Lockary v. Kayfetz Appendix

Public Court Documents

June 15, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Lockary v. Kayfetz Appendix, 1988. f85e4971-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/57270879-ca88-4233-b6d4-7bb1830581a3/lockary-v-kayfetz-appendix. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

0-1

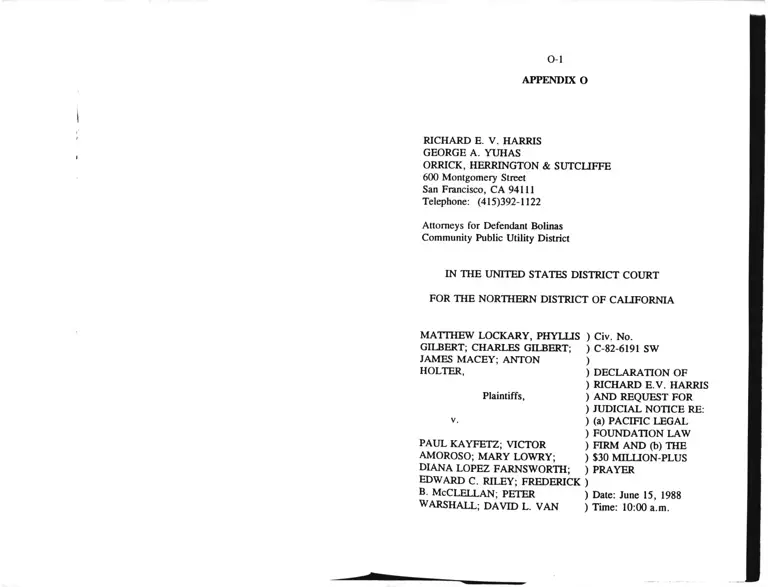

APPENDIX O

RICHARD E. V. HARRIS

GEORGE A. YUHAS

ORRICK, HERRINGTON & SUTCLIFFE

600 Montgomery Street

San Francisco, CA 94111

Telephone: (415)392-1122

Attorneys for Defendant Bolinas

Community Public Utility District

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

MATTHEW LOCKARY, PHYLLIS

GILBERT; CHARLES GILBERT;

JAMES MACEY; ANTON

HOLTER,

Plaintiffs,

v.

PAUL KAYFETZ; VICTOR

AMOROSO; MARY LOWRY;

DIANA LOPEZ FARNSWORTH;

EDWARD C. RILEY; FREDERICK

B. McCLELLAN; PETER

WARSHALL; DAVID L. VAN

) Civ. No.

) C-82-6191 SW

)

) DECLARATION OF

) RICHARD E.V. HARRIS

) AND REQUEST FOR

) JUDICIAL NOTICE RE:

) (a) PACIFIC LEGAL

) FOUNDATION LAW

) FIRM AND (b) THE

) $30 MILLION-PLUS

) PRAYER

)

) Date: June 15, 1988

) Time: 10:00 a.m.

0-2

DUSEN; DORIS ELAINE )

LeMIEUX; JACK BOWEN )

McCl e l l a n ; j . m ic h a e l )

GROSHONG; WILUAM NIMAN; )

JUDITH WESTON, as individuals; )

BOUNAS COMMUNITY PUBUC )

UTILITY DISTRICT, an )

incorporated public utility district; )

BOUNAS PLANNING COUNCIL, )

a non-profit corporation; JOHN )

GOODCHILD; GREGORY C. )

HEWLETT; STEVE MATSON; )

PATRICIA L. SMITH; RAY )

MORITZ; ROBERT J. SCAROLA; )

DIANE MIDDLETON McQUAID; )

FREDERICK G. STYLES, as )

individuals; and the MARIN )

COUNTY PLANNING )

DEPARTMENT, )

)

Defendants. )

)

DECLARATION

I, Richard E.V. Harris, do hereby declare that:

1. I am a member of the Bar of the State of

California, a member of the bar of this court, and a member

of the law firm of Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe, attorneys

for defendant Bolinas Public Utility District ("BCPUD")

herein.

0-3

(a) PLF LAW FIRM

2. I have read the separate opposition papers filed on

behalf of the Pacific Legal Foundation, which I found rather

curious. Throughout the separate opposition filed by the

Pacific Legal Foundation, it refers to itself variously as (i) "a

California nonprofit corporation qualified under Internal

Revenue Service Rules to receive tax-deductible donations,"

(ii) "not a party in this case", (iii) "a charitable corporation",

(iv) 'a nonparty corporation", (v) "a nonparty-nonattomey

corporation”, and (vi) "neither a party to this case nor an

attorney admitted to practice before this Court."

3. Nowhere in the papers does the Pacific Legal

Foundation refer to itself as it, and its attorneys, normally

describe it - a "law firm" or, more particularly, a "public

interest law firm." This declaration provides some

illustrations. (Unless otherwise indicated, the emphasis in

quotations in this declaration has been supplied.) Defendant

BCPUD requests judicial notice of the particular references

identified. The exhibits (attached hereto and those attached

to the Harris Declaration filed February 16, 1988) are

provided in further support of that request.

4. The Pacific Legal Foundation has represented

itself to be a law firm which participates in litigation "as

counsel" and which exercises "quality control." For

example, the Pacific Legal Foundation’s "Tenth Annual

Report 1973-1983" the first page of text includes the

following:

It was to evolve into the Pacific Legal

Foundation, the largest nonprofit public

interest law firm of its kind . . . . PLF’s case

selection . . . . PLF participates in cases

nationwide as plaintiff, as counsel and as

0-4

"friend of the court. . . . insured quality

control . . . .

Harris Decl. filed February 16, 1988, Exh. I.)

) 5. The Pacific Legal Foundation has represented

itself to the Internal Revenue Service and to the Attorney

Gerteral of California as a "Public Interest Law Firm.6 * * * * 11 A

copy of the Pacific Legal Foundation’s Periodic Report to

Attorney General of California for the year March 1, 1982

through February 28, 1983 which expressly incorporates the

IRS Form 990, Return of Organization Exempt from Income

Tax, for the same period, is attached as Exhibit G to the

Harris Declaration filed February 16, 1988. See IRS Form

4562 where the business or activity of the Pacific Legal

Foundation is expressly stated to be "Public Interest Law

Firm." Attached hereto as Exhibit A is a true and accurate

copy (provided by the State of California at my request) of

the Pacific Legal Foundation’s Periodic Report to Attorney

General of California for the period March 1, 1983 through

February 29, 1984 (when the amended complaint was filed

herein), also expressly incorporating IRS Form 990 which

also includes IRS Form 4562 expressly identifying the

business or activity of the Pacific Legal Foundation as

"PUBLIC INTEREST LAW FIRM."

6. Ronald A. Zumbrun (the senior PLF attorney,

whose name is on all or virtually all papers filed in this case

by the PLF) refers to the Pacific Legal Foundation as a "law

firm" and also refers to someone represented as a "Pacific

Legal Foundation client". For example, the May 13, 1985

issue of The Recorder (at page 4) contains a "viewpoint"

article by Ronald A. Zumbrun entitled "Pacific Legal

Foundation Reviews Critical Property Rights Cases”.

Identified as "one of a series of articles by Ronald A.

Zumbrun, President of the Pacific Legal Foundation," the

0-5

text of the article begins by stating that, when the Pacific

Legal Foundation was formed in Sacramento in 1973,

it became the first nonprofit public interest

law firm which litigated in support of the free

enterprise system . . . .

