Richmond County Georgia Board of Education v Acree Brief of Opposition to Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1972

14 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Richmond County Georgia Board of Education v Acree Brief of Opposition to Certiorari, 1972. 1eeae561-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/56a943a6-6f44-489f-b37c-23a69f7ea44d/richmond-county-georgia-board-of-education-v-acree-brief-of-opposition-to-certiorari. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

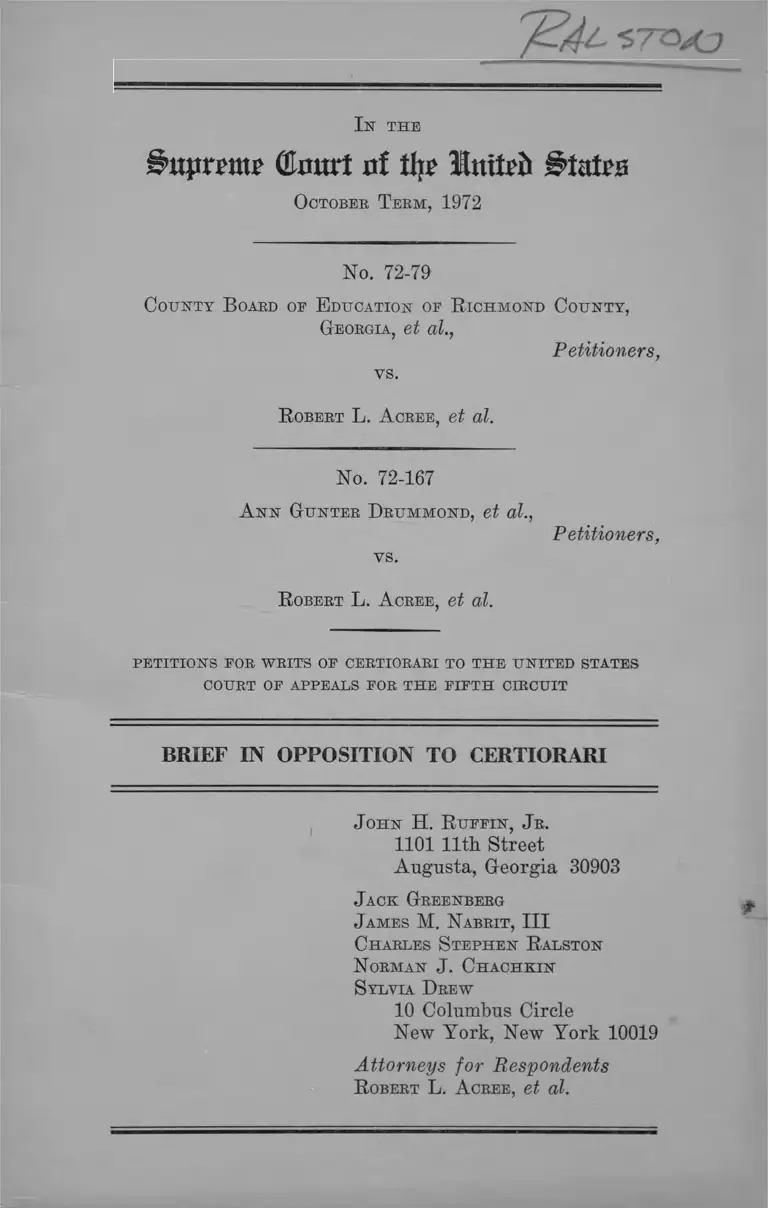

^-STZVO

1st the

(£mxt of % Htttteb Platts

October T erm, 1972

No. 72-79

County B oard oe E ducation oe R ichmond County,

Georgia, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

R obert L. A cree, et al.

No. 72-167

A nn Gunter Drummond, et al.,

vs.

Petitioners,

R obert L. A cree, et al.

P E T IT IO N S FO R W R IT S OE C E R T IO R A R I TO T H E U N IT E D ST A T E S

C O U R T OF A P P E A L S F O R T H E F IF T H C IR C U IT

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

J ohn H. R uffin, Jr.

1101 11th Street

Augusta, Georgia 30903

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Charles Stephen R alston

Norman J. Chachkin

Sylvia Drew

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Respondents

R obert L. A cree, et al.

