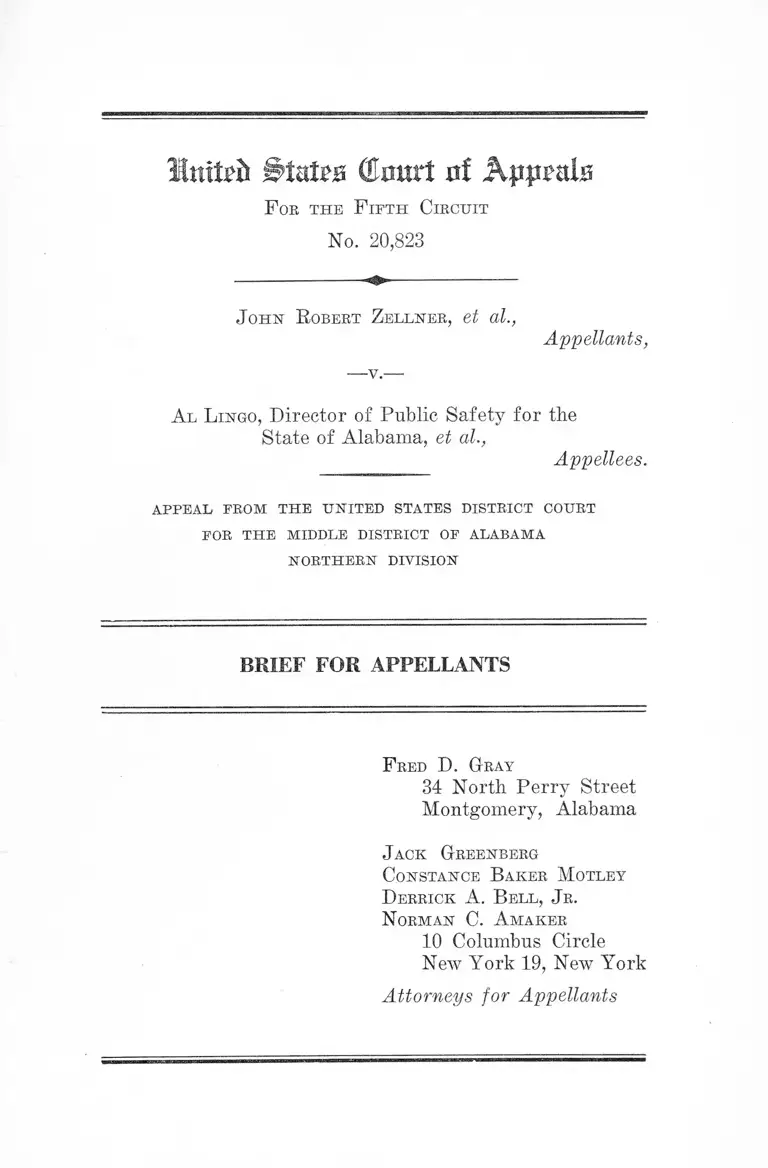

Zellner v. Lingo Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Zellner v. Lingo Brief for Appellants, 1963. a70a19ce-c99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/5637f23e-7538-402a-8ba4-ca66eca4fc31/zellner-v-lingo-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

Imteii # ta ta (Eaurf of Appeals

F or t h e F if t h C ir c u it

No. 20,823

J o h n R o b e r t Z e l l n e r , et al.,

Appellants,

-v.-

Al L in g o , Director of Public Safety for the

State of Alabama, et at,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

NORTHERN DIVISION

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

F red D . G ray

34 North Perry Street

Montgomery, Alabama

J a c k G reen berg

C o n stan ce B a k e r M o tle y

D e r r ic k A. B e l l , J r .

N o r m a n C. A m a k e r

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Appellants

INDEX TO BRIEF

PAGE

Statement of the Case .................................................... 1

Specification of Error ............ ....................................... 5

A r g u m e n t

The Court Below Erred in Dismissing Appellants’

Complaint, Because Appellants Established a Fed

eral Cause of Action in Equity .............................. 5

C o n c l u s io n ...................................................................... 17

T ab le oe C ases

Anderson v. City of Albany (5th Cir., July 26, 1963) 12

Bailey v. Patterson, 199 F. Supp. 595 (S. D. Miss.