Halfway through the article, Mr. Zumbrun turns to a Coastal

Commission matter in this way:

Ponder the plight of another Pacific

Legal Foundation client. Viktoria Consiglio.

7. On the next day, May 14, 1985, The Recorder (at

page 2) contained another viewpoint article by Ronald A.

Zumbrun, who is identified as "President of the Pacific Legal

Foundation, a Sacramento-based public interest law firm that

litigates in support of limited government . . . . ” This

viewpoint article includes references to the Gilberts’ claim

against BCPUD, including the following:

If the Gilberts prevail, they will he entitled to

damages against the members of the hoard of

directors of the water of district who, under

the Civil Rights Act, would be personally

liable to those individuals whom they have

intentionally damaged. If successful, this

lawsuit will have precedential value nationally

and could single-handedly reverse the

confiscatory trends in the area of land use

regulation.

This Zumbrun viewpoint article is entitled "Pacific Law

oundation’s Involvement in Limiting Reach of

ovemment." Attached hereto as Exhibit B are true and

accurate copies of these articles from the May 13 and 14,

0-6

1985 issues of The Recorder.

8. The March, 1983 issue of Pacific Legal

lfoundation’s The Reporter contains a "President’s Message"

column by Ronald A. Zumbrun which is entitled "Just

Compensation: The Case We’ve Been Waiting For.” In it,

tyis references to the Bolinas litigation include:

PLF has filed suit against the district in

federal court, thus circumventing the

California courts, which have been decidedly

reluctant to clarify the just compensation issue

in other PLF cases. We are seeking

substantial personal damages from the water

district board members, putting all government

entities on notice that we are going to the mat

with this one.

On the first page of that same issue of the The Reporter,

there is another article referring to this litigation entitled

"PLF Files Major Water Rights Case." (Mr. Zumbrun’s

column expressly references that article.) The article

includes the following references:

One of the most significant PLF lawsuits in

recent years was filed late last year in San

Francisco federal court . . . .

PLF filed suit on behalf of five property

owners in Bolinas . . . .

By filing this suit in federal court, PLF hopes

to stem this frightening practice from moving

nationwide.

***

0-7

As in many land use cases brought hv

PLF. . . . .

The PLF suit alleges that water district

policies violate the Fifth Amendment

g u a r a n t e e o f p a y m e n t o f j u s t

compensation, . . . . This case will be an

extremely important one for PLF. . . . .

Attached hereto as Exhibit C is another copy of the above

stories from Pacific Legal Foundation’s March 1983 issue of

The Reporter.

9. The Pacific Legal Foundation’s literature soliciting

contributions also describes the PLF as a "law firm." For

example, the first page of a December 22, 1982 solicitation

letter (sent shortly after this case was filed) contains the

following:

Pacific Legal Foundation is an independent

nationwide public interest law firm defending

individual freedom, private property rights,

and the free enterprise system. PLF is

successfully confronting governmental

bureaucracies, environmental extremists,

welfare rights organizations, and other special

interest groups.

Later, the solicitation letter states:

Today, PLF is handling more than 100 legal

proceedings across the United States. Your

financial assistance will make it possible to

carry this burden to conclusion.

Attached hereto as Exhibit D is a true and accurate copy of

0-8

the PLF’s December 22, 1982 solicitation letter.

10. At the beginning of the PLF’s separate opposition

papers, there appears this sentence:

' Pacific Legal Foundation has not signed a

"pleading, motion, or other paper" to be filed

in this court.

The statement was apparently made in an effort to dispel any

idea that the Pacific Legal Foundation really has had anything

to do with this litigation. While I have not reviewed all the

files, a quick beginning revealed the following examples

where papers were expressly signed on behalf of the Pacific

Legal Foundation:

PACIFIC LEGAL FOUNDATION

By: /signed/_________

DARLENE E. RUIZ

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

MATTHEW LOCKARY; PHYLLIS GILBERT;

CHARLES GILBERT; JAMES MACEY;

ANTON HOLTER

(See Docket No. 5)

Pacific Legal Foundation

by /signed/______

Darlene Ruiz

Attorney for Plaintiffs

(See Docket No. 6)

0-9

Pacific Legal Foundation

by __ /signed/_______

Darlene Ruiz

Attorney for Plaintiffs

(See Docket No. 9)

PACIFIC LEGAL FOUNDATION

By __ /signed/_______

DARLENE E. RUIZ

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

(See Docket No. 15)

PACIFIC LEGAL FOUNDATION

By __ /signed/______

Darlene E. Ruiz

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

(See Docket No. 17)

PACIFIC LEGAL FOUNDATION

By /signed/______

DARLENE E. RUIZ

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

(See Docket No. 18)

0-10

11. Of course, the Pacific Legal Foundation’s logo,

name, address and telephone number were already preprinted

on the thousands of pages of papers filed in this action by the

PLF attorneys. (See, e.g. Complaint, Docket No. 1 and

Amended Complaint, Docket No. 112.) Other PLF use of

the law firm logo includes the following example from the

PLF’s "Tenth Annual Report 1973-1983:"

I

[INSERT LOGO]

(See Harris Deck filed February 16, 1988, Exh. I, last page.)

In addition, the PLF attorneys’ correspondence with the court

regarding this litigation, as well as correspondence with

opposing counsel and others, has been on Pacific Legal

Foundation letterhead.

(b) THE $30 MILLION -PLUS PRAYER

12. The plaintiffs sought enormous damages from,

among others, BCPUD and the individual defendants.

Plaintiff s opposition papers inaccurately suggest that "the

$30 million prayer for damages and the terrifying effect of

such a prayer" "was laid to rest nine months after the filing

of the Complaint." (Opposition, p. 2: 10-16.) The

opposition papers also suggest that the cloud over BCPUD’s

finances "could only exist, if at all, for about nine months the

time between the original Complaint, filed November 10,

1982, and the Amended Complaint, and that after the

O-ll

° f the claims, "any cloud existing in

BCPUD s imagination surely should have evaporated since

the basis for trebling damages was gone." (Id., p. 56: 6-15.)

13. The original Complaint’s prayer had numerous

references to damages, including the following:

WHEREFORE, plaintiffs pray for judgment

against defendants as follows:

1. Damages for violation of plaintiffs’ civil

rights in the amount of $10 million.

***

4. Judgments for three times the amnnn| of

actual damages for violation of Sections 1 and

2 of the Sherman Act which plaintiffs a lh y .

are in excess of $10 million to be trebled as

provided by law.

7. Interim damages for a temporary

taking . . . .

8 Id the alternative and cumulatively as

appropriate to plaintiffs’ prayer for

declaratory, injunctive, and interim damage

relief prayed for hereinabove, plaintiffs pray

for judgment against defendants as follows:

a damages for the fpir market vain*

Sf-the property in an amount not

presently precisely ascertainable but

EQUess than $10 mill;™ A more

0-12

precise amount of damages will be

proven and prayed for at time of trial;

b. Interim damages for a temporary

taking in an amount not yet precisely

ascertainable.

12. Other consequential damages flowing

directly from defendants’ course of conduct

herein described which plaintiffs may have

suffered but not discovered or which they may

hereafter suffer.

