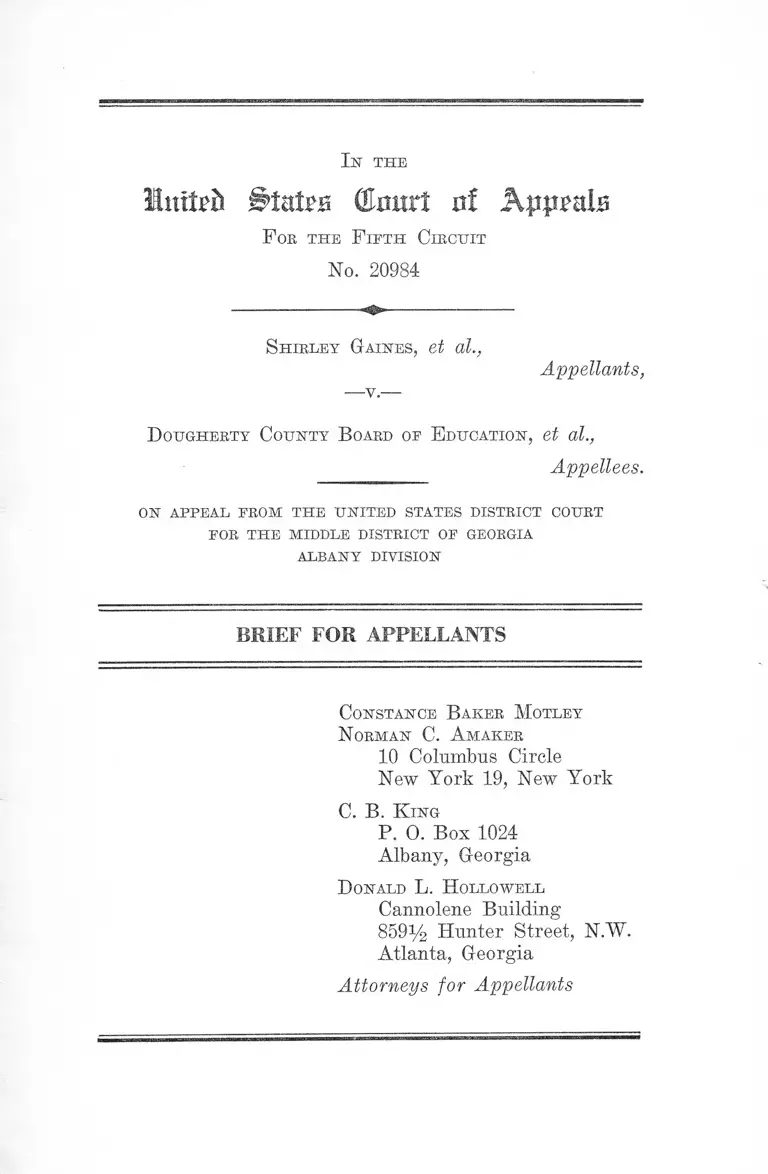

Gaines v. Dougherty County Board of Education Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

November 26, 1963

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Gaines v. Dougherty County Board of Education Brief for Appellants, 1963. 4dcb299d-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/576c8f23-d553-4c87-99fd-9f89b0f7f824/gaines-v-dougherty-county-board-of-education-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I;n t h e

Imtrd Butm (Court of AppraLs

F oe t h e F if t h C iec u it

No. 20984

S h ir ley G a in es , et al.,

Appellants,

D ougherty County B oard oe E ducation , et al.,

Appellees.

ON APPEAL EEOM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOE THE MIDDLE DISTRICT OF GEORGIA

ALBANY DIVISION

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Constance B aker M otley

N orman C. A m akee

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

C. B, K ing

P. 0. Box 1024

Albany, Georgia

D onald L. H ollo w ell

Cannolene Building

859% Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia

Attorneys for Appellants

I N D E X

Statement of the Case ........ ....................................... . 1

Specifications of Error .................................................. 6

A rgum ent I

Appellees’ Desegregation Plan Is Not a Plan by

Which Desegregation of the School System Can Be

Accomplished Nor Is the Twelve-Year Delay Con

templated by It Justified ........... ............................ 7

A rg u m en t I I

The District Court Erred in Refusing to Require

Appellees to Make a Start Toward Desegregation

in 1963-64 .................................... ............................ 13

Conclusion .................................... ............................ .................. —. 18