1961), rev’d 369 U. S. 31 ........ ................................... 8,12

Baldwin v. Morgan, 251 F. 2d 780 (5th Cir. 1958) .......5,12

Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., 280 F. 2d 531

(5th Cir. 1960) ........................ .................................. 5

Browder v. Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707 (M. D. Ala. 1956),

atf’d 352 U. S. 903 ....................................................... 9

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 191 F. Supp.

871 (E. D. La. 1961), aff’d sub nom. Legislature of

Louisiana v. United States, 367 U. S. 908 .................. 13

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 194 F. Supp. 182

(E. D. La, 1961), aff’d 368 U. S. 11 ......................... 11

Cantwell v. Connecticut, 310 U. S. 296 ......................... 5

Cleary v. Bolger, 371 U. S. 392 .............. ..... .........14,15,16

Crandall v. Nevada, 6 Wall. 35 ..................................... 5

Denton v. City of Carrollton, Georgia, 235 F. 2d 481

(5th Cir. 1956) .............................. .............. ............... - 13

Douglas v. Jeannette, 319 U. S. 157......................7, 8,10,14

II

PAGE

Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160 ......................... 5

Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 U. S. 229 ................. 5

Evers v. Dwyer, 358 U. S. 202 ..................................... 12

Harrison v. NAACP, 360 U. S. 167 .............................. 13

Jordan v. Hutcheson, 4th Cir., September, 1963 .......... 13

Julian v. Central Trust Co., 193 U. S. 9 3 ...................... 13

Looney v. Eastern Texas E. Co., 247 U. S. 214............ 13

McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 668 ............ 9,13

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501............... ..................... 17

Monroe v. Pape, 365 U. S. 167........................................ 5, 9

Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S. 373 ............................. 5

Morrison v. Davis, 252 F. 2d 102 (5th Cir. 1958) .... 10

Murdock v. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, 319 U. S.

105 .................................................................................. 8

Stefanelli v. Minard, 342 U. S. 117......................... 14,15,16

Stromberg v. California, 283 U. S. 359 ......................... 5

Terrace v. Thompson, 263 U. S. 197 ............................ . 16

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516 ................................. 5

Turner v. Memphis, 369 U. S. 350 ................................. 12

United States v. Wood, 295 P. 2d 772 (5th Cir. 1961) 10

Wolf v. Colorado, 338 U. S. 25 ..................................... 15

F edekal S ta t u t e s

28 United States Code, §2281 ........................................ 12

28 United States Code, §2283 ........................................ 13

42 United States Code, §1983 ..................................... 8, 9,10

Mnxtvb States (Burnt uf Appeals

F or t h e F if t h C ircuit

No. 20,823

J o h n R obert Z elln eb , et al.,

Appellants,

A l L ingo , Director of Public Safety for the

State of Alabama, et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

NORTHERN DIVISION

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

Appellants filed a complaint on May 3, 1963 in the United

States District Court for the Middle District of Alabama,

Northern Division, against appellee Al Lingo, Director of

Public Safety for the State of Alabama. Jurisdiction of

the trial court was based on Title 28, United States Code,

§1343(3); Title 42, United States Code, §1983 and Article

I, Section 8, Clause 3 of the Constitution of the United

States. -

Because the case was disposed of on motion to dismiss,

the allegations of the complaint will be stated as if they

were proved to have occurred.

2

Appellee, the Safety Director for the State of Alabama,

and his agents, acting under color of statutes, ordinances

and regulations of the State of Alabama, threatened ap

pellants with deprivation of rights, privileges and immu

nities secured by the Constitution of the United States

(E. 2) under the following circumstances:

Appellants, Negro and white persons, had begun a

“Freedom Walk” from Chattanooga, Tennessee to Jackson,

Mississippi on May 1, 1963 as a memorial to one William

Moore who was shot and killed near Gadsden, Alabama on

April 23, 1963, while walking along the highway with signs

urging an end to segregation (E. 4). Carrying signs con

cerning equal rights, they intended to walk along U. S.

