Plaintiffs' Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law; Order and Preliminary Injunction

Public Court Documents

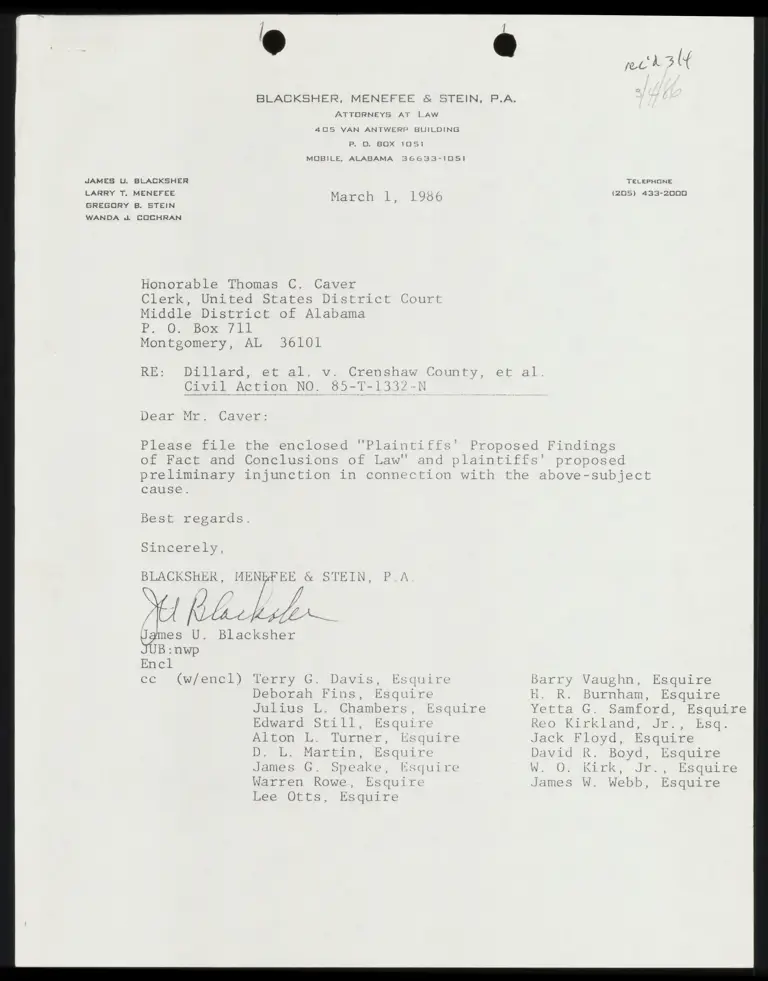

March 1, 1986

72 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Dillard v. Crenshaw County Hardbacks. Plaintiffs' Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law; Order and Preliminary Injunction, 1986. 1e39b1b3-b7d8-ef11-a730-7c1e527e6da9. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/582f9a15-e6c1-4277-9a7b-6ed680515838/plaintiffs-proposed-findings-of-fact-and-conclusions-of-law-order-and-preliminary-injunction. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

|

®

BLACKSHER, MENEFEE & STEIN, P.A.

ATTORNEYS AT LAW

405 VAN ANTWERP BUILDING

P. D. BOX 1051

MOBILE, ALABAMA 36633-1051

JAMES U. BLACKSHER

LARRY T. MENEFEE March 1 | 98 6

GREGORY B. STEIN ™ "3 :

WANDA J. COCHRAN

Honorable Thomas C. Caver

Clerk, United States District Court

Middle District of Alabama

P. 0. Box 711

Montgomery, AL 36101

RE: Dillard, et al. v. Crenshaw County,

Civil Action NO. 85-T-1332-N

Dear Mr. Caver:

Please file the enclosed "Plaintiffs’ Pro

of Fact and Conclusions of Law" and plain

preliminary injunction in connection with

cause.

Sincerely,

BLACKSHER, MENLF EE & STEIN. P.A

7 7) [7 / / T

_¥ / /d

f : bog

Bones U. Blacksher

JB :nwp

Encl

cc (w/encl) Terry G. Davis, Esquire

Deborah Fins, Esquire

Julius L. Chambers, Esquire

Edward Still, Esquire

Alton L. Turner, Esquire

D. "1. Martin, Esquire

James G. Speake, Esquire

Warren Rowe,

lee Otts,

Esquire

Esquire

posed Finding

TELEPHONE

(205) 433-2000

é

tiffs' proposed

the above-subject

Barry Vaughn, Esquire

H. R. Burnham, Esquire

Yetta G. Samford, Esquire

Reo Kirkland, Jr., ILsq.

Jack Floyd, Esquire

David R. Boyd, Esquire

W. 0. Kirk, Jr., Esquire

James W. Webb, Esquire

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE

MIDDLE DISTRICT OF ALABMA

NORTHERN DIVISION

JOHN DILLARD and HAVARD RICHBURG

of Crenshaw County; NATHAN CARTER,

SPENCER THOMAS and WAYNE ROWE

of Etowah County; HOOVER WHITE,

MOSES JONES, Jr., and ARTHUR TURNER

of Lawrence County; DAMASCUS

CRITTENDEN, Jr., RUBIN McKINNON, and

WILLIAM S. ROGERS of Coffee County;

EARWEN FERRELL, RALPH BRADFORD and

CLARENCE J. JAIRRELS OF Calhoun

County; ULLYSSES MCBRIDE, JOHN T.

WHITE, WILLIE McGLASKER, WILLIAM

AMERICA and WOODROW McCORVEY of

Escambia County; LOUIS HALL, dJr.,

ERNEST EASLEY, and BYRD THOMAS, of

of Talladega County; MAGGIE BOZEMAN,

JULIA WILDER, BERNARD JACKSON and

WILLIE DAVIS of Pickens County;

LINDBURGH JACKSON, CAROLYN BRYANT,

and GEORGE BANDY, of Lee County, on

behalf of themselves and other

similarly situated persons,

Plaintiffs,

VS.

CRENSHAW COUNTY, ALABAMA, gua COUNTY;

IRA THOMPSON HARBIN, JERRY L.

REGISTER, AMOS MCGOUGH, EMMETT L.

SPEED, and BILL COLQUETT, in their

official capacities as members of

the Crenshaw County Commission; IRA

THOMPSON HARBIN, in his official

capacity as Probate Judge; ANN TATE,

in her official capacity as Circuit

Clerk; FRANCES A. SMITH, in his

H

HN

WN

WH

WN

WH

AH

WK

HK

FH

KN

HN

WK

WK

RN

HK

HK

WH

RN

NN

KX

%

FH

FH

HF

HK

HX

KX

¥

FX

*

CA NO. 85-7-1332-N

official capacity as Sheriff of

Crenshaw County; ETOWAH COUNTY,

ALABAMA, qua COUNTY; LEE

WOFFORD, in his official capacity as

Probate Judge; BILLY YATES, in his

official capacity as Circuit Clerk;

ROY MCDOWELL, in his official

capacity as Sheriff of Etowah County;

LAWRENCE COUNTY, ALABAMA, gua

COUNTY; RICHARD I. PROCTOR, in his

official capacity as Probate Judge;

LARRY SMITH, in his official capcity

as Circuit Clerk; DAN LIGON, in his

official capacity as Sheriff of

Lawrence County; COFFEE COUNTY

ALABAMA, qua COUNTY; MARION

BRUNSON, in his official capacity as

Probate Judge; JIM ELLIS, in his

official capacity as Circuit Clerk;

BRICE R. PAUL, in his official capa-

clty as Sheriff of Coffee County;

CALHOUN COUNTY, ALABAMA, qua

COUNTY, ARTHUR C. MURRAY, in his

official capacity as Probate Judge;

R. FORREST DOBBINS, in his official

capacity as Circuit Clerk; ROY C.

SNEAD, Jr., in his official capacity

as Sheriff of Calhoun County;

ESCAMBIA COUNTY, ALABAMA, qua

COUNTY; MARTHA KIRKLAND, in her

official capacity as Probate Judge;

JAMES D. TAYLOR, in his officlal

capacity as Circuit Clerk; TIMOTHY

A. HAVSEY, in his official capacity

as Sheriff of Escambia County;

TALLADEGA COUNTY, ALABAMA, dua

COUNTY; DERRELL HANN, in his official

capacity as Probate Judge; SAM GRICE,

in his official capacity as Circuit

Clerk; JERRY STUDDARD, in his

official capacity as Sherlff of

Talladega County; PICKENS COUNTY,

ALABAMA, qua COUNTY; WILLIAM H.

