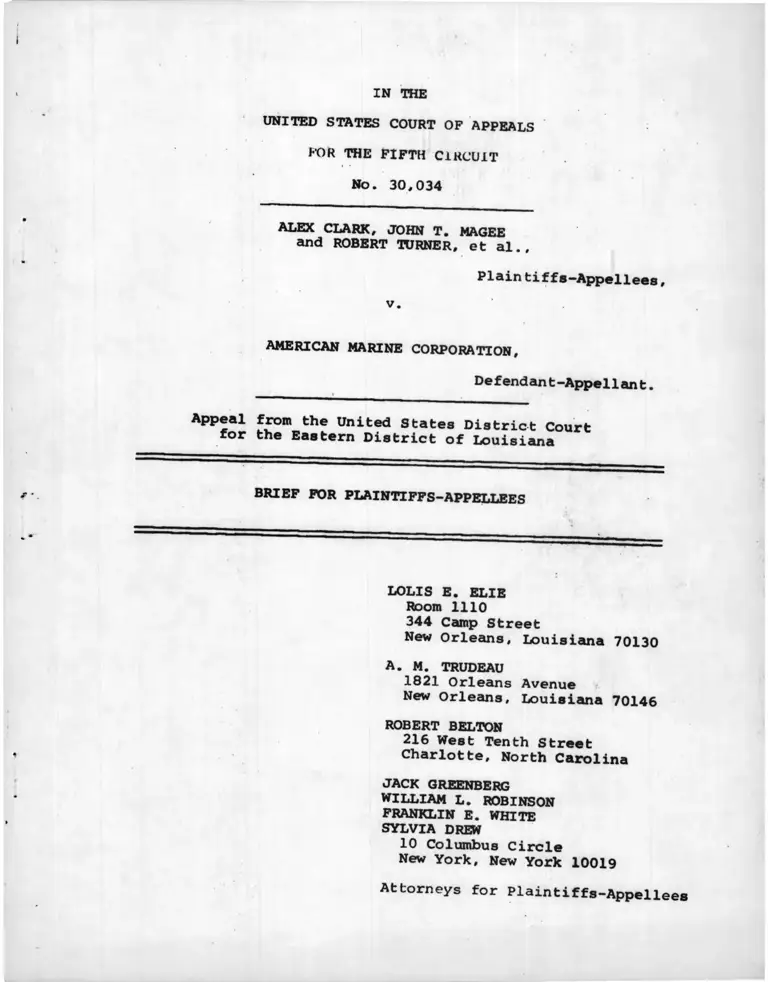

Clark v. American Marine Corporation Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellees

Public Court Documents

September 11, 1970

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Clark v. American Marine Corporation Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellees, 1970. 9fcecd8c-ad9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/578c096c-ac6e-495e-96b7-9f9d0e33e094/clark-v-american-marine-corporation-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellees. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 30,034

ALEX CLARK, JOHN T. MAGEE

and ROBERT TURNER, et al.,

Plain tiffs-Appellees,

v.

AMERICAN MARINE CORPORATION,

Defendan t-Appellant.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Louisiana

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

LOLIS E. ELIE

Room 1110

344 Camp Street

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

A. M. TRUDEAU

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana 70146

ROBERT BELTON

216 West Tenth Street

Charlotte, North Carolina

JACK GREENBERG

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

FRANKLIN E. WHITESYLVIA DREW

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appellees

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Faae

Counter Statement of the Issue Presented for Review . . . 1

Counter Statement of the C a s e .......................... 1

Argumen t:

I. Introduction .................................. g

II. Counsel Fee Awards to Successful Plaintiffs

in Title VII Actions May Not Be Denied,

Limited or Otherwise Reduced Because Some

or All of Their Counsel Were Affiliated

with a Legal Aid Organization.................. 7

III. Appellees' Attorneys' Efforts to Settle This

Case Without Litigation Were Earnest and

Reasonable and Were Unsuccessful Due Only to

the Disinterest of Appellant in Further

Settlement Negotiation......................... 1 5

IV. The Plaintiffs' Estimate of Time and Value

of Their Services Were Reasonable in the

Circumstances of This Case......... ............

V. The District Court Did Not, on This Record,

Abuse Its Discretion by Allowing Costs......... 24

Conclusion............................................ 26

Certificate of Service ............................ 27

Table of Cases:

Bowe v. Colgate, 272 F. Supp. 332 (S.D. Ind. 1967),

reversed in part on other grounds, F.2d

61 CCH Lab. Cas. 5 9326 (7th Cir. 1969) . .~T\ . . 10

Broussard v. Schlumberger Well Services, No. 68-H-215

(S.D. Texas, Aug. 4, 1970)........................ H

Carter v. Hoit-Williamson Mfg. Co., 62 CCH Lab. Cas.

H 9436 (E.D. N.C. 1969) n

Cheatwood v. South Central Bell Telephone and

Telegraph Company, ___ F. Supp. , 60 CCH Lab.