Boute 11, two abreast at fifteen foot intervals, clear of and

facing vehicular traffic, obedient to all traffic and other

laws (E. 4-5). Upon the public announcement of appel

lants’ plans, appellee ordered the appellants’ arrest on

charges of breach of the peace if they entered Alabama

while on this walk (E. 5). Eight persons participating

in a “ Freedom Walk” had already been arrested in Etowah

County near Attalla, Alabama on May 1, 1963 (E. 5). The

complaint alleged that appellants’ arrest and prosecution

under these circumstances violated their constitutional

rights under the due process, equal protection and privi

leges and immunities clauses of the Fourteenth Amend

ment, as well as their rights under Article I, Section 8,

Clause 3, of the Constitution of the United States (E. 5).

Appellants sought a temporary restraining order and a

preliminary and permanent injunction enjoining appellee,

his agents, subordinates, employees, attorneys and succes

sors, and all persons in active concert and participation

with him from interfering, by arrest, prosecution, and im

prisonment, with appellants’ constitutionally protected

right to walk peacefully along the public highways in the

3

State of Alabama, thereby expressing their views on racial

segregation (E. 6-8).

Between 2:30 and 2 :45 P.M., May 3, 1963, appellants

were arrested at the direction of appellee A1 Lingo, Direc

tor of Public Safety for the State of Alabama and charged

with breach of the peace. On May 7, 1963, appellees Rich

mond Flowers, Attorney General of the State of Alabama

and Gordon Madison, Assistant Attorney General of Ala

bama, sought and obtained from the Circuit Court of

Dekalb County, without prior notice to appellants nor to

the organizations mentioned below, a temporary injunc

tion against appellants herein and the Congress of Racial

Equality, a New York corporation, the Student Non-

Violent Coordinating Committee, an unincorporated as

sociation with its principal place of business in Atlanta,

Georgia, and the National Association for the Advance

ment of Colored People, a New York corporation (R. 15-16,

22-23, 26-27, 28-29). Said injunction enjoined and re

strained appellants and the above-named organizations

from “any acts designated in the petition, particularly:

engaging in, sponsoring, or encouraging so-called ‘Free

dom Walks’ and from performing acts reasonably calcu

lated to cause breaches of the peace in Dekalb County,

Alabama, and from doing any acts designed to consummate

conspiracies to engage in said unlawful acts which are

reasonably calculated to cause a breach of the peace in

Dekalb County, Alabama” (R. 15-16, 25, 29). In the peti

tion for injunction submitted to the Circuit Court of De

kalb County, Attorney General Flowers alleged that

“ ‘Freedom Walks’ are not bona Me activities but are cal

culated to gain national publicity and to foment violence

and to cause breaches of the peace within the State of

Alabama and within this county, and that such activities

have constituted a breach of the peace” (R. 26).

4

May 18, 1963, appellants filed an amended and supple

mental complaint adding additional plaintiffs and defen

dants and instituting a class action on behalf of themselves

and others similarly situated. Motions to dismiss were

sustained against this complaint and its allegations must,

therefore, be taken as true for purposes of this appeal.

The supplemental complaint alleged that the detention of

appellants by appellees Richards, Colvard, Holman and

others acting under their control, impaired the exercise of

constitutionally protected rights; viz., to walk peacefully

through the State of Alabama upon the public highways, to

freedom of speech and protest against racial injustice, to

equal protection of the laws of the State of Alabama and the

privileges and immunities of United States citizens (R. 17).

Appellants further averred in their supplemental com

plaint that the injunctive decree issued by the Circuit

Court of Dekalb County was an interference with, an im

pediment to, and in contravention of, the already existing

jurisdiction of the United States District Court for the

Middle District of Alabama, Northern Division (R. 16).

Appellants, on behalf of themselves and others similarly

situated, filed an amended motion for preliminary injunc

tion seeking to enjoin appellees from continuing to inter

fere, by arrest, prosecution and imprisonment, with the

constitutionally protected right to walk peacefully along

the public highways of the State of Alabama and to restrain

appellees from enforcing the state court injunction issued

by the Circuit Court of Dekalb County (R. 18-19, 30-31).

Appellees, assigning various grounds in support, all filed

separate motions to dismiss the complaint (R. 32-40). On

June 19, 1963 Judge Frank M. Johnson, Jr., United States

District Judge, dismissed the complaint for want of equity

(R. 43, 45-47), reported at 218 F. Supp. 513. Notice of

Appeal was filed July 9, 1963 (R. 50-51).

