Breakthrough in Miss. School Bigotry Scored

Press Release

March 6, 1964

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 1. Breakthrough in Miss. School Bigotry Scored, 1964. 5184bdcd-b492-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/56961bd5-067b-416a-920f-d6973218f01f/breakthrough-in-miss-school-bigotry-scored. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

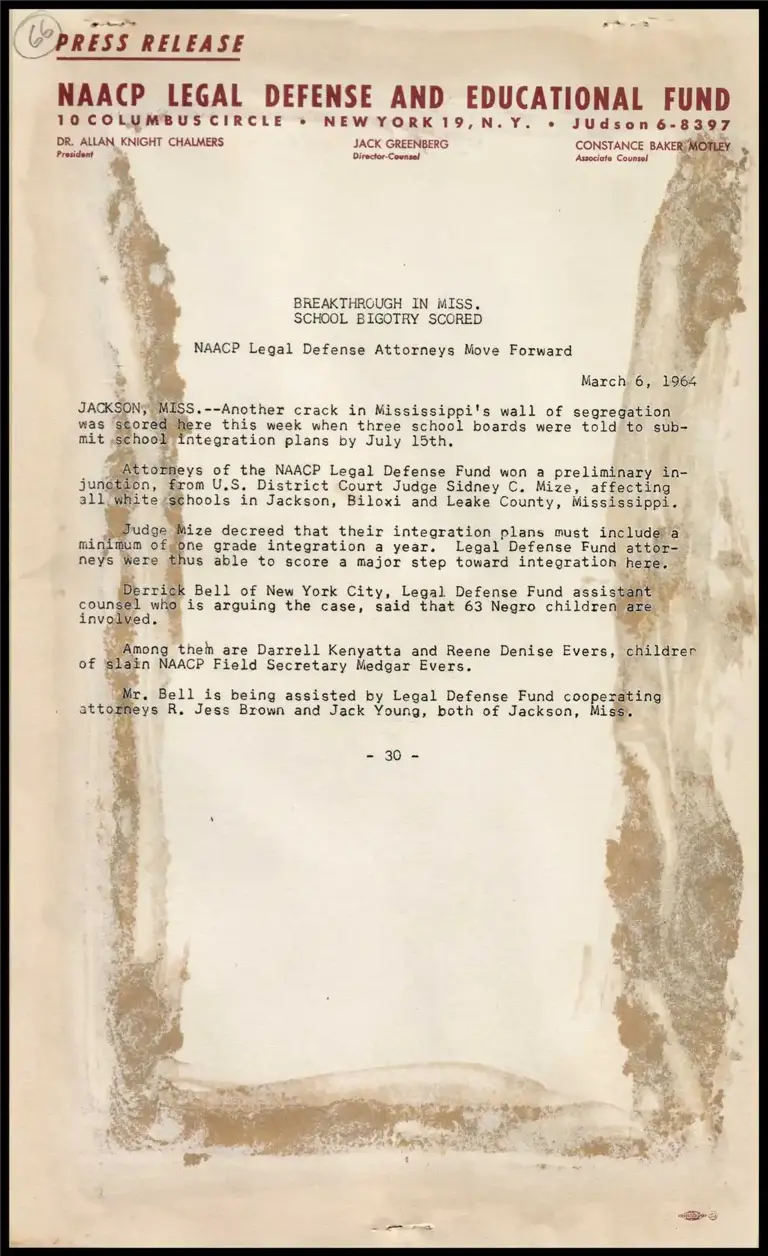

(W°PRESS RELEASE oe

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

TOCOLUMBUS CIRCLE * NEWYORK19,N.Y. © JUdson 6-83 97

DR. ALLAN KNIGHT CHALMERS JACK GREENBERG CONSTANCE BAKER%,

President © Director-Counsel Associate Counsel

a,

SCHOOL BIGOTRY SCORED :

BREAKTHROUGH IN MISS. 3

NAACP Legal Defense Attorneys Move Forward

March 6, 1964

SS.--Another crack in Mississippi's wall of segregation

was * oxeeer® this week when three school boards were told to sub-

mit school integration plans by July 15th,

sneys of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund won a preliminary in-

rom U.S, District Court Judge Sidney C. Mize, affecting

hools in Jackson, Biloxi and Leake County, Mississippi.

“Mize decreed that their integration plans must includet ¢ 5

Ne grade integration a year. Legal Defense Fund att

us able to score a major step toward integration he

BS

Bell of New York City, Legal Defense Fund assis

e! wi is arguing the case, said that 63 Negro childre

red. =

(mong then are Darrell Kenyatta and Reene Denise Evers, childrer

ain NAACP Field Secretary Medgar Evers.

r. Bell is being assisted by Legal Defense Fund cooper

eys R. Jess Brown and Jack Young, both of Jackson, Mi