LANG, Jr., in his official capacity

"as Probate Judge; JAMES E. FLOYD, in

his official capacity as Circult

Clerk; and, LOUIE C. COLEMAN, in his

official capacity as Sheriff of

Pickens County, LEE COUNTY, qua

COUNTY, ALABAMA; HAL SMITH, in his

H

H

WN

WH

W

O

R

WN

WH

WH

FH

RK

RN

NW

WN

MW

RN

RH

R

H

F

FH

WH

WH

K

K

K

W

N

W

XK

OW

WH

WN

WN

NX

WR

WK

WK

WK

RK

XK

R

H

A

W

R

E

A

K

X

X

official capacity as Probate Judge of*

Lee County, ANNETTE H. HARDY, ln her *

official capacity as Circuit Clerk of*

Lee County, and HERMAN CHAPMAN, in

his official capacity as Sheriff of

Lee County;

Defendants.

Xx

X

%

PLAINTIFFS’ PROPOSED FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

INTRODUCTION

This matter is before the Court on the plaintiffs’

petition for preliminary injunction and class certification,

dated February 6,

defendants:

DESCRIPTION

Motion to Dismiss

Motion to Dimiss or Change Venue

Motion to Dismiss Action

Motion to Dimiss and Change Venue

Motion to Transfer, Improper Venue

Motion to Sever

Motion to Dismiss or Transfer

Motion to Dimiss

Motion to Dismiss

Motion to Dimiss & Venue

Motion to Dismiss

DATE

1/8/86

1/10/86

1/10/86

1/14/88

1/14/86

1/14/86

1/18/86

1/14/86

1/14/86

1/16/86

1/17/86

1986, and on the following motions of the

COUNTY DEFENDANTS

Etowah

Lawrence

Pickens

Etowah

Etowah

Etowah

Calhoun

Lawrence

Coffee

Talladega

Escambia

Motion to Dismiss 1/17/86 Escambia

Motion 1/24/86 Lawrence

Following oral argument on February 7, 1986, the Court

entered an order on February 10, 1986, setting all of the

aforesaid motions for evidentiary hearing on March 4, 1986. These

findings of fact and conclusions of law are based on the evidence

adduced at the March 4, 1986, evidentiary hearing.

Plaintiffs John Dillard and other named plaintiffs

residing in Crenshaw County filed this action on November 12,

1985, alleging that the at-large method of electing members of

the Crenshaw County Commission have both the purpose and effect

of diluting the voting strength of black citizens of Crenshaw

County, in violation of the amended Section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. section 1973, and the fourteenth and

fifteenth amendments. On December 13, 1985, plaintiffs moved for

leave to add seven additional counties. The Court granted the

motion to amend the complaint to add the additional counties on

December 19, 1985 of the court’s order.

Later, by motion dated February 19, 1986, plaintiffs

moved for leave to further amend their complaint to challenge the

at-large election of Lee County Commissioners, alleging that an

out-of-court agreement for Lee County voluntarily to change to

district elections had fallen through. The Court granted the

motion to add claims against Lee County on February 21, 1986.

By their petition for preliminary injunction,

Plaintiffs are seeking +0 obtaln preliminary rellef in the nature

of an order requiring single-member district elections in all

nine counties in the upcoming 1986 regular elections.

Alabama has 67 counties. The nine counties whose

at-large county commission election systems are challenged in

this action are the only ones with significant black populations

that have not been forced, elther by court order or by threat of

litigation, to change to single-member districts. Other lawsults

are pending against the at-large county commissions in Dallas,

Henry, Madison, Marengo and Houston counties.

In filing this lawsuit, plaintiffs called to the

Court's attention the intent of Congress in its passage of the

Voting Rights’ Amendments of 1982 to "deall] with continuing

voting discrimination, not step-by-step, but comprehensively and

finally." Senate Judiciary Committee Report, S.Rep. No. 97-417,

oD...

The 1982 extension of the Voting Rights Act by Congress

made clear that full enfranchisement of black citizens 1s a top

priority; delay is not acceptable. By their several motlons, the

defendants here seek to create nine separate lawsuits to be tried

against each of the counties in three different courts.

Obviously, the delays created by such severance and transfer

would result in yet another eletion in which black citizens of

Alabama are, 1f plaintiffs’ claims are true, effectively

disfranchised.

Plaintiffs base their claims against the eight counties

first and foremost on a claim of intentional discrimination on

the part of the State of Alabama, acting through its Legislature,

which plaintiffs claim has for over one hundred years

intentionally manipulated at-large election schemes for county

commissions for the specific purpose of minimizing the voting

strength of black citizens. Plaintiffs contend that there is a

racially motivated pattern and practice on the part of the state

Legislature that infects the election systems of all county

commissions in Alabama. They have advanced historical proof with

statewide scope and implications. It goes beyond the historical

"background" of official discrimination that is one of the

factors under the Section 2 "resulis" standard or under the

Yhite/Zimmer "totality of circumstances" intent standard.

The historical proof of a statewide, racially

motivated, legislative pattern and practice of statutory

enactments concerning at-large county commission election systems

is the key to plaintiffs’ entitlement to class certification, to

& preliminary injunction, to joinder of all the remaining

counties with racially dilutive at-large systems, and to the

denial of the motions to dismiss or for change of venue.

FINDINGS OF FACT

Historical Evidence of the Legiglature’'s Racial Intent

1. Plaintiffs presented evidence, primarily through the

testimony of their expert historian, Dr. Peyton McCrary,

professor of history, University of South Alabama, of a racially

discriminatory legislative intent to enact single-member distict

election schemes for county commissions only when blacks have not

been in a position to control any of the single-member districts;

otherwise, the Legislature has enacted, maintained and

strengthened at-large election systems to dilute black voting

strength. The evidence is summarized as follows:

2. In the latter part of the 19th century, following

Alabama's "redemption" by the white-supremacist Democratic party,

the Legislature passed local laws establishing gubernatorial

appointment of county commissioners in Black Belt counties

threatened with large black voting majorities, including

Montgomery, Dallas, Wilcox, Autauga, Macon, Chilton, Barbour,

Butler and Lowndes counties. A similar appointive system of

county commissioners in Florida was one of the historical facts

relied on to find intentional discrimination in McMillan v.

Escambia County, 688 F.2d 960, 967 (5th Cir. 1982), vacated on

other grounds, 104 S.Ct. 1577 (1984).

3. Standard historical works have recognized that the

purpose of gubernatorial appointments in several Southern states

during the nineteenth century had the purpose of preventing the

election of black county commissioners in those areas that

retained black voting majorities. See C. Woodward, Qrigins of

the New South, 1877-1913 54-55 (1951); E. Anderson, Race and

Politics in North Carolina. 1872-1901 568-87 (1981); H. Price, The

Negro and Southern Politics: A Chapter of Florida Higtory 13

(1957); J. Kousser, The Shaping of Southern Politics 94-95

(1974).

4. The authoritative Alabama histories specifically

identify the gubernatorial appointment of county commissioners in

eight "black belt" Alabama counties as a scheme after

Reconstruction to prevent Negro representation. M. McMillan,

Constitutional Development in Alabama, 1798-1901 222 (1955).

5. Before 1900 there was widespread use of

single-member district county commission elections, but most of

them changed to at-large schemes during the Populist period, when

whites were threatening to form coalitions with blacks. These

trends can be seen in the following table:

Counties With District Election Systems Before 1900

County

¥inston

Marengo

Morgan

Coffee

Dale

Geneva

Etowah

Cullman

Marion

Crenshaw

Covington

Pike

Chilton

Cherokee

Yashington

Blount

DeKalb

Marshall

Bullock

Lamar

Baldwin

Butler

Date(Dist)

1866

186%

1866

1867

1867

1870

1879

1879

1879

1884

1884

1884

1884

1884

1887

1887

1889

1889

1889

1891

1893

1893

Date (At-Large)

1895

1800*

%Black(1890)

0

76

14

40

36

48

Choctaw 1893 - 53

Fayette 1893 1894 13

Shelby 1893 hy 31

Pickens 1893 1894 58

6. There was a significant shift to at-large county

commission elections in the 1890's at the time of the Populist

Revolt. Those counties included :

District Systems That Shifted to At-large: 1890's

County Date of Shift Black%(1890)

Winston 1895 0

Geneva 1895 o

Etowah 1891 17

Cullman 1895 0

Covington 1894 11

Pike* 1891 37

Chilton** 1891 21

Washington 1804 41

Blount 1895 8

Bullock 1894 78

Lamar 1804 19

Baldwin 1894 36

Fayette 1804 13

Pickens 1894 58

Shifted back to districts - 1893

** Shifted back to districts - 1807

7. After 1901, following the massive disfranchisement

of black voters, there was a significant shift in the statutory

pattern toward single-member districts for county commissions,

particularly in counties that were heavily black. The following

table summarizes the changes to single-member districts in the

first quarter of the twentieth century:

Counties Shifting to Districts, 1900-1930

1

County Date of Shift

Barbour 1903

Bibb 190%

Butler 1900

Calhoun

Chambers

Choctaw

Coffee

Conecuh

Covington

Hale

3

Percent black is calculated according to the federal

dicennial census next nearest to the date of the change.