T able oe Ca se s :

Armstrong v. Board of Education of City of Birming

ham, 323 F. 2d 333 (5th Cir. 1963) ..................... 7,13,15

Augustus v. Board of Public Instruction, 306 F. 2d 862

(5th Cir. 1962) .............................................................. 8

Board of School Commissioners of Mobile County et al.

v. Davis,----- - U. S .----- , 11 L. ed. 2d 26 (Aug. 16,

1963) ............................- ............................ ................. 16

Boson v. Rippy, 285 F. 2d 43 (1960) ....................... . 12

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954) .......3, 7

Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294 (1955) ..7,13,17

PAGE;

11

Bush v. Orleans Parish School Board, 308 F. 2d 491

(1962) ................................ ........................................... 7, 8

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 (1958) ............ .............7,12,17

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, Alabama, 318 F. 2d 63 (1963) ........... .......... 12

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, 322 F. 2d 356 (5th Cir. 1963) ....................... 15

Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Board, 219

F. Supp. 876 (E. D. La. 1963) ............... ................... 14

Evans v. Ennis, 281 F. 2d 385 (3rd Cir. 1960) ______ 12

Goss v. Board of Education of the City of Knoxville,

301 F. 2d 164 (6th Cir. 1962) ................. ..................... 12

Goss v. Board of Education of the City of Knoxville,

373 U. S. 683, 10 L. ed. 2d 632 (1963) .......... ...........11,13

Harris v. Gibson and Glynn County Board of Educa

tion (No. 20871, Sept. 12, 1963) ____ ______ _____ 15

Hereford v. Huntsville Board of Education (No. 63-109,

N. D. Ala., August 13, 1963) ................... ............14,15-16

Holland v. Board of Public Instruction, 258 F. 2d 730

(1958) ................................. ...................................... . 7

Jackson v. School Board of City of Lynchburg, Va.,

321 F. 2d 230 (4th Cir. 1963) __ ______ ______ ___10,12

Jones v. School Board of the City of Alexandria, 278

F. 2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960) ...... ........................................ 8

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 221 F. Supp.

297 (M. D. Ala. 1963) .................. ............................. 14

Louisiana State Board of Education v. Allen, 287 F. 2d

32 (5th Cir. 1961), cert. den. 368 U. S. 830

PAGE

11

Ill

Louisiana State Board of Education v. Angel, 287 F. 2d

PAGE

33 (5th Cir. 1961) ....... ..................... ..... ................___ n

Northcross v. Board of Education of the City of Mem

phis, 302 F. 2d 818 (6th Cir. 1962) ........... ............. .8,10

Potts v. Flax, 313 F. 2d 284 (1962) ......................... 7

Rippy v. Borders, 250 F. 2d 690 (1957) ........... ............. 7

Stell v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Educa

tion, 318 F. 2d 425 (5th Cir. 1963) ........................... 15

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526, 10 L. ed.

2d 529 ..............................................................11,13,14,16

I n t h e

United (Emtrt nf Appeals

F oe t h e F if t h Cib c u it

No. 20984

S h ib ley Ga in es , et al.,

Appellants,

D ougheety C ounty B oabd of E ducation , et al.,

Appellees.

on appeal fbom t h e u n ited states distbict coubt

FOB THE MIDDLE DISTBICT OF GEOBGIA

ALBANY DIVISION

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

Statement of the Case

This appeal presents for review the plan of desegrega

tion offered by the Dougherty County Board of Education

(Albany, Georgia) and the action of the United States Dis

trict Court for the Middle District of Georgia, Albany Divi

sion in approving that plan over appellants’—plaintiffs

below—objections. The order appealed from was entered

by District Judge Elliott with opinion on August 27, 1963

(B. 146-156).

By an earlier order and opinion (July 12, 1963, R. 23-30)

the district court had required the school board to submit a

desegregation plan after finding that the board was operat

ing a racially segregated school system (R. 2S). This find

2

ing was based on 1) a complaint filed by plaintiffs, minors

of the Negro race and their parents, on April 5, 1963 as a

spurious class action against the school board and the super

intendent of schools alleging that the school authorities

were operating a compulsory biracial school system in

Dougherty County including the maintenance of a dual set

of school zone lines and initial racial assignments thereafter

perpetuated by a racially oriented feeder system and that

the assignment of professional school personnel was like

wise made on a racial basis. The complaint prayed a decree

enjoining the operation of the dual racial system and alter

natively prayed that the court direct defendants to present

a desegregation plan (R. 1-12); 2) an answer (R. 20) in

which operation of a dual educational system was admitted

by the defendants; and 3) a hearing held on July 8, 1963

on a motion for preliminary injunction filed by plaintiffs on

May 2, 1963 repeating the prayer of the complaint (R. 16).

