-tn-board-of-education-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

N o. 217

<gn tlit jsupumt fljaurt a | to United States

October T eem, 1962

T he

J osephine Goss, et al., petitionees

v.

of E ducation of the City of K noxville,

1 T ennessee, et al.

H enry C. Maxwell, J r., et al., petitioners

p.

County B oard of E ducation of D avidson

County, T ennessee, et al.

ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

m

ARCHIBALD COX,

Solicitor General,

BURKE MARSHALL,

Assistant Attorney General,

BRUCE J. TERRIS,

Assistant to the Solicitor General,

HAROLD H. GREENE,

HOWARD A GLICKSTEIN,

Attorneys,

Department of Justice, Washington $5, D.O.

vi.;;

I N D E X

Pags

Opinions below__________________________________________1

Jurisdiction__ _ ________________ _v______________ ; 2

Question presented______________________________ :__ 2

Interest of the United States____________ 2

Statement________________________________________ 4

Summary of argument__________________ 15

Argument_____________________ 18

A. The plan of pupil transfers based solely upon race

violates the equal protection clause of the four

teenth amendment______ 22

B. The plan unlawfully tends to preserve school segre

gation by authorizing automatic self-assignment,

upon explicit racial grounds, to the school at

tended under segregation_ _______________ _ 27

C. Other tested methods are available for securing the

educational and psychological welfare of children

during a period of transition to fully integrated

schools_______ _______________ !___________ 34

Conclusion_____________________________________ 41

CITATIONS

Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750____________________ 22

Boson v. Rippy, 285 F. 2d 43________________ :______ 3, 40

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483__________ 3, 4, 16, 41

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U.S. 294_____________ 4,

15, 16, 19, 20, 21, 24, 27, 34, 35

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715__ 23

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 308 F. 2d 491__ 37, 38

Carson v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724-_ ______ _______ 26

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1__________________ 3, 19, 20, 28, 34

Dawson v. Mayor and City Council of Baltimore, 220 F. 2d

386, affirmed, 350 U.S. 877— ______ - ___ _______ _ 23

Dillard v. School Board of City of Charlottesville, Va., 308 F.

2d 920__________ _______________ — _______ 3

Green v. School Board of the City of Roanoke, Virginia, 304

F. 2d 118_______ _________ _________ — _____ 27

Jones v. School Board of City of Alexandria, 278 F. 2d 72__ 27

Kelley v. Board of Education of City of Nashville, 270 F. 2d

209, certiorari denied, 361 U.S. 924_________________ 3, 11

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, 277 F. 2d 370__ 27

671303— 63------1 d )

II

Mapp v. Board of Education of City of Chattanooga, 203 Page

F. Supp. 843____________________________________ 3

Marsh v. County School Board of Roanoke, Virginia, 305

F. 2d 94________________________________________ 27

McCoy v. Greensboro City Board of Education, 179 F. Supp.

745, reversed, 283 F. 2d 667------------------------------------ 38

New Orleans City Park Improvement Assoc, v. Detiege, 358

U.S. 54_________________________________________ 23

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587_____________________ 23

Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798-------------------------------- 27

Parham v. Dove, 271 F. 2d 132------------------------------------ 26

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537--------------------------------- 22

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1------------------------------------ 24

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham Board of Education, 162 F.

Supp. 372, affirmed, 358 U.S. 101---------------------------- 26

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U.S. 631------------------------ 24

Skinner v. Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535------------------------------ 26

Steele v. Louisville cfe Nashville Railroad Co., 323 U.S. 192__ 22

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303------------------------ 22

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629------------------------- 24

Vick v. County Board of Education of Obion County, 205 F.

Supp. 436_______________________________________ 3

Constitution and statutes:

U.S. Constitution, Fourteenth Amendment___15, 19, 22, 39

28U.S.C. 1331_________________________________ 4

28 U.S.C. 1343_________________________________ 4

28 U.S.C. 2201_________________________________ 4

28 U.S.C. 2202_________________________________ 4

42 U.S.C. 1981________________________________ 5

42 U.S.C. 1983____________________________ 5

Miscellaneous:

Greenberg, Race Relations and American Law----------- 32

1961 report of the United States Commission on Civil

Rights, education____________________________ 32

Report of the United States Commission on Civil

Rights, Civil Rights U.S.A./Public Schools Southern

States 1962________________________________ 9, 12, 32

Rule 23(a), F.R. Civil P ________________________ 4

Statistical Summary of School Segregation-desegrega

tion in the Southern and Border States, published by

the Southern Education Reporting Service (Novem

ber 1962)___________________________________ 3

Wey and Corey, Action Pattern in School Desegre

gation______________________________________ 37

Jn to jSttprm* dfimt 4 to fflmM

October T eem, 1962

No. 217

J osephine Goss, et al., petitioners

v.

T he B oard of E ducation op the C ity of K noxville,

T ennessee, et al.

H enry C. Maxwell, J r., et al., petitioners

v.

County B oard of E ducation of D avidson

County, T ennessee, et al.

ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals

for the Sixth Circuit in Goss (R. 157-164) is reported

at 301 F. 2d 164. The opinion of the United States

District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee

(R. 119-137) is reported at 186 F. Supp. 559.

(i)

2

The opinion of the United States District Court for

the Sixth Circuit in Maxwell (R. 282—284) is reported

at 301 F. 2d 828. The first findings of fact, conclu

sions of law, and judgment of the United States Dis

trict Court for the Middle District of Tennessee

(R. 228-243) are reported at 203 F. Supp. 768. The

second findings of fact, conclusions of law, and judg

ment (R. 269-273) are not reported.

JURISDICTION

The judgment of the court of appeals in the Goss

case was entered on April 3, 1962 (R. 156-157). The

judgment of the court of appeals in the Maxwell case

was entered on April 4, 1962 (R. 281). The petitions

for writs of certiorari were granted by this Court on

October 8, 1962, limited to the first question presented

by the petition (371 U.S. 811; R. 285). The jurisdic

tion of this Court rests upon 28 U.S.C. 1254(1).

QUESTION PRESENTED

Whether the transfer provisions in the plans of school

desegregation approved by the courts below, which

provide for automatic transfer solely on grounds of

race out of the integrated school to which a pupil is

assigned on the basis of residence back to his former

segregated school, invalidates those plans as remedies

for the denial of petitioners’ rights under the equal

protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

INTEREST OF THE UNITED STATES

The instant cases are the first school desegregation

cases that this Court has agreed to review on plenary

3

hearing since Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1. They

present a significant question regarding the permis

sible means to effectuate school desegregation. The

question is also one about which lower federal courts

have disagreed. Compare the views of the Sixth

Circuit expressed in Kelley y. Board of Education

of City of Nashville, 270 F. 2d 209, certiorari de

nied, 361 U.S. 924, and the opinions below, with the

holdings of the Fourth and Fifth Circuits in Dillard

v. School Board of City of Charlottesville, Ya., 308

F. 2d 920, and Boson v. Hippy, 285 F. 2d 43.1

I t is now over eight years since this Court’s deci

sion in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483,

when state authorities became “duty bound to devote

every effort toward initiating desegregation and bring

ing about the elimination of racial discrimination in

the public school system.” Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S.

