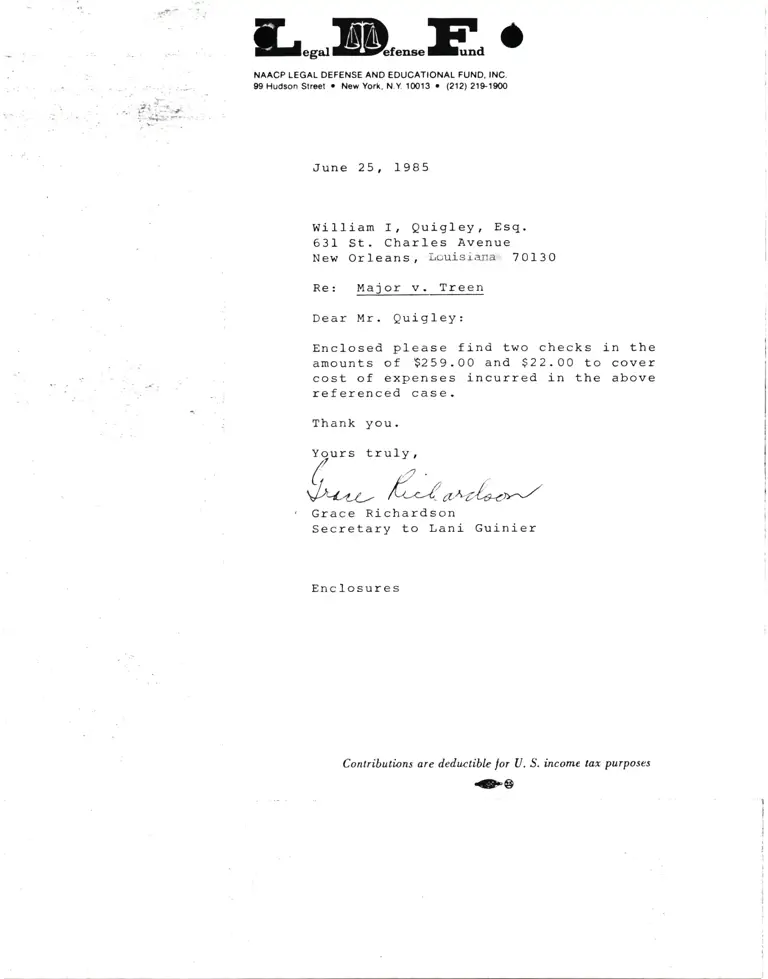

Correspondence from Grace Richardson to William Quigley, Esq. Re: Major v. Treen

Correspondence

June 25, 1985

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Correspondence from Grace Richardson to William Quigley, Esq. Re: Major v. Treen, 1985. fb34cf6a-e792-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/56f46577-8e9a-4fe9-a39c-6471f7ea9444/correspondence-from-grace-richardson-to-william-quigley-esq-re-major-v-treen. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

NAACP LEGAL OEFET{SE AND EDUCAT]ONAL FUNO, INC.

e0 Hud&n Stitct . l{cw Yort, N.Y. rq)13 e (212) 2t}1$t)

-v-- -

!* (a*

, Grace Richardson

June 25, 1985

William f, QuigIey, Esq.

63I St. Charles Avenue

New Orleans, r.c'uisian& 70130

Re: lla j or v. Treen

Dear Mr. Quigley:

Enclosed please find two checks

amounts of $259.O0 and $22.00 to

cost of expenses incurred in the

referenced case.

Thank you.

Yo-urs tru1y,

in the

cover

above

Secretary to Lani Guinier

Enc losures

Contributbns are dedrctibh lor U. S. income ,or purPotet

GO