United States v. Mississippi Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 23, 1986

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Mississippi Brief for Appellants, 1986. 0665218e-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/57f23ac9-41c2-40ca-b941-15b56452a7da/united-states-v-mississippi-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

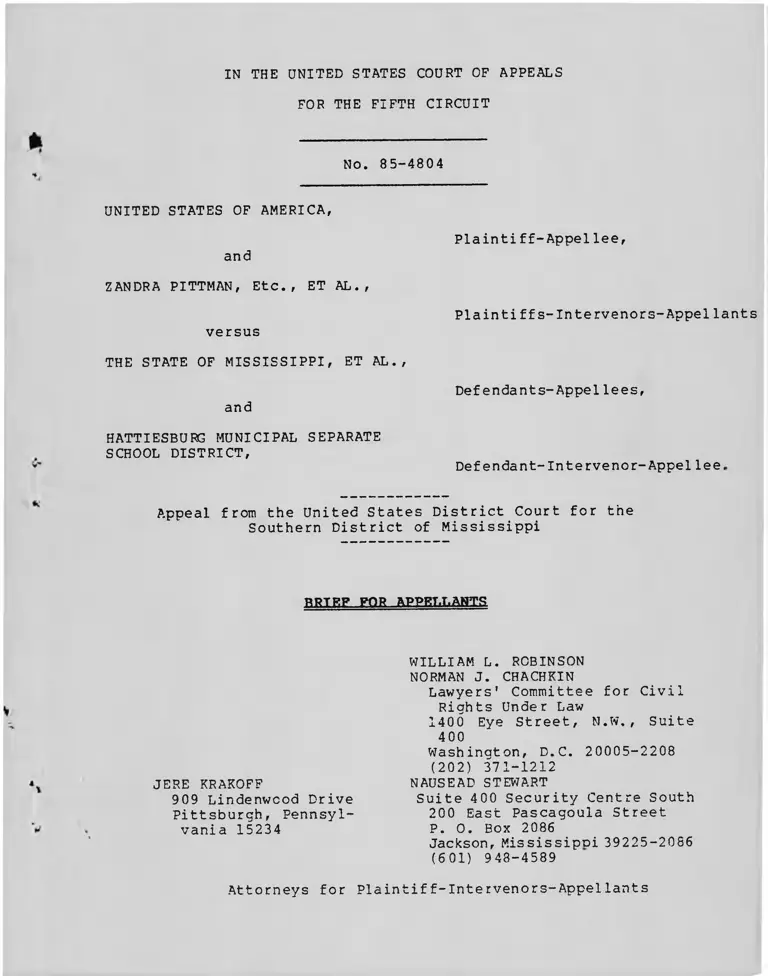

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 85-4804

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

and

ZANDRA PITTMAN, Etc., ET AL.,

versus

THE STATE OF MISSISSIPPI, ET AL.,

and

HATTIESBURG MUNICIPAL SEPARATE

SCHOOL DISTRICT,

PIainti ff-Appel lee.

Plaintiffs-Interveners-Appellants

Defendants-Appel lees.

Defendant-Intervenor-Appellee.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Mississippi

BRTRP FOR APPELLANTS

JERE KRAKOFF

909 Lindenwcod Drive

Pittsburgh, Pennsyl

vania 15234

WILLIAM L. ROBINSON

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

Lawyers’ Committee for Civil

Rights Under Law

1400 Eye Street, N.W,, Suite

400

Washington, D.C. 20005-2208

(202) 371-1212

NAUSEAD STEWART

Suite 400 Security Centre South

200 East Pascagoula Street

P. 0. Box 2086

Jackson, Mississipoi 39225-2086

(601) 948-4589

Attorneys for Plaintiff-Intervenors-Appellants

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 85-4804

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

and

ZANDRA PITTMAN, Etc., ET AL.,

versus

THE STATE OF MISSISSIPPI, ET AL.,

and

HATTIESBURG MUNICIPAL SEPARATE

SCHOOL DISTRICT,

Plaintiff-Appellee.

Plaintiffs-Intervenors-Appellants

Defendants-Appellees.

Defendant-Intervenor-Appel lee.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Mississippi

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

The undersigned counsel of record certifies that the following

listed persons and bodies have an interest in the outcome of this

case. These representations are made in order that the Judges

of this Court may evaluate possible disqualification or recusal.

The United States of America

Zandra Pittman, a minor child and her parents,

Andrew Pittman and Patricia Pittman

Geneva Harrell and Jimmy Harrell, Jr., minor

children, and their parents, Jimmy Harrell

and Rose Mary Harrell

- 1 -

The class of all students attending the public schools of the Hattiesburg Municipal Separate

School District

The State of MississippiThe Mississippi State Board of Education and

its members, Joe Blount, Carolyn Gwin, Arthur

Peyton, Talmadge Portis, James E. Price,

Jr., Jack Reed, Sr., Lucimarian Roberts,

Joe M. Ross, Jr., and Tommy WebbRichard A. Boyd, Mississippi Superintendent

of EducationThe Mississippi State Educational Finance

Commission and its members, J.W. Collins,

J. Tom Dullin, J.Y. Trice, W.L. Roach, J.W.

Phillips, and Boyce ColemanFrank I. Lovell, Jr., Executive Secretary of

the Mississippi State Educational Finance

Commission

The Hattiesburg Municipal Separate School

DistrictGordon Walker, Superintendent of the Hatties

burg Municipal Separate School District

The Board of Trustees of the Hattiesburg Muni

cipal Separate School District and its members, F. Charles Phillips, Paul W. McMullan,

Andrew Wilson, Harry McArthur, and Dr. Char

lotte Tullos

January 23 , 1986

NORMAN J. CHACHKIN

Attorney for Plaintiff-

In tervenors-Appel lants

- 1 1 -

Request for Oral Argument

Appellants respectfully request that oral arguinent be sched

uled in this case because of the great public importance of the

subject matter (school desegregation) and of the major ground

advanced by the court below in support of its decision (anticipated

"white flight" if a school pairing plan were implemented.)

While this Court has consistently and recently rejected "white

flight" as a justification for adopting a desegregation plan which

is less promising than available alternatives, the failure of

the district court to follow that well-established precedent (when

urged by the United States that it need not do so) suggests the

critical importance of reaffirming the governing legal principles

in this matter.

Oral argument will also provide an opportunity for the Court

to have any factual ambiguities or questions which may arise on

the record or in the briefs clarified; school desegregation cases

are highly fact-intensive and the plan approved below encompasses

a number of varying activities at different schools.

- Ill -

TART.R OF CONTENTS

Certificate of Interested Persons . . . .

Request for Oral Argument............ .

Table of Contents.................... .

Table of Authorities................ .

Statement of Jurisdiction ............ .

Statement of Issues Presented for Review

Statement of the Case

1. Proceedings Below ............

2. Statement of Facts ..........

a. The Hattiesburg district .

b. The magnet p l a n ........

c. The Stolee plan ........

d. Effectiveness of the plans and

"white flight" ..............

Summary of the Argument

ARGUMENT —

Introduction .

Page

i

iii

iv

vi

1

II

The Plan Approved Below Is Constitutionally

Inadequate Because It Does Not Reach

Racially Isolated Schools Which Can Rea

sonably And Feasibly Be Desegregated . . .

The Plan Approved Below Impermissibly

Postpones Desegregation of Hattiesburg's

Elementary Schools for Years ............

2

6

8

10

15

18

23

26

28

35

*A note concerning the form of citations to record

materials appears at the end of the Table of Contents

- IV -

Table of Contents (continued)

Page

Argument (continued)

III Anticipated White Flight Cannot Justify

Adoption Of The Less Effective Magnet

School Desegregation Plan ..............

IV Magnet Schools And Educational Improve

ments Should Be Implemented In Conjunction

With A Mandatory Desegregation Plan . . .

Conclusion .......................................

Appendix .........................................

Certificate of Service

39

46

49

la

*Throughout this brief, record materials are cited as follows:

The consecutively paginated two volumes of original papers

assembled by the district court clerk (Vol. 1 and 2 of the Record

on Appeal) as "R. __

The consecutively paginated four-volume Transcript of Hearing

held October 1-4, 1985 in Hattiesburg (Vol. 4-7 of the Record on

Appeal) as "Tr. __

The single volume of proceedings on the motion to intervene

held before the district court on July 26, 1984 (Vol. 3 of the

Record on Appeal) as "R. Vol. 3 p. __."

The Docket Entries (appearing at the front of Vol. 1 of the

Record on Appeal but separately paginated) as "Dkt. Ent. p. -- ."

Exhibits introduced at the October 1-4 hearing by the United

States government as "G-X __by the defendant-intervenor Hat

tiesburg Municipal Separate School District as "D-X __and by

the plaintiff-intervenors (appellants) as "PI-X __ ." (All ex

hibits were admitted without objection, Tr. 13.)

The Memorandum Opinion and Order from which this appeal is

taken as "Mem. Op. __."