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions Below ................................................................. 1

Jurisdiction ....................................................................... 2

Questions Presented ..................... 2

Statement ........................................................................... 2

Reasons Why the Writs Should Be Denied.................. 3

Conclusion.......................................................... 6

A ppendix A ............................................. la

I n th e

i a t y n w (U m trt a f tit? Iln ita jb 0 t a i i ^

Octobee T eem, 1972

No. 72-79

County B oaed oe E ducation of R ichmond County,

Georgia, et al.,

Petitioners,

vs.

R obebt L. A ceee, et al.

No. 72-167

A nn Gunter Drummond, et al.,

vs.

Petitioners,

R obebt L. A cree, et al.

P E T IT IO N S FO B W R IT S OF C E R T IO R A R I TO T H E U N IT E D ST A T E S

C O U RT OF A P P E A L S F O R T H E F IF T H C IR C U IT

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

Opinions Below

The opinion of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit is reported at 458 F.2d 486 and the opin

ion of the United States District Court for the Southern

District of Georgia at 336 F. Supp. 1275.

2

Jurisdiction

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U.S.C. §1254(1).

Questions Presented

These two petitions for writs of certiorari to review the

same judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fifth Circuit, one filed by the school authorities of

Richmond County, Georgia and one filed by a group of

white parents who intervened in this school desegregation

action which had been pending since 1964, each present

basically the same claim: that the order of the district

court, as affirmed by the Court of Appeals, directing im

plementation of a pupil desegregation plan of which trans

portation was an integral part is unauthorized by the prin

ciples elucidated in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board

of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) because (a) the plan is

projected to achieve at each elementary school a student

body of racial composition so nearly identical as to merit

description as a “racial balance” plan; and (b) the time,

distance and expense of the transportation which would be

required to implement the order is so great as to be beyond

the sort of plans contemplated by this Court in Swann.

The petition in No. 72-167 also raises certain questions

with respect to a recently enacted statute which have never

been presented to any court in the context of this case and

which, in any event, have no bearing upon this case.

Statement

We shall not belabor the facts by adding materially to the

already lengthy statements set out in the Petitions; the

clearest and most cogent description of the history of this

3

school desegregation case is to be found in the district

court’s order, reprinted at pages A-7 through A-32 of the

Appendix to the Petition in No. 72-167.

After this Court’s decision in Swann, supra, a pending

appeal in the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit was remanded to the district court with instruc

tions “forthwith to constitute and implement a student and

faculty assignment plan that complies with the principles

established in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of

Education . . . ” Acree v. County Board of Education, 443

F.2d 1360. At that time, the public schools of Richmond

County, Georgia operated upon a strict geographic zoning

student attendance plan, under which traditionally black

and white schools retained their racial identities. (See 336

F. Supp. at 1277-78, Appendix to Petition in No. 72-167,

pp. A-12 through A-13). Following a series of conferences,

hearings, and opportunities afforded respondents to pre

pare and propose a desegregation plan for the Richmond

County schools which would meet constitutional standards,

(none of which were acted upon), the district court (pur

suant to the authority confirmed by Swann) appointed its

own experts to suggest alternative desegregation plans,

and approved one of such plans for implementation on a

phased basis, with complete implementation to occur effec

tive with the commencement of the 1972-73 school year.

All parties appealed and on March 31, 1972 the judgment

of which review is sought, affirming the district court order

with a modification only as to timing, was entered.

Reasons Why the Writs Should Be Denied

These petitions do little more than simply ask this Court

to overrule its decision in Swann because once again a

school board and some of its white patrons do not desire

effective desegregation of the public schools. The vaunted

4

“ racial balance” supposedly to be achieved by implemen

tation of the district court’s order is hardly the “wooden

resort to racial quotas” which this Court held in Swann

was not required to remedy the denial of Fourteenth

Amendment rights. See Drummond v. Acree, No. A-250

(September 1, 1972) (Mr. Justice Powell, Circuit Justice),

page 3.

Both Petitions list the overall population ratios of the

various zones within which individual schools are paired

(Petition in No. 72-79, pp. 9 and 10; Petition in No. 72-167,

p. 10) rather than demonstrating the variation between

the populations of each school. These are shown in the

projections submitted by the court-designated experts (re

printed at pp. A-39 through A-54 of the Appendix to the

Petition in No. 72-167). The individual schools are pro

jected to range from 28.7% black (p. A-48) to 50% black

(p. A-42). While this range is not quite so large as that

in Charlotte, it is Petitioners, and not the plaintiffs or

either of the Courts below, who are here exaggerating

numbers far beyond their significance.