1, 7. As a consequence, 255,367 of the 3,279,431 Ne

groes of school age living in the southern and border

states and the District of Columbia-—representing 7.8

percent—have come to attend biracial schools.2 To

some, this represents great progress in bringing about

1 Two district courts have also refused to approve desegrega

tion plans containing transfer provisions similar to those in

volved in this case. See Mapp v. Board of Education of City

of Chattanooga, 203 F. Supp. 843 (E.D. Tenn.); Vick v.

County Board of Education of Obion County, 205 F. Supp.

436 (W.D. Tenn.).

2 243,150 of these Negroes (95.2 percent) live in Delaware,

District of Columbia, Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, Okla

homa, and West Virginia. See Statistical Summary of School

Segregation-desegregation in the Southern and Border States,

p. 3, published by the Southern Education Reporting Service

(November 1962).

4

changes in deep-rooted social patterns; to others, the

pace has been too slow. The realization of the rights

enunciated, by this Court in Brown v. Board of Edu

cation, is of extreme importance to millions of Ameri

can citizens, and the attainment of a nation-wide sys

tem of non-diseriminatory public education with the

least disturbance or other interference with public

education is of vital interest to the country as a

whole.

The United States has participated in the two pre

vious cases in this Court involving school desegregation

problems. We believe that in these cases, because of

the nature of the issue presented and the disagree

ment of the lower courts, it is again incumbent upon

the United States to express its views.

STATEMENT

These actions were initiated by Negro pupils and

their parents to desegregate the public schools in

Knoxville, Tennessee, and Davidson County, Tennes

see (an area adjacent to the City of Nashville.)3

Both suits were brought as class actions under Rule

23(a)(3), F.R. Civil P., against the local school au

thorities seeking injunctive and declaratory relief to ob

tain desegregation in accordance with Brown v. Board

of Education, 347 U.S. 483, 349 U.S. 294.4 In each case

the jurisdiction of the district court wTas invoked pursu

ant to 28 U.S.C. 1331, 1343, 2201, and 2202 and rights

3 The Goss case was filed on December 11, 1959, in the District

Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee (E. 5). The

Maxwell case was filed on September 19, 1960, in the District

Court for the Middle District of Tennessee (E. 165).

4 As early as August 17, 1955, the Knoxville School Board

recognized that it was required to take steps to implement the

5

were asserted under 42 U.-S.C. 1981 and 1983 (R. 5-6,

171-172).5 6 In both eases, the school authorities acknowl

edged by their answers that they were continuing to

operate racially segregated public school systems (R.

27, 202).6 After directions from the trial courts to

present desegregation plans (R. 29, 208), both boards

Brown decision. Various study groups were formed and

eventually eight possible plans of desegregation were presented

to the school board. At a meeting on May 11, 1956, the

school board announced that the plans had been studied but

all had been rejected because it “did not feel at that time

that desegregation of the Knoxville Public Schools could be

successfully put into operation” (it, 43-46, 122-123).

I t does not appear that the Davidson County School Board

took any steps to implement the Brown decision prior to the

institution of this suit (It. 190, 202, 204).

5 In the Maxwell case, the plaintiffs also attacked the assign

ment of school personnel on the basis of race and requested

that any desegregation plan provide for the assignment of

teachers, principals, and other school personnel on a non-racial

basis (ft. 174-175, 184).

6 The answer of the defendants in Goss said (R. 27) : “I t is

therefore stated to this Court that the said defendants do not

for one moment admit to any dereliction of duty on their, or

their predecessors’ part in not having hastened to obey the

Supreme Court’s pronouncement. Two duties of these defend

ants have sharply clashed, the one to obey the Constitution of

the United States as so recently interpreted, the second to honor

and respect an allegiance to our community and its members

which incorporates in its very fabric a careful protection of our

cherished institutions. More particularly, there is the absolute

compulsion to seek ever for efficient, undisturbed and continu

ous schooling, unmarred by the possibility of interruption from

drastic unpopular change. The defendants have simply dis

charged the responsibilities of their offices in the only way that

a proper reconciliation of conflicting allegiances has permitted.

The defendants owe no apologies to anyone, and make none.”

e

adopted plans to desegregate one school grade each

year oyer a twelve-year period beginning with the

first grade in 1960 in Knoxville and in 1961 ip David

son County (R. 30; 214). While there were differ

ences in wording, the two plans were substantially

the same. Both contained provisions for rezoning of

schools without reference to race, and for a system of

transfers.

The transfer rule, which is at issue in this ease, pro

vides that, in certain instances, pupils may obtain

transfers from the schools in their zones of residence

to other schools. The Knoxville plan, which is essen

tially the same as the Davidson County plan, provides

(R. 31-32):

6. The following will be regarded as some of

the valid conditions to support requests for

transfer:

a. When a white student would otherwise be

required to attend a school previously serving

colored students only:

b. When a colored student would otherwise

be required to attend a school previously serv

ing white students only:

c. When a student would otherwise be re

quired to attend a school where the majority of

students of that school or in his or her grade

are of a different race.

Both plans also contain general provisions stating

that transfers will be granted when “ good cause” is

shown.7

7 The Knoxville Plan provides (E. 31) :

“5. Bequests for transfer of students in desegregated grades

from the school of their Zone to another school will be given

7

Petitioners filed in the respective district courts

written objections to both plans including specific

objections to the above quoted transfer rule (R. 32-

34, 215-219).8 9 In each case the district court held a

hearing to consider the adequacy of the plan.

The Evidence and Lower Court Holdings in the

Goss Case.8—Dr. Burkhart, the president of the Knox

ville school board, testified that the transfer provision

was intended to provide for “ hardship circumstances”

(R. 85). When asked, “ * * * this feeling of the

board that there should be provision for transfers

based on race—this is attributable to the board’s feel-

full consideration and will be granted when made in writing by

parents or guardians or those acting in the position of parents,

when good cause therefor is shown and when transfer is prac

ticable, consistent with sound school administration.”

The Davidson County Plan provides (R. 214) :

“4. Application for transfer of first grade students, and sub

sequent grades according to the gradual plan, from the school of

their zone to another school will be given careful consideration

and will be granted when made in writing by parents, ghard-

ians, or those acting in the position of parents, when good cause

therefor is shown and when transfer is practicable and con

sistent with sound school administration.”

8 The objection in the Goss case was as follows (R. 34):

“Paragraph six (6) of the plan violates the due process and

equal protection clauses of the Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the United States in that said paragraph pro

vides racial factors as valid conditions to support requests for

transfer, and further in that the racial factors therein provided

are manifestly designed and necessarily operates to perpetuate

racial segregation.”

9 The record mainly relates to the adequacy of the twelve-year

plan of desegregation, but, since this matter is not here under

review, our statement of facts is limited to matters bearing on

the transfer plans.

6T130&— 63- -2

ing with regard to the hostility of the community to

this sort of change; is that it?,” he answered (R. 85) :

Not as much as to the effect that it might

have upon the students. I would like to be

clear on the matter that our primary concern

is the education of our students, all of them.

This is our prime concern.