***

14. Although the Amended Complaint may have

dropped the express dollar amounts, nothing alleged that

plaintiffs had changed their position regarding fair market

values, the magnitude of actual damages, or the expansive

damages sought. Indeed, the Amended Complaint filed

August 3, 1983, increased the number of plaintiffs, the

number of defendants, and the number of "claims." There

was no reduction in the amount of property allegedly "taken”

(which plaintiffs alleged in the original Complaint had a "fair

market value . . . not less than $10 million"). Both

complaints sought a determination and trebling of the actual

damages resulting from the alleged antitrust violations (which

the plaintiffs alleged in the original Complaint were "in

excess of $10 million"). Additionally, the prayers in both

complaints continued to seek civil rights damages, interim

damages, attorneys’ fees, litigation costs, and other monetary

items, including "(ojther consequential damages flowing from

the defendants’ course of conduct . . . which plaintiffs may

have suffered but not discovered or which they may hereafter

0-13

suffer."

15. When the Amended Complaint was filed, there

was no formal or informal statement by plaintiffs or plaintiffs

counsel that the Amended Complaint sought ]gss in damages

than was sought in the original Complaint. Although the

prayers in both complaints state that damages for the fair

market value of the property allegedly taken would be proven

and prayed for at the rime of trial, I can find nothing in the

Amended Complaint which, for example, backs off the

allegation of the original Complaint that the fair market value

of the property taken is "not less than $10 million.’’

16. In April 1984, other defense counsel and I met

with plaintiffs’ counsel to discuss various matters relating to

discovery. Following up on oral requests made at that

meeting, I wrote plaintiffs’ counsel on April 23, 1984

requesting, among other things, their contentions as to the

amount of damages each plaintiff was seeking plus the basis

for the claimed damages. A true and accurate copy of my

letter of April 23, 1984 is attached hereto as Exhibit E. The

information was not provided, despite repeated requests, both

oral and written. Attached hereto as Exhibit F is a copy of

my letter dated May 9, 1985 to plaintiffs’ counsel, which

contains another written request for the damages contention

information. The requested information regarding the

damages amounts (and bases) was never provided.

17. As recently as the Ninth Circuit prebriefing

conference, which was held on March 28, 1988 plaintiffs’

counsel informed me and other defense counsel that plaintiffs

were not willing to eliminate any claims against any

defendants from their appeal. Plaintiffs’ suggestion that the

em ymg effect” of their damages claims "was laid to rest”

0-14

in August 1983 is, I believe, inconsistent with the record in

this litigation.

| Executed this 1st day of June, 1988 at San Francisco,

California.t

i I declare under penalty of peijury that the foregoing

is true and correct.

Richard E. V. Harris

P-1

APPENDIX P

RICHARD E. V. HARRIS

GEORGE A. YUHAS

ORRICK, HERRINGTON & SUTCLIFFE

600 Montgomery Street

San Francisco, California 94111

Telephone: (415)392-1122

Attorneys for Defendant Bolinas

Community Public Utility District

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

MATTHEW LOCKARY;

SUSAN IRLAND

LOCKARY;

PHYLLIS GILBERT;

CHARLES GILBERT;

JAMES MACEY;

ANTON HOLTER; MESA

RANCH INC., a

California limited

partnership,

Plaintiffs,

)

)

)

)

)Civ.No. C-82-6191SW/WDB

)

) SUPPLEMENTAL

DECLARATION

)OF RICHARD E.V.

)HARRIS RE: (a) PLF’S

)STATUS, AND (b)

SANCTIONS PAID BY

)PLF IN CONNECTION

)WITH 1983 PUBLIC

\

P-2

V .

BOLlNAS COMMUNITY

PUBLIC UTILITY

DISTRICT; PAUL

KAYFETZ;

VICTOR AMOROSO;

MARY LOWRY;

DIANA LOPEZ

FARNSWORTH;

C. RILEY; PETER

WARSHALL; DORIS

ELAINE LeMIEUX;

JACK BOWEN

McCl e l l a n ,

J. MICHAEL GROSHONG,

WILLIAM NIMAN;

ORVILLE SCHELL;

MARGUERITTE HARRIS;

JUDITH WESTON;

BOLINAS COMMUNITY

PUBLIC UTILITY

DISTRICT, an

incorporated public

utility district;

BOUNAS PLANNING

COUNCIL, a non-profit

corporation; JOHN

GOODCHILD; GREGORY

C. HEWLETT; STEVE

MATSON; PATRICIA L.

SMITH; RAY

MORITZ; ROBERT J.

SCAROLA; DIANE

MIDDLETON McQUAID;

)RECORDS ACT

)LITIGATION

)AGAINST BCPUD AND

^SUBSEQUENT APPEAL

)

)

)Status Conference

)

)Date: March 14, 1989

)Time: 10:00 a.m.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

P-3

FREDERICK G. STYLES; )

and the COUNTY OF )

MARIN, )

)

Defendants. )

___ )

I, Richard E.V. Harris, do hereby declare as

follows:

1. I am a partner with the law firm of Orrick,

Herrington & Sutcliffe and one of the attorneys for defendant

Bolinas Community Public Utility District ("BCPUD"). If

called as a witness, I could testify to the following of my

own personal knowledge.

A. PLF’S STATUS

2. This portion of this declaration supplements the

DECLARATION OF RICHARD E.V. HARRIS AND

REQUEST FOR JUDICIAL NOTICE RE: (a) PACIFIC

LEGAL FOUNDATION LAW FIRM AND (b) THE $30

MILLION-PLUS PRAYER, filed June 1, 1988, and made

pan of BCPUD’s APPENDIX filed January 6, 1989, at Tab

No. 9. In paragraphs numbered 2-11, and the exhibits

thereto, I referred to various Pacific Legal Foundation

CPLF") statements that it was a "law firm," that it

participated in cases "as counsel," and that a person

represented was a "Pacific Legal Foundation client. " In

P^graph 10, I also referred to specific instances in this

Court’s files where papers were expressly signed on behalf

of the Pacific Legal Foundation.

F to its recent "RESPONSE OF PACIFIC LEGAL

UNDATION TO THE MOTION FOR SANCTIONS," the

P-4

PLF states on page 1 that "PLF is neither a party to this case

nor an attorney for a party." On page 4 the PLF states that

"BCPUD requests sanctions against ’plaintiffs and their

attorneys’ — a group that does not include Pacific Legal

Foyndation within its membership.” And, on page 6, the

PLF states that ’’PLF was not ’plaintiffs’ counsel’ in this

action, . .

4. The recent statements by the PLF in its response

to the motion for sanctions seemed to me to be at odds with

not only the PLF’s statements in its own publications and the

record referred to above, but also with PLF correspondence

with BCPUD after this case had been pending for

approximately one year. In a letter to BCPUD s general

manager from PLF attorney James I. Collins on Pacific Legal

Foundation letterhead, Mr. Collins stated:

PLF is the attorney for plaintiffs in Lockary; it

is not a party.

Attached hereto as Exhibit A is a true and accurate copy of

the November 2, 1983 letter from PLF attorney Collins to

BCPUD General Manager Buchanan, which copy is attached

to a Declaration of Phil Buchanan in Wolfs v. Bolin_as

Community Puhlic Utility District (Marin County Superior

Court No. 115257).

B. SANCTIONS PAID BY PLF

5. In its response to the motion for sanctions and

attorneys fees herein, the PLF apparently is attempting to

distance itself from the state court decisions in Wolfe v.

