A U.S. federal court today ordered the Harford County of Board Education…

Press Release

May 25, 1960

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Loose Pages. A U.S. federal court today ordered the Harford County of Board Education…, 1960. d4203a99-bc92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/56351b76-55c1-41d5-b389-cd9aa558a4d0/a-us-federal-court-today-ordered-the-harford-county-of-board-education. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

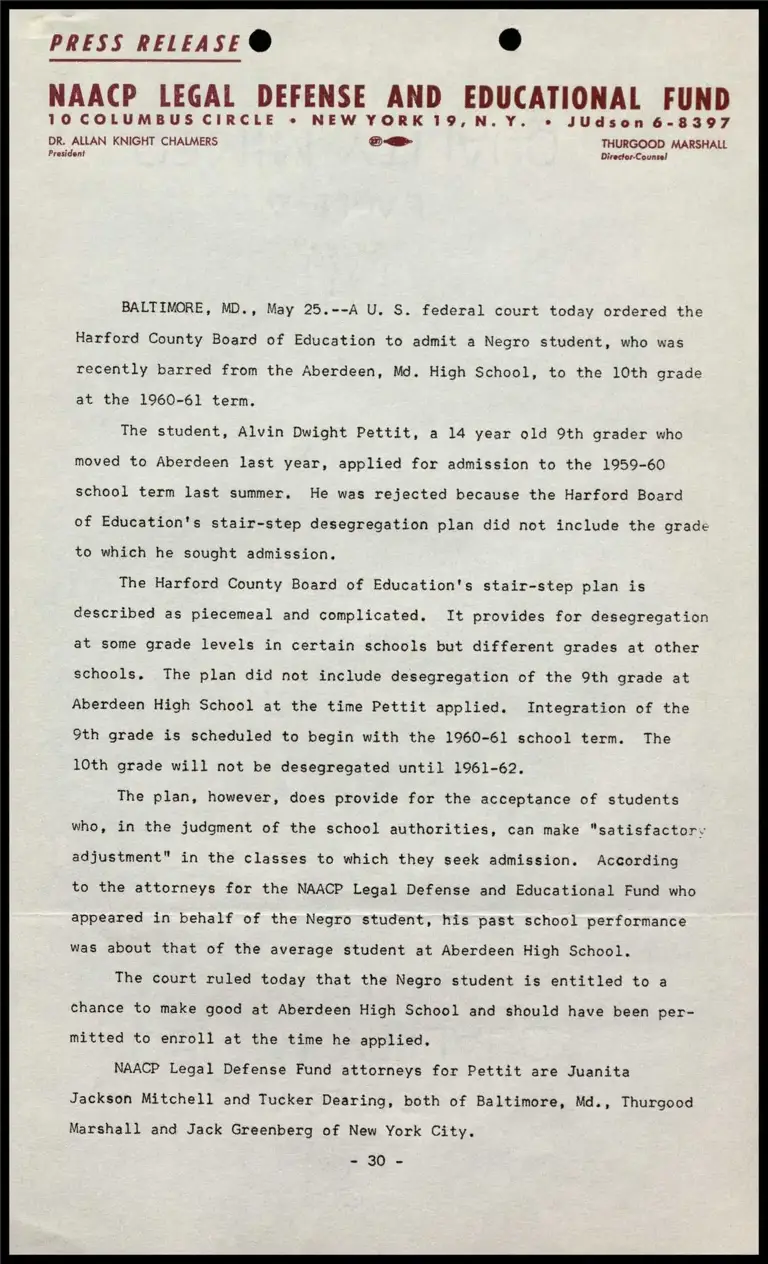

PRESS RELEASE ® @

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

10 COLUMBUS CIRCLE «© NEW YORK 19,N.Y. © JUdson 6-8397

DR. ALLAN KNIGHT CHALMERS oa THURGOOD MARSHALL

President Director-Counsel

BALTIMORE, MD., May 25.--A U. S. federal court today ordered the

Harford County Board of Education to admit a Negro student, who was

recently barred from the Aberdeen, Md. High School, to the 10th grade

at the 1960-61 term.

The student, Alvin Dwight Pettit, a 14 year old 9th grader who

moved to Aberdeen last year, applied for admission to the 1959-60

school term last summer. He was rejected because the Harford Board

of Education's stair-step desegregation plan did not include the grade

to which he sought admission.

The Harford County Board of Education's stair-step plan is

described as piecemeal and complicated. It provides for desegregation

at some grade levels in certain schools but different grades at other

schools, The plan did not include desegregation of the 9th grade at

Aberdeen High School at the time Pettit applied. Integration of the

9th grade is scheduled to begin with the 1960-61 school term. The

10th grade will not be desegregated until 1961-62.

The plan, however, does provide for the acceptance of students

who, in the judgment of the school authorities, can make "satisfactory

adjustment" in the classes to which they seek admission. According

to the attorneys for the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund who

appeared in behalf of the Negro student, his past school performance

was about that of the average student at Aberdeen High School.

The court ruled today that the Negro student is entitled to a

chance to make good at Aberdeen High School and should have been per-

mitted to enroll at the time he applied,

NAACP Legal Defense Fund attorneys for Pettit are Juanita

Jackson Mitchell and Tucker Dearing, both of Baltimore, Md., Thurgood

Marshall and Jack Greenberg of New York City.

21 90-—