Other factors enter into our decision, but our

primary concern is the orderly education of our

students, both white and colored, in an effort

to make available to the community the best

facilities and instructional facilities that we can

under the least possible circumstances which

might be harmful.

Dr. Burkhart explained that the board thought it

might be “harmful” to a certain number of white

students to go to school with Negroes and also “it

might be harmful to some of the colored students to

go with white students if they didn’t want to” (R. 85).

He said the basis for this feeling was (R. 86) :

The fact that we are talking about two sepa

rate races of people, with different physical

characteristics, who have not in our community

been very closely associated in many ways and

certainly not in school ways. And there would

be a sudden throwing together of these two

races which are not accustomed to that sort of

thing. Either of them might suffer from it

unless we took some steps to try to decrease

that amount of suffering or that contact which

might lead to that in case it did occur.

He stated that he did not necessarily refer to physical

harm but was more concerned with “mental harm.”

Dr. Burkhart testified that he did not know pre-

8

9

eisely what procedure would be used to notify stu

dents of their new school zones (R. 91-92), but he did

indicate how he expected the transfer plan would

operate (R. 93-94) :

Q. I am asking you do you or does the board

anticipate that any white students will remain

in schools which have been previously zoned or

used for Negroes exclusively?

A. We doubt that they will.

Q. As a matter of fact, none have remained

in the City of Nashville, have they? 10

A. I don’t know. * * *

Q. So then a Negro student who happens to

be in a zone where the school for his zone is a

school which was formerly used by Negroes

only, that school will be continued to be used

for Negroes only and he will remain in a

segregated school, will he not?

A. Yes, sir.

10 The Knoxville and Davidson County transfer provisions

were copied from the Nashville desegregation plan (R. 219).

The experience under the Nashville plan is summarized in Re

port of the United States Commission on Civil Rights, Civil

Rights U.8.A./Public Schools Southern States 1962, pp. 115-

116: “After 3 years of desegregation, only 13 percent of the

Negroes eligible to attend white schools were doing so. No

exact figures are available for the 1961-62 year, but school offi

cials estimate the percentage is appreciably higher—perhaps

20 percent. After 3 years, there were no whites in Negro zones

attending a Negro school. Last, year, there were only the two

attending the Negro Pearl Elementary School. There have

been no recent figures compiled on the number of whites orig

inally assigned to Negro schools, but when desegregation

began in 1957 there were 55, all in the first grade. Projecting

this known figure to five grades, the total number would have

been 275 in 1961-62.”

10

Q. And if lie applied for transfer out of his

zone to a school which has been formerly serv

ing white students only, then his application

would be denied under this plan, would it not,

sir?

A. Unless it were based on one of the other

reasons that we have established for transfer.

I f transferred under one of those, it would be

granted.

* * * * *

Q. But a white student to transfer out of a

Negro school, as you have stated, would be

entitled to do so, to have his application granted

as a matter of course under paragraph 6, sub-

paragraph “ a” or “c” of this plan?

A. Yes, sir.11

Mr. Marable, a school administrator in charge of

handling transfer requests, described the system used

before the plan involved in this case was adopted (R.

112). He said that transfer requests were evaluated

on a case by case basis, no specific rules were followed,

he was vested with great discretion, and generally

transfers were granted for “hardship cases and con

venience” (R. 112-117).

The district court, with one modification, approved

the Knoxville desegregation plan, but did not discuss

the transfer provisions in its memorandum opinion

11 School board member Ray also acknowledged that the

operation of the transfer provision would tend to perpetuate

segregation (R. 104). Another board member, Dr. Moffett,

stated that the transfer provisions “ [a]t least give the opportu

nity” to perpetuate segregation as they are availed of by stu

dents or parents (R. 108).

11

(R. 119).12 During the trial, the court indicated that

it regarded itself as bound by the Sixth Circuit’s prior

approval of an almost identical provision in the Nash

ville, Tennessee, school case (Kelley v. Board of

Education of Nashville, 270 F. 2d 209, 228, certiorari

denied, 361 U.S. 924) (R. 94).

After the district court’s decision, the school board

adopted a resolution providing for administration of

the transfer provision as follows: “All first grade

pupils should either enroll in the elementary school

within their new school zone or in the school which they

would have previously attended” (R. 141).13 14 This

procedure avoided assigning students to schools within

their new zones and then requiring them affirmatively

to seek a transfer if they desired to take advantage

of the transfer provisions of the plan. Rather, stu

dents were given the option to enroll in the school pre

viously attended, i.e,, the segregated school (R. 145,

151). Petitioners, claiming that this administrative

device further demonstrated that the transfer plan

would perpetuate segregation, moved for a new trial

(R. 138-155).“ The motion was denied by the district

court (R. 155).

12 The district court approved the Knoxville desegregation

plan in all respects except that it required the school board

to re-study and re-submit a plan relating to an all-white

vocational school offering technical courses not available to

Negro students.

13 As of January 22, 1960, 78 percent of the students in Knox

ville were white and 22 percent were Negro. There were 30

white schools and 10 Negro (E. 26). The record does not

indicate which of these schools were elementary schools and

which were high schools.

14 Petitioners alleged that (R. 154) : “ (b) Under the plan, as

elucidated by the procedure established in said policy, pupils

will be assigned routinely to said Negro and white schools ac

12

The court of appeals approved the transfer provi

sion (R. 162; 301 E. 2d at 168).15

The Evidence and Lower Court Holdings in the

Maxwell case.—J. E. Moss, the Superintendent of

Schools of Davidson County, testified that the effect of

the transfer provisions of the Davidson County deseg

regation plan was to permit a child or his parents ‘‘to

choose segregation outside of his zone but not to choose

integration outside of his zone” ; that the provision

was identical to that in the Nashville plan; and that as

it operated in Nashville and was intended to operate

in Davidson County, white pupils were not actually

required to go first to the Negro schools in their zones

and then seek transfers out, and no Negro pupils who

did not affirmatively seek a transfer to an integrated

school were assigned to one (R. 219-220).

cording to race, as in the past, without regard to non-racial

school zones and without regard to a transfer procedure in

which the pupil affirmatively seeks a transfer from his school

in the non-racial zone to another school, (c) Said policy mani

festly is designed to impede pupils’ free choice to attend a

school in their zone, and is designed to influence students or

parents to remain in segregated schools, in that it readopts, as a

part of defendant’s official assignment policy under and pursu

ant to the plan, defendants’ past policy of assigning pupils to

racially designated schools.”

15 The court modified the district court’s judgment “insofar as

it approved the board’s plan for continued segregation of all

grades not reached by its grade-a-year plan,” and remanded,

instructing the district court “to require the board to promptly

submit an amended and realistic plan for the acceleration of

desegregation” (R. 163-164; 301 F. 2d at 169). On June 25,

1962, the Knoxville School Board voted to double the rate of

desegration by opening two grades a year instead of one. See

Report of the United States Commission on Civil Rights,

Civil Rights U.S.A./Public Schools Southern States 1962, p. 130.

13

Another witness, Dr. Eugene Weinstein, a professor

at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, testified that

the experience in Nashville was “mass paper trans

fers of whites back into what is historically the

white school, of Negroes remaining in what is histori

cally the Negro school,” and that the transfer pro

visions tend to keep the system oriented toward a

segregated system with token desegregation (R. 226).