Rolinas Community Public Utility District by stating that "no

sanctions were expressly levied against PLF." (Emphasis

original.) A true and accurate copy of the Marin County

P-5

Superior Court’s January 19, 1984, Order is in BCPUD s

Appendix filed January 6, 1989 at Tab No. 8, Exhibit E. It

states, in part:

Respondent would be entitled to attorneys fees if

the Court finds that the "plaintiffs case is clearly

frivolous . . . "

It would appear that petitioner

brought this action to harass respondent district.

Petitioner is represented by Pacific Legal

Foundation as is the plaintiff in the federal

action. It appeared that the disclosures plaintiff

sought in this action were to be used in

prosecuting the federal action. A review of

events leading to the filing of this action

convinces this Court that this action was brought

for an improper motive. Therefore, respondent

is entitled to reasonable attorneys fees and costs.

A reasonable fee for such services is $1,360.00

plus court costs of $14.50. Respondent shall

have judgment against petitioner for said sums.

6. The Marin Court Superior Court’s decision was

affirmed by the Court of Appeal for the First Appellate

District. A true and accurate copy of that appellate decision

can be found in BCPUD’s Appendix at Tab No. 8, Exhibit F.

In a unanimous decision, the court stated, in part:

Appellant argues that the judgment

must be reversed because . . . and (3) the action

was brought in good faith. We disagree with

each of these contentions.

On September 30, 1983,

P 6

appellant, through his attorneys, the Pacific

Legal Foundation, contacted respondent. He

requested that he be permitted to inspect, as the

trial court put it, ’virtually all of [respondent’s]

records. ’

Finally, appellant disputes the trial

court’s finding that he brought the action for an

improper motive and meant ’to harass respondent

district.’ Considering the sheer volume of

documents which appellant designated, his

demands of immediate compliance with these

extensive requests; his insistence on filing suit in

spite of respondent’s keeping him constantly

informed of its progress; and his going forward

with the December 9 hearing even though

respondent had already made the records

available to his satisfaction, the trial court’s

determination was reasonable and well supported

by the evidence. Respondent was properly

awarded costs and attorneys fees. (Emphasis in

original)

7. Although the recent PLF response states that "no

sanctions were expressly levied against PLF," it does not

state that the sanctions were not, in fact, paid by the PLF.

As outlined below, the PLF, not Wolfe, apparently did pay

the sanctions/attomey fees resulting from the two state court

decisions in Wolfe.

P-7

8. With respect to request for BCPUD’s documents,

the formal application signed by PLF attorney lists the

"Pacific Legal Foundation" as the "applicant," not Wolfe or

anyone else. A true and accurate copy of the BCPUD form

signed by the PLF attorney is attached hereto as Exhibit B.

9. The bad faith and harassment findings having

been affirmed along with the Government Code Section 6259

attorneys fee award, BCPUD sought additional fees and costs

of $4,708.80 under that Government Code Section in a state

court filing on July 21, 1986.

10. I was informed shortly after September 5, 1986

that the $4,708.80 was paid by a Pacific Legal Foundation

check, numbered 2602, dated 8-25-86, drawn on a PLF

account at the Great American Federal Savings and Loan

Association in Sacramento, California, sent to BCPUD’s

attorney in Wolfe. Attached hereto as Exhibit C is a true and

accurate copy of the cover letter I received together with a

copy of the PLF check. I have subsequently been informed

that the remainder of the $6,274.25 (the $1,274.50 awarded

by the trial court in 1984 and $190.90 interest) were paid

using Great American cashier’s checks, dated 7-10-86 and

7-17-86, which were also sent by the PLF to BCPUD’s

attorney in Wolfe.

Executed this 6th day of March, 1989, in the City

and County of San Francisco.

I declare under penalty of peijury that the

foregoing is true and correct.

Richard E. V. Harris

I

Q-i

APPENDIX Q

RICHARD E. V. HARRIS

GEORGE A. YUHAS

ORRICK, HERRINGTON & SUTCLIFFE

Old Federal Reserve Bank Building

400 Sansome Street

San Francisco, California 94111

Telephone: (415)392-1122

Attorneys for Defendant Bolinas

Community Public Utility District

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

MATTHEW LOCKARY, ) Civ. No.

SUSAN IRLAND LOCKARY; ) C-82-6191 SW/WDB

PHYLIJS GILBERT; CHARLES)

GILBERT; JAMES MACEY;

ANTON HOLTER: MESA

RANCH INC., a California

limited partnership,

Plaintiffs,

v.

PAUL KAYFETZ, VICTOR

AMOROSO; MARY LOWRY

) DECLARATION OF

) RICHARD E. V.

) HARRIS IN

) FURTHER SUPPORT

) OF BCPUD’S

) APPLICATION FOR

) SANCTIONS/FEES

) [STAGE II

) PROCEEDINGS]

)

1

Q-2

DIANA LOPEZ )

FARNSWORTH; EDWARD C. )

RILEY; PETER WARSHALL; )

DpRIS ELAINE LeMIEUX; )

JACK BOWEN McCLELLAN; )

J. MICHAEL GROSHONG; )

VfILUAM NIMAN; ORVILLE )

SCHELL; MARGUERITTE )

HARRIS; JUDITH WESTON; )

BOLIN AS COMMUNITY )

PUBLIC UTILITY DISTRICT, )

an incorporated public utility )

district; BOLINAS PLANNING )

COUNCIL, a non-profit )

corporation; JOHN )

GOODCHILD; GREGORY C. )

HEWLETT; STEVE )

MATSON;PATRICIA L. )

SMITH; RAY MORITZ; )

ROBERT J. SCAROLA, DIANE )

MIDDLETON McQUAID; )

FREDERICK G. STYLES; and )

the COUNTY OF MARIN, )

)

Defendants. )

)

I, Richard E.V. Harris, do hereby declare as follows:

1. I am a member of the Bar of the State of

California and member of the Bar of this Court. I am also

a member of the law firm of Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe,

attorneys for defendant Bolinas Community Public Utility

District ("BCPUD") in this action. If called as a witness, I

could testify to the following of my own personal knowledge.

Q-3

PLF OPERATIONS:

FINANCIAL RESOURCES

2. According to the IRS Form 990’s filed by the

Pacific Legal Foundation ("PLF") with its Periodic Reports

to the Attorney General of California, the PLF’s annual

revenues have been substantial during each of the years that

the Lockarv case has been pending. Total PLF revenues (by

fiscal year) are shown on those reports as follows:

PLF

Fiscal PFL Revenues Per

Year___________________IRS Form 99Q

1982- 1983

1983- 1984

1984- 1985

1985- 1986

1986- 1987

1987- 1988

1988- 1989

1989- 1990

$2,559,274

2,446,651

2,481,839

2,265,076

2,405,115

2,905,457

4,217,701

5,835,885

From 1982-83, when Lockarv was filed, through February

1990, the PLF’s total revenues, as shown on these reports,

were $25,116,998. True and accurate copies of excerpts

from the IRS 990’s filed as part of those reports are attached

as Exhibit A.

3. The PLF publishes In Perspective, a

newsletter. The Winter 1989 issue contained the PLF’s

description of one of its fundraising activities. Entitled "PLF

Fundraising Event Brings Private Property Advocates

Together," the PLF description contained the following:

More than 250 members of the nation’s

Q-4

real estate development community gathered in

Sacramento on November 2 for a special

fundraising tribute to PLF’s activities in the

| land use and private property arena.

