Harrison v. Dole Brief for Federal Appellants

Public Court Documents

September 28, 1983

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Harrison v. Dole Brief for Federal Appellants, 1983. ed426689-b59a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/58252321-fb46-447a-bef6-70b401081cb1/harrison-v-dole-brief-for-federal-appellants. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

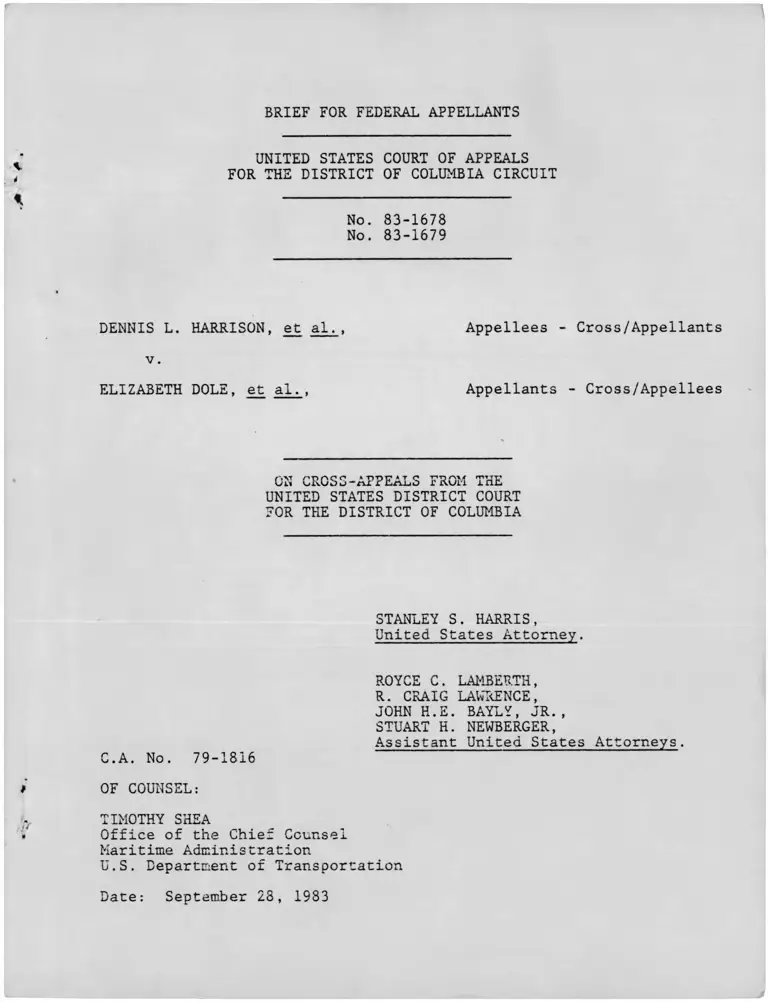

BRIEF FOR FEDERAL APPELLANTS

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 83-1678

No. 83-1679

DENNIS L. HARRISON, et al.,

v.

ELIZABETH DOLE, et al.,

Appellees - Cross/Appellants

Appellants - Cross/Appellees

ON CROSS-APPEALS FROM THE

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

STANLEY S. HARRIS,

United States Attorney.

C.A. No. 79-1816

OF COUNSEL:

ROYCE C. LAMBERTH,

R. CRAIG LAWRENCE,

JOHN H.E. BAYLY, JR.,

STUART H. NEWBERGER,

Assistant United States Attorneys.

TIMOTHY SHEA

Office of the Chief Counsel

Maritime Administration

U.S. Department of Transportation

Date: September 28, 1983

I N D E X

Page

ISSUES PRESENTED .......................................... xi

REFERENCES TO PARTIES AND RULINGS ........................ 1

STATEMENT OF THE C A S E .................................... 3

Procedural History ........................................ 3

Statement Of Facts ........................................ 9

I. Background--The Maritime Administration (MarAd). . y

A. MarAd's Organization ...................... 9

B. MarAd's Personnel System .................. 10

1. Background............................ 10

2. Competitive Promotions ................ 11

3. Competitive Promotions After December

1979 ................................ 15

4. Validation of Selection Procedures . . . 16

5. Non-Competitive Promotions ............ 16

6. Training.............................. 19

7. Awards................................ 19

8. Disciplinary Actions .................. 20

9. Reorganization........................ 21

II. The Anecdotal Evidence.......................... 21

III. The Statistical Evidence........................ 22

A. Statistical Overview ...................... 23

B. Statistical Evidence Presented by

the Class................................ 23

C. MarAd's Response .......................... 26

1. Non-Competitive Promotions ............ 27

2. Competitive Promotions ................ 29

Page

D. The Class Members' Response to MarAd's

Statistics.............................. 32

IV. The District Court's Findings and Conclusions. . . 34

A. "Compound" Class Discrimination Findings. . . 34

B. The Sex and Race Class Discrimination

Findings................................ 37

C. The Prevailing Class Relief ............... 40

D. The Individual Claims...................... 42

SUMMARY OF THE A R GUMENT................................... 42

ARGUMENT.................................................. 45

I. The District Court Erred In Certifying the

Compound, Across-the-Board Class ............... 45

A. Introduction.............................. 45

B. Class Actions and Title V I I ................ 47

C. The Prerequisites for Class Certification

(Rule 23(a)) 50

1. The Lack of Common Questions of Law

and Fact (Rule 23(a)(2)............ 50

2. The Lack of Typicality (Rule

23(a)(3)).......................... 54

3. The Inadequacy of Representation

(Rule 23(a)(4)).................... 58

a. Conflicts Between White Females

and B l a c k s .................... 58

b. Conflicts Between Black Females

and Black Males................ 60

c. Conflicts Between Applicants

and Employees.................. 60

d. Conflicts Between Supervisors and

Non-Supervisors ............... 61

-ii-

Page

e. Conflicts Involving Plaintiffs

Harrison and Spencer (EEO

Officers).................... 62

D. Improper Bifurcation of the Compound Class

After Trial (Rules 23(c)(1) and (4)(B)) . . 64

E. Summary.................................... 68

II. The District Court Erred In Finding Partial

Class Liability.............................. 68

A. The District Court Applied An Additional,

Erroneous Theory of Liability After

Rejecting The Class Claim of Compound

Discrimination .......................... 68

B. The District Court Improperly Shifted

The Burden of Proof to M a r A d ............ 71

1. Plaintiffs' Prima Facie Burden

Under Title V I I .................... 71

2. The Failure of the Class To Establish

A Prima Facie C a s e .................. 74

C. According To The District Court's Own

Findings MarAd's Rebuttal Evidence

Entitled it to Judgment................ 78

III. The District Court's Relief Order, Requiring

A Validation Study, Was Erroneous ........... 82

IV. The District Court's Relief Order, Providing

for Individual Class Claims Between August 1,

1975 and January 25, 1983, was Overbroad . . . 83

CONCLUSION................................................ 84

w

-iii-

TABLE OF CASES

Airline Stewards and Stewardesses Assoc.,

Local 500 v. American Airlines, Inc., ZT90 F.2d

636 (7th CirT 1973) cert, denied, 516 U.S.

993 (1975)...........................................64

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405,

(1975)". .. . ....................................... 74

American Pipe and Construction Co. v. Utah,

• 414 U.S. 538 ( 1 9 7 4 ) ............ 47, 68

Arnett v. American National Red Cross, 78

F.R.D. 73 (D.D.C. 1978) 62

Bachman v. Collier, 73 F.R.D. 300 (D.D.C.

1976) 51

Bachman v. Pertschuk, 437 F. Supp. 973

(D.D.C. 1977) 62

Bailey v. Ryan Stevedoring Co., Inc., 528

F .2d 551 (5th Cir. 1976) cert. denied,

429 U.S. 1052 ( 1 9 7 7 ) ............................... 59

Betts v. Reliable Collection Agency, Ltd.

659 F.2d 1000 (9th Cir. 1981) 65

Board of Trustees of Keene State College

v. Sweeney, 439 U.S. 24 (1978) ! ! ! . .............. 71

PAGE

Bostick v. Boorstin, 617 F.2d 871 (D.C.