Henry

Houston

Madison

Marengo

Monroe

Montgomery

Shelby

Sumter

Talladega

8.

systems" in which single-member districts were used in the

white-only Democratic primaries, while the general elections

(which were the only elections in which the few enfranchised

blacks could vote) were held at large.

688 F.2d at 967. The following table summarizes the changes to

dual systems :

County

Autauga

DeKalb

Elmore

Cullman

Franklin

19023

19158

1901

1919

1800

1807

1915

1927

1919

There was also a substantial number of

TN

$)

]

ol

-J

—

nN

Compare with McMillan,

"dual

Counties With District Primaries and

At-Large General Elections

12 -

Lauderdale

Macon

Morgan

Pickens

Tallapoosa

Walker

Winston

*nearest decennial census

9. From approximately 1915 to 1944 the efforts of white

supremacists primarily were aimed at maintaining and defending

their complete control. In 1944, the Supreme Court struck down

the all-white Democratic party primary. Smith v. Allwright 321

U.S. 649 (1944). The reintroduction of the federal presence via

the Civil Rights Acts of 1957, 1964 and 1965 eventually removed

most of the formal legal barriers to black voting. See

generally, Blacksher and Menefee, "From Reynolds v. Sims to City

of Mobile v. Bolden: Have the White Suburbs Commandeered the

Fifteenth Amendment?," 34 Hast.L.Jd. 1, 1-2 and n.4 (1982).

10. After Smith v. Allwright, there was a decided

shift back to the use of at-large elections. The following table

displays these changes :

Counties Shifting From District to Atlanta After 1945

County Date of Shift %Black*

Barbour 1965 52

Bibb 1971 28

Butler 1969 40

Chambers 1959 37

Cherokee 1973 | 9

Chilton 1963 16

Choctaw 1965 50

Covington 1971 15

Cullman 1955 1

DeKalb 1969 2

Franklin 19863 1

Hale 1965 71

Houston 19583 29

Lawrence 1069 19

Madison 1969 15

Marengo 1955 69

Marshall 1969 Q

Montgomery 1957 30

St. Clair 1959 17

Talladega. 1951 3]

Washington 1951 39

*nearest decennial census

11. The Alabama Legislature also took steps to

foreclose even the possibility that blacks could elect candidates

Of thelr choice in at-large elections. Theoretically (if not

practically), in a true at-large election scheme, the top vote

getters were elected even if they did not achieve election

majorities. A cohesive minority group, like black voters,

theoretically could vote for only one candidate, thus avoiding

giving votes to all the other candidates and increasing the

likelihood their favored candidate could win by plurality. This

practice 1s commonly known as "single-shot voting".

12. In 1951, the Legislature passed a law to prohibit

single-shot voting in municipal elections. Act No. 606, 1951

Acts of Alabama, p. 1043. This Act was sponsored by

Representative Sam Engelhardt of Macon County, who was one of the

founders of the White Citizens Council movement in the 1950's and

was a notorious segregationist. Sam Engelhardt was the author of

the famous Tuskegee gerrymander that was struck down in Gomillion

vy. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960).

13. According to Senator Miller Bonner of Wilcox

County, who was Sam Engelhardt’s father-in-law, the

anti-single-shot bill was aimed at Macon County.

Of the 2500 registered voters, he said, 622 are colored

and most of them vote in Tuskegee.

Bonner said there are some who fear that the

colored voters might be able to elect one of their own

race to the city council by "single-shot"

voting--marking only one name on the ballot instead of

as many as there are offices to fill.

Mobile Register, August 29, 1951, p.4.

14. Anti-single-shot laws were passed to cover primary

elections, including county commission elections, in 1956 and

1957. Act No. 44, 1956, Acts of Alabama, p.337; Act No. 478, 195%

Acts of Alabama, p.661.

15. In 1961, the Legislature enacted, first for primary

elections, then for every state and county primary, general, or

municipal election in which candidates are to be nominated or

elected to two or more offices, a requirement that candidates run

for numbered places. Act No. 570, 1961, Acts of Alabama, p.670;

Act No. 221, 1981 Acts of Alabama p.2254. Act No. 231 expressly

repealed the earlier anti-single-shot law, which was no longer

necessary, because numbered posts accomplished the same result,

namely, requiring candidates favored by blacks to end up in

head-to-head contests with candidates favored by whites.

16. There is also "smoking gun" evidence of the racial

motive behind the 1961 numbered post laws. For example, at a

regularly scheduled meeting of the State Democractic Executive

Committee in Montgomery on January 20, 1962, Frank Mizell of

Montgomery said:

I would say this, that we have got a situation in

Alabama that we are becoming more painfully aware of

every passing day, that we have increasing Federal

pressure too, and a concerted desire and a campaign to

register negroes en masse, regardless of the fact that

10 i=

many of them ordinarily cannot qualify because of their

criminal records, or criminal attitudes, because of the

fact that they are illiterate and cannot understand or

pass literacy tests, but those qualifications are

things that don’t worry the people from Washington, the

army of people who are here in Montgomery County

harassing our Board of Registrars, who are harassing

the Registrars throughout most of the State of Alabama;

some counties they haven’t moved into yet, but it is

Just a matter of time before they get into all of them,

and in one county where they were few darkies

registered, there has been probably increased 4 or 5

hundred per cent already, and the thought behind this,

you understand this is not at this time a life or death

matter, and I understand that there are honest

dlfferences of opinion on it, but it has occurred to a

great many people, including the Legislature of

Alabama, that to protect the white people of Alabama,

that there should be numbered places.

Proceedings of the State Democratic Executive Committee of

Alabama, Honorable Sam Engelhardt, presiding, Montgomery,

Alabama, January 20, 1962, at p.13.

17. Further on, Mr. Mizell tied the anti-single-shot

and numbered place laws together:

Now as you all know that we have had up until

recently a law that prohibits single-shot votes, that

the law against single-shot votes has been repealed,

and consequently if you have a group of people who want

to vote as a bloc, whether they be negroes or

otherwise, of course, we do know from past experience

you can go into the negro boxes, each of the counties

where they have heavy registration, see where they vote

right down the line for this person or that person. We

know that they are easily manipulated by the connivors

and that they would be manipulated into single

shotting, and if they did, it could happen as it did up

in Huntsville.

In Huntsville they had a couple of negroes, as I

understand, that ran for the State--1 mean for the City

Council. And they eased in there with the group, and

they might near got elected, and those people at

Huntsville up there go so worried about it they came

down and got the law changed, so as far as Huntsville

is concerned, and made the City Commissioners run by

place number, so that you could spot them, and if you

have this type of thing in the primaries, so far as the

Committees are concerned, it would have the effect as a

lot of people has advanced the idea of this, in the

first place if you got a negro or scallowag [sic] who

wants to come in with the group, he just get in there,

say, "Well, I will get in there, and they can single

shot for me," and if you got three or four thousand

negro voters, you will have more than that in a

District, of course, you will have several thousand

over a Congressional District, they come in, single

shot vote for that one man, and you will begin to have

Negroes on your State Committee; because with that

single shot they can assure that one of them will get a

ma jority to start with.

Id. at 14.

18. It should be noted that Senator Archer, who

sponsored Act 221, the numbered place law for the whole state,

was from Madison County. As Frank Mizell had referred to in the

passage quoted above, the Madison County legislative delegation

had required that Huntsville city elections be conducted with

numbered posts, against the wishes of the Huntsville city

officials themselves.

19. The numbered post law is still in effect for all

elections in Alabama, and it is further evidence of the

Legislature's underlying purpose to use at-large elections to

minimize black voting strength, in many cases regardless of the

contrary wishes of local officials.

20. The numbered place requirement had been installed

in some localities for racially discriminatory reasons even

before passage of the 1961 statewide law. In 1956, Senator

18

Eddins, an ally of Sam Engelhardt and co-leader of the White

Citizens’ Council, sponsored a population bill that applied to

both Tuskegee and Demopolis, requiring the use of numbered places

in thelr municipal elections. Act No. 19, 1956 Acts of Alabama,

p.43. This numbered place law was enacted only a year after

Eddins had sponsored bills that changed the single-member

district elections of both the County Commission and School Board

in Marengo County to at large. Act No. 17, 1955 Acts of Alabana,

P-45; Act No. 184, 1955 Acts of Alabama, p.458. See United

States v. Marengo County, 731 F.24 1546, 1571 n.5 (11th Cir.

1984).

21. In 1965, there were "smoking gun" admissions by

legislators regarding the racial reasons for changing from

single-member districts to at-large elections of county

commissions in Barbour County and Choctaw County.

22. Senator James S. Clark of Barbour County sponsored

a Local Act passed in 1965 which changed the method of electing

the Barbour County Board of Revenue from single-member districts

to at large. Senator Clark’s bill was introduced against a

background of increased black voter registration and the

candidacy of Fred Gray for a legislative seat from Barbour,

Bullock and Macon counties. Senator Clark is reported as saying:

"a further consideration in introducing this bill would be to

lesson [sic] the impact of any block [sic] vote in any districts

19 -

which has a relatively small number of eligible voters." The

Clavion Record, Thursday, March 25, 1965, p.l. See Act No. 10,

1965 Acts of Alabama, p.31l.

23. It is relevant that, a year later, Judge Johnson

found judicially that a resolution adopted by the Barbour County

Democratic Executive Committee in March 1966, changing the method

of electing county committee members from a beat system to an

at-large system, was racially motivated.

Having reviewed the facts as stipulated and

outlined above, and the arguments and the parties in

thelr briefs, this Court concludes that the March 17,

1966, resolution, adopted by the Democratic Executive

Committee of Barbour County, Alabama, was born of an

effort to frustrate and discriminate against Negroes in

the exercise of their right to vote, in violation of

the Fifteenth Amendment and 42 U.S.C. section 1981.

Smith v. Paris, 257 F.Supp 901, 903-04 (M.D.Ala. 1968).

24. Act No. 4236, 1965 Alabama Acts, p.626, was sponsored by

Senator Albert H. Evans, Jr., of Choctaw County. It would have

changed the Choctaw County commission method of election from

single-member districts to at-large voting. According to the

local newspaper:

Many who support the move to change the system say

they advocate the change because of the increasing

number of Negro voters that have been qualified in

recent weeks. This, they say, would increase the

likelihood of a Negro being elected from the Second

District of Choctaw. That is the district presently

represented by Mr. C. R. Ezell. Supporters of the

proposed change have indicated that as many as 2,000

Negroes are now registered; many of them in the second

district. They maintain that by electing the

commissioners on an at-large basis the threat of an

effective Negro bloc vote will be eliminated.

The Choctaw Advocate, November 18, 1965, p.l.

25. However, in the referendum, the change to at-large

elections was defeated by the Choctaw County voters. The local

newspaper reported that many white voters opposed the change for

reasons not related to race. However, the bill's supporters were

unequivocal about their racial reasons for supporting it:

Supporters of the change voiced a concern over the

likelihood of a Negro being elected next year in the

District 2 which is currently being represented by C.

R. Bzell,

Local political observers were also quick to point

out the boxes in which the Ku Klux Klan's strength is

thought to be concentrated. Boxes in those areas voted

in favor of the change.

The Choctaw Advocate, December 2, 1965, p.l.

26. In 1971, after several federal court decisions had

ordered counties with malapportioned districts to use at-large

elections, a similar suit was filed for Choctaw County. However,

blacks intervened and thwarted the collusive attempt to get

court-ordered at-large elections. Broadhead v. Ezell , 348

F.Supp. 1244 (S.D.Ala. 1972).

27. As can be seen from the table set out on page ____ ,

supra, following enactment of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the

shift toward at-large county commission elections in Alabama

became a landslide. By 1975, only six of Alabama's 67 counties

were still using single-member district elections for county

commission: Blount (1.6% black), Lamar (12.0% black), Lauderdale

(9.7% black), Limestone (14.2% black), Marion (2.3% black) and

Shelby (10.5% black).

28. This Court has on numerous occasions noted the

pervasiveness of Alabama's history of official discrimination

against blacks with respect to voting and "in practically every

area of political, social, and economic life." Harris v.

Graddick, 592 F.Supp 128, 130 (M.D.Ala. 1984), and cases cited

therein. The use of at-large elections for the county

commissioners in particular has been struck down by federal

courts in at least 16 counties: Barbour, Chambers, Choctaw,

Clarke, Conecuh, Hale, Jefferson, Marengo (remand proceedings

still pending), Mobile, Monroe, Mongtomery, Pike, Russell

(settlement pending), Tallapoosa, and Tuscaloosa. At-large

systems have also been struck down with respect to school boards

and municipalities in Alabama, to many to list here. This court

has even rejected as racially discriminatory attempts by the

Alabama Legislature to utilize multimember districts when

reapportioning the Legislature itself. Sims v. Amos, 336 F.Supp

924, 935-36 (M.D.Ala. 1972), aff’'4.409 U.S. 942 (1972).

29. From the 1870's until 1965, the State used legal

subterfuges to prevent blacks from registering and voting. Since

1965 some counties in Alabama have used voting practices which

night have had the effect of hindering registration of, voting

by, and the election of blacks. See Plaintiffs’ Request for

Judicial Notice 1-12.

30. Until the 1970's Alabama maintained a de jure

system of segregated schools. See Plaintiffs’ Request for

Judicial Notice 13-45.

3l. Until the 1970's Alabama prohibited intermarriage

or sexual relations between persons of different races. See

Plaintiffs’ Request for Judicial Notice 51-55.

32. Until the 1960's Alabama maintained a de jure

segregation of persons using public transportation. See

Plaintiffs’ Request for Judicial Notice 56-7.

33. Throughout most of the last century, Alabama has

discriminated against blacks in its judicial system. See

Plaintiffs’ Request for Judicial Notice 58-61.

34. Until the 1970's Alabama maintained a de Jure

system of segregated institutions such as hospitals. See

Plaintiffs’ Request for Judicial Notice 62-69.

35. Subtle or overt racial appeals have been used in

political campaigns in the State within the last 20 years. See

Plaintiffs’ Request for Judicial Notice 82-93.

36. The Court finds, as a matter of fact, that from

Reconstruction to the present the Alabama Legislature has enacted

laws governing the election of county commissioners throughout

Alabama at least in party pursuant to an intentional Policy or

practice of utilizing at-large election schemes to minimize black

voting strength.

87. Pursuant to the aforesaid intentional policy or

practice of racial discrimination, the Alabama Legislature has at

various times enacted local laws changing county commission

election systems from a less racially dilutive one to an at-large

system and has enacted both local and general laws strengthening

or enhancing the dilutive power of existing at-large election

schemes for county commissions.

At-Large Election Systems

38. No black persons have ever been elected in

countywide elections in any of the counties presently before the

Court.

39. The following black candidates have run

unsuccessfully for office in Calhoun County:

name office year

Ralph Bradford county commission 1968

A.A. Scales state house 1982

40. The following black candidates have run

vasuccegsfully for office in Coffee County:

name office year

Elma Brock County Board of Ed. 1970

41. The following black candidates have run

unsuccessfully for office in Escambia County:

name Offlce year

William America Co. School Bd. 1976

Alfred Middleton County Commission 1982

42. The following black candidates have rur

unsuccessfully for office in Etowah County:

name Office year

Walker S. Alexander Co. School Bd. 1968

Leon Ballou Oo. Comm. 1976

43. The following black candidates have run

unsuccessfully for office in Lawrence Countv: Y

SR

«3% 9)

name office year

R.A. Hubbard Co. School Bd. 1972

Theodore Porter Co. Commission 1972, 1980

Charles Satchel Co. School Ed. 1976

¥illie Ed Warren Co. School B4. 1980

Moses Jones Co. Commission 1984

44. The following black candidates have run

unsuccessfully for office in Pickens County:

nane office year

James H. Corder Co. Comm, 1982, 1974

¥illie GC. Ball Sheriff 1974

Eliezer Washington Co. Comm. 1980

Mrs. Dunner Hill Co. School Bd.

Bantum Co. Bchool Bd.

Flem Grice Co. Comm. 1974

Mrs. Spiver Gordon State house 1974

45. The following black candidates have run

unsuccessfully for office in Talladega County:

nam Qffice year

Wilby Wallace Co. Commission 1982

Horace Patterson state house 1974, 1978

Arnold Garrett Co. Commission 1978

46. Associate Justice Oscar W. Adams, Jr., did not

recelve a majority of the vote in the 1982 Democratic Runoff in

any of the counties presently involved in this action, except

Calhoun.