5

Specification o f Error

The court below erred in dismissing appellants’ com

plaint, because appellants established a federal cause of

action in equity.

A R G U M E N T

The Court Below Erred in Dismissing Appellants’ Com

plaint, Because Appellants Established a Federal Cause

o f Action in Equity.

Appellants announced that they planned to set out upon

a “ Freedom Walk” to commemorate the death of William

Moore, who had been shot and killed while engaged in this

act of protest against racial discrimination. Beyond ques

tion, appellants’ protest was protected by the Constitution.

It was an exercise of First and Fourteenth Amendment

rights. Edwards v. South Carolina, 372 IT. S. 229; Strom-

berg v. California, 283 U. 8. 359; Cantivell v. Connecticut,

310 IT. S. 296. Moreover this protest invoked other con

stitutional protections, such as the protection afforded

movement through the states without arbitrary arrest and

harassment, Edwards v. California, 314 U. S. 160; Cran

dall v. Nevada, 6 Wall. 35, and the protection afforded

travel in interstate commerce, Morgan v. Virginia, 328 U. S.

373.

Because they were engaged in the exercise of consti

tutionally protected expression, they were not subject to

interference by state authorities seeking to prevent expres

sion of their views. State interference, whether by arrest,

Baldwin v. Morgan, 251 F. 2d 780 (5th Cir. 1958); Boman

v. Birmingham Transit Co., 280 F. 2d 531 (5th Cir. 1960);

cf. Monroe v. Pape, 365 IT. S. 167; prosecution, Edwards v.

South Carolina, 372 IT. S. 229; conviction or injunction,

Thomas v. Collins, 323 U. S. 516, would obviously run afoul

of the Fourteenth Amendment.

6

Therefore when the Safety Director for the State of

Alabama, A1 Lingo, announced that upon appellants’ en

trance into Alabama they would be arrested, placed in jail,

and charged with breach of the peace, appellants—prior

to crossing the border—filed this suit in the United States

District Court for the Middle District of Alabama to pre

vent appellee Lingo from carrying out his threat.

Appellants entered the state of Alabama and while con

tinuing to act peacefully and in the exercise of constitu

tionally protected rights of free expression were arrested

by appellee Lingo. Upon arrest, appellants were taken to

the DeKalb County Jail, Port Payne, Alabama and were

charged with “ conduct calculated to provoke a breach of

the peace.” On May 7, 1963, appellee Flowers, Attorney

General of Alabama, and his Assistant, Gordon Madison,

petitioned the Circuit Court of DeKalb County for a writ

of injunction against appellants and a number of organi

zations alleged to be connected with them. A temporary

injunction was issued without prior notice, as prayed for.

The arrests and the issuance of the injunction effectively

frustrated appellants’ desire to conclude their “ Freedom

Walk” . The exercise of their constitutional rights was, and

continues to be, restrained.

In order to further assert and protect their constitutional

rights appellants filed a supplemental complaint in the

United States District Court and brought to the Court’s

attention these additional events which had occurred sub

sequent to the filing of the original complaint. Appellants

asked that the actions which state authorities had taken

to prevent completion of the “Freedom Walk” be enjoined.

This the District Court refused to do and, in this refusal,

we submit its action was erroneous.

7

The District Court held that it possessed jurisdiction

(218 F. Supp. at 515). Moreover the District Court strongly

suggested that appellants’ view of their substantive rights

under United States Supreme Court decisions was cor

rect (218 F. Supp. at 518). Moreover, the District Court

was strongly critical of appellees for having interfered

with these rights. The Court said:

The action now being taken by this Court in refusing

to enjoin the criminal prosecution of these plaintiffs

by officers acting under color of law for the State of

Alabama must not be construed as an approval of

the action taken by these officers in arresting and

prosecuting these plaintiffs under the guise of main

taining and preserving the peace and tranquility of

the State of Alabama. 218 F. Supp. at 518. (Emphasis

supplied.)

The District Court also was critical of appellees for

having “ run” to the Circuit Court of DeKalb County (218

F. Supp. at 518).

The District Court, however, refused, as an exercise of

comity and equitable discretion, to grant an injunction,

relying upon Douglas v. Jeannette, 319 U. S. 157.