Cir. 1980).......................................... 54-5

Brown v. General Services Administration, 425

U.S. 820 (1977) .................... ................ 78

Califano v. Yamasaki, 442 U.S. 682

(1979).............................................. 46

Cobb v. Avon Products, Inc., F.R.D. 652

(W.D. Pa. 1 9 7 6 ) .................................... 62/V /

Clark v. Alexander, 489 F. Supp. 1236 (D.D.C.

' ”19'S0) . T T T T .................................... 77

Cases chiefly relied upon are marked by astericks.

-iv-

PAGE

Croker v. Boeing Co., 662 F.2d 975 (3d Cir.

' 19STT . . . . . . ............................................................................ 72

Crown, Cork and Seal Co., Inc. v. Parker, U.S.

, 76 L.Ed.2d 628 (1983) ........................ 47, 68

y^Davis v. Califano, 613 F.2d 957 (D.C. Cir.V 197$) .............................................. Passim

Deguaffenreid v. General Motors Assemby Div.,

558 F.2d 840 (8th Cir. 1977) ......................... 70

De Medina v. Reinhardt, 686 F.2d 997

(D.C. Cir. 1982) . ................................... 49, 70

/Donaldson v. Pillsbury Co., 554 F.2d 825 (8th

\J Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 434 U.S. 856 (1977) . . . . 51

Dothard v. Rawlins on, 433 U.S. 321 (1977)............ 76

Droughn v. FMC Corp., 74 F.R.D. 639 (E.D. Pa.

1977) .............................................. 60

*East Texas Motor Freight System, Inc, v. Rodriguez,

y 431 U.S. 395 (1978) , . . .............................Passim

Edmondson v. Simon, 86 F.R.D. 375 (N.D. 111. 1980) . . 60

Eisen v. Carlisle and Jacquelin, 417 U.S. 156

(1974)............................................... 63

EEOC v. American National Bank, 652 F.2d 1176

(4th Cir. 1981), cert, denied, U.S.

103 S. Ct. 235 (1932).................................. 71

*EE0C v. Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, 698 F.2d

633 (4th Cir. 1983), cert, granted sub nom.,

Cooper v. Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, 52 U.S.L.W.

3342'"(No. 83-l'g'5)” 27, 73, 75

Feeney v. Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 475 F.

Supp. 109 (D. Mass. 1979) , art'd, 445 U.S. 901

(1980) ........................................... 59

Furnco Construction Corp. v. Waters, 438 U.S. 567

(1978) . . .....................................

General Telephone Co. v. EEOC, 446 U.S. 318

(1980) . . . . . . . ..........................

*General Telephone Co. of the Southwest v. Falcon,

457 U.S. 143 (1982) .............. ............

69, 71

49, 61

Passim

-v-

PAGE

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424

(1971).............................................. 74

/Hazelwood School Distrct v. United States, 433

'S U.S. 299 (1977) . . .................................Passim

Hill v. Western Electric Co., 596 F.2d 99 (4th Cir.

1979), cert, denied, 444 U.S. 929 (1979)............ 56, 61

Hofer v. Campbell, 581 F.2d 975 (D.C. Cir. 1978). . . . 55

Horton v. Goose Creek Independent School District,

677 F.2d 471 (5th Cir. 1982)................... 58

^International Brotherhood of Teamsters v. United

V 7 States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977) . . . ...................Passim

Inwood Laboratories, Inc. v. Ives Laboratories,

Inc., UTS: , 102 S. Ct. 2182 (1982) . . . . . . 74

In Re General Motors Corp. Engine Interchange

Litigation, 594 F.2d 1106 (7 th Cir. 1979) , cert.

denied^ 5"44 U.S. 870 (1979)........................ 65, 68

/feffries v. Harris County Action Ass'n, 615

n/ F. 2d 1025 (5th Cir. 1 9 8 0 ) .......................... 70

Johnson v. American Credit Co. of Georgia, 581

F. 2d 526 (5th Cir. 1978).......... 7 ............... 65

Johnson v. General Motors Corp., 598 F.2d 432

(5th Cir. 1979) 64

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc., 417

F. 2d 1122 (5th Cir. 1975) TT"T- T T -.............. 51

Karan v. Nabisco, Inc. 78 F.R.D. 388

(W.D. Pa. 1978) . ................................... 55

Kizas v. Webster, 707 F.2d 524 (D.C.

Cir. 1983)..................................... 78

Kramer v. Scientific Control Corp., 534 F.2d

1085 (3d Cir. 1976) , cert. denied, 429 U.S.

830 (1976) 63

-vi-

PAGE

Lo Re v. Chase Manhattan Corp., 431 F. Supp.

139 (S.D.N.Y. 1977) . . . . ........................ 57, 62

Manduiano v. Basic Veg. Prod., Inc., 541 F.2d

832 (9th Cir. 1976) . ............................... 58

Mathews v. Diaz, 426 U.S. 67 (1976).................. 56

*McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S. 792

(1973) ! ! T-! ! i . .................................Passim

Metrocare v. WMATA, 679 F.2d 922 (D.C. Cir.

1982) 7 ............................................ 73

National Association for Mental Health, Inc.

v. Califano, F.2d , Nos. 82-1196, TT97,

1278 and 1503 ("D.C. Cir. September 27, 1983) . . . . 58

NLRB v. Bell Aerospace Co., 416 U.S. 267

~TI^74).............................................. 63

NLRB v. Yeshiva University, 444 U.S. 672 (1980) . . . . 63

Patterson v. General Motors Corp., 631 F.2d

4 7 6 (7 th CirT 1980) cert, denied, 451 U.S.

914 (1981) ....................................... 57

Payne v. Travenol Laboratories, Inc., 673 F.2d

- 798 (5th Cir. 1982) , cert. denied, U.S.

, 103 S. Ct. 451 TI932) ........................ 60

Pendleton v. Rumsfeld, 628 F.2d 102 (D.C. Cir.

1980)— 7 . . 7 " . “ 7 ....................................................................................................... 63

Phillips v. Klassen, 502 F.2d 362 (D.C.

Cir. 1974).......................................... 57

Piva v. Xerox Corp., 654 F.2d 591 (9th Cir.

~ U 5 l) .............................................. 72

*Pouncy v. Prudential Ins. Co. of America, 668

F. 2d 795 (5th Cir. 1982)............. ................ 75, 78, 79

Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273,

-7 (1982) ............................................... 74

Richardson v. Byrd, 709 F.2d 1016 (5th Cir. 1983) . . . 56

-vii-

PAGE

Rivera v. City of Wichita Falls, 665 F.2d 531 (5th

Cir. 1982) ......................................

Rodgers v. United States Steel Corp., 69 F.R.D.

382 (W.D. Pa. 1975) 7 ........ T ...............

Ste. Marie v. Eastern R. Ass'n, 650 F.2d 395

(2d Cir7-1981) ..................................

Schlesinger v. Reservists Committee_ to Stop the War,

418 U.S? 208 ( T S 7 ? ) .................. ..

Segar v. Civiletti, 508 F. Supp. 690 (D.D.C.

1981), appeal pending, Nos. 82-1541 and 1590

(D.C.Cir.) ....................................

Senter v. General Motors Corp., 532 F.2d 511

(6th Cir. 1976) cert, denied, 429 U.S. 870

(1976) ........................................

Strong v. Arkansas Blue Cross and Blue Shield,

Inc., 87 F.R.D. 496 (E.D. Ark. 1980) .................

Talev v. Reinhardt, 662 F.2d 889 (D.C. Cir. 1981) . . .

Taylor v. Safeway Stores, Inc., 524 F.2d 263

(10th Cir. 1975) ....................................

*Texas Department of Community Affairs v. Burdine,

450 U.s7 248 (1982) . . . . . . . . ................

Thompson v. Sawyer, 678 F.2d 257 (D.C. Cir.

1982) ..............................................

rout v. Lehman, 517 F. Supp. 873 (D.D.C. 1981),

aff*d in part and reversed in part, 702 F.2d

1094 (D.C. Cir. 1983), cert. pet. pending,

52 U.S.L.W. 3387 (No. $ 3 ^ 7 0 6 ) ............

Tucker v. United Parcel Service, 657 F.2d 724

(5t'h Cir. 1 9 8 1 ) ............ ..............

United Airlines, Inc. v. Evans, 431 U.S. 533(1977) . . . . . . T 7 ............