• ' * * */

1 Following Zuntbrun, Raymond Watt,

chairman of Watt Industries in Los Angeles

and a member of the Host Committee,

expressed his thanks to the Foundation and

asked everyone present to carry the PLF

fundraising flag.

"If every PLF supporter would call just

one other potential supporter, we could take

care of PLF’s funding needs overnight." he

said.

Attached as Exhibit B is a true and accurate copy of the page

from the Winter 1989 issue of the PLF’s In Perspective.

PLF OPERATIONS:

LITIGATION LAW FIRM STATUS, LITIGATION

AND TRAINING FUNCTIONS

4. Additional information regarding the PLF and

its operations is provided below. Most of the information

comes directly from the PLF’s own publications; that

information is provided first.

5. According to its annual reports, the PLF

claims a very close relationship to the litigation process and

the courts. The annual reports indicate that the PLF is not

merely a law firm but that it is a litigation law firm. At least

one report says that the PLF regards "the courtroom" as its

Q-5

"forum." Another says that the PLF’s "main function is

litigation."

6. Excerpts from some annual reports and other

PLF publications are identified and highlighted below. (The

emphasis in quotations below has been supplied unless

otherwise indicated.) True and accurate copies of the

referenced pages from those annual reports are attached

hereto as Exhibits C through J.

7. The PLF’s first annual report, "Pacific Legal

Foundation, The First Report: A Record of Achievement,

Winter 1973-74” began with a "Message From the

Chairman" on the inside cover which said:

The Pacific Legal Foundation, a

non-profit public interest law firm, was

established to correct an imbalance in the

presentation of issues in litigation that involves

major public policy.

m m m

Although it has been operating less

than one year, the Foundation has won several

important victories and is involved in scores of

legal cases . . . . It is protecting your

interests, assisting the courts, and performing

a vital public service by presenting "the other

side" on issues of major public interest.

8. The chairman’s message in that same annual

report was followed with a "Statement of Purpose" which

said, among other things:

Q-6

The Foundation has received wide

support . . . . The legal activities of the

Foundation will be guided by these principal

| policies, adopted by the Board of Trustees:

1. The Foundation shall represent

, California citizens, individual or corporate,

and citizens of the United States, on matters of

public interest at all levels of the

administrative and judicial process.

2. The Foundation shall insure that

all interests are fully and properly represented

in court on issues affecting the public and

private sectors.

4. The Foundation shall not derive

any Financial benefit from the legal services it

provides.

10. A Board of Trustees shall be

appointed, consisting of not less than 16 nor

more than 19 members, of which a majority

shall be members in good standing of the State

Bar of California.

9. The "Report of the Executive Vice President-

Administrator" in the PLF "Third Annual Report, 1975"

expressly identified the central nature of litigation:

Because we recognize that the Foundation’s

main function is litigation, the vast majority of

our funds are directed to legal activities.

Q-7

10. The PLF’s "Fourth Annual Report begins by

asserting on page one that "the courtroom" is the PLF’s

forum:

Pacific Legal Foundation

Our client: The taxpayer

Our Forum: The courtroom

* * *

Reason and responsibility are our arguments.

The courtroom is our forum.

* + +

Our purpose is to present to the courts . . . .

* * *

Since its founding in 1973, the Foundation has

been actively involved in more than 100 legal

proceedings . . . .

* + m

Pacific Legal Foundation is governed by a

board of prominent citizens, the majority

attorneys . . . .

Ronald Zumbrun’s "President Message" on the third page

continues the theme, stating among other things:

During the past fiscal year, the

Foundation handled more litigation than the

total for its first three years combined.

Q-8

The Foundation will continue to be

| highly selective in choosing litigation in which

to enter.

/

, 11. The PLF’s "Fifth Annual Report” continued

the litigation theme, introducing the PLF on page one with

such comments as:

Since its founding, [PLF] has been

actively involved in more than 150 legal

proceedings, winning 80 percent of those

which have reached final decision.

It . . . has litigating offices in Sacramento,

California, and Washington, D.C., a liaison

office in Seattle, Washington, and a project

office in San Diego, California.

The PLF record of legal victories is

impressive by any standard — proof of the

impact possible when aggressive, independent

and dedicated professionals speak rationally

for the broad public interest.

Ronald Zumbrun’s "President’s Message" on page three

continues the litigation law firm theme:

. . . for Pacific Legal Foundation

handled and won more cases than in any past

year.

* * *

Q-9

As the pioneer of law firms advocating the

broad public interest of working men and

women in business, agriculture and industry,

PLF remains the model to be followed in this

field.

PLF’s winning team of attorneys is supported

by an exceptional legal and administrative

staff . . . backed by an outstanding Board of

Trustees.

We select cases which deal with key

precedent-setting issues. Every case is a test

case.

The same annual report describes PLF activities using such

phrases as "PLF successfully defended a lawsuit . . . [p. 9],

"Pacific Legal Foundation successfully represented individual

employees 11], "frlepresenting various builders and

contractors, PLF challenged a federal law . . . " [id.], and

"Pacific Legal Foundation is involved in numerous suits

challenging . . . [id.].

12. The PLF’s "Sixth Annual Report, 1978-1979"

introduces the PLF on page one with such comments as:

PLF brings the viewpoint of this segment of

the public before the courts.

In the beginning, PLF’s litigation

focused on issues that surfaced in the Pacific

region.

* * *

Q 12

Years," that PLF annual report contains the already noted,

succinct summary statement: "PLF participates in cases

nationwide, as plaintiff, as counsel and as ’friend of the

co|irt.’"

; 17. The PLF’s annual reports are but one of the

PLF publications describing the PLF’s litigation activities in

this manner. Similar descriptions have continued right

through the pendency of BCPUD’s sanctions/fees motion.

The Autumn 1989 issue of the PLF’s In Perspective, page

two, contained a "President’s Message" by Ronald A.

Zumbrun which began as follows:

There are a number of different ways

that the PLF pursues its litigation efforts. We

can file a legal action on behalf of a private

individual . . ., we can represent a party by

intervening in an ongoing lawsuit . . or

. . . we can file an amicus curiae or "friend

of the court" brief.

The President’s message, which was entitled "Why Amicus

Curiae Briefs are Important," also included the following

comments:

When you think of the many thousands

of lawsuits filed each day, . . . you realize

that the PLF could not possibly represent

parties in all but a small fraction of the cases

that could impact on you legal rights.

We will continue to represent parties in

bringing, defending, and intervening in

lawsuits.

Q-13

A true and accurate copy of page two of the Autumn 1989

issue of the PLF’s In Perspective is attached as Exhibit K.

18. Both prior to and during the course of the

Lockarv action, the PLF has also suggested that it has a role

in training attorneys. For example, in its "Sixth Annual

Report" in "A Message from the President and Chairman of

the Board” on page three, the report refers to a fellowship

program where law school graduates "will be given training

and experience in public interest litigation bv PLF staff

attorneys. ” On page eleven of the same report, there is

another reference to "education and training under the direct

supervision of PLF senior trial attorneys." The report

continues: "The purpose of the program is to train the future

leaders of the legal profession in the new and expanding field

of public interest law." See Exhibit G.