In this we submit the Court below erred and the judg

ment should be reversed.

Douglas v. Jeannette held that federal courts, as a mat

ter of comity and equitable discretion, should not interfere

with state criminal proceedings and law enforcement offi

cials when an adequate remedy is provided in the state

proceedings for the protection and assertion of all consti

tutional rights. But, the Court recognized that its holding

could not be applied mechanically and that circumstances

in which a substantial federal interest was presented would

8

compel federal courts to act. 319 U. S. at 164. Moreover,

an injunction against enforcement of the ordinance in

volved there was unnecessary because, in parallel litigation,

the Supreme Court had already adjudicated that the ordi

nance was unconstitutional. Murdoch v. Commonwealth of

Pennsylvania, 319 U. S. 105.

The District Court, in denying relief, failed we submit to

give adequate recognition to the paramount federal inter

est embodied in 42 U. S. C. §1983, and invoked here. The

Court failed to recognize that Douglas v. Jeannette does not

require Negroes to pursue a tortuous path through unsym

pathetic state courts in order to vindicate clear constitu

tional guarantees.

As Judge Rives, of this Court, said in dissent in Bailey

v. Patterson, 199 F. Supp. 595, 616 (S. D. Miss. 1961),

rev’d 369 U. S. 31:

An exception to Jeannette has developed in favor of

class actions on behalf of Negroes combating state sup

ported segregation . . . Actually this is not so much an

exception as a practical application of the Jeannette

requirement of “adequacy.” For the alternative to this

suit [suit to enjoin enforcement of Mississippi “ peace

statutes” and statutes requiring racial segregation on

common carriers] is that a great number of individual

Negroes would have to raise and protect their constitu

tional rights through the myriad procedure of local

police courts, county courts and state appellate courts

with little prospect of relief1 before they reach the

United States Supreme Court.

1 The prospect of relief here is illustrated by the concurrence

of the Circuit Court of DeKalb County in Attorney General

Flowers’ assertion that “ ‘Freedom Walks’ are not bona fide ac

tivities . . . and [constitute] a breach of the peace” (R. 26).

9

Cases decided by this and other courts support the propo

sition that notions of comity should not be permitted to

subvert the high Federal purposes of Section 19832 and

that comity “has no application where the plaintiffs com

plain that they are being deprived of constitutional civil

rights, for the protection of which the Federal Courts have

a responsibility as heavy as that which rests on the State

Courts.” Browder v. Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707, 713 (M. D.

Ala. 1956), affirmed 352 U. S. 903.

This Court has seen in Browder v. Gayle, 142 F. Supp.

707 (M. D. Ala. 1956), affirmed 352 U. S. 903, a rejection

2 The purposes of Section 1983 were recently reviewed in McNeese

v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 668, and found to be the fol

lowing: to override certain kinds of state laws; to provide a

remedy where state law was inadequate; to provide a federal

remedy where the state remedy, though adequate in theory, was

not available in practice; and to provide a remedy in the federal

courts supplementary to any remedy any state might have.

In holding that exhaustion of state remedies was not a pre

requisite to maintaining a suit under Section 1983 to eradicate

segregation in the public schools, the Court said:

We would defeat those purposes if we held that assertion of

a federal claim in a federal court must await an attempt to

vindicate the same claim in a state court. 373 U. S. at 672.

Mr. Justice Frankfurter, in his separate opinion in Monroe v.

Pape, 365 U. S. 167, saw Section 1983 as being intended by the

Congress which enacted the original sections (R. S. §1979 and

Section 1 of the Ku Klux Act of April 20, 1871) to grant a sub

stantive right to the exercise of federal jurisdiction:

. . . the theory that the Reconstruction Congress could not have

meant §1979 principally as a ‘jurisdictional’ provision grant

ing access to an original federal forum in lieu of the slower,

more costly, more hazardous route of federal appeal from

fact-finding state courts, forgets how important providing a

federal trial court was among the several purposes of the

Ku Klux Act.

. . . Section 1979 does create a ‘substantive’ right to relief,

but this does not negative the fact that a powerful impulse

behind the creation of this ‘substantive’ right was the purpose

that it be available in, and be shaped through original federal

tribunals. 365 U. S. at 251-252.

10

of the application of comity to cases arising under 42

U. S. C. §1983. In Morrison v. Davis, 252 F. 2d 102, 103

(5th Cir. 1958), this Court said, in enjoining enforcement

of state penal statutes requiring segregation in transporta

tion facilities:

That case [Browder v. Gayle] disposes of the contention

that the federal court should not grant an injunction

against the application or enforcement of a state stat

ute, the violation of which carries criminal sanctions.

This is not such a case as requires the withholding of

federal court action for reason of comity, since for the

protection of civil rights of the kind asserted Congress

has created a separate and distinct federal cause of

action. 42 U. S. C. A. §1983. Whatever may be the rule

as to other threatened prosecutions, the Supreme Court

in a case presenting an identical factual issue affirmed

the judgment of the trial court in the Browder case in

which the same contention was advanced. To the ex

tent that this is inconsistent with Douglas v. City of

Jeannette, Pa., 319 U. S. 157, 63 S. Ct. 877, 87 L. Ed.

1324, we must consider the earlier case modified.

United States v. Wood, 295 F. 2d 772 (5th Cir. 1961),

cert, denied 369 U. S. 850, was a suit by the Federal Gov

ernment for injunctive relief against the prosecution of a

Negro for breach of the peace. The Government contended

that the State prosecution was designed to and would intimi

date qualified Negroes from attempting to register to vote.

The United States District Court for the Southern District

of Mississippi denied relief, relying on Douglas v. Jeannette,

319 U. S. 157. This Court reversed, holding Douglas v.

J eannette inapplicable to a suit brought by the government

under 42 U. S. C. A. §1971, and relying upon Morrison v.

Davis, 252 F. 2d 102 (5th Cir. 1958), cer. denied 356 U. S.

968.

11

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 194 F. Supp. 182

(E. D. La, 1961), affirmed 368 U. S. 11, was a suit to en

join enforcement of Louisiana statutes punishing the newly

created crime of giving or receiving anything of value as an

inducement to sending one’s child to a school operated in

violation of the law of Louisiana, i.e., an integrated school.

Louisiana’s Attorney General admitted to the Court that

the statutes were probably void for vagueness but insisted

that the proper test of the statutes should come in the state

court, after an accused had been arrested, held and charged

under the statutes. To this the Court replied:

True, “ it is a familiar rule that courts of equity do

not ordinarily restrain criminal prosecutions.” Doug

las v. City of Jeannette, 319 U. S. 157, 163, 63 S. Ct.

877, 881, 87 L. Ed. 1324. And this principle has special

force when application is made to a federal court to

enjoin the enforcement of state criminal statutes, for

then considerations of comity add their weight to sug

gest abstention. Beal v. Missouri Pacific R. Co., 312

U. S. 45, 49-50, 61 S. Ct. 418, 85 L. Ed. 2d 1152. But

the rule cannot be applied mechanically. N. A. A. C. P.

v. Bennett, 360 U. S. 471, 79 S. Ct. 1192, 3 L. Ed. 2d

1375; cf. Doud v. Hodge, 350 LT. S. 485, 76 S. Ct. 491,

compel a federal court to act, Truax v. Raich, 239 U. S.

33, 36 S. Ct. 7, 60 L. Ed. 131; Pierce v. Society of

Sisters, 268 IT. S. 510, 45 S. Ct. 571, 69 L. Ed. 1070;

Hague v. Committee Industrial Organization, 307 IT. S.

496, 59 S. Ct. 954, 83 L. Ed. 1423; see Terrace v. Thomp

son, 263 U. S. 197, 214, 44 S. Ct. 15, 68 L. Ed. 255;

Packard v. Banton, 264 IT. S. 140, 143, 44 8. Ct. 257,

68 L. Ed. 596; Spielman Motor Co. v. Dodge, 295 U. S.

89, 95, 55 S. Ct. 678, 79 L. Ed. 1322; Beal v. Missouri

Pacific R. Co., supra, at page 50, 61 S. Ct. 418; Douglas

v. City of Jeannette, supra, at page 163, 63 S. Ct. 882;

12

Denton v. City of Carrollton, Georgia, 5 Cir., 235 F. 2d

481, 484-485. This is such a case.

Recently this Court, in Anderson v. City of Albany (5th

Cir. July 26, 1963), reversed the dismissal of a complaint

asking an injunction against the enforcement of certain

segregation practices. In addition, this Court held that

upon the record the trial court was without discretion to

deny the injunction sought and, therefore, this Court di

rected that, upon remand, an injunction issue substantially

as prayed for. This Court commanded that enforcement of

segregation, either directly through the attacked city ordi

nances or indirectly through breach of the peace prosecu

tions, be enjoined by the trial court.

These cases indicate that federal courts will not, and

should not, forebear to enjoin threatened state prosecu

tions when clear Fourteenth Amendment rights are put in

jeopardy. One should not be required to subject himself to

arrest and prosecution in order to vindicate his clear con

stitutional rights. Evers v. Divyer, 358 U. S. 202, 204;

Baldwin v. Morgan, 251 F. 2d 780, 787 (5th Cir. 1958).

Moreover, it may be demonstrated that the entire de

velopment of constitutional jurisprudence has eschewed

federal abstention of various sorts which ordinarily would

apply.

For example, 28 U. S. C. §2281 provides for additional

protection when a litigant seeks to enjoin enforcement of

a state policy in the federal courts. Three judges must sit

and determine such a cause. But when Fourteenth Amend

ment rights of the type involved here are at issue and the

outcome is obvious, only one judge need sit. Bailey v. Pat

terson, 369 U. 8. 31; Turner v. Memphis, 369 U. S. 350.

It should be noted that Bailey v. Patterson is very much

13

in point because in that case a “Freedom Ride” was being-

conducted for much the same purpose as the “Freedom

Walk” in this suit.

Moreover, federal courts often will defer to the state

judiciary when the construction of a state statute is in

volved and construction of that statute will save the fed

eral judiciary from having to decide a constitutional ques

tion. Harrison v. NAACP, 360 U. S. 167. But where the

meaning of the statute is obvious and but one result can

be foreseen, the federal courts will hear and determine the

issue. McNeese v. Board of Education, 373 U. S. 668.

Another example of federal abstention which might ordi

narily be applied is the policy which restrains federal courts

from enjoining state legislatures. Yet this has been done

when clear constitutional rights have been infringed. Jor

dan v. Hutcheson, 4th Cir., September, 1963; Bush v. Or

leans Parish School Board, 191 F. Supp. 871 (E. D. La.

1961), affirmed sub nom. Legislature of Louisiana v. United

States, 367 U. S. 908, and cases cited.

Perhaps the best-defined stricture against federal inter

ference with state government is that embodied in 28

U. S. C. §2283. That section inhibits federal courts from

granting injunctive relief against state court proceedings.

Yet such relief has been granted when a paramount federal

interest was demonstrated. Julian v. Central Trust Co.,

193 U. S. 93; Looney v. Eastern Texas R. Co., 247 U. S. 214.

This Court has held Section 2283 to be no bar to an

action by a labor organizer and his union to enjoin a

municipality from instituting criminal proceedings under

an ordinance requiring any person engaged in the occupa

tion of labor union agent to pay an exorbitant tax. In the

case of Denton v. City of Carrollton, Georgia, 235 F. 2d

481 (5th Cir. 1956), this Court reversed the district court’s

14

refusal to grant an injunction. To the district court’s as

sertion that the case was wanting in equity under the prin

ciples of Douglas v. Jeannette, this Court replied:

But this wholesome rule envisages itself the neces

sity, under circumstances of genuine and irretrievable

damage, for affording equitable relief even though the

result is to forbid criminal prosecution or other legal

proceedings (235 F. 2d at 485).

The other cases relied upon by Judge Johnson, Stefanelli

v. Minard, 342 U. S. 117, and Cleary v. Bolger, 371 U. S.

392, are inapposite. The ratio decidendi of both cases was

the federal policy against piecemeal review.

Both Cleary and Stefanelli involved questions concerning

the validity of the introduction of evidence in a state court

proceeding. The federal court determination in Cleary or

Stefanelli would not have arrested the state court proceed

ings, since the federal court was only to rule on a collateral

issue. The state court would have continued with the trial

following a ruling on the evidentiary question. Some jus

tification existed, then, for the fear of conflict between

state and federal courts and an “ intrusion of the federal

courts in the administration of the criminal law.” Stefanelli

v. Minard, 342 U. S. 117, 120. The danger of piecemeal

review was thus described in Stefanelli:

[W]e would expose every state criminal prosecution

to insupportable disruption. Every question of pro

cedural due process of law—with its far-flung and un

defined range—would invite a flanking movement

against the system of state courts by resort to the

federal forum, with review if need be to this court,

to determine the issue. Asserted unconstitutionality

in the impaneling and selection of the grand and

petit juries, in the failure to appoint counsel, in the

15

admission of a confession, in the creation of an unfair

trial atmosphere, in the misconduct of the trial court

■—all would provide ready opportunities, which con

scientious counsel might be bound to employ, to sub

vert the orderly, effective prosecution of local crime

in local courts (342 U. S. at 123-124).

Moreover, the decision in Stefanelli, it is submitted, was

controlled by the doctrine of Wolf v. Colorado, 338 U. S. 25.

Justices Warren and Brennan made this point in their

dissent in Cleary:

In invoking the bogey of federal disruption of state

criminal processes, the court relies heavily on Stefa

nelli, where it was held to be improper to enjoin the

introduction in a state criminal trial of evidence seized

by state officers in violation of the Fourteenth Amend

ment. But Stefanelli is manifestly inapt. That deci

sion was compelled by Wolf v. Colorado . . . where the

Court, while confirming that the Fourth Amendment

had been absorbed into the Due Process Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment, nevertheless left the states

free to devise appropriate remedies for violations of

this constitutional protection. To have authorized the

Federal District Courts to order the exclusion in state

criminal trials of evidence unlawfully obtained by state

officials would have sanctioned accomplishing indirectly

what Wolf forbade directly (371 U. S. at 411).

Again, in Cleary the Court was obviously concerned with

the danger of piecemeal litigation due to the federal courts’

determination of collateral issues incident to a state court

criminal proceeding. Justice Harlan, writing the majority

in Cleary, stated:

16

To permit such claims to be litigated collaterally, as

is sought here, would in effect frustrate the deep-

seated federal policy against piecemeal review (371

IT. S. at 401).

Thus Stefanelli and Cleary are no precedent for the

withholding of federal relief in a case such as this, where

complete and speedy justice can be effected in the federal

forum.

Finally, it should be noted that the Supreme Court on

numerous occasions has been willing to uphold injunctive

relief to support property rights. Often quoted is the fol

lowing passage from Terrace v. Thompson, 263 U. S. 197,

214-216:

The unconstitutionality of a state law is not of itself,

ground for equitable relief in the courts of the United

States. That a suit in equity does not lie where there

is a plain, adequate and complete remedy at law

is so well understood as not to require the citation

of authorities. But the legal remedy must be as com

plete, practical, and efficient as that which equity could

afford. . . . Equity jurisdiction will be exercised to

enjoin the threatened enforcement of a state law which

contravenes the Federal Constitution wherever it is

essential, in order effectually to protect property rights

and the rights of persons against injuries otherwise ir

remediable; and in such a case a person who, as an

officer of the state, is clothed with the duty of enforc

ing its laws, and who threatens and is about to com

mence proceedings, either civil or criminal, to enforce

such a law against parties affected, may be enjoined

from such action by a federal court of equity. . . .

[Appellants] are not obliged to take the risk of prose

cution, fines, and imprisonment and loss of property

17

in order to secure an adjudication of their rights. The

complaint presents a case in which the equitable relief

may be had, if the law complained of is shown to be

in contradiction of the Federal Constitution.

First Amendment rights should receive no less protection.

See Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U. S. 501, 509.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the order of the court be

low dismissing appellants’ complaint should be reversed

and the cause remanded to that court for further pro

ceedings.

Respectfully submitted,

F eed D . G ra y

34 North Perry Street

Montgomery, Alabama

J a c k G reen berg

C o n sta n c e B a k e r M o tle y

D e r r ic k A. B e l l , J r .

N o r m a n C. A m a k er

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Attorneys for Appellants

3 8