*U.S. Postal Service v. Aikens, U.S. ,

103 S. Ct. 1478 (1983).....................

*Valentino v. United States Postal Service, 674

J F.2d 56 (D.C. Cir. 1982).............. .. . ,

77

62

75, 77, 79

49

25

49, 50

60

77

50, 54

Passim

41

Passim

57

83

Passim

Passim

■ V l l l -

PAGE

Wang v. Hoffman, 694 F.2d 1146 (9th Cir.

“TM3) .............................................. 76

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) ............ 74

Wetzel v. Liberty Mutual Ins. Co., 508 F.2d 239

(3d Cir. 1975), cert, denied, 421 U.S. 1011

(1975) 51, 63

Jrfilkens v. University of Houston, 654 F.2d 388

v/ (5th Cir. 1981) . ...................................53

Wilson v. Allied Chemical Corp., 456 F. Supp.

249 (E.D. Va. 1978) . . . . ......................... 56

OTHER AUTHORITIES

5 U.S.C. § 701 et s e ^ ................................. 40

42 U.S.C. § 2000e et se£ (Title VII) ................ Passim

Rule 19(a), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure ........ 40

Rule 23, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure ............ Passim

5 C.F.R. § 300.101 et seq. (1977).................... 12

§ 338.101 TT977)............................ 12

§ 713.201 et seq. (1977)..................... 78, 84

Part 772, Subpart D (1977).................. 78, 84

29 C.F.R Part 1613 (1981)............................. 78, 84

F.P.M. Ch. 315 § 1-4 (1981)........................... 1

Ch. 335 § 1-4 (1981)........................... 11

Ch. 338 § 3-1 (1981)........................... 11

0PM X-118 Qualification Standards .................... Passim

3B W. Moore's Federal Practice, K 23.05[1] (1978) . . . 63

\ 23.40 [ 4 ] .......... 50

7A Wright, Miller and Kane, Federal Practice and

Procedure, Civil § 1775 .............................. 63

§ 1790.............................. 65

-ix-

PAGE

Fisher, Multiple Regression in Legal Proceedings,

80 Col.L.Rev. 702 (1980) . . . . .......... 7 . . . . 25

Ralston, The Federal Government as Employer:

Problems and Issues in Enforcing the Anti-

Discrimination Laws-̂ 10 Ga.L .Rev. 717 (T976)........ 7a

Shoben, Compound Discrimination: The Interaction

of Race and Sex in Employment Discrimination,

55 N.Y.U.L. Rev. 793 (1980).............. .......... 70

-x-

ISSUES PRESENTED */

In the opinion of appellants, the following issues are

presented on appeal:

1. Whether the District Court erred in certifying a compound,

"across-the board" class of "all past, present and future" black

and female employees and applicants for employment at the Maritime

Administration (MarAd): (a) where the three-named plaintiffs,

and the class members they purport to represent, failed to

present common questions of law and tact; (b) where the three-

named plaintiffs, and the class members they purport to represent,

failed to present typical claims; and (c) where the three-named

plaintiffs did not adequately or fairly represent the interests

of the class members.

2. Whether the District Court erred in bifurcating the

above-described compound class into subclasses of blacks and

women after rendering its decision on the merits.

3. Whether the District Court applied an erroneous theory

of liability at trial where, once having found that plaintiffs

had failed to prove the existence of discrimination against the

above-described compound class, it nevertheless found that class

discrimination had been proven on the basis of race but not sex.

^7 These cases have not previously been before this Court and

appellants are aware of no related case before the Court. The

present cross-appeals were consolidated by the Court, sua sponte,

in an Order dated July 7, 1983.

-xi-

4. Whether the District Court improperly shifted the burden

of proof to defendants below when plaintiffs had failed to set

forth a prima facie case of either compound or racial discrimi

nation .

5. Whether the District Court erred in finding discrimina

tion against black class members when defendants' proof rebutted

any inference of discrimination.

6. Whether the District Court, in its relief order, erred

in compelling the completion of a validation study by the Maritime

Administration of selection criteria promulgated by the Office of

Personnel Management (a non-party) when those facially neutral

standards are binding on all federal agencies, including defendants,

as a matter of law.

7. Whether the District Court, in its relief order, erred

in providing for individual class claims between August 1, 1975

and January 25, 1983, when such relief was not based on the

statistical proof and was overbroad.

-xii-

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 83-1678

No. 83-1679

DENNIS L. HARRISON, et al., Appellees - Cross/Appellants

v.

ELIZABETH DOLE, et al., Appellants - Cross/Appellees

BRIEF FOR FEDERAL APPELLANTS

REFERENCES TO PARTIES AND RULINGS

Appellants are the Secretary of Transportation and the

Administrator of the Maritime Administration ("MarAd"). They are

also cross-appellees.

Appellees are three individuals, Dennis L. Harrison, Doris

J. Spencer, Janis M. Lawrence, and a class defined as "all past,

present and future Black male, Black female and White female

employees and applicants for employment at the Headquarters

Office of the United States Maritime Administration." They are

also cross-appellants.

This appeal arises out of the Honorable Louis B. Oberdorfer's

ruling against the U.S. Maritime Administration ("MarAd") in a

Title VII sex and race discrimination class action originally

brought against the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Commerce —■

and the MarAd Administrator. C.A. No. 79-1816. Judge Oberdorfer's

ruling in favor of MarAd on the sex discrimination portions of

the case and certain relief portions of the race discrimination

case are not at issue in this appeal, but are the subject of the

consolidated cross-appeal.

District Judge Oberdorfer's liability opinion was entered on

June 7, 1982 and is not reported. ("Op.") (J.A. at 198). — On

January 25, 1983, Judge Oberdorfer issued a further liability

order and "Proposed Judgment and Order" which is reported at 559

F. Supp. 943 (D.D.C. 1983), (JA at 240). Thereafter, the Court

issued its relief Order ("Injunction") on March 18, 1983. (JA at

254). Plaintiffs then filed a motion to alter or amend the

judgment of the Court, which the Court denied on April 14, 1983.

(JA at 267).

T7 Until 1981, MarAd was a primary operating unit of the Depart

ment of Commerce. In August 1981, MarAd was transferred to the

U.S. Department of Transportation, whose Secretary was then

substituted as a defendant. See P.L. 97-31.

2J "J.A." refers to the Joint Appendix in the consolidated

appeals, which will be filed after the last brief is filed. Rule

30(c), F.R.App.P. "D.Ex." refers to Defendants' Trial Exhibit.

"P.Ex." refers to Plaintiffs' Exhibit. "Tr." refers to the Trial

Court transcript. "R" refers to the docket number of the record

on appeal. "Add." refers to the statutory and regulatory Addendum

attached hereto.

2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Procedural History

On March 24, 1977, Ms. Doris J. Spencer, a black female

GS-13 computer specialist, brought an informal charge of race and

sex discrimination alleging that her employer, MarAd, had dis

criminated against her on the basis of her race and sex by reason

of her non-selection for a competitive position. Complaint (JA

at 1). However, this claim related solely to her individual

discrimination claim and did not raise or imply any claims on

behalf of any class of similarly situated female or black persons.

Ms. Spencer's claim related to her failure to receive a promo

tion. Thereafter, Ms. Spencer's individual claim (later filed as

a formal administrative complaint) was settled at the adminis

trative level. (DX 98, 110 & 132).

On May 17, 1977, Ms. Janis M. Lawrence, a white female GS-12

economist, brought an informal charge of sex discrimination

alleging that her employer, MarAd, had discriminated against her

on the basis of her sex. Within fifteen days of receiving a

notice of final interview with the EEO counselor on July 20,

1977, she filed her formal administrative complaint. Complaint

(JA at 1).

On June 6, 1977, Mr. Dennis L. Harrison, a black male GS-13

engineer, brought an informal charge of race discrimination

alleging that his employer, MarAd, had discriminated against him

on the basis of race. Within fifteen days of receiving a notice

of final interview with the EEO counselor on July 26, 1977, he

filed a formal administrative complaint. Id. (JA at 1).

3

On August 3, 1977, all three named plaintiffs filed a formal

administrative class complaint with the Department of Commerce

and MarAd which was then transmitted to the former Civil Service

Commission ("CSC"). Id. (JA at 13-14).

On March 21, 1978, the CSC, through its Complaints Examiner,

issued a recommended decision to the Department of Commerce on

the issue of accepting the class complaint for processing. On

March 30, 1978, the Department of Commerce issued a final decision

accepting the class complaint for processing. Id. (JA at 14).