Material included in the separately bound and paginated Record

Excerpts as "R.Exc. __."

- V -

Table of Authorities

Page

Cases t

Acree v. County Bd. of Educ., 4

Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U

Adams V. Mathews, 403 F.2d 181

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd.

19 (1969) ..............Allen V. Board of Pub. Instruct

County, 432 F.2d 362 (5th

denied, 402 U.S. 952 (1971

Arthur V. Nyquist, 514 F. Supp.

aff'd mem., 661 F.2d 907 (

denied sub nom. Griffin v.

1085 (1981) ............

Arthur V. Nyquist, 473 F. Supp.

1979) ..................

58 F.2d 486 (5th

.S. 1006 (1972)

(5th Cir. 1968)

of Educ., 396 U.S,

ion of Broward

Cir. 197 0) , cert.

) .........................1133 (W.D.N.Y.),

2d Cir.), cert.

Arthur, 454 U.S.

830 (W.D.N.Y.

Berry v. School Dist. of Benton Harbor, 515 F.

Supp. 344 (W.D. Mich. 1981), aff'd and re

manded, 698 F.2d 813 (6th Cir.), cert, de

nied, 464 U.S. 892 ( 1 9 8 3 ) ..............

Brown V. Board of Educ. of Bessemer, 464 F.2d

382 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 981

(197 2 ) ...................................Brunson v. Board of Trustees, 429 F.2d 820 (4th

Cir. 197 0 ) ...............................

Carr v. Montgomery County Bd. of Educ., 429 F.2d

382 (5th Cir. 197 0) ......................Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd., 396

U.S. 290 (197 0) .................. .. . . .

Cisneros v. Corpus Christi Indep. School Dist.,

467 F.2d 142 (5th Cir. 1972) (en banc), cert,

denied, 413 U.S. 920 (1973) ..............

Davis V. Board of School Comm'rs of Mobile, 402

U.S. 33 (1971)...........................Davis V. East Baton Rouge Parish School Bd.,

721 F.2d 1425 (5th Cir. 1983) ..........

Davis V. East Baton Rouge Parish School Bd.,

514 F. Supp. 869 (E.D. La. 1981) ........

Ellis V. Board of Pub. Instruction of Orange Coun

ty, 465 F.2d 878 (5th Cir. 1972), cert, de

nied, 410 U.S. 966 ( 1 9 7 3 ) ................

16n

35n

25, 34, 35n

16n

37n

37n

Flax V. Potts, 464 F.2d 865 (5th Cir.), cert, de

nied, 409 U.S. 1007 (1972)................

47 n

29n

4 On

7n

25, 34, 35n

16n

25, 32n-33n

passim

15n

33n

8n

- VI -

Page

Cases (continued):

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968) ........................ 35n

Hall V. St. Helena Parish School Bd., 417 F.2d

801 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 396 U.S. 904

(1969)....................................... 35n

Harrington v. Colquitt County Bd. of Educ., 460

F.2d 193 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S.

915 (1972)................................... 16n

Henry v. Clarksdale Mun. Separate School Dist.,

409 F.2d 682 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 396

U.S. 940 (1969) ............................. 29n

Hereford v. Huntsville Bd. of Educ., 504 F.2d 857

(5th Cir. 1974) , cert, denied, 421 U.S. 913

(1975)....................................... 33n

Jackson v. Marvell School Dist. No. 22, 425 F.2d

211 (8th Cir. 1970) ........................ 30

Johnson v. Jackson Parish School Bd., 423 F.2d

1055 (5th Cir. 1970)........................ 30

Lee V. Demopolis City School Sys., 557 F.2d 1053

(5th Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 1014

(1978) ....................................... 33n-34n

Lee V. Linden City School Sys., 617 F.2d 383 (5th

Cir. 1980)................................... 33n

Lee V. Marengo County Bd. of Educ., 465 F.2d 369

(5th Cir. 1972) ............................. 40

McNeal V. Tate County Bd. of Educ., 508 F.2d 1017

(5th Cir. 1975) ............................. 48n

Milliken v. Bardley, 433 U.S. 267 ( 1 9 7 7 ) .......... 19n

Monroe v. Board of Comm'rs of Jackson, 391 U.S.

450 (1968)................................... 35n

Monroe v. Board of Comm'rs of Jackson, 427 F.2d

1005 (6th Cir. 197 0 ) ............ ............ 32, 42

Morgan v. Kerrigan, 530 F.2d 401 (1st Cir.), cert.

denied, 426 U.S. 935 (1976) ................ 40n

Pate V. Dade County School Bd., 588 F.2d 501 (5th

Cir.), cert, denied, 444 U.S. 835 (1979) . . . 33n

Pate V. Dade County School Bd., 434 F.2d 1151

(5th Cir. 1970), cert, denied, 402 U.S.

953 (197 1 ) ................................... 49

Plaquemines Parish School Bd. v. United States,

415 F.2d 817 (5th Cir. 1969)................ 48n

Quarles v. Oxford Mun. Separate School Dist., 487

F.2d 824 (5th Cir. 197 3 ) .................... 29n

v i i -

Page

Cases (continued):

Raney v. Board of Educ. of Gould, 391 U.S. 443

(1968) .................................

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Bd. of Educ.,

402 U.S. 1 (1971) ..................

Tasby V. Estes, 572 F.2d 1010 (5th Cir. 1978),

cert, dismissed as improvidently granted,

444 U.S. 437 (1980) .......................

United States v. Columbus Mun. Separate School

Dist. , 558 F.2d 228 (5th Cir. 1977), cert,

denied, 434 U.S. 1013 (1978) ..............

United States v. Gadsden County School Dist.,

572 F.2d 1049 (5th Cir. 1978) ............

United States v. Greenwood Mun. Separate School

Dist., 460 F.2d 1205 (5th Cir. 1972) . . . .

United States v. Greenwood Mun. Separate School

Dist., 406 F.2d 1086 (5th Cir.), cert, de

nied, 395 U.S. 907 (1969) ................

United States v. Hinds County School Bd., 433

F.2d 611 (5th Cir. 1970) ..................

United States v. Hinds County School Bd., No.

28030 (5th Cir. March 30, 1970)(unreported)

United States v. Hinds County School Bd., 417

F.2d 852 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied,

396 U.S. 1032 (197 0 ) ......................

United States v. Indianola Mun. Separate School

Dist., 410 F.2d 626 (5th Cir. 1969), cert.

denied, 396 U.S. 1011 (1970) ..............

United States v. Jefferson County Bd. of Educ.,

372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966), aff'd on

rehearing en banc, 380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir.),

cert, denied sub nom. Caddo Parish School

Bd. V. United States, 389 U.S. 940 (1967)

United States v. Mississippi [Laurel Mun. Sep

arate School Dist.], 567 F.2d 1276 (5th

Cir. 1978).................................

United States v. Scotland Neck City Bd. of Educ.,

407 U.S. 484 (1972) ......................

United States v. Seminole County School Dist.,

553 F.2d 992 (5th Cir. 1977) ..............

United States v. Texas Educ. Agency, 647 F.2d 504

(5th Cir.), cert, denied, 454 U.S. 1143

(1981).....................................

35n

3n, In,

25, 32

15n

15n-16n,

17n, 30

48n

29n

29n

3n

3n

31, 35n

29n

31&n, 48n

22n

25, 40&n,

42

16n, 33n

8n

- v i i i -

Page

Cases (continued):

United States v. Texas Educ. Agency, 532 F.2d 380

(5th Cir.), vacated and remanded, 429 U.S.

990 (1976), reaff'd, 364 F.2d 162 (5th Cir.

1977) , on rehearing, 579 F.2d 910 (5th Cir.

1978) , cert, denied, 443 U.S. 915 (1979) . .

of Brevard

1972) , cert,Weaver v. Board of Pub. Instruction

County, 467 F.2d 473 (5th Cir.

denied, 410 U.S. 982 ^ 9 7 3 ) .......... .

Wright v. Board of Pub. Instruction of Alachua

County, 445 F.2d 1397 (5th Cir. 1971)

Youngblood v. Board of Pub. Instruction of Bay

County, 448 F.2d 770 (5th Cir. 1971) . .

16n

33n, 44n

8n

8n

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. § 1 2 9 1 ................................. 1

28 U.S.C. § 1292(a) (1) .......................... 1

Miss. Code Ann. § 37-13-91 (Supp. 1985).......... lln

Miss. Code Ann. § 37-21-7(1)(f), (j) (Supp. 1985) . lln

Other Authorities:

Hawley & Rossell, Policy Alternatives for Minimi

zing White Flight, 4 Educ. Evaluation & Pol'y

Analysis 205 (1982) .................... .. <

Rossell, Applied Social Science Research: What

Does It Say About the Effectiveness Of School

Desegregation Plans?, 12 J. Legal Stud. 69

(1983) ..................................... ■

School Desegregation, Hearings Before the Subcomm.

on Civil & Constitutional Rights of the House

Comm, on the Judiciary, 97th Cong., 1st Sess.