Whatever one’s view of the range in racial breakdowns

among schools from 28 to 50%, the plan ordered imple

mented by the district court was not designed to come as

close to the system-wide ratio in Richmond County as

possible. In fact, it was not prepared from data listing

the race, residence and grade level of every student in the

system (which would have permitted its draftsmen to de

sign zones for individual or paired schools so as to bring

about a far closer tolerance among the various schools)

but was based simply upon combining the previously exist

ing zones for each school, which had been drawn by the

county school authorities, and altering their grade struc

tures through contiguous and non-contiguous pairing and

clustering, in accordance with their capacities and the need

to bring about some real desegregation.

5

Frankly, it is difficult to understand the exaggerated

claims in both Petitions that this is a racial balance plan.

The explicit holdings to the contrary by both courts below

are clearly correct; the mandates of this Court in Swann

received only respectful application by a district court oper

ating under great pressure and "without cooperative assis

tance from the school authorities,1 and a Court of Appeals

intimately familiar with the issues in school desegregation

cases.

In a similar vein, the Petitions are filled with claims that

the transportation of school children required under this

plan is far greater in distance, time and expense than that

approved by the Court in Swann. Curiously there is not

a single reference to any evidence concerning these matters

in either Petition but merely the sort of ad hoc claim that

a round trip of 11.8 miles in Richmond County will take

two hours a day (Petition in No. 72-79, p. 8). There may

be some practical problems in implementing the desegre

gation plans, but not only will “a good faith effort by the

school board . . . overcome any logistical problems that

might arise,” 458 F.2d at 488, but neither the decree of the

district court nor the judgment of the Court of Appeals

in any way restricts the parties from seeking modifications

should insuperable, practical difficulties arise when the

plan is actually implemented. See Kelley v. Metropolitan

County Board of Education, No. 71-1778 (6th Cir., May 30,

1972) at pp. 22-25 (reprinted as Appendix A ).2

In short, none of the Petitioners have raised significant

claims of any substance to the effect that the lower courts

exceeded the equitable remedial powers described in Swann,

Here, as in Swann, the exercise of remedial authority by the

district court was prompted by the total default of school officials.

2 Thus intervenors should present any “less rending” (Petition in

No.̂ 72-167, p. 16) but equally effective elementary school desegre

gation plan to the district court.

6

and only the overruling of that unanimous decision could

justify altering the judgment below.

Finally, the Petitioners in No. 72-167 make some sugges

tions that Sections 805 and 806 of the Education Amend

ments of 1972, P.L. 92-138, somehow affect this litigation.

As to Section 805, there is not a whisper of a suggestion

in the Petition that the trial court employed any non-

uniform rule of evidence in reaching its result; and with

regard to Section 806, we are unable to fathom any sug

gestion in this Court’s Swann decision that it would not

apply its interpretation of 42 U.S.C. § 2000c-6 in any ap

propriate case no matter in what jurisdiction it arose. In

any event, that section applies or does not apply to this

case in exactly the same manner as it did in Swann.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, respondents Acree, et al.

respectfully pray that the writs of certiorari be denied.

Respectfully submitted,

J ohn H. R uffin, Jr.

1101 11th Street

Augusta, Georgia 30903

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Charles Stephen R alston

Norman J. Chachkin

Sylvia D rew

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Respondents

R obert L. A cree, et al.

APPENDIX

la

Appendix A to Brief in Opposition to Certiorari

Nos. 71-1778-79

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F ob the Sixth Circuit

R obert W . K elley, et al.,

H enry C. Maxwell, Jr., et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v.

Metropolitan County B oard of E ducation of Nashville

and Davidson County, T ennessee, C. R. D orrier,

Chairman, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants.

A P P E A L F R O M T H E U N IT E D ST A T E S D IST R IC T C O U RT FOR T H E

M ID D L E D IS T R IC T O F T E N N E S S E E , N A S H V IL L E D IV ISIO N

Decided and Filed May 30, 1972

Before:

E dwards, Celebrezze and McCree,

Circuit Judges.

# « * # *

III P ractical P roblems

If there is an appellate issue of substance in this appeal,

it is to be found in the practical problems which appellants

2a

claim have developed since the entry of the District Judge’s

order. Appellant summarizes these issues thus:

A plan which exposes the children in the school

system to undue danger to health and accident, inter

feres with their education by requiring excessive

periods of time on buses, causes them to leave home

before daylight or to return home after dark, exposes

them to the dangers of travel in old and inadequately

maintained equipment and causes elementary school

children, both black and white, to suffer hardships to

which young children should not be exposed can hardly

be termed feasible, workable, effective and realistic.