The order of July 12 required the defendants to submit

a desegregation plan to the court within 30 days (R. 29).

The plan was submitted on August 12, 1963 (R. 30). The

plan, though submitted before the scheduled opening of the

schools in September, did not provide for any start toward

desegregation in the 1963-64 school year but postponed ini

tiation of the desegregation process until 1964-65, and con

templated a twelve-year period before that process would

be completed.

Under the plan, existing racial assignments were to re

main unchanged and pupils entering the first grade in 1964-

65 were to register at the schools of their choice during a

county-wide registration period set up under the plan to be

held beginning the first Monday in April and continuing

through Friday of that week. This “free choice” of the

pupils was limited however by their proximity to the school,

the building capacity, and transportation. The plan further

3

provided that this “free choice” was to be acted upon by the

board as requests for assignment and specified that notice

of the board’s action on these “free choice” requests was to

be transmitted to the parents or guardians of the children

involved no later than June 1, 1964 with a right thereafter

on the part of the parent or guardian to request in writing

a hearing before the board if not satisfied with the assign

ment which hearing was to be held on or before June 20,

1964. Finally, the plan provided that this procedure was

to be followed in each ensuing year one grade at a time

(R, 30-33).

Plaintiffs, in objections filed with the court on August

14,1963 complained of the defendants’ plan in the following

respects:

1. That the plan failed to make a start toward desegrega

tion in the 1963-64 school year;

2. That the plan’s “free choice” provision was illusory

because this provision did not insure desegregation of the

schools in 1964-65 since it did not clearly provide that new

pupils entering the first grade or coming into the county

for the first time would attend schools as a matter of right

in the residential areas in which they live;

3. That the plan did not abolish the dual school zones

but continued the assignment of school children within the

framework of the existing segregated system which system

included the assignment of teachers and other supervisory

personnel on a racial basis;

4. That the defendants had not shown that the twelve-

year period contemplated under the plan was necessary

and this showing was crucial particularly since more than

9 years had elapsed since the decision in Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U. S. 483 (1954).

4

5. Plaintiffs further objected to the plan on the ground

that the named plaintiffs were not assured of securing their

personal and present right to a desegregated education.

6. Finally, plaintiffs objected on the ground that the

plan failed to provide a method for the present desegrega

tion of the separate vocational schools maintained by the

county on a racial basis. Accordingly, plaintiffs prayed

that the plan be disapproved, a revised plan submitted

and “minimum effective relief” be granted by requiring a

start toward desegregation in September 1963 (E. 34-36).

Hearing was held by the District Court on the objections

on August 22, 1963 (E. 37) at which the testimony of the

Superintendent of Schools was offered in justification of

the plan. He testified that the failure to make a start

toward desegregation in 1963-64 and the twelve-year period

of delay was necessary because: (1) The assignments of

pupils and teachers and the allocation of books for the 1963-

64 school year had already been made (E. 52), and (2)

time was needed to prepare the community to accept de

segregation in order that an orderly transition could be

made from the segregated system to a nonsegregated sys

tem (E. 43-44, 46-48, 57, 59, 62-63). In fact, community

hostility was presented as the major reason for not having

the plan go into effect in September 1963 (E. 104). How

ever, the Superintendent could point to nothing specific

to buttress his claim that initial forbearance and gradual

accommodation thereafter would in fact aid community

acceptance (E. 61). With respect to making a start toward

desegregation by admitting a few Negro students to previ

ously all-white schools in September 1963 as had been done

by other communities such as Savannah, Georgia; Mobile,

Birmingham, Tuskegee and Huntsville, Alabama and Baton

Eouge, Louisiana, it was his view that granting admission

5

to the named plaintiffs (as had been suggested) to the

schools of their choice for the coming school year would be

to grant “special privileges” to them which would place

the board in an “untenable position” (R, 55, 59). Therefore,

the Superintendent felt that it was impossible to make a

start in 1963-64 even though under the plan the plaintiffs

who brought the suit would never experience any desegre

gated education (R. 64).