Cas. f 9299 (M.D. Ala. 1969) . . . 10

1

Table of Cases Cont'd) Page

Chicago Sugar Co. v. American Sugar Co., 176 F 2d 1

(7th Cir. 1949)........................ ‘.........24.25

Clarke v. American Marine Co., 304 F. Supp. 603

(E.D. La. 1969) .................... 2

Culpepper v. Reynolds Metals Co., No. 12,179 (N D

Ga., August 13, 1970) . . ...............] ' 1 1

Dewey v. Reynolds Metals, 300 F. Supp. 709 (W D

Mich. 1969).......................................... X1

Dobbins v. Electrical Workers (IBEW) Local 212

61 L.C. f 9327 (S.D. Ohio 1969)................... 7,8,13

Dobbins v. IBEW. Local 212, 292 F. Supp. 413 (S DOhio 1 9 6 8 ) ........ * *.............................................. 10

Garner v. E. I. duPont, 60 CCH Lab. Cas. f 9300

(W.D. Ky. 1969).................. * .......... n

Jenkins v. United Gas, 400 F.2d 28 (5th Cir. 1968) . 10,12,20

Johnson v. Seaboard Airline Railroad Co., 405 F 2d

645 (4th Cir. 1968)................ .. . ! . g

Long v. Georgia Kraft Co., 62 CCH Lab. Cas. I 9437

(N.D. Ga. 1970).............. ..

Miller v. Amusement Park Enterprises, Inc., p 2d

--- (No. 27.529, 5th Cir., May 13, 19707“ . ] 6,13,14,23

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, 390 U.S 400

(1968) ...................................... 6,9.10.12

Petway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co., 411 F.2d 998

(5th Cir. 1969)............................. 1X

Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 279 F. Supp. 505

(E.D. va. 1968)................. 10>24

Richards ^Griffith Rubber Mills. 300 F. Supp. 338

• • • • • • • • 11*19

Sprpgls v. United^Airlines, Inc.. 308 F. Supp. 959

........ * * • • • • • • 1 1

United States v. Local 189, UPP., 301 F. Supp. 906,

60 CCH Lab. Cas. f 9247 (E.D. La. 1969). . . . . i0,24

i i

Statutes: Page

28 U.S.C. § 1920 ........................

42 U.S.C. § 1981, Civil Rights Act of 1870

42 U.S.C. §§ 2000-e et seq., Civil Rights Act of

1964, Title VII . . ......................

Other Authorities;

Civil Rights Bill of 1963, H.R. 7152, 8 8th Conq.,

1st Sess. (1963) ..............

Rule 54, F.R.C.P.........

in

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 30,034

ALEX CLARK, JOHN T. MAGEE

and ROBERT TURNER, et al.,

Plaint iffs-Appellees,

v.

AMERICAN MARINE CORPORATION,

Defendant-Appellant.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Louisiana

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

COUNTER STATEMENT OF THE ISSUE

PRESENTED FOR REVIEW

Whether the district court erred in its determination of

the proper amount of attorneys' fees to be awarded as provided

by Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

COUNTER STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This is an appeal from a judgment of the United States

District Court for the Eastern District of Louisiana, the

Honorable Alvin B. Rubin, entered on April 28, 1970, awarding

$21,974.51 in counsel fees and costs to appellees (plaintiffs

below). The opinion ol the court dealing with fees and costs

is at. A. 72-81 and ___ F. Supp. ____. The opinion and order

of the court with respect to the merits of the proceeding—

which are not challenged in this appeal— are reported at A. 40-

68 and 304 F. Supp. 603 (E.D. La. 1969).

Appellees filed this action on February 4, 1966, on their

own behalf and as a class action on behalf of all other blacks

similarly situated alleging several violations of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§ 2000-e et seq. and the Civil

Rights Act of 1870, 42 U.S.C. 1981. The complaint alleged, inter

alia, that all three individual plaintiffs had been discharged

and refused reemployment solely on account of their race; that

defendant had been and was still engaged in a pattern of dis

criminatory hiring and promotional practices; and that restroom

and drinking facilities were segregated (A. 4-6).

Appellant, which operates a shipyard in the city of New

Orleans filed an answer denying the essential allegations of

the complaint (A. 11-12). There followed extensive pre-trial

discovery through numerous sets of interrogatories, depositions

and copying of company records. The matter was tried in January

1969 and on September 26 the court entered detailed findings of

fact and an opinion in which it found (A. 40-63):

1. That two of the three named plaintiffs had been

discharged on account of their race;

2. That the company followed a discriminatory

pattern in initial classification by classifying

2

unskilled whites as helpers and unskilled blacks

as laborers; that two lines of progression were

therefore formed; that unskilled whites had the

opportunity to progress to the best paying

jobs but unskilled blacks were limited

to particular low paying jobs;

3. That the company discriminated in its recruitment

policy since under such policy knowledge of

vacancies in better paying jobs was afforded

only to whites;

4. That the company discriminated in the provision

of instructional opportunities in that it pro

vided instruction in '■ tacking1'— a skill that was

vital to progressing to the best paying jobs—

to whites only.

On November 9, 1969, the court entered a comprehensive

order enjoining appellant from continuing to engage in the above

practices and requiring that the company undertake a number of

remedies to undo past discriminatory practices. The latter

included, .inter alia, an order that Turner and Magee be offered

reemployment with seniority credit; that no new or vacant

helper or tacker position be filled from outside the plant

until each black person then employed was given an opportunity

to bid for and transfer to such jobs; that transfers were to

be effected without decrease in the employee's hourly rate of

pay and without affecting his seniority rights or employment

benefits; and that training in particular jobs was to be

3

afforded blacks on the same basis as had been available to

whites (A. 64-68).