19. In the November 1981 issue of the California

Lawyer, roughly one year before this action was filed, the

description of the PLF’s activities included the following

attributed to Robert Best, one of the PLF attorneys in this

action:

Once it enters a case, PLF stays no

matter how costly, says Best. "While we

rarely get into a war of attrition, government

opponents have tried to play that with us. But

they’ve never won. We won’t back off. We

go an eye for an eye -- it’s part of our

reputation," he says.

A true and accurate copy of the article from the November

1981 California Lawyer is attached hereto as Exhibit L.

Executed th is__day of July, 1990, in the City and

County of San Francisco.

Today, PLF litigates from coast to coast . . . .

Q 10

PLF litigates in all areas of the public

{ interest . . . .

"X Message from the President and Chairman of the Board"

on page three of the same annual report continues with

references to "a PLF suit," "[t]he Foundation is litigating,"

"[t]hree PLF actions," "in two cases before the Ninth Circuit

Court of Appeals, PLF argued," "PLF has filed suit," and

"PLF has an ambitious litigation program for the coming

year." The same annual report contains such references to

PLF activities as "PLF represented the supervisors suing

HEW . . . " [p. 7] and "PLF is assisting the plaintiff to

obtain a rehearing and has been asked to act as

co-counsel . . . " [p. 9].

13. The PLF’s "Seventh Annual Report,

1979-1980" introduces the PLF on page one by quoting from

the "policy concept" adopted by the first Board of Trustees

and referring to itself as a "law firm." On page three,

"Looking Ahead," signed by Ronald Zumbrun begins: "PLF

is a public interest law firm . . . " In the annual report,

descriptions of PLF’s activities include "frlepresenting the

city of Chula Vista, PLF is also challenging the commission’s

authority . . . " [p. 8],

14. The PLF’s "Eighth Annual Report, 1980-1981”

has a "Year in Review" on page one which begins:

Q l i

In its eighth year of litigating in the public

interest, [PLF] participated in more than 100

cases from coast to coast.

In New York, PLF represented construction workers . . . ."

Other references to PLF activities in the annual report

included ”[i]n Alaska PLF brought suit . . . [p. 1], "[i]n

an unrelated action, PLF helped defend . . . ." [id.], "PLF

represented San Francisco’s controller, who was sued by the

city . . . " [id.], a list limited to "only litigation in which

PLF actively participated," [p. 4], "PLF has litigated case

after case . . . " [p. 8], "ELF agreed to represent them . . .

" [id ], "Jacobs . . . asked PLF to represent him" [p. 10],

and "PLF represented him and his office in the successful

suit argued before the court of appeal" [p. 12].

15. The PLF’s "Ninth Annual Report, 1981-1982”

contains a list on page three of "litigation in which PLF

actively participated in 1981-82” identifying eighty cases.

Elsewhere descriptions of the PLF’s activities include "[i]n

a similar case, PLF represented 13 farmworkers who were

fired . . . " [p. 6], "Justice Kaufman asked PLF to represent

him" [id.], "[i]n San Francisco, PLF is defending the city

controller who is being sued . . . " [id-], and "frlepresenting

the California Grange and individual owners of small farms,

PLF has intervened in the case . . . " [id.].

16. These foregoing excerpts reflect the

self-described role of the PLF and its relationship to litigation

and the to courts during the nine years of PLF activities

immediately prior to the filing of this action. The PLF’s

Tenth Annual Report", issued during the year in which this

action was filed, was reviewed in an earlier declaration,

which appears at Tab 8, Exhibit I, Appendix With Selected

Materials. On page one, under the heading "The First 10

i

Q 14

I declare under penalty of perjury that the foregoing

is true and correct.

Richard E. V. Harris

I

R-l

APPENDIX R

ENDORSED

FILE

Nov 22 1991

RENE C. DAVIDSON, County Clerk

By: /»/ Lillian C. Don

Lillian C. Don, Deputy

SUPERIOR COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA

IN AND FOR THE COUNTY OF ALAMEDA

CHARLES GILBERT; )

PHYLLIS GILBERT; )

MATTHEW LOCKARY; )

SUSAN IRLAND )

LOCKARY; and )

I AMES MACEY, )

) No. 636481-0

Petitioners and )

Plaintiffs, ) STATEMENT

vs. ) OF

) DECISION

R-2

STATE OF CAUFORNIA; )

DEPARTMENT OF )

HEALTH SERVICES; )

KENNETH KIZER, in )

his official capacity as )

Director )

of the Department of )

Hfealth Services; )

BOLIN AS COMMUNITY )

PUBLIC UTILITY )

DISTRICT; and )

DOES I through XX, )

)

Respondents and )

Defendants. )

)

* * *

Essentially, petitioners attack the validity of the Bolinas

moratorium on additional water hookups and the

administrative process by which petitioners were denied those

hookups.

For the reasons set forth below, the Court is

determined to deny both petitions.

* * %

HI. IS THERE A WATER SHORTAGE EMERGENCY?

Accordingly, the threshold issue in this case is

whether there is, in fact, a water shortage emergency. The

resolution of this issue will determine not only the validity of

the moratorium itself, but also will facilitate the resolution of

petitioners many other claims which are premised on the

R-3

assumption that the water emergency is a sham.

* * +

By way of expert testimony which challenges the

factual predicates for the moratorium, petitioners rely almost

exclusively on the testimony and declaration of Dietrich

Stroeh. Stroeh’s analysis is directed at the 1982 engineering

report of the Department of Health Services which was

prepared by Robert Hultquist. Although the DOHS report

was not relied on by the District in determining the propriety

of the moratorium, it does shed some light on the continuing

validity of the water shortage emergency and, thus, on the

continuing validity of the moratorium.

As the District points out, Stroeh’s disagreement with

the DOHS report is largely philosophical.

* * *

Even to the untutored eye, problems with Stroeh’s

analysis are apparent. First, as the District points out, Stroeh

"ignores the fact that [the District’s] summer time use is not

limited to water taken from Arroyo Honda. [The District]

also takes water from its supply of stored water." Thus,

"demand” is substantially understated.

* * *

Second, there is no evidence whatsoever that the years

from 1982 to 1986 represent a fair sampling for determining

long-range water policy. In fact, several of those years were

exceptionally "wet".

Third, the assertion that 39 acre-feet annually is

available from Arroyo Honda is without demonstrable

R-4

foundation.

In sum, the District had substantial expert evidence

available to them upon which to make a reasoned decision to

declare a water shortage emergency and to enact and

maintain a water hookup moratorium.

I * * *

In order to obtain the added benefit of objectivity and

the additional confidence that the Court has not been misled

by the testimony of an expert possibly more persuasive than

correct, the Court appointed a special master in accord with

Evidence Code section 730. The task of this court-appointed

expert was to evaluate the current conditions of the District’s

water system and to advise the Court as to whether the

current and projected water supply conditions in Bolinas

constitute a valid water shortage and, thus, justify the

continuance of the moratorium.

* * *

In light of this evidence, the Court finds that there is

a solid factual basis for declaring a water shortage emergency

and, thus, for imposing a moratorium which precludes

potential water users from tapping into the water supply

which is both fragile and limited. The Court cannot conclude

that the District acted in an arbitrary or capricious manner or

that their actions were entirely lacking in evidentiary support.

♦ * *

In this case, the bottom line is whether there is valid water

shortage emergency which justifies the moratorium.