26

47. All of the elections listed in the preceding

paragraphs, in which black persons were candidates, were

characterized by racially polarized voting.

48. The black population of the defendant counties is

displayed in the following table

Population of Counties by Race, 1980

Total Total Blk %Blk Total

County Population Population Population

Calhoun 119761 21074 17.80

Coffee 38553 6532 16.95

Escanbia 38440 11376 29.59

Etowah 103087 13809 13.40

Henry 15302 5799 37.90

Lawrence 50170 5074 16.82

Pickens 21481 8078 41.80

Talladega 73826 22745 20.81

source: Bureau of the Census. Department of Commerce. Census

of Population. Characteristics of the Population. General

Social and Economic Characteristics. Alabama. PC80-1-B. Table 15.

49. The black populations in all of the defendant

counties suffer serious socio-economic disadvantage that further

exaggerates the racially dilutive effect of the at-large election

systems. The following tables, taken from the 1980 census,

display some aspects of this disadvantage:

Median Household Income in 1979 by County and by Race

White Median Black Median* %Black

Household Income Household Income of White

County in 1979 in 1979 Incone

Calhoun $ 14836 $ 230 35.47

Coffee 15460 8014 51.84

Escambia 13644 7676 56.26

Etowah 14184 8726 61.52

Henry 13958 -

per capita 6161 2763 44.85

Lawrence 12016 -

Per capita 5147 3143 61.06

Pickens 13069 6364 458.70

Talladega 14071 8796 62.581

*Note: Black median household income data suppressed for Crenshaw,

Henry and Lawrence counties;

per capita income data substituted.

source: Bureau of the Census. Department of Commerce. 8 Of

Population. Characteristics of the Population. General Social

and Economic Characteristics.

Percent of Families with

Alabana.

1979 Income Below

Poverty Level by Race for Counties

Yhite Black

County Families Families

Calhoun 0.4 31.5

Coffee

Escambia

Etowah

Henry

persons

Lawrence

persons

Pickens

Talladega

Source:

Population.

10.9

©

C

R

10.6

Bureau of the Census.

Characteristics of the Population.

Alabama. PC80-1-C2, and Economic Characteristics.

50. The following table demonstrates

OL

C ed

41.8

46.4

393. no

Department of Commerce.

hat the

, ¢

census

General Social

Table 187.

socio-economic disadvantage of blacks in the defendant counties

1s symptomatic of the situation in the State of Alabama as a whole:

Median and Mean Income of Persons by Age Categories,

by Educational Level and by Race, Alabama, 1980 Census

18-24 vears old

with income

mean income:

395 hr/week

mean income:

40 weeks

0-7 Years

Education

White Black

4 Years

High School

White Black

$7587 3 5178

8883 6629

10449 8208

4 Years

College

White

©

~ © 9)

0,

25-34 years old

with income 7463 49060 13827 0127 16724 12593

mean income:

35 hr/wk 10040 7045 14954 10489 18587 13507

mean income: :

40 weeks 11318 7903 15614 114186 1921%Y 14830

55-64 years old

with income 7487 5702 15767 8995 25972 12688

mean income:

35 hr/wk 12636 0404 20830 129048 34467 17216

mean income:

40 weeks 13587 101186 21485 13203 35634 18397

60-64 years old

with income 6621 5076 14525 7311 24336 11250

nean income:

38 hr/vk 11860 O17 208185 12249 33187 .18585

mean income:

40 weeks 12898 0829 21458 125902 33830 19582

source: Bureau of the Census. Department of Commerce. Census of

Population. Characteristics of the Population: Detailed Population

Characteristics. Alabama.

CONCLUSIONS OF LAW

1. This Court has jurisdiction over the parties and the

subject matter of this action pursuant to 28 U.S.C. sections 1331

and 1343 and 42 U.S.C. section 1973(j)(f).

2. Pursuant to Rules 23(a) and 23(b)(2), Fed.R.Civ.P.,

the plaintiffs are due to be certified as representatives of

plaintiff class and subclasses in each county. All such persons

have been, are being, and will be adversely affected by the

respective defendants’ practices complained of in the amended

complaint. The plaintiff class constitutes an identifiable

social and political minority in the respective communities, who

have suffered and are suffering invidious discrimination. There

are common questions of law and fact affecting the rights of the

members of the class in each county who are, and continue to be,

deprived of the equal protection of the laws, the Voting Rights

Act in particular, because of the at-large schemes for electing

members of their county commissions. These persons are So

numerous that joinder of all members is impracticable. There are

questions of law and fact, common to each set of plaintiffs and

the subclass they seek to represent. The interests of the class

and each subclass are fairly and adequately represented by the

named plaintiffs from the respective counties. The respective

county defendants have acted or refused to act on grounds

generally applicable to the class, thereby making final

injunctive relief and corresponding declaratory relief with

respect to the class as a whole and with respect to the subclass

each county.

3. The plaintiffs have established a racial motive on

the part of the Alabama Legislature with respect to both general

laws and local laws affecting county commission election systems

-_ 3] -

throughout the state. Accordingly, they have established a

statewide violation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act, as

amended. It will not be necessary for plaintiffs to proceed with

proof of a county-by-county violation under the Section 2

"results" standard.

[A] violation of section 2 occurs either when official

action is taken or maintained for a racially

discriminatory purpose or when such action results in a

denial or abridgment of the right of any citizen to

vote on account of race.

Buskey v. Oliver, 565 F.Supp 1473, 1481 (M.D.Ala. 1983), citing,

Senate Judiciary Committee Report, S.Rep. No. 97-417, reprinted

in 1982 U.S. Code, Cong. & Admin. News at 205 (footnote

omitted).

4. The Arlington Heights method of proving

discrimination is applicable to a pattern or practice of conduct

as well as a discrete event. Village of Arlington Helghts v.

Metropolitan Housing Development Corporation 429 U.S. 252, 266

and n.14 (1927) (Court makes clear that either a pattern of

official action or a single act may be shown to be discriminatory

by way of its analysis); Dowdell v. City of Opopka, 698 F.2d

1181, 1182 (11th Cir. 1983) (Arlington Heights analysis used to

find unlawful defendants’ pattern of providing municipal

services); dean v. Nelson, 711 F.2d 1455, 1490 (11th Cir.

1983) (Arlington Heights analysis used to determine existence of

— pb

‘ongoing pattern of discrimination" against Haitian immigrants);

Lodge v. Buxton, 639 F.2d 1358, 1367-68 (5th Cir. 1981) (voting

rights); United States v. Georgia Power Company, 634 F.2d 929,

937 (5th Cir. 1981)(employment discrimination); United States v.

Texas Education Agency, 564 F.2d 162, 166 (5th Cir. 1977),

rehearing denied, 579 F.2d 910, 914 (1977) (Arlington Heights

analysis used to find that defendant school district had adopted

various segregative policies with respect to Mexican-Americans);

Kirksey v. Board of Supervisors of Hinds County, 554 F.2d 139,

147-48 (5thCior. 1977) (voting rights; Arlington Heights analysis

applied to defendants’ actions overtime to determine

discriminatory purpose).

5. In the instant case, Plaintiffs have proved a

racially discriminatory statewide legislative pattern and

practice based on direct, historical evidence, rather than by

relying on the "circumstantial factors" found in White v.

Regester, 412 U.S. 755 (1973), and Zimmer v. McKeithen, 485 F.24

Fast Carroll Parish School BA, v. Marshall, 424 U.S. 638 (1976).

Compare Buskey, 565 F.Supp at 1473, (finding Section 2 violation

based on direct evidence of racial intent) with Harris v.

Graddick, 593 F.Supp 128 (M.D.Ala. 1984)(finding Section 2

violation based on discriminatory result).

6. By thelr proof of historical legislative intent,

plaintiffs have established a prima facie entitlement to relief

under the Voting Rights Act. The burden is on the defendants to

demonstrate that the racially motivated at-large election schemes

in their respective counties no longer disadvantage black

Citizens. See Sims v. Amos, 365 F.Supp 215, 220 n.2 (M.D.Ala.

1973) (3-judge court), aff'd sub nom. Wallace v. Sims, 415 U.S.

902 (1974), citing Keves v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189

(1973). At most, Plaintiffs need establish only that racially

polarized voting has consistently defeated black candidates in

the defendant counties to obtain relief after historical intent

has been proved. NAACP v. Gadsden County School Bd., 691 F.24

078, 982 (11th Cir. 1982), citing McMillan v. Escambia County,

638 F.2d 1239, 1248 n.18 (Bth Cir. 1981). Thus, it will not be

necessary for Plaintiffs to try individual "totality of the

circumstances" "results" cases against the eight counties.

II. REQUEST FOR PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

In order for a preliminary injunction to issue, a

district court must be satisfied that a plaintiff has

clearly met all of the following four prerequisites:

(1) that there is a substantial likelihood of success

on the merits; (2) that without the relief there will

be irreparable injury; (3) that the threatened harm to

the plaintiff outweighs any threatened harm to the

defendants; and (4) that the public interest will not

be disserved by granting the injunctive relief.

Harris, 523 F.Supp at 132, ¢ilting Shatel Corp. v. Mao Ta Lumber

¥ Yacht Corp., 687 F.2d 1352, 1354-55 (llth Cir. 1983).

Plaintiffs in the instant case have met all four prerequisites.

7. As demonstrated in the sgotegoing findings of fact

and conclusions of law regarding the discriminatory intent of the

Alabama Legislature and the continuing effect of at-large

election systems in the defendant counties, plaintiffs have

established a substantial likelihood of success on the merits.

8.

since the plaintiffs seek preliminary

injunctive relief pursuant to section 2 of the Voting

Rights Act of 1965, as amended, they should not be and

are not required to make the usual showing of

irreparable injury as a prerequisite to relief; rather,

such injury is presumed by law. ... Moreover, section

2 and its history reflect a strong national mandate for

the immediate removal of impediments, intended or not,

to equal participation in the election process. Thug,

when section 2 is violated, the public as a whole

suffers irreparable injury.

bt J Harris v. Graddick, supra, B93 F.Supp at 135.

9. In any event, as a practical matter, Plaintiffs and

the class they seek to represent will suffer irreparable injury

1f preliminary relief is not granted. @ualifying for the

Democratic Party primary begins March 1 and ends April 3, 1986,

for primary eletions scheduled for June 3, 18986, with a runoff on

June 24, 1986. Unless the preliminary injunction is granted, the

1986 primary and general elections for county commission in the

defendant counties are likely to be held at large, and the voting

- 35

strength of black citizens once again will be submerged or

minimized.

10. The defendants wlll not suffer irreparable injury

1f the preliminary injunction is granted. All incumbent

commissioners will be able to stand for election if the court

orders they be held from single-member districts. If the court

subsequently rules that the at-large election schemes do not

violate the amended section 2, at-large elections can be restored

without any irreparable injury to elected officials or the

citizens of the respective counties.

ll. As noted earlier, the public interest is expressed

by the congressional policy underlying the amended Voting Rights

Act. That policy emphasizes the immediacy of the need for relief

from racially dilutive election systems. Qnly preliminary relief

can fully serve this policy and the public interest. See Harris,

593 F.Supp at 136.

12. Accordingly, the Court concludes that plaintiffs

have established their entitlement to a preliminary injunction.

VENUE

13. As the Lawrence County defendants essentially

concede (Lawrence County Defendants’ Brief at p.3), if joinder of

the plaintiffs and defendants in this lawsuit is proper, venue in

the Middle District of Alabama is proper under 28 U.S.C. sec.

1392(b). That statute provides that in a suit with multiple

defendants residing in different districts, venue is proper in

any of the districts in which any of the defendants resides.

Daniels v. Murphy, 528 F.Supp 2 (E.D.Okla. 1978). See United

States v. Mississippi, 380 U.S. 128, 143 (1965) (in suit

challenging registration practices in six counties, Court found

venue to be proper under sec. 1392(a) once joinder of all county

defendants held to be appropriate); Gilmore v. James, 274

F.Supp. 75 (N.D.Texas 1967); aff'd 389 U.S. 572 (1968): Brumfield

Y. Dodd, 405 F.Supp 338 (E.D.La. 1975)(3 judge court).

14. In addition, venue properly lies in the Middle

District of Alabama under 28 U.S.C. section 1391(b), because it

is the district "in which the claim arose". Plaintiffs’ central

claim is against the State of Alabama acting through its

Legislature, which sits in Montgomery, Alabama. The state is

present in this action through its subdivisions, the defendant

counties which still utilize racially dilutive at-large elections

for county commission. The traditional "divide-and-conquer"

strategy of white supremacy in Alabama fails when an

intentionally discriminatory pattern on the part of the central

government is proved.

JOINDER

15. The Defendants are mistaken in suggesting that this

case must consist of eight unrelated mini-trials presenting proof

for each county of the Section 2 (or Zimmer or Marengo County)

"results" factors. Plaintiffs have proceeded on a quite

different course. Plaintiffs’ case ln chief is based primarily

on historical evidence of a statewide scope focusing on the

actions of the Alabama Legislature. Since plaintiffs have

succeeded with this statewlde, historical intent claim, it will

be unnecessary for them to meet the burdensome and time-consuming

requirements of section 2's results test. In fact, it would be

wasteful of judicial resources and directly contrary to the

policy of the Voting Rights Act to require them to try the same

case and seek the same relief in eight separate trials in three

different courts. The issue of historical intent is precisely

the kind of common question of law and fact contemplated by Rule

20(a), Fed .R.Civ.P., as warranting joinder of parties plaintiff

and defendant in a single action.

16. Under the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure,

"Joinder of claims, parties and remedies is strongly

encouraged." United Mine Vorkers of America v. Gibbs, 383 U.S.

715, 724 (1966). Joinder of plaintiffs and defendants is proper

under Rule 20(a) Fed.R.Civ.P. where there is asserted a right to

relief "jointly, severally or in the alternative in respect of or

arising out of the same transaction, occurrence, or geries of

transactions or occurrences and if any question of law or fact

- 28

common to all these persons will arise in the action." (Emphasis

supplied). There need not be a total congruence of interests.

"A plaintiff or defendant need not be interested in obtaining or

‘defending against all the relief demanded." Rule 20(a),

Fed .R.Civ.P. The joinder provisions, including the definitions of

commonality and relatedness of transactions or occurrences, are

to be liberally construed. League to Save Lake Tahoe v. Tahoe

Redional Planning Agency, 558 F.2d 914, 91% (9th Cir. 1977):

Kolosky v. Anchor Hocking Corp., 585 F.Supp 746, 748 (W.D.Pa.

1983); Kedra v. City of Philadelphia, 454 F.Supp. 652 (E.D.Pa.

1978). Joinder is appropriate if "the operative facts are related

even if the same transaction is not involved." (Civil Aeronautics

Bd. ¥v. Carefree Travel. Inc., 513 FP.2d4 375 (3nd Cir. 1075)

(different travel agencies and individuals providing affinity

charters sued by C.A.B.; severance denied).

17. The paradigm for this statewide action is United

states v. Misgigsippi, 380 U.S. 128 (1965), where registrars in

six counties were sued for engaging in "acts and practices

hampering and destroying the rights of Negro citizens to vote, in

violation of 42 U.S.C. section 1971(a), and the Fourteenth and

Fifteenth Amendments and Article I of the United States

Constitution." Id. at 130. Five of the registrars sought

severance, four of whom also sought transfer since they did not

reside in the district or division in which suit was brought. In

determining whether joinder was proper, the Supreme Court traced

the history of acts in Mississippi from 1890 to 1962 which

prevented or restricted voting by black citizens. The Court

found joinder to be proper because the actions of each of the

registrars were but the latest in a series of transactions or

occurrences designed to disenfranchise Mississippi’s black

citizens. The Supreme Court reversed the district court, which

had denied joinder on the ground "that the complaint improperly

attempted to hold the six county registrars jointly liable for

what amounted to nothing more than individual torts committed by

them separeately with reference to separate applicants." Id. at

142. The Supreme Court rejected the district court's reasoning,

finding it sufficient that the plaintiffs alleged that "the

registrars had acted and were continuing to act as part of a

statewide system designed to enforce the registration laws in a

way that would inevitably deprive black people of the right to

vote solely beacause of their color.” Id. Plaintiffs here

challenge the remnants of the same kind of statewide system of

disenfrancisement, only by the method of election as opposed to

registration.

18. Similarly, in a number of cases outside the voting

rights context, courts have found joinder of multi-county or even

statewide plaintiffs and defendants to be appropriate in

situations where there is some common thread to the actions of

ne 40 ore

the defendants -- even 1f they acted seemingly independently -—-

particularly where the defendants acted in violation of

Plaintiffs’ federal constitutional rights. fee, e.2.. Mogslev v.

General Motors Corp., 497 F.2d 1330 (8th Cir. 1974) (severance

sought by company and union denied; same general policy of

discrimination by both suffices for joinder purposes, identity of

all events unnecessary); Coffin v. South Carolina Dept. of

Social Services, 562 F.Supp 579 (D.S.C. 1983)(age discrimination

sult against 14 defendants; defendants claimed that their actions

vere not the resuli of the same series of transactions or

occurrences, because they were independent and based on different

policies; severance denied); United States v. Yonkers Board of

Education, 518 F.Supp. 191 (S.D.N.Y. 1981)(complaint against

school board, city and Community Development agency under Titles

Iv, VI, and VIII, D.O.E. regulations, the fourteenth amendment

and contract; motion to sever denied despite variety of claims

and differences in actions by different entities which were

challenged); School District of Kansas City, Missouri v. State

of Missouri, 460 F.Supp. 421 (W.D.Mo. 1978), appeal dismissed,

(inner-city school board and school children seeking

inter-district school desegregation sued suburban school

districts, state, H.U.D., H.E.W.; defendants’ motion for

severance denied despite fact that actions of defendants were

otherwise independent and involved such different subject matter

as teacher hiring, housing, highway construction, urban renewal);

Redra v. City of Philadelphia, 454 F.Supp. 852 (E.D.Pa.

1978) (multiple plaintiffs sued city and officials for series of

events over a period of more than one year involving separate

incidents of beating and other harassment; defendants motions to

sever denied despite fact of separate incidents and independent

involvement of different defendants); Swift v. Toia, 450 F.Supp.

98% (S.D.N.Y. 1978), aff'd. 508 P.2d 313 (2nd Cir. 1979) (suit

challenging prorating of AFDC benefits; intervention granted to

plaintiffs also challenging proration, although facts of their

claims differed; joinder of commissioners in coiunties serving

intervenors allowed); Brumfield v. Dodd, 405 F.Supp. 338 (E.D.

La. 1975) (3 judge court)(plaintiffs in six parishes challenged

statewide application of state statutes by which all-white

private schools opened to defeat public school integration

received state financing; joinder held appropriate despite

different facts in each parish re: integration, use of funds,

etc. ).

19. In an analogous group of cases, plaintiffs used the

device of a defendant class action to unite claims against

multiple defendants in a single lawsuit. In those cases, as

here, the courts had to determine whether common issues of law or

1 fact were involved. In Harris v. GCraddick, 593 F.Supp 128

(M.D.Ala. 1984), this court certified both plaintiff and

42 . 2

defendant classes in a statewide suit challenging the failure to

appoint black voting officials. There, as here, defendants

protested that different circumstances in different counties

outweighed any common issues. The court rejected those

objections. §See also, Rakes v. Coleman, 318 Supp. 181

(E.D.Va. 1970), (defendant class of state court judges certified

in a suit by alcoholics against the practice of confining

alcoholics to penal and other inappropriate institutions under

state statutes allowing for the confinement for "treatment" of

alcoholics; class certified despite variations in procedures used

by the judges, in their rationalizations for the commitments, or

in the institutions to which class members were committed);

Marcera v. Chinlund, 595 F.2d 1251 (24 Cir. 1979) vacated on

TT other grounds, sub nom., Lombard v. Marcera, 442 U.S. 915 (1979)

(defendant class of 43 sheriffs certified in suit by pre-trial

detainees for contact visits in 43 separate county jails;

differences in jail construction, staffing and inmate population

insufficient to defeat certification).

<0. Finally, with respect to joinder, it is noteworthy

that the Lawrence County defendants relied in their brief on the

Lee v. Macon precedent. Here, as in Lee v. Macon, the "wide

range of activities" by central state government requires joinder

of all the county defendants in order effectively to achieve

enforcement of the Voting Rights Act. See Lee v. Macon, Order of

- 45 ~

March 31, 1970, at 3. (Order attached to defendant Lawrence

County's brief).

TRANSFER

21. Defendants have taken the position that even if

they have not been misjoined and venue in this court is Proper,

the court should nonetheless use its discretionary powers under

28 U.S.C. section 1404(a) to sever the claims against them and

transfer those claims to other federal district courts in

Alabama. Section 1404(a) authorizes transfers to another district

in which the action could originally have been brought if such a

transfer would be "for the convenience of parties and witnesses"

and "in the interest of justice." The standards governing |

transfers under section 1404(a) place a heavy burden on the

moving defendant to prove that "the balancing of interests weighs

in favor of transfer and unless this is clearly established, the

plaintiff's choice of forum will stand." H.H. Robertson Co. v.

Lumbermen’s Mutual Casualty Co., 94 F.R.D. 578, 581-2 (W.D.Pa.

1082), aff’'d 696 F.2d 982 (3rd Cir. 1982).

22. In evaluating the balance of interests, the

plaintiff's choice of forum is to be given "considerable

weight." Texas Eastern Transmission v.Marine Office Appleton and

Cox Corp., 579 F.24 881, 8687 (10th Cir. 1978). "Unless the

balance is strongly in favor of the defendant, the plaintiff's

Tn 4 4 oly

choice of forum should rarely be disturbed." Collins v.

Straight. Inc., 748 F.2d 916, 921 (4th Cir. 1984) guoting, Gulf

Qil v. Gilbert, 330 U.S. 501 (1946). Thus, courts have refused

transfers requested by defendants even where a majority of the

witnesses did not reside in the district where the case was to be

tried, gee, e.¢g., Texas Eastern Transmission v. Marine Office

Appleton and Cox Corp., supra, and where the cause of action

arose in another district, see, e.g. Collings v. Straignt, Inc.,

supra.

<5. The interests of justice in this case weigh heavily

against transfer to other districts. Transfer would involve

delays that would prevent the granting of relief in time for the

1986 elections. It would substantially increase the burden on

plaintiffs -- the aggrieved parties -- both in terms of time and

expense, requiring, for example, many additional hours in travel

time and in-court time for expert witnesses crucial to the

prosecution of voting rights claims, who would be required to

appear in three different forums for eight different trials

rather than appearing in one forum once. Since "[tlhe interest

of justice favors retention of jurisdiction in the forum chosen

by an aggrieved party where, as here, Congress has given him a

choice," Newsweek, Inc. v. United States Postal Service, 652

F.2d 239, 243 (2nd Cir. 1981), the Court should deny defendants’

motions to transfer.

Class Action Issues

24. It is axiomatic that Article III empowers federal

courts to hear only cases and controversies. One aspect of this

doctrine, standing, demands there be a direct connection between

the injuries suffered and the violations alleged. Church of

cientology v. City of Clearwater, 777 F.2d 598, 608 (11th Cir.

1985). Defendants here concede that each named representative has

standing to challenge the at-large system in his or her county.

They assert, however, that every named plaintiff must have

standing in relation to every named defendant.

25. While defendants’ argument might have merit in

commercial litigation where a single named plaintiff seeks to sue

multiple, unrelated defendants, See, Lamar v. H & B Novelty and

Loan Co., 489 F.2d 461 (9th Cir. 1973)(named plaintiff sued

several pawnbrokers with whom he had no dealings), it is

meritless in the context of this litigation. Here, plaintiffs

seek to represent black citizens who have been injured by acts

adopted by the Alabama Legislature and implemented by the named

defendants, subordinate governmental units. The crux of

plaintiffs’ case is a common historical intent to discriminate.

26. In civil rights cases such as this one, the inquiry

is "whether the class as a whole has standing to sue the named

defendants, rather than upon the narrow question of whether each

named plaintiff meets the traditional standing requirements

against each named defendant." ¥Yilder v. Bernstein, 499 F.Supp

980, 994 (S.D.N.Y. 1980). There, a plaintiff class of children

alleged that New York's statutory child placement scheme was

unconstitutional. The court, recognizing that standing is a

broader concept in civil rights cases, held the children had

at 993. See also ¥ashington v. Lee, 263 F.Supp 327 (M.D.Ala.

1968) aff'd, 300 U.8. 333 (1968) (class of plaintiffs had Standing

to challenge segregated detention facilities in Alabama, despite

the fact that not all plaintiffs had been detained in all

facilities); Q’Shea v. Littleton, 414 U.S. 491, 404 (standing

denied where none of the named plaintiff's stated a case or

controversy).

27. Even if this court accepts defendants’ stringent

standing analysis, any perceived standing problem can be cured by

certifying appropriate subclasses. This is precisely the action

taken in Young v. Pierce, 554 F.Supp 1010 (E.D.Tx. 1982). There

the court certified a class of residents and applicants in a 36

county area who had suffered discrimination in public housing.