Other testimony by the Superintendent exposed addi

tional weaknesses in the plan. For example, he testified

that there are separate zone lines for the Negro and white

schools (R. 74) but the plan makes no provision for redraw

ing these lines (R. 78); that the plan makes no provision

for the placement of students coming into the county for

the first time in grades above the first in schools on a non-

racial basis (R. 81); that the plan makes no provision for

desegregation of the two vocational schools maintained

separately for Negroes and whites because these schools

are a joint operation of the state and county boards of

education and consent of the state board would have to be

obtained in order to desegregate them even though there

is no written agreement between the county and state

boards requiring segregated operation (R. 78-80).

The major deficiency of the plan as illuminated by the

Superintendent’s testimony is that the “free choice” of

students is qualified in such a way as to render assurance

of desegregation impossible. He testified that desegrega

tion would result only if a Negro applied for admission

to a formerly all-white school, if the applicant lived nearer

to that school than to some other school, if there was room

in the school, and if there was no transportation problem

(R. 83-84). Hence according to his testimony, no desegrega

tion will result if there are no Negro applicants for “white”

schools (R. 84, 97, 99).

6

On August 27, 1963 Judge Elliott entered the order ap

pealed from here (E. 146). That order upheld the sub

mitted plan in every particular finding it “to be reasonable

and adequate to accomplish the desired results (of desegre

gation).” The court, feeling that “ [a] surcease from sensa

tion” was desired, held that to order any degree of desegre

gation for September 1963 “would be at variance with the

concept of ‘deliberate speed’ and would be a rash act caus

ing unnecessary confusion in the administration of the

schools . . . ” With respect to plaintiffs’ urging that a

start be made in 1963-64 by requiring the board to assign the

named plaintiffs to the schools of their choice, the court

stated that this “would have the effect of inviting the de

struction of the . . . plan.” The court also refused to rule

on the question of teacher assignment or to require desegre

gation of the vocational schools (E. 154-155).

Notice of Appeal was filed on September 3, 1963 (E.

157-158).

Specifications of Error

The District Court erred in:

(1) refusing to order the named plaintiffs admitted to

the schools of their choice for September 1963;

(2) considering community hostility as a grounds for de

laying desegregation until the 1964-65 school year;

(3) failing to order the abolition of existing school zone

lines based on race and the reorganization of the

public school system on a nonracial basis;

(4) refusing to provide for the assignment of teachers

and other professional personnel without regard

to race or color;

7

(5) failing to order desegregation in the vocational

schools operated by the board;

(6) approving the “grade-a-year” provision of the plan

which nine years after Brown proposes to delay

desegregation of the connty schools yet another

twelve years.

A R G U M E N T

I.

Appellees’ Desegregation Plan Is Not a Plan by Which

Desegregation of the School System Can Be Accom

plished Nor Is the Twelve-Year Delay Contemplated by

It justified.

1. Despite the monumental clarity with which both de

cisions in Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483

(1954), 349 U. S. 294 (1955) and Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S.

1 (1958) as well as numerous decisions of this court, Rippy

v. Borders, 250 F. 2d 690, 693 (1957) ; Holland v. Board of

Public Instruction, 258 F. 2d 730, 733 (1958); Bush v. Or

leans Parish School Board, 308 F. 2d 491, 499 (1962); Potts

v. Flax, 313 F. 2d 284 (1962) and Armstrong v. Board of

Education of Birmingham, 323 F. 2d 333, 337 (1963) have

enjoined upon school officials the primary duty of eliminat

ing system-wide racial segregation in the administration

of public schools, the desegregation plan offered by the

school board here and approved by the District Court fails

utterly as a means for accomplishing this crucial task.

The reluctance by Dougherty County officials to discharge

their responsibility of total desegregation throughout the

school system is seen most clearly, though not at all en

tirely, in their submission of a plan containing an illusory

“free choice” provision in the context of the continued

8

maintenance of a dual scheme of zone lines for white and

Negro schools. There is unanimous agreement among all

the federal circuit courts that have passed upon school

desegregation cases that a threshold requirement for com

plying with the Brown decisions is the elimination of dual

zones based on race. Augustus v. Board of Public Instruc

tion, 306 F. 2d 862, 869 (5th Cir. 1962); Bush v. Orleans

Parish School Board, supra; Jones v. School Board of the

City of Alexandria, 278 F. 2d 72, 76 (4th Cir. 1960); North-

cross v. Board of Education of the City of Memphis, 302

F. 2d 818, 823 (6th Cir. 1962). Nothing less than the eradi

cation of the dual zones fulfills the obligation of school

officials to disestablish the segregated school systems pre

viously established by them.