The district court, while modifying some aspects of

the desegregation plan submitted by the school board,

approved the transfer provisions of the plan (R.

242).16 As in the Goss case, additional proceedings

were held in the district court after petitioners moved

for further relief to object to the manner in which the

transfer provisions were being administered (R. 244).

The evidence showed that, as a result of the rezoning,

288 white children were in zones of the 7 elementary

schools that were previously all Negro and 405 Negro

children were in zones of the 62 elementary schools

that previously were all white (R. 194, 252).17 The

18 The court modified the school board’s twelve-year plan to

require that the first four grades be desegregated as of January

1, 1961, with an additional grade to be desegregated each Sep

tember thereafter until all grades were covered (R. 240-242).

The court also refused injunctive relief to several plaintiffs in

higher grades that were still segregated who sought admis

sion to white schools nearer their homes as exceptions to the

plan (K. 241-242, 269-270). With respect to petitioners’ re

quest that the school board eliminate segregated teacher and

personnel assignments, the court reserved judgment (R. 241-

242).

17 As of September 1960, 95 percent of the students in David

son County were white and 5 percent were Negroes. There

were 62 white elementary schools, 16 white high schools, 7

Negro elementary schools, and one Negro high school (R. 194).

14

school authorities sent notices to the parents of these

693 students asking them to indicate within three days

whether they requested permission for the children

to stay at the school previously attended (i.e., the

segregated school) or requested permission for a

“transfer” to the newly zoned school (R. 247-250).18

Petitioners contended that these notices were mis

leading and encouraged the continued maintenance of

racial segregation in that assignments were actually

to a segregated school from which there must be a

transfer out (R. 245). The district court held that

the notices were adequate and unobjectionable.19

18 Of this group, only fifty-one pupils, all of them Negroes,

asked to attend the school in the new zones (It. 265).

19 In its second findings of fact, conclusions of law, and

judgment the court. considered further the question of teacher

assignment on a racial basis. The court indicated that

it did not believe that this issue had been finally settled by the

Brown case but recognized that serious problems were presented

under the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment (R. 271) : “Particularly is this true when the Court con

siders the fact that a plan has been approved for Davidson

County which includes a very liberal transfer provision. When

this provision, although it is on a voluntary basis, is coupled

with a policy (and the Court is not now finding that the policy

exists in Davidson County) which would assign teachers on

the basis of race, then a serious question is presented to the

. Court as to whether there is not actually being thereby perpetu

ated the very condition which the Supreme Court said could

not be perpetuated, and this is a segregated system of public

schools * * *. The Court finds that it is not necessary to deter

mine the question relative to the assignment of school teachers

and other personnel at this time for the reason that the Court

does not believe (even if it should now hold and declare that

the plaintiffs do have the right to attend a school system

where race is not one of the factors considered in the assign

ment of teachers) that an injunction should issue at this time.”

The court stated that the plaintiffs could renew this question at

a later date (R. 272).

15

On appeal, the court of appeals approved the trans

fer provision on the authority of its decisions in the

Kelley and Goss cases (R. 284; 301 F. 2d at 829).

SBMMAEY OS' ARGUMENT

This Court held in Brown v. Board of Education,

349 U.S. 294, 301, that racial desegregation of the

public schools must proceed “with all deliberate speed.”

Compliance with this obligation requires the elimina

tion of segregation as soon as possible. We recognize

that school segregation is often merely one part of a

deep-seated pattern of racial discrimination which,

while contrary to national policy, currently enters

into the make-up of many children, both white and

colored. Any interim plan for desegregation can

properly take account of educational problems.

Therefore, while mere hostility to desegregation is not

a relevant factor, a district court or school board is

not required, given present conditions, to omit suit

able provisions for meeting any problems of adjust

ment affecting the educational development of indi

vidual pupils.

The transfer plans in these cases, however, cannot

be justified as an essential part of sound school admin

istration. They are not adapted simply to promoting

the educational welfare of individual children.

A. The transfer plans were based solely on race and

therefore plainly are inconsistent with the Fourteenth

Amendment. Negro children living in areas where the

671303—6: 3

16

school was formerly all-Negro and presently has a

majority of Negroes are not permitted to transfer

whereas white children having a residence in the same

area can transfer. The only basis for the different

treatment is the difference in race.

I t is irrelevant that white children in a residential

zone where the school was formerly all-white and

which presently has a majority of white students can

not transfer whereas Negro students in this same zone

can transfer. Superficial equality of treatment was

rejected in Brown v. Board of Education, which

held that a separate-but-equal public school system

was unconstitutional. Moreover, the right to nondis-

criminatory treatment is a personal right; the right of

some Negro children to be treated the same as white

children in the same circumstances cannot be denied

on the ground that other Negro students have rights

denied to white students.

B. The transfer plans tend to preserve segregation.

They allow any pupil to transfer from a school which

formerly served only the other race, or from a school

which is presently composed of a majority of the

other race. This means that students are free to re

turn to their old racial environment but not to trans

fer to a new racial environment. Thus, the transfer

provisions invite immediate and continuous resegre

gation solely upon the basis of race. This was the

intent of the proponents, and the intent is confirmed

by their actual operation.

17

C. Just as the burden is on the school board to jus

tify delay in according Negro children their constitu

tional rights (Brown v. Board of Education, supra),

so does a school board have a heavy burden to justify

provisions in the desegregation plan which reintro

duce racial classifications and appear to support re-

segregation. At the least, the school board must dem

onstrate convincingly that the provisions are necessary

to meet educational problems.

Here, no such evidence exists. No proof was even

offered that the transfer provisions were needed to

effect an orderly transition. The only possible legiti

mate objective they could have had was to alleviate

any educational problems individual students might

have in adjusting to a school where the overwhelming

majority of students were of a different race. But

the provisions under review were badly designed to

meet this purpose. They would allow students to

transfer even when the school was racially balanced,

or even when a majority of students were of their

own race if the school formerly served a different

race.

More important, there are practical alternatives—

which are not based on racial criteria and do not

support segregation—for meeting any legitimate edu

cational problems in requiring students to at

tend a school predominantly composed of students

of a different race. For example, a school board

could allow any student who desired to transfer to

18

do so, thereby allowing all students the opportunity to

attend desegregated schools, instead of merely those

living in particular areas. This plan has been fol

lowed in large cities with substantial Negro popula

tions, such as Louisville and Baltimore. The school

board could also attempt to eliminate the problem of

a small minority of students of one race in a school

largely composed of another by drawing residential

zones in order to introduce a greater balance. Or the

school board could apply transfer provisions based on

educational and psychological criteria which would

apply to children on an individual basis. Such pro

visions, which are not based on race, have been upheld

by the lower courts.

ARGUMENT

We read the plans of the school boards in these

cases and also the decrees below as directed to the

existing situations in Knoxville and Davidson

County—to a period of transition from racially seg

regated schools to a school system fully complying

with the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. In each case the district court retained

jurisdiction of the action “ during the period of transi

tion” (R. 138, 242). The court of appeals specifically

noted, with respect to the transfer plan, that (R.