In his September 26, 1969, opinion, Judge Rubin had found

that plaintiffs— appellees here— were entitled to reasonable

attorneys' fees in accordance with Section 706(k) of Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k) In

an attempt to avoid the necessity for a formal hearing on fees

plaintiffs' attorneys prepared a proposed statement of fees

and costs which it forwarded to respondents by letter dated

December 1 1 , 1969. The fees were deliberately understated

with the hope that a quick agreement might be reached. The

offer was rejected outright by appellant (A. 116-117) and the

court fixed February 9, 1970, for a hearing on the proper

amount of the award. At the February 9, 1970, hearing attorneys

for plaintiffs filed itemizations of $27,130 in attorneys' fees

and $1,914.51 in costs for a total of $29,044.51 (A. 69-71).

At the hearing counsel for plaintiffs (appellees here)

introduced evidence as to the amount of hours spent and, by use

of an expert, the basis for the hourly rates included. The

company, appellant, was permitted to introduce into evidence—

!_/ Section 706 (k) provides:

(k) in any action

title the court, in it

the prevailing party,

or the United States,

fee as part of the cos

and the United States

the same as a private

or proceeding under this s discretion, may allow

other than the Commission a reasonable attorney's

ts, and the Commission

shall be liable for costs person.

4

compromise— the .statement of foes and coats transmitted

December 1 1 , 1969. which totaled $21,314.51 ($19,400 fees,

$1,914.51 costs (A. 131)).

Appellant attempted to introduce evidence which purportedly

would show that prior counsel for plaintiffs— not present

counsel who conducted the discovery and tried the case_had,

by unreasonable demands, blocked an early settlement of the

matter. The evidence was excluded by Judge Rubin at that time

(A. 165). Subsequently, however, he scheduled a new hearing

and on April 7, 1970, appellant was permitted to make an offer

of proof and to enter into the record any such evidence (A. 171-

188) .

On April 28, 1970, the court entered an opinion and order

awarding $20 ,000 in counsel fees and $1,914.51 in costs for a

total of $21,914.51 (A. 72-81).“ The allocation for fees was

substantially the same as that transmitted to appellant on

December 1 1 , 1970. This appeal is from that order.

S E S S T t S ^ S i . S S ? ? ! . A P P eU 6 e S S t i p U l a t e that P ^ e r

5

ARGUMENT

I.

Introduction

Appellant concedes, as it must, that an award of attorneys'

fees in suits under Title VII should be the rule rather than

the exception. Cf. Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprise*. 390

U.S. 400 (1968); Miller v. Amusement Park Enterprises. Inc..

---- F* 2d ---- (No. 27,529, 5th Cir., May 13, 1970). its only

argument is that special circumstances exist which require

that the fees awarded be disallowed totally or reduced. The

special circumstances to which it adverts may be summarized

as follows:

1. That no award should be made because some of the

attorneys for the plaintiffs were on the staff of

the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, Inc.;

2. That counsel for the plaintiffs blocked settle

ment by unreasonable demands; and

3. That the award by the court is too high because

lawyer time was exaggerated by plaintiffs-

appellees and because plaintiffs' counsel were

not "veteran attorneys."

Each of these points will be shown to have no basis in fact or

law.

6

II.

gounaojLFce__ Awards to Successful Plaintiffs

"f ,Tltle " -1' Acti°ns May Not "Be Denied,TIm^ j^ed °r Otherwise Reduced Because Some n r ~ n

£f Tneir counsel Were .Affiliated' with a t.^TT

Aid Organization. ------**—

Plaintiffs below were represented in this action by A. M.

Trudeau and Lolis Elie, members of the Louisiana bar and pri

vate practitioners, and by Robert Belton and Franklin E.

White, members of the New York bar, practicing with the NAACP

Legal Defense and Education Fund, InC. and admitted pro hac

vice. Mr. Elie and Mr. White assumed major responsibility for

the case after its initial stages in 1966.

Appellant contends that Judge Rubin's award should be

overturned or reduced because Mr. Belton and Mr. White were

salaried employees of the Fund and because of the possibility

that the Fund might share in the award. As authority for this

proposition they rely on dicta in Dobbins v. Electrical Workers

jlBEW) Local 212, 61 L.C. 19327 (S.D. Ohio 1969), that ''[i]f

the plaintiff is bound by a contract of 'dispositions' [of

attorneys' fees] to a non-licensed recipient, this Court would

hold the fact to be a 'special circumstance' that would render

the award unjust (to any such extent)." 61 L.C. 59328.

But the "non-licensed recipient" referred to in Dobbins

was the National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People, which, the court noted, holds no license to practice law

as an organization, but which had furnished the services of one

of its New York employees in prosecuting the case. The situation

7

here is much different. The organizational assistance rendered

local counsel in this case was not from the NAACP but from the

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., a completely

separate, individually chartered, charitable, non-membership,

legal organization dedicated to the protection of the rights

of blacks and other minorities through the judicial process.

It employs only lawyers and clericals. It is, in effect, a

civil rights law firm, composed of 25 attorneys licensed to

practice law. its charter was approved by a New York State

Court, authorizing the organization to serve as a legal aid

society. Quite clearly the Legal Defense Fund falls outside

the Dobbins definition of a "non-licensed recipient." And there

is no reason why it should not share in fees in the same manner

as with other law firms.