(1981)......................................

Vobedja, "Magnet Schools Aid Desegregation But

Questions Remain," Washington Post, December

23, 1985, pp. Al, A8 ......................

46n

46n

46n

31n

- IX -

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

No. 85-4804

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

and

ZANDRA PITTMAN, Etc., ET AL.,

versus

THE STATE OF MISSISSIPPI, ET AL.,

and

HATTIESBURG MUNICIPAL SEPARATE

SCHOOL DISTRICT,

Plaintiff-Appel lee.

Plaintiffs-Interveners-Appellants

Defendants-Appel lees.

Defendant-Intervenor-Appel lee.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the

Southern District of Mississippi

RRTKP FOR APPRT.T.ANTS

Statement of Jurisdiction

This Court has jurisdiction of this appeal pursuant to 28

U.S.C. § 1291 because the Memorandum Opinion and Order appealed

from is a final order for purposes of appeal. The Court also

has jurisdiction of this appeal pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 1292(a)(1)

because the order appealed from denies to plaintiff-intervenors-

appellants the permanent injunctive relief which they sought below

(see R. 46 2) .

statement of Issue Presented for Review

The Hattiesburg elementary schools have never been effectively

desegregated; in the 1984-85 school year, five of eleven schools

were virtually all-Black and three other schools were each more

than 70% white. (59% of all elementary students were Black.)

The district court rejected a school pairing and clustering plan

which would have reassigned Black and white students in 1986-87

in substantial numbers to every school. It approved a primarily

voluntary plan to convert two of the all-Black schools to "magnet

schools" in 1987-88 and leave two other all-Black schools unaffec

ted. The issue presented for review is whether the district

court's decision meets applicable constitutional standards for

eliminating all vestiges of dual school systems where:

(a) the court made no findings that distances or pupil

transportation times between paired or clustered

schools were excessive, or that the pairing and

clustering plan was otherwise infeasible or imprac

tical ;

(b) the court postponed any assessment of the magnet

plan's effectiveness or modification of its order

until the end of the 1989-90 school year; and

(c) the sole ground advanced by the court for its ruling

was that implementation of the pairing and clustering

plan would cause greater future "white flight" from

the school district than would the magnet plan.

Statement of the Case

1. Proceedings Below.

This action was originally filed in 1970 by the United States

against the State of Mississippi and several state agencies and

officials, seeking the desegregation of 13 public school systems

(R.Exc. 3 [Dkt. Ent. p. 1]). The Hattiesburg Municipal Separate

- 2 -

School District (HMSSD) intervened as a defendant (iJLi). On July

15, 1970 the district court approved a pupil assignment plan embod

ied in a consent decree between the United States and the HMSSD

(D-X 53). Following the Supreme Court's decision in gwanjl^> the

district court on July 21, 1971 approved the school system's plan

for further student desegregation (D-X 51). Thereafter, HMSSD con

tinued to send semi-annual reports^ to the court and to the gov

ernment, but there were no significant proceedings in the matter

for a dozen years.-'

On April 23, 1983, counsel for the present appellants — Black

children attending the HMSSD schools and their parents — wrote

to counsel for the HMSSD and for the United States, urging that

meaningful steps be taken to eliminate continuing elementary school

segregation (R. 7-8; PI-X 13). The Black children and their par

ents on February 21, 1984 formally moved to intervene in this

lawsuit as plaintiffs (R. 1). They alleged that the HMSSD elemen

tary schools^ had never been adequately desegregated and that

the United States had failed to protect the interests of Black

^Swann v. Char 1 otte-Mecklenbura Bd. of Educ. , 402 U.S. 1

(1971) .

^The reports, required by a 1970 supplemental district court

order (D-X 52), followed the format announced by this Court in

United States v. Hinds Countv School Bd., No. 28030 (5th Cir.

March 30, 1970)(unreported), reprinted in f 433 F.2d 611, 612

n.l, 618-19 (5th Cir. 1970). They are collected in PI-X 1 intro

duced below.

^On one occasion the parties agreed to, and the district

court approved, a minor alteration of the desegregation plan

(R.Exc. 24 [Dkt. Ent. p. 12]) but most of the elementary schools

continued to be racially identifiable (see R.Exc. 80, 84 [G-X 1;

PI-X 9]; Tr. 18, 142) .

^Neither the proceedings below nor this appeal involve any

contested issues relating to the HMSSD secondary schools.

- 3 -

pupils in the HMSSD by seeking further relief to accomplish this

goal (R. 2-4). The HMSSD opposed intervention (R. 58-60) and

the government asked the district court to withhold ruling (R. 62-

68), both parties indicating that they were actively engaged in

negotiations to resolve any remaining problems (R. 56, 65-66).^

The district court delayed consideration of the intervention to

permit these negotiations to go forward.

On July 17, 1984 the HMSSD and the United States submitted

to the district court a consent decree which proposed further

pupil desegregation in the elementary grades through the altera

tion of zone lines, a school closing, and creation of two "magnet"

schools (R. 99; PI-X 33).® Following a July 26, 1984 hearing on

the motion to intervene (R. Vol. 3), the district court on August

2, 1984 ruled that the applicant Black children and parents should

be allowed to enter the suit (R. 134).’̂ The intervening plain

tiffs and the HMSSD then worked out a procedure for the orderly

submission to and consideration by the district court of plans

to desegregate Hattiesburg's elementary schools.® The United

®The discussions between HMSSD and the government began only

after receipt of the April 23, 1983 letter from counsel for the

Black children and their parents. Response of the United

States to Motion to Intervene, pp. 3-5 (R. 64-66).

®This proposed consent decree, like the one subsequently

filed on September 4, 1985 by HMSSD, Mississippi, and the United

States (R. 524, R.Exc. 85 [D-X 57]), also contained provisions

dealing with other subjects (such as student discipline and as

signment to special education classes). The district court ap

proved these provisions along with the magnet pupil assignment

plan and no issue arises with respect to them on this appeal.

^Appellants' Complaint in Intervention was filed August 24,

1984 (R. 148).

®This agreement was embodied in a consent order between plain-

- 4 -

States declined to agree to this procedure, arguing instead that

the court should first hold a hearing on the magnet plan contained

within the July 17, 1984 proposed consent decree (R. 164, 169).

The district court rejected that suggestion.

Thereafter, in accordance with the scheduling order, plans

prepared by desegregation consultants contacted by the school

district^ were filed with the court on December 10, 1984 (R. 257 );

two "magnet" proposals were submitted on behalf of HMSSD on Decem

ber 10, 1984 (R. 207);^° and a pairing plan drafted for plaintiff

Black children by Dr. Michael Stolee was tendered on January 21,

1985 (R. 362; R.Exc. 126 [PI-X 24]). Plaintiff Black children

filed objections to the HMSSD plans (R. 322); the district filed

objections to the plan drawn by Dr. Stolee (R. 393) ; and discovery

between these parties was completed (see R. 335-44, 380-92, 402-04,

408-20; PI-X 11, 21).

tiff Black children and the HMSSD which the district court en

tered on September 24, 1984 (R. 171; see R. 705, R.Exc. 65 [Mem.

Op. 3]). HMSSD agreed to contact the University of Miami Race

Desegregation Assistance Center (the center funded under Title

IV of the 1964 Civil Rights Act which serves Mississippi), as

well as Dr. Larry Winecoff, of the University of South Carolina,

and to request that each design two plans for desegregating the

system's elementary schools: one based on "magnet schools" and

one utilizing other techniques. The resulting plans were to be

circulated to all parties, who could file them with the court

and who would also have an opportunity to submit any other pro

posals for the court's consideration. The order set deadlines

for the submission of plans and objections and for the completion

of discovery; and it called for an evidentiary hearing before

the district court "on or about February 15, 1985" (R. 177).

^See supra note 8. Dr. Winecoffs plan was co-authored by

Dr. Burnett Joiner, of Grambling University.

^^These submissions were referred to during the course of the

proceedings below as the "District" and "District Alternative"

plans.

- 5 -

On April 22, 1985 plaintiff Black children, by written motion,

sought the prompt scheduling of a hearing (R. 455). Judge Russell

subsequently withdrew from the case and it was reassigned to the

Hon. Tom S. Lee. A pre-trial conference was held September 10,

1985 (R. 563)^^ and an evidentiary hearing conducted in Hatties

burg on October 1-4, 1985 (R. 67 3). On October 21 , 1985 the dis

trict court issued its Memorandum Opinion and Order approving

for implementation the magnet (voluntary) desegregation plan sup

ported by the United States and HMSSD (R. 703, R.Exc. 63). The

Notice of Appeal from this Order was filed November 4, 1985 (R.

720).^2

2. Statement of Facts

This appeal concerns the adequacy of a plan approved by the

district court to eliminate segregated elementary schools in the

HMSSD. Neither the 1970 consent decree nor the 1971 order of the

^^In the meantime, the United States negotiated with the

HMSSD in an effort to develop yet another magnet desegregation

proposal for the District's elementary schools. Such a proposal

was ultimately filed, in the form of a suggested consent decree,

by the United States, the State of Mississippi, and HMSSD, on

September 4, 1985 (R. 520, R.Exc. 85 [D-X 57]). As we indicate

infra pp. 7a-8a, the basic student assignment features of the

"magnet" plan supported by HMSSD and the United States have re

mained unchanged in all of the various plans which either or both

of those parties have submitted.

^^The Order was subsequently modified with the consent of

all parties so as to include counsel for plaintiff Black children

among those who are to receive copies of future semi-annual re

ports to the court (R. 723-24). In addition, correspondence be

tween the parties has continued with respect to the matters on

which HMSSD was required by the district court's Order to take

action (free transportation for enrollees in the magnet schools

and controls on admission to prevent magnet school selections

which would adversely affect the desegregation status of other

facilities, see R. 718-19, R.Exc. 78-79 [Mem. Op. 16-17]).

- 6 -

district court succosded in achisving that constitutional objec~

tive.^3 In March, 1985, five of the district's eleven elementary

schools were 89% —100% Black (R. 704, R.Exc. 64 [Mem. Op. 2n.3]).^^

Together, these five schools enrolled more than 73% of all Black

Hattiesburg elementary students (PI-X 37; see also R. 705, R.Exc.

65 [Mem. Op. 3 n.4]).^^ Conversely, 77% of all white children

were enrolled in three historically white schools that each re

mained more than 70% white (R.Exc. 84 [PI-X 9]; PI-X 37; Tr. 131-

3 2 ) These patterns had remained unchanged for a dozen years

(see R.Exc. 80, 8 4 [G-X 1; PI-X 9 ]) .

^^The 1970 decree replaced HMSSD's use of a freedom-of-choice

plan adopted in 1964, which had had little result. For example,

no white student ever chose to attend a formerly Black school

under free choice (Tr. 35, 133).

After entry of the 1971 court order, the secondary schools

of the HMSSD were fully desegregated through pairing and grade

consolidation, s ^ D-X 38, pp. 5-6 [Race Desegregation Assistance

Center report and plans]. However, both the 1970 decree and the

1971 court-ordered plan utilized a system of contiguous geographic

zoning for elementary school assignments which did not alter the

historic racial identifiability of the schools (see R.Exc. 80,

84 [G-X 1; PI-X 9]; Tr. 18, 142).

Although majority-to-minority transfers are authorized under

the 1970 and 1971 orders, none has ever been used by a white ele

mentary school pupil (s^ PI-X 1; D-X 8). The number of major-

ity-to-minority transfers by Black elementary school pupils has

totalled about 50-60 annually in recent years (s^ D-X 8). Major-

ity-to-minority transfers are limited by the capacity of the re

ceiving schools (Tr. 25, 123-24) and the HMSSD has not provided

transportation for pupils making these transfers (Tr. 314-15) .

Compare Swann. 402 U.S. at 26-27 ; Carr v. Montgomery County Bd. of

Educ.. 429 F.2d 382, 386 (5th Cir. 1970) and cases cited.

'̂̂ Of these, all but one school (Walthall)

for Black students under the dual system (see

Tr. 48-50 , 132-33).

15r

had been designated

R.Exc. 84 [PI-X 9] ;

^The four historically Black elementary schools, s ^ supra

note 14, housed 63% of all Black pupils (PI-X 36, 37).

16See Table 1, inf ra p. 2a.

"̂̂ The school district argued that its adherence to the zoning

- 7 -

a. The Hattiesburg district

HMSSD is a small system, in September 1985 enrolling 2,972

elementary pupils in grades 1-6 (exclusive of special education

students) (D-X 10-A). The district covers a compact geographical

area, within which the reassignment of pupils to bring about de

segregation is entirely practicable (Tr. 662-63 [Dr. Stolee], 650

[Dr. Foster]).18

scheme embodied in the 1971 court order made HMSSD a unitary sys

tem — in spite of the substantial school segregation which re

mained at the elementary level. (See Attachment C to Pre-Trial

Order, p. 2, R. 580.) Comoare, e.g., Flax v. Potts, 464 F.2d

865, 868 (5th Cir.), cert, denied. 409 U.S. 1007 (1972). Thus,

it contended, no new plan could be mandated; rather, the court

was required to approve its voluntary proposal of a magnet plan

which might enhance desegregation. However, no order had ever

been entered adjudicating HMSSD to be unitary. See, e.g., United

States V. Texas Educ. Agency, 647 F.2d 504, 508-09 (5th Cir.),

cert, denied. 454 U.S. 1143 (1981); Youngblood v. Board of Pub.

Instruction of Bav County, 448 F.2d 770 (5th Cir. 1971); Wrjght

V. Board of Pub. Instruction of Alachua County, 445 F.2d 1397

(5th Cir. 1971) .

Following the pre-trial conference and the submission of

briefs (see R. 533; Tr. 4), the district court ruled that HMSSD

was not unitary (Tr. 4-5; see R. 7 04, R.Exc. 64 [Mem. Op. 2 n.l])

and proceeded to evaluate the adequacy of the plans submitted by

the parties "to achieve the reaui red result of further desegre

gation" (R. 717; R.Exc. 77 [Mem. Op. 15])(emphasis supplied).

HMSSD has not cross-appealed from these rulings.

^^There was no testimony that it is physically or geograph

ically impractical to desegregate any HMSSD elementary school.

Compare, e.g. . Tr. 88 (Dr. Spinks, HMSSD Superintendent f rom 1966-

1985: "I just don't think they'll [whites will] go to that school

[Eureka ] ") .

The district is small enough that an assignment change which

caused an early bus run to end up at Thames, on the western side

of town, rather than at Love, to the east, could be compensated

for merely by shifting driver assignments for the second bus runs,

without purchasing any additional equipment (Tr. 324-29); HMSSD

Transportation Supervisor Goodbread also testified that it might

be possible to cut costs and new equipment needs under a pairing

and clustering plan by routing the buses to make triple runs (Tr.

349-50, 353, 357). [footnote continued on next page]

- 8 -

HMSSD currently operates some 32 school buses on double runs

making neighborhood pick-ups — 22 on elementary school routes

(of which 7 are for special education students) (Tr. 279, 345,

350). Under the plan approved below, HMSSD will also, for the

first time, provide free transportation to any student exercising

a majority-to-minority transfer, as well as to any student admitted

to a magnet elementary s c h o o l , s o long as the student resides

O Aat least a mile from the school which he or she is to attend.

The street travel distances between elementary school facilities

which would be paired or clustered, under the plan drawn up by

Dr. Stolee for the plaintiff Black children, range from 2.3 miles

to 6.4 miles — and the school-to-school travel times from 10

minutes to 18 minutes by school bus (D-X 41; PI-X 34; Tr. 315-

1 7 ) . (See map infra p. la, showing travel times and distances

A map drawn to scale, indicating the locations of the elemen

tary schools in the HMSSD and the street driving distances between

them by school bus, appears inf ra p. la.

^^As originally presented, the magnet plan proposed by HMSSD

and the United States did not make provision for the transporta

tion of pupils to the magnet schools without payment of a fee.

However, the district court's October 21, 1985 Order directed

HMSSD to "present a report to the court regarding the feasibility

of and need for providing free transportation for children elect

ing to attend magnet schools" (R. 719, R.Exc. 79 [Mem. Op. 17]).

The district has advised other counsel and the court that it will

furnish such transportation.

^®No accurate prediction of the increase in pupil transpor

tation capacity which will be required under the district's plan

could be devised (s^ Tr. 349-50). The estimates prepared by

HMSSD's Transportation Director were based upon the unreliable,

inaccurate attendance projections submitted with the plan (Tr.

323). See inf ra pp. 19-22.

^^Past majority-to-minority transfers, for which HMSSD will

now be providing transportation, have included transfers between

nearly all of the schools which would be paired or clustered under

the Stolee plan. (See map inf ra p. la and PI-X 1; D-X 8.)

- 9 -

between schools and their March, 1985 racial composition in grades

1-6 .)

b. The magnet plan

The magnet plan approved by the district court would convert

two of the five virtually all-Black elementary schools^^ (Jones

and Walthall) into magnet facilities with specialized curricular

emphases.23 Equal numbers of Black and white students would be

admitted to these schools upon approval of their voluntary appli

cations, so as to maintain a 50% Black, 50% white enrollment in

each facility.24 a third Black school (Grace Love) would be con-

22See Table 1, inf ra p. 2a.

22slack pupils who formerly attended these facilities and

who would not be enrolled in the magnet programs would be reas

signed: at least 60 Blacks from Jones to Grace Christian (a for

merly white school), 118 Blacks from Walthall to Eureka (still a

virtually al1-Black school)(R.Exc. 124 [D-X 33]; Tr. 146-47, 194-

95) , and 46 Blacks who now attend Jones under a special program

to other "neighborhood" schools (Tr. 236-37). These numbers will

increase to the extent that fewer pupils who formerly attended

Jones and Walthall volunteer for the magnet schools than the num

ber of places reserved for them under the plan (see Tr. 232-35)

or to the extent that fewer white than Black students request

admission to the magnet schools (Tr. 194-95).

2 4r 1985 enrollment of the HMSSD in grades 1-6 was

Table 1, inf ra p. 2a), and the government's ex-

, Christine Rossell, testified that even in thethe district's

‘The March,

59.4% Black (see

pert witness. Dr,absence of any further desegregation measures,

proportion of Black students in the elementary grades could be

expected to increase each year (Tr. 6 07). See also Tr. 505 (aver

age annual decrease of white students over ten-year period is

2%); Argument on Hearing on Motion to Intervene, July 26, 1984,

R. Vol. 3, p. 48.

The 50% limitation on Black enrollment is intended "to make

those magnet schools more attractive to the white community" (Tr.

259). "Rather than whites being in the minority, there will be

an equal number of blacks and whites in the magnet schools" (Tr.

257 ) .

- 10 -

2 5solidated with a small, racially mixed facility (Eaton) that

would be closed, resulting in a projected enrollment in grades

one through six^® that would be 73% Black.27 The two remaining

57)

2^Eaton was a white school under the dual system (Tr. 48,

It is located on the eastern edge of the district in an

area whose population has been declining for years. The school's

enrollment, well mixed racially, has also been declining for an

extended period of time (Tr. 57; see R.Exc. 80 [G-X 1]). Eaton

is located five blocks from the historically Black school, Grace

Love, into which it would be closed under the plan approved below

(Tr. 60) and all but five houses in the Eaton zone are within a

mile (walking distance) of Love (Tr. 286).

1-6 ,

dual

2^Throughout this brief we

the only elementary grades

system (see Tr. 114) .

focus upon

offered in

enrolIment

the HMSSD

in grades

under the

The magnet plans submitted by HMSSD originally contemplated

that kindergarten and pre-kindergarten programs — which are vol

untary and not subject to Mississippi's compulsory attendance law,

see Miss. Code Ann. § 37-13-91 (Supp. 1985) — would be offered

only at the magnet schools [July 17, 1984 and December 10, 1984

"District" plan] or only at the non-magnet, formerly Black schools,

Bethune, Eureka, and Love [December 10, 1984 "District Alterna

tive" plan and September 4, 1985 proposed consent decree plan].

For this reason, the enrollment projections accompanying each

of these plans included an estimated number of white kindergarten

or pre-K pupils (see R. 231, 247 , 558; R.Exc. 119).

However, the Mississippi Educational Reform Act of 1982,

Miss. Code Ann. § 37- 21-7 (1) (f) , (j) (Supp. 1985) , as implemented

by the State Board of Education, requires that all public school

systems Offer (voluntary) kindergarten programs at schools

(Tr. 113-14). HMSSD officials admitted at trial that whites were

unlikely to select kindergarten programs at formerly Black schools

for their children in preference to kindergarten offerings in

their "neighborhood" schools (Tr. 115, 175; see also Tr. 57 0 [gov

ernment's expert witness Dr. Rossell]).

Moreover, both kindergarten and pre-kindergarten programs

for "developmentally delayed" 4-year-olds are generally self-con

tained; pupils in these programs, including any white children

whose parents choose to enroll them, will have little or no con

tact with Black students in the regular curriculum at the schools,

except possibly in the lunchroom or on the playground or school

bus (Tr. 263). The school district's expert witness, Dr. Wine-

coff, admitted that combining white kindergarten pupils with Black

students in grades 1—6 to produce a "desegregated" school is the

[footnote 26 continued & footnote 27 on next page]

- 11 -

virtually all-Black schools, Bethune and Eureka, will neither be

come "magnets" nor have any white students in grades 1-6 reas

signed to them. Finally, several attendance zone changes would

be made that would reassign Black children to formerly white

schools.^®

The enrollment projections submitted with the magnet plan

indicate that Eureka and Bethune will be 97% and 99% Black, respec

tively,^^ in grades 1-6^® (R.Exc. 124 [D-X 33]), enrolling ap-

same as characterizing a school in which all pupils in grades 1-3

were Black and all pupils in grades 4-6 were white as "desegre

gated" (Tr. 519).

^^This figure is determined by adding together the Eaton and

Love enrollments shown on D-X 33 (R.Exc. 124)(the same projections

appear on D-X 33 and as Attachment Two to the September 4, 1985

proposed consent decree plan which the district court approved,

R. 558, R.Exc. 119; Tr. 83, 157-58), exclusive of pre-K and

kindergarten students, and subtracting the Black students who will

be shifted to Thames (see infra note 28).

^^These shifts primarily involve the reassignment of speci

fied apartment complexes in the HMSSD which have previously been

treated as units for student placement purposes (s£s Tr. 295-300).

For example, the Bonhomie Apartments are located in the southwes

tern area of the district, west of U.S. 49. See map inf ra p. la.

The "natural" school of assignment for this area, according to

both School Superintendent Walker and the government's expert

witness Dr. Rossell, is Thames Elementary (Tr. 584, 822), but it

has been zoned to Bethune since the time of the dual system (Tr.

136-38). Black students living in the Bonhomie Apartments have

been transported past Bethune to Love, while other Black students

in the same area have attended Bethune (Tr. 212, 216-18, 831-32).

Under the magnet plan, the 61 Black students living in the Bon

homie Apartments, as well as 50 Black students residing nearby,

will be reassigned to Thames (R. 713, R.Exc. 73 [Mem. Op. 11 n.23];

R.Exc. 124 [D-X 33]; D-X 7 ; Tr. 216-18). 62 Black students living

in the Pineview Apartments, who are presently transported by school

bus to Bethune (Tr. 296), will be shifted to Woodley under the

plan (D-X 7; R.Exc. 124 [D-X 33]). 11 Black students residing

in the Christina Apartments will be shifted from the Woodley zone

to the Grace Christian zone (R.Exc. 124 [D-X 33]).

^^Dr. Spinks (Tr. 85, 120-21), Dr. Joiner (Tr. 464-65), Dr.

Winecoff (Tr. 504), Dr. Rossell (R. 613-14, R.Exc. 157-58 [G-X 2,

pp. 16-17]; Tr. 569-71, 610-11), and Dr. Stolee (Tr. 688-91) all

[footnote 29 continued & footnote 30 on next page]

- 12 -

31proximately 34% of all HMSSD Black children in grades 1-6.

There are no firm commitments to take further action in order to

desegregate these two s c h o o l s . the Black population of Love

recognized that Bethune and Eureka would remain racially iden

tifiable under the plan.

30gee supra note 26. These figures were determined by adding

together the enrollments shown on D—X 33/ exclusive of pre—K and

kindergarten students/ and subtracting the number of Black students

who are expected to attend the magnet schools or to exercise ma—

jority-to-minority transfers/ or who will be shifted to other

schools by zone line changes. The various projections presented

at the hearing are discussed infra pp. 19-22.

31g0e pi-x 39. The figure derived when using Dr. Rossell's

corrections to the projections submitted with the plans/ s ^ infra

p. 21, is 36.6% of all Black elementary pupils attending schools

more than 95% Black (§^ PI-X 41). Including kindergarten stu

dents as originally projected by the district, it is 40% (Tr. 127

29) .

^^The written plan contained in the proposed consent decree

filed by HMSSD, the United States, and Mississippi, which was

approved below, provides that "[t]he School District shall give

consideration to converting Eureka to a magnet school afte.r— t.he

1987-88 school year based upon the School District's evaluation

of the Jones and Walthall magnet programs and the community need

for or interest in additional or alternative magnet programs"

(R. 542, R.Exc. 103 [p. 19])(emphasis supplied). At the hearing,

however, former Superintendent Spinks (who served in that capacity

from the inception of this case until his retirement at the close

of the 1984-85 school year, Tr. 15) asserted that whites could

never be attracted to the facility and doubted that its conversion

to a magnet school is feasible (Tr. 85-88, 148), and current Su

perintendent Walker called it "very improbable" (Tr. 245).

As to Bethune, Dr. Winecoff and Dr. Joiner originally devel

oped projections indicating that 104 white children would attend

the school in kindergarten and pre-kindergarten programs (Tr. 469-

74). The same projections were submitted with the District Al

ternative and September 4, 1985 magnet plans supported by the

HMSSD (Tr. 157-58) , even though kindergarten will now be available

at all schools in accordance with state law (see supra note 26).

At the hearing. Superintendent Walker said that the projections

were not reduced because the school district felt that the Extended

Day program now to be offered exclusively at Bethune would lead

at least this number of white parents to enroll their children

through majority—to-minority transfers in grades 1-6 at Bethune

(Tr. 176, 179) — although the projection chart (R.Exc. 124 [D-X

33]) was never modified to indicate the schools from which these

- 13 -

(when consolidated with Eaton) is added, 42% of Black students

in grades 1-6 will attend these three facilities even if the mag

net schools meet their enrollment targets.

The magnet schools at Jones and Walthall will not become oper

ational until the 1987-88 school year (Tr. 199).^'^ The plan is

then to function for three years before its success in desegre

gating the HMSSD elementary schools will be evaluated (R. 542,

R.Exc. 103 [p. 1 9 ] ) . In fact, the sponsors of the magnet plan

students would be coming (Tr. 271-72)

t

gi

The government's expert initially concluded that "the assump

tion that 104 white students would enroll in Bethune, in addition

o kindergarten and pre-kindergarten, seemed unrealistic to me

iven that the school would still remain predominantly black

. . ." (R. 613, R.Exc. 157 [G-X 2, p. 16]; Tr. 57 0). She later

said her judgment "may have in fact been too conservative" because

it was not based on the understanding that Bethune would offer

the only school-site Extended Day program in the HMSSD; under

these circumstances, she thought it was "possible" that Bethune

would be less than 80% Black (Tr. 566). There was no direct evi

dence of how many white families are willing to send their chil

dren to Bethune for the Extended Day, or any other program.

33See inf ra note 37.

1986-87 the only pupil assignment changes that will

occur are (a) the closing of Eaton and shifting of its pupils to

Love (R. 528, R.Exc. 89 [p. 5]; s^e supra note 25) j (b) the modest

zone line adjustments affecting Black students (id.; S.ypJLg

note 28); (c) the availability of free transportation for major-

ity-to-minority transfers (R. 533, R.Exc. 94 [p. 10];

note 13); and (d) the option for Black students living in the

Jones and Walthall attendance areas to elect to attend either

Eureka or Grace Christian, respectively (the facilities to which

former Jones and Walthall students not attending the magnet pro

grams will be reassigned in 1987-88) (R. 539, R.Exc. 100 [p. 16];

see supra note 23). In addition, "Basic Skills Learning Centers"

are to be established in 1986-87 at the Bethune, Eureka and Love

schools, to include 4-year-old "developmentally-delayed" pre-kin

dergarten programs, breakfast programs, and an Extended Day program

at Bethune only (R. 534-35, R.Exc. 95-96 [pp. 11-12]; supra

note 32; inf ra note 48).

^^The district court did reject the suggestion that the HMSSD

must be declared "unitary" so long as the magnet plan had been

effectuated for three years without interference by school author

ities, irrespective of its results (see R. 548, R.Exc. 109 [p.

25]). R. 716, R.Exc. 76 [Mem. Op. 14]

- 14 -

expect that the magnet schools will not reach their projected

enrollments of 240 pupils each (R.Exc. 124 [D-X 33]) for several

y e a r s . D u r i n g that time, the other HMSSD elementary schools

may be less integrated than shown on the projections submitted

with the plan (R.Exc. 124 [D-X 33]).^^

c. The Stolee Plan

The Stolee plan, supported by plaintiff Black children, would

be implemented at once to desegregate all of the district's ele

mentary school facilities through the techniques of pairing and

clustering with appropriate grade restructuring^^ and the reten-

^^Tr. 193, 200, 268 [Dr. Walker], 557-58 [Dr. Rossell]; aeg

al?o Tr. 267-68 [Dr. Walker: although each magnet school is de

signed to house 240 students, if 120 Black pupils and 30 white

pupils apply, only 30 Black students will be admitted, along with

all white applicants], 602 [Dr. Rossell: magnet schools in minor

ity neighborhoods are underenrolled].

^^The attendance projections submitted with the plan are

based upon the ultimate, fully successful operation of the magnet

schools with anticipated total enrollments of 240 students each

— enrollments which, as noted in text, the schools may well not

reach until at least the third year of operation. Thus, during

the 1987-88 and 1988-89 school years, if Jones and Walthall are

each maintained with small student bodies that are 50% Black (per

haps only 60 students each, see Tr. 267-68), then fewer students

than are shown on the attendance projections will transfer from

their home schools to the magnet programs — and if this occurs,

it will obviously affect the racial compositions of the non-magnet

schools during those years.

For example, if fewer than 155 students leave Thames for the

magnet schools, fewer Black students will be able to exercise

maj ority-to-minority transfers to Thames (Tr. 480-82). Thames

will then remain more heavily white and Bethune, shown on the projections as the source of majority—to—minority transfers to

Thames, will remain more heavily Black.

^®These techniques have long been employed within this Cir

cuit. S^, e. g. . Davis v. East Baton Rouae Parish School Bd^ ,

721 F.2d 1425 (5th Cir. 1983), aff'g

1981); Tasbv v. Estes. 572 F.2d 1010,

dismissed as imorovidentlv granted,

- 15 -

514 F. Supp. 869 (E.D. La.

1014 (5th Cir. 1978) ,cert.

444 U.S. 437 (1980); United

39 j-tion of zones for currently desegregated schools. It reassigns

both Black and white students^® but retains neighborhood, peer.

-States V. Columbus Mun. Separate School Dist. , 558 F.2d 228 (5th

Cir. 1977 ), cert, denied. 434 U.S. 1013 (1978); lJpitgd_St^t£_s

V. Seminole Countv School Dist., 553 F.2d 992, 995 & n.8 (5th

Cir. 1977); United States v. Texas Educ. Agency, 532 F.2d 380,

394 (5th Cir.), vacated and remanded on other grounds, 429 U.S. 990

(1976), reaff'd. 564 F.2d 162 (5th Cir. 1977), on rehearing. 579

F.2d 910 (5th Cir. 1978), cert, denied, 443 U.S. 915 (1979); Cj^-

neros v. Corpus Christi Indeo. School D.i.st̂ > 467 F.2d 142, 152-53

(5th Cir. 197 2) (en banc) . cert, denied, 413 U.S. 920 (197 3); FJL.ax

V. Potts. 464 F.2d 865, 868 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S.

1007 (1972)(quoting Allen v. Board of Pub. Instruction of Broward

County. 432 F.2d 362, 367 (5th Cir. 1970), cert, denied. 402 U.S.

952 (1971)); Acree v. Countv Bd. of Educ., 458 F.2d 486, 487 (5th

Cir.), cert, denied. 409 U.S. 1006 (1972).

^^Dr. Stolee explained how the plan was designed to minimize

reassignments and busing (Tr. 666-69).

^^There was disagreement about the extent to which the magnet

plan and the Stolee plan would distribute the burdens of desegre

gation equitably. e.q. , Harrington v. Colquitt County Bd. of

Educ.. 460 F.2d 193, 196 n.3 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 409 U.S.

915 (1972) .

Dr. Stolee calculated the total number of students subject

to mandatory reassignments. Under his plan, 604 Black and 582

white pupils will be reassigned to different schools for three,

or possibly four, of the six elementary grades (Tr. 684; Tr.

211-12, 669-72, 780). Superintendent Walker agreed that these

figures were relatively equitable (Tr. 824).

In contrast, under the magnet plan's attendance changes (see

supra notes 23, 28), far more Black than white students would

be reassigned, and for all of the elementary grades. "[T]he 497

black children involuntarily transferred compared to the 65 white

children is . . . inequitable" (Tr. 686 [Dr. Stolee]).

Dr. Walker did not view many of these mandatory reassignments

as burdensome because "[tjhere are certain students in the School

District plan which would be reassigned to a school which should

be or which ought to be their neighborhood school" (Tr. 820);

these reassignments, he said, are a "[d]isruption . . . [but] not

a burden" (Tr. 834; accord. Tr. 581 [Dr. Rossell]; but see Tr. 586

[individual students and parents might take a different view]).

Excluding such changes. Dr. Walker calculated the magnet plan's

"burdensome reassignments" as affecting 178 Black and 0 white

students (Tr. 820-24).

The magnet plan was still more equitable than pairing and

- 16 -

and class groupings throughout the elementary school y e a r s . A s

previously noted. Black students have in the past few years exer

cised majority-to-minority transfers between virtually all of the

schools paired or clustered under Dr. Stolee's plan'^^ and the

distances and transportation times between schools grouped under

the plan are hardly excessive. 43

clustering, according to Dr. Walker: if whites who would be reas

signed left the system but the pairing plan remained unaltered

(but see Tr. 588-89, 834-35), the proportion of the burden borne

by Blacks would increase. "At the end of the second year, the

School District plan would have less relative burden or less rela

tive inequity on blacks than the Stolee plan. Stolee would have

a burden on 604 blacks, and under his plan on only 378 whites

after we take into account white flight, thus leaving a difference

in relative burden between black and white of 226 students, where

as our difference in relative burden between black and white would

only be 178 students" (Tr. 825).

The district court's brief discussion of this matter confused

the numbers (R. 713, R.Exc. 73 [Mem. Op. 11 n.24]). 532 was the

total which Dr. Rossell computed while on the witness stand for

mandatory reassignments, according to her analysis of the magnet

plan (Tr. 581). In fact, her arithmetic was wrong. According to

her chart (R. 626 , R.Exc. 17 0 [G-X 2, p. 28]), the total mandatory

reassignments (including the closing of Eaton) are 462 Black, 66

white; the total mandatory and voluntary transfers projected by

her are 613 Black, 286 white.

In any event, the lower court's view of the relative equities

does not appear to have been an independent basis for its judgment

and this Court need not resolve the dispute in order to reverse.

^^See Tr. 727-29; United States v. Columbus Mun. Separate

School Dist.. 558 F.2d at 232 n.l6 ("Pairing also forces students

to change schools after third grade. Though that is an undesirable

effect, its importance is mitigated by the fact that students

retain their same classmates despite the change of schools . . . ") .

42See supra note 21.

^^See map infra p. 1; supra p. 9, text at note 21. While

the times and distances shown are for school-to-school routes,

the system has considerable experience in designing efficient

routing for transporting students from neighborhood pick-up points

across the city to schools, as it currently does for special edu

cation pupils (s^ PI-X 11 [bus routes]), pupils in the Reach

program (see Tr. 351), secondary students, and as it will be re-

- 17 -

Dr. Stolee's plan was "designed to be implemented first, with

magnet options following if the School Board so desires"^^ be

cause, in his view,

magnet schools can be a helpful desegregative

device. However, the mandatory desegregation

program must come first, children must be trans

ferred first, and after that, parents can be given

a choice of magnet schools. Such a pattern would

desegregate the schools now, provide parents with

a choice concerning their child's education, and

make the magnet schools more attractive.

d. Effectiveness of the plans and "white flight"

The two plans upon which principal attention was focused be-

icw'̂ ̂ are summarized and compared in Table 2, infra pp. 3a-5a.

As indicated in that table, there are substantial differences in

the mechanics, timing and expected outcomes of the two plans.

The most significant fact is that even when the magnet schools

have had a three-year opportunity to achieve their projected en

rollments, two historically Black schools will remain — in grades

1 - 6 __ 9 7 % and 99% Black, respectively, unless white students

suddenly, and contrary to the experience of the past decade. 47

quired to do next year for majority-to-minority transfer pupils

and starting in 1987-88 for magnet school attendees, under the

Order below suora note 19 and accompanying text) . HMSSD cur

rently uses a computer in laying out routes (Tr. 283, 325) and

at the hearing, its transportation supervisor demonstrated his

facility for solving problems by appropriate route changes (§^,

e.Q.. Tr. 324-29, 342-45, 346-48).

44

45

R. 370, R.Exc. 133 [PI-X 24, p. 8]).

Id. at 369 , R.Exc. 132 [PI-X 24, p. 7]. at 374-75,

R.Exc. 137-38 [PI-X 24, pp. 12-13].

^^See "Note on Desegregation Plans before District Court,"

inf ra pp. 7a-8a.

~̂̂ See supra note 13.

- 18 -

decide to transfer to these schools.^® Conversely, the Stolee

plan is designed to produce substantial desegregation at every

Hattiesburg school in its first year of implementation.

Under the magnet plan, only Jones and Walthall (starting in

1987-88) will have controlled student admissions (on a 50% white,

50% Black basis. The racial composition of the other elemen

tary schools in HMSSD will depend upon the pattern of majority-

to-minority transfers and the facilities from which magnet school

enrollees are drawn.Accordingly, when the plan was submitted,

it included post-implementation enrollment projections for all

schools (R.Exc. 119; R.Exc. 124 [D-X 33]), which are reflected

in Table 2, infra p. 3a-5a.

The testimony about these projections was conflicting. For

instance, the plan reserves spaces in the magnet schools for pu

pils who did not previously attend Jones and Walthall, to "provide

^^See supra note 32. As the court below noted (R. 712, R.Exc.

72 [Mem. Op. 10 n.22]), Bethune, Eureka and Love currently have

the lowest test scores in the school district (§^ Tr. 165; D-X

28). Common sense therefore suggests that white parents whose

children are presently in schools with higher-performing students

will be unlikely to transfer them voluntarily to Bethune, Eureka

or Love. Cf^ Tr. 588 [Dr. Rossell: "[W]e know from the research

that the blacks are willing to volunteer to go to white schools

because— for a whole variety of reasons. They perceive them as

better— and the whites are not"]. The "Basic_ Skills Learning

Centers" to be implemented in these schools are similar to remedi

ation programs and to the types of ancillary relief ordered in

former dual systems for schools which will not be desegregated.

See. e. g. . Mil liken v. Bradle.v, 433 U.S. 267 (1977). Several

Black HMSSD biracial committee members testified that theysup-

ported the plan because of its emphasis on improving educational

attainment in these Black schools, not because they thought it

would result in desegregation (see Tr. 383 [Lawrence], 422, 425-26

[McFarlin]) .

^^See supra note 23 and accompanying text.

5Qsee. e.g.. Tr. 481-82, 819.

- 19 -

an opportunity for all segments of the school community to have

access to the magnet schools" (R. 538^ R.Exc. 99 [p. 15]). But

the projections indicate that students from one school, Bethune,

are anticipated to fill 90 of the 96 seats reserved for non-Wal

thall and non-Jones area Black pupils in the magnet schools

(Tr. 239). Superintendent Walker testified that these projec

tions, identical to those included in the magnet plan recommended

by Dr. Winecoff and Dr. Joiner (Tr. 157-58), were checked and

verified independently by HMSSD officials (Tr. 158, 259-60) —

and that the assumption that few Black students from schools other

than Bethune, Jones or Walthall would want to attend the magnets

was based upon HMSSD school authorities' judgment (s^ Tr. 239-50) .

However, ex-Superintendent Spinks (who held his official posi

tion at the time the District Alternative plan was filed with

the district court) said that the figure of 90 Bethune pupils

attending the magnet schools was a "guess" (Tr. 124-25) , while

Dr. Joiner testified that no matter what the figures on the chart

were, it had not been his or Dr. Winecoff's assumption that only

Black students from Bethune would want to attend the magnet schools

(Tr. 462). Unable to support or explain his figures. Dr. Joiner

finally agreed that the projections do not "provide a reliable

method for estimating what the racial composition of all of the

schools in the system will be if this plan is implemented" (Tr.

468) 51

^^Dr. Winecoff testified, "Now, the chart that has been so debated was never set up and intended to be a specific-- I guess

what we'd call a traditional school district desegregation chart"

(Tr. 812). He also revealed that he and Dr. Joiner received an

original written set of projections from the HMSSD Superintendent

- 20 -

The government's expert witness, Dr. Rossell, also refused

to accept the projections submitted with the plan because she

found them to be "incomplete, or in error, or unrealistic" (R.

613, R.Exc. 157 [G-X 2, p. 16]; £££Tr. 556, 57 0 ) . For example,

she could not agree with the estimates of large increases in ma

jor ity-to-minority transfers in light of their modest use in the

past (Tr. 556).^^ She also felt that Eureka would not attract

white kindergarten pupils (Tr. 613, R.Exc. 157 [G-X 2, p. 16]).

Although she was "not quite sure whether I made the right adjust

ments" she "made cuts in virtually every school district projec

tion̂ ' (Tr. 556 ). The '"adjustments" to the projections which she

included in her written report, however, did not reflect correc

tions made by the school district's witnesses at trial (Tr. 618;

see Tr. 158-61)

and Transportation Director before they prepared their plan (Tr.

507). Although Transportation Director Goodbread did not advert

to his role in preparing the projections when he testified, he di

suggest that they might not be fully accurate (Tr. 349 50).

^^The United States did, nevertheless, support the magnet

plan as a co-signatory to the September 4 , 1985proposed consent decree (R. 520; R. 524, R.Exc. 85) --which in

eluded the projections prepared by the school district (R. 558,

R.Exc. 119; see R.Exc. 124 [D-X 33]).

^^See supra note 13.

54j-jj-̂ gtolee's projections of enrollment under his pairing

and clustering plan were also questioned because of his assumption

(R. 370, R.Exc. 133 [PI-X 24, p. 8]) that the base year enroll

ments in each school were equally divided among grades (§^ Tr.

67 0). However, Dr. Stolee testified that he had reviewed the

projections against actual grade-by-grade enrollments, subsequent

to submission of his plan, and that he concluded the more precise

figures would result in no significant change, although they would

permit a more even distribution of grades in the paired and clus

tered schools (Tr. 721, 779-80; s ^ Tr. 760-66).

- 21 -

The district court, in its Memorandum Opinion and Order, char

acterized the projections as "obviously flawed because of the

inability to anticipate exactly what choices will be made" but

suggested they were adeguate "to demonstrate that the [magnet]

plan should lead to more fully desegregated schools in Hattiesburg

[than at present]" (R. 715-16, R.Exc. 75-76 [Mem. Op. 13-14]).

Dr. Rossell also attempted to estimate the effect of "white

flight" on post-implementation school enrollments under both the

magnet plan and the Stolee plan. To do so, she reduced the white

enrollments at individual schools, as shown on Dr. Stolee's pro

jections and on her "adjusted" projections under the magnet plan,

by her "expected white enrollment loss based on my research in

other school districts" (Tr. 560). Dr. Rossel1 purported to esti

mate white enrollment declines that would occur in each of the

first two years following implementation of the Stolee plan (Tr.

641)^^ but in her analysis of the magnet plan, she "collapsed" the

"first-year effects" "into the second year,"^® and assumed full

57enrollment in the magnet schools immediately upon implementation.

See inf ra note 86.

^^HMSSD also presented evidence of white enrollment declines

in the Laurel school system in the years following implementation

of a pairing plan after this Court's remand in ynjted States

V. Mississippi [Laurel Mun. Separate School Dist.], 567 F.2d 1276

(5th Cir. 1978). S ^ D-X 4, 44, 65; Tr. 783-800.

^®Dr. Rossell testified, "Now what difference is this going

to make I don't know" (Tr. 641) and also that "I'm trying to re

member the rationale here. I simply can't." (Tr. 642.)

5'̂ See R. 6 26, R.Exc. 170 [G-X 2, p. 28] [with "Rossell adjust

ments," Jones and Walthall are each projected to enroll 120 Black

and 120 white students].

- 22 -

The projections for the Stolee plan and the magnet plan, both

as they were originally submitted and as they were recalculated

by Dr. Rossell, are collected in Table 3, infra pp. 7a-8a.

Summary of the Argument

I

An acceptable plan to end the vestiges of the dual biracial

system of education must eliminate one-race schools to the greatest

extent feasible. Even a single all-Black school remaining in an

otherwise reasonably integrated district is impermissible if a

workable alternative (which may include devices such as pairing

or noncontiguous attendance zoning) exists.

The plan approved below is limited in its scope and effective

ness. Under it, four schools will remain virtually all-Black in

1986-87. Starting in 1987-88, two of these facilities will be

converted to "magnet schools" which by 1989-90 are projected to

house 120 Black and 120 white students each. Bethune and Eureka,

however, enrolling one-third of all Black elementary students,

will continue to be virtually all-Black until the court order is

modified after the 1989-90 school year — with Eureka doubling

its current all-Black enrollment — unless white pupils exercise

majority-to-minority transfers (something which has never occurred

in the past). There is no realistic expectation of significant

voluntary white enrollment at either school, even with the initi

ation of an Extended Day program at Bethune, especially in light

of the fact that the HMSSD Black schools presently have the lowest

- 23 -

test scores (which the district advances as the justification

for creating special programs to improve Basic Skills instruction

at Eureka, Bethune and Love).

In contrast, the pairing and clustering plan proposed by

Dr. Stolee would achieve "the greatest possible degree of actual

desegregation," Swann. 402 U.S. at 26, integrating every school.

Its implementation is completely feasible; the district court

made no finding to the contrary. Under these circumstances, the

court was required by controlling precedent to order implementation

of the more effective Stolee plan.

II

The Supreme Court and this Court have made clear that further

delay in dismantling dual school systems is unacceptable. By

allowing four full school years to pass, following the evidentiary

hearing, before it will seek to evaluate the success of HMSSD's

"magnet schools" in drawing sufficient voluntary white enrollment,

and by announcing that it will not consider, much less order,

any steps to integrate Eureka and Bethune elementary schools until

that time, the district court has denied the constitutional rights

of HMSSD's Black children to attend desegregated elementary schools

in a unitary system, and its judgment must be reversed.

III

The primary justification urged by HMSSD and the United

States, and accepted by the district court, for the "magnet plan"

was the belief that implementation of a pairing and clustering

plan would cause greater "white flight" from the district. The

- 24 -

"magnet plan" seeks to minimize such flight by avoiding any reas

signment of white students to Eureka or Bethune and by limiting

Black enrollment in the magnet schools to create a racial mix

"more attractive to the white community," in the Superintendent's

words. Under well-settled principles this justification is inade

quate as a matter of law.

The "white flight" argument is no more persuasive or tenable

when it is couched in statistical measures of interracial contact,

as proposed by the government's expert witness, for it disregards

the requirement of Scotland Neck, Swann, Davis, Alexander, and

Carter that the greatest amount of actual desegregation must be

achieved without delay, subject only to limitations of practicality

and feasibility and unencumbered by speculation about future demo

graphic events.

IV

Magnet schools may be a permissible option as part of a manda

tory desegregation plan which promises to be fully effective in

eliminating the vestiges of the dual system, and the educational

improvements and incentives devised by HMSSD can and should be

carried out in conjunction with a constitutionally acceptable,

mandatory student reassignment plan.

- 25 -

ARGUMENT

Introduction

This case is governed by well settled principles enunciated

and applied in numerous rulings of the United States Supreme Court

and of this Court. Indeed, the applicable law has been so often

restated and summarized by this Court, so concisely and compel-

lingly, that no efforts by counsel could improve upon the language

of its decisions.

We, therefore, respectfully submit that it is most appropri

ate to begin this Argument by quoting from this Court's recent

opinion in Davis v. East Baton Rouge Parish School Board, 721

F.2d 1425 (5th Cir. 1983), which recounts the applicable constitu

tional requirements:

1. The burden is on the school board to justify the continu

ation of any one-race schools on grounds of practicality (721

F.2d at 1434):

Swann places the burden squarely on the Board to demon

strate that the remaining one-race schools are not ves

tiges of past segregation. 402 U.S. at 26; Tasby [ŷ

Wright) III. 713 F.2d [90,] at 94 [(5th Cir.1983)].

If further desegregation is "reasonable, feasible and

workable," Swann. 402 U.S. at 31, then it must be under

taken, for the continued existence of one-race schools

is constitutionally unacceptable when reasonable alter

natives exist. Ross [v. Houston Independent School

District). 699 F.2d [218,] at 228 [(5th Cir. 1983)];

Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Board, 566 F.2d 985,

987 (5th Cir. 1978); Swann. 402 U.S. at 26 (requi

ring "every effort to achieve the greatest possible

degree of actual desegregation").

2. Until a unitary system has been achieved, the board's

obligation encompasses the desegregation of racially isolated

schools affected by oost-Brown changing demographic patterns (721

- 26 -

F.2d at 1435-36):

Until it has achieved the greatest degree of desegrega

tion possible under the circumstances, the Board bears

the continuing duty to do all in its power to eradicate

the vestiges of the dual system. That duty includes

the responsibility to adjust for demographic patterns

and changes that predate the advent of a unitary sys

tem. Lee V. Macon Countv Board of Education, 616 F.2d

805, 810 (5th Cir. 1980); United States v. Board of

Education of Valdosta. 576 F.2d 37 , 38 (5th Cir.), cert.

denied. 439 U.S. 1007 (1978). The racial isolation of

some schools, whether existing before or developing

during the desegregation effort, may render disestab

lishment of certain one-race schools difficult or even

impossible. Until all reasonable steps have been taken

to eliminate remaining one-race schools, however, ethnic

housing patterns are but an important factor to be con

sidered in determining what further desegregation can

reasonably be achieved; they do not work to relieve the

Board of its constitutional responsibilities. Valiev

(v. Rapides Parish School Board! I, 646 F.2d [925,] at

9 37 [ (5th Cir. 1981) , cert, denied, 4 55 U.S. 939 (198 2) ].

. . . [U]ntil it can show that all reasonable steps

have been taken to eliminate remaining one-race schools,

the Board must in its pursuit of a unitary system res

pond as much as reasonably possible to patterns and

changes in the demography of the [jurisdiction].

3. Desegregation may not be delayed or diluted because of

fears or predictions of "white flight" (721 F.2d at 1436):

The Board also urges a finding of unitariness on the

familiar ground that desegregation of the remaining

one-race schools, over half the schools in the [system],

would drive families from the [system] and white chil

dren from its public schools. This is not a case like

Ross V. Houston Independent School District. 699 F.2d

218 (5th Cir. 1983), or Calhoun v. Cook, 522 F.2d 717

(5th Cir.) , reh' o denied. 525 F.2d 1203 (5th Cir. 197 5),

in which residential patterns, population migration,

or the departure of white students from the system ren

dered further desegregation of one-race schools unfeas

ible. Rather, this is a case in which by 198[5] the

desegregation of the public schools had simply not yet

been achieved. The Board's legitimate fear that white

students would depart the public school system during

the difficult period of active desegregation was cause

for "deep concern" and creative solutions but could not

justify a retard in the process of dismantling the dual

system. United States v. Scotland Neck City School

Board. 407 U.S. 484, 490-91 (1972).

- 27 -

4. Concern over "white flight" may justify special steps to

make desegregated schools attractive to white students but only

in the context of otherwise permissible, effective desegregation

plans (721 F.2d at 1438 [emphasis in original]):