162) :

Hie trial judge retains jurisdiction during the

transition period and the supervision of this

phase of the reorganization may be safely left

in his hands.

19

No transfer plan explicitly based upon race is per

manently acceptable under a Constitution that

prohibits state action in which race or color is the

determinant. See infra, pp. 22-28. The critical issue

in this case, however, as we read the decrees below, is

whether the Knoxville and Davidson County transfer

plans may be put into effect today, during a period of

transition, consistently with this Court’s ruling that

school districts shall proceed to full integration “ with

all deliberate speed.” Brown v. Board of Education,

349 U.S. 294, 301.

Compliance with this obligation in a manner that

takes into account “ the public interest in the elimina

tion of * * * obstacles in a systematic and effective

manner” (id. at 300) calls for the accommodation of

two prime objectives. First, the plan must move

ahead towards complete compliance with the Four

teenth Amendment’s requirement of “ a racially non-

diseriminatory school system.” Id. at 301. Although

Brown and Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, involved ad

mission to school and the opinions speak chiefly in

those terms, it is too plain for argument that the equal

protection clause prohibits the administration of any

aspect of public education upon the basis of race, and

therefore the elimination of any such discrimination

is an essential aim of everj ̂decree.

Second, since the welfare of the children is the cen

tral purpose of all public school education, any in

terim plan must take into account their individual

intellectual and psychological development affecting

education. In many communities school segregation

has been merely one part of a deep-seated social pat-

20

tern, originating in slavery and continuing through

racial segregation and discrimination. The evil must

be eliminated. The current existence and deep roots

of the social pattern are nevertheless temporary facts

which have left their effect upon many children, both

white and colored. Neither hostility to desegregation

nor disapproval of basic constitutional principles is a

relevant factor in formulating a plan or determining

the speed of transition (Brown v. Board of Educa

tion, 349 U.S. 294, 300; Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1,

7), but, given the present facts, a district court or

local school board is not required to omit from its

plan of transition suitable provisions for avoiding

educational damage to individual pupils as a result of

too sudden a forced reversal of rooted habits.20

The transfer plans approved by the courts below

were ostensibly designed to meet these objectives of

wise school administration. See the Statement, supra,

p. 8. We have no quarrel with that purpose.

Given existing conditions, requiring a particular white

child who had always lived a sheltered life in a rigidly

segregated community suddenly to go to an over

whelmingly Negro school might create problems of ad

justment interfering with the individual’s educational

development. Conversely, forcing a Negro child to

break away from his established pattern and at

tend an all-white school might in some circumstances

impair his development. In our view, the constitu

tional obligation to desegregate the schools “with all

deliberate speed” does not require blindly forcing

20 Under these circumstances, the school board has an initial

obligation to prepare students for desegregation so as to lessen

the educational and psychological problems.

21

white children now to attend overwhelmingly Negro

schools or Negro children now to attend over

whelmingly white schools at the sacrifice of their

individual welfare. School authorities may properly

take such problems of individual adjustment into

account along with the equally important problem of

avoiding psychological or educational damage to

Negro children as a result of forcing them to attend

all-Negro schools.

Despite its announced objective the transfer plan

involved in these cases fails to satisfy the require

ments laid down in Brown v. Board of Education,

supra. In our view the plan has three interrelated

defects:

1. I t introduces into the administration of public

education in Knoxville and Davidson County a plan

of transfers based solely and explicitly upon race,

rather than individual welfare.

2. I t tends to preserve the old system of segregated

schools by authorizing, upon explicit racial grounds,

automatic self-assignment to the school attended un

der segregation.

3. I t ignores the availability of other tested meth

ods of securing the educational welfare of children

related to problems of adjustment, which are con

sistent with the Constitution.

Whatever might be the consequence of any one of

these defects standing alone, taken together and in a

context of extreme dilatoriness in proceeding to de

segregation, they vitiate the Knoxville and Davidson

County plans for redressing the violations of peti

tioners’ constitutional rights. In the remainder of

this brief we shall discuss these three objections.

22

A. THE PLAN OF PUPIL TRANSFERS BASED SOLELY UPON

RACE VIOLATES THE EQUAL PROTECTION CLAUSE OF THE

FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT

Classifications based on race have been repeatedly

held by this Court and by the lower federal courts to

violate the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment. Perhaps the most famous enunciation

of the principle was by Mr. Justice Harlan, dissenting

in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537, 554, 559:

[T]he Constitution of the United States does

not * * * permit any public authority to know

the race of those entitled to be protected in the

enjoyment of * * * [civil] rights.

* * * * *

Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither

knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.

* * * The law regards man as man, and takes

no account of his surroundings or of his color

when his civil rights as guaranteed by the

supreme law of the land are involved.

More recently, this Court has stated that, racial

classifications are “ obviously irrelevant and in

vidious.” Steele v. Louisville & Nashville Rail

road Go., 323 U.S. 192, 203. Nor is the constitutional

right to equality limited to any class of situations or

category of state action. The Fourteenth Amend

ment prohibits any “ state action in which color (i.e.,

race) is the determinant * * *. The factor of race

is irrelevant from a constitutional viewpoint.” Bald

win v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750, 754 (C.A. 5). Con

sequently, this Court has held unconstitutional a

variety of racial classifications involving, for example,

juries (Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U.S. 303;

23

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587), public education

{Brown v. Board of Education, supra), parks {New

Orleans City Park Improvement Assoc, v. Detiege, 358

U.S. 54; Dawson v. Mayor and City Council of Balti

more, 220 F. 2d 386 (C.A. 4), affirmed, 350 U. S. 877),

and restaurants in publicly owned buildings {Burton

v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715).

The use of race as the criterion for transferring pu

pils is no less unconstitutional than the use of that

distinction in their admission to school.

Both the Knoxville and Davidson County plans

make race a sole and explicit criterion for transfer

ring a student from one school to another. Para

graph 6 of the Knoxville plan provides that a transfer

will be automatically approved—

a. When a white student would otherwise be

required to attend a school previously serving

colored students only;

b. When a colored student would otherwise

be required to attend a school serving white

students only;

c. When a student would otherwise be re

quired to attend a school where the majority

of students of that school or in his or her grade

are of a different race.

No words could make it clearer that the test is one of

color.

The superficial equality which the plan accords

white and Negro children by enabling each race to

leave an integrated school does not save it from in

validity. A similar argument was made in defense of

the separate-but-equal public schools existing prior to

Brown v. Board of Education. Under that system

white children were required to go to school only with

other white children just as Negro children could only

go to school with Negroes. Nevertheless, this Court

held that this racial classification violated the rights

of Negro children.

Moreover, the right to non-discriminatory treat

ment is a personal right. See Brown v. Board of

Education, supra, 349 U.S. at 300 (“ [a]t stake is a

personal interest of the plaintiffs in admission to pub

lic schools as soon as practicable on a nondiscrimina-

tory basis”); Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629, 634;

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U.S. 631, 633. Thus,

in Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1, it was argued that

a restrictive covenant based on race could validly be

enforced against Negroes by a state court since the

court would also enforce similar covenants against

white persons. This Court, however, rejected the con

tention (id. at 22) :

The rights created by the first section of the

Fourteenth Amendment are, by its terms, guar

anteed to the individual. The rights established

are personal rights. I t is, therefore, no answer

to these petitions to say that the courts may

also be induced to deny white persons rights of

ownership and occupancy on grounds of race or

color. Equal protection of the laws is not

achieved through indiscriminate imposition of

inequalities.