Id. at 1026. See also Vulcan Society v. Fire Department of City

Qf White Plains. 82 F.R.D. 370 (5.0.0.7. 1975) (employment

discrimination suit by firefighters in four municipalities where

common issue was test used by all four cities; court created four

—— 417.

subclasses, one for each municipality.)

28. Resolving the standing problem does not

automatically establish that the representative plaintiffs are

entitled to litigate the interests of the class they seek to

represent. Instead, the emphasis shifts from justicibility to an

examination of the criteria of rule 23(a). Sosna v. Iowa, 419

U.S. 393, 402-03 (1975).

29. The Court finds that this cause satisfies rule

23(a) and rule 23(b)(2).

Numerosity. Whether the numerosity requirement is met

depends upon the circumstances of the case rather than upon any

arbitrary limit. General Telephone Co. v. EEOC, 446 U.S. 318,

330 (1980). The putative class in this action meets this

requirement. The number of known, identifiable class members is

at least 64,515 (less the number of black persons in the two

counties that have settled). That number, set forth in

plaintiff's motion to certify, represents the number of black

citizens in the defendant counties according to the 1980 census.

The impossibility of joining all of these class members in any

one action is obvious. When class size reaches these

proportions, the joinder/impracticability test is satisfied by

WA numbers alone. 1 Newberg on Class Actions, section 3.05, p.142

(24 E4.).

30. Commonality. Plaintiffs seek to represent a class

” 48

of persons situated precisely as themselves with regard to

defendants’ election system. There is one determinative common

question in this case: whether the State of Alabama has adopted

and maintained racially discriminatory, vote diluting, at-large

election systems for the specific purpose of denying and

abridging black citizens voting rights.

This issue 1s plain, narrow and manageable, and affects

the putative class members and the named plaintiffs alike. Thus,

the class device will save the "resources of both the courts and

the parties by permitting an issue potentially affecting every

[class member] to be litigated in an economic fashion under rule

23." General Telephone v. Falcon, 457 U.S. 147 (1982).

61. Typicality. Though closely related, commonality

and typicality are actually separate inquiries. The commonality

requirement focuses on the absent or represented class, while the

typicality requirement addresses the desired qualifications of

the representatives. "[A] strong similarity of legal theories

will satisfy the typicality requirement despite substantial

factual differences." Appleyard v. Wallace, 754 F.2d 955, 958

(11th Cir. 1088).

Here, the predominate question is whether the State of

Alabama adopted the at-large election scheme in these counties

for the purpose of discriminating against black citizens.

32. Adequacy of Representation. Whether the named

plaintiffs will adequately represent the class is a question of

fact to be raised and resolved in the trial court in the usual

manner, including, if necessary, an evidentiary hearing on the

matter. Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, 417 F.2d 1122,

1124-25 (5th Cir. 1972). The standard to be applied in this

determination is whether the named plaintiffs have qualified and

experienced counsel able to conduct the proposed litigation and

whether there is any possibility that the named plaintiff is

involved in a collusive suit or has interests actually

antagonistic to those of the remainder of the class. Id.

Plaintiffs here are represented by experienced counsel,

and there is no evidence that plaintiffs’ suit is collusive or

that plaintiffs have any interests which are actually

antagonistic to those of the remainder of the class.

33. Injunctive relief is appropriate. Defendants

have acted or refused to act on grounds which are generally

applicable to the entire class, thereby making appropriate final

injunctive and declaratory relief. This court determines that

this cause should proceed as a class action and certifies this

suggested class of plaintiffs under rule 23(b)(2) of the Federal

Rules of Civil Procedure.

PRIOR COURT ORDERS

rejected the change. Following the pattern described with

respect to Choctaw County in the findings of fact, a change to

at-large elections was finally effected for the Talladega County

Commission by means of the Brown v. Gallion lawsuit, in which

blacks did not participate.

36. There is some question whether the 1970

court-ordered change to at-large elections for Talladega County

is enforceable in light of the subsequent decision of the supreme

Court in McDaniel v. Sanchez, 101 S.Ct. 2224 (1981), which held

that redistricting plans entered by consent of the local

government still must be precleared under Section 5 of the voting

Rights Act. There have been at least two three-judge court

decisions in Alabama restoring single-member district elections

to counties that were using similar court-ordered at-large

schemes. Marshall v. Monroe County, Civil Action No. 77-224-C

(S.D.Ala., June 22, 1983); Holley v. _ Sharpe, F.Supp.

(M.D.Ala., Sept. 9, 1982) (Tallapoosa County).

37. However, plaintiffs have established their

entitlement to relief in this action under Section 2 of the

voting Rights Act, because Talladega County has failed to bear

its burden of showing that it should be allowed to continue using

at-large elections in the face of the statewide, racially

motivated pattern and practice. Requiring plaintiffs to seek the

convening of a three-judge court necessarily would be time

consuming and would increase the unlikelihood that they could

obtain relief in time for the 1986 elections.

38. Accordingly, the Court is of the opinion that the

preliminary injunction should be issued against Talladega County.

The 1970 court order in Brown v. Gallion on its face

contemplated that it would operate as a temporary plan pending

expected action by state and local authorities to provide a

constitutional redistricting plan. Although the order recited

that the court was retaining jurisdiction until such a

legislative plan was enacted, the Legislature (not surprisingly,

in light of the findings this Court has made) has failed to take

any action, and the docket records in the Northern District of

Alabama indicate the action has been dismissed. In any event,

the action in no way involve the plaintiffs in this case, and

provides no bar to their assertion of Section 2 claims in an

2

independent action.

Pickens County

39. Pickens County has a different and more substantial

2

Copies of the court orders in Brown v. Gallion and

Marshall v. Monroe County are being provided to the Court along

with these proposed findings of fact and conclusions of law.

Copies will be provided to counsel for other parties upon

request.

Claim based on a prior action. It contends that Plaintiffs’

claims in the instant case are barred by the final judgment

entered in Corder v. Kirksey, Civil Action No. 73-M-1086

(N.D.Ala., Sept. 24, 1980). Pickens County's argument is without

merit. Corder v. Kirksey was decided solely on the basis of an

asserted constitutional cause of action; it does not bar the

instant action based on the Voting Rights Amendments of 1982.

40. Here is the chronology of Corder v. Kirksey:

March 12, 1976: Judge McFadden entered a one and

one-half page order approving the Legislature's reapportionment

of the Pickens County commission residency subdistricts utilized

with the at-large election system. Final judgment was entered on

August 18, 19786.

November 1978: The Fifth Circuit vacated the judgment

and remanded the case to the district court for explicit findings

of fact using the Zimmer standards. 585 F.2d 708.

February 16, 1979: The district court entered an

order upholding the at-large system for county commission general

elections (districts are used only in the primary elections)

under Zimmer. No evidence was presented by the plaintiffs that

would allow the district courts to determine the distribution of

the black population among the districts, no evidence was

presented that would allow the court to draw inferences that the

election scheme diluted the voting strength of blacks or was

designed to discriminate against blacks, and no evidence was

presented regarding the general law of Alabama, which provides

for at-large elections for county commissions not otherwise

governed by local acts. Slip Op. at 3.

August 21, 1980: The Fifth Circuit again vacated and

remanded, this time for findings consistent with the supreme

Court's intervening decision in City of Mobile v. Bolden, which

called for findings on the issue of purpose or intent. Corder

v. Kirksey, 625 F.2d at 520.

September 24, 1980: The district court again found

that "there is no evidence that the election scheme was designed

to discriminate against blacks." Corder v. Kirksey, No.

73-M-1086, unpublished order at 3. The plaintiffs declined the

court's invitation to present further evidence. at 1,

March 16, 1981: The Fifth Circuit affirmed the

district court's holding that the at-large county commission

election scheme was constitutional, on the ground that the

district court had found "simply no facts in the record probative

of racially discriminatory intent on the part of those Officially

responsible for the Pickens County Board of Commissioners

at-large election scheme." Corder v. Kirksey, 639 F.2d 1191,

1195. The analysis of the Fifth Circuit and the district court

focused entirely on the inadequacy of the plaintiffs’

¥hite/Zimmer evidence to establish an inference of discriminatory

intent.

October 12, 1982: The Fifth Circuit denied

plaintiffs’ petition for rehearing and rehearing en banc,

concluding that the Supreme Court's decision in Rogers v. Lodge,

102 S.Ct. 3272 (1982), "does not affect our analysis or

disposition of this case." Corder v. Kirksey, 688 F.2d 991,

002.

41. Rirkgey v. City of Jdackgon, 714 F.2d 42 (8th Cir.

1983), accord, United States v. Marengo County Commigsion, 731