There are, however, much more important reasons, some

touching the long-term viability of the Act,which require that

the limitation suggested in Dobbins and advocated by appellant,

be rejected.

The statutory grant of counsel fees in civil rights cases

goes beyond the purpose of such awards as part of the court's

general equity power to make an individual plaintiff whole.

The United States Supreme Court articulated in Newman v. Pigqie

— Enterprises, supra, the Congressional intent that an indi

vidual prevailing in such a suit "does so not for himself alone

8

but also as a 'private attorney general,• vindicating a policy

that Congress considered of the highest priority." 390 U.S.

400, 402 (1968).

The legislative history of Title VII and the radical

changes that occurred in this title in the course of its legis

lative process make clear the fact that Congress intended this

result in Title VII suits as well.

As originally presented to Congress and passed by the

House, the enforcement procedures of Title VII were similar to

those in the National Labor Relations Act and would have estab

lished a powerful commission similar to the National Labor

Relations Board.

Not only would the commission have power to investigate and

conciliate, but it would have the right to go to court where

voluntary compliance was unsuccessful. Private persons were

not permitted to file civil actions except in limited circum

stances, and then only with the approval of the commission.^

As finally enacted, however, Title VII placed enforcement

in the federal courts rather than an administrative agency. As

such the enforcement of the Act was turned "inside out" and it

is left primarily to the aggrieved person to enforce his right

in a civil action. See Johnson v. Seaboard Airline Railroad Co..

405 F.2d 645 (4th Cir. 1968). To the extent that universal

voluntary compliance was not achieved, Congress saw widespread

1 st slss?1a 9 6 3 K htS 8 1 1 1 °f 1963, H-R- 7152' 88th Cong-'

9

use of the courts to insure elimination of discrimination in

employment

Congress attempted to cushion the impact of altering

Title VII enforcement from administrative procedures to requir

ing private judicial initiative, by specifically providing for

the allowance of attorney's fee. As the Supreme Court stated

in Newman v. Piggie Par*., supra, "It was evident that enforce

ment would prove difficult and the nation would have to rely

in part upon private litigation as a means of securing broad

compliance with the law."

An assurance that counsel's fee would be available to a

prevailing party necessarily would encourage private attorneys

to take on this burden. The attorney fee provision is there

fore a key feature in rendering Title VII enforcement procedures

workable. The cases also recognize this principle. Jenkins v.

United Gas, 400 F.2d 28 (5th cir. 1968), states, for example

that in such cases "the individual, often obscure, takes on the

mantle of the sovereign." Thus counsel fees have been awarded

in the numerous Title VII cases: Quarles v, Philip Morris m e

279 F. Supp. 505 (E.D. Va. 1968); Dobbins v. IBEW. Local 217

292 F. Supp. 413 (S.D. Ohio 1968): United states v. Local 189-

UPP. 301 F. Supp. 906, 60 CCH Lab. Cas. , 9247 (E.D. La. 1969);

Bowe v. Colgate, 272 F. Supp. 332 (S.D. Ind. 1967), reversed in

part on other grounds, ___ F.2d ___, 61 CCH Lab. Cas. , 9326

(7th Cir. 1969): Cheatwood v. South Central Bell Telephone

Telegraph Company, --- F. Supp. ___, 60 CCH Lab. Cas. g 9299

T5thS“ rfe" & S j'.V - United na" CSffiSBtiSn. 400 F.2d 28. „. 1

10

(M.D. Ala. 1969); Richards v. Griffith Rubber Mills. 300 F.

Supp. 338 (D. Ore. 1969) (attorneys' fees although no relief

issued; Garner v. E. I. duPont, 60 CCH Lab. Cas. * 9300 (W.D.

Ky. 1969); Petway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co.. 411 F.2d 998

(5th Cir. 1969); Carter v. Hoit-Williamson Mfa. Cn.. 62 CCH

Lab. Cas. H 9436 (E.D. N.C. 1969); Long v. Georgia Kraft Co..

62 CCH Lab. Cas. I 9437 (N.D. Ga. 1970); Culpepper v.

Metals Co., No. 12,179 (N.D. Ga., August 13, 1970); Broussard

V- Sehlumberger Well Services. No. 68-H-215 (s.D. Texas, Aug. 4,

1970); £P£99is v- United Airlines, Inc.. 308 F. Supp. 959 (N.D.

111. 1970).

Class action Title VII cases are time-consuming and expen

sive. They require months, sometimes years, of pretrial discovery.

Analyzing the wealth of data likely to be produced, weaving them

into a coherent presentation and dealing with the many proce

dural hurdles encountered in such cases require massive inputs

of time and money which no private practitioner can sustain.

But black people cannot afford to begin to pay the fees neces

sary to maintain the practitioner during the course of litigation.

Thus local attorneys, who enter such cases on a contingent fee

basis, must look to a legal aid kind of institution for finan

cial and technical assistance along the way. The record in this

case is as good an example as any of a matter no private practi

tioner could himself have maintained on a contingency fee basis.