On December 29, 1978, the CSC transferred the administrative

class complaint to the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

("EEOC"), which never assigned a Complaints Examiner to the class

complaint. Id. (JA at 14).

On July 11, 1979, the three named plaintiffs filed a civil

action "on their own behalf and [pursuant to Rule 23(b)(2), F.R.

Civ. P.] on behalf of . . . all Black and/or female applicants,

past and/or present employees . . . for discrimination in employ

ment on the basis of race and/ or sex" by defendants. C.A. No.

79-1816. Complaint (JA 1). The case was immediately assigned to

Judge Oberdorfer.

On November 8, 1979, plaintiffs filed a motion for certi

fication of the class. (R. 30, 32). On December 21, 1979, at

the same time they filed their opposition to plaintiffs' class

certification request, defendants moved to dismiss Janis M.

Lawrence as a representative party. (R. 46, 47).

4

On February 13, 1980, Judge Oberdorfer granted plaintiffs'

class certification motion and denied, without prejudice, defend

ants' motion to dismiss Ms. Lawrence as class representative. As

certified under Rule 23(b)(2), F.R. Civ. P., the class included

"all past, present and future Black male, Black female, and white

female employees and applicants for employment at the Headquarters

Office of the United States Maritime Administration. . ." (JA

152).

On August 4, 1980, Judge Oberdorfer issued a detailed pre

trial order setting forth filing deadlines for the parties to

meet before trial. (JA 153). Extensive submissions and amend

ments were then filed by both sides, and after further refining

the issues, the Court issued a revised pretrial order on March 11,

1981. (JA 158).

On April 6, 1981, defendants moved for modification of the

class certification. The basis for this motion was to have the

Court limit membership in the certified class to Blacks and women

working, or applying for work, at MarAd Headquarters before

February 27, 1981, the date established for the closing of

discovery. (R. 292). The Court denied this motion on June 22,

1981. (JA 164).

On October 7, 1981, after several more months of discovery,

defendants moved to dismiss the complaint for failure to exhaust

administrative remedies. The basis for this motion was that (1)

neither plaintiffs Harrison nor Lawrence had ever sought or

5

meaningfully obtained the requisite informal EEO counseling

previously claimed to have taken place; and (2) plaintiff Spencer,

following pursuit of her own individual remedies, had previously

obtained complete relief on her claim and was therefore barred

from proceeding further in the case. In the alternative, defend

ants again requested that the Court modify the class certifica

tion. The basis for this was (1) the class representatives'

close association with the MarAd EEO Committee disqualified their

representative status; (2) according to plaintiffs' statistical

studies prepared for trial, the overly-broad class needed to be

limited to non-supervisory administrative, professional and

technical employees in order to accurately address the discrimi

nation claims; and (3) the "inherent antagonism and conflict"

between blacks and women (competing for the same positions)

created an impermissible conflict within the class. (R. 137).

On October 14, 1981, plaintiffs, while responding to defend

ants' October 7, 1981 motion, moved to strike that same motion.

(R. 144, 145). At a hearing held that same day, Judge Oberdorfer

denied both parties' motions, including the class modification

request. (JA 165).

The trial of this case was then conducted before Judge

Oberdorfer between February 17, 1982 and February 26, 1982. At

the trial's conclusion, the Court directed the parties to file

post-trial briefs, including proposed findings and conclusions.

6

On April 20, 1982, at the same time that the parties were

submitting their post-trial submissions, plaintiffs moved for

leave to file supplemental statistical evidence. On May 4, 1982,

the Court denied that motion. (JA 197).

On June 7, 1982, Judge Oberdorfer issued his findings on

liability. (JA 198). The Court ruled in favor of MarAd on those

portions of the class relating to sex discrimination. However,

the Court ruled in favor of plaintiffs on certain portions of the

class relating to race discrimination ("all black past, present

and future employees"). Because the trial had not addressed the

issue of relief, the parties were directed to file submissions to

assist in formulating relief for the prevailing portion (e.g.,

blacks) of the class. (JA 239).

Thereafter, the parties submitted extensive comments on the

issue of relief. In addition, on August 6, 1982, defendants

moved the Court for amended and additional findings. (R. 215).

On November 19, 1982, defendants filed supplemental information

regarding the application of the 0PM X-118 qualification stand

ards . (R. 229) .

On November 23, 1982, the Court held a hearing on the

post-trial relief proposals and directed the parties to file

further submissions, including any joint statements. Consequent

ly the parties submitted further relief proposals.

On January 14, 1983, the Court held a further hearing on the

relief proposals. Thereafter, on January 25, 1983, Judge

Oberdorfer issued a memorandum and proposed injunction on

7

the relief issues, entering judgment in accordance with the

Court's prior liability findings and directing the parties to

file comments on the proposed injunction. 559 F. Supp. 943

(D.D.C. 1983) (JA 240). On March 18, 1983, Judge Oberdorfer

issued his final injunction. (JA 254). This relief order

provided for wide-ranging injunctive relief including: estab

lishment of an accelerated discrimination complaint process;

revised recruitment, training, awards, promotions and appraisal

procedures; a comprehensive validation plan for all positions at

GS-12 and below; reporting and monitoring requirements; a claims

procedure to allow unnamed, prevailing class members (presumably

applying to all black employees below the GS-13 level), to file

back pay claims; and retention of jurisdiction over the case for

five years.

On March 28, 1983, plaintiffs moved to alter or amend the

March 18, 1983 judgment, (R. 244), requesting the Court either to

eliminate the restrictions on claims to the prevailing class

claims below the GS-13 level, or to provide that prevailing class

members relating to promotions to GS-13 or above levels be

"informed" of their option to pursue such claims on an individual

basis. On April 14, 1983, the Court denied that motion.

(JA 267).

On June 13, 1983, the parties filed cross-appeals from Judge

Oberdorfer's liability, relief and reconsideration rulings regard-

3 /ing the class. —

37 While the appeals have been pending, and pursuant to the

District Court's injunction, MarAd has forwarded to all blacks

employed between July 4, 1977 and March 18, 1983 notices of the

Court's decision and claim forms for requests for individual

relief. See Record in the District Court, C.A. No. 79-1243.

8

Statement of Facts

The factual findings are extensively set forth in Judge

Oberdorfer's opinion dated June 7, 1982 (Op.)(JA 198) and are,

for the most part, uncontested.

The Maritime Administration

I. Background

A. HarAd's Organization

The events which are at issue in this appeal involve the

Maritime Administration, ("MarAd"), a primary operating unit of

the Department of Commerce until August 1981, when it was trans

ferred to the Department of Transportation. More particularly,

the subject events took place at MarAd Headquarters located in

Washington, D.C. — MarAd's mission and function are to foster

the development and maintenance of an American merchant marine

sufficient to meet the needs of the national security and of the

domestic and foreign commerce of the United States.

During the relevant time period, MarAd headquarters has been

organized into a number of independent offices such as Public

Affairs, General Counsel, Civil Rights, etc., as well as into a

57 Until August 1981, MarAd was headed by an Administrator who

also served as Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Maritime

Affairs. While MarAd headquarters is located in Washington,

D.C., there are a number of regional MarAd offices throughout the

nation as well as the United States Merchant Marine Academy. The

certified class represented by the named-plaintiffs are all past,

present or future black and/or female employees of MarAd Head

quarters. Neither the regional offices nor the U.S. Merchant

Marine Academy are involved in this case.

9

number (usually 4) of larger units each of which is headed by an

Assistant Administrator. Op. at 3 (JA 200).

The great majority of employees at MarAd headquarters are

general schedule (GS) employees, with jobs ranging from general

clerical to high level executive positions and including adminis

trative, technical and professional jobs. Professional jobs

include, inter alia, those of engineers, economists, naval archi

tects, attorneys, computer programmers, analysts and statisticians.

Id. MarAd has many different job titles, including a significant

number of jobs that are and unusual in government service because

of its relatively specialized function. (DX 130). These include,

for example, ocean shipping analyst and trade-route examiner.

Id. In addition, there are a number of more standard profes

sional positions, such as engineers, economists, statisticians,

computer programmers and analysts. Op. at 4 (JA 201). The

support staff includes secretaries, clerks, administrators, and

the standard range of positions in any governmental office. Id.

B . MarAd1s Personnel System

1. Background

MarAd's personnel system is similar in structure to those at

other federal agencies. Like other agencies, MarAd operates its

personnel system within the confines of a wide array of published

practices. (DX 129, 130). Supervisors are responsible for

preparing position descriptions for each position under their

supervision. Id. The position description determines the

position title, job series and grade level of a particular job.

10

(Id.). The position description is used in developing vacancy

announcements for open positions and for determining the proper

classification of positions as to job series, position title and

grade level. Id. (DX 106; PX 19).

The MarAd personnel office has authority and direction over

employment practices at MarAd subject, of course, to regulations

and directives from the Office of Personnel Management (0PM),

(pursuant to 5 C.F.R., the Federal Personnel Manual, etc.), the

Department of Transportation (DOT) (and formerly the Department

of Commerce), and the Office of Management and Budget (0MB). Op.

at 6 (JA 203). The personnel office is under the supervision of

the Assistant Administrator for Policy and Administration. Id.

The basic standards for classifying positions and for de

termining the minimum qualifications for general schedule employees

are found in the Classification Standards and in Handbook X-118

issued by 0PM. See F.P.M. Ch. 315 § 1-4 (1981); F.P.M. Ch. 335

§ 1-4, 5a; F.P.M. Ch. 338 § 3-1, et se£.; and DX 2 (the X-118).

2. Procedures for Competitive Promotions

There are essentially two types of promotion at MarAd,

competitive and non-competitive. Op. at 6 (JA 203; DX 129). To

initiate a competitive promotion, the supervisor requests that a

vacant position be filled by forwarding to the personnel office a

position description on SF-52 for the vacant position. (DX 104).

A personnel staffing specialist then writes a vacancy announce

ment by referring to the position description and the X-118

11

minimum qualifications. (PX 19). Other minimum qualifications

may also be listed in the vacancy announcement, Op. at 7 (JA

204), however MarAd only added such qualifications once during

the time in question. (DX 129).

At MarAd there are a number of unusual jobs that relate to

the subsidy functions but, nevertheless, are classified according

to standards issued by 0PM. (DX 130; PX 171 and 140). In such

cases the classification division looks to similar classification

standards and constructs an applicable standard for the job. (DX

130).

Each vacancy announcement is then posted and distributed to

a number of public and private agencies and interest groups.

Since December 1979 all persons who wish to be considered for a

vacancy must describe their qualifications on Standard Form 171.

(Before December 1979 MarAd employees had the option of being

considered based on their official personnel folders). All

application forms are reviewed by the assigned personnel staffing

specialist to determine whether the applicant meets the basic

qualifications for the position. Id.

All those applicants who are determined to be minimally

qualified are then designated as "eligible." There is no limit

on the number who may be designated as "eligible." (DX 104).

All persons who do not meet the minimum qualifications for the

position are designated as "not qualified" and are so informed.

Op. at 7 (JA 204) (PX 171). See 5 C.F.R. §300.101 et seq. ;

§338.101; and the X-118 standards. (DX 2).

12

The personnel staffing specialist's job of determining an

applicant's eligibility involves the application of both objec

tive and subjective criteria. The determination involves some

judgment and discretion as to whether the applicant's qualifi

cations are comparable or equal to the basic qualifications. (DX

129). For example, one of the professional positions at MarAd is

that of Budget Analyst, in the GS-560 Series. The minimum

qualifications for the position include some requirements that

are general and open-ended: the applicant must have gained a

"general knowledge of financial and management principles and

practices applicable to organizations", including "specific

knowledge and skill in the application of budgetary principles,

practices, methods and procedures directly related to the work of

the position to be filled." (_Id; DX 2). The matching of what is

on an applicant's SF-171 with these types of general requirements

consequently involves the use of objective standards (e.g., years

of specialized training, experience, etc.) and judgmental ele

ments (the personnel specialist's determination of whether the

individual's qualifications are compatible with the requirements

of the standard).

Once the personnel staffing specialist has determined

whether an applicant is eligible, the next step is the rating and

ranking of the eligibles, either by a panel or the personnel

staffing specialist. Prior to December 1979, promotion panels

evaluated. candidates who met the basic qualifications for all

supervisory positions and for all positions at the GS-13 level

13

and above. Op. at 8 (JA 205). Since December 1979, promotion

panels have been used less frequently, e.g. , only to evaluate

candidates when there are more than 10 candidates for a position

at GS-13 and above. (DX 104; DX 129). If there is not a promo

tion panel for the particular vacancy, the personnel staffing

specialist reviews all candidates who meet the basic qualifi

cations for the purpose of ranking the applicants. Id.

Prior to December 1979, the rating and ranking were based on

four factors: (1) experience; (2) education and training; and

(3) to a lesser extent awards and supervisory appraisals. Id.

Prior to December 1979, the appraisal of a performance of a

candidate was obtained by asking the candidate's most recent

supervisor or employer to complete either form MA-68 or MA-105

depending on whether or not the candidate was a MarAd employee.

Id. For supervisory positions, candidates were also evaluated

and ranked on the basis of managerial skills and leadership

qualities. Id. Since December, 1979, ranking and rating has

been done on the basis of education, training and experience.

Op. at 9 (JA 206). Supervisory appraisals and awards are con

sidered by the selecting officials after the rating and ranking

has been done. Id.

Weights are then assigned to each of the criteria, points

given to each candidate for each criteria, and results combined

to determine a final ranking of qualified or highly qualified

applicants. Id. Based on a fixed point score (usually 80

14

points), candidates were deemed to be highly qualified or quali

fied. (PX 171). The personnel staffing specialist then prepared

a Merit Promotion Certificate listing the names of those found

highly qualified alphabetically, and then those qualified also

alphabetically.

The scores given to the candidates were not placed on the

certificate given to the selecting official. Op. at 9 (JA 206)

The selecting official could select any of the persons listed on

the certificate. However, prior to June 1979, the selecting

official was required to state his or her reasons for selection

on the certificate. Id.

3. Competitive Promotions

After December 1979

Since December 1979, all persons meeting the basic minimum

qualifications have been rated and ranked to determine whether

they should be found to be "best qualified" or "qualified". Op.

at 10 (JA 207). If less than ten persons have been found to be

qualified for a vacancy, the names of all the qualified appli

cants are sent to the selecting officials along with the 171

forms without their being rated or ranked. (DX 105).

Since December 1979, the selecting official has been given the

option of having the personnel office obtain written performance

appraisals or to obtain them orally by contacting the candidate's

reference(s). Op. at 10 (JA 207) (PX 171). In the majority of

cases selecting officials have chosen to obtain the performance

evaluation themselves through oral communications with the

15

references provided by applicants. (PX 171). There is no record

maintained by the personnel office as to the contents, format, or

results of oral requests for performance evaluations. Op. at 10

(JA 207).

4. Validation of Selection Procedures

There have been no formal validation studies conducted by

MarAd with regard to the selection process overall, including the

standards used to rate and rank candidates, the cutoff scores

used to determine whether a person is highly qualified, best

qualified or qualified, or the use of awards and appraisals. Op.

at 10-11 (JA 207-08) (PX 171).

In October 1980, pursuant to a directive of the Department

of Commerce issued in January 1980, MarAd began the process of

collecting applicant flow data by asking applicants voluntarily

to fill out forms indicating their race. Op. at 11 (JA 208).

Prior to that time no applicant flow data showing the race of

applicants were sought, collected or maintained. Id.

5. Non-Competitive Promotions

In addition to competitive promotions, employees may also be

promoted non-competitively. There are two main types of non

competitive promotions: (1) promotions along a career-ladder,

and (2) promotions resulting from the accretion of duties leading

to a reclassification to a higher grade level. Id.

a. Career-Ladder

The first type of non-competitive promotion is a promotion

in a career-ladder series. Slightly over one-half of the middle

level (Grades 7-12) employees are within career-ladder positions.

16

MarAd has the authority to designate any series a career-ladder

series. — ̂ The final authority for approving the designation of

job series as career-ladder series lies with the Assistant

Secretary for Maritime Affairs. Op. at 12 (JA 209).

It is necessary to compete for entry into a career-ladder

series, which may be entered at the lowest level or at a GS level

within the ladder. Id. Once accepted into a career-ladder

series, an employee may be promoted without competition until

reaching the journeyman, or top designated, level. Id. In order

to advance beyond the journeyman level, an employee must either

compete for a higher grade position for entry into another

career-ladder, or acquire a promotion through accretion of

duties. Id.

37 This authority is found in FPM Chapter 335-5, § 1-5 which

states:

"c. Agencies may at their discretion except

other actions from their [competitive

promotion] plans. These include, but

are not limited to:

(1) Two types of career promotions:

(a) A promotion without current

competition when at an earlier stage an

employee was selected from a civil

service register or under competitive

promotion procedures for an assignment

intended to prepare the employee for the

position being filled (the intent must

be made a matter of record and career

ladders must be documented in the

promotion plan); or

(b) [by an accretion of duties

promotion]. [DX 106].

MarAd established this procedure in MAO 730-335.

17

A promotion along a career-ladder series typically depends

on the supervisor's requesting a promotion by submission of a

Standard Form 52 attesting that the employee is performing duties

at the higher grade level, once the "year-in-grade" eligibility

requirements of 5 C.F.R. § 300.601 et seq., have been met. Id.

at 13 (JA 210). Supervisory appraisals are not obtained by the

Office of Personnel when a career-ladder promotion is

recommended. Id.

(b) Accretion-Of-Duties

The second type of non-competitive promotion at MarAd is an

accretion-of-duties promotion. This promotion results from an

employee's position being classified at a higher grade because of

additional duties and responsibilities.

Prior to December 1979, a promotion by accretion of duties,

under the applicable regulations, was to be given only when the

increase in duties was unplanned. Id; (PX 178; DX 129). If it

was planned to enhance the duties of a position so as to permit

it to be classified to a higher level, then the position had to

be open to competition; otherwise a promotion by accretion of

duties was non-competitive. (Id.)

A supervisor may initiate an accretion-of-duties promotion

by sending a standard form to the personnel office requesting

that an employee be promoted without competition because his/her

duties have increased in level of responsibilities or difficulty

so as to justify classification at a higher grade level. An

employee can obtain a position audit if he or she believes the

18

job has changed. It is the task of the personnel office to

determine whether the new duties justify the higher grade level.

Op. at 14 (JA 211).

An employee may be transferred from one job to another by a

lateral transfer at the same GS level unless the new position has

potential for promotion. _Id. In such a case, it is necessary to

compete for the lateral transfer. Id; (PX 16).

6. Training

The division of Employment and Training has jurisdiction

over training at MarAd. With the exception of a few programs,

funds for training are provided for courses and training sessions

related to the functions of the job already held as described in

the position description. Op. at 14 (JA 211); (DX 131; PX 141).

Each office and division at MarAd is assigned an established

amount as a training budget and an Individual Development Plan is

prepared for each employee along with his or her supervisor each

year. An employee must request training from his/her supervisor,

who has discretion to deny it. Id.

While there is no right of direct review by the personnel

office if the supervisor denies the training, employees may go to

a higher level supervisor. If training is still denied, the

employee's recourse is to file either a grievance or other

administrative complaint. Id. at 15 (JA 212); (DX 131).

7. Awards

The awards process begins with a nomination by a supervisor.

While an employee who believes he or she is entitled to an award

19

has no right directly to appeal to the personnel office or to an

awards committee, he or she can go to a higher level supervisor.

Op. at 15-16 (JA 212-13).

Prior to 1978, there was an overall awards committee that

reviewed nominations for awards and was representative of the

MarAd workforce. The system was revised, however, so that each

department has an awards committee consisting of each major

organizational unit, with the deputy assistant administrator as

chairperson. Id; (DX 104 & 105; PX 20). The award committees

have the power to approve money awards, except that quality step

increases (which result in an indefinite increase in pay) must

also be approved by the personnel officer. Id. In addition to

monetary awards, there is a medal awards committee, consisting of

the Assistant Administrators, which can approve nominations for

Bronze Medals and can pass on to the Department of Commerce (now

the Department of Transportation) Gold and Silver Medal nomina

tions. Id.

8. D isciplinary Actions

With regard to disciplinary actions (which are rare) the

supervisors have the discretion and power to initiate such

actions, including letters of reprimand, warnings, proposed

suspensions, or more serious proposals for adverse action. Op.

at 16 (JA 213). The personnel office consults and advises with

supervisors through its Division of Labor and Employee Relations

regarding discipline. Id.

20

9. Reorganization

Also under the jurisdiction of the Assistant Administrator

for Policy and Administration is the Office of Management and

Organization. This office is responsible for studying proposals

for reorganization, developing management studies and forwarding

its recommendations to the Assistant Administrator for Maritime

Affairs for final approval. Id.

II. The Anecdotal Evidence

While both plaintiffs and defendants introduced anecdotal

evidence at trial, the District Court concluded that such evidence

"offers little help to either side." Op. at 25 (JA 225).

Plaintiffs presented the testimony of several individuals

who believed they had been the victims of discrimination at

MarAd. (Tr. 267-550). The Court determined that, while the

testimony left "room for doubt as to the correctness and non-

discriminatory nature of individual [personnel] decisions," this

evidence

was not sufficient...to reach conclusions on

the question of whether individual class

members who did not receive promotions or who

received promotions after longer periods of

time than usual were qualified for the

promotions which they claim they were denied

discriminatorily.

Op. at 25 and 26. (JA 225-26).

MarAd submitted affidavits of blacks and females who reported

neither to have experienced nor observed discrimination and also

called numerous witnesses to rebut the claims of discriminatory

treatment made by individual class members. (Tr. 551-820,

21

882-896). However, even though the Court determined that the

anecdotal evidence did not lead it to suspect discrimination

where the statistical evidence (infra) indicated its absence, it

was not "reassure[d]" by this finding where certain statistics

showed what it considered to be "substantial adverse impact of

MarAd selection procedures." Op. at 26 (JA 226). Consequently,

the Court placed "primary reliance" on statistical evidence, even

though the individual class members' testimony failed to support

their claims of discrimination.

III. The Statistical Evidence

As noted above, the District Court placed "primary reliance"

on statistical evidence in making its findings. This evidence

addressed the claims of sex and race discrimination. As noted,

the District Court ruled that MarAd had not discriminated on the

basis of sex. However, in reviewing this evidence and ruling

against MarAd on the issue of race discrimination, Judge Oberdorfer

rej ected the statistical evidence proffered by the complaining

class and embraced those statistics introduced by MarAd. As a

result, the trial judge concededly based his race (and sex) dis

crimination finding on evidence which clearly shows that no

members of the class are entitled to relief -- defendants'

statistical proof demonstrated that the class members were not

under-represented or under-selected for hiring or promotion at a

significant statistical rate. Consequently, the District Court's

finding that MarAd discriminated against black employees is

contradicted by the very record upon which it placed "primary

reliance."

22

A. Statistical Overview

As a general matter, it is undisputed that white males

comprise a large majority of those persons employed at high GS

levels and Senior Executive Service (SES) levels. However, as

the District Court seemed to recognize in its analysis (but not

in its final ruling) the legal significance of the statistics

which examine the race of personnel at MarAd can only lead to the

conclusion that any differentials between whites and blacks in

hiring or promotion at MarAd are statistically indistinguishable.

B. Statistical Evidence Presented

by the Class__________________

Plaintiffs' statistical evidence was largely derived from

MarAd's computerized Employee Information System (EIS), which was

furnished to plaintiffs during discovery. This system was

implemented in 1976, and includes employment histories dating

back to the early 1970's for employees who were at MarAd when the

program was instituted. It does not include data on employees

who left MarAd prior to 1976. From the data on the EIS tape an

employee of plaintiffs' counsel prepared a number of tables. (PX

F7 The analytical studies of the compiled data were done by

Professor John Van Ryzin of Columbia University, a professor in

the Department of Biostatistics and Mathematical statistics. His

work was done in connection with the consulting firm Statistica,

of which Dr. Van Ryzin is a member. Though Dr. Van Ryzin himself

had not previously testified as an expert in an employment discri

mination case, he had consulted with other members of Statistica

who have. Defendants stipulated to his qualifications and the

Court found that he was qualified to testify as an expert. Op.

at 17 (JA 214).