Based upon the Administrative record, it seems

R-5

apparent that the moratorium has been justified from its

inception to the present based upon realistic concerns about

the capacity of the district’s water system to meet

conservative demands in times of continuing drought,

particularly given the marginal capacity not only of the

storage system, but the delivery system, as well.

n . WERE PETITIONERS AFFORDED A FAIR

HEARING?

* * *

The Administrative Record reflects the comprehensive

presentation permitted petitioners in the pursuit of their

petitions before the Board. There are numerous appearances,

the submission of hundreds of pages of evidence, the

opportunity to respond to the District’s evidence, and full

unencumbered representation by counsel. Apart from the

allegations of "inherent" and "personal" biases, petitioners

are bereft of any realistic argument that the hearings were

deficient in any way. As noted, petitioners’ assertions of

bias are without foundation in the record.

* * *

The petitions for peremptory and administrative writs

are denied.

Dated: November 22, 1991

LsL_________________

Richard A. Hodge,

Judge of the Superior Court

I

S-l

APPENDIX S

FILED

Apr 2 - 1990

RICHARD W. WIEKING

CLERK, U.S. DISTRICT

COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT

OF CALIFORNIA

SAN JOSE

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA

MATTHEW LOCKARY, )

et al., )

)

) C-82-6I91(SW)

Plaintiffs, )

) ORDER ADOPTING

v. ) FINDINGS OF

) MAGISTRATE BRAZIL

PAUL KAYFETZ, et al., )

Defendants. )

-- ---------------------------------- )

I have carefully reviewed the Report and

Recommendations by Magistrate Brazil acting as Special

master and filed on January 11, 1990, with respect to the

liability of plaintiffs’ attorneys for sanctions. I have also

read and considered the comments on that Report submitted

by the parties. I HEREBY ADOPT THE FINDINGS OF

S-2

FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW AND ACCEPT

THE RECOMMENDATIONS CONTAINED THE REPORT

BY MAGISTRATE BRAZIL. I Find that the circumstances

of this case clearly support the imposition of substantial

monetary sanctions on the Pacific Legal Foundation. In

addition, the Magistrate’s findings of fact and conclusions of

law clearly justify his issuing an order requiring attorneys

Darlene Ruiz, Ronald Zumbrun, Harold Hughes, Onin

Finch, and Robert Best, to show cause why they should not

be sanctioned in their individual capacities. However, I

concur with the comment made by Pacific Legal Foundation

in the objection filed January 29, 1990, that Ms. Ruiz may

not be held liable for attorneys’ fees under Rule 11 for

signing the Motion to Strike referred to on page 100 of the

Report, because that motion had been signed several months

before the effective date of amended Rule 11, and an award

of attorneys’ fees is not provided for the old Rule 11.

I hereby ORDER Magistrate Brazil to commence

further proceedings on the issue of the amount of the

sanctions to be imposed on the Pacific Legal Foundation, and

on the issue of the liability for the sanctions of the individual

attorneys noted in the Report. If the Magistrate concludes

that any attorney or attorneys should be sanctioned in their

individual capacities, he should also make findings and

recommendations with respect to the nature and degree of

those sanctions.

IT IS SO ORDERED.

Dated: April 2, 1990 /s/Spencer Williams

UNITED STATES

DISTRICT COURT JUDGE

No. 92-1544

In T h e

Supreme Court of tije iHmteb States

O ctober Te r m , 1992

P acific Legal Fou nda tio n ,

Petitioner,

v.

Paul Ka y fftz , et al,

Respondents.

O n Petition for a W rit of C ertiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Ninth Circuit

M OTION FO R LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AM ICI CURIAE

AND BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, IN C , AS AM ICI CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF THE PETITION FO R A

WRIT OF CERTIORARI

Antonia H ernandez

E. R icha rd Larson

Mexican American

Legal Defense and

Educational Fund

634 South Spring St.

Eleventh Floor

Los Angeles. CA 90014

(213) 629-2512

Elaine R. Jones

Charles Stephen Ralston

(Counsel of Record)

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Sixteenth Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

No. 92-1544

In T h e

Supreme Court of tfje Mmteb States

O ctober Te r m , 1992

Pacific Legal Fo u n d a tio n ,

Petitioner,

v.

Paul Ka y fe tz , et al,

___ _______ Respondents.

On Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Ninth Circuit

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF OF THE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND,

INC., AND THE MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND AS AMICI

CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF THE PETITION

FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc., and the Mexican American Legal Defense and

Educational Fund move the Court for leave to file the

attached brief amici curiae in support of the grant of a writ

of certiorari in the present case.1 The motion for leave to

file states the interest of amici.

The Petitioner has consented to the filing of the attached brief,

but respondent has refused consent.

( The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc. ( rLDF") is a non-profit corporation that was established

for the purpose of assisting black citizens in securing their

constitutional and civil rights. It was established in 1940 as

a legal aid society under the laws of the state of New York,

and is one of the oldest public interest legal organizations in

the United States. This Court has noted the Fund’s

"reputation for expertness in presenting and arguing the

difficult questions of law that frequently arise in civil rights

litigation." NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415, 422 (1963).

The Mexican American Legal Defense and

Educational Fund ("MALDEF') is a non-profit national civil

nghts organization headquartered in Los Angeles. Its

principal objective is to secure, through litigation and

education, the civil rights of Hispanics living in the United

States

2

As public interest legal organizations LDF and

MAL,DE^. haVC a deep concern with the use of a federal

courts "inherent power” to impose sanctions on

organizations seeking to carry out the Congressional policy

of private enforcement of the civil rights laws and other laws

impacting on the public interest. Further, we are concerned

with the use of the sanctioning power on plaintiffs and

private counsel who seek to vindicate their rights in federal

court.

We believe our long experience as public interest

organizations will be of assistance to the Court in deciding

whether to grant certiorari in this case. Therefore, we pray

3

that leave be granted to file the accompanying amicus curiae

brief in support of the petition for a writ of certiorari.

Charles Stephen Ralston

(Counsel of Record)

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Sixteenth Floor

New York. NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Antonia H ernandez

E. R ichard Larson

Mexican American

Legal Defense and

Educational Fund

634 South Spring St.

Eleventh Floor

Los Angeles, CA 90014

(213) 629-2512

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

M o tio n fo r Lea v e to F ile Br ie f Am icus Cu r ia e . 1

Ar g u m en t .................................................................................. 1

T h e D ecision Below Raises Im portant Q uestions

Con cern ing t h e Scope a n d M ea n in g o f this

C o u r t ’s D ecision in Cha m bers v . Nasco . Inc . . . . 1

C onclusion ............................................................................. 5

u

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Pages:

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975) . . . 3

Alyeska Pipeline Serv. Co. v. Wilderness Soc’y, 421 U.S.

240 (1975) ............................................................................5

Chambers v. Nasco. Inc., I l l S.Ct. 2123 (1991)......... 4, 5

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971)..............3

In re Primus, 436 U.S. 412 (1978).......................................4

Lockary v. Kayfetz. 974 F.2d 1166 (9th Cir. 1992) ............. 2

NAACP v. Button. 371 U.S. 415 (1963)....................... 2, 4

Sassower v. Fields. No. 92-1405, cert, denied, April 19,

1993 ....................................................................................... 5

Statutes and Rules: Pages:

28 U.S.C. § 1927 ..................................................... 2, 4, 5

Rule 11, F.R.Civ. Proc............................................... 2, 4, 5

Rule 23, F.R. Civ. Proc......................................................... 3

No. 92-1544

In T h e

Supreme Court of tfte Mmteb States

O ctober Te r m , 1992

Pacific Legal F o u n d a tio n ,

Petitioner,

v.