Substantial as these problems appear to be on the sur

face, there are two reasons why no relief can be granted

in this forum. The first is that no motion for relief per

taining to these facts has ever been filed by appellant in

the District Court. These statements at this point are al

legations and they are controverted by the appellee. This,

of course, is an appellate court—not a trial court. As appel

lants well know, the arena for fact-finding in the federal

courts is the United States District Court. Until these

claims have been presented in a trial court, with an oppor

tunity for sworn testimony to be taken and controverted

issues and facts decided by the processes of adversary

hearing, this court has no jurisdiction.3

s During the pendency of an appeal, jurisdiction of the case lies,

of course, in the appellate court. There is, however, familiar law

to deal with an unexpected problem which arises in this period

concerning the actual terms of the order or judgment under appeal.

The District Court may on being apprised of the problem and

having determined its substantiality (with or without hearing)

certify to the appellate court the desirability of a remand for com

pletion or augmentation of the appellate record. No memory in this

court encompasses a refusal of such a request.

The record is clear that no request for remand was made by

the District Court, obviously, at least in part, because appellants

made no motion for relief before the District Court.

3a

The second reason as to why appellants are entitled to no

relief on this issue probably serves to explain the first. The

entire “record” upon which appellant bases his plea for

relief as to practical problems is a “Report to the Court”

of Dr. Brooks, Director of Schools of the Metropolitan

County Board of Education. This report is dated Octo

ber 18, 1971, just over a month after the opening of school.

While we are advised that it was sent to the District Judge,

as we have noted, no motion of any kind seeking any Dis

trict Court action was ever filed concerning it. Even more

important, the statement on its face suggests that local

authorities in Nashville and Davidson County have not

made good faith efforts to comply with the order of the

District Judge.

Dr. Brooks’ affidavit does present this exculpatory ex

planation which serves to point in the direction of other

authorities as those responsible for the inconveniences and

hazards of which Dr. Brooks’ statement speaks. The state

ment says:

The School Board is fiscally dependent in that its

budgets must he approved by the Metropolitan City

Council. In approving the budget of the School Board

on June 30,1971, Council members demanded assurance

that no funds included in the budget would be used to

purchase buses for the purpose of transporting students

to establish a racial balance. The 1971-72 budget did

provide for the purchase of 18 large buses to replace

obsolete equipment to provide transportation for stu

dents to the new comprehensive McGfavock High School.

It is clear, however, that neither the Metropolitan City

Council or, for that matter, the Legislature of Tennessee

can forbid the implementation of a court mandate based

upon the United States Constitution. In a companion case

to Swann, supra, Chief Justice Burger, writing again for

4a

a unanimous court, held that an anti-busing law which

flatly forbids assignment of any student on account of race

or for the purpose of creating a racial balance or ratio in

the schools and which prohibits busing for such purposes,

was invalid as preventing implementation of desegregation

plans required by the Fourteenth Amendment. North Caro

lina State Board of Education v. Swann, 402 IT.S. 43, 45-46

(1971). See also Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958).

Dr. Brooks’ statement also furnishes the bus schedule of

the Metropolitan County Board of Education by yearly

models. It shows that the Board has an average of 18.9

buses for each of the last 10 model years. The 18 buses

purchased in 1971 were described by Dr. Brooks as “ to

replace obsolete equipment.” It appears from the Metro

politan Board’s own statements that the Board and the

local authorities in Nashville did not purchase one piece

of transportation equipment for the purpose of converting

the Metropolitan County Board of Education school system

from a dual school system segregated by race into a unitary

one, as called for by the District Judge’s order.

At court hearing we had been puzzled as to why counsel

for the Board had failed to go back to the District Court to

report on the grievous circumstances which he so strongly

alleged before us. Like most decrees in equity, an injunc

tive decree in a school segregation case is always subject

to modification on the basis of changed circumstances.

Sloan v. Tenth School District of Wilson County, 433 F.2d

587, 589-90 (6th Cir. 1970). Further acquaintance with the

record, which, of course, the District Judge would have

known in detail, leaves us in no further quandry as to the

reasons for counsel’s reluctance.

* * # # *

ME1LEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. 2)9