23

The class members' statistical evidence focused solely_on

the "white-maleness" of those persons employed in higher-ranking

positions at MarAd headquarters. This analytical approach

underscored the compound "race/sex" discrimination theory plain

tiffs raised throughout the case. Indeed, the statistical

configurations proffered by the class repeatedly emphasized their

notion of a "white-maleness" propensity in hiring and promotion. —

The class also relied heavily on statistics showing different

promotion rates for white males as opposed to other race-sex

combinations. (PX 1). This evidence focused on the middle-level

positions (GS-7 thru GS-12), for which the statistics show

significantly different promotion rates between the various

groups. In addition, the class members' expert also performed

an analysis of the frequency of promotion by race and sex. (PX

4). While this study showed statistically significant differences

7 7--For example in 1981), 78% of white males were employed at

above GS-12, while only 17% of white females, 26% of black males

and 4% of black females were so employed. The Court noted that

such a pattern could be observed if MarAd had previously_ engaged

discrimination but was free from discrimination during the

time periods relevant to the suit. Op. at 17 (JA 214). In

addition, it noted that this pattern could well be due to a

difference in education and training necessary for the jobs m

question and not due to discrimination. Id.

8 / For example, the mean time to promotion of white males at the

GS-7 level is 434 days, as opposed to 1,015 for white females,

1,278 for black males, and 1,888 for black females.^ Op. at 18

(JA 215). The disparities at GS-9, 11, and 12, while nop so

severe, were observed by the District Court to follow a similar

pattern. Id.

24

in promotion ra tes between the four groups at the GS-7. 9 , 11 and

12 levels the Court found that there were small, In sign ifican t

differences at the GS-13 and 14 lev els . <K 4, Op. at 18) <JA 215)

The class members' expert also performed several regression

analyses. i ' These analyses attempted to assess the e ffe c t of

ra te and sex on salary while also accounting for the e ffe c ts of

years of service and educational lev el. <PX 4 ) . Later analyses

included variables for specialized training and for years between

school and MarAd employment, although the type or sp ecialty of

train in g was never accounted fo r. (PI 179). However, there was

no accounting for the minimum ob jectiveq u alification s necessary

to be e lig ib le for the various and diverse positions a t MarAd.

,. , j _ ffprence a fte r accounting for theAll the studies showed a d itterence

above facto rs between the sa laries of whites and blacks and males

and fem ales, and a more substantial and sign ifican t difference

between the sa la rie s of white males and a l l others. Id .i Op. at

19 (JA 216). The class members asserted that these differen

indicated the presence of a "white-maleness" e ffe c t on salary ,

separate and d is tin ct from the e ffe c t of being white and the

-t----- cT 7- f suup 873 (D.D.C. 1981) affjd in £artI I Trout v. Lehman, u F. |*PPj cir. 1983) , cert. E£t.

and m e r ^ i n ^ r t . 3387 (No. 83-706), (Trout) andA$ ^ - ^ s pending, 52 U.b.n.w. \ n iq«d appeal pending, Nos.

CiviTetti, 508 F.Supp. 690 (D(* ? ± r) 8 m u ^ T T rfeiiiion is a

82-1541 and 1590 (D.'c* . : ) r„Ultimate the effects of severalstatistical device design . dependent variable. See

Proceedings, 80 Col.L.Rev.

702, 721-25 (19»U).

25

effect of being male. In the first, more sophisticated regres

sion analysis, the Court noted that neither race nor sex alone

were shown to have a statistically significant effect on salary,

but the "white-maleness" effect was significant. (Op. at 19) (JA

216). If however, the "white-maleness" term was removed from the

regression analysis both race and sex were noted as having

significant effects on salary in most years. (Id.)

C. MarAd's Response

MarAd asserted that the class members' regression analysis

was faulty because it failed focus on the conduct that was

legally at issue -- specific decisions of MarAd in hiring and

promoting employees, especially given the diverse eligibility

requirements of many of its positions. Rather, the regression

analysis focused on the distribution of jobs within MarAd without

separating decisions made by MarAd within the relevant time frame

from decisions made prior to that time or from decisions made by

employees themselves.

MarAd argued that a more appropriate analysis was to look at

actual MarAd decisions and examine those for evidence of discrima-

tion. Plaintiffs' study of time to promotion and rates of pro

motion were directly relevant on these issues. Op. at 19 (JA

216). However, the primary problem with these studies, according

to MarAd, was that they combine two very different promotion

paths into one analysis. (See discussion below). This is

because slightly over one-half of the middle level (Grades 7-12)

26

employees at MarAd are professionals in career-ladders and thus

received the bulk of their promotions non-competitively and at

relatively regular intervals. Though promotions in career-ladder

positions are not automatic, they are much more frequent than m

non-career-ladder positions, where the vast majority of all

promotions are obtained by competing with applicants from both

within and without MarAd, and are predominantly clerical and

non-professional. Op. at 19 (JA 216). Consequently, MarAd

rebutted the class members' statistical analysis by offering two

separate analyses of promotions -- one focusing on competitive

promotions and another on non-competitive promotions.

1 . Non-Competitive Promotions

MarAd's study of noncompetitive promotions consisted of a

survival analysis in many ways similar to that conducted by the

class members, (which, as noted, examined the time to promotion

at various grade levels). (DX 119). This analysis (of

"tenure" in grade) showed no significant statistical differences

at GS-7, 9, or 11 in career-ladders. Another analysis of all

professional positions at those levels arrived at a similar

conclusion. However, when all grades were aggregated - risking

over-aggregation of vastly dissimilar positions — there was a

T7T7— MarAd1 s analysis o'F"noncompetitive promotions was performed hf Dr timothy Wyant, Senior Statistician at Econometric Research,

Inc ("ERI") Dr. Wyant, who holds a Ph.D in biostatistics from

S h A s (Hop£iis University and is experienced in the use of statis

tics in the employment context, was found bv the Court to be

"eminently qualified" as an expert in the field. Op. at ZU

(JA 217).

27

disparity between the promotion rates of blacks and whites as

well as between white males and all others. Id. The Court noted

that these two disparities would occur by chance .07 and .06

times, and that such a probability, (while above the .05 thres

hold normally associated with statistical significance), repre

sented an "unlikely result" with a race-blind advancement process.

Op. at 20 (JA 217). In addition, the Court observed that these

probabilities were based on a "two-tailed test rather than a

"one-tailed" test. — ̂ If a one-tailed test had been used, the

relevant probabilities would be roughly one-half the aforemen

tioned magnitudes and therefor significant at roughly the .05

level. — (DX 119; Op. at 20; JA 217).

According to the Court, this study did not purport to

"explain" why white males are represented more frequently in

career-ladder positions than in noncareer-ladder positions. Op.

at 21 (JA 221). However, the Court also noted that these posi

tions "are all professional and the differences may be due in

part to differences in educational and similar qualifications.

Id. However, as the Court also noted, (Id.) to the extent that

XT7 A two-tailed test basically estimates the likelihood of a

statistical difference of a given magnitude in either direction,

while a one-tailed test gives the likelihood of a statistical

difference in the direction observed. Op. at 20 (JA 217)

(DX 119). It should be noted that the Fourth Circuit has

severely critized the use of one-tailed tests, categorzing them

as result-oriented. See EEOC v. Federal Reserve Bank of

Richmond, 698 F.2d 633, 655-56 (4th Cir.1983).

12/ In addition, this analysis found only a small, statistically

Insignificant difference between the promotion rates of white

males and white females. (DX 119; Op. at 20; JA 217).

28

employees were hired into MarAd after January 1, 1977, their

placement in career-ladder positions was addressed and explained

by the following competitive analysis.

2. Competitive Promotions

MarAd's analysis of competitive promotions examined the

filling of vacancies by competitive announcements from January 1,

1977 to March 26, 1981. <DX 120). This necessitated going

beyond the EXS tape, since the data on the applicants for these

positions was not contained there. Id. The necessary informa

tion was obtained from MarAd applicant files which date back to

1974 or 1975 and are complete beginning in 1976. Id. This

information was incomplete, however, to the extent that it did

not contain data on the race of most of the applicants who were

not employed by MarAd either before or after applying. —

The competitive promotion analysis examined each vacancy

announcement and the results from filling it, and then aggregated

the resulting data to obtain a total probability for various

groups of the observed results assuming a sex and race neutral

selection process. (DX120) . This aggregation was done by using

13/ MarAd1 s ana iysis oi comPe^ J ^ i n t Ind'f^ior^artner0 at

^ e n f l y ^ n ,ualified

as an expert in the field. Op. at 21 (JA i l l ) .