The extent to which the transfer plan makes race

the criterion is emphasized by the fact that it operates

solely in the direction of resegregation. White stu

dents may transfer out of any school which formerly

served Negroes. Negroes may leave any school which

formerly served whites. But no Negro has the same

25

automatic privilege to leave a school that served Ne

groes in order to attend integrated classes.

The omission underscores the purely racial char

acter of the differentiation. White students living in

a residential zone where the school was formerly all-

Negro and is still attended by Negro students have the

right to transfer, but Negro students who live in the

same area are not allowed to transfer, even though

they might equally benefit from the change. Obvi

ously the personal constitutional rights of these Negro

students are denied by the racial classification.

The foregoing aspect of these transfer plans em

phasizes wrhat is already apparent on their face—

that the criterion is not the equal welfare of all chil

dren without regard to race; it is race, and race alone.

In emphasizing this point we fully recognize that in

some communities, during the transitional period,

measures for accomplishing desegregation may create

individual educational problems, and that it is wise

school administration to take such transitional prob

lems of personal adjustment into account even when

they originate in customs fixed by race. An interim

plan adapted to this purpose, if sincerely aimed

at abolishing racial discrimination in the schools,

would provide means for not only alleviating problems

of individual children who would suffer from difficulty

in adjusting to a school where they were numerically

overwhelmed by a different race, but also for meet

ing the problems of Negro children who would other

wise suffer from a segregated education because they

happened to live nearest a school in an overwhelmingly

Negro part of the community. Such a plan, more

over, would be framed in terms of the welfare of indi

vidual children and would take some account of cir

cumstances other than race or color. The problems

of adjustment of a nervous boy or girl, who has lived

in a segregated community, when forced to attend a

school where all the other pupils are of a different

race, are very different from those of children in a

school where the minority is much larger, and still

different, no doubt, from those where the proportions

are fairly equal.

I t may be argued that in the early stages of transi

tion administrative convenience requires a rule of

thumb because the difficulties of investigating the

situation of each child would be overwhelming. We

do not agree that mere administrative convenience

is a sufficient justification for making a classification

according to race. In other contexts such problems

may justify rough working distinctions, but the equal

protection clause is more exacting when a State deals

with fundamental personal rights. Cf. Skinner v.

Oklahoma, 316 U.S. 535. In any event the record

contains no evidence to support such a claim; and it is

belied by the numerous pupil assignment laws upheld

by the lower courts. Those laws which have been

sustained make no mention whatsoever of race as a

basis for transfer. E.g., Shuttlesworth v. Birming

ham Board of Education, 162 F. Supp. 372 (NJD.

Ala.), affirmed on limited grounds, 358 U.S. 101;

Parham v. Dove, 271 F. 2d 132 (C.A. 8) ; Carson v.

Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724 (C.A. 4). When race, as such,

has been found to be a consideration affecting trans

,20

fers, the appellate courts have uniformly held the

statutes to be applied invalidly. See, e.g., Norwood

v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798 (C.A. 8) ; Mannings v. Board

of Public Instruction, 277 F. 2d 370 (C.A. 5) ; Green

v. School Board of the City of Roanoke, Virginia,

304 F. 2d 118 (C.A. 4); Marsh v. County School

Board of Roanoke, Virginia, 305 F. 2d 94 (C.A. 4) ;

Jones y. School Board of City of Alexandria, 278 F.

2d 72 (C.A. 4). Furthermore, other communities

have developed entirely workable programs that meet

pupils’ needs without introducing invidious distinc

tions based solely upon race. See infra, pp. 36-40.

B.. THE PLAN UNLAWFULLY TENDS TO PRESERVE SCHOOL

SEGREGATION BY AUTHORIZING AUTOMATIC SELF-AS

SIGNMENT, UPON EXPLICIT RACIAL GROUNDS, TO THE

SCHOOL ATTENDED UNDER SEGREGATION

A prerequisite of every acceptable plan of school

desegregation is that it move definitely and expedi

tiously away from the old regime of racial discrimi

nation. There is room for dealing with all genuine

problems of school administration and pupil welfare.

There is no room for nominal compliance followed

by racial resegregation even though this be the wish

of the local community. In Brown v. Board of Edu

cation, 349 U.S. 294, 300-301, the Court said:

* * * the courts will require that the defend

ants make a prompt and reasonable start toward

full compliance with our May 17, 1954, ruling.

Once such a start has been made, the courts

may find that additional time is necessary to

carry out the ruling in an effective manner.

27

28

The burden rests upon the defendants to es

tablish that such time is necessary in the public

interest and is consistent with good faith com

pliance at the earliest practicable date. To that

end, the courts may consider problems related to

administration, arising from the physical con

dition of the school plant, the school trans

portation system, personnel, revision of school

districts and attendance areas into compact

units to achieve a system of determining ad

mission to the public schools on a nonracial

basis, and revision of local laws and regulations

which may be necessary in solving the fore

going problems. They will also consider the

adequacy of any plans the defendants may

propose to meet these problems and to effectu

ate a transition to a racially nondiscriminatory

school system.

In Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 7, the Court elabo

rated the meaning of the Brown decisions:

Of course, in many locations, obedience to the

duty of desegregation would require the im

mediate general admission of Negro children,

otherwise qualified as students for their ap

propriate classes, at particular schools. On

the other hand, a District Court, after analysis

of the relevant factors (which, of course, ex

cludes hostility to racial desegregation), might

conclude that justification existed for not re

quiring the present nonsegregated admission of

all qualified Negro children. In such circum

stances, however, the courts should scrutinize

the program of the school authorities to make

sure that they had developed arrangements

pointed toward the earliest practicable com

29

pletion of desegregation, and had taken ap

propriate steps to put their program into effec

tive operation. I t was made plain that delay

in any guise in order to deny the constitutional

rights of Negro children could not he counte

nanced, and that only a prompt start, diligently

and earnestly pursued, to eliminate racial segre

gation from the public schools could constitute

good faith compliance. State authorities were

thus duty bound to devote every effort toward

initiating desegregation and bringing about the

elimination of racial discrimination in the

public school system.

The school plans involved in these cases are in di

rect opposition to the Court’s directions. Although

they provide for substituting pupil assignments based

upon zoning in place of racial segregation at the rate

of a grade each year, they invite immediate and con

tinuous resegregation solely upon the basis of race.

Any white pupil may automatically transfer out of a

school that formerly served Negroes, just because he

is white. Any Negro may automatically transfer out

of a school that formerly served white pupils, just

because he is a Negro. These transfer provisions

emphasize preservation of past unconstitutional pat

terns. The test is racial. The reference is to the

character of the school under the prior unconstitu

tional pattern of racial segregation. The transfers

operate only to preserve the past. A pupil may

transfer out of a new school at which he will find

students of both races, presumably to return to his old

racial environment, but no one may transfer from his

old school to a new racial environment. The transfers

30

can work only in the direction of segregation. A

student who is assigned under the new zoning to an

integrated school where most of the pupils happen

to be of a different race may transfer out of the area

to another school where conditions more nearly ap

proach the old pattern of segregation. On the other

hand, a Negro student who is assigned to a school

that happens to be all-Negro has no right to transfer

to a school attended by pupils of both races.