Paul Ka y fetz , et al,

Respondents.

On Petition for a W rit of C ertiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals

for the Ninth Circuit

BRIEF OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., AND THE MEXICAN

AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND AS AMICI CURIAE IN SUPPORT O F THE

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI

A r g u m e n t

T h e D ecision Below Raises Im portant Q uestions

Co n cern in g th e Scope and M ea n in g o f this

Co u r t s D ecision in Cham bers v . Na sco , In c .

I.

Amici believe that review of the Ninth Circuit’s

decision is particularly important because of the basis on

which that court justified the use of "inherent authority" to

impose sanctions on a not-for-profit public interest legal

2

organization that was supporting litigation. The decision

below was founded on assumptions about the manner in

which such an organization functions that are, with all due

respect ̂ not accurate. These assumptions were the basis of

the holding that the district court had the authority to

impose sanctions on the Pacific Legal Foundation even

though the foundation was not subject to Rule 11, F.R.Civ.

Proc 28 U.S.C. § 1927, or any other rule or statute that

provided for the imposition of sanctions.

"^lus* court below cited the acknowledgement of

Pacific Legal Foundation in its appellate brief that it seeks

to participate in precedent setting litigation in the public

interest as inconsistent with the Foundation’s position that

it was furnishing counsel to plaintiffs who could not

otherwise afford to bring suit. The court held that because

he Foundation’s goal was to "establish a legal precedent"

the plaintiffs were merely "nominal" and "were merely pawns

° r puf pets in thls effort." Lockary v. Kayfetz, 97 A F.2d 1166,

ici urge that the fact that an organization has as

one, or even a primary goal, the establishment of precedent

oes not in any way lead to the conclusion that the plaintiffs

in the lawsuits it supports are either nominal or "pawns or

puppets. rganizations such as the Foundation and amici

are limited in resources. They cannot serve as general legal

aid providers and represent everyone who seeks their

services, even if the cases are within the scope of their

purposes and expertise. They are necessarily selective, and

attempt to choose those cases that will have the greatest

impact either in terms of establishing precedent that can

hen be used by others in similar circumstances, or by

bringing actions that will in themselves affect many persons.

e ideal case, of course, is one that accomplishes both

purposes. r

Thus, an employment discrimination case brought as a class

“ '.h°d,rcal'hh lf ° r a 8n>Up of WOTkers at * Particular plan, can boih directly benefit the plaintiffs and establish a precedent that can

3

In either event, the interests of the real people with

real claims on whose behalf actions are brought are not only

central but, properly, paramount. Attorneys who work for

public interest organizations are fully aware of their ethical

obligations to represent the interests of their clients, and do

not subordinate them to the dictates of "a higher cause."

While the decision whether or not to take a case in the first

instance may be dictated by whether that case, among many

other possible cases, is compatible with and will further the

objectives of the organization, once representation has been

assumed, litigation decisions are made based on whether the

interests of the clients will be served.

For example, it is not uncommon that a case that was

taken as a vehicle for the vindication of a legal principle, will

result in a settlement that provides appropriate relief for the

plaintiffs. Organizations such as amici fully understand that

if such is the case, the settlement must be presented to their

clients and accepted on their behalf if that is their decision.

This is mandated not only by ethical standards, but also, in

the case of class actions, by the requirements of Rule 23,

F.R. Civ. Proc.

Of course, disagreements between public interest

lawyers and their clients may arise, just as they arise between

any other lawyers and their clients. If conflicts do arise, they

must and are resolved consistent with the ethical obligations

of the lawyers, and there are instances in which a public

interest legal organization may have to seek to be relieved

as counsel if the differences are irreconcilable. Although, in

the experience of amici, such instances are rare, they have

occurred in the many years of the our work.

Thus, certiorari should be granted to make clear the

extent to which, if any, the fact that an organization supports

litigation that is consistent with its purposes is a proper basis

benefit large numbers of other persons. Two examples from the

work-of LDF are Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 4G1 U.S. 424 (1971) and

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975).

4

for holding that it can be sanctioned for abuses that occur

during the course of the litigation. The activities of such

organizations have long been held to be protected by the

first amendment. NAACP v. Button, 371 U.S. 415 (1963); In

re Primus, 436 U.S. 412 (1978). The decision of the Ninth

Circuit has grave implications for the ability of such

organizations to carry out constitutionally protected activities

free of the chilling effect of the danger of the imposition of

sanctions based on pre-conceived notions of their role in

supporting litigation.

II.

Certiorari should also be granted in the present case

because it presents an opportunity for the Court to deal with

a broader issue of great importance for the guidance of the

lower courts, the proper application of the decision in

Chambers v. Nasco, Inc., I l l S.Ct. 2123 (1991). In Chambers

this Court affirmed the use of inherent powers to sanction

a party before the district court for actions taken by that

party in and out of court with the intent of impeding or

directly disobeying the rulings and orders of the court, such

out-of-court actions not being within the reach of the terms

of the various fees acts, Rule 11, section 1927, or other bases

for imposing sanctions. Rather than applying Chambers to

comparable factual situations, in a number of instances the

lower courts have extended Chambers far beyond its

appropriate reach.

Thus, Chambers involved a party who was responsible

for litigation carried out for abusive purposes and for out-of-

court actions designed to undermine the district court’s

jurisdiction. The award of sanctions was based on record-

based factual findings that established responsibility for the

sanctioned actions. In the present case, on the other hand,

the sanctions were based on assumptions that formed the

predicate for a holding that the named plaintiffs were not

the real parties in interest, but that rather an organization

that supported the litigation was. Moreover, the present

5

case involves alleged improper litigation conduct that

occured entirely in court, all of which could ahve been

reached through Rule 11 or section 1927. Yet the district

court resorted to the use of inherent power.

Another case that involves an unwarranted extension

of Chambers is Sassower v. Fields, No. 92-1405, cert, denied,

April 19, 1993. In that case, the court of appeals first held

that fee shifting was not proper under the fee provision of

the Fair Housing Act, that sanctions were not proper under

Rule 11 and only partly proper under section 1927, but then

affirmed the entire award of sanctions under the authority

of Chambers. The present case and Sassower, amici submit,

are indicative of a growing trend to undermine the American

Rule as explicated in Atyeska Pipeline Serv. Co. v. Wilderness

Socy, 421 U.S. 240 (1975), by swallowing it up through the

over-expansion of exceptions to it. We urge that it is

essential that the Court provide guidance to the lower

federal courts as to the proper scope and meaning of

Chambers v. Nasco, supra.

C o n c l u sio n

For the foregoing reasons, the petition for a writ of

certiorari should be granted.

Respectfully submitted.

Antonia Hernandez

E. Richard Larson

Mexican American

Legal Defense and

Educational Fund

634 South Spring St.

Eleventh Floor

Los Angeles. CA 90014

(213) 629-2512

Elaine R. Jones

Charles Stephen Ralston

(Counsel of Record)

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund. Inc.

99 Hudson Street

Sixteenth Floor

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae