James v. California Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 3, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. James v. California Brief Amicus Curiae, 1971. 2319521a-ac9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/57f9d59e-e5b3-4e99-a0c3-ab56f9092c1b/james-v-california-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

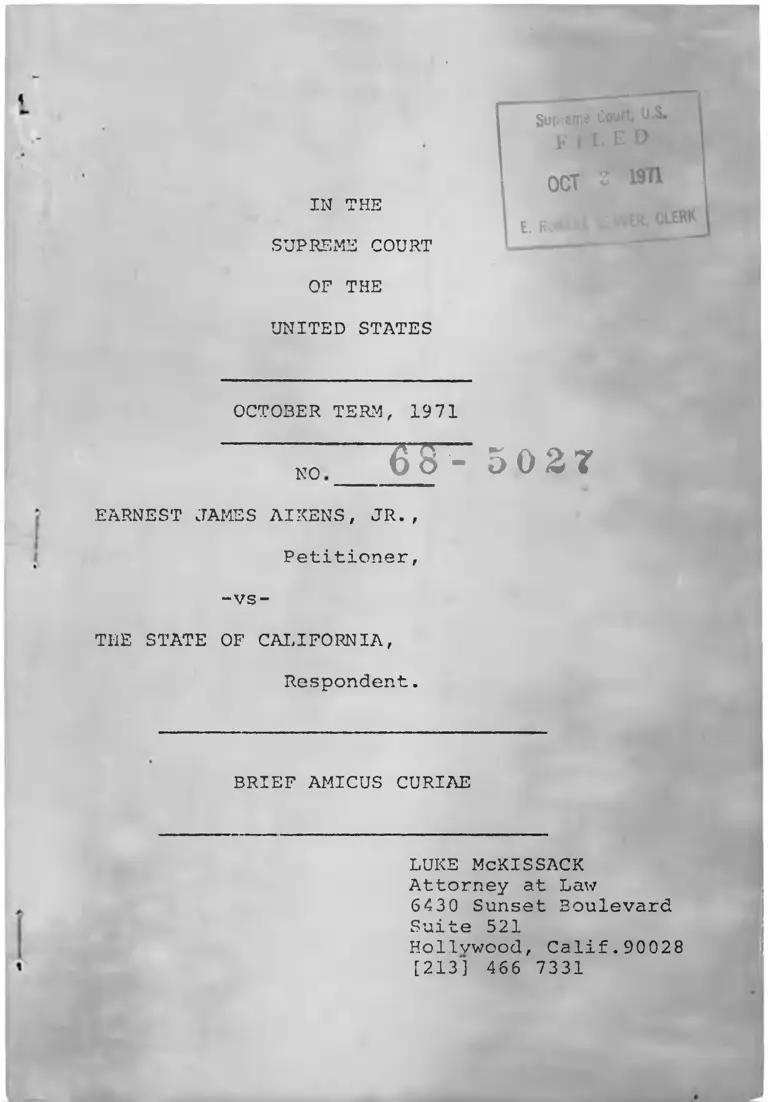

IN THE

E . RO

Supreme Court

F l 1- E

OCT 3

SUPREME COURT

OF THE

UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1971

NO BIT1’ 5 0 2 7

EARNEST JAMES AIKENS, JR.,

Petitioner,

-vs-

THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA,

Respondent.

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

LUKE McKISSACK

Attorney at Law

6430 Sunset Boulevard

Suite 521

Hollywood, Calif.90028

[213] 466 7331

IN THE

SUPREME COURT

OF THE

UNITED STATES

OCTOBER TERM, 1971

NO.________

EARNEST JAMES AIKENS, JR.,

Petitioner,

-vs-

THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA,

Respondent.

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE

LUKE McKISSACK

Attorney at Law

6430 Sunset Boulevard

Suite 521Hollywood, Calif.90028

[213] 466 7331

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES............ i

PREFACE ............ vi

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE:

I. PETITIONER IS SUBJECT TO

CRUEL AND UNUSUAL PUNISHMENT

IN VIOLATION OF THE EIGHTH

AND FOURTEENTH AMENDMENTS TO

THE UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION

____ BY BEING SENTENCED TO DEATH

FOR THE CRIME OF MURDER. TO

WIT, THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA

IN IMPLEMENTING THOSE PENAL

OBJECTIVES IT DEEMS LEGITIMATE

CAN DO SO BY MEANS LESS SUBVER

SIVE OF THE RIGHT TO LIVE -

NAMELY BY SENTENCING PETITIONER

TO LIFE IMPRISONMENT. . . -1-

CONCLUSION -14-

APPENDIX

California Penal Code

§§190 and 190.1 A-l

Letters of Consent B-l

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

PAGE

Bates v. Little Rock

361 U.S. 516,524

80 S.Ct. 412,417 (1960)

In re Anderson

69 Cal.2d 613,629

73 Cal.Rptr.21,33 (1968)

In re Estrada

63 Cal.2d 740,745

48 Cal.Rptr.172,176 (1966)

Jackson v. Bishop

(8th Cir. 1968)

404 F .2d 571

N.A.A.C.P. v. Dutton

371 U.S. 415,438-444

83 S.Ct. 328,340-343 (1963)

Parrish v. Civil Service Commission

66 Cal.2d 260,271

57 Cal.Rptr.623 (1967)

People v. Bickler

57 Cal.2d 788,793

22 Cal.Rptr, 340 (1962)

People v. Daniels

71 Cal.2d 1119,

80 Cal.Rptr. 897 (1969)

People v. Kidd

56 Cal.2d 759,770

16 Cal.Rptr.793 (1961)

Peoole v. Lane

56 Cal.2d 773,736

16 Cal.Rptr.801 (1961)

2

4,8

8

4,5,6,11

2

2

10

3

10

10

1

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

PAGE

People v. Love

56 Cal.2d 720,731

16 Cal.Rptr.777,782-783 (1961) 8

Powell v. Texas 392 U.S. 514

88 S.Ct. 2145 (1968) • 5

Robinson v. California

370 U.S. 660

82 S.Ct. 1417 (1962) ' 5

Rudolph v. Alabama

375 U.S. 889

84 S.Ct. 155,156 (1963) 4,6

Sherbert v. Verner

374 U.S. 398,404,fn.6,406

83 S.Ct. 1790,1794,fn.6,1795 2

Thomas v. Collins

323 U.S. 516,530

65 S.Ct. 315,323 (1945) 2

Trop v. Dulles

356 U.S. 86,100

78 S.Ct. 590 (1958) 6

Weems v. United States 217 U.S.■349

30 S.Ct. 544 (1910) 5

Wilkerson v. Utah

99 U.S. 130 (1878) 7

ii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

PAGE

STATUTES

CALIFORNIA PENAL CODE:

§37 12

§128 12

§129 12

§4500 12

§190 13

§190.1 13

OTHER

Borchard,

Convicting the Innocent (1932) 3

Dann, Robert H.

"The Deterrent Effect of Capital Punishment"Friends Social Service Series

Bulletin No. 29 (1935) 10

Ehrmann, Herbert B.

"The Death Penalty and the

Administration of Justice"

Annals of the Academy of Political

& Social Science

284:73-84, November, 1952 12

Frank & Frank

Not Guilty (1957) 3

iii

r

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

PAGE

Hartung, Frank E.

On Capital Punishment

Detroit; Wayne University

Dept, of Sociology & Anthropology1951, p.22 3

Lawes, Lewis L.

Twenty Thousand Years in Sing Sing

New York: R. Long & R.R. Smith

1932, pp.146-147,156 3

O'Hara, Charles E. &

Osterburg, James W.

"Some Miscarriages of Justice Analyzed

in the Light of Criminalistics"

Chapter 47 of An Introduction to

Criminalistics

New York; MacMillan, 1949, pp.680-685 3

Poliak, Otto

"The Errors of Justice"

Annals of the American Academy

of Political & Social Science

284:115-123, November, 1952 3

Schuessler, Karl F.

"The Deterrent Influence of the Death Penalty"

Annals of the American Academy

of Political & Social Science

284: 54-62,November, 1952 10

Sellin, Thorten

"Common Sense and the Death Penalty"

Prison Journal

October, 1932, p.12 10

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Sutherland & Cressey

Principles of Criminology

(5th Ed.1955), pp.292-295, 297

Void, G. B.

"Can the Death Penalty Prevent Crime?

The Prison Journal

October 1932, pp.3-8

PAGE

3,10

10

PREFACE

The presentation of this Amicus Curiae

brief on behalf of Petitioner Aikens is generated

by the fact that counsel represents two inmates

on California's death row - Sirhan Sirhan and

Jesse James Gilbert - plus one who has spent

eleven years there and is currently awaiting

his fifth death penalty retrial, Doyle Alva

Terry. All of these persons stand to be

gravely affected by this Court's decision in

Aikens.

Previously, counsel filed an Amicus Curiae

brief in McGautha v. California, 91 S.Ct. 1454

(1971). Finally, counsel has presented briefs

and made arguments against the death penalty in

cases for many years.

I

PETITIONER IS SUBJECT TO CRUEL AND

UNUSUAL PUNISHMENT IN VIOLATION OF

THE EIGHTH AND FOURTEENTH AMENDMENTS

TO THE UNITED STATES CONSTITUTION BY

BEING SENTENCED TO DEAT I FOR THE CRIME

OF MURDER. TO WIT, THE STATE OF

CALIFORNIA IN IMPLEMENTING THOSE PENAL

OBJECTIVES IT DEEMS LEGITIMATE CAN DO

SO BY MEANS LESS SUBVERSIVE OF THE

RIGHT TO LIVE - NAMELY BY SENTENCING

PETITIONER TO LIFE IMPRISONMENT.

Petitioner is under sentence of death

which will result in his execution if this

Court does not intervene to prevent it. It

is the position of Amicus Curiae that in our

system of justice life is sacred and indispen

sable to the enjoyment of all other rights

guaranteed us under the Constitution. To

interfere with such fundamental liberties,

the State of California must show a "compelling

- 2 -

need" to exterminate Petitioner in order to

effectuate the defensible purposes of the

criminal law. As this Court declared in

Bates v. Little Rock, 361 U.S. 516,524, 8Q

S.Ct. 412,417 (1960),

"Where there is a significant

encroachment upon personal liberty,

the State may prevail only upon showing

a subordinating interest which is

compelling.

The loss of life indisputably involves the loss

of all liberties, and, thus, capital punishment

remains the most far-reaching encroachment on

personal liberty known to man. Therefore, a

penalty as final as death—^ is allowable only

if those defensible purposes of the criminal

17 See also, Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S.398,

404 ,fn. 6,406 , 83 S.Ct. 1790,1794,fn.6,1795 (1963)

Thomas v. Collins,323 U.S.516,530, 65 S.Ct.315,

323 (1945); N.A.A.C.P. v. Dutton, 371 U.S.415,

438-444, 83 S.Ct.328,340-343 (1963); Parrish v.

Civil Service Commission,66 Cal.2d260,271, 57 Cal

Rptr.623 (1967) .

2/ When the death sentence is meted out, effectively a class of persons is created who cannot

receive the benefits of future changes in the

-3-

law can be vindicated by no alternative means

less subversive of the right to live. Otherwise,

the State of California will have inflicted the

loss of life without any commensurate justifi

cation. This argument we now proceed to analyze.3/

law which may accrue to their benefit such as

the declaring of the "Little Lindbergh Law"

unconstitutional which would have saved the

life of Chessman were he still living at the

time of the decision. [See People v. Daniels,

71 Cal.2d 1119, 80 Cal.Rptr. 897 (1969).

Moreover, it denies the ameliorative prospects

of legislative change in the form of legalizing

the formerly condemned behavior or diminishing

the penalty; finally, prospects for future proof

of innocence and pardon disappear with the defen

dant's execution. And innocence subsequently

discovered is not foreign to our system of

justice. See cf., Frank & Frank, Not Guilty,

(1957); Borchard, Convicting the Innocent (1932).

Sutherland & Cressey, Principles of Criminology

(5th Ed.1955),p.297; Charles E. O'Kara & James

W. Osterburg, "Some Miscarriages of Justice

Analyzed in the Light of Criminalistics", Chapter

47 of An Introduction to Criminalistics (New York;

MacMillan,1949),pp.680-685; Lewis L. Lawes, Twenty

Thousand Years in Sing Sing,(New York: R.Long &

R.R. Smith,1932),pp.146-147,156; Frank E. Hartung,

On Capital Punishment, Detroit; Wayne University

Dept, of Sociology & Anthropology,1951,p.22; Otto

Poliak, "The Errors of Justice",Annals of the

American Academy of Political & Social Science,

284:115-123/November, 1952. Imprisonment keeps all

of these possibilities viable. It may be that a

person while in prison will die a natural death or

no change will ensue but that is not a state re

sponsibility. What is directly attributable to the

death penalty is the eternal ineligibility for

relief that is denied to no other prisoner.

4-

The two cardinal manifestos of the American

political and jurisprudential conscience, the

Declaration of Independence and the United States

Constitution, embody the precept that life is a

most precious commodity. The Declaration of

Independence proclaims that our Government is

indeed formed to guarantee certain inalienable

rights, most_notably "life, liberty and the

pursuit of happiness". The Fifth Amendment to

the United States Constitution provides that no

person may "be deprived of life, liberty or

property without due process of law". In both

documents, man's life is not only the first

named, but the most eminent concern of the State.

"37 While this type of inquiry is cast in due

process terms and is not coextensive with the

phrase "cruel and unusual" punishment, the two

have routinely been intertwined in the analysis

of appellate courts. See e.g., Rudolph v. Alabama,

'375 U.S. 889, 84 S.Ct. 155,156 (1963); Jackson v.

Bishop (8th Cir.1968) 404 F .2d 571; In re Anderson,

69 Cal.2d 613,629, 73 Cal.Rptr.21,33 (1968).

-5-

It has been held since time immemorial that

the State's right to punish, much less kill,

cannot be based on whim or caprice. Weems v.

United States, 217 U.S. 349, 30 S.Ct. 544 (1910).

It cannot punish a man at all for his addiction

to drugs [Robinson v. California, 370 U.S. 660,

82 S.Ct. 1417 (1962)], or for acquiring a common

cold [ibid;667], or for simply being an alcoholic

[cf. Powell v. Texas, 392 U.S. 514, 88 S.Ct.

2145 (1968)]. Furthermore, even the type of

penalty is subject to considerable restraint.

For example, it has been held that whipping is

an impermissible punishment [Jackson v. Bishop,

supra]. Thus, there is ample precedent for re

quiring the State to demonstrate a legitimate

basis for the punishment imposed. Moreover,

punishments far less severe and final than that

sought to be imposed here have been ruled viola

tive of the Cruel and Unusual Punishment provi

sion in the Constitution. See Jackson v. Bishop,

- 6 -

supra, cases cited at p.580.—■̂

Chief Justice Warren declared for four

members of this Court in Trop. v. Dulles, 356

U.S. 86,100, 78 S.Ct. 590 (1958):

"This Court has had little occasion

to give precise content to the Eighth

Amendment."

and, in observing that its contents were not

fixed, commented,

" . . . [the Eighth Amendment] must draw

its meaning from evolving standards of

decency that mark the progress of a

maturing society." [Ibid,at 101; see

also Rudolph v. Alabama,supra, at p.889;

Jackson v. Bishop,supra, at 579.]

The Chief Justice finally noted that the basic

concept enshrined in the Eighth Amendment was

"nothing less than the dignity of man".

47 It stands to reason that if an adequate

State interest is required to render conduct

criminal, that an adequate State interest

is needed to justify the punishment also.

-7-

Thus, although capital punishment has been

regarded by this Court previously [Wilkerson

v. Utah, 99 U.S. 130 (1878)] as not violative

of the Cruel and Unusual Punishment clause,

this society's maturation, attested to by

the lack of a single execution since June 2,

1967, and the preservation of over 700 persons

who are under sentence of death, commands that

the question be considered anew.

The right of the State of California to

punish those who commit murder is beyond question

But since the infliction of the death penalty

is grave and irremediable, it is essential that

we examine those purposes of the criminal law

deemed justifiable by that State (California)

in penalizing those who perpetrate crimes,in

order to ascertain whether the State can demon

strate a "compelling interest" in retaining

the death penalty for homicide.

It is clear that California does not

regard vengeance or retribution as a permissible

- 8 -

basis for incarceration or execution. In re

Estrada, 63 Cal.2d 740,745, 48 Cal.Rptr.172,

176 (1966). As the Court stated therein:

"There is no place in the scheme

for punishment for its own sake, the

product of vengeance or retribution."

[See Michael & Wechsler on"Criminal Law and

Its Administration" (1940), pp.6-11; Note,55

Col.L.Rev.,pp.1039,1052; see also, In re

Anderson,supra, at 630.]

This leaves then, as the potentially

proper functions of punishment, isolation,

rehabilitation and deterrence. Of those,

California has also ruled out deterrence as

a permissible basis for administering the

death penalty. As the California Supreme

Court stated in People v. Love, 56 Cal.2d 720,

731, 16 Cal.Rptr.,777,782-783 (1961),:

"Prosecutors have often stated

that it is necessary swiftly and

-9-

severely to punish the guilty, and

such statements have usually been con

sidered within the bounds of proper

argument . . .In the present case, however,

the prosecutor went beyond merely using

severe punishment. He stated as a fact

the vigorously disputed proposition

that capital punishment is a far more

effective deterrent than imprisonment.

The Legislature has left to the absolute

discretion of the jury the fixing of the

punishment for first degree murder. . .

There is thus no legislative finding,

and it is not a matter of common know

ledge, that capital punishment is or is

not a more effective deterrent than im

prisonment. Since evidence on this question

is inadmissible, argument thereon by the

prosecution or defense could serve no use

ful purpose, is apt to be misleading, and'

II

- 10-

is therefore improper.

(See also, People v. Bickler,57 Cal.2d 788,793,

22 Cal.Rptr, 340 (1962); People v. Lane, 56 Cal.

2d 773,786, 16 Cal.Rptr.801 (1961); People v.

Kidd, 56 Cal.2d 759,770, 16 Cal.Rptr. 793 (1961).)

The body of authorities shattering the

myth that the death penalty acts as a deterrent

is enormous.!/ Suffice it to say, as in the

case of revenge, California has decided that the

death penalty is not warranted as a deterrent

to murder. Thus, the permissible foundations

for criminal penalties which remain are isolation

and rehabilitation. To state that a murderer

may be isolated from society through incarceration

57 Thorten Sellin, "Common Sense and The Death

Penalty", Prison Journal, October,1932, p.12;

Sutherland & Cressey, Principles of Criminology,

(5th Ed.1955),pp.292-295; Karl F. Schuessler,

"The Deterrent Influence of the Death Penalty",

Annals of the American Academy of Political &

Social Science; 284:54-62, November, 1952. G.B.

Void, "Can the Death Penalty Prevent Crime?",

The Prison Journal, October 1932,pp.3-8; Robert

H. Dann, "The Deterrent Effect of Capital Punish

ment" , Friends Social Service Series, Bulletin.

No. 29, 1935.

- 11-

is to state an evident tautology. And the

number of criminals who are capable of being

rehabilitated through the death penalty is

none,^/ thus the State of California does not

have a "compelling interest" in obtaining

Petitioner's death.

Lest it be contended that execution is

more economical— than life imprisonment, we

summon forth the stern admonition of Mr. Justice

Blackmun in Jackson v. Bishop, supra. In declar

ing whipping to be violative of the Cruel and

Unusual Punishment provision, he resolved that:

"We are not convinced contrarily by

any suggestion that the State needs this

tool for disciplinary purposes and is

too poor to provide other accepted means

of prisoner regulation. Humane considera

tions and constitutional requirements are

not, in this day, to be measured or limited

by dollar considerations or by the thickness

67 Even those persons having profound religious

convictions must surely concede that the

number of resurrections appears to be minimal.

- 12-

of the prisoner's clothing[at p.580.]—'

Although it is clear that the State cannot justi

fy killing members of its population to avoid

a budget increase, the swelling number of

prisoners on death row, the lengthy nature of

appeals, etc., suggest that it is actually more

expensive to execute a man than to incarcerate

him for life..§/

It is also worthy of note that the State

of California has little trouble expressing

itself when it deems specified behavior deserv

ing of the death penalty. For four separate

crimes, the California legislature has dictated

that result..9/ In other cases, the matter

is left up to the jury without guideposts to

77 It is not necessary here to detail the various

arguments against the death penalty such as the

State, the "omnipresent teacher", using the death

penalty to cheapen the respect for human life.

8/ Herbert B. Ehrmann, "The Death Penalty and

the Administration of Justice," Annals of the

Academy of Political & Soc.ial Science, 284:73-84,

November, 1952.

9/ Treason [Calif.Pen.Code§37] ; Perjury procuring

an innocent's death [Calif.Pen.Code§128]; Train

wrecking with bodily harm [Calif.Pen.Code §219],

Assault by a lifer causing death of a non-inmate

[Calif.Pen.Code§4500] .

-13-

make an appropriate determination Thus,

the State of California, which has survived

without an execution since April 12, 1967,

has not asserted a "compelling interest" in

exacting a human life as the penalty for murder.

As explained above, the purposes of the criminal

law are satisfactorily effectuated by life

imprisonment - a means less subversive to the

right to live. California has shown no

"compelling interest" which would warrant

rendering Petitioner extinct.

107 Calif.Pen. Code §§190 and 190.1.

-14-

CONCLUSION

Petitioner's sentence of death should

be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

J/! <An

/-UCUt

y

/ A <rJ-LUKE McKISSACK

Amicus Curiae in support

of Petitioner

APPENDIX

1

APPENDIX

California Penal Code, Section 190:

MURDER; PUNISHMENT; DISCRETION OF JURY

Every person guilty of murder in the first

degree shall suffer death, or confinement in

the state prison for life, at the discretion

of the court or jury trying the same, and the

matter of punishment shall be determined as

provided in Section 190.1, and every person

guilty of murder in the second degree is

punishable by imprisonment in the state prison

from five years to life.

California Penal Code, Section 190.1:

SENTENCES OF DEATH OR IMPRISONMENT

FOR LIFE; DETERMINATION: MINORS UNDER 18

The guilt or innocence of every person

charged with an offense for which the penalty

is in the alternative death or imprisonment

for life shall first be determined, without

a finding as to penalty. If such person has

been found guilty of an offense punishable by

1 i f *=> i m n r i c n r i m o n f -N ~ J T--

A-2

sane on any plea of not guilty by reason of

insanity, there shall thereupon be further

proceedings on the issue of penalty, and the

trier of fact shall fix the penalty. Evidence

may be presented at the further proceedings

on the issue of penalty, of the circumstances

surrounding the crime, of the defendant's

background^and history, and of any facts in

aggravation or mitigation of the penalty. The

determination of the penalty of life imprison

ment or death shall be in the discretion of

the court or jury trying the issue of fact on

evidence presented, and the penalty fixed shall

be expressly stated in the decision or verdict.

The death penalty shall not be imposed, however,

upon any person who was under the age of 18

years at the time of the commission of the

crime. The burden of proof as to the age of

said person shall be upon the defendant.

If the defendant was convicted by the court

sitting without a jury, the trier of fact shall

A-3

be the court. If the defendant was convicted

by a plea of guilty, the trier of fact shall

be a jury unless a jury is waived. If the

defendant was convicted by a jury, the trier

of fact shall be the same jury unless, for

good cause shown, the court discharges that

jury in which case a new jury shall be drawn

to determine the issue of penalty.

In any case in which defendant has been

found guilty by a jury, and the same or

another jury, trying the issue of penalty,

is unable to reach a unanimous verdict on

the issue of penalty, the court shall dismiss

the jury and either impose the punishment for

life in lieu of ordering a new trial on the

issue of penalty, or order a new jury impaneled

to try the issue of penalty, but the issue of

guilt shall not be retried by such jury.

S T A T E O F C A L I F O R N I A

OFFICE OF THE ATTORNEY GENERAL

Uqjartnmtt of fcsttrr

S T A T E B U I L D I N G . L O S A N G E L E S 9 0 0 1 2

217 Vest First St.

August 27 > 1971

Luke McKissack, Esq.

64-30 Sunset Blvd., Suite 521

Los Angeles, California 90028

R e : Aikens v. California

68-5027

Dear Mr. McKissack:

In accordance with, previous oral

representations made to you, respondent in

the above matter hereby gives its consent

to your filing a brief amicus curiae in this

case.

RMG:jd

Very truly yours,

EVELLE J. YOUNGER, Attorney General

By

Deputy Attorney General

RONALD M. GEORGE

APPENDIX B-l

cc: Anthonv G. AmafaTrlflim Eon

STANFORD L A W SCHOOL

S ta nfo rd , C a lifo rn ia 94305

August 30, 1971

AIR MAIL-SPECIAL DELIVERY

Luke McKissack, Esq.

6430 Sunset Boulevard, Suite 521

Los Angeles, California 90028

Ij

re• Aikens v. California

O.T. 1971, No. 68-5027

|Dear Mr. McKissack:

i

i

Pursuant to Rule 42(2), I am pleased to conse

on^behalf of petitioner Aikens to your filing a brie

£££.iae in this matter. I understand that you w

be unable to have the brief filed cn the due date and

no objection to its late filing.

Sincerely,

V

AGA:mh Anthony G. Amsterdam

Hi 3

STANFORD L A W SCHOOL

S ta n fo rd , C a l ifo r n ia 04305

August 30, 1971

AIR MAIL-SPECIAL DELIVERY

Luke McKissack, Esq.

6430 Sunset Boulevard, Suite 521

Los Angeles, California 90023

! • Aliens v. California

O.T. 1971, No. 68-5027

■;Dear Mr. McKissack:

Pursuant to Rule 42(2), I

on behalf of petitioner Aikens to

amicus curiae in this matter. I

be unable to have the brief filed

no objection to its late filing.

ana pleased to consent

your filing a brief

understand that you will

on the due date, and have

Sincerely,

AGA:mh Anthony G. Amsterdam