If, as a practical matter, the only way Title VII cases can

be brought is with the assistance of an organization such as

the Legal Defense Fund, it is altogether fitting that the time

11

of both the local lawyer and the organization's lawyers be cotn-

5/

pensated in making the award. To diminish the award here

because of the participation of its lawyers would be to grant the

defendant a windfall at the expense of the public whose contribu

tions make the work of the Legal Defense Fund possible. The

financial burden should rightly be borne by those whose intransi

gence and wrongdoing made the litigation necessary. Rather than

diminish such fees, the court should be vigilant to insure their

fairness so as to encourage such organizations to lend their

assistance in areas where Congress has required individuals injured

by racial discrimination to seek judicial relief, where the need

for free legal services is well recognized, and where these organ

izations vindicate policies deemed by Congress to be of the highest

priority. Cf. Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises, supra; Jenkins

v. United Gas Corp., 400 F.2d 28, 32 (5th Cir. 1968).

There is nothing in the legislative history of the 1964 Act

which suggests that awards were to be diminished or precluded

where a legal organization participated as counsel. Indeed, the

legislative history of a similar provision in the Fair Housing Act

of 1968 plainly suggests that no such limitation was intended in

provisions of that kind. In the debate concerning the provision

for attorneys' fees in the Fair Housing Act of 1968, United Scates

Senator Hart, floor manager of the bill, noted the critical

importance of the contributions of such legal representation:

5/ it should be noted that L.D.F. would recoup only a fraction of

the expenses actually incurred in litigating this case. No request

was made, for example, for air fare to New Orleans, hotel bil^s

and other expenses incurred in assisting in this matter.

12

Frequently indigent plaintiffs are represented

by legal associations, acting as "private attor

neys general" in the vindication of important

constitutional and statutorily created rights.

It would be most anomalous if courts were per

mitted to deny these costs, fees, and damages

to an obviously indigent plaintiff, simply

because he was represented by a legal associa

tion. I think it should be clearly understood

that this representation in no way limits a

plaintiff's right of recovery. 114 Cong Rec § 2308.

The court in Dobbins impliedly recognized this factor in changing

its earlier ruling (limiting recovery to costs incurred before

the attorney general entered the suit) to cover the costs over

the entire period of litigation.

There is no difference in principle between the attorneys'

fees provisions of the 1968 and 1964 Acts. It is apparent that

under the 1968 Act licensed legal association such as the Legal

Defense Fund are entitled to counsel fees. The same should be

true of Title VII under which litigation is more difficult and

which vindicates rights more critical to the long term social

health of the nation.

In Miller v. Amusement Park Enterprises, Inc.. ___ F.2d

--- (No. 27529, May 13, 1970), this Court appears to have

reached that conclusion. And although no explicit ruling was

made, the plain effect of the decision was to require that fees

be awarded for services rendered by organizational lawyers.

There, plaintiffs represented by local counsel and Legal Defense

Fund lawyers secured from this Court a ruling that the amusement

park in question was covered by Title II. On remand, the dis

trict court denied counsel fees on the ground that there were

special circumstances warranting its disallowance. On appeal,

prosecuted by Fund lawyers, the park contended, inter alia, that

13

Ui»> denial oI loon wa.4 proper since no fees were collected by

the organization which was counsel for plaintiffs and there

was no obligation on the part of the plaintiffs to pay. The

argument was rejected, the judgment was reversed, and the

district court ordered to award reasonable counsel fees without

6/

any limitation. Said the court (slip op. 9-10):

What is required is not an obligation to pay

attorney fees. Rather what--and all — that is

required is the existence of a relationship

of attorney and client. ... Any other approach

would call either for a fictional formal agree

ment by persons legislatively recognized as

frequently unable to pay for such services ...

or a frustration of the Congressional scheme

to effectuate the policies of the Act through

private suits in which, of course, an attorney

is a practical necessity. Congress did not

intend the vindication of statutorily guaran

teed rights would depend on the rare likelihood

of economic resources in the private party (or

class members) or the availability of legal

assistance from charity— individual, collective.

or organized.(Emphasis supplied.)

The district court in this case made a similar finding

stating:

The statute [Title VII] does not prescribe the

payment of fees to the lawyers. It allows the

award to be made to the prevailing party.

Whether or not he agreed to pay a fee and in

what amount is not decisive ... The criteria

for the court is not what the parties agreed

but what is reasonable ... [Congress] did not

look, like Lear's jester, to the breath of the

6/ The court observed that (slip op. 9, note 14):

Included among counsel were attorneys asso-

ci-ated with a legal defense group who have

acted in hundreds of civil rights cases before

this court and the District Courts of this Circuit.

The reference is to the NAACP Legal Defense Fund.

14

imfee d lawyer, but considered that the pre

vailing litigant should be able to pay the

laborer the worth of his hire.

(Mem. Opinion of April 24, 1970; A. 75-76.)

A denial or reduction of counsel fees in this case because

of the participation of lawyers from the NAACP Legal Defense

Fund, Inc. would result in what this Court has said Congress

did not intend: That is, that vindication of statutory rights

will depend on the rarity of a black person or class able to

pay legal fees or the availability of free legal aid. Even

where free legal service is available, denial of fees will

unjustly enrich precisely the class that Congress determined

should pay the cost of the litigation. Most importantly, it

will seriously hamper the long-term enforcement of Title VII

and therefore frustrate the nation’s drive toward equal employ

ment opportunity.

III.

Appellees' Attorneys' Efforts to Settle

This Case Without Litigation Were Earnest

.?nd Reasonable and Were Unsuccessful Due

Only to the Disinterest of Appellant i ~

Further Settlement Negotiation-:--------

Defendant (appellant here) contends that litigation of

this case could have been avoided but for plaintiffs' action

of placing impossible conditions in compromise discussions.

(Appellant's Brief, pp. 8-9.) The record, however, points to

an entirely different, and contradictory conclusion.

Conciliation efforts began in May, 1966. On May 20, 1966

a conciliation meeting was held between attorneys for plaintiffs

15

defendant and the Equal Employment Opportunities Commission.

On June 7, 1966, defendant sent a draft settlement agreement

to EEOC. On June 16, 1966, plaintiffs moved in the district

court for a stay of further proceedings pending conclusion of

conciliation procedures with EEOC. On August 31, 1966, a

further meeting was held between the parties to negotiate settle

ment. On September 20, 1966, plaintiffs' attorneys sent defendant

a draft proposal for settlement. On September 28, 1966,

defendant responded objecting to certain provisions of the

draft (A. 177-199). On October 11, 1966, plaintiffs' attorneys

responded to the defendant's letter of September 28, 1966,

suggesting that further consideration be given to the areas of

disagreement, and suggesting a meeting in Washington at the

headquarters of EEOC to negotiate further (A. 199-202). Defendant

never responded to this invitation. Thus, it was as a direct

result of defendant's inaction that negotiations ended at that

point (A. 203, 183-184).

Defendant's contention that the plaintiffs’ proposed

conciliation agreement made impossible demands is clearly ten

uous. The relief afforded by the court required far greater

efforts of the defendant to correct past discriminatory prac

tices than that originally demanded by the plaintiffs in their

draft settlement agreement. Compare A. 64-69 with A. 199-202.

The fact that the court did not require reports to counsel for

plaintiffs is a result of the court's assumption of jurisdic

tion.. because settlement was not reached between the parties.

Changes in toilet and locker facilities was clearly a minor demand

16

compared with points one and five of plaintiffs' draft, which

the district court granted in its final order (A. 64-69).

In any event, defendant fails to explain why, if it

thought plaintiffs were being unreasonable, it made no effort

to secure the assistance of the trial judge in resolving the

dispute. And this is all the more curious since the matter

of locker room and toilets were never discussed after Judge

Rubin entered the case. it was, by December 1967— more than

one year later and when discovery procedures were initiated_

no longer an issue. it was not mentioned in the pre-trial order

setting forth the issues nor was it discussed at the trial. To

claim at this point that disagreement over toilet facilities

blocked settlement of this matter is patently absurd.

The last effort to settle the case was plaintiffs' attor

neys letter of October 11, 1966, which was consciously ignored

by defendant (A. 180, 183-184). Between that time and the time

of trial on January 22, 1969, numerous pre-trial conferences

were held. On no occasion did the defendant raise the possi

bility of further settlement negotiation, although plaintiffs

indicated to the court that they were willing to hold such con

versations at any time (A. 186).

Judge Rubin, at the close of the April 7, 1970, hearing

observed:

In this case, the Court repeatedly inquired

of counsel for the defendants as well as of

counsel for the plaintiffs whether any discus

sion of settlement would be fruitful, [sic] although

the Court did not keep minutes of these con

ferences, indeed does not ever keep minutes of

17

informal conferences because to do so would

disrupt the informality that the Court strives to achieve, [sic]

The Court was repeatedly told by counsel for

the plaintiffs that they were willing to cFTK̂ —

cuss compromise and was told on several occa

sions by counsel for the defendants~~tKat----

discussions of compromise were not being

fruitful, and the Court following its usual

policy, did not pursue the matter further

because the Court didn't feel that it ought to

tell the defendant in this kind of suit that

it had to talk settlement.

This Court's familiarity of the matter stems

from the time sometime in 1967 when the case

was reassigned, but in reflecting on the matter

and running through the record, I find that the

first of a number of conferences was held on

December 21, 1967, another conference was held

on February 21, 1967, at which I am certain

this matter was brought up because the pretrial

order then entered says it was, another confer

ence was held on July 2, 1968, at which the

matter was again brought up, another conference

was held on November 15, 1968, and without in

any way reflecting on the decision in this case,

xt just seems to me that if counsel for either

party is serious and desires to discuas any

possibility of settlement, ample opportunity

was afforded during this period of time without

.gggard to what may have happened before. (A. 186-

187) (Emphasis supplied.)

Whether counsel fees should be denied or limited because

the successful litigant had unfairly impeded settlement is

obviously a matter with the discretion of the trial judge. It

is clear that this matter was carefully considered by Judge

Rubin and there is nothing in the record which suggests that

1_/

he abused his discretion in that regard.

2/ Defendant's suggestion "that plaintiffs' attorneys bear

the responsibility for the time, at least in substantial part,

they spent in this litigation" (Appellant's Brief, p. 9), is

clearly inappropriate. in addition to the defendant's failure

18

IV.

The Plaintiffs' Estimate of Time and

Value of Their Services Were Reason

able in the Circumstances of This Case.

Defendant asserts that the amount of plaintiffs' claim

ought to be reduced because they did not prevail in every aspect

8/

of their case. Plaintiffs were able, in fact, to sustain

almost all of their allegations. The court found discrimination,

as alleged, against two of the three plaintiffs, as well as

against the class. More importantly, the court found and orders

terminated a generalized pattern of insidious multifaceted dis

crimination, proof of which was time-consuming and difficult to

adduce. (A. 28-63; compare, e.g., plaintiffs' exhibits at A.

189-198, the extensive proposed findings of facts and the numer

ous memoranda of law.)

In any event, it should be noted that a victory for the

individual plaintiff is not a prerequisite to an award of attor

neys' fees. See Richard v. Griffith Rubber Mills. 300 F. Supp.

388 (D. Ore. 1969), where attorneys' fees were awarded although

(Continued)

to accept plaintiffs' invitation for further negotiation for set

tlement, the record shows that the defendant applied for and was

granted extensions of time for filing virtually every pleading

in this case, including the answer to the complaint, answersto

all three sets of interrogatories propounded by plaintiffs',

defendants’ proposed findings of fact, post-trial brief, and brief

on appeal. Defendant must thus bear responsibility for any delav

in the resolution of this cause of action, not plaintiffs.

®/ Defendant's allegation that fees should be reduced because

some of the objections to the initial set of interrogatories

were sustained, hardly merits refutation. Indeed, virtually all

the interrogatories propounded by plaintiffs were required to be

answered and this was true of the first set also. Compare the

three sets of interrogatories and the answers thereto which are

a part of the original record filed in this case.

19

no relief was issued for the particular plaintiff. Compare

Jenkins v. United Gas Corp.. 400 F.2d 28, 32 (5th Cir. 1968).

Defendant argues that counsel fees ought to be reduced on

a number of other grounds which are both factually inaccurate

and frivolous, i.e., that no compensation should be granted for

the presence of more than one lawyer at any hearing; that a

law student was used whose hours were reported; that the rates

charged were too high in that the attorneys for plaintiffs were

not "veteran lawyers;" that the itemization submitted in court

on February 9, 1970, was different from that transmitted to

counsel on December 11, 1970; and that no allowance was made for

the newness of the law.

Duplication of Counsel.

None of the items submitted (A. 69) included the hours for

more than two counsel even where additional counsel appeared.

Thus, for example, although Mr. Trudeau attended part of the

in January, 1970, the 32 hours submitted represented only

Mr. White and Mr. Elie's time (A. 70). The court noted the

, . 9/complexity of the trial and of all the aspects of this case.

Both Mr. Elie and Mr. White actively participated at the trial.

9/ In his April 24 opinion on fees. Judge Rubin observed:

The issues required considerable skill to

present, and the actual trial was relatively

short only because, as a result of many pre

trial conferences and elaborate pretrial

preparation, plaintiffs' counsel marshalled

an impressive array of facts, skillfully ana

lyzed them, and presented them lucidly. In

less capable hands or with less preparation, the

trial could well have lasted weeks. (A. 79;

compare A. 168.)

20

The participation of both counsel in view of the heavy input

was clearly warranted and necessary to provide adequate repre

sentation to the plaintiffs.

Law Student Hours.

It was fully explained at the hearing that "none” of the

law student’s time was included in the submission and that the

120 hours in item "N" (preparation of exhibits) (A. 100) was

fully Mr. White's time. if counsel for defendant doubted Mr

understanding and appreciation of the exhibits he was obligated

to make that clear by cross-examination and not by his undocu

mented "suggestion" in a brief on appeal.

"Veteran" Attorneys.

Appellant suggests that the fee be tied to length of

practice rather than the difficulty of the issues and the

quality of the representation. The proposition hardly needs

extensive rebuttal. For, as this Court knows, legal ability

does not necessarily increase proportionately with years of

practice. A better determinant of a reasonable fee is the qual

ity of the legal product which, in this case, amply justifies

the award.

The district court noted that the case involved interpre

tation of a new and difficult statute, and that the case was

filed before many of the decisions cited in the court's eventual

opinion had been reached (A. 78). On more than one occasion it

complimented the work of plaintiffs' c o u n s e l . i t said

(A. 169-170):

10/ See note 9, supra.

21

The material filed in this case ... was, I

think, far, far above average and indeed

ranks with the best material that I have had

to consider in any case in the three years I

have sat on the bench ... [i]t would be unfair

to assume that he who does bad work is entitled

to the same pay as he who does good work.

In any event, Mr. Elie and Mr. White have been members of

the bar for some eleven and five years, respectively. Certainly

the award is not excessive given the complexity of the legal

issues, the enormous time input and exceptionally high quality

of their efforts.

Dj-ffer:*-nc* Estimate of Attorneys' Fees between

December 11, 1969, and February 9, 1970.

The letter of December 11, 1969, appended by appellant to

its brief (Brief pp. 14-17) was simply an offer by plaintiffs'

counsel in the hope that the matter could be resolved without

the necessity of a formal hearing. it was rejected. The pro

posal was made at the express direction of the trial court.”

Since it was an offer of compromise it, of course, differed from

plaintiffs' formal submission at the hearing. Except, however,

for the hourly rates, the differences were minor.

The December 11, 1969, proposal, since it stemmed from an

attempt at compromise, should not, in our view, have been

admitted. in any event, that there were differences between

11/ Judge Rubin observed during the hearing:

I will say for the record that I urge both

counsel to try to get together and see if they

can reach an agreement with respect to counsel

fees, and I told them I stood ready to hear the

matter if they could not. (A. 116)

22

the amounts requested is not helpful to appellant. For, the

fee ultimately awarded by the court differed by only $660 from

the December proposal whereas the later request was $7,730

higher. it should be noticed also that neither proposal

included the time spent in preparing for and attending the

two hearings on fees.