Manifestly, the school board here has not assumed its

obligation of disestablishment. It has maintained the dual

system (R. 74, 78) and proposed to admit Negro applicants

to formerly all-white schools under a “free-choice” arrange

ment closely analogous to the Parent School Preference

Card System held inadequate in Augustus v. Board of Pub

lic Instruction, supra, where this court stated that, “The

plan should . . . more clearly provide for the admission

of new pupils entering the first grade, or coming into the

County for the first time, on a nonracial basis” (306 F. 2d at

369). Under the provisions of the plan involved here,

no provision is made for new pupils coming into the county

for the first time to attend school on a non-racial basis

and there is no assurance that any actual desegregation

of the first grade will occur in 1964 (as would be assured

if the school lines were redrawn and every child who lived

in the zone of a school serving that zone were simply as

signed to that school by the board irrespective of his race)

since the “free choice” of those seeking desegregation is

circumscribed in such a way as to require Negro students

to apply to the schools they desire to attend if there’s to be

9

any desegregation at all.* Hence, under this plan, Negro

children and their parents must once again assume the bur-

* This was brought out repeatedly at the hearing on the objec

tions to the plan in the following exchanges between counsel for

the plaintiffs and the chief witness, the school superintendent:

1) Q. Mrs. Motley: And you’re not able to demonstrate to this

Court, are you, that this plan will in 1964 result in the ad

mission of some Negroes to white schools? A. I can assure

you that it will.

Q. All right, now we want to know how that can be assured?

A. Well, there are some who live, their nearest school they

live nearer today; there are some today who live nearer to

schools that are being operated all white schools than they

do to schools that are Negro schools; and some of those

students will be admitted; probably not all that make appli

cation, but certainly there will be some that will be.

Q. And you can say to this Court that you’re sure that there

are some white schools where Negroes live closer than they

do to Negro schools, which are under-enrolled and which

would not involve any transportation problem; so that, if

those Negroes apply, they would go in, is that right? A. They

probably will, yes.

Q. Probably will? A. Yes, under this plan, they would.

Q. In other words, it’s not certain, is it? First, you’ve got

to have a Negro to apply, isn’t that right? A. That’s right.

Q. Then, you’ve got to have a Negro who lives nearer to a

white school, isn’t that right? A. That’s right.

Q. And then, you’ve got to have room in that school .for that

student, isn’t that right? A. That’s right.

Q. And then, you have to have a student that doesn’t have

any transportation problem, isn’t that right? A. Yes.

Q. So, you’ve got four factors operating there, all of which

must come together in order for the Negro to get in? A.

That’s right.

Q. So that, if no Negro applies next year, you’re not going

to have any desegregation, are you? A. I wouldn’t think so

[E. 83-84].

2) Q. Let me ask you this, in other words, if no Negro applies

in April, 1964, I think you admitted before there wouldn’t

be any desegregation, is that right? A. That’s right

[K, 97-98].

3) Q. And if no Negro applies, you just go on and operate

segregated schools, right? A. That’s right [E. 99].

10

den of going forward and asking for their constitutional

rights. But as the Sixth Circuit said in Northcross v.

Board of Education of the City of Memphis, supra, “Negro

children cannot be required to apply for that to which they

are entitled as a matter of right” (302 F. 2d at p. 823).

2. Neither has the burden for disestablishing the segre

gated school system been met by the failure of the board’s

plan to provide for the desegregation of teachers and other

staff personnel or the indefinite postponement by the Dis

trict Court of the consideration of the assignment of

teachers on a nonracial basis. If desegregation of the school

system is not to be an empty bauble, then the major sup

port of segregated systems that is found in the fact that

in front of every Negro class there is a Negro teacher and

in front of every white class there is a white teacher must

be removed. Full compliance with Brown’s requirement that

racially discriminatory school systems must be replaced

by racially nondiscriminatory systems requires the reas

signment of teachers and other staff personnel on the basis

of qualification and need without regard to race. In Jack-

son v. School Board of the City of Lynchburg, Va., 321

F. 2d 230 (1963) recently decided by the Fourth Circuit,

that court stated its view that the complaint’s prayer call

ing “for an order compelling the board to ‘effect . . . a

transition to a racially non-discriminatory school system’

. . . is broad enough to comprehend all aspects of the schools’

operations.” 321 F. 2d at 233. It is submitted that this is

the only view that conforms with Brown’s requirement that

a transition to racially non-discriminatory school systems

be made. Cf. Northcross v. Board of Education, supra,

p. 823:

The first Brown case decided that separate schools

organized on a racial basis are contrary to the Con

stitution of the United States.