14/ Some of h l T w o ^ e d ^ t

f^ rT h e ^ f^ e ra i g -rn m e n t Howeve^, ™ « «

available only beginning in . ^ e r 19a ’ L Op. at 21 (JA 221);

tin ely returned to the applicant the agency, up.

(DX 120).

29

the "Multiple Pools Exact Test," which has the virtue of allowing

for the composition of individual applicant pools while still

yielding meaningful overall statistics. Id- the Court noted,

such tests are particularly well suited for situations where, as.

here, applicants compete against each other rather than against a

fixed standard and the racial composition of the pools varies

from job to job. Op. at 22 (JA 222). This analysis also compared

the aggregate selection rates by race and sex in the various

grades. (DX 120).

The data with respect to race was found by the Court to be

more "problematical" than that pertaining to sex (which, as

noted, clearly undercut any implication of sex discrimination).

Op. at 23 (JA 223). This was apparently caused by an under

selection of blacks at GS-12 and below (measured at .04) from

among all anolicants and very random selection at GS-13 and above

(measured at approximately .50). The underselection at GS-12 and

below was attributable to low selection rates of blacks in

15/ *he results ol g ^ H z ! ) hheTggre-lfff

S l S aionSiatePofafemalJs was fiund to be more thf twice that of

males. Id. Applying the multiple pool tests, ^ p r o ^ . ^

such a number or females or few females was shown,

a statistically significant overse stent with the hypothesisId. This is, of course completely inconsistent women in

tKat MarAd discriminated on t h e w i t h respect to race did not these selections. The missing data with respect to^ applicants

effect this analysis, attacked this conclusion by arguingwas known. The class memoerb f pmt,iovees from withinthat it was due to a bias in favor of the total

HarAd, a group that tended allowing for such an effect,

f emale^continued ̂ 'o^b'e^verselected^ not under selected^ although

beinconsistent with a hypothesis of sex discrimination. Id.

30

clerical positions. However, this disparity disappeared at the

eligibles stage (where it rose to .22). (DX 120).

As indicated above, there was missing data on the race of

applicants, the overwhelming bulk of the missing data being that

of rejected applicants who never actually worked at the agency.

In MarAd's original analysis this essentially meant that most of

the pools, which consisted of only one racial group if unknowns

were excluded, did not influence the results, and the probabili

ties were thus based on only around one-fourth of the applicant

pools. (DX 120). While many of these pools may have only one

racial group, given the number of applicants for whom data was

missing, the Court found that the exclusion of this many pools

substantially lessened the probative weight of MarAd's race

analysis. Op. at 23 (JA 223).

MarAd then did an additional analysis in which it assumed

that the race-unknown applicants had a racial composition similar

to that of the known-race applicants for similar positions. (DX

120). This analysis resulted in data more favorable for MarAd,

so the agency relied primarily on the former analysis in order to

give plaintiffs the benefit of the doubt. Id. According to the

Court, the results showed a statistically improbable underselec

tion of blacks

...particularly at the clerical level, but at

other levels as well: There is a selection

rate of blacks from applicants at the clerical

level that would occur by chance only . 0 1 of

the time, and the selection rate from appli

cants for other grades below 13 would occur

only .04 of the time.

(Op. at 23) (JA 223). MarAd pointed out that this result improves

if the race-unknown persons were assigned races on the basis of

31

the composition of the race-unknown applicants. (DX 120);

However, the Court inexplicably concluded that the disparity

continues to "favor whites," not specifying the degree to which

such disparity was significant. Op. at 23 (JA 223).

D. The Class Members' Response to

MarAd's Statistics____________

The class members responded in several ways to the analyses

of MarAd's experts. First, they argued that it was improper to

examine race and sex separately, because of the danger of combin

ing white females with white males in the race analysis and black

males with white males in the sex analysis. (Tr. 993-1043).

Instead, their preferred analysis was to compare white males with

all others at each stage. (PX 179). Such a comparison, they

argued, shewed "statistically significant favorable treatment for

white males" in the selection process. ( Ih.) Second, the

parties disputed vigorously the propriety of defendant's treat-

1 6 /ment of applicants of unknown race. Op. at 24 (JA 224). — 7

16/ For example, the class members' expert performed an analysis

in which he included females of unknown race in the non-white/male

category because these persons were known not to be white males re

gardless of their race. (PX 179). However, the Court held

that MarAd

...correctly responded that to include these

persons in the analysis would heavily bias

the results in plaintiff's favor, since

persons of unknown race were overwhelmingly

those who were rejected. Since a large

portion of the rejected males may well have

been white, including the race-unknown

females would obviously skew the results in

plaintiffs' favor unnecessarily.

Op. at 24’ (JA 224).

32

Thus, additional analyses were done by both sides in which

the race-unknown males were allocated in proportion to their

numbers in the race-known group and, at the suggestion of the

Court, in proportion to their numbers among the rejected race-

known group. Op. at 24 (JA 224). Even with these modifications,

the results of MarAd's analysis remained unchanged. However,

this analysis did not separate out analyses for race and sex to

"enable the court to determine whether this difference is due

entirely to race discrimination, entirely to sex discrimination,

to both, or to the 'compound discrimination' which plaintiffs are

urging here." Op. at 24 (JA 224).

The class members also attacked MarAd's analyses generally

because they alleged that by subdividing the data, smaller groups

are subjected to analysis, and accordingly, a larger difference

had to be observed for statistically significant results to be

obtained. — ^

Finally, with respect to medals and other awards, the class

members maintained that the data showed that white males had

received a disproportionate share of the awards given. Again,

the class did not proffer a separate analysis by race or sex.

17/ The Court noted that this argument was "well taken and

important; obviously if the results in several subgroups all tend

to lie in one direction, a court may find discrimination even

though no single result is statistically significant." However,

the Court then noted in passing that the .05 threshold frequently

used as a test of statistical significance was not an all-or-

nothing measure: "In the context of other evidence levels well

above .05 may be probative of discrimination." Op. at 24 and 25

(JA 224-225).

33

The data that was proffered was found to be generally consistent

with the previous data. (PX 155); Op. at 25 (JA 225) . ) Indeed,

while MarAd's expert stated that the awarding of bronze medals is

non-random with respect to race and sex combined, he denied that

there was any disproportion with respect to cash awards. (DX

120) .

IV. The District Court's Findings and

Conclusions______________________

A. The "Compound" Class Discrimination Claim

In reviewing the massive and complex statistical evidence

before it, the District Court rejected the class members' allega

tions of "compound" discrimination -- the "white-maleness" of the

agency's hiring and promotional system was simply not found to

have any discriminatory basis. Consequently, the underlying

rationale for certifying the broad class of all blacks and women

(e.g., an illegal preference for white-males) was ultimately

disproved. Indeed, the Court concluded that

[h]aving examined and taken into account the

statistics presented by both parties, ...

with a few exceptions those presented by

[MarAd] are more reliable.

Op. at 28 (JA 228).

More particularly, the Court agreed with MarAd that the

class members' attempt to lump together the statistics from

career-ladder and non-career-ladder positions was "irrational",

and that the two had to be examined separately:

It is clear from the record that career-

ladders are designed to and in practice

result in much faster rates of promotion than

34

noncareer-ladder positions. Under these

circumstances, it would be irrational to

assume equal promotability between incumbents

of these two types of positions, as [the

class members'] proposed analysis would

imply.

Op. at 29 (JA 229). Moreover, even though the selection of

positions to be designated career-ladder was within the dis

cretion of the agency, the Court found that MarAd had

...adequately demonstrated that the designa

tion of certain positions as career-ladder is

based on characteristics of the jobs and not

of the persons who occupy them. The career-

ladder positions are professional positions

which are properly graded at two-level

intervals and for which MarAd has an amount

and level of work such that all who enter

could be promoted and work at the full

performance levels. Most professional jobs

at MarAd are career-ladder, and those that

are not are not either because there is no

presumptive full performance level which most

employees would eventually achieve and at

which work would be available, or because the

job is not "truly professional" in the

classic sense, or because the job is one of a

kind or otherwise not suited for stepped

promotion treatment. [citation omitted]

While nonprofessional jobs at MarAd could

possibly be designated career-ladder, there

is no evidence that failure to do so is any

way discriminatory. There is no requirement

that MarAd refrain from providing rapid

advancements to a class of employees whose

positions warrant it simply because that