Summary:

Judge Rubin's April 28 opinion reflects that in making

the determination of a reasonable fee he very carefully weigi

factors, including those recommended by the American Bar

Association.

No extensive reply need be made to appellant's claim that

plaintiffs' itemization exaggerated hours spent and requested

an unduly high hourly rate. Judge Rubin’s award was of a

total sum. No one cay say precisely, therefore, how many hours

he accepted or rejected, what hourly rate he used, nor whether

that rate was different for the various items. It seems apparent

however, that the overall rate was not appreciably more than

the $30.00 per hour recommended by the Louisiana State Bar

Association and, indeed, appellant had fared much better than

it thinks for the ultimate award was $7,700— roughly one-four_

less than plaintiffs had requested.

Obviously the trial court is the best judge of the quality

of plaintiffs' efforts and of how much time—input would reasonably

12/ Appellant claims that newness of the law is a special cir

cumstance requiring disallowance or limitation of the fee. That

argument has already been rejected in Miller v. Amusement Park

Enterprises, Inc., supra, at 6 , n. 5; 8-9.

23

have been required along the way. We suggest that this Court

conduct a very careful review of the record in this case,

including the extensive interrogatories, records copied and

analyzed, exhibits, proposed findings of fact and the numerous

pre and post-trial briefs. That review would demonstrate that

the $20,000 awarded was moderate and conservative, especially

in light of the accepted practice that hourly rates may properly

be higher in contingency fee cases.

V.

The District Court Did Not, on This Record.

Abuse Its Discretion by Allowing CosTiT

Appellant contends that the additional costs submitted,

apart from attorneys1 fees, should not be assessed because they

were not discussed at the February 9 hearing. But plaintiffs-

submissions in December and February made it plain that they

were seeking recovery for costs as well as fees. And each

item sought to be recovered as costs was proper under 28 U.S.C.

§ 1920 and was separately stated (A. 70; Appellant's Brief, p.

17). Those itemizations served in practical effect as a bill

of costs under § 1920.

Rule 54, F.R.C.P. provides that "costs shall be allowed

as of course to the prevailing party." it has been suggested

that a denial of costs is proper only:

13/ Substantial counsel fees, exceeding $20,000, were awarded,

fErneXTaPl?Qfio? ^ ted States v. Local 189. 301 F. Supp. 906

reached ^ ^ K ^ gree?ent f°r 3 similarly large amount was

279 F su^p ^ PhUiP Mogri"' Tnr~-

24

In the nature of a penalty for some defection

... in the course of the litigation as, for

example, by calling unnecessary witnesses,

bringing in unnecessary issues or otherwise

encumbering the record, or by delaying in

raising objections fatal to the plaintiff's

case. Chicago Sugar Co. v. American Sugar Co.,

176 F.2d 1, 11 (7th Cir. 1949).

No such allegations have been made here and none can be asserted

in good faith.

The rule permits costs to be taxed by the clerk and where

the latter's action is challenged resort be made to the court.

Here plaintiffs were already before the court with respect to

fees. It was logical and simple to make its request for costs

at that time.

Appellant was not prejudiced by plaintiff's failure to file

a document titled "Bill of Costs" or by the fact that the court

acted in the first instance rather than the clerk. For, as

previously indicated, it was fully aware of the request for

allowance of costs which were clearly itemized. Yet, it chose

not to contest them, although it had an adequate opportunity to

do so at either the February 9 or April 7 hearings. The specific

approval by the court in its April 28 order clearly cured any

defect that may have theretofore attached by the failure to

file initially with the clerk.

Whether costs ought to be taxed is plainly a matter for

the discretion of the trial court. Appellant made precisely

this argument after the hearings below and they were rejected by

25

14/

Judge Rubin. There is nothing in its brief which

that in awarding costs he had abused his discretion.

indicates

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the court should affirm the

district court's grant in toto of plaintiffs' claim for attor

neys fees and costs in this case so that such "private

attorneys generals" will not be penalized for performing the

public function of eradicating unlawful discrimination in

employment.

Respectfully submitted,

S E. E L I E ---

om 1 1 1 0

344 Camp Street

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

A. M. TRUDEAU

1821 Orleans Avenue

New Orleans, Louisiana 70146

ROBERT BELTON

216 West 10th Street

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

JACK GREENBERG

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

FRANKLIN E. WHITE

SYLVIA DREW

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Plaintiffs-Appelleeu

14/ There is no claim by appellant that any item of cost is

exaggerated. Virtually all the amounts are verifiable froi

the very record in the case. And as to propriety thlir allow-

liltsL f f P RUbln- defPite these ^ arguments below, indi-' lach item consciously exercised his discretion to permit

26

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

The undersigned certifies that copies of the foregoing

Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellees were served by United States

mail, air mail, postage prepaid, this 11th day of September,

1970, as follows:

Samuel Lang, Esq.

Richard C. Keenan, Esq.

Kullman, Lang, Keenan, Inman & Bee

1010 Whitney Building

New Orleans, Louisiana 70130

Stanley Herbert, Esq.

General Counsel

Marian Halley, Esq.

Equal Employment Opportunities Commission

1800 G Street, N.W.

Washington, D. C.

27

r