11

3. The plan submitted by the board and approved by the

court also made no provision for desegregation of the two

vocational schools under the board’s jurisdiction. Though

the superintendent testified that these schools were a joint

operation of the appellee school board and the state school

board, his testimony made clear that primary responsibility

for the policy of segregation was with the local board (E.

79). Consequently, the failure of the board to provide for

desegregation of the vocational schools was another in

stance of its untrammeled reluctance to disestablish the

segregation that it had established. And of course, even if

the state board of education were alone responsible for

segregation of the vocational schools, their desegregation is

still required. Louisiana State Board of Education v. Allen,

287 F. 2d 32 (5th Cir. 1961), cert. den. 368 U. S. 830;

Louisiana State Board of Education v. Angel, 287 F. 2d

33 (5th Cir. 1961).

4. A further vice of the board’s plan is the twelve-year

span of implementation. As the Supreme Court recently

made clear in Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526,

10 L. ed. 2d 529, and Goss v. Board of Education of the City

of Knoxville, 373 U. S. 683, 10 L. ed. 2d 632, the time al

lotted to school boards for completion of the desegregation

process is rapidly decreasing. As the Court said in Watson:

Given the extended time which has elapsed, it is far

from clear that the mandate of the second Brown deci

sion requiring that desegregation proceed with “all de

liberate speed” would today be fully satisfied by types

of plans or programs for desegregation of public educa

tional facilities which eight years ago might have been

deemed sufficient. 373 U. S. 526,----- , 10 L. ed. 2d 529,

534.

12

Now, more than nine years after the Brown decision, this

school board has proposed a plan, accepted by the District

Court, which compounds its deficiencies by proposing to

delay desegregation for twelve more years.

Increasingly, courts passing on desegregation plans, have

been manifesting their impatience with the action of school

officials who operate on the assumption that they have no

duty to change the status quo until ordered to do so by a

court and who, theretofore, having taken no steps to “ [de

velop] arrangements pointed toward the earliest practicable

completion of desegregation,” Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1,

7, have then proposed “grade-a-year” plans perpetuating

the frustration of the enjoyment of constitutional rights.

This Court in Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of

Mobile County, Alabama, 318 F. 2d 63, 64 (1963) stated that

“ . . . the amount of time available for the transition from

segregated to desegregated schools becomes more sharply

limited with the passage of the years since the first and

second Brown decisions” and in Boson v. Bippy, 285 F. 2d

43 (1960), this Court approved a grade-a-year plan as a

start but stated that, “In so directing, we do not mean to ap

prove the twelve-year stair-step plan insofar as it post

pones full integration’” (at page 47). See also Evans v.

Ennis, 281 F. 2d 385, 389 (3rd Cir. 1960); Goss v. Board of

Education of the City of Knoxville, 301 F. 2d 164 (6th Cir.

1962), reversed on other grounds, 373 U. S. 683 (1963);

Jackson v. School Board of City of Lynchburg, Va., supra,.

In Jackson the Fourth Circuit considering the Supreme

Court’s decision in Watson, supra, held that “the ‘grade-a-

year’ plan promulgated by the Lynchburg School Board, for

initial implementation eight years after the first Brown

decision, cannot now be sustained” (at page 233).

13

II.

The District Court Erred in Refusing to Require Ap

pellees to Make a Start Toward Desegregation in 1963-

64=

Not only did the District Court err in approving a plan

grossly inadequate to accomplish the task of converting the

present dual biracial school system of Dougherty County

into a unitary nonracial system (I supra), it also refused

to order appellees to make “at the very minimum, . . . a

good faith start toward according the plaintiffs and the

members of the class represented by them their constitu

tional rights so long delayed.” Armstrong v. Board of

Education of City of Birmingham, 323 F. 2d 333, 338 (5th

Cir. 1963) (emphasis added). For the Supreme Court in

the second Brown case was insistent that the District

Courts, to whose care was committed the implementation

of the constitutional principles announced in the first Brown

case, should in performing this function, “require that the

defendants make a prompt and reasonable start toward full

compliance with our May 17, 1954 ruling.” 349 U. S. 300.