The extent to which these transfer plans preserve

the past unconstitutional pattern is emphasized by the

initial steps in their administration. The Knoxville

school board adopting a resolution providing for the

administration of the transfer provisions as follows

(R . 139):

All first grade pupils should either enroll in

the elementary school within their new school

zone or in the school which they would have

previously attended. [Emphasis added.]

In other words, students were not even assigned to

schools within the new residential zones and then per

mitted to apply for transfers if they were eligible to

do so under the plan. Rather, they were from the

very outset given the option to enroll in the school

previously attended, i.e., the segregated school. In

Davidson County the school authorities sent notices

to the parents of children who, as a result of rezoning,

would be required to attend a school different from

the one they were then attending. The parents were

asked to indicate, within three days, whether they

requested permission for the children to stay at the

school previously attended {i.e., the segregated school)

31

or requested permission for a “transfer” to the newly

zoned school. Again, this permitted students to re

main where they were rather than first being assigned

to a newly zoned school and then requesting permis

sion to transfer. Instead of focusing on the future

and on arrangements for desegregated schools, these

transfer plans look backward to the period when the

schools were operated on an unconstitutional basis.

I t is clear that the proponents of the transfer pro

visions anticipated that they will operate so as to pre

serve segregation. Thus, Dr. Burkhart, president of

the Knoxville school board, testified (R. 93-94) :

Q. I am asking you do you or does the board

anticipate that any white students will remain

in schools which have been previously zoned or

used for Negroes exclusively?

A. We doubt that they will.

* ■£ * * *

Q. So then a Negro student who happens to

be in a zone where the school for his zone is a

school which was formerly used by Negroes

only, that school will be continued to be used

for Negroes only and he will remain in a segre

gated school, will he not?

A. Yes, sir.

Q. And if he applied for transfer out of his

zone to a school which has been formerly serv

ing white students only, then his application

would be denied under this plan, would it not,

sir?

A. Unless it were based on one of the other

reasons that we have established for transfer.

I f transferred under one of those, it would be

granted.

.* * * * *

32

Q. But a white student to transfer out of a

Negro school, as you have stated, would be

entitled to do so, to have his application granted

as a matter of course under paragraph 6, sub-

paragraph “a ” or “c” of the plan?

A. Yes, sir.

Finally, the actual effect of the transfer provisions

in this case shows how completely inconsistent they

are with this Court’s direction that school systems pro

ceed to operate “on a racially nondiscriminatory basis

with all deliberate speed.” In Knoxville, pursuant to

the grade-a-year plan that was approved by the dis

trict court, the first grade was desegregated in the

fall of 1960. Eighty-five Negroes were eligible to en

ter previously white schools and 300 white students

were eligible to enter previously all-Negro schools.21

Twenty-nine Negro students actually entered nine of

the “white schools” while all of the 300 eligible white

students applied for and were granted transfers.22

Desegregation in Davidson County presents a simi

lar picture. There, in January 1961, as a result of

the rezoning required by the desegregation plan, 288

white children in the first through fourth grades were

in zones of the 7 elementary schools that previously

were all Negro (R. 194, 252). Taking advantage of

the transfer provisions, all 288 students requested and

were granted permission to remain in the all-white

21 See supra, p. 11, note 13.

22 See 1961 Report of the United States Commission on Civil

Rights, Education, p. 52; Report of the United States Commis

sion on Civil Rights, Civil Rights U.S.A./Public Schools South

ern States 1962, p. 130. At the beginning of the second year of

desegregation, a total of 51 Negroes in the first and second

grades elected to attend the “white school” in their residential

zone, again in nine schools.

33

schools that they had previously attended. Similarly,

405 Negro children were in areas that were served by

the 62 elementary schools that previously were all

white. Only 51 of these students elected to remain in

these schools—thus “ desegregating” them—while the

remainder transferred to the Negro schools they had

previously attended (R. 265).

In sum, the transfer provisions of the Knoxville and

Davidson County school plans, by permitting automatic

transfers back to the old segregated schools avowedly

on grounds of race, vitiate the plans as programs of

desegregation. For taken as a whole neither plan can

fairly be viewed as a bona fide effort to eliminate

racial considerations from the school system, tem

porarily tempered by the realization that previous

social patterns may have to be taken into account

in promoting the educational and psychological

welfare of individual children. Instead, the plan

says to the community, “ The School Board will do

everything possible by transfers to preserve the old

pattern of segregated schooling save only in those in

stances in which geographical zoning enables a Negro

to attend, if he wishes, an integrated school.” More

is required by the obligation to proceed “with all

deliberate speed. ’ ’

In this connection it is relevant to note the grudging

and belated compliance in both Knoxville and David

son County. See the Statement, supra, pp. 4-5, note 4.

Thus, in the Goss case the court of appeals, in disap

proving the grade-a-year plan as too slow, said (R.

161-162) :

I t has been nearly eight years since the first

Brown decision and under the plan before us

the first and second grades are now integrated.

The evidence does not indicate that the board

is confronted with the type of administrative

problems contemplated by the Supreme Court

in the second Brown decision. That the opera

tion of schools on a racially segregated basis is

a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment and

that the constitutional and statutory require

ment of the state of Tennessee prohibiting the

mixture of races in schools cannot be enforced

are no longer debatable or litigable questions.

This has been obvious and evident since May,

1954.

The position of the board that it would con

tinue to operate under these unenforeible laws,

until compelled by law to do otherwise, does

not commend itself to the Court, for the ac

ceptance of a plan that provides for a minimum

degree of desegregation. In the second Brown

case, the Court said, at p. 300: “ The burden

rests upon the defendants to establish that such

time is necessary in the public interest and is

consistent with good faith compliance at the

earliest practicable date. ’ ’ In our judgment the

defendants have not sustained this burden. We.

do not think that the twelve-year plan of

desegregation adopted at this late date meets

either the spirit or specific requirements of

the decisions of the Supreme Court.

C. OTHER TESTED METHODS ARE AVAILABLE FOR SECURING

THE EDUCATIONAL AND PSYCHOLOGICAL WELFARE

OF CHILDREN DURING A PERIOD OF TRANSITION TO

FULLY INTEGRATED SCHOOLS

Just as the burden is on a school board to justify

delay in according Negro children their constitutional

rights (Brown v. Board of Education, supra; Cooper

v. Aaron, supra), so does a school board have a heavy

34

85

burden to justify provisions in the desegregation plan

which reintroduce racial classifications and appear

to support resegregation. At the least, the school

board must demonstrate convincingly that the provi

sions will advance desegregation because they are

the best way to meet serious educational problems,

whether administrative or psychological, which would

otherwise cause hardship or delay.

The record in this case does not indicate any edu

cational problem, administrative or psychological,

which the transfer provisions are intended to solve.

No attempt was made to show that this type of provi

sion is essential to attain an orderly transition to a

nonsegregated school system. No proof was offered

to demonstrate that whatever beneficial purposes the

provision seeks to attain could not be achieved by

some other means. So far as appears, the transfer

provisions were intended merely to slow the process

of desegregation. This objective, of course, is im

permissible under this Court’s decisions in Brown v.

Board of Education, supra, and Cooper v. Aaron,

supra,.

The only legitimate objective which the transfer

provisions could be supposed to advance is to promote

the educational welfare of students by authorizing

allowance for individual problems of adjustment,

affecting a student’s educational progress, which

might result from requiring a few pupils to go

to a school where the overwhelming majority of stu

dents are of a different race. The provisions under

review, as we have seen (pp. 22-27), were badly de

signed to meet this purpose. They are phrased in

terms of race, not individual welfare. Even in those

36

terms, which would seem categorically objectionable,

one could easily write rules more adapted to the

legitimate need. The first two provisions allow stu

dents to transfer from the school in their residential

zone if the school formerly served only students of a

different race, whether or not the majority of students

in the school are now of a different race. The last

provision allows any student to transfer from a school

in which he is a member of a minority race even where

49 percent of the students are of his race.) I f the

transfer provisions were really intended to protect

students who are in a small racial minority—the only

situation where serious educational or psychological

problems seem likely—this could have been done more

appropriately by allowing, for example, a student to

transfer when only a small percent of the students

were of his race. Such a provision, while we believe it

invalid in these circumstances, would at least avoid

the resegregation of a school which had a close

racial balance by the withdrawal of all or most stu

dents of the race which was in a slight minority.

Even more important, there are practical alterna

tives—which are not based on racial criteria and which

do not support segregation—for meeting any legiti

mate educational problems of the children affected.25 23 *

23 At the least, these alternatives appear to be practical and

there is no indication in this record that they would not be

so either in Knoxville or Davidson County. Since, as we have

contended (pp. 34-35), the school boards had the burden of

showing that the transfer plans were absolutely necessary to

encourage desegregation, we must assume in the present posture

of these cases that the alternatives would prove as practical

in Knoxville and Davidson County as in the other places they

have been tried.

37

First, the school board, might allow any child who so

desired to transfer to any school which had available

space. This would mean that no child would be re

quired to attend a school overwhelmingly composed

of students of another race. On the other hand, all

students would have the opportunity to attend schools

which were desegregated—not just the few students

who happened to be in mixed residential zones. Thus,

the open transfer system would make no distinctions

in terms of race, give full freedom of choice, and

thereby encourage the desegregation of all the schools

in the jurisdiction. And the practicability of this

plan is demonstrated by its use in numerous big cities

with large Negro populations, such as Louisville and

Baltimore.24

Second, a modification of the open transfer plan is

suggested by the opinion of the Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit in Bush v. Orleans Parish

School Board, 308 F. 2d 491. There, the Orleans

Parish School Board had requested the right to trans

fer children according to the provisions of the Louisi

ana pupil placement law. The court allowed the use

34 In Louisville, the plan provides for redistricting without

regard to race. Parents are advised that they can request

transfers to schools outside of the district to which their chil

dren are assigned, and they axe asked to list three prefer

ences as to schools. Transfers are granted on the basis of

available space, convenience for the child, and individual

preferences. I t is reported that 90 percent of the parents

requesting transfers have received their first choice. Wey and

Corey, Action Patterns In School Desegregation, pp. 97-98. In

Baltimore, there are no geographic school districts. A child

may transfer from the school he is then attending. to any

school in the city, with the approval of the principals in

volved. Id. at pp. 99, 148.

38

of the placement act, but went further than merely

ordering the authorities to use it non-discriminatorily.

Because of past incidents of total withdrawal of white

children from schools which were ordered desegre

gated, the court gave the Negro children the right to

follow migrating white pupils. The order read (id.

at 502) :

Negro children who attended formerly all-white

schools in 1960-61 and 1961-62 and Negro

children who have registered for attendance at

formerly all-white schools in 1962-63 and sub

sequent years may not be transferred or as

signed to an all-Negro school against their

wishes. If the transfer of white students from

such schools would result in resegregation, the

Negro children shall be afforded an opportunity

to attend a nearby formerly all-white school

without being subjected to tests for transfer un

der the Pupil Placement Act.25 25

25 See also McCoy v. Greensboro City Board of Education,

179 F. Supp. 745 (M.D. N.C.), reversed, 283 F. 2d 667 (C.A.

4). There the Negro plaintiffs applied for admission to a

white school. The school board agreed to admit Negroes to

the school but at the same time granted transfers to the white

children and teachers. The district court dismissed the com

plaint on the ground that plaintiffs had been admitted to the

school of their choice. The court of appeals reversed and re

manded the decision with instructions that the district court

retain jurisdiction “so that the Board may reassign the minor

plaintiffs to an appropriate school in accordance with their

constitutional rights and so that the plaintiffs, if these rights

are improperly denied, may apply to the court, for further

relief in the pending action.” 283 F. 2d at 670. The court

condemned the board’s action on the ground that “although

the colored children gained admission to a superior building,

their desire to attend an integrated school was completely

frustrated.” Id. at 669.

39

Third, the desegregation plan of the school board

might entirely or substantially eliminate the problem

of a small minority of students of one race in a school

largely composed of another by drawing the resi

dential zones in a way which achieved a better balance

in some or all schools. Any educational problems for

the few students of the other race left in the zone of a

virtually all-white or all-Negro school could then be

solved on an individual basis. Were such measures

adopted even the temporary transfer provisions here

involved would be comparatively unobjectionable, for

this method produces meaningful desegregation of the

schools, in full compliance with the Fourteenth

Amendment, instead of the merely technical desegre

gation which results from allowing a few Negroes to

attend formerly all-white schools.

Fourth, where two schools exist, one formerly

Negro and one white, relatively close to one another,

the school board may assign all children, both Negro

and white, formerly attending the lower grades in both

schools (for example, kindergarten to third grade)

to one school and all the children formerly attending

the upper grades to another. The result is again to

further the process of desegregation and, at the same

time, to avoid assigning a small minority of children

of one race to a school largely composed of children

of another. This method, called the “Princeton Plan”,

after the city in New Jersey where it was employed,

has also been used in numerous other communities in

New Jersey and in Benton Harbor, Michigan, Willow

Grove, Pennsylvania, and elsewhere. See Greenberg,

Race Relations and American Law, p. 248.

40

Fifth, any educational problems, psychological or

otherwise, resulting from requiring children of one

race to attend a school largely composed of children

of another race may be handled by a transfer provi

sion not based on racial criteria. For example, in

Dallas, Texas, initial assignments are made to neigh

borhood schools and transfers are then granted on an

individual basis using the criteria of the state pupil-

placement law, which specifically forbids the consid

eration of race as a factor warranting transfer. See

Boson v. Rippy, 285 F. 2d 43, 47 (C.A. 5). The valid

ity of such a non-racial transfer provision is demon

strated by the cases upholding pupil placement laws

whenever they were administered without relation to

race (see supra, pp. 26-27).

A community is not only entitled to allow, but

should encourage, pupils to transfer when the change

will be of educational benefit. We see no reason why