Yet, nine years after the first Brown decision and more

than eight years after the Supreme Court had ruled that

school officials were required to “make a prompt and reason

able start,” no start towards desegregation has been made

by the Dougherty County school officials. Dougherty County

in this respect, is no different from countless numbers of

other localities in which officials choose to emphasize “de

liberate” rather than “speed.” Consequently, in its last

term, the United States Supreme Court, in Watson v. City

of Memphis, 373 U. S. 526, 10 L. ed. 2d 529 and Goss v.

Board of Education of the City of Knoxville, 373 U. S. 683,

10 L. ed. 2d 632, expressed an understandable impatience

with school officials, like those involved here, who choose to

14

ignore rather than to comply with the clear mandate of the

Brown decisions. The Supreme Court said in Watson that,

“Brown never contemplated that the concept of ‘deliberate

speed’ would countenance indefinite delay in elimination of

racial barriers in schools . . . ” 373 U. S. 526,----- , 10 L. ed.

2d 529, 534.

Perceiving the clear warning gleaned from the opinions

in the Watson and Goss cases that the United States Su

preme Court was growing increasingly intolerant of further

delay in performing the necessary task of school desegrega

tion, several District Courts, during the past summer, in

ruling on school segregation suits against school officials

of communities which had not theretofore taken any steps

toward desegregation (like the Dougherty County school

officials), were scrupulous in requiring these school officials

“at the very minimum” to make a start in the conversion of

their biracial school systems. Among these were Baton

Rouge, Louisiana, Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School

Board, 219 F. Supp. 876 (E. D. La. 1963); Huntsville, Ala

bama, Hereford v. Huntsville Board of Education (No. 63-

109, N. D. Ala., August 13, 1963); and Tuskegee, Alabama,

Lee v. Macon County Board of Education, 221 F. Supp. 297

(M. D. Ala. 1963). The District Courts which considered

these cases required some minimal desegregation of the

schools commencing in September 1963, thus performing

the duty imposed upon them by the Supreme Court without

the necessity of intervention by this Court.

Other District Courts, however, failed to grant to plain

tiffs in school cases arising in other communities during

recent months, the relief to which they were entitled and,

consequently, this Court on review had to assume the re

sponsibility for implementing the governing constitutional

principles. Among the communities that were required by

order of this Court to make a start toward desegregation

15

in the current school year, were Savannah, Georgia, Stell

v. Savannah-Chatham County Board of Education, 318 F.

2d 425 (5th Cir. 1963); Birmingham, Alabama, Armstrong

v. Board of Education of City of Birmingham, supra; and

Mobile, Alabama, Davis v. Board of School Commissioners

of Mobile County, 322 F. 2d 356 (5th Cir. 1963). In all

of these cases whether decided alone by the District Courts

or whether pursuant to the orders of this Court, the method

used for implementation of some measure of desegrega

tion was that of requiring the appropriate school officials

to admit at least a few Negro school children to formerly

all-white schools in September 1963.#

Plaintiffs below, in view of the fact that the school

board’s plan was not presented to the District Court until

August 12, 1963 and the hearing on their objections was

not held until August 22, 1963, less than two weeks prior

to the scheduled opening of the Dougherty County Schools,

asked the District Court to order the defendants to do no

more than these other communities had been required

to do for the purpose of complying initially with the pre

script of Brown that a start be made, viz., that some Negro

children be placed in the county schools in September 1963,

and that those children be the plaintiffs named in the suit

since as to them there was no conceivable problem that the

board could have in placing them. This is what Judge

Grooms of Alabama’s Northern District did in the Hunts

ville school case. Hereford v. Huntsville Board of Educa-

* However, in Glynn County, Georgia, the school board had

voluntarily undertaken to begin desegregation in September when

it was prevented from doing so by the District Court. Accordingly,

this Court vacated the District Court’s restraining order and

granted an injunction pending appeal framed in the same terms

as that issued earlier with respect to Savannah (Stell, supra)

pursuant to which six Negro children were admitted to the for

merly all-white high school in September. Harris v. Gibson and

Glynn County Board of Education, No. 20871, Sept. 12, 1963.

16

tion, supra, in which the four named plaintiffs were ad

mitted to the schools of their choice for the purpose of

making a start.

And as Mr. Justice Black concluded in declining to grant

a stay of this Court’s order requiring Mobile School officials

to make a sta rt:

I t is difficult to conceive of any administrative prob

lems which could justify the Board in failing in 1963

to make a start towards ending the racial discrimina

tion in the public schools which is forbidden by the

Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment as authoritatively determined by this Court in

Brown nine years ago. Board of School Commission

ers of Mobile County et al. v. Davis,----- U. S . ------ ,

11 L. ed. 2d 26, 29 (Aug. 16, 1963).

Notwithstanding, the somewhat baffling reaction of the

District Court here was that to grant this relief in

Dougherty County “would have the effect of inviting the

destruction of the . . . plan” proposed by the school board

(R. 154). Aside from being the most reasonable expedient

in the circumstances, to have admitted the named plain

tiffs to the schools of their choice in September 1963 would

have been to recognize their personal and present right

to be freed from invidious discrimination with respect to

school attendance because of their race. As the second

Brown case makes clear, “ [a]t stake is the personal in

terest of the plaintiffs in admission to public schools as

soon as practicable on a nondiscriminatory basis.” 349

U. S. 300 (emphasis added). Cf. Watson v. City of Mem

phis, supra: “the rights here asserted are, like all such

rights, present rights; they are not merely hopes to some

future enjoyment of some formalistic constitutional prom

ise.” 373 U. S. 526,----- -, L. ed. 2d 529, 535.

17

At the hearing on the plan the Superintendent of Schools

initially claimed that he and the other school officials could

not place the named plaintiffs in the schools of their choice

in September 1963 (aside from the fact that, in his view,

to do so would be to grant “special privileges” to them

(R. 59)), because they would be prevented from doing so

by the problem of the “mechanics” of making such an

adjustment in light of the fact that all assignments had been

made for the coming school year (R. 48). However, when

pressed by counsel for the plaintiffs, he admitted that

if 200 students were to have moved into the county prior

to the opening of school in September and were to have

applied for admission to the schools the system, would

somehow have found a way to accommodate them (R. 50,

52-53). Ultimately, he was constrained to admit that the

mechanics of handling the transfer of the named plaintiffs

to formerly all-white schools in 1963 was actually “a minor

problem” (R. 86), and that his major reason for claim

ing that it was impossible to admit the named plaintiffs

was due to the anticipated community hostility to making

a change from the former segregated system (R. 104). As

a reason for delaying school desegregation, community

hostility has never been entitled to any consideration

whatsoever. Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294,

300; Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 16. For as was pointed

out by counsel for the plaintiffs during the course of the

hearing, the factor of community hostility to desegrega

tion makes the factor of race operative in the considera

tion of making assignments to the schools (R. 102-103).

As thus exposed, the real reason for refusing to make a

start toward desegregation, commended by the District

Court in terms of “a surcease from sensation” (R. 154),

is a reason that has never been and cannot ever be allowed

to frustrate a claim of constitutional right.

18

CONCLUSION

The judgment of the District Court approving appellees’

plan and refusing to order a start toward desegregation in

September 1963, should be reversed and the case remanded

to that court with directions to require the School Board to

initiate desegregation for the coming mid-year semester

and to submit a revised plan covering the objections made

by Appellants pursuant to which the dual school system

will be disestablished commencing with the 1964-65 school

year. Since it is now too late for a start to be made for

the current semester, the named plaintiffs should be ad

mitted to the schools of their choice for the 1964 winter

semester only for the purpose of initiating the desegrega

tion process and thereafter desegregation should occur in

conformity with the revised plan which under no circum

stances should be permitted to encompass a period of twelve

years.

Respectfully submitted,

C onstance B aker M otley

N orman C. A maker

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

C. B. K ing

P. 0. Box 1024

Albany, Georgia

D onald L. H ollo w ell

Cannolene Building

859!/2 Hunter Street, N.W.

Atlanta, Georgia

Attorneys for Appellants

19

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

This is to certify that on the 26th day of November, 1963,

I served a copy of the foregoing Brief for Appellants

upon Jesse W. Walters, 409 North Jackson Street, Albany,

Georgia, Attorney for Appellees, by mailing a copy thereof

to him at the above address via U. S. mail, Air Mail, postage

prepaid.

Attorney for Appellants

q